Baby getting breast feed

Breastfeeding FAQs: How Much and How Often (for Parents)

Breastfeeding is a natural thing to do, but it still comes with its fair share of questions. Here's what you need to know about how often and how long to breastfeed your baby.

How Often Should I Breastfeed?

Newborn babies should breastfeed 8–12 times per day for about the first month. Breast milk is easily digested, so newborns are hungry often. Frequent feedings helps stimulate your milk production during the first few weeks.

By the time your baby is 1–2 months old, he or she probably will nurse 7–9 times a day.

In the first few weeks of life, breastfeeding should be "on demand" (when your baby is hungry), which is about every 1-1/2 to 3 hours. As newborns get older, they'll nurse less often, and may have a more predictable schedule. Some might feed every 90 minutes, whereas others might go 2–3 hours between feedings.

Newborns should not go more than about 4 hours without feeding, even overnight.

How Do I Count the Time Between Feedings?

Count the length of time between feedings from the time your baby begins to nurse (rather than at the end) to when your little one starts nursing again. In other words, when your doctor asks how often your baby is feeding, you can say "about every 2 hours" if your first feeding started at 6 a.m., the next feeding was around 8 a.m., then 10 a.m., and so on.

Especially at first, you might feel like you're nursing around the clock, which is normal. Soon enough, your baby will go longer between feedings.

How Long Does Nursing Take?

Newborns may nurse for up to 20 minutes or longer on one or both breasts. As babies get older and more skilled at breastfeeding, they may take about 5–10 minutes on each side.

How long it takes to breastfeed depends on you, your baby, and other things, such as whether:

- your milk supply has come in (this usually happens 2–5 days after birth)

- your let-down reflex (which causes milk to flow from the nipple) happens right away or after a few minutes into a feeding

- your milk flow is slow or fast

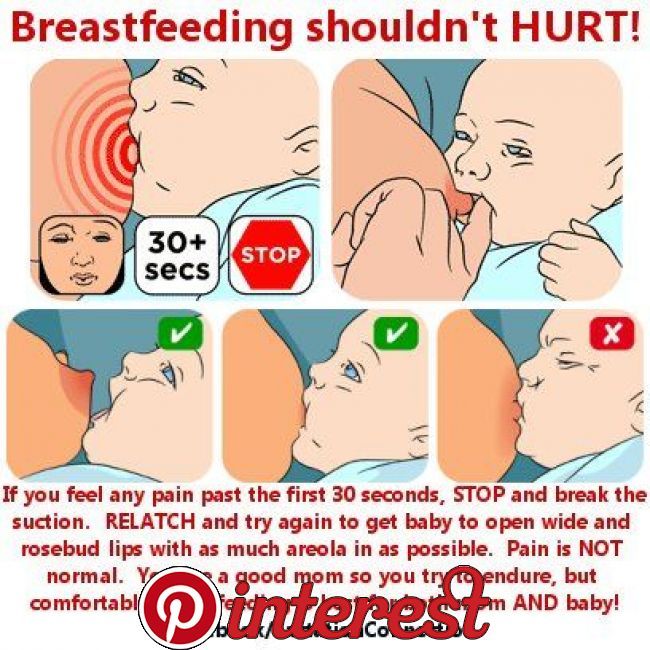

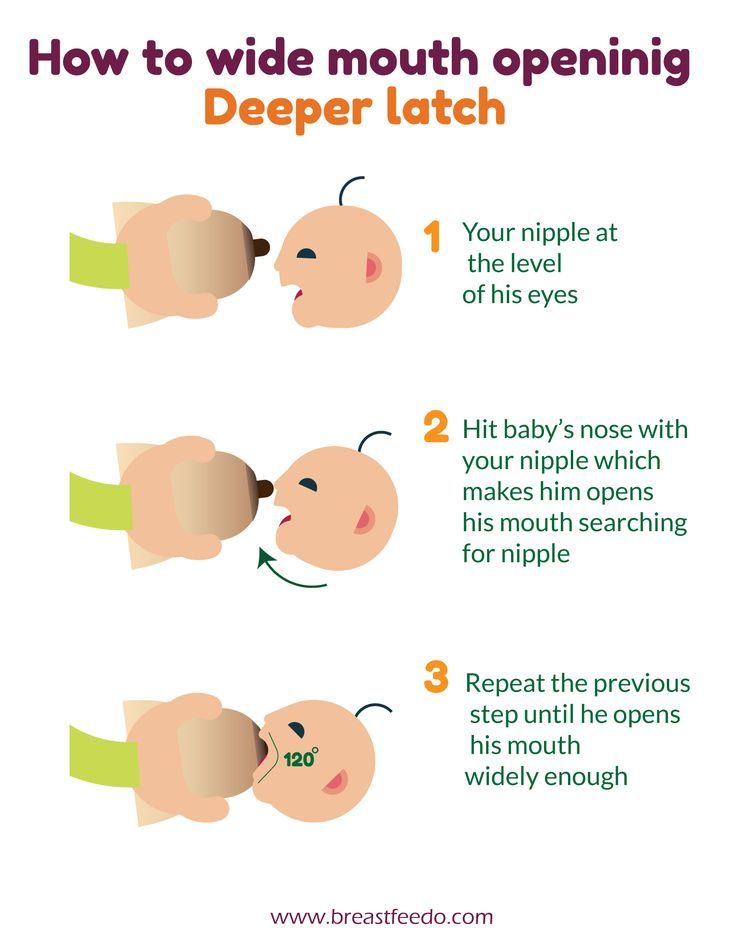

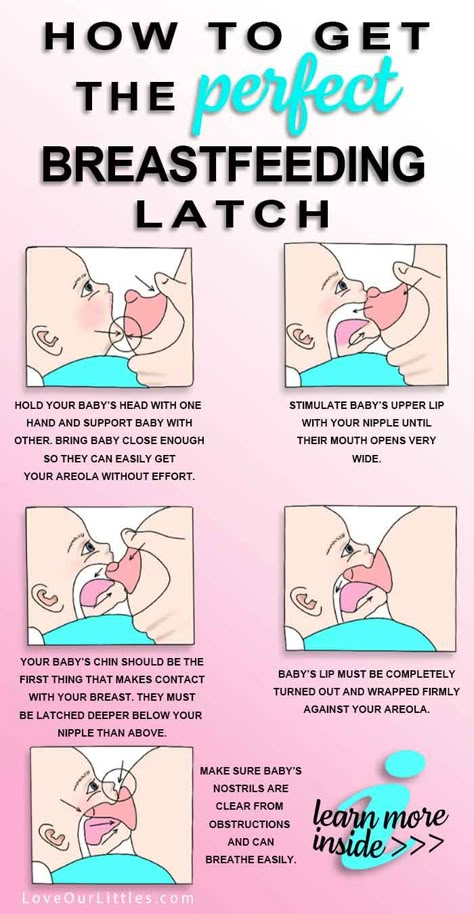

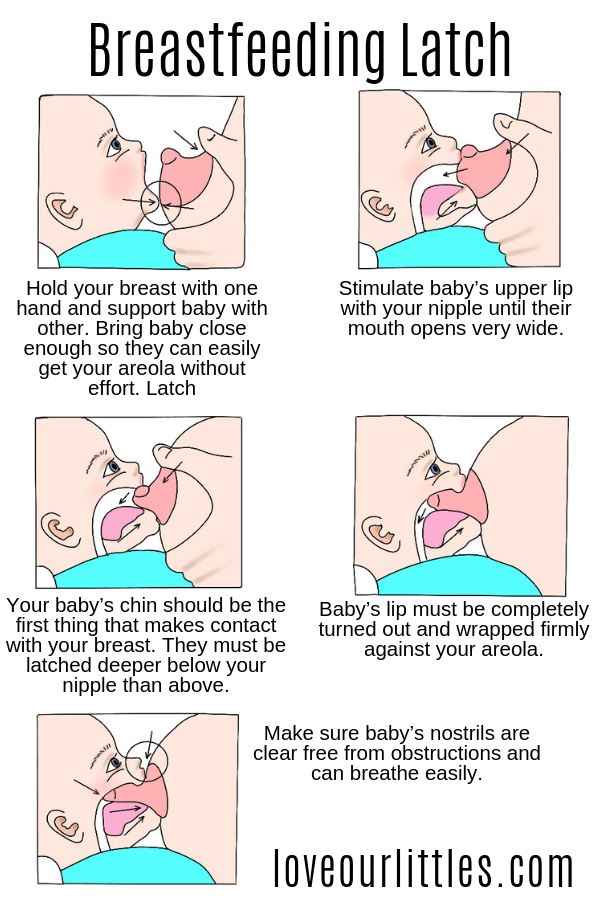

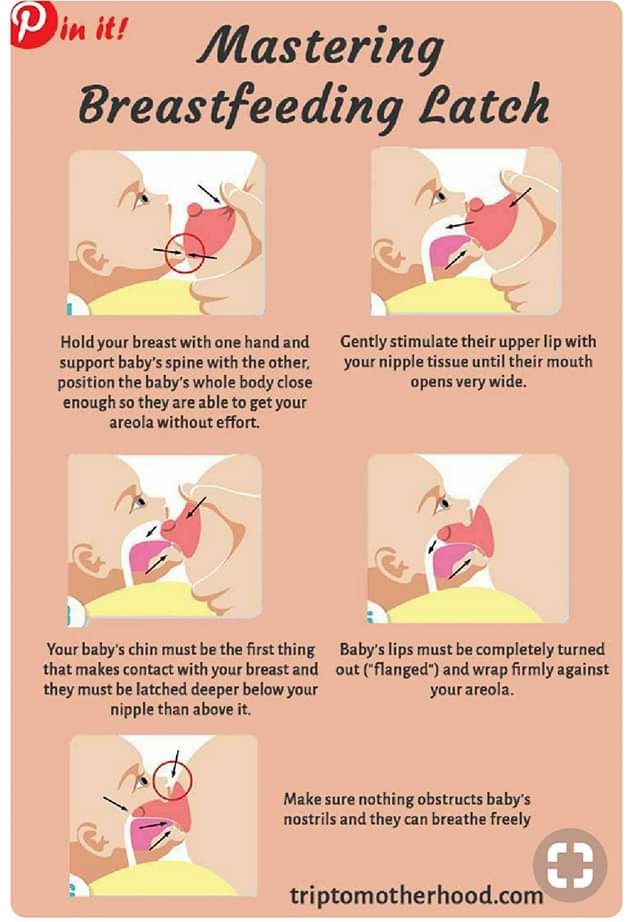

- the baby has a good latch, taking in as much as possible of your areola (the dark circle of skin around your nipple)

- your baby begins gulping right away or takes it slow

- your baby is sleepy or distracted

Call your doctor if you're worried that your baby's feedings seem too short or too long.

When Should I Alternate Breasts?

Alternate breasts and try to give each one the same amount of nursing time throughout the day. This helps to keep up your milk supply in both breasts and prevents painful engorgement (when your breasts overfill with milk).

You may switch breasts in the middle of each feeding and then alternate which breast you offer first for each feeding. Can't remember where your baby last nursed? It can help to attach a reminder — like a safety pin or small ribbon — to your bra strap so you'll know which breast your baby last nursed on. Then, start with that breast at the next feeding. Or, keep a notebook handy or use a breastfeeding app to keep track of how your baby feeds.

Your baby may like switching breasts at each feeding or prefer to nurse just on one side. If so, then offer the other breast at the next feeding. Do whatever works best and is the most comfortable for you and your baby.

How Often Should I Burp My Baby During Feedings?

After your baby finishes on one side, try burping before switching breasts. Sometimes, the movement alone can be enough to cause a baby to burp.

Sometimes, the movement alone can be enough to cause a baby to burp.

Some infants need more burping, others less, and it can vary from feeding to feeding.

If your baby spits up a lot, try burping more often. While it's normal for infants to "spit up" a small amount after eating or during burping, a baby should not vomit after feeding. If your baby throws up all or most of a feeding, there could be a problem that needs medical care. If you're worried that your baby is spitting up too much, call your doctor.

Why Is My Baby Hungrier Than Usual?

When babies go through a period of rapid growth (called a growth spurt), they want to eat more than usual. These can happen at any time. But in the early months, growth spurts often happen when a baby is:

- 7–14 days old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

During these times and whenever your baby seems extra hungry, follow your little one's hunger cues. You may need to breastfeed more often for a while.

How Long Should I Breastfeed My Baby?

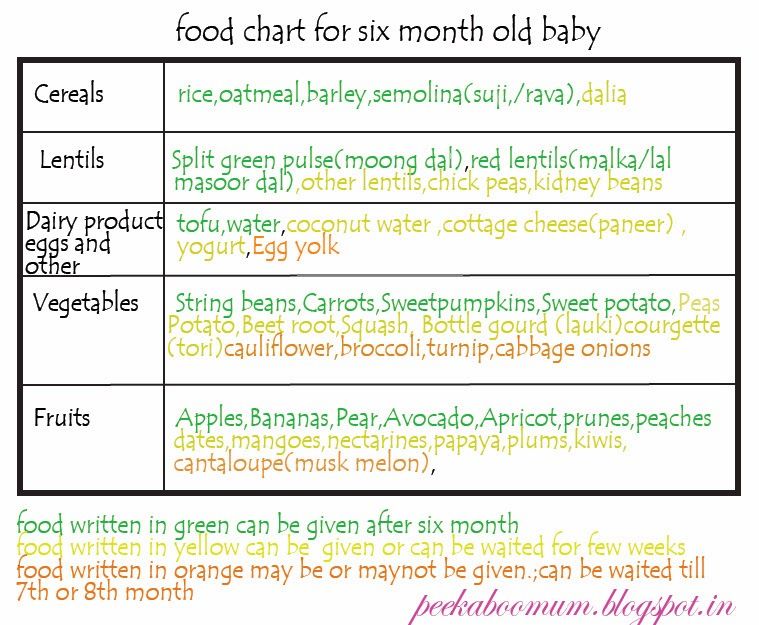

That's a personal choice. Experts recommend that babies be breastfed exclusively (without formula, water, juice, non–breast milk, or food) for the first 6 months. Then, breastfeeding can continue until 12 months (and beyond) if it's working for you and your baby.

Breastfeeding has many benefits for mom and baby both. Studies show that breastfeeding can lessen a baby's chances of diarrhea, ear infections, and bacterial meningitis, or make symptoms less severe. Breastfeeding also may protect children from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), diabetes, obesity, and asthma.

For moms, breastfeeding burns calories and helps shrink the uterus. In fact, breastfeeding moms might return to their pre–pregnancy shape and weight quicker. Breastfeeding also helps lower a woman's risk of diseases like:

- breast cancer

- high blood pressure

- diabetes

- heart disease

It also might help protect moms from uterine cancer and ovarian cancer.

Breastfeeding: is my baby getting enough milk?

When you first start breastfeeding, you may wonder if your baby is getting enough milk.

It may take a little while before you feel confident your baby is getting what they need.

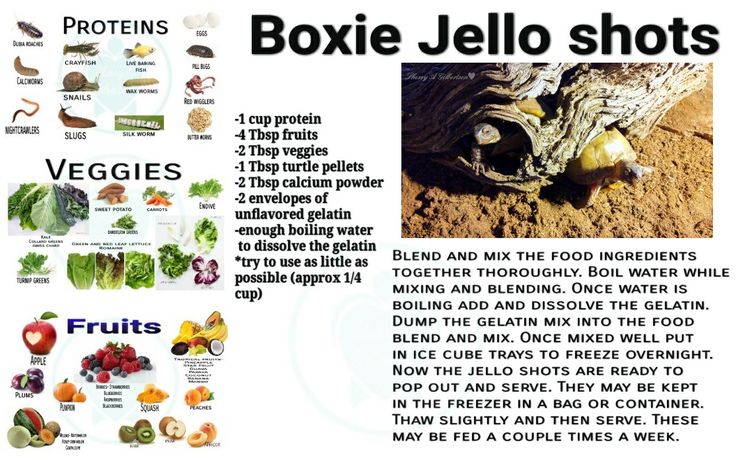

Exclusive breastfeeding (breast milk only) is recommended for around the first 6 months of your baby's life. Introducing bottle feeds will reduce the amount of breast milk you produce.

Read Unicef's checklist How can I tell if breastfeeding is going well? for more guidance.

Credit:

IAN BODDY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/294115/view

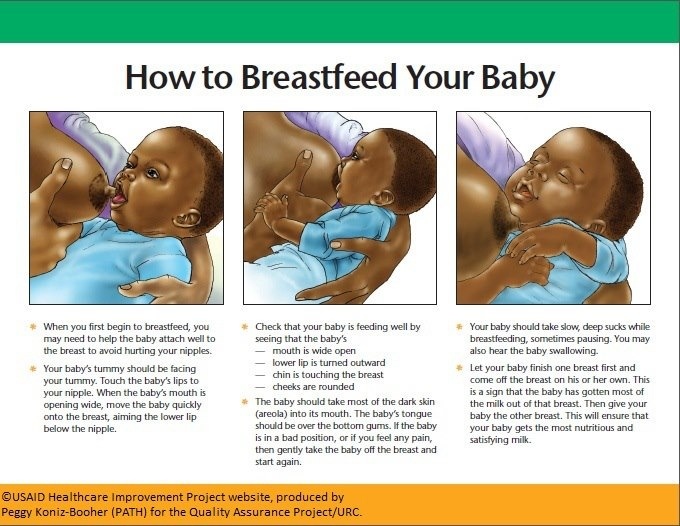

Signs your baby is well attached

- Your baby has a wide mouth and a large mouthful of breast.

- Your baby's chin is touching your breast, their lower lip is rolled down (you can't always see this) and their nose isn't squashed against your breast.

- You don't feel any pain in your breasts or nipples when your baby is feeding, although the first few sucks may feel strong.

- You can see more of the dark skin around your nipple (areola) above your baby's top lip than below their bottom lip.

Signs your baby is getting enough milk

- Your baby starts feeds with a few rapid sucks followed by long, rhythmic sucks and swallows with occasional pauses.

- You can hear and see your baby swallowing.

- Your baby's cheeks stay rounded, not hollow, during sucking.

- They seem calm and relaxed during feeds.

- Your baby comes off the breast on their own at the end of feeds.

- Their mouth looks moist after feeds.

- Your baby appears content and satisfied after most feeds.

- Your breasts feel softer after feeds.

- Your nipple looks more or less the same after feeds – not flattened, pinched or white.

- You may feel sleepy and relaxed after feeds.

Other signs your baby is feeding well

- Your baby gains weight steadily after the first 2 weeks – it's normal for babies to lose some of their birth weight in the first 2 weeks.

- They appear healthy and alert when they're awake.

- From the fourth day, they should do at least 2 soft, yellow poos the size of a £2 coin every day for the first few weeks.

- From day 5 onwards, wet nappies should start to become more frequent, with at least 6 heavy, wet nappies every 24 hours.

In the first 48 hours, your baby is likely to have only 2 or 3 wet nappies.

In the first 48 hours, your baby is likely to have only 2 or 3 wet nappies.

It can be hard to tell if disposable nappies are wet. To get an idea, take an unused nappy and add 2 to 4 tablespoons of water. This will give you an idea of what to look and feel for.

Ways to boost your breast milk supply

- Ask your midwife, health visitor or breastfeeding specialist to watch your baby feeding. They can offer guidance and support to help you properly position and attach your baby to the breast.

- Avoid giving your baby bottles of formula for the first 6 months or a dummy until breastfeeding is well established.

- Feed your baby as often as they want and for as long as they want.

- Expressing some breast milk after feeds once breastfeeding is established will help build up your supply.

- Offer both breasts at each feed and alternate which breast you start with.

- Keep your baby close to you and hold them skin to skin. This will help you spot signs your baby is ready to feed early on, before they start crying.

Things that can affect your milk supply

- Poor attachment and positioning.

- Not feeding your baby often enough.

- Drinking alcohol and smoking while breastfeeding – these can both interfere with your milk production.

- Previous breast surgery, particularly if your nipples have been moved.

- Having to spend time away from your baby after the birth – for example, because they were premature.

- Illness in you or your baby.

- Giving your baby bottles of formula or a dummy before breastfeeding is well established.

- Using nipple shields – although this may be the only way to feed your baby with damaged nipples and is preferable to stopping feeding.

- Some medicines, including dopamine, ergotamine and pyridoxine. Read more about breastfeeding and medicines.

- Anxiety, stress or depression.

- Your baby having a tongue tie that restricts the movement of their tongue.

With skilled help, lots of these problems can be sorted out. If you have concerns about how much milk your baby is getting, it's important to ask for help early.

Speak to your midwife, health visitor or a breastfeeding specialist. They can also tell you where you can get further support.

Got a breastfeeding question?

For fast, friendly, trusted NHS advice anytime, day or night, talk to the Start4Life Breastfeeding Friend on Amazon Alexa, Facebook Messenger or Google Home.

Video: Is my baby getting enough milk?

In this video, a health visitor talks about the signs your baby is getting enough milk.

Media last reviewed: 1 November 2019

Media review due: 1 November 2022

Page last reviewed: 6 September 2022

Next review due: 6 September 2025

Benefits of breastfeeding for baby

1 Victora CG et al . Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect . Lancet . 2016;387(10017):475-490. - Victor S.J. et al., "Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms and long-term effects". Lancet (Lancet). 2016;387(10017):475-490.

2 Bode L It’s alive: microbes and cells in human milk and their potential benefits to mother and infant . Adv Nutr . 2014;5(5):571-573. "It's Alive: Breastmilk Microbes and Cells and Their Potential Benefits for Mother and Baby. " Adv Nutr. 2014;5(5):571-573.

" Adv Nutr. 2014;5(5):571-573.

3 Ballard O Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors . Pediatr Clin North Am . 2013;60(1):49-74. - Ballard O., Morrow A.L., "Composition of breast milk: nutrients and biologically active factors." Pediatrician Clean North Am. 2013;60(1):49-74.

4 Ladomenou F Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child . 2010; 95(12):1004-1008. - Ladomenu, F. et al., "The effect of exclusive breastfeeding on infection protection in infancy: a prospective study." Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(12):1004-1008.

5 Vennemann MM et al. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics. 2009;123(3): e 406-410. - Wennemann M.M. et al., "Does Breastfeeding Reduce the Risk of Sudden Infant Death?" Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2009;123(3):e406-e410.

2009;123(3): e 406-410. - Wennemann M.M. et al., "Does Breastfeeding Reduce the Risk of Sudden Infant Death?" Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2009;123(3):e406-e410.

6 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clinic Transl Immunology . 2013;2(4): e 3. - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

7 Harrison D et al. Breastfeeding for procedural pain in infants beyond the neonatal period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2016;10: CD 011248. - Harrison D. et al., "Breastfeeding for Relief of Medical Pain in the Neonatal Period." Cochrane Database of System Rev. 2014; 10: CD 11248

2014; 10: CD 11248

8 JOHNSON TJ et AL . Economic benefits and costs of human milk feedings: a strategy to reduce the risk of prematurity-related morbidities in very-low-birth-weight infants. Adv Nutr . 2014;5(2):207-212. — Johnson T.J. et al., Economic Benefits and Costs of Breastfeeding: A Strategy for Reducing the Risk of Preterm Complications in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Adv. 2014;5(2):207-212.

9 Schanler RJ et al. Randomized trial of donor human milk versus preterm formula as substitutes for mothers' own milk in the feeding of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics . 2005;116(2):400-406. - Chanler R.J. et al., "Randomized Trial of Donor Human Milk Versus Prematurity Formula as a Breast Milk Substitute in Severely Preterm Infants". Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2005;116(2):400-406.

2005;116(2):400-406.

10 Brown A, Harries V. Infant sleep and night feeding patterns during later infancy: association with breastfeeding frequency, daytime complementary food intake, and infant weight. Breastfeed Med . 2015;10(5):246-252. - Brown A., Harris W., "Night feedings and infant sleep in the first year of life and their association with feeding frequency, daytime supplementation, and infant weight." Brest Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2015;10(5):246-252.

11 Sánchez CL et al. The possible role of human milk nucleotides as sleep inducers. Nutr Neurosci . 2009;12(1):2-8. - Sanchez S.L. et al., "Nucleotides in breast milk may help the baby fall asleep." Nutr Neurosai. 2009;12(1):2-8.

12 Dekaban AS. Changes in brain weights during the span of human life: relation of brain weights to body heights and body weights. Ann Neurol . 1978 4(4):345-356. - Dekaban A.S., "Change in the weight of the human brain throughout life: the relationship of brain weight with height and body weight." Ann Neirol. 1978 4(4):345-356.

Ann Neurol . 1978 4(4):345-356. - Dekaban A.S., "Change in the weight of the human brain throughout life: the relationship of brain weight with height and body weight." Ann Neirol. 1978 4(4):345-356.

13 Deoni SC et al. Breastfeeding and early white matter development: A cross-sectional study. Neuroimage . 2013;82:77-86. - Deoni S.S. et al., Breastfeeding and early white matter development: a cross-sectional study. Neuroimaging. 2013;82:77-86.

14 Straub N et al. Economic impact of breast-feeding-associated improvements of childhood cognitive development, based on data from the ALSPAC. Br J Nutr . 2016:1-6. - Straub N. et al., "Economic Impact of Breastfeeding-Associated Cognitive Development in the Child (According to ALSPAC )". Br J Nutr. 2016;1-6.

15 Victora CG et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health . 2015; 3(4): e 199-205. - Victor S.J. and co-authors, "Relationship between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment and income level at age 30: a prospective cohort study in Brazil." Lancet Globe Health. 2015; 3(4):e199-205.

Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health . 2015; 3(4): e 199-205. - Victor S.J. and co-authors, "Relationship between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment and income level at age 30: a prospective cohort study in Brazil." Lancet Globe Health. 2015; 3(4):e199-205.

16 Horta BL, Victora CG. Breastfeeding and adult intelligence – Authors’ reply. Lancet Glob Health . 2015;3(9): e 522. - Horta B.L., Victora S.J., "Breastfeeding and intelligence in adulthood - Author's response". Lancet Globe Health. 2015;3(9):e522.

17 Belkind-Gerson J et al. Fatty acids and neurodevelopment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47 Suppl 1:7-9 - Belkind-Gerson, J. et al., "Fatty acids and brain development." J Pediatrician Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47 Appendix 1:7-9

2008;47 Suppl 1:7-9 - Belkind-Gerson, J. et al., "Fatty acids and brain development." J Pediatrician Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47 Appendix 1:7-9

18 Heikkilä K et al. Breast feeding and child behavior in the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child . 2011;96(7):635-642. - Heikkila K. et al., Breastfeeding and Child Behavior in a Millennial Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):635-642.

19 Tharner A et al. Breastfeeding and its relation to maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2012;33(5):396-404. — Tarner, A. et al., "Breastfeeding and its relation to maternal sensitivity and infant attachment." J Dev Behave Pediatrician. 2012;33(5):396-404.

20 Montgomery SM et al. Breast feeding and resilience against psychosocial stress. Arch Dis Child . 2006;91(12):990-994. - Montgomery S.M. et al., Breastfeeding and resilience to psychosocial stress. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(12):990-994.

Arch Dis Child . 2006;91(12):990-994. - Montgomery S.M. et al., Breastfeeding and resilience to psychosocial stress. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(12):990-994.

21 Bener A et al. Does continued breastfeeding reduce the risk for childhood leukemia and lymphomas? Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60(2):155-161. - Bener A. et al., "Does long-term breastfeeding reduce the risk of leukemia and lymphoma in a child?". Minerva Pediatrician. 2008;60(2):155-161.

22 Singhal A et al. Infant nutrition and stereoacuity at age 4-6 y. Am J Clin Nutr . 2007;85(1):152-159. - Singhal A. et al., Nutrition in infancy and stereoscopic visual acuity at 4-6 years of age. Am F Clean Nutr. 2007;85(1):152-159.

23 Peres KG et al. Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr . 2015;104(467):54-61. - Perez K.G. et al., "The impact of breastfeeding on malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):54-61.

Acta Paediatr . 2015;104(467):54-61. - Perez K.G. et al., "The impact of breastfeeding on malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):54-61.

24 Horta BL et al. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr . 2015; 104(467):30-37 - Horta B.L. et al., "Long-term effects of breastfeeding and their impact on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

25 Lund-Blix NA et al. Infant feeding in relation to islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible children: the MIDIA Study. Diabetes Care . 2015;38(2):257-263. - Lund-Blix N.A. et al., "Breastfeeding in the context of isolated autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in genetically predisposed children: the MIDIA study ". Diabitis Care. 2015;38(2):257-263.

Diabitis Care. 2015;38(2):257-263.

The benefits of breastfeeding | Medela

1 World Health Organization. Health topics: Breastfeeding [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018 [Accessed: 03/26/2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/en/ - World Health Organization. "Health Matters: Breastfeeding" [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018 [Visit 03/26/2018]. Article at: http://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/en/

2 Innocenti Research Centre. 1990–2005 Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding: past achievements, present challenges and the way forward for infant and young child feeding. Florence : United Nations 2005. 38 p . - Innocenti Research Centre, "1990-2005: Anniversary of the Innocenti Declaration to Protect, Promote and Support Breastfeeding. Achievements, new challenges, the path to successful infant and young child feeding. " Florence: United Nations Children's Fund; 2005. Pp. 38.

" Florence: United Nations Children's Fund; 2005. Pp. 38.

3 Dettwyler KA. When to wean: biological versus cultural perspectives.Clin Obstet Gyecol. 2004;47(3):712-723. — K. A. Dettwiler, "A Time to Wean: Weaning from a Biological and Cultural Perspective." Klin Obstet Ginekol (Clinical obstetrics and gynecology). 2004;47(3):712-723.

4 1.000 Days . [ Internet ] Washington DC , USA ; 2018. Available from : https://thousanddays.org - "Thousand Days" [Internet] Washington DC, USA; 2018. Article at link: https://thousanddays.org

5 TED. TEDWomen: What we don't know about mother's milk [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: TED Conferences LLC; 2016. [Accessed 03/26/2018]. Available from www. ted.com/talks/katie_hinde_what_we_don_t_know_about_mother_s_milk/reading-list - TED. "TED Women: What We Don't Know About Breast Milk" [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: TED Conference LLS; 2016. [Visit 03/26/2018]. The talk is available at: www.ted.com/talks/katie_hinde_what_we_don_t_know_about_mother_s_milk/reading-list

ted.com/talks/katie_hinde_what_we_don_t_know_about_mother_s_milk/reading-list - TED. "TED Women: What We Don't Know About Breast Milk" [Internet]. New York, NY, USA: TED Conference LLS; 2016. [Visit 03/26/2018]. The talk is available at: www.ted.com/talks/katie_hinde_what_we_don_t_know_about_mother_s_milk/reading-list

6 Kent JC et al. Breast volume and milk production during extended lactation in women. Exp Physiol. 1999;84(2):435-447. - Kent J.S. et al., "Amount and production of breast milk during long-term lactation in women". Ex Physiol. 1999;84(2):435-447.

7 Kuo AA et al. Introduction of solid food to young infants. Matern Child Health J . 2011;15(8):1185-1194. - Kuo A.A. et al., "Introduction of Solid Complementary Foods to Young Children". Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(8):1185-1194.

8 Dewey, KG. Nutrition, growth, and complementary feeding of the breastfed infant. Pediatric Clin North Am . 2001;48(1):87-104. - Dewey, CJ, "Nutrition, Growth, and Complementary Feeding for the Breastfed Child." Pediatrician Clean North Am. 2001;48(1):87-104.

9 Bener A et al. Does continued breastfeeding reduce the risk for childhood leukemia and lymphomas? Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60(2):155-161. - Bener A. et al., "Does long-term breastfeeding reduce the risk of leukemia and lymphoma in a child?". Minerva Pediatric. 2008;60(2):155-161.

10 Poudel RR, Shrestha D. Breastfeeding for diabetes prevention.JPMA. J Pak Med Assoc . 2016;66(9 Suppl 1): S 88-90. - Poodle R.R., Shrestha D. , "Breastfeeding as a way to prevent diabetes." JPMA. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(9 Suppl 1):S88-90.

, "Breastfeeding as a way to prevent diabetes." JPMA. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(9 Suppl 1):S88-90.

11 Singhal A et al. Infant nutrition and stereoacuity at age 4–6 y. Am J Clin Nutr . 2007;85(1):152-159. - Singhal A. et al., Nutrition in infancy and stereoscopic visual acuity at 4-6 years of age. Am F Clean Nutr. 2007;85(1):152-159.

12 Peres KG et al. Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104( S 467):54-61. - Perez K.G. et al., "The effect of breastfeeding on malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):54-61.

13 Horta BL et al. Long - term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104( S 467):30-37. Horta B.L. et al., "Long-term effects of breastfeeding and their impact on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

Acta Paediatr. 2015;104( S 467):30-37. Horta B.L. et al., "Long-term effects of breastfeeding and their impact on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

14 Howie PW et al. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. BMJ . 1990;300(6716):11-16. — Howie PW, "Breastfeeding as a defense against infectious diseases." BMJ. 1990;300(6716):11-16.

15 Ladomenou F et al. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch DisChild. 2010;95(12):1004-1008. - Ladomenu, F. et al., "The effect of exclusive breastfeeding on infection protection in infancy: a prospective study." Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(12):1004-1008.

16 Sankar MJ et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Acta paediatr. 2015;104( S 467):3-13. - Sankar M.J. and co-authors, "Optimal Breastfeeding Practices and Mortality in Infants and Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Pediatric act. 2015;104(S467):3-13.

Acta paediatr. 2015;104( S 467):3-13. - Sankar M.J. and co-authors, "Optimal Breastfeeding Practices and Mortality in Infants and Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Pediatric act. 2015;104(S467):3-13.

17 Lönnerdal B. Bioactive proteins in breast milk. J Pediatric Child Health. 2013;49( S 1):1-7. - Lönnerdahl B., "Biologically active proteins of breast milk". F Pediatrician Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7.

18 Gridneva Z et al. Effect of human milk appetite hormones, macronutrients, and infant characteristics on gastric emptying and breastfeeding patterns of term fully breastfed infants. Nutrients. 2016;9(1):15. - Gridneva Z. et al., "Influence of Appetite Hormones and Macronutrients of Breast Milk and Their Relationship with Infant Gastric Evacuation and Feeding Behavior in an Exclusively Breastfed Full-Term Infant. " Nutrients. 2016;9(1):15.

" Nutrients. 2016;9(1):15.

19 Field CJ. The immunological components of human milk and their effect on immune development in infants. J Nutr . 2005;135(1):1-4. - Field S.J., "Immune components of breast milk and their influence on the development of the child's immune system." F Int. 2005;135(1):1-4.

20 Hassiotou F, Hartmann PE. At the dawn of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells. Adv Nutr . 2014;5(6):770-778. - Hassiot F, Hartmann PI, "On the threshold of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells." Adv. 2014;5(6):770-778.

21 Cregan MD et al. Identification of nestin-positive putative mammary stem cells in human breastmilk. Cell Tissue Res . 2007;329(1):129-136. - Cregan M.D. et al., "Search for nestin-positive stem cells in human breast milk". Cell Tissue Res. 2007;329(1):129-136.

Cell Tissue Res. 2007;329(1):129-136.

22 Victora CG et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475-490. - Victor S.J. et al., "Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms and long-term effects". Lancet (Lancet). 2016;387(10017):475-490.

23 Heikkilä K et al. Breast feeding and child behavior in the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch DisChild. 2011;96(7):635-642. - Heikkila K. et al., Breastfeeding and Child Behavior in a Millennial Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):635-642.

24 Oddy WH et al. The long-term effects of breastfeeding on child and adolescent mental health: a pregnancy cohort study followed for 14 years. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):568-574. — Oddie W.H. et al., "Long-term impact of breastfeeding on cognitive development in children and adolescents: a cohort study from pregnancy through 14 years. " F Pediatrician (Journal of Pediatrics). 2010;156(4):568-574.

" F Pediatrician (Journal of Pediatrics). 2010;156(4):568-574.

25 Ballard O, Morrow AL. Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2013;60(1):49-74. - Ballard O., Morrow A.L., "Composition of breast milk: nutrients and biologically active factors." Pediatrician Clean North Am. 2013;60(1):49-74.

26 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clin Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4): e 3. - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

27 Peters SA et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of maternal cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of 300,000 Chinese women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6): e 006081. - Peters S.A. et al., "Breastfeeding and Maternal Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Study of 300,000 Chinese Women". J Am Hart Assoc. 2017;6(6):e006081.

J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6): e 006081. - Peters S.A. et al., "Breastfeeding and Maternal Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Study of 300,000 Chinese Women". J Am Hart Assoc. 2017;6(6):e006081.

28 Horta BL et al. Long - term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104( S 467):30-37. - Horta B.L. et al., "Long-term effects of breastfeeding and their impact on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

29 Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50 302 women with breast cancer and 96,973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9328):187-195. - The Breast Cancer Hormonal Factor Collaborative Group, "Breast Cancer and Breastfeeding: A joint reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries involving 50,302 women with breast cancer and 96,973 healthy women." Lancet (Lancet). 2002;360(9328):187-195.

Lancet. 2002;360(9328):187-195. - The Breast Cancer Hormonal Factor Collaborative Group, "Breast Cancer and Breastfeeding: A joint reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries involving 50,302 women with breast cancer and 96,973 healthy women." Lancet (Lancet). 2002;360(9328):187-195.

30 Li DP et al. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies. Asian 9 Cancer Prev . 2014;15(12):4829-4837. - Lee D.P. et al., "Breastfeeding and the risk of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies." Asia Pas W Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4829-4837.

31 Jordan SJ et al. Breastfeeding and endometrial cancer risk: an analysis from the epidemiology of endometrial cancer consortium.Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(6):1059-1067. — Jordan S.

/imgs/2020/05/29/12/3933015/7cf142452ac7f89551afc432db0e634f8b6b47e5.jpg)