Fast food babies bbc

Sri Lanka: 'I can’t afford milk for my babies'

Published

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Sri Lanka is facing its worst food and fuel shortages in living memory

By Rajini Vaidyanathan

BBC News, Colombo

The smell hits you first - freshly cooked rice, lentils and spinach, served in ladles from steaming pots.

Dozens of families - including mothers with babies - are lined up with plates to get a serving of what will likely be their only meal for the day.

"We are here because we are hungry," says Chandrika Manel, a mother of four.

As she kneads a ball of rice with her hands, mixing it with the lentils and spinach before feeding it to one of her children, she explains that even buying bread is a struggle.

"There are times I [give them] milk and rice, but we don't cook any vegetables. They're too expensive."

Depleted foreign reserves and soaring inflation have devastated Sri Lanka's economy in recent months. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa - who pushed through tax cuts that shrunk the state's coffers and borrowed heavily from China to fund ambitious infrastructure projects - has been blamed for the crisis. The pandemic, which hit tourism, and the war in Ukraine, which sent oil prices rocketing, has only made the situation worse.

But now Sri Lanka is on the brink of a humanitarian crisis, the United Nations Children's Fund (Unicef) has told the BBC.

The organisation found that 70% of the country's families have cut down on food since the start of the year, and stocks of fuel and essential medicines are also fast running out.

'My children are miserable'

This is Ms Manel's first visit to a community kitchen as she found her options disappearing: "The cost of living is so high, we are taking loans to survive."

The kitchen is a month old - Pastor Moses Akash started it in a church hall in Colombo after meeting a single mother who lived off a jackfruit for three days.

Sahna and her three children are among hundreds who visit the community kitchen

"We get people who haven't had a second plate of rice for the last four months," Pastor Moses says.

By his estimate, the number of people queuing up for food has grown from 50 to well over 250 a day. It's not surprising given that food prices in Sri Lanka went up by 80% in June alone.

"I see a lot of children especially, most of them are malnourished," he says.

- 'Living in my car for two days to buy fuel'

- What's behind Sri Lanka's petrol shortage?

- No medicine for kids in a collapsing health system

Sahna, a pregnant 34-year-old who goes by her first name only, is also in the queue with her three young children. She is due in September and anxious about the future.

"My children are miserable. They're suffering in every possible way. I can't even afford a packet of biscuits or milk for my babies."

Sahna's husband, who is a labourer, earns just $10 (£8. 20) a week to support the entire family.

20) a week to support the entire family.

"Our leaders are living better lives. If their children are living happily, why can't my children?" she asks.

A looming humanitarian crisis

By the time Sahna's child is born, things are expected to get worse.

The mayor of Colombo recently said that the capital has enough food only until September.

With shortages of fuel and cooking gas, and daily power cuts, families are unable to travel to buy fresh food or prepare hot meals.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Dwindling fuel stocks have led to vast queues at pumps

"Families can't buy what they used to buy. They are cutting down on meals, they are cutting down on nutritious food. So we are definitely getting into a situation where malnutrition is a major concern," said Christian Skoog, Unicef's representative in Sri Lanka.

"We're trying to avoid a humanitarian crisis. We're not yet at children dying, which is good, but we need to get the support very urgently to avoid that. "

"

Unicef has appealed for urgent financial aid to treat thousands of children with acute malnutrition, and to support a million others with primary healthcare.

Acute malnutrition rates could rise from 13% to 20%, with the number of severely malnourished children - currently 35,000 - doubling, says Dr Renuka Jayatissa, president of the Sri Lanka Medical Nutrition Association.

The crisis has brought forth a sense of solidarity, with people often relying on the kindness of strangers. But even kindness and hope are becoming precious commodities.

Dr Saman Kumara at Colombo's Castle Street hospital says that if not for the goodwill of donors, his patients - tiny newborns - would have been at great risk.

He says his hospital is now "completely dependent on donations" for essential medicines and equipment, and urged more donors to come forward as patients' lives are in danger.

Image caption,Dr Saman Kumara says his hospital is relying entirely on donations to keep running

Back at the community kitchen, Chandrika is scooping the last morsel of food into her son's mouth.

"My best days are done. But our children have so much ahead of them," she says.

"I don't know what will happen as they grow up."

You may also be interested in:

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Media caption,Watch: Sri Lanka protests unify a nation where ethnic fault lines run deep

- Asia

- Inflation

- Sri Lanka

What Are We Feeding Our Kids? review – junk food exposé will leave you queasy | Television

Maybe we will come to measure out the pandemic in Tulleken time. The identical twin brothers – and practising doctors – Chris and Alexander (Xand) van Tulleken have had a busy year; they have rarely been off our screens for long. Respectively, they are a virologist at University College hospital, London, and an experienced public health doctor with years of experience on the frontline of disaster zones. The pair would doubtless have been commissioned to educate us on Covid – even if Xand hadn’t caught the virus and brought a personal view to the gig (Surviving the Virus: My Brother and Me). Their series Operation Ouch, and other online contributions, helped parents desperately trying to home school, in between fending off unemployment, sourcing supermarket deliveries and caring for shielding parents.

The pair would doubtless have been commissioned to educate us on Covid – even if Xand hadn’t caught the virus and brought a personal view to the gig (Surviving the Virus: My Brother and Me). Their series Operation Ouch, and other online contributions, helped parents desperately trying to home school, in between fending off unemployment, sourcing supermarket deliveries and caring for shielding parents.

Alone or together, the Van Tullekens are very good at what they do. They turn potentially dark, heavy subjects – primarily, but not always, medical – into lighter, brighter fare, still informed by their in-depth knowledge, but delivered without ego and accessible to a mass audience. In What Are We Feeding Our Kids? (BBC One), we have Chris as a solo act, looking into the health effects – particularly for children – of our increasing consumption of ultra-processed food.

The statistics are as unwholesome as a microwaved lasagna: childhood obesity has increased tenfold globally over the past 50 years, while 21% of UK children are obese by the time they leave primary school. It costs twice as much to get 100 calories from fresh fruit, vegetables and fish in the UK as it does to get them from readymade food. In 1980, our food spending on scratch ingredients versus convenience food was split 58% to 26%. It is now virtually reversed.

It costs twice as much to get 100 calories from fresh fruit, vegetables and fish in the UK as it does to get them from readymade food. In 1980, our food spending on scratch ingredients versus convenience food was split 58% to 26%. It is now virtually reversed.

Van Tulleken takes us through the science parts with his customary cheery aplomb and some help from various experts, notably Rachel Batterham, a professor of obesity, diabetes and endocrinology at University College London. The specialists explain the hormonal signals that tell us when we feel full, the brain mechanisms involved in eating and, crucially, how little research has been done into the effects of the very new, profoundly different kinds of food we have started putting into our bodies over the past few decades.

The good doctor goes on a four-week diet that matches that of 20% of the population, containing 80% ultra-processed food. Lyra, one of his children (who, sadly, is not a twin, but how brilliant would that be? I think we have earned it after the year we have had), looks on enviously as dad wires into the junk. Van Tulleken’s eyes glaze over with happiness, even as he reads up on the endless research by industrialised-food companies and the precision engineering behind “hyperpalatability”, “mouthfeel” and “bliss points”. Unable to stop eating the deliciousness even when he wants to, he begins to realise that we are all essentially self-feeding foie gras geese at the mercy of big salt/sugar/fat comestible blends.

Van Tulleken’s eyes glaze over with happiness, even as he reads up on the endless research by industrialised-food companies and the precision engineering behind “hyperpalatability”, “mouthfeel” and “bliss points”. Unable to stop eating the deliciousness even when he wants to, he begins to realise that we are all essentially self-feeding foie gras geese at the mercy of big salt/sugar/fat comestible blends.

In essence, it is hard to overeat natural foods for long. With processed stuff, you can do it within six chicken nuggets. Its ability to bypass the gut/brain messaging service is remarkable and still fundamentally unexplained. The brain changes revealed by Van Tulleken’s post-diet MRI – lit up like an addict’s – are significant enough to be published and may yet secure Prof Batterham funding to investigate further.

Little of this, perhaps, will come as news to – if I dare posit such a figure – the average Guardian reader, who tends to be interested in this sort of thing. But – again, if I dare say so – most people aren’t Guardian readers, aren’t interested in this sort of thing and, beyond a vague understanding that, in an ideal world, we would all be eating salad for main and apples for pudding, tend to assume that food is basically food and nothing sold openly on supermarket shelves can be that bad for you. It is these viewers who are Van Tulleken’s intended audience.

It is these viewers who are Van Tulleken’s intended audience.

A showdown in the final minutes with Tim Rycroft, the chief operating officer of the Food and Drink Federation, is the touch of extra rigour that is the Van Tulleken hallmark. Rycroft gives the standard line about needing to ensure people are empowered to make “good choices”. Van Tulleken pushes back about how much choice there is in an environment where everything – availability, price, marketing and so on – is designed to push the consumer one way. The killer moment comes when he asks which is the priority: profit or public health? “The priority is profit,” Rycroft says. A delicious moment and bitter truth at once.

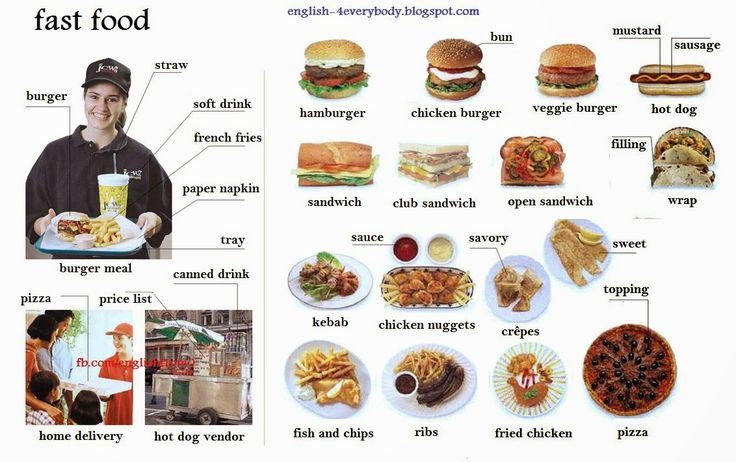

Watch out, people!: the fast food generation - BBC News Russian Service

- BBC London

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Journalists are sometimes called "forest nurses". It is hinted that they are, in fact, vultures. nine0011

Indeed, earthquakes and hurricanes, famine and death hit the front pages of newspapers, and calm and smoothness in good weather, where a happy family is chilling, cannot be dragged onto the pages of print.

Journalists have to compose quickly, from which common phrases often jump out from under their pen, which then cannot be removed from use by any means.

For example, an entire generation has been dubbed "angry young people". The other is the hippie generation. But that's in the past, but what about the current generation? He, too, was labeled. This is the generation of fast food, lost to normal food, and, therefore, normal life. nine0011

In numerous documentaries, the viewer is presented with horror pictures - a London school, whose students do not know what a cucumber or a tomato looks like.

When a famous chef, specially invited for this purpose, offers them a school lunch at the restaurant level, but without their favorite chips or sausages, the children do not eat, pushing aside French culinary delights with disgust.

The family, in which parents were shown by computer simulation what will happen to their children in 30 years, was horrified, but when it came to giving up the usual food, the offspring made a real tantrum. nine0011

Skip Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of story Podcast

They can be understood. Through numerous experiments on myself over many years, I came to the conclusion that our body operates on the principle of narcology and asks for what it is used to. If accustomed to fat, will ask for fat, and accustomed to the petals of nasturtium, then this will be desirable. nine0011

All changes happen very slowly, and only after overcoming several barriers and reaching a new level, you can understand what is left behind.

For example, by my frail example, I seduced a man, then young and impressionable, who, after four or five years of vegetarianism, admitted that half of his sores had gone away and that such a meager meal seemed to increase his strength.

God have mercy, I'm not agitating you - just in case. Because on a national scale, the habits of one person matter a lot. nine0011

This is exactly what is happening in Britain right now. An entire generation accustomed to processed foods will inevitably give rise to a variety of diseases that the National Health System will have to deal with.

And that, in turn, will be able to help not in eradicating the causes, but only in eliminating symptoms - in other words, it will relieve sores with medication.

Medicines, as you know, for the most part, have their own side effect, which also needs to be treated.

Firstly, I feel sorry for the people - but you can’t talk about this openly, you can get into trouble, and secondly, I feel sorry for society, because the taxes collected with such difficulty will go to people’s diseases, which are countless. It's no use blaming the industrial plants that produce all the convenient, fast, but dead food.

It's no use blaming the industrial plants that produce all the convenient, fast, but dead food.

First, they are only responding to the demand that is already there - if not them, then someone else will produce.

Secondly, the production of fast food is a consequence of the generally healthy capitalist tendency towards high labor productivity and the profitability of production that goes with it. nine0011

A profitable enterprise, having become rich, buys a non-profit one and remakes it in its own way.

For developed countries, the way out must be sought in the enlightenment of consciousness.

The rest - to rely on their underdevelopment.

Rejoice that there are vegetable gardens, impassability and general slovenliness.

They can save the state from food degeneration.

Mayor of London bans fast food ads on public transport to save children from obesity

Sign up for our Newsletter “Context”: it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, PA

Image caption,Ads for junk food will be banned on public transport in the UK capital

From the beginning of 2019, fast food ads on public transport will be banned in London.

Food and drink posters that are high in fat, salt and sugar will disappear from subways, skytrains, buses and bus stops. nine0011

London Mayor Sadiq Khan said he was trying to solve the problem of childhood obesity, which he called a "time bomb".

The Association of Advertising Agencies said the city's decision would have little effect on the broader societal problems that lead to obesity.

The ban will come into effect on February 25, 2019.

Image caption,The advertisers' association said passengers could be harmed by the ban

Where will the ban work?

Except on buses, tube trains and overground, fast food advertising will be prohibited on:

- Roads operated by the City of Transport for London, including road junctions and bus stops

- Taxi and chauffeur-driven rental cars

- Riverside public transport

- Trams

- Emirates Air Line lift and Victoria bus station

After plans to ban fast food advertising were first announced in May, 82% of those who took part in an online survey supported the idea, according to London City Hall. nine0011

nine0011

Sadiq Khan said that decisive action is needed to combat obesity among children.

Image caption,Fast food ads at a bus stop

"Reducing the exposure of junk food advertising is playing a role - not only for children, but also for the parents, families and caregivers who buy food and cook for children," the Mayor of London said.

"Passengers will suffer"

City Hall's plan is backed by child health experts, including Head of Medical England Prof. Dame Sally Davies, who called it an important step in the right direction. nine0011

- From Pepsi to Nivea: when advertising causes embarrassment

- Red panties and chopsticks: advertising campaigns that went wrong

- Sadiq Khan: the new mayor of London - who is he?

However, the Association of Advertising Agencies said that passengers could be affected by the ban.