Feeding babies real food

When, What, and How to Introduce Solid Foods | Nutrition

For more information about how to know if your baby is ready to starting eating foods, what first foods to offer, and what to expect, watch these videos from 1,000 Days.

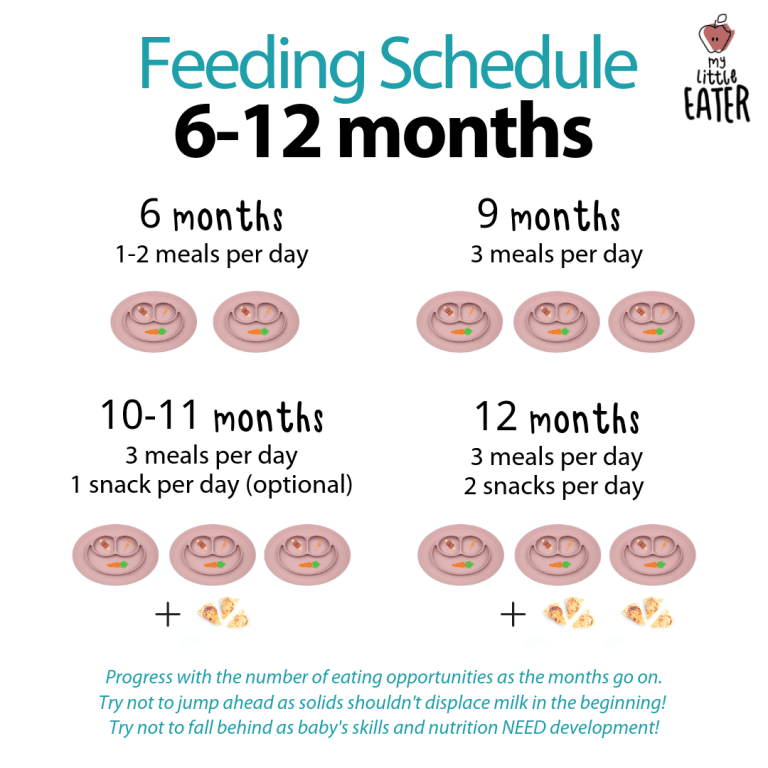

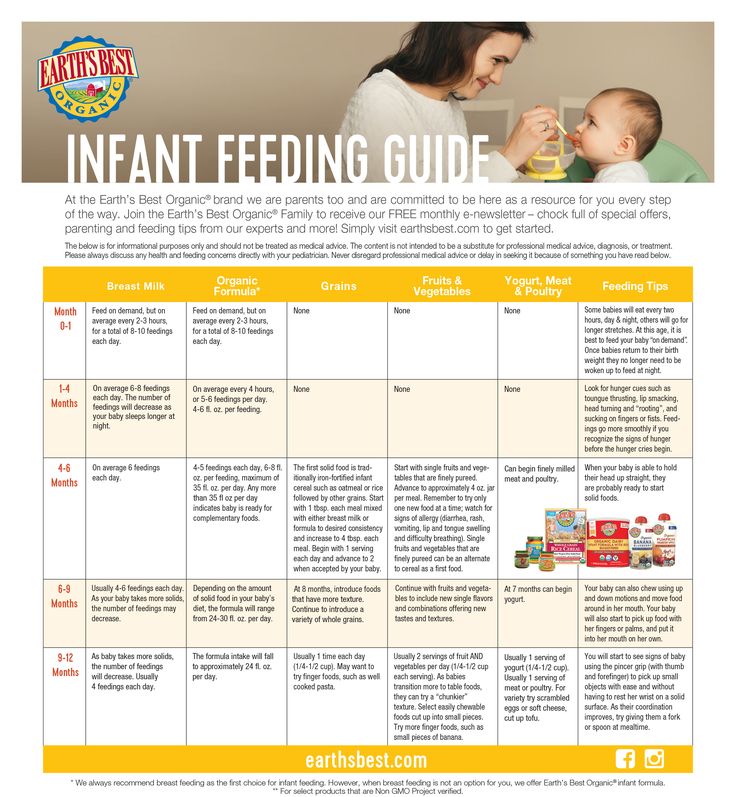

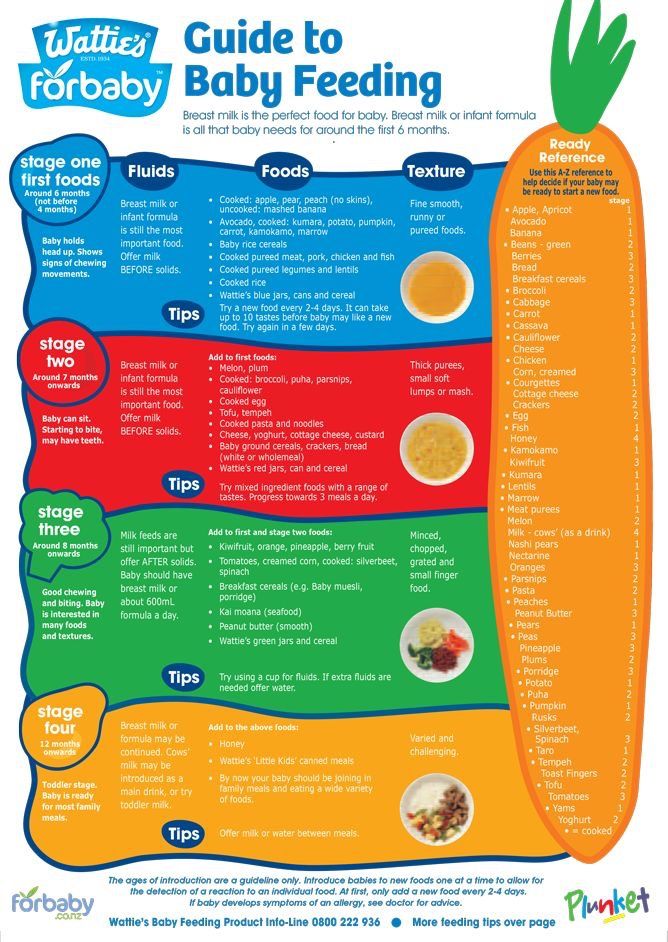

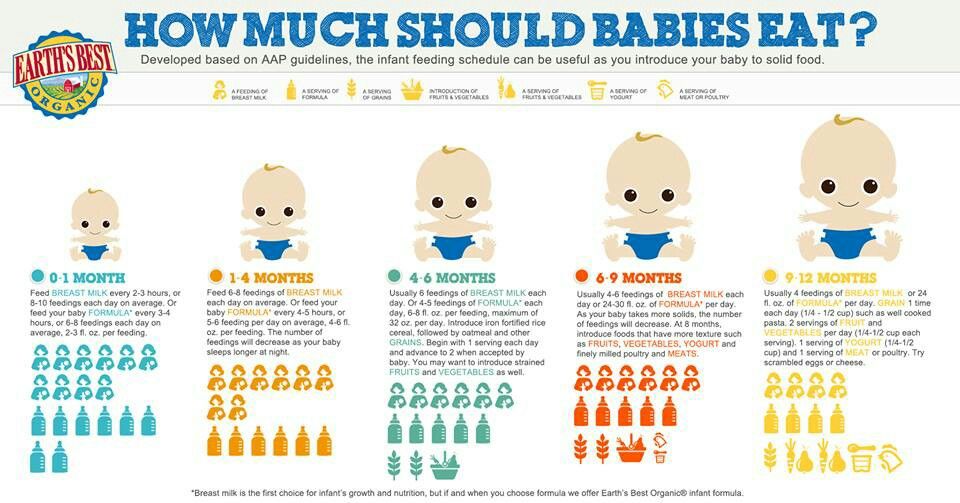

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend children be introduced to foods other than breast milk or infant formula when they are about 6 months old. Introducing foods before 4 months old is not recommended. Every child is different. How do you know if your child is ready for foods other than breast milk or infant formula? You can look for these signs that your child is developmentally ready.

Your child:

- Sits up alone or with support.

- Is able to control head and neck.

- Opens the mouth when food is offered.

- Swallows food rather than pushes it back out onto the chin.

- Brings objects to the mouth.

- Tries to grasp small objects, such as toys or food.

- Transfers food from the front to the back of the tongue to swallow.

What Foods Should I Introduce to My Child First?

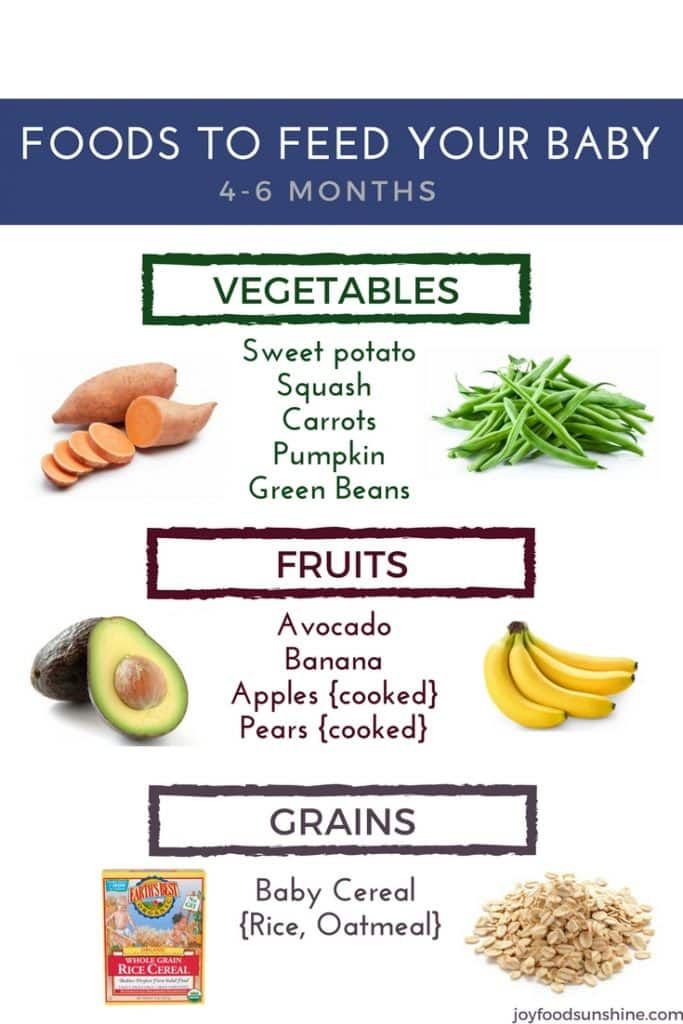

The American Academy of Pediatrics says that for most children, you do not need to give foods in a certain order. Your child can begin eating solid foods at about 6 months old. By the time he or she is 7 or 8 months old, your child can eat a variety of foods from different food groups. These foods include infant cereals, meat or other proteins, fruits, vegetables, grains, yogurts and cheeses, and more.

If your child is eating infant cereals, it is important to offer a variety of fortifiedalert icon infant cereals such as oat, barley, and multi-grain instead of only rice cereal. Only providing infant rice cereal is not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration because there is a risk for children to be exposed to arsenic. Visit the U.S. Food & Drug Administrationexternal icon to learn more.

How Should I Introduce My Child to Foods?

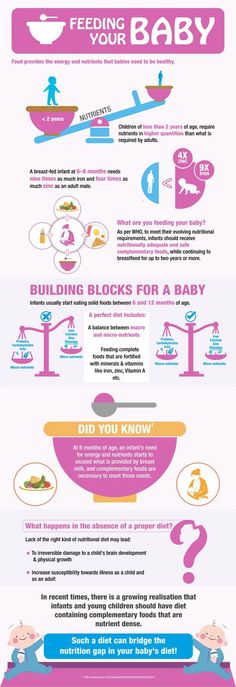

Your child needs certain vitamins and minerals to grow healthy and strong.

Now that your child is starting to eat food, be sure to choose foods that give your child all the vitamins and minerals they need.

Click here to learn more about some of these vitamins & minerals.

Let your child try one single-ingredient food at a time at first. This helps you see if your child has any problems with that food, such as food allergies. Wait 3 to 5 days between each new food. Before you know it, your child will be on his or her way to eating and enjoying lots of new foods.

Introduce potentially allergenic foods when other foods are introduced.

Potentially allergenic foods include cow’s milk products, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soy, and sesame. Drinking cow’s milk or fortified soy beverages is not recommended until your child is older than 12 months, but other cow’s milk products, such as yogurt, can be introduced before 12 months. If your child has severe eczema and/or egg allergy, talk with your child’s doctor or nurse about when and how to safely introduce foods with peanuts.

How Should I Prepare Food for My Child to Eat?

At first, it’s easier for your child to eat foods that are mashed, pureed, or strained and very smooth in texture. It can take time for your child to adjust to new food textures. Your child might cough, gag, or spit up. As your baby’s oral skills develop, thicker and lumpier foods can be introduced.

Some foods are potential choking hazards, so it is important to feed your child foods that are the right texture for his or her development. To help prevent choking, prepare foods that can be easily dissolved with saliva and do not require chewing. Feed small portions and encourage your baby to eat slowly. Always watch your child while he or she is eating.

Here are some tips for preparing foods:

- Mix cereals and mashed cooked grains with breast milk, formula, or water to make it smooth and easy for your baby to swallow.

- Mash or puree vegetables, fruits and other foods until they are smooth.

- Hard fruits and vegetables, like apples and carrots, usually need to be cooked so they can be easily mashed or pureed.

- Cook food until it is soft enough to easily mash with a fork.

- Remove all fat, skin, and bones from poultry, meat, and fish, before cooking.

- Remove seeds and hard pits from fruit, and then cut the fruit into small pieces.

- Cut soft food into small pieces or thin slices.

- Cut cylindrical foods like hot dogs, sausage and string cheese into short thin strips instead of round pieces that could get stuck in the airway.

- Cut small spherical foods like grapes, cherries, berries and tomatoes into small pieces.

- Cook and finely grind or mash whole-grain kernels of wheat, barley, rice, and other grains.

Learn more about potential choking hazards and how to prevent your child from choking.

Top of Page

Babies Eat Real Food: Getting Started with Baby-Led Weaning

So you want to feed your baby real food?

Then you need to know about baby-led weaning (BLW). BLW works wonders to expose babies to a variety of tastes, textures, temperatures, and the appearance of real foods.

BLW works wonders to expose babies to a variety of tastes, textures, temperatures, and the appearance of real foods.

The best part? It’s really simple. It involves giving a baby pieces of real food and letting them pick it up and self-feed. Easy-peasy.

Lots of newbies to BLW have questions, I am going to outline how we selected and prepared foods from 6 to 8 months of age. After 8 months, our kids went to eating the same food that we eat, therefore no special preparation was necessary (even though my daughter didn’t have any teeth until 10 months!).

There are many interpretations with how to progress each month and what to feed. Here is how we did BLW based on food types, motor skill development, and what worked for our family. For the record, I am a mother of two little ones with a Ph.D. in Child Development and a research focus in feeding

babies.

Want more research-based information on feeding babies?

Six Months: Fruits and Veggies.

Motor Skills: Fruits and Veggies are mostly served in very soft, overcooked sticks (3-4 inches long) and pieces of the size of the hand. The baby can easily grasp, pick up, hold, and nibble on these vegetables. Stay with sticks because chunks of food can be a choking hazard.

Here’s how a tray of roasted veggies would look prepped for a 6 month old.Food Prep Advice: At first, little hands can have a hard time getting a hold of pieces of food–it is just part of the fun. Some foods are easier to grab if they are steamed and others are better roasted.

Steam cauliflower and broccoli, and serve it frequently. These bitter flavors are the least preferred by babies, so it’s important to expose early and often. Never decide if your baby “likes” or “dislikes” something–it is far too early to tell. Those little taste buds are a work in progress and always evolving.

You will want to roast some of the slippery veggies—zucchini, carrots, sweet potato, red pepper, etc. The idea is to dry them out so they are easier to handle. They should be really soft and easy to chew–like a scrambled egg.

The idea is to dry them out so they are easier to handle. They should be really soft and easy to chew–like a scrambled egg.

If we are going to keep it simple–please don’t do this everyday. Chop up a variety, lay them out on a pan and cook them at the same time—then stick a few days worth in the fridge.

When feeding ripe, soft fruits (like pears and bananas) just give them to the baby in their whole form. Babies have a lot of fun gnawing away at whole fruits.

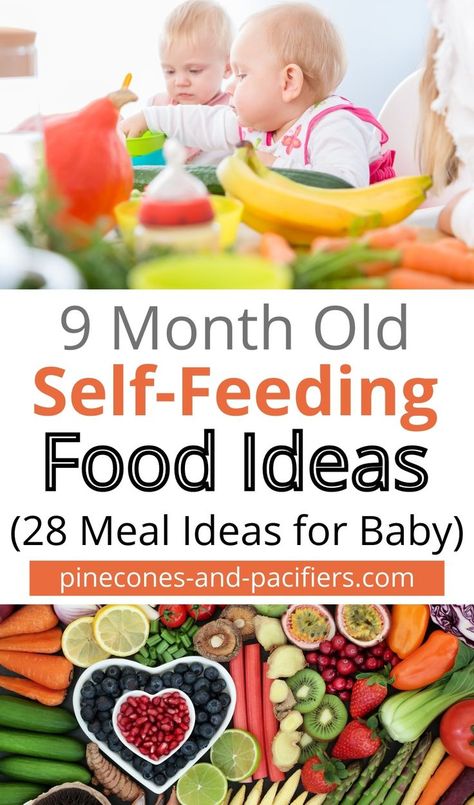

A six-month meal: Broccoli + Sweet PotatoesA six-month meal: Avocado + ZucchiniSeven Months: Fruits, Veggies, Grains, Legumes, and SpicesMotor Skills: You are going to notice your baby start to do more “raking”. This means taking the four fingers and raking them back towards the palm to scoop up food.

Raking opens up lots of doors.

They can now rake up things like quinoa, oats, beans, and lots of other less tasty small objects like paper clips and dog food. Try to continue serving sticks but add in some other foods they can self-feed and rake.

There is no way around it, raking is messy. But it’s important that they get the chance to self-feed.

Your baby will be on the fast track to the pincer grasp (picking up with the pointer finger and thumb), which brings some dignity to BLW. Also consider loading a spoon for him and handing it over so he can practice getting it in his mouth.

Food Prep Advice: Keep serving up all of the above and start mixing things together. Quinoa and frozen peas, oats and avocados, brown rice and beans, etc. I like to make a large batch of grains and keep it in the fridge, mixing it with different veggies each day.

I am a big fan of the early mixing of foods and not a fan of serving foods separately in plates with compartments. Foods touching one another is natural and should be encouraged. Add some spices to keep it interesting.

A seven-month meal: Quinoa + Peas (plus cumin and olive oil)Eight Months: Family dinner, game on.

Motor Skills: You will start to see some raking mixed with a little pincer action. The pincer grasp tends to emerge somewhere around the time that babies crawl (the hands get a lot of strengthening and stimulating that way)–so don’t worry if it is later. Your baby will be able to pick up almost anything you put in front of them with raking or pincer grip. If you have not already started doing so, try loading the spoon and fork and handing it to them to self-feed.

Food prep advice: This is where we got lazy. No more cooking separate food. At 8 months, they started eating everything we eat, but without salt. We do eat healthy, which made this transition easier. At this age we started to serve meat, but we are careful to only give hormone and antibiotic-free meats–which is a personal preference.

Rather than adding salt while cooking, I first scoop the baby’s food out and onto her plate, and then salt the rest for the grown-ups at the end. I swear by the Pampered Chef Kitchen Chopper. I can chop up her food the tiniest pieces, or leave them larger in a matter of seconds.

I swear by the Pampered Chef Kitchen Chopper. I can chop up her food the tiniest pieces, or leave them larger in a matter of seconds.

This is where my BLW advice ends, because we have now introduced real, grown up food that has lots of colors, textures, flavors, and temperatures. Don’t expect your baby to progress on the same path. There are many options to deviate and go in your own direction. Using purees for some meals and real food for others is fine—it is important that you find the right blend that works for your family.

Want more research-based information on feeding babies?

Proper diet for teenagers: what and how best to feed schoolchildren | 74.ru

A child will easily refuse school food, but you can fix it

Photo: Aleksey Volkhonsky / V1.RU

Share

Is your child okay with his grades? And what about nutrition? If for the last six months, thanks to quarantine, you could control it, then from September 1, the student’s menu is a lottery. Together with nutritionists, we check how to properly feed children and adolescents and what foods should be in the diet. nine0009

Together with nutritionists, we check how to properly feed children and adolescents and what foods should be in the diet. nine0009

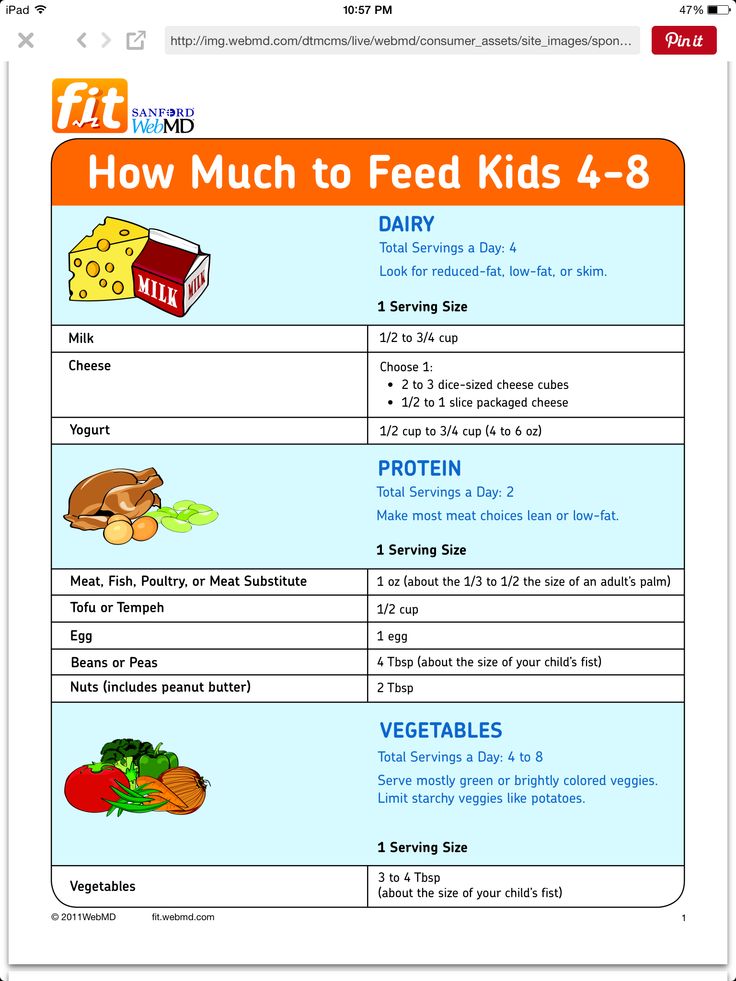

The main rule that must be followed when compiling a schoolchild's diet is balance. The menu of children and adolescents should contain all macronutrients, proteins, fats and carbohydrates in the right proportions. The norms developed by the World Health Organization help us to make the right proportion. It is better to calculate an individual nutrition formula for a child with a specialist, but you can write down a list of healthy foods that must be present in the diet now. nine0009

— Protein must be present in the child's diet. It is found in greater amounts in meat, fish, seafood, dairy products, eggs, nuts and legumes. Meat, fish, dairy products and eggs are more common foods for children, as they are present in the menu of kindergarten, school and are more often included in the main part of the home diet. So they are just the necessary minimum that, if possible, a child should receive, - says children's nutritionist Irina Pyshnaya. nine0009

nine0009

Irina Pyshnaya — doctor, children's nutritionist, consultant in the correction of eating behavior.

Children get used to meat, fish, dairy products and eggs from a very young age

Photo: Dmitry Gladyshev / Network of city portals (infographics)

Share

The next component is fat. Fats of both animal and vegetable origin should be present in the children's diet. The former are found in meat, fish and dairy products, the latter in vegetable oil, avocados and nuts. By adding butter, vegetable oil and fatty fish containing omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids to the student’s menu, you will close the minimum threshold for the child’s need for fats. nine0009

And the last macronutrient that the diet cannot do without is carbohydrates. This is the main source of energy, which should be supplied in sufficient quantities, but not in excess. This is important for maintaining a normal weight.

If there are too many carbohydrates, they will turn into a fatty layer

Photo: Dmitry Gladyshev / Network of city portals (infographics)

Share

are set individually, taking into account the age, physical development, health and taste preferences of the child. nine0009

When choosing protein foods for school meals, experts recommend giving preference to lean meat (beef tenderloin, veal, chicken breast and turkey breast, rabbit), but you can eat any fish - the one you like best, because any fish has healthy fats .

The cooking method plays a big role. Regardless of whether the child has weight problems or not, it is better to cook, stew, bake, steam or in a slow cooker food. Try to use less vegetable oil and a frying pan. In cooking, you can use natural seasonings, salt in moderation (or soy sauce) or prepare homemade sauces: with lemon juice, with tomato paste or tomatoes, on kefir or yogurt with greens. nine0009

nine0009

— It is better to divide dairy products into two groups: quality and dessert. High-quality “milk” includes those products that contain more protein, less unnecessary fats and sugar: cottage cheese up to 9% fat, sour cream up to 20%, cream, kefir, unsweetened yogurt, cheese, explains Irina Pyshnaya. — Dessert dairy products — sweet yoghurts, curd mass 23% fat, curd glazed curds with milk fat substitutes. The amount of these foods in the diet should be controlled, like sweets. nine0009

As for eggs, it is better to eat them no more than once a day, as this is not an easy product, and the issue of its content in the diet is decided individually. The method of preparation also matters - it is better to boil than to fry in a pan in vegetable oil.

Another important component of children's and adolescent diets is carbohydrates. And their most faithful sources are porridge. Choose those that saturate for a long time: buckwheat, oatmeal, millet, barley, barley, bulgur, brown, brown, wild rice. And read our review about the benefits of different types of cereals. nine0003

And read our review about the benefits of different types of cereals. nine0003

- More useful is brown, unpolished, wild rice, which retains its shell. It is rich in vitamins of groups B, PP, E, carotene, silicon. In addition, rice also contains lecithin and does not contain gluten, which is important for those who have an intolerance to it. Also, it is not in buckwheat porridge, which is considered a good source of proteins and carbohydrates, contains B vitamins, zinc, iron, copper, magnesium and calcium, explains dietitian Irina Toropygina. - But you need to understand that porridge is not a side dish, but a separate product that is better not to be abused. It is desirable to use it in the morning, for breakfast. Porridge can be consumed several times a week, preferably on days of physical activity. Because these are carbohydrates, and in order to spend them, some kind of load is needed. For breakfast, you can combine porridge with protein - yogurt, cottage cheese, cheese. nine0003

Irina Toropygina — dietitian of the highest category, specialist in DNA testing, areas of work: diagnosis and identification of the causes of overweight or underweight, development of an individual diet for the treatment of obesity and overweight, nutritional support for various eating disorders.

Do not forget about fruits in the children's diet. Take the ones that the child likes, but consider their number.

Fruit maximum for each child - 250 grams per day

Photo: Dmitry Gladyshev / Network of city portals (infographics)

Share

— Fruit is sugar. Sugar is a provocation of the pancreas to release insulin. The more sugar in the diet, the more frequent the release. The more likely it is to acquire a state of insulin resistance, including those extra pounds. Part of the unused energy sugar, neatly “decomposed” by insulin into cells, turns into fats and is stored in reserve,” says Irina Pyshnaya. - Among vegetables, it is worth focusing on fresh vegetables - more "complex" fiber. nine0009

All the vegetables listed here are the best source of fiber

Photo: Dmitry Gladyshev / City Portals Network (infographics)

Share

— Let's start with the fact that compote can be prepared in different ways. You can use sweet syrups for cooking, add a glass of sugar there, and then compote or fruit drink will not be inferior to juice in terms of calories and insulin response. Therefore, if you prefer compotes and fruit drinks for your child, cook them correctly! As little sugar as possible in the recipe, as many fresh berries or dried fruits as possible. And then you can definitely say that you are giving a healthy drink, - says Irina Pyshnaya. nine0009

You can use sweet syrups for cooking, add a glass of sugar there, and then compote or fruit drink will not be inferior to juice in terms of calories and insulin response. Therefore, if you prefer compotes and fruit drinks for your child, cook them correctly! As little sugar as possible in the recipe, as many fresh berries or dried fruits as possible. And then you can definitely say that you are giving a healthy drink, - says Irina Pyshnaya. nine0009

Juice is also different: packaged and freshly squeezed. Both of them are sugar. A glass of freshly squeezed juice (200 ml) contains the juice of at least four fruits, and a glass of packaged juice contains fruit concentrate and sugar, equal in amount to that of natural sugars in freshly squeezed juice. In both cases, the amount of sugar is large. Just think: even an adult cannot afford to eat four oranges at a time, but drinking their juice (sweetness) in one gulp is easy! Be careful: for a child, a glass of juice for the day is for the eyes. It is better to give it every other day or once a week, so as not to provoke the taste buds to get used to the sweet taste, and the pancreas to a sharp release of insulin. nine0009

It is better to give it every other day or once a week, so as not to provoke the taste buds to get used to the sweet taste, and the pancreas to a sharp release of insulin. nine0009

According to sanitary and epidemiological requirements, it is not allowed to repeat the same foods in the school ration on the same day or in the next two days. When the child is in school, it may still be possible to do this, but if it is distance learning, it turns out that parents need to cook different meals every day. But the set of necessary products is relatively small. To make it easier for adults to organize the child's nutrition, it is enough to always keep a minimum supply in the kitchen: meat and fish in the freezer, cereals, vegetables and fruits, fresh dairy products and eggs. And get ready to make preparations. nine0009

— Cut fish, meat into pieces of 100-150 grams. Put them in separate bags (you can make cutlets) and freeze. In this case, getting one piece of meat (cutlet), putting it in a double boiler and preparing a fresh dinner for the child will not be difficult, recommends Irina Pyshnaya. - Cereals and vegetables just need to be in the kitchen. Their preparation does not take much time. If desired, you can also make preparations for soup or second courses with vegetables (fried vegetables - frying or sauce, dressings for soups). nine0009

- Cereals and vegetables just need to be in the kitchen. Their preparation does not take much time. If desired, you can also make preparations for soup or second courses with vegetables (fried vegetables - frying or sauce, dressings for soups). nine0009

Different serving of dishes will help to expand the diet. For example, one day for breakfast you serve a boiled egg with a whole grain bread sandwich with vegetables, herbs and a piece of lightly salted salmon. The next day, you also lay an egg in the basis of breakfast, just cook an omelet with milk, mushrooms and green beans. The list of products is slowly growing, the diet is becoming more diverse. Don't take on everything at once. Start small and gradually build up the pace. If the child’s breakfast is strictly defined (porridge or a boiled egg with a sandwich), leave it as he likes. Get busy with lunch and new soup recipes. One new soup recipe a week will be enough. As soon as this recipe takes root in the main menu of the child, proceed to the next one. nine0009

nine0009

It would be ideal to get the school menu in hand and prepare homemade meals with this information in mind. But in most cases this is not possible. So parents have to move blindly. But you can always talk to your child and find out what they had for lunch at school, and adjust as you go.

- Ask him what he eats from the school menu and write it down. Often there is a situation when a child eats either one or the other. For example, "I eat breakfast, I don't eat lunch." “I eat buckwheat, but the cutlet is tasteless.” Or "I'm eating sausage, and the pasta is stuck together in a lump." “I drink tea, but I don’t eat a bun - I’m on a diet.” This information, firstly, will help you get to know your child better - this is never superfluous. You will learn about his taste preferences: what he recognizes and what he does not. And based on these data, you can adjust the home menu so that the overall diet is complete and balanced. For example, if you tracked that the child categorically refuses to eat meat at school, add it to the home menu. Do not count on the fact that he will eat something there sometime, - says Irina Pyshnaya. nine0009

Do not count on the fact that he will eat something there sometime, - says Irina Pyshnaya. nine0009

If your child does not eat at school, make arrangements with them to either eat a prepared snack after school or wait for a full meal. This is a very insidious time when a student can eat a lot of useless 500-calorie foods and knock down all his appetite. This mechanism is one of the most gross nutritional errors, and if repeated systematically, it can lead to a failure in eating behavior. So much so that a child can reach adulthood, but the habit cannot be abandoned.

Helping children develop healthy eating habits

Maureen M. Black, PhD, Kristen M. Hurley, PhD

University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA

, 2nd rev. ed. (English). Translation: August 2015

ed. (English). Translation: August 2015

The first year of a child's life is characterized by rapid age-related changes related to nutrition. As infants gain control of their own bodies, they move from the stage of sucking liquids in a recumbent or reclining position to the stage of eating solid foods in a sitting position. Oral motor skills are developed, moving from a basic "sucking-swallowing" mechanism based on breast milk or formula to a "chewing-swallowing" mechanism based on the consumption of semi-solid foods, gradually moving to more complex combined types of food. nine0114 1.2 When infants are already well regulated in their movements, they move from passive feeding, in which someone feeds them, to self-feeding, at least occasionally. The infant's diet is enriched: through the introduction of mashed potatoes and specially prepared foods, a transition is made from breast milk and formula for feeding to the family diet. By the end of the first year of life, children are already able to sit, chew and swallow on their own, consuming different types of food, learn to eat independently and move on to a diet and diet that is characteristic of the whole family. nine0003

By the end of the first year of life, children are already able to sit, chew and swallow on their own, consuming different types of food, learn to eat independently and move on to a diet and diet that is characteristic of the whole family. nine0003

As children make the transition to a family diet, the advice is not only about food, but also about nutrition. A variety of healthy foods improves the quality of the diet in the same way as early and regular recognition of new types of food by the child. Data on infants and young children aged 6 to 23 months, collected in 11 countries around the world, show a positive relationship between dietary diversity and nutritional status (nutritive status). nine0114 3 Teaching a child to consume fruits and vegetables during infancy and early childhood is associated with the adoption of these types of food at an older age. 4-6

Eating habits and preferences are formed in children at an early age. If children forgo nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables, mealtimes can become stressful or wrestling. As a result, children may be deprived of both the nutrients they need and healthy, understanding relationships between them and caregivers. Adults who are inexperienced or stressed, and those who themselves have unhealthy eating habits, need help to establish healthy and fulfilling eating behaviors in children during the meal. nine0003

As a result, children may be deprived of both the nutrients they need and healthy, understanding relationships between them and caregivers. Adults who are inexperienced or stressed, and those who themselves have unhealthy eating habits, need help to establish healthy and fulfilling eating behaviors in children during the meal. nine0003

Subject

Eating problems occur in 25% - 45% of all children, especially during the period when children learn new skills, and new types of food or expectations associated with eating them become real for them test. 7 For example, the period of infancy and early childhood is characterized by a desire for independence - children try to do everything on their own. When these characteristics are also applied to eating behavior, it suggests that children may be neophobic (fear of trying new foods) and insist on a limited set of foods consumed, 8 which further leads to the perception of these children as picky eaters.

Most eating problems are temporary and easily resolved with little or no intervention. However, when such problems continue for a long time, their presence can slow down the child's growth, development and worsen relationships with people caring for him. This leads to long-term problems with the health and development of the child. 9 Children with persistent eating problems may be at risk of developing growth and behavioral problems if caregivers do not seek help in a timely manner, allowing a critical situation to develop. nine0003

Issues

Eating habits are influenced by age, family or environment. As they mature and are able to make the transition to a family diet, their internal regulatory signals for hunger and satiety may be suppressed by family and cultural patterns. In families where adults lead by example in healthy eating, children are more likely to eat more fruits and vegetables than children in families where they do not. At the same time, in a family where it is customary to eat less healthy food, snacks are abused, children are likely to have eating habits and taste preferences characterized by the consumption of excess amounts of fat and sugar. nine0114 10 In terms of environmental influences, children's exposure to fast food restaurants and similar establishments has resulted in an increased intake of high-fat foods such as french fries, while not eating more nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables. 11 What's more, adults may not realize that many commercial products advertised as products for children (such as sugary drinks) can satisfy hunger or thirst but provide minimal nutritional intake. nine0114 12

At the same time, in a family where it is customary to eat less healthy food, snacks are abused, children are likely to have eating habits and taste preferences characterized by the consumption of excess amounts of fat and sugar. nine0114 10 In terms of environmental influences, children's exposure to fast food restaurants and similar establishments has resulted in an increased intake of high-fat foods such as french fries, while not eating more nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables. 11 What's more, adults may not realize that many commercial products advertised as products for children (such as sugary drinks) can satisfy hunger or thirst but provide minimal nutritional intake. nine0114 12

A number of nationwide studies have documented excessive consumption of high-calorie foods during early childhood, 13.14 while many children consume critically low amounts of fruits, vegetables and essential micronutrients. 15 By the time they enter primary school, many children get half their fluid intake from sugary drinks. 16 This eating habit is undoubtedly developed during early childhood and preschool age. The presence of these unhealthy eating habits (eating foods high in fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates; sugary drinks; eating limited fruits and vegetables) increases the likelihood of micronutrient deficiencies (such as iron deficiency anemia) and overweight in young children. nine0114 17

16 This eating habit is undoubtedly developed during early childhood and preschool age. The presence of these unhealthy eating habits (eating foods high in fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates; sugary drinks; eating limited fruits and vegetables) increases the likelihood of micronutrient deficiencies (such as iron deficiency anemia) and overweight in young children. nine0114 17

Scientific context

The process of eating is often studied through observations or adult reports of eating behavior. Some investigators rely on clinical study of groups of children with stunting or nutritional problems, others select children without any abnormalities for research.

Key questions

Key questions are about the development of eating habits from infancy through early childhood, and the ways in which children report feeling hungry or full. In addition, this includes studying the reasons why some children (so-called "picky eaters") have selective food preferences. Key challenges for caregivers and families are to find ways to promote healthy eating habits in young children, encourage children to eat healthy foods, and prevent problems with feeding and growth. nine0003

Key challenges for caregivers and families are to find ways to promote healthy eating habits in young children, encourage children to eat healthy foods, and prevent problems with feeding and growth. nine0003

Recent Research Findings

Attachment and Nutrition

Healthy eating habits develop in infancy as infants and their parents develop a partnership in which they recognize and interpret both verbal and non-verbal communication cues each other. This reciprocal process forms the basis for building an emotional bond or attachment in infants and caregivers that is an integral part of healthy social functioning. nine0114 18 If communication between a child and adults is disrupted, characterized by incoherent, unresponsive interaction, bonds of attachment can be unreliable, resulting in the process of eating can turn into unproductive, exhausting quarrels over food.

Infants who do not communicate clearly about their needs, or who do not respond to caregivers' attempts to teach them regular and predictable habits related to eating, sleeping, and playing, are at risk of developing regulatory problems associated with eating as well. nine0114 9 Premature or sick babies may react more slowly than full-term babies, making it more difficult for these babies to express feelings of hunger or fullness. Adults who do not recognize signs of satiety in their children tend to overfeed them, causing infants to associate satiety with frustration and conflict.

nine0114 9 Premature or sick babies may react more slowly than full-term babies, making it more difficult for these babies to express feelings of hunger or fullness. Adults who do not recognize signs of satiety in their children tend to overfeed them, causing infants to associate satiety with frustration and conflict.

Feeding in the context of the adult-child relationship

Variability in the context of the adult-child relationship during feeding is associated with feeding behavior and growth of the child. nine0114 19 Aspects of parental behavior and guardianship, which include factors of perception and understanding of the child's behavior, apply to the nature of feeding (Table 1). 20,21,22 Responsive feeding reflects an interaction-based behavioral pattern in which adults provide control and developmentally appropriate responses to a child's signals of hunger or satiety. The unresponsive feeding process is marked by a lack of reciprocity between adults and the child. This is characterized by parents being overly in control of the feeding process (by forcing the child to eat or limiting the child's diet), or by the fact that the child controls the feeding process (for example, requires a limited menu, or eats only after much persuasion), or by the fact that an adult ignores the child's signals, or cannot organize the correct diet (isolated feeding). nine0114 23.24

This is characterized by parents being overly in control of the feeding process (by forcing the child to eat or limiting the child's diet), or by the fact that the child controls the feeding process (for example, requires a limited menu, or eats only after much persuasion), or by the fact that an adult ignores the child's signals, or cannot organize the correct diet (isolated feeding). nine0114 23.24

parents and child are in a relationship where requirements are clearly expressed and there is a mutual interpretation of signals for feeding. Responsive feeding is characterized by short-term interaction based on behavioral characteristics and consistent with a certain stage of development of the child. In the course of this interaction, both sides easily compromise. nine0114 22,25,26

A controlling feeding style, well structured but low in caring, is characteristic of parents who use forceful or restrictive strategies to control the feeding process. A controlling feeding style is part of an authoritarian parenting model and may include overly assertive behaviors such as loud talking, force feeding, or other ways to get a child to do what they want. nine0114 27 Parents who control the feeding process can suppress the child's internal regulatory signals of hunger or satiety. 28 Infants' innate ability to self-regulate energy consumption disappears during early childhood due to the influence of family and cultural patterns. 29

nine0114 27 Parents who control the feeding process can suppress the child's internal regulatory signals of hunger or satiety. 28 Infants' innate ability to self-regulate energy consumption disappears during early childhood due to the influence of family and cultural patterns. 29

An indulgent feeding style characterized by a high level of nurturance and less structure is part of the indulgent parenting model. With this style of feeding, parents allow the child to decide for himself what to eat and when. nine0114 23 If the parents do not refer the child, the child is more likely to choose foods high in salt and sugar over a more balanced diet that includes vegetables. 23 Thus, an indulgent feeding style can be problematic given the genetic predisposition of infants to salty or sweet foods. 30 Babies whose parents practice indulgent feeding styles often weigh more than children of parents who use other feeding styles. nine0114 24

nine0114 24

A detached feeding style, characterized by both low levels of nurturance and a less structured structure, is common among parents with a lack of knowledge and involvement in their child's eating behavior. 23 A detached feeding style may have features such as lack of active assistance or verbalization during feeding, lack of rapport between parent and child, negative feeding environment, and lack of an orderly structure or defined feeding pattern. Indifferent parents often ignore both the feeding advice and the child's signals of hunger or satiety; they may not know what and when their child eats. Egeland and Sroufe 31 found that children of distant or psychologically unavailable parents were more likely to experience anxiety compared to children whose parents were actively involved in the process. Accordingly, a detached feeding style is an element of a detached parenting style. 23

Several recent systematic reviews have shown an association between parental control of feeding and weight gain in infants and young children and/or weight class. nine0114 24,32,33 Control feeding is associated with weight gain (eg, children whose parents have a restrictive feeding style tend to overeat) 34 and weight loss (eg, children who are forced to eat more do not tend to overeat). 35 However, the cross-sectional nature of most studies, coupled with a tendency to rely exclusively on parental behavioral data without considering the importance of interactions during feeding, makes it difficult to understand parent-child interactions during feeding. A recent double-blind study of infants in Australia found that adherence to preventive infant feeding guidelines led to normal weight gain and improved mutual understanding during feeding, as judged by the respondents. nine0114 36 More research is needed to better understand strategies for promoting healthy relationships that are important for a child's feeding and healthy growth.

nine0114 24,32,33 Control feeding is associated with weight gain (eg, children whose parents have a restrictive feeding style tend to overeat) 34 and weight loss (eg, children who are forced to eat more do not tend to overeat). 35 However, the cross-sectional nature of most studies, coupled with a tendency to rely exclusively on parental behavioral data without considering the importance of interactions during feeding, makes it difficult to understand parent-child interactions during feeding. A recent double-blind study of infants in Australia found that adherence to preventive infant feeding guidelines led to normal weight gain and improved mutual understanding during feeding, as judged by the respondents. nine0114 36 More research is needed to better understand strategies for promoting healthy relationships that are important for a child's feeding and healthy growth.

Food preferences

Children who grow up in families where parents set an example of healthy eating behavior (for example, eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables) develop similar food preferences. 4

4

Food preferences are also influenced by accompanying conditions. Children are more likely to avoid foods associated with unpleasant physical symptoms, such as nausea or pain. They may also avoid eating food associated with anxiety or distress caused by feeding disputes and confrontations. nine0003

Children also choose food based on qualities such as taste, texture, smell, temperature, or appearance, as well as environmental factors such as setting, presence of others, and perceived consequences of eating or not eating. For example, consequences of eating may include satiety, participation in a social function, or parental attention. Consequences of not eating can include things like extra play time, being the center of attention, or snacking instead of a normal meal. nine0003

The degree of familiarity with the taste of food increases the likelihood that the child will accept it. 37.38 Parents can make it easier to introduce new foods to their diet by regularly pairing them with familiar foods until the baby becomes familiar with the food.

Conclusions

Eating habits are formed early in development as a response to internal regulatory cues, parent-child relationships, dietary patterns, food offerings, and family behavior patterns. Teaching children to eat fruits and vegetables early in their development develops a lifelong preference for these foods. It is necessary to conduct research on the factors that determine the context of the relationship between an adult and a child in a feeding situation, at an individual level, in an interaction situation and at the level of the external environment. The relationship between responsive/non-responsive feeding styles and children's feeding behavior in relation to weight gain should also be explored, and population-specific tools to measure responsive/non-responsive feeding characteristics should be developed. nine0114 24

Eating behavior during early childhood largely depends on parents and is developed through the acquisition of experience with food and its use. A system of education and support involving health professionals (i.e. health visitors, family doctors and pediatricians) and nutrition programs should be established so that parents always have the opportunity to seek help with their child's eating behavior.

A system of education and support involving health professionals (i.e. health visitors, family doctors and pediatricians) and nutrition programs should be established so that parents always have the opportunity to seek help with their child's eating behavior.

Parents should combine their own meals with the feeding of the child in order to instill similar eating habits in him, and also to make the process of eating a pleasant experience for the child. Eating together allows children to watch their parents try new foods and helps them express feelings of hunger and satiety, as well as enjoyment of certain foods. nine0114 39

Parents control both the choice of food and the creation of a certain atmosphere in the process of feeding. Their "job" is to provide children with healthy food at fixed times and in pleasant surroundings. 39 By developing a certain diet, parents help children learn to consciously wait for the next meal. Children acquire the knowledge that the feeling of hunger will soon pass, and that they have no reason to be anxious or irritated. Children should not snack or eat throughout the day - this develops a sense of anticipation of a meal and the appearance of an appetite at a certain time. nine0114 39

Children should not snack or eat throughout the day - this develops a sense of anticipation of a meal and the appearance of an appetite at a certain time. nine0114 39

Meals should be a pleasant family event, when all family members eat together and discuss the events of the day. When the duration of meals is shortened (less than 10 minutes), children may not have enough time to eat, especially during the period when they are learning to eat on their own, and the process of eating slows down. At the same time, it is difficult for a child to eat food that lasts more than 20 or 30 minutes, so such food can cause a feeling of disgust.

When feeding is accompanied by distractions such as watching TV, family disputes, or other extraneous activities, it can be difficult for children to focus on food. Parents should separate meal times from play activities and avoid using toys, playing games, and not watching TV - all of these factors can distract the child from eating. Special equipment for children – high chairs, bibs and small utensils – encourages feeding and enables children to develop self-feeding skills. nine0003

Special equipment for children – high chairs, bibs and small utensils – encourages feeding and enables children to develop self-feeding skills. nine0003

Advice

Advice may be environmental, family or personal. In the environment, having healthy and tasty menus for young children at fast food restaurants can help avoid many of the problems associated with regularly eating high-fat foods (like french fries) instead of more nutritious foods like fruits and vegetables. Infant feeding recommendations should include the following information: information about the child's nutritional needs, methods to encourage healthy eating behaviors (including learning to recognize hunger or satiety signals and developing a specific type of interaction between parents and child during feeding), information on choosing the right time for about feeding, about ensuring regular feeding hours, about introducing new food into the diet through its modeling, data on ways to neutralize stressful and conflict situations during feeding. In terms of individual counseling, programs that help children develop healthy eating habits through nutrient-rich foods and develop the habit of eating to satisfy hunger rather than emotional needs can help prevent potential health and developmental problems. nine0114 40

In terms of individual counseling, programs that help children develop healthy eating habits through nutrient-rich foods and develop the habit of eating to satisfy hunger rather than emotional needs can help prevent potential health and developmental problems. nine0114 40

Literature

- Bosma J. Development and impairments of feeding in infancy and childhood. In: Groher M.E., ed. Dysphagia: Diagnosis and management . 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997:131-138.

- Morris SE. Development of oral motor skills in the neurologically impaired child receiving non-oral feedings Dysphagia 1989;3:135-154.

- Arimond M, Ruel MT. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: Evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. nine0178 The Journal of Nutrition 2004;134:2579-2585.

- Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, Ziegler P, Reidy K. Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predictary dietary variety in school-aged children? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2002;34(6):310-315.

- Schwartz C, Scholtens PA, Lalanne A, Weenen H, Nicklaus S. Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite . 2011;57(3):796-807.

- Mennella JA, Nicklaus S, Jagolino AL, Yourshaw LM. Variety is the spice of life: strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable acceptance during infancy. Physiol Behav . 2008;22;94(1):29-38.

- Linscheid TR, Budd KS, Rasnake LK. Pediatric feeding disorders. In: Roberts MC, ed. Handbook of pediatric psychology . New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:481-498.

- Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L. What kind of exposure reduces children's food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. nine0178 Appetite 1987;9(3):171-178.

- Keren M, Feldman R, Tyano S. Diagnoses and interactive patterns of infants referred to a community-based infant mental health clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2001;40(1):27-35.

- Palfreyman Z, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Development of the Parental Modeling of Eating Behaviours Scale (PARM): links with food intake among children and their mothers. Maternal and Child Nutrition . 2012 [Epub ahead of print].

- Zoumas-Morse C, Rock CL, Sobo EJ, Neuhouser ML. Children's patterns of macronutrient and intake associations with restaurant and home eating. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2001;101(8):923-925.

- Smith MM, Lifshitz F. Excess fruit juice consumption as a contributing factor in nonorganic failure to thrive. Pediatrics 1994;93(3):438-443.

- Ponza M, Devaney B, Ziegler P, Reidy K, Squatrito C. Nutrient intakes and food choices of infants and toddlers participating in WIC. nine0178 Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):71-79.

- Devaney B, Kalb L, Briefel R, Zavitsky-Novak T, Clusen N, Ziegler P. Feeding infants and toddlers study: overview of the study design.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):8-13.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):8-13. - Picciano MF, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL, Mitchell DC, Murray-Kolb L, McConahy KL. Nutritional guidance is needed during the dietary transition in early childhood. Pediatrics 2000;106(1):109-114.

- Cullen KW, Ash DM, Warneke C, de Moor C. Intake of soft drinks, fruit-flavored beverages, and fruits and vegetables by children in grades 4 through 6. American Journal of Public Health 2002;92(9): 1475-1477.

- Brotanek JM, Gosz J, Weitzman M, Flores G. Secular trends in the prevalence of iron deficiency among US toddlers, 1976-2002. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2008;162:374-81.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . New York: Psychology Press, 1978.

- Rhee K. Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning.

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2008;615:11–37.

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2008;615:11–37. - Baumrind D. Rearing competent children In: Damon W, ed. Child development today and tomorrow. San-Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; nineteen89:349-378.

- Maccoby EE, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, ed. Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development. Vol 4 . New York, NY: John Wiley; 1983:1-101.

- Black MM & Aboud FE. Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. Journal of Nutrition 2011;141(3):490-4.

- Hughes SO, Power TG, Fisher JO, Mueller S, Nicklas TA. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. nine0178 Appetite 2005;44(1):83-92.

- Hurley KM, Cross MB, Hughes SO. A systematic review of responsive feeding and child obesity in high-income countries.

Journal of Nutrition 2011;141:495-501.

Journal of Nutrition 2011;141:495-501. - Leyendecker B, Lamb ME, Scholmerich A, Fricke DM. Context as moderators of observed interactions: A study of Costa Rican mothers and infants from differing socioeconomic backgrounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development 1997;21(1):15-24. nine0301

- Kivijarvi M, Voeten MJM, Niemela P, Raiha H, Lertola K, Piha J. Maternal sensitivity behavior and infant behavior in early interaction. Infant Mental Health Journal 2001;22(6):627-640.

- Beebe B, Lachman F. Infant research and adult treatment: Co-constructing interactions . Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press; 2002.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO. Mothers' child-feeding practices influence daughters' eating and weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000;71(5):1054-1061

- Birch LL, Johnson SL, Andresen G, Peters JC, Schulte MC. The variability of young children's energy intake. New England Journal of Medicine 1991;324(4):232-235.

- Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition 1999;19:41-62.

- Egeland B, Sroufe LA. attachment and early maltreatment. Child Development 1981;52(1):44-52.

- DiSantis KI, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Fisher JO. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: a systematic review. nine0178 International Journal of Obesity 2011;35:480-92.

- Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obesity Research 2004;12(11):1711-1722.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003;78(2):215-220. nine0301

- Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Parental influences on young girls' fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes.