Parrot feed the baby

Psittacine Pediatrics: Housing and Feeding of Baby Parrots

Introduction

Hand-feeding baby birds is an vital part of any successful aviculture operation. Psittacine eggs that are artificially incubated or babies pulled from their parents at a young age, must be hand-fed for three to five months. Hand-fed birds make tamer companions and increase production if the parents re-clutch. Breeding pairs may neglect all or the youngest of their babies or they can cannibalise them. With these pairs there is no choice but to pull the babies and hand-fed.

Most exotic birds kept in captivity, such as psittacines and the many types of “soft bills” are altricial that is their young are hatched blind, helpless in food gathering and are unable to thermoregulate. Since poultry are precocial, little information on their relatively easy care is directly useful for parrots. Aviculturists have by trial and error methods, developed procedures to successfully raise hatchlings right from hatching.

Hygiene and Baby Movement

Nursery management must have as the main goal disease prevention. With chicks lacking fully developed immune systems, normal gut flora just becoming established, and parent pairs previously exposed to many different organisms, stress due to poor feeding or inadequate environment can quickly lead to disease. The nursery usually has a concentration of such susceptible individuals so there is greater chance of an epornitic occurring here, crippling the cash flow of an operation.

The flow of babies within a nursery can reduce the chances of cross-contamination. There should be no mixing of parent raised babies, even if the parents appear perfectly healthy and have been with the breeder for many years. Subclinical carriers of Psittacine beak and feather disease, polyomavirus and other diseases may transmit these vertically (via the egg) but with greater probably horizontally (directly) to babies in the nest. If these babies are pulled and not properly handled within the nursery, significant mortality could result. Increasing the number of hatchlings from artificially incubated eggs can minimize the chance of parent birds infecting their offspring.

Increasing the number of hatchlings from artificially incubated eggs can minimize the chance of parent birds infecting their offspring.

If parent fed chicks are to be hand-fed they should be pulled from the nest box before three weeks of age or the time of emergence of pin feathers on the wings. Older chicks will be stressed for the first few days in the strange nursery and may not want to be fed. However once they are hungry enough, usually about 12 hours later, they will accept hand-feeding.

Chicks to be hand-fed should be pulled from the nest box before three weeks of age or the emergence of pin feathers on the wings.Hands must be cleansed before and also between feeding and handling different babies and clutches. Disposable latex gloves can be changed between each group of babies or allow hands to be wiped with a disinfectant without irritating skin. Babies should not be removed from their containers unless necessary and a clean paper towel placed under each baby when weighing.

Food Preparation

A fresh batch of formula should be mixed up for each feeding. This is more hygienic and convenient since food does not need to be stored. To properly prepare the diet for feeding, a balance for weighing formula and accurate volumetric container for water should be used. Use accurate measuring devices, clean utensils and stir the food well.

Cooking time will vary slightly with model of microwave oven and type of container. Plastic containers seem to cool the food slower than ones made of glass. The final temperature of the food, just before feeding, should be slightly warmer than human body temperature or about 40°C (100°F). Be careful not to overheat the food as burning the babies can occur if the food contains hot spots or is only a few degrees too hot.

Table 1-

Water/Dry Mash Ratio of hand-feeding Formula

| Age of baby | Amount of dry mash | Volume of Water | |

| Hatching to 2 days | 1 tbs = 9 g (15 cc) volume rario 1:5 weight ratio 1:7 (12.  5% Solids) 5% Solids) | 72 ml | |

| 3 days to weaning | 1/2 cup = 64 g (120 cc) volume ratio 1:2 weight ratio 1:4 (20% Solids) | 240 ml |

Formulas for young babies, up to day two to four, should be significantly more diluted, about 5 to 10 percent solids. These young babies may also develop better on less rich diets having lower fat and protein and more easily digested carbohydrates (another area requiring research). Older babies should receive formula with a solid content in the 20 to 30 per cent range which usually results in a consistency a little thinner than apple sauce. Do not assume that such a texture represents the correct nutrient density as thickeners can make a formula with low dry matter levels appear much denser. Formula can be maintained at the correct feeding temperature by setting it in a bowl of hot water.

Formula food preparation for hand feedingMethods of Feeding

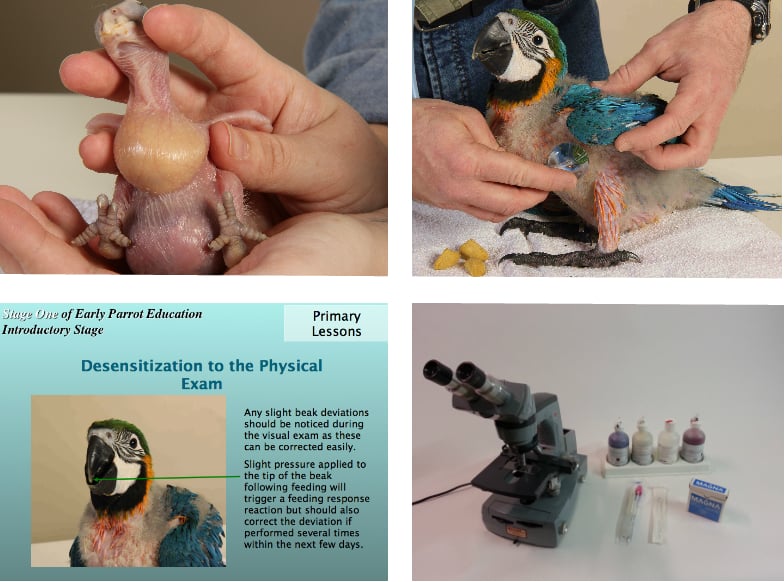

There are several possible techniques of feeding young parrots. Psittacine chicks produce a feeding response when the commissures of the beak are touched. This bobbing action closes the glottis and food passes into the crop. A bent teaspoon can be used to feed the formula but this can be a messy and time consuming way of feeding. Spoon feeding may produce a tamer bird because of the increased handling and is the preferred method of feeding of some of the most experienced aviculturists in the world (Low, 1987). However, there may be a greater chance of disease transmission with spoon feeding as the spoon is repeatedly touching the baby’s mouth and then dipped into the formula thus contaminating the food for the other babies.

Psittacine chicks produce a feeding response when the commissures of the beak are touched. This bobbing action closes the glottis and food passes into the crop. A bent teaspoon can be used to feed the formula but this can be a messy and time consuming way of feeding. Spoon feeding may produce a tamer bird because of the increased handling and is the preferred method of feeding of some of the most experienced aviculturists in the world (Low, 1987). However, there may be a greater chance of disease transmission with spoon feeding as the spoon is repeatedly touching the baby’s mouth and then dipped into the formula thus contaminating the food for the other babies.

Small plastic pipettes are used by some breeders to feed younger babies. Since these pipettes can only hold a few ml of food they require many repeated dippings into the food container with the same potential for disease spread as with spoons.

Catheter tipped syringes of various sizes are becoming popular instruments in feeding baby birds. Syringes can be used to slowly dribble the food into the mouth of the bird. Syringes allow the measuring of the amount of food fed and are easier to use. Silicone rubber and “O” ring syringes last longer than black rubber ones. Better still are syringes with no rubber gaskets and simply a concave round end. Soaking in tamed iodine disinfectant between feedings.

Syringes can be used to slowly dribble the food into the mouth of the bird. Syringes allow the measuring of the amount of food fed and are easier to use. Silicone rubber and “O” ring syringes last longer than black rubber ones. Better still are syringes with no rubber gaskets and simply a concave round end. Soaking in tamed iodine disinfectant between feedings.

Syringes are usually used to shoot the food into the crop of the bird. Hold the baby’s head loosely by placing a finger on both sides of the beak and the back of the head. Place the tip of the feeding syringe into the left side of the birds mouth and once the bird gives a feeding response (head pumping) shoot the food towards the back of the head. This procedure is relatively safe but requires some practice before it is done without a mess. The advantage of syringes is that a separate one can be used for each clutch of babies so that if one pair produces diseased offspring it doesn’t spread to the other babies.

A short soft rubber tube can be attached to the tip of the syringe which can then be placed further back into the mouth to prevent food going down the trachea. However this may have a behavioral effect on the baby and may prolong the weaning process since this is the least natural of all the feeding methods.

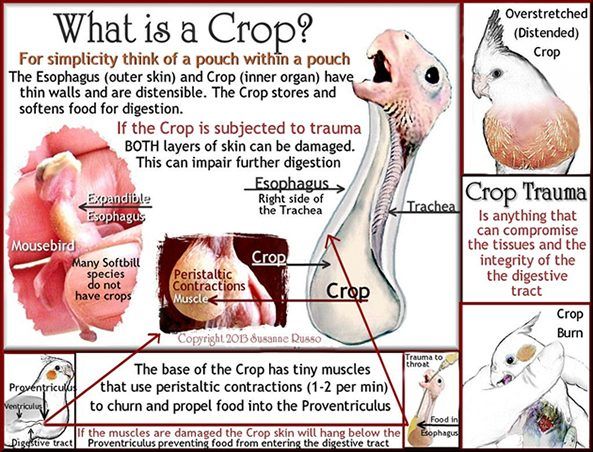

Fill the crop well without over stretching it and allow it to completely empty between feedings. Do not confuse the small pouch of loose skin around an empty crop as a crop that still contains food. Babies have looser skin around the crop to allow it to stretch out. Sick babies are more likely to aspirate themselves and the crop becomes flaccid. These babies should be placed in small containers, like disposable plastic cups, which hold them up prevent them from falling on their crop. Feeding frequency or gut transit time is dependent on the percent solids of the formula, its digestibility and caloric density. Babies less than 3 days old get fed six times a day and older ones 4 times a day.

Metal feeding tubes are only necessary when force feeding sick birds.

Whatever implements are used they should be disinfected between feedings and replaced periodically. Some aviculturists boil syringes in large pressure cookers or in regular pots but more commonly cold disinfectant baths are used to soak feeding equipment. Gluteraldehyde based products appear the strongest disinfectants however quartenary ammonium compounds or iodophors are acceptable under normal conditions. Phenol based disinfectants are very irritating to skin and chlorhexidines do not effectively kill pseudomonas bacteria which are common in wet environments and water. At HARI we lost several two month old cockatoos to pseudomonas when we used chlorhexidine to disinfect syringes. The bacteria were cultured directly from the syringes and upon close examination colonies could be seen in the corners of the syringe shafts.

HOUSING BABIES

Brooders and Containers

There are as many different and successful baby brooders as there are hand-feeding formulas. Some are homemade wooden boxes with electric elements or lights to keep the babies warm. Others are adapted metal game chick brooders or glass aquariums with custom made heaters to partially cover the top or bottom of the tank. Brooders set up with heating pads often result in cooked babies, thermal injuries or cold babies since precise, constant temperature maintenance is difficult (Stoddard, 1988). Another problem with homemade or adapted brooders is their usual lack of humidity control. Human baby incubators and specific commercial baby bird brooders have more accurate temperature and humidity control but are difficult to obtain or can become expensive when many babies have to be housed.

Some are homemade wooden boxes with electric elements or lights to keep the babies warm. Others are adapted metal game chick brooders or glass aquariums with custom made heaters to partially cover the top or bottom of the tank. Brooders set up with heating pads often result in cooked babies, thermal injuries or cold babies since precise, constant temperature maintenance is difficult (Stoddard, 1988). Another problem with homemade or adapted brooders is their usual lack of humidity control. Human baby incubators and specific commercial baby bird brooders have more accurate temperature and humidity control but are difficult to obtain or can become expensive when many babies have to be housed.

Brooders should be relatively small as an important part of disease prevention with babies is to keep clutches separate and this is limited with large brooders. They should provide constant, even heat that can be finely adjusted, be well ventilated, easily cleaned and have a water receptacle to add humidity.

One set-up which meets many of these requirements uses small aquariums to contain babies which is then placed a much larger aquarium or plastic pan filled with about three or four inches of heated water. The water is maintained at 40°C (100°F) with a submersible thermostat aquarium heater. Salt should be added to the water to keep down the growth of pseudomonas and other pathogenic bacteria. Evaporated water must be replaced so that the horizontally laid heater remains submerged.

Bedding

Young babies, less than two weeks of age, can be kept on paper towels in plastic cups, re-used yogurt containers or small aquariums. Babies should be sitting on clean and dry bedding which is therefore changed at each feeding. This may not provide firm enough footing for some birds which should be transferred onto paper or wood shavings or towels to avoid splayed legs. When babies are two-three weeks old, we transfer the babies to a small plastic containers that contain a few layers of newspaper under a few inches of wood shavings. Corn cob, walnut shell and pellet type bedding are not popular or losing favour with aviculturists because of various drawbacks.

Corn cob, walnut shell and pellet type bedding are not popular or losing favour with aviculturists because of various drawbacks.

Some babies may have a tendency to eat shavings, perhaps as a result of other complications such as calorie deficient diets or excess heat. Using towels has the advantage of being able to clearly see the baby’s droppings but the feet and feathers can get caked up with feces and time and energy must be spent on washing towels. Disposable diapers are expensive and wasteful. Babies stay cleaner when they are kept on processed paper product or shavings.

Temperature

The ambient temperature and humidity of baby altricial birds must be regulated. Young, up until they are feathered out, need supplemental heat above room temperature to thrive and even survive. Chilled babies, either because of neglectful parent birds or power failure to the brooder heater, will deteriorate quickly. These chicks may die later even after being warmed up. Nursery room temperature should be kept warm between 78 and 82 degrees fahrenheit.

The brooder temperature for recently hatched chicks can remain at the hatching temperature of 35.0°-36.5°C (96°-98°F) for the first few days. Once the baby is eating more solid food, at about 2-3 days of age, it should be kept at a lower temperature of 33.5°-35.0°C (92°-96°F) depending on the species and its metabolism. From there up to about two weeks of age babies should be in an environmental temperature of 32.0°-33.5°C (90°-92°F) (Table 2). If temperatures are to high the chick may exhibit panting, unrest, hyperactivity and have dry, reddened skin (Clubb and Clubb, 1986). Cold temperatures may result in death, poor gut motility, crop stasis or other digestive disorders, failure to feed or beg, inactivity or shivering (Clubb and Clubb, 1986).

Table 2-

Approximate Brooder Temperature

| Age | Temperature °C | Temperature °F |

| Hatch to Day 2-3 | 35. 0-36.5 0-36.5 | 96-98 |

| Day 3 to Day 14-21 | 31.1-34.0 | 88-94 |

| 3 weeks to Weaning | 25.0-30.0 | 76-86 |

Humidity

Natural nesting cavities in wooden tree trunks probably have a high relative humidity. Moist droppings from any babies within them will add to this, resulting in an environment of high humidity. These are unfortunately not the humidity levels found in most nursery brooders (Clipsham, 1989b). Most babies are traditionally raised on dry heat with heating pads, light bulbs or electric coils.

A range of 55-70% humidity produces quieter, fatter babies with a greater growth rate than those kept at levels of 15-35% (Clipsham, 1989b). Ambient humidity for hatching eggs and hand fed chicks can be increased by increasing nursery room humidity and, more effectively, by using containers of water as a source of both heat and humidity. A small aquarium submerged in and surrounded by a water bath heated by a submersible aquarium heater is very effective for eggs and up to one week old babies.

Identifying the Chicks

Babies must be properly identified in order to follow the linage and pair unrelated birds in the future. If considerable numbers of birds are being raised it becomes difficult to maintain the identity of similar babies from different parents. Several companies make closed leg bands in many different sizes. These bands can only be slipped to the birds leg when their feet are a small size. The best time to apply the bands is at about 2 – 3 weeks of age. Place the three larger toes through the appropriate sized band and then slide the band over the small inside toe which is held back against the foot.

Microchips implants are now available but are not yet commonly used for identifying baby birds.

Record Keeping and Growth Rates

The goal of any exotic aviculture venture is to raise healthy babies with minimum losses. Thus achieving the fastest growth rates possible on a particular formula are not as critical as the proper development of the baby. Average weight gains for the particular diet being used do help to monitor the development of individual babies. Weights taken each morning before the first feeding are less influenced by residual food still in the gut of the bird from the previous feeding as babies are usually allowed to empty over night. The time between feedings should slowly lengthen as the baby gets older but any sudden slow down in digestion is an indication of illness.

Average weight gains for the particular diet being used do help to monitor the development of individual babies. Weights taken each morning before the first feeding are less influenced by residual food still in the gut of the bird from the previous feeding as babies are usually allowed to empty over night. The time between feedings should slowly lengthen as the baby gets older but any sudden slow down in digestion is an indication of illness.

Stoddard (1988) monitors the health and development of young babies by the;

- Plumpness of the toes, wings and rump.

- Skin colour – should be a flesh-toned pink.

- Skin texture – should be translucent and soft.

- Anatomical symmetry – malnourished babies often have thin feet, toes, and wings as well as a disproportionately large head.

Flammmer (1986) lists other physical characteristics of nestling psittacines.

Complications

1 – Crop Stasis

The crop should completely empty between feedings. Food that remains in the crop too long may “sour” and provide an excellent growth media for opportunist bacteria and fungi.

Food that remains in the crop too long may “sour” and provide an excellent growth media for opportunist bacteria and fungi.

Hard lumps may form in the crops of some babies if the solid matter of the hand feeding formula separates from water. Treatment consists of feeding a little warm water and massaging the crop/lump until it is dissolved. The next feeding should consist of diluted formula following which the crop should be back to normal.

Your avian veterinarian should be consulted immediately should the crop content not empty as a crop wash can be performed by an experienced pediatric care technician or veterinarian to remove the soured content and the chick evaluated to determine what is the cause of the crop disorder and possible medical or therapeutic intervention.Under feeding may result in result in some babies ingesting bedding material. In a case of eclectus parrots ingesting wood-shavings they all died due to the gizzard damming up, preventing normal digestion (Smith, 1985).

2 – Crop Burn

If the temperature of the food is greater than 41°C (105°F) it may scald the crop and cause necrosis and fistulation (Giddings, 1986). Even with careful mixing and cooking some of the most experienced facilities may burn babies’ crops by feeding hot formula. Microwaves are usually used when overcooked food is fed. Hot areas within the food may go undetected even with a thermometer. It is best to let the formula stand for a minute, mix well and double check the temperature.

3 – Constricted Toes

Avascular digital necrosis or “big toe” is seen in baby macaws, eclectus and african greys. A ring of fibrous tissue may be initiated by rapid loss of body fluids from a crack of skin and encircles the toe leading to a constriction (Clipsham, 1989b).

Higher ambient humidity levels are reported to decrease this problem (Clipsham, 1989b; Joyner, 1987).

4 – Aspiration

On several occasions very young, less than 3 days old, weak babies were accidentally aspirated at HARI. This may have been due to poor feeding responses and force feeding. It is also possible to drop a baby onto its full crop resulting in the food being forced out and into the buccal cavity. The baby, not expecting food at that time may aspirate it. Feeding older birds by a tube placed into the crop will decrease the likelihood of aspiration in the more difficult species to feed (Joyner, 1987), such as 2 month old cockatoos.

This may have been due to poor feeding responses and force feeding. It is also possible to drop a baby onto its full crop resulting in the food being forced out and into the buccal cavity. The baby, not expecting food at that time may aspirate it. Feeding older birds by a tube placed into the crop will decrease the likelihood of aspiration in the more difficult species to feed (Joyner, 1987), such as 2 month old cockatoos.

5 – Beak Deformities

At HARI a lateral beak deformity has occurred in a baby macaw and an ingrown upper beak in a cockatoo. These types of deformities have been observed with other aviculturists (Joyner, 1987; Clubb and Clubb, 1989). The etiology of these deviations is not known but may be related to unnatural feeding methods or poor nutrition. The rapid growth and strong feeding response of macaws may exacerbate any deviations in growth.

6 – Bacterial, Fungal and Viral Diseases

Gram negative bacteria such as E. coli, Klebsiella sp., and Pseudomonas sp., are commonly considered pathogens and are often associated with disease (Clubb and Clubb, 1986). The “normal” aerobic alimentary tract flora for baby psittacines may include Lactobacillus sp., Staphylococcus eipdermidis, Streptococcus sp., Corynebactrium sp. and Bacillus sp. (Drewes, 1983). Candidiasis, caused by Candida albicans, is a yeast infection, usually of the crop. It is often a secondary problem associated with slowing of gut transit time. Digestive function may be upset by bacterial infections or blockage of the crop opening with foreign matter such as bedding substrate. Food which remains in the crop too long may begin to ferment leading to a “sour crop”. Dietary causes of a slow down in the digestive tract include food too cold, food with inadequate moisture content or ability to hold water (gelatin quality), food too high in fat or protein or too low in fiber. Babies will often vomit if one of these is not quite right.

Babies will often vomit if one of these is not quite right.

Abnormally high Candida infections in Palm Cockatoos may have been due to the simple sugars in the sweetened applesauce and sugar ingredients of the diet used by the New York Zoological Society (Sheppard and Turner, 1987).

Viral diseases can be prevented by only handfeeding incubator hatched babies and leaving parentally hatched nestlings with their parents. A separate nursery for babies exposed to parental feedings could be another alternative.

Weaning

Weaning appears not to be a learned process and occurs at a certain age which is not affected by external stimulation of hunger (Roudybush, 1986). Cockatiel chicks which reach a higher maximum weight sooner also wean earlier than chicks which do not gain more than their normal adult weight (Roudybush, 1986). Babies may lose weight (up to 10-15%) during weaning although keeping weight on them is probably better for birds to be shipped out unweaned.

When the babies have about an inch of blood left in their wings they are transferred to a cage which has small openings on the bottom wire for the babies to walk on comfortably. Perches should initially be near the bottom of the cage for the uncoordinated fledglings.

Perches should initially be near the bottom of the cage for the uncoordinated fledglings.

Once babies have absorbed the blood in their wing feathers they are ready to be placed into a cage. The cage should be large enough to allow the birds to exercise their wings. Perches are better placed near the bottom of the cage where young birds first spend most of their time. A cup of formulated parrot food, moistened with hot water, appears to be easier for babies to wean onto than seeds or hard vegetables. This cup must be made fresh daily (or more often in hot climates) to avoid spoilage and should be placed near where they perch.

To assist in weaning, feed a little amount of formula with a spoon from the cup that the birds should begin to eat from. Additional syringes of food should be given two or three times a day so they do not lose do much weight but avoid always feeding when babies beg or this behaviour may increase.

Potential for Breeding

There is concern that hand-rearing imprints the birds on humans and they will therefore not be suitable for breeding when they become sexually mature. Third generation breeding of Amazona leucocephala by Ramon Noegel indicates that this is not the case. Hand-reared birds often mature and breed in a shorter period than it takes wild-caught adults to settle down. Captive raised birds lack the stress that causes wild birds not to breed or abandon their nests.

Third generation breeding of Amazona leucocephala by Ramon Noegel indicates that this is not the case. Hand-reared birds often mature and breed in a shorter period than it takes wild-caught adults to settle down. Captive raised birds lack the stress that causes wild birds not to breed or abandon their nests.

If the babies birds are to be kept for breeding it is probably better to raise them in groups rather than individually.

Research with cockatiels has shown that early rearing experience is important for males to learn characteristics of the opposite sex, and for males and females to learn characteristics of nest-sites (Myers et al., 1988).

Care of Baby Parrot

Environment

A newly arrived baby parrot should be kept in a warm and quiet place for the first few weeks. A young bird needs to rest during the day and a busy environment may exhaust it. This stress weakens the immune system which may result in disease(s).

Provide your bird with a cage big enough so it can fully expand its wings and perhaps jump between perches. Parrots like to climb around their cage and like its security when they rest. Place several toys in its cage, to avoid boredom and change these regularly.

Parrots like to climb around their cage and like its security when they rest. Place several toys in its cage, to avoid boredom and change these regularly.

When outside of its cage, you can put your bird on a T perch but this should not be its only territory, since it cannot move around much.

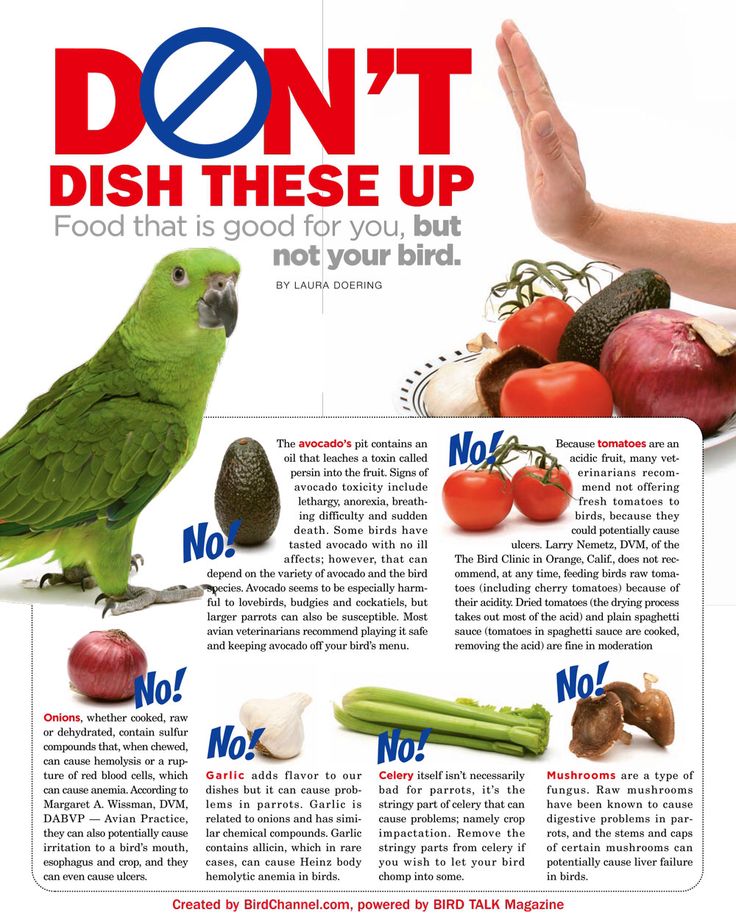

Feeding

A sudden change of diet could lead to weight loss and digestive upset with subsequent problems, so, it is best to continue with the same diet.

If the baby bird is not weaned, follow the directions on the leaflet of the Tropican hand-feeding formula and provide three food bowls to the baby: one filled with dry Tropican granules, one with soft Tropican moisten with warm water, and a bowl of fresh water. Moist food spoils very fast; so be sure to clean the bowl twice a day. Always use the same bowls for your baby birds unless bowls used by another bird has been thoroughly disinfected.

Exercise

The bird should be allowed out of its cage to interact with people and to exercise each day. Play with the baby every day but do not spoil it too much initially or it will demand this attention later. Do not leave doors or windows open or go outside with an unclipped bird. You can clip the wing feathers but when doing this for the first time, ask someone who is familiar with clipping.

Play with the baby every day but do not spoil it too much initially or it will demand this attention later. Do not leave doors or windows open or go outside with an unclipped bird. You can clip the wing feathers but when doing this for the first time, ask someone who is familiar with clipping.

Medical Care

Captive bred birds are not used to the microorganisms carried by a wild caught exotic bird and you should avoid the contact between the two. Species susceptible to Pacheco and Pox diseases should be vaccinated against them if they will be in places with other birds at proximity such as in a pet shop, veterinary clinic, boarding facility or bird shows.

If your bird shows one or several of the following symptoms, it may be sick: sleeping during its usual peak activity, not eating or eating less than usual, diarrhea and feathers puffed up. In that situation, contact immediately your usual avian veterinarian. Isolate the bird. Keep it warm (30°C – 86°F) and try to give it some food.

References

BUCHER, T.L. (1983). Parrot eggs, embryos, and nestling: patterns and energetics growth and development. Physiol. Zool. 56 465-483.

CACCAMISE, D.F. (1975). Growth rate in the Monk Parakeet. The Wilson Bulletin 88 495-497.

CLIPSHAM, R. (1989a). Pediatric management and medicine. Avian Veterinarians. 1:10-13.

CLIPSHAM, R. (1989b). Preventive Aviary Medical Management. Proceedings of the American Federation of Aviculture Veterinary Seminar, pp 15-28.

CLUBB, S. L., and CLUBB, K. J. (1986). Psittacine pediatrics. Proceedings of the Association of Avian Veterinarians pp 317-332.

CLUBB, S.L. and CLUBB, K.J. (1989). Selected problems in psittacine pediatrics. Proceedings of the American Federation of Aviculture Veterinary Seminar, pp 29-35.

DREWES, L., and FLAMMER, K. (1983). Preliminary data on aerobic microflora of baby psittacine birds. Proceedings of the Jean Delacour/ IFCB Symposium on Breeding Birds in Captivity, pp 73-81.

FLAMMER, K. (1986). Pediatric medicine. In: Clinical Avian Medicine and Surgery: including aviculture. Eds. G. J. Harrison and L. R. Harrison, W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, pp 634-650.

(1986). Pediatric medicine. In: Clinical Avian Medicine and Surgery: including aviculture. Eds. G. J. Harrison and L. R. Harrison, W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, pp 634-650.

GIDDINGS, R. F. (1986). An avoidable cause of crop necrosis in nestling cockatiels. Veterinary Medicine 81:1025-1026.

JOYNER, K.L. (1987). Avicultural Pediatrics. American Federation of Aviculture Veterinary Seminar pp 22-33.

JOYNER, K.L. (1988). The use of a lactobacillus product in a psittacine hand-feeding diet; its effect on normal aerobic microflora early weight gain, and health. Proceedings Association of Avian Veterinarians pp 127-137.

LOW, R. (1987). Hand-Rearing Parrots. Blandford Press. Dorset, U.K.

MOSTERT, PETER (1989). Personal communication.

MYERS, S.A., MILLAM, J.R., ROUDYBUSH, T.E. and GRAU, C.R. (1988). Reproductive success of hand-reared vs. parent-reared cockatiels (Nymphicus Hollandicus). The Auk 105:536-542.

SHEPPARD, C. and TURNER, W. (1987). Handrearing Palm Cockatoos. AAZPA Annual Proceedings pp. 270-278.

AAZPA Annual Proceedings pp. 270-278.

SILVA, T. (1989). A monograph of endangered parrots. Hand-rearing. Silvio Mattacchione and Co., Pickering, Ontario, pp 23-26.

SMITH, G. A. (1985). Problems encountered in hand-rearing parrots. In: Cage and Aviary Bird Medicine Seminar, Australian Veterinary Poultry Association. pp 71-77.

SMITH, R.E. (1986). Psittacine beak and feather disease: a cluster of cases in a cockatoo breeding facility. Proceedings Association of Avian Veterinarians pp 17-20.

STODDARD, H.L. (1988). Avian Pediatric Seminar. Avian Pediatric Seminar Proceedings (Supplement) pp 1-19.

TAKESHITA, D.L., GRAHAM, L. and SILVERMAN, S. (1986). Hypervitaminosis D in baby macaws. Proceedings Association of Avian Veterinarians pp 341-346.

THOMPSON, D.R. AND BARBER, L. (1983). Successful techniques for hand raising young psittacine birds. Proceedings of the Jean Delacour/ IFCB Symposium on Breeding Birds in Captivity, pp 171-178.

By Mark Hagen, M. Ag.

Ag.

Director of Research

How To Take Care of A Baby Parrot (from Hatchling To Juvenile)

(Last Updated On: November 11, 2022)

Caring for baby parrots (chicks) is a rewarding experience, but it requires knowledge and commitment. Baby parrots shouldn’t be purchased until they’ve been weaned to avoid health complications.

Once weaned, baby parrots should be fed soft seeds, fruits, and vegetables until they’re old enough to eat pellets and dried seeds.

They must be kept at a temperature of 65 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

When choosing a cage, ensure the bar spacing isn’t too wide. Provide perches of varying widths and position them throughout the cage.

Wild parrots care for their young for at least a year, which involves more than feeding as parrots teach their chicks how to become independent.

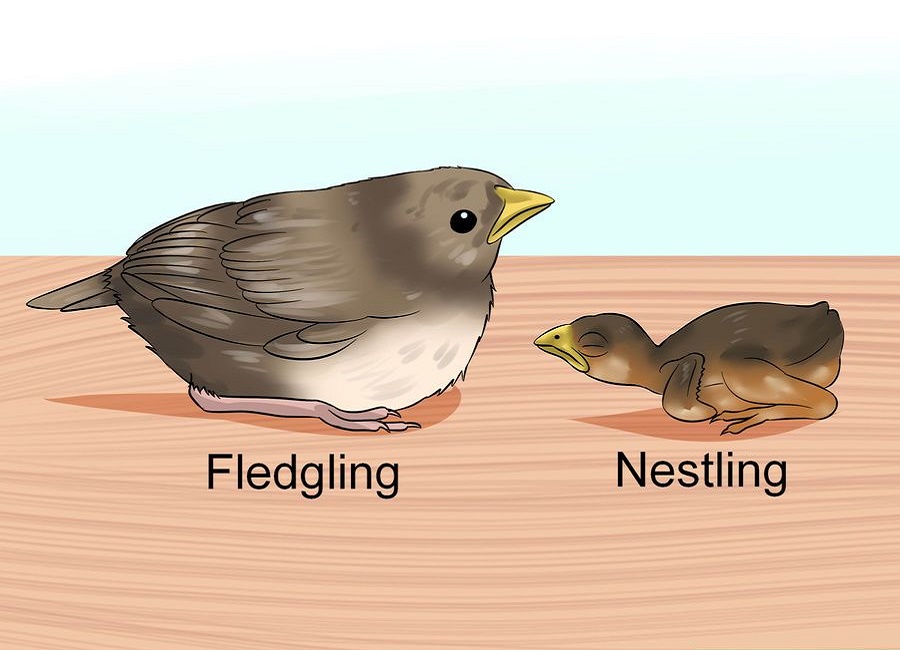

Parrot Growth Stages

There are five development stages of a baby parrot’s growth:

- Neonate (hatchling)

- Nestling

- Fledgling

- Weanling

- Juvenile (pre-adolescent)

Neonate

During the first stage of life, newly-hatched parrots are born with closed eyes. They’re also naked, blind, and deaf, so they depend on their owners.

They’re also naked, blind, and deaf, so they depend on their owners.

In the wild, hatchlings are fed food that their parents regurgitate. Without a mother and father, owners must give chicks a special hand-rearing formula through a syringe.

Nestling

When the parrot reaches the nestling stage, it opens its eyes but remains dependent on its owners.

Imprinting occurs during stage two. When the chick first opens its eyes, it bonds deeply with its parents. If another parrot isn’t present, the baby parrot will imprint on its human owner.

This stage is vital for development, as it needs visual, touch, and sound stimulation.

Fledgling

The fledgling stage is when a parrot begins to learn how to fly.

Some parrots start to lose weight as they’re more preoccupied with flying than eating. As a result, they’re dependent on their owners or parents for food.

Once the parrot has learned how to fly, it’s a good time to clip its wings. However, doing so too early will prevent a parrot from learning to fly.

Wing clipping partially stops a parrot from flying away and protects it from dangers around the house, such as windows, ovens, and ceiling fans.

Weanling

In the weanling stage, parrots consume solid foods independently. Weaning parrots begin to forage and develop skills that allow them to care for themselves.

Juvenile

Parrots become pre-adolescent birds and can fend for themselves. They’ll be on solid food without the need for formula. They’ll be independent of their parents but won’t have reached sexual maturity yet.

At this stage, juvenile parrots won’t have their full adult color. This develops after the molting season, so don’t be alarmed if your baby parrot doesn’t look how you’d expect it to.

The parrot should be at least 8 to 12 weeks old before it’s given a new home.

What Do You Feed Baby Parrots?

Hagen Avicultural Research Institute artificially incubated psittacine eggs, and babies without parents must be hand-fed for 3-5 months.

To do this, mix your chosen hand-rearing formula in boiled water that’s been allowed to cool. Stir all the lumps and bumps to form a smooth, thickened mixture.

When hand-feeding baby parrots, the temperature of the food must be below 45°C before feeding; if the food is under 40°C, there’s a risk of it fermenting and causing infection.

However, most chicks will be cared for by their parents during their initial life stages. Get parrots that have been weaned, as hand-feeding has complications that can compromise the parrot’s health.

Once the parrot has reached the weaning stage, it needs seeds and vegetables. Safe foods include:

- Soaked and sprouted seeds

- Cooked sweet corn kernels

- Soft vegetables

- Fresh fruits

- A selection of greens, including chickweed and dandelion leaves

It takes a while for a baby parrot’s digestive system to become robust enough to cope with dried seeds and pellets. However, leaving a small dish of pellets that parrots can forage through is safe.

Also, ensure a shallow bowl of fresh water is left in its cage.

Baby parrots shouldn’t be fed water orally as they can drown. They receive hydration through regurgitated foods and hand-rear formula, so they only need water bowls once they move onto solid foods when they’re around 4 weeks old.

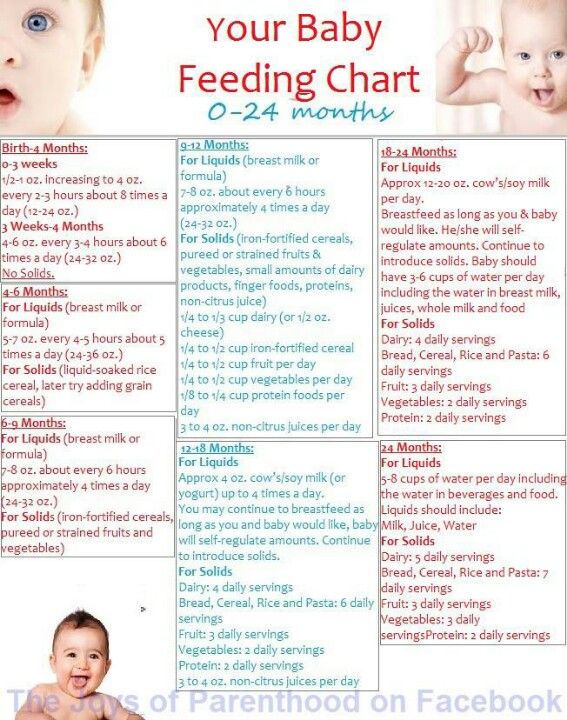

Baby Parrot Feeding Schedule

According to VCA Hospitals, how much and often you feed the baby parrot depends on its age and growth rate. Young birds need regular feeding and eat more often than older birds.

The following guidelines set out how much food the average baby parrot needs. All feeding should be carried out between 6 am and midnight:

- 1-2 weeks: Feed 6-10 times daily, every 2-3 hours.

- 2-3 weeks: Feed 5-6 times daily, every 3-4 hours.

- 3-4 weeks: Feed 4-5 times daily, every 4 hours. The bird can be put into a cage with a low perch and a shallow water bowl at four weeks old.

- 5-6 weeks: Feed twice daily.

Soft seeds, fruits, veggies, and pellets can be put in the cage.

- 7 weeks: Place the bird in a large cage with pellets in cups scattered across the floor.

- 8 weeks: The weaning process should be started. Then, provide nutritionally complete pellets.

After feeding, examine the crop. While the bird has few feathers, you can see when it’s full. However, an examination using the thumb and index finger can also help you check the crop’s fullness.

Healthy parrots should respond well to every feed, and the crop should empty between feedings. They should also produce regular droppings.

How To Keep A Baby Parrot Warm

When a parrot is old enough to live in a cage, the ideal temperature is 65-85 degrees Fahrenheit. Temperatures below 40 degrees are dangerous for birds and can cause health problems.

Similarly, temperatures above 85 degrees cause heat stress, and parrots also need appropriate ventilation to remain cool and comfortable.

However, keeping young chicks warm is more complicated, as even the slightest temperature change can be fatal. However, in the absence of parents, you’ll need to provide the baby parrot warmth to ensure it survives. To do so, follow these steps:

Make A Brooder

You’ll need a container for the parrot to live in. Commercial brooders are expensive, but you can easily make one with a fish tank or plastic container. Opt for metals or plastics that are easy to sanitize.

Choose a brooder that allows the parrot to move about as it grows.

Fill It with Substrate

You’ll need to cover the floor of the container with a substrate. Small parrots do well with folded-up newspaper on the bottom of the brooder, but you can use paper towels.

Avoid wood shavings or cat litter, as curious chicks will try to eat it.

Heat The Brooder

If you’re using a commercial brooder, it’ll already have a thermostatically controlled heating function.

If you’ve made your own, you’ll need to line it with a heat mat. Ensure your chosen heat source has a thermostat so you can amend the temperature.

You can also use a desk lamp set up over the brooder, which uses a red bulb that won’t disturb the chicks. The temperature inside the brooder should be:

- 1-5 days: 96°F

- Days 5-10: 95°F

- From 10 days until they’ve developed some feathers: 91°F

- When they’ve most of their down feathers: 84-89°F

- When the wings and head are mostly covered by feathers: 78-82°F

Once the chick reaches 3 to 4 weeks of age, it can regulate its body temperature.

At this stage, you can remove the heat source. To keep a baby parrot warm, ensure the room the parrot lives in is maintained at the right temperature.

Do Baby Parrots Sleep A Lot?

The majority of parrots are either tropical or subtropical.

They live near the equator, which gets 12 hours of darkness each night. So, parrots are awake from sunrise to sunset and need between 12 to 14 hours of uninterrupted sleep each day.

Baby birds need more than this as they’re growing and developing. Although it’s hard to know how often they’ll sleep, chicks will rest as much as they need to.

It’s not uncommon for baby parrots to only wake up when they’re being fed, sleeping at all other times of the day until they’re older and stronger.

How To Set Up A Parrot Cage

Parrots live in cages from around the age of 7 weeks.

Because they’re still growing, selecting a cage that’ll provide enough room for your parrot to be comfortable when it’s fully grown is important.

Follow these cage setup tips to get started:

Determine the Space of the Bars

Parrots can get their heads stuck or escape from cages with bars set too wide apart. You shouldn’t risk it if you’re out of the house and can’t supervise it constantly.

- Small parrots, like conures, need bars spaced ¾ inch apart.

- Medium-sized birds, like parakeets and cockatiels, need bars spaced ½ inch apart.

- Large parrots, like Amazons and Macaws, need 1 inch between the bars.

Find a cage that allows a parrot to roam freely without too much restriction.

Perches

Parrots are always on their feet, even while sleeping. Therefore, perches are an essential part of the cage’s setup. In the wild, trees and branches provide resting spots of all shapes, sizes, and widths.

Allowing your parrot to adjust its feet to the widths of the perches ensures that it stays supple and flexible, preventing health problems later.

Rope perches can be adapted to fit the cage. Also, add a Pedi perch to the cage so your parrot can keep its claws filed down and its beak under control.

When adding perches to the cage, space them out so the cage doesn’t become crowded. Parrots prefer high perches and tend to ignore all others in the cage.

To start with, place the perches around the mid-level of the cage to allow your parrot to get used to them. Then, move them higher once the parrot has settled and the perches feel familiar.

Food and Water Bowls

Most cages come with at least one food and water tray.

However, with trays that rest on the bottom of the cage, it’s easy for parrots to drop empty seed husks back into it, especially while learning how to forage.

This leads to a risk of starvation, so it’s a good idea to put a couple of upright feeders in the cage. That way, you’ll know that there’s always food available for your parrot.

Position them close to your parrot’s favorite perches so it can easily reach its food.

Substrate

To make your parrot’s cage easier to clean, line the bottom with a layer of substrate. Newspaper will make removing old seed husks and feces easier when it’s time to sanitize the cage.

How To Train A Baby Parrot

The breeder will have done most of the work when it comes to training. However, to get your parrot used to your presence and encourage it to behave appropriately, you’ll need to perform training.

It’ll take time and patience, and training is essential if you want a sociable, tame parrot.

To successfully train a baby parrot, follow these steps:

Start Handling Your Parrot

Your parrot will need to become comfortable with you touching and holding it. It’ll believe it is in charge if you don’t do this right.

Always stand above your parrot so that it knows you’re in control. Then, encourage it to move onto your finger by placing it against its lower breast. You can begin to add commands such as “step up.”

When your parrot does what you want, reward it with a treat to reinforce the message.

Once you become comfortable around each other, practice laddering with your hands, which involves moving your hand to a higher position while encouraging the parrot to step up onto it.

Don’t Overfeed Treats

If you feed your parrot treats too often, it won’t associate them with training. There’s also too much potential for over-feeding, and your bird may reject its regular food.

Discourage Biting

Parrots should never be allowed to bite or behave aggressively. Biting is different from a gentle nibble, in which your parrot will use its tongue to touch your skin.

Also, many parrots use their beaks to balance and may use human hands to coordinate themselves. If your parrot moves toward your hand, don’t assume it’ll bite you, or it may become nervous.

Don’t shout at your bird if you get nipped. Instead, remain calm and say “no” firmly, placing your hand (palm facing forwards) in front of your parrot’s face as a stop gesture.

If your parrot bites you and refuses to let you go, blow on it with a sharp puff of air to make it release. Then, place it back in its cage without a treat.

How To Entertain A Baby Parrot

As parrots spend a significant amount of time in their cage, you must provide entertainment and enrichment to keep your baby parrot mentally and physically healthy. Birds without stimulation can become irritable and destructive.

There’s plenty you can do to keep your parrot occupied, including:

Toys

The first stages of your parrot’s life are crucial to its environmental awareness and development. The bird could grow up with various behavioral problems if it isn’t nurtured.

One of the best ways to combat this is to provide toys such as:

- Puzzles

- Toilet paper for parrots to shred

- Paper sticks

- Chewable objects

- Ladders

- Preening rope

- Bangles

- Building blocks

Putting all toys into the cage at once is impossible, as it’ll cause confusion and take up too much space. Instead, regularly rotate the toys and games to keep your parrot alert and entertained.

Exercises

Let your parrot out of the cage daily for a change of scenery.

Parrots that spend too much time in their cage may become withdrawn and reclusive. Allow them to walk around the house to stretch their legs and wings.

Assign time each day to interact with your baby parrot. This will help you form a bond that the parrot will take through to adulthood.

When your parrot is in its cage, place ladders and other games inside it to encourage your parrot to keep moving, as this will stimulate its mind.

Parrot Playlist

Create a music playlist for your parrot to listen to when you need to leave the house.

Current Biology confirms that parrots can process the sound of music. They also spontaneously move to music, meaning they can dance. A study by Dr. Franck Péron found that Parrots seem to enjoy:

- Pop music

- Rock music

- Folk music

- Classical music

Avoid high-tempo electronic dance music because the same study discovered that parrots subjected to this type of music squawked in distress.

Signs A Baby Parrot Is Sick

Wild parrots avoid showing signs of sickness. Sick birds are the first to be attacked by predators if they sense the parrot is weak and easy to kill. As a result, it’s hard to tell when chicks are unwell.

That said, many symptoms indicate when a parrot is sick:

- Poor feather quality

- Unusually fluffed feathers

- Changes in appetite or eating habits

- Changes to drinking habits; drinking more or less often

- Weakness and lethargy

- Crop not emptying

- Crop not getting full

- Vomiting

- Drooped wings

- Refusal to move

- Increased sleeping

- Inactivity

- Depression

- Bleeding or signs of injury

If you notice one or more of these affecting your baby parrot, take them to an avian vet.

When Can Baby Parrots Leave Their Mother?

In captivity, baby parrots are normally ready to leave their mothers at around 7 to 8 weeks of age. Once a chick hatches, it matures quickly and, once weaned, is ready to leave the nest at around 8 weeks old.

Some breeders prefer to wait until 12 weeks before allowing a baby parrot to go to its new home.

Why Is My Baby Parrot Shaking?

Baby parrots shake and shiver when cold, scared, excited, or sick.

The most common reasons why a baby parrot would shake include the following:

Cold

Baby parrots must be housed in temperatures between 65 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit. The baby parrot will shiver to generate heat if the room is too cold.

A parrot shakes after having a bath. A parrot’s muscles contract involuntarily to generate heat and keep it warm. As soon as the parrot is warm, it’ll stop shivering.

Hot

The parrot will lift and shake its feathers to move cold air around its body to cool itself down. It isn’t technically shivering, but it appears that way.

Scared or Stressed

After moving your baby parrot to its new home, it might shake out of nervousness or stress, especially when it’s away from its mother for the first time.

Birds are sensitive to their environments, and small changes can unsettle them.

When around your new pet, speak gently and move slowly to avoid frightening it further. Work on building your bond but move at your parrot’s pace.

Unwell

Baby parrots hide their sickness, so it’s difficult to determine whether they’re unwell. Parrots can’t tell us when they’re ill and rely on us to pick up on it through their behavior and body language.

My Baby Parrot Is Scared of Me

Understandably, baby parrots take a while to adjust, especially after moving to a new environment.

As prey animals, they’re hard-wired to fear their surroundings until they know you don’t pose a threat. Until that time, they’ll be wary and fearful of you.

Some parrots don’t enjoy being handled and never will. Attempting to win your parrot’s trust by touching it more often is unlikely to help and will only make it more scared when you’re nearby.

However, baby parrots are young enough to adjust to your presence if you follow these steps:

- Don’t make any loud noises.

- Let it live in a quiet, neutral room.

- Don’t handle them too often.

- Keep it away from other pets.

- Don’t disturb them while sleeping.

Over time and with care and attention, your baby parrot should start to trust you, allowing you to begin building a bond with your new pet.

What to feed budgie chicks?

After birth, budgerigars are defenseless, they are completely dependent on their parents. The female feeds and pays attention to each of them, despite the number of offspring and their age difference.

In the beginning, feeding of babies consists of regurgitation by the female of crop milk, which is located in the gizzard. This "milk" is not one substance, it is a yellowish mucus, consisting of very small, almost liquid pieces of food and protein-rich crop milk. A few days after the birth of the chicks, partially digested grain from the goiter is mixed with the "milk". nine0003 Photo: parrots4life

Thanks to sprouted grains in the diet of a lactating female, she produces a sufficient amount of crop milk.

Later, as the parrots mature, the older ones are transferred to grain feed. Since the grain is in the crop, the female feeds the grown chicks first, and when the grain runs out, the crop milk goes to the smallest in the family.

Photo: BikaDuring this period, the male constantly provides the female with everything she needs, as she can leave the nest only in the morning and evening, and even then not always. Sometimes the male helps the female and participates in feeding. He also processes grain feed in the goiter, like the female. Thanks to this, the digestive system of budgerigar chicks works like clockwork, they receive the most nutrients, vital enzymes and boost their immunity. nine0003

Having flown out of the nest for the first time, young parrots most often remain under the care of the male, as the female is going to the second clutch.

The nutritional value of the parents depends on the owners. It is very important to add and exclude certain products in time.

![]()

Feeding a young couple during breeding can be found here.

It happens that breeders have to take on the role of parents of chicks.

Contents

- 1 Reasons for artificial feeding of budgerigar chicks:

- 2 Heating of budgerigar chicks

- 3 There are several options for feeding budgerigars:

- 4 How often to feed budgerigar chicks

Reasons for artificial feeding of budgerigar chicks or failure5: 9003 9003 parents;

- disease of a chick requiring its immediate separation from the feathered family;

- quarantine;

- lack of appetite in the chick, its inability to feed on its own; nine0003

- death or illness of parents;

- a large number of chicks, parents can not cope;

- the female is going to the second clutch and her offspring interferes with her.

The safe period without food for a newly hatched chick is 12 hours.

This is how long a female can go without feeding her baby. And, in case of a non-standard situation, you should count on this period of time to have time to prepare.

You can offer the chick to another pair or offer the male to feed it. Sometimes the bird accepts the baby and thus takes care of him. But it happens that only you can save the situation. nine0003 Photo: ddie gunn

Also, the female is often going to re-lay, her attitude towards the babies may change and you will need to look for additional housing for the young as soon as possible. More often this happens when the chicks are already able to feed on their own, but it happens that the female shows unmotivated aggression early and you need to save the parrots very quickly.

If your chick is only a few days old, then you can only feed with a special factory syringe or a homemade tool. To do this, you will need a 5 ml syringe and a tube that plays the role of a catheter. If you have the smallest chicks, then its diameter should not be more than 2.5 mm and it will be made of strong, soft material without sharp edges. nine0003 Photo: Feeding injector

You should get rid of the syringe, for this you need to glow the cap and carefully remove the needle, drill a little more hole in the nozzle and put on the tube. Wrap the thread tightly around the edge of the tube and nozzle from the syringe. With a factory syringe, you don’t have to suffer like that - everything is provided for in the design.

The catheter must be lowered into the crop to a sufficient depth - if it is not installed correctly, the feed may enter the bird's trachea, which will lead to its death.

Therefore, having decided to breed budgerigars, you should already have a feeding syringe available. nine0003

Baby budgerigar heating

Also, fledglings require additional heating, which you will have to take care of. Devices that breeders use to keep chicks or sick birds warm are called brooders. You can buy them or make your own.

Photo: Magazine about birds The main thing is to be guided by the temperature parameters, since as you grow, the temperature in the room where the parrot is located should decrease.

Chick from a few hours to 4 days - 36 - 36.5°C; 7 days - 34°С; 14 days - 31 - 31.5 ° C; Day 21 - 24°C. Further, the chicks are moved to a box, which is similar in size to a nest box, in such a room the parrots themselves will be able to heat each other. nine0003

If you are raising a single chick, keep it in the brooder until day 25, where you lower the temperature to 24°C. Humidity during this period is maintained at 60%, as during masonry.

There are several options for feeding chicks:

Ready mix. Babies need vitamins and nutrients as well as vital enzymes. Therefore, NutriBird A19, a specialized and balanced food for budgerigar chicks, is just right. The mixture must be diluted not boiled, but heated to 39°C with water. Depending on the age of the chick, you adjust the density of the paste. This is the breeder's most convenient feeding option and one of the best ways to give your chick everything it needs to develop a strong body.

You can buy food for chicks - Padovan Baby Patee Universelle. Some breeders have successfully raised young on it.

Donor bird. Professional breeders use donor birds. Using a catheter, they load a grain mixture into the goiter of a bird, which is later pulled out with a probe. This is an unsafe procedure, so only professionals use this method. The main plus is that the substance that is extracted from the goiter of a parrot is a guarantee that the chick will receive all the vital substances for development. nine0003

Malt milk. A mixture of germinated grains with egg. Malt is prepared from germinated grain, which is crushed and diluted in half with water. Then filter through a strainer and add to the mixture. You should end up with a paste at 39°C.

Medical additive Mezim, Festal, etc. to the porridge. The difficulty lies only in the correct concentration and dilution of these enzymes. It is better to use them together with malt milk.

For power base baby budgerigar, you need to cook baby porridge without milk, sugar and salt: you can boil buckwheat, oatmeal or corn porridge. On the third day of the birth of a chick, you can add vegetable juices to its diet: carrot, beetroot and pumpkin. After the chicks are at least 10 days old, in addition to cereals, you can give a little apple, banana, pomegranate and fat-free cottage cheese.

When the chicks are 20 days old, you can switch them to syringe feeding without catheter or even spoon feeding. From these days, add sprouted grains to the diet (pre-crush into pieces). nine0003

At the age of 30-35 days, the chicks can switch to dry grain, earlier if there is someone nearby who can show them how. But don’t worry, you don’t need to teach this, the chicks successfully begin to taste the grains themselves when the time comes.

How often to feed budgerigar chicks

The smallest chicks should be fed every two hours, at night every 4 hours. Gradually, six feedings with a break for the night are enough for the parrots.

Photo: Dawnstar Australis On the 20th day of life, babies can eat 4 times a day, as they approach 35 days, 3 times will be enough for the chicks. nine0003

Babies start to squeak when they are hungry, and the owners, in addition to the feeding schedule, listen to the sounds coming from the cage.

If your older bird is sick, you may need to feed it more frequently.

It is impossible to overfeed a parrot. Do not let the porridge flow out of the beak.

Try feeding them with a spoon, little by little the chicks will get used to it. If among them the eldest is the first to start eating on his own, there will be a chance that he will become an example for the rest of the parrots. nine0003

Breeding of budgerigars at home

Published: 11/22/2019 Reading time: 11 min. 25621

Share:

When a pair of budgerigars gives birth to chicks, it is an exciting and joyful event for the whole family. However, even before the offspring appear, the owners have to be properly worried, because it is quite difficult to determine the readiness of the birds for reproduction and the pregnancy itself, as well as to understand the features of their incubation of eggs. But everything is not as confusing as it seems: birds live according to certain rules laid down by nature itself, and ordinary observation and basic knowledge are enough to help pets become parents without unnecessary shocks. nine0003

Contents

- Communication of the couple and readiness for reproduction

- Signs of laying readiness in female budgerigars

- Laying, incubation and hatching

- Possible breeding problems

4.1. Masonry alone

4.2. Incorrect egg shape or size

4.3. All eggs in the clutch are empty

4.4. Too frequent clutches - Conclusion nine0152

- installation of the nest box. It will arouse interest in a female ready for offspring, and she will begin to equip it and build a nest from fluffs, twigs and blades of grass that she finds in the cage. Such attention to the house can be one of the sure signals that masonry is just around the corner;

- increase in daylight hours. Long daylight hours can increase the sexual activity of budgerigars, so it is often recommended to increase the illumination using special lamps. However, you can only act gradually: a sharp transition to a long daylight hours can cause premature molting in birds; nine0026

- vitamin and mineral supplements and dietary changes.

Females and males ready for breeding have a sharp increase in appetite, so the daily portions for them are increased. Also included in the daily menu are sources of calcium and vitamin D, including healthy balanced solutions to increase egg production.

- desire for solitude. The female budgerigar becomes less active and sociable: she constantly pushes away her partner, spends more and more time in the nesting house and tirelessly cleans it up; nine0026

- external changes. Abdomen and near-caudal zone in "pregnant" females noticeably increases. Experienced breeders can also gently feel the location of the eggs in the budgie's abdomen before laying;

- large frequency and volume of litter. This is usually one of the signs that laying will begin in the next few hours. At the same time, you can even notice that the tail of a female budgerigar fluctuates in time with breathing. nine0033

Communication of the couple and readiness for reproduction

Sexual maturity in male budgerigars occurs at about 10 months, in females - a little later, after about the first year of life. The owners of an adult pair of birds can count on the appearance of offspring, but only if both the male and the female liked each other. It is easy to notice: the parrot will show off, coo touchingly near his girlfriend and clean her feathers, and his neighbor will favorably accept such signs of attention. If the sympathy of the parrots for each other is obvious, but they obviously do not plan to replenish the pair, you can try to push them to breed. To do this, experienced breeders use the following tricks:

When all favorable conditions for a pair are created, the chances of mating in parrots are very high. You can understand that the birds are ready for breeding by the fluffy plumage and raised tail of the female and the increased activity of the male. The mating season for budgerigars lasts 1-2 weeks with mating 1-2 times a day. During this period, it is extremely important to provide the birds with complete peace, a comfortable microclimate and protection from any stresses and shocks. nine0003

Signs of laying readiness in female budgerigars

The gestation of eggs in parrots can be compared to pregnancy in mammals. Already a few days after the end of the mating period, it can be determined whether the fertilization was successful. You can understand that the female is ready to lay an egg by the following signs:

Laying, incubation and hatching

Masonry. If it was possible to determine that the bird is indeed carrying eggs, it is extremely important to adjust its nutrition. From the menu, females remove foods that can cause diarrhea so that the clutch develops naturally and without unnecessary complications. However, if the expectant mother is in poor health or not feeling well, the veterinarian may recommend special preparations to maintain vitality and the proper formation of chicks. Budgerigars lay eggs approximately 10–18 days after mating. Quantity in one clutch - from 3 to 7 pieces. However, some of them may be infertile. You can determine this by examining each in the light: an embryo with a pattern of blood vessels should be visible in the egg. If nothing shines through inside, such eggs are simply removed from the masonry. nine0003

Incubation. It takes about 3 weeks from the moment of laying until the chicks are born. All this time, the female practically does not leave the nesting house, turns the eggs over for uniform warming and incubation. She can leave the nest only from hunger or thirst, or out of need. All this takes a minimum of time so that the masonry does not have time to cool. At the same time, males also often take care of their girlfriend and their offspring: they bring food and treats to the house, and they can even incubate eggs themselves if the female has gone somewhere. However, it is not uncommon for a female to drop her clutch. Most often this occurs in young parrots during the first "pregnancy", as well as with severe fright or stress. Owners interested in the appearance of offspring in such situations place the eggs in an incubator, inexperienced ones can wait for a new mating season. nine0003

Birth. Budgerigar chicks are born exactly in the order in which the female carried them, so there can be both chicks and eggs in the house at the same time. Then the mother and father take care of them for 1–2 months: the female feeds them with goiter milk and warms them under the wings, and the male looks after them during those short periods when she is absent. By the end of the 2nd month, the babies leave the nest and get out into the cage on their own. Immediately after this, it is necessary to remove the house so that it does not cause the couple to breed again: for the full development of the next offspring, the mother needs to rest for at least a few months. nine0003

Possible reproduction problems

The reproductive system of budgerigars is quite fragile and sensitive, even minor disruptions in the body can affect it. In the event of any such problems, the owner needs to pay maximum attention to the pet, and the advice of a veterinarian and the right treatment become vital. Below is a list of the most common egg laying problems for females.

Masonry alone

If a female budgerigar nests and lays alone, then we can talk about a certain pathology in the bird's body. However, rare masonry will have little effect on the health of the pet, but if this happens often, there is a risk that she will suffer from a serious lack of calcium in the body. Of course, no one hatches from unfertilized eggs.

Incorrect egg shape or size

With nutritional problems and a lack of nutrients - primarily calcium - the egg is formed with a defect in shape. Because of this, it cannot properly exit the female's oviduct, compresses the nerves and surrounding organs, which in some cases leads to the death of the bird. You can notice such a complication by heavy breathing and a noticeable tension in the abdomen of the parrot, as well as limping, when the paws become numb due to long attempts to lay the egg. nine0003

All eggs in clutch are empty

When a pair nests safely and the female lays clutch after clutch, but all the eggs in it are without embryos, then this can be either a genetic feature or a consequence of infectious diseases. In this case, the parrots are separated so that the female does not waste health and strength and does not suffer from exhaustion.

Too frequent clutches

Parrots may be ready for a new mating season almost as soon as the old offspring have left the nest. This should not be allowed, because the female does not have time to recover and rest, she becomes very weak and experiences stress that can lead to rupture of the oviduct and the egg getting stuck in the abdominal cavity. You can determine the gap by a sharp weight loss of the parrot with an abnormal increase in the abdomen and by a pose with widely spread legs.