Breastfeeding and baby food

Working Together: Breastfeeding and Solid Foods

Breastfeeding, like many other aspects of parenting, is a gradual process of increasing independence and self-mastery on your baby’s part and a gradual stepping back on yours. You may have already experienced the beginnings of this process during the first half year of life as your baby learned to enjoy drinking expressed breast milk from a bottle or cup and you began to go places without her. Still, the two of you were closely tied to each other in a nutritional sense: your child thrived on your breast milk alone, which provided the nutrients she needed.

During the second half of the year, your breast milk will continue to provide the great majority of necessary nutrients as she starts to sample a variety of new foods. Though your baby will no doubt greatly enjoy the introduction of new tastes and textures in her life, her experiences with solid food are still just practice sessions for the future. It’s important to make sure she continues getting enough breast milk to meet her nutritional needs.

Introducing foods

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breastfeeding as the sole source of nutrition for your baby for about 6 months. When you add solid foods to your baby’s diet, continue breastfeeding until at least 12 months. You can continue to breastfeed after 12 months if you and your baby desire. Check with your child’s doctor about vitamin D and iron supplements during the first year.

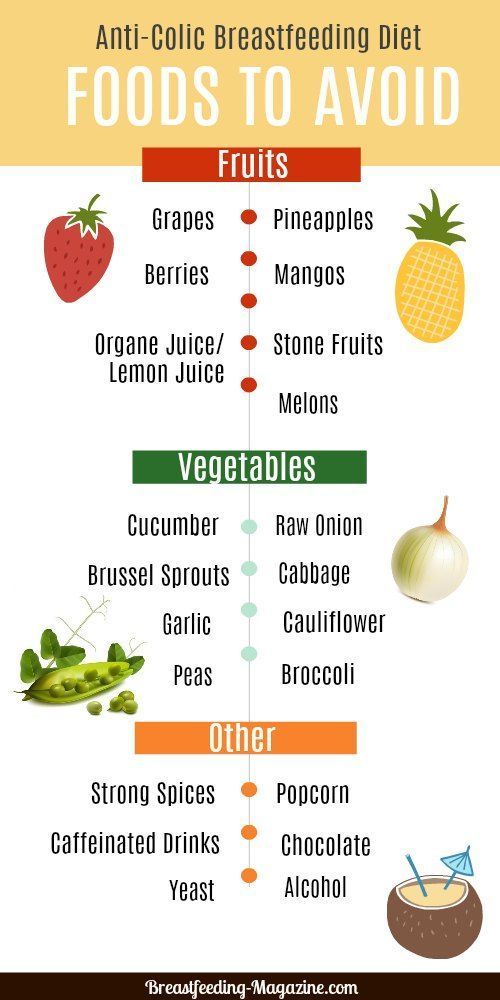

Parents with food allergies are often advised to avoid foods that commonly cause allergic reactions (such as cow’s milk, dairy products, and foods made from peanuts or other nuts). But recent research found that the late introduction of certain foods may actually increase your baby’s risk for food allergies and inhaled allergies. You should discuss any concerns with your pediatrician.

If no allergies are present, simply observe your baby for indications that she is interested in trying new foods and then start to introduce them gradually, one by one. Signs that the older baby is ready for solids include sitting up with minimal support, showing good head control, trying to grab food off your plate, or turning her head to refuse food when she is not hungry. Your baby may be ready for solids if she continues to act hungry after breastfeeding. The loss of the tonguethrusting reflex that causes food to be pushed out of her mouth is another indication that she’s ready to expand her taste experience.

Your baby may be ready for solids if she continues to act hungry after breastfeeding. The loss of the tonguethrusting reflex that causes food to be pushed out of her mouth is another indication that she’s ready to expand her taste experience.

First foods

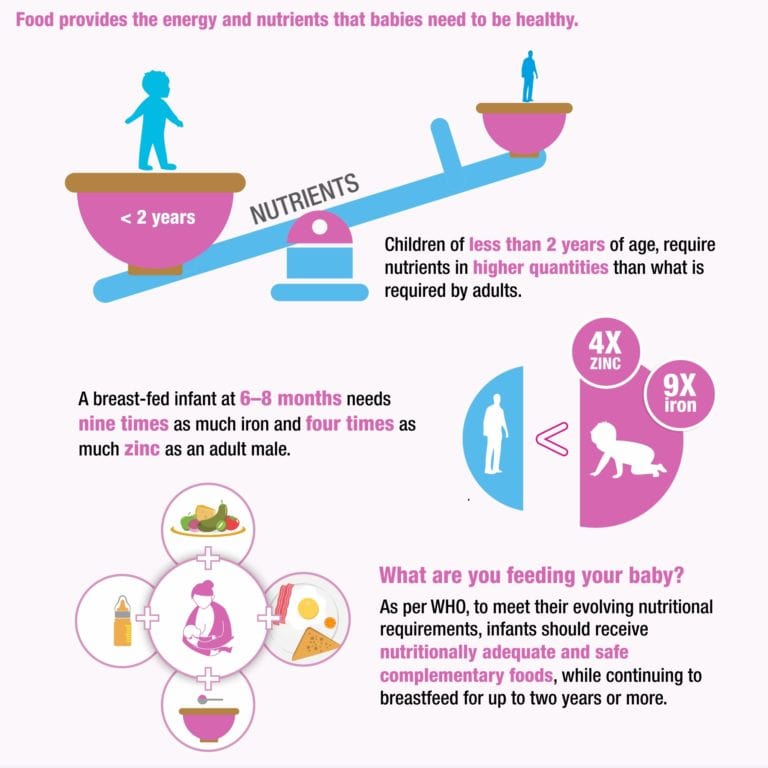

Since most breastfeeding babies’ iron stores begin to diminish at about six months, good first choices for solids are those rich in iron. Current recommendations are that meats, such as turkey, chicken, and beef, should be added as one of the first solids to the breastfed infant’s diet. Meats are good sources of high-quality protein, iron, and zinc and provide greater nutritional value than cereals, fruits, or vegetables.

Iron-fortified infant cereal (such as rice cereal or oatmeal) is another good solid food to complement breast milk. When first starting infant cereal, check the label to make sure that the cereal is a single- ingredient product—that is, rice cereal or oatmeal—and does not contain added fruit, milk or yogurt solids, or infant formula. This will decrease the likelihood of an allergic reaction with the initial cereal feedings. You can mix the cerealwith your breast milk, water, or formula (if you’ve already introduced formula to your baby) until it is a thin consistency. As your baby gets used to the taste and texture, you can gradually make it thicker and increase the amount.

This will decrease the likelihood of an allergic reaction with the initial cereal feedings. You can mix the cerealwith your breast milk, water, or formula (if you’ve already introduced formula to your baby) until it is a thin consistency. As your baby gets used to the taste and texture, you can gradually make it thicker and increase the amount.

Once your child has grown accustomed to these new tastes, gradually expand her choices with applesauce, pears, peaches, bananas, or other mashed or strained fruit, and such vegetables as cooked carrots, peas, and sweet potatoes. Introduce only one new food at a time and wait several days before you add another new food, to make sure your child does not have a negative reaction.

As you learn which foods your baby enjoys and which ones she clearly dislikes, your feeding relationship will grow beyond nursing to a more complex interaction— not a replacement for breastfeeding, certainly, but an interesting addition to it. Remember to keep exposing your baby to a wide variety of foods. Research indicates that some babies need multiple exposures to a new taste before they learn to enjoy it. The breastfed baby has already been experiencing different flavors in the mother’s breast milk, based upon her diet, so solid foods often have a familiar taste when introduced to the breastfed baby.

Research indicates that some babies need multiple exposures to a new taste before they learn to enjoy it. The breastfed baby has already been experiencing different flavors in the mother’s breast milk, based upon her diet, so solid foods often have a familiar taste when introduced to the breastfed baby.

Babies need only a few spoonfuls as they begin solids. Since these first foods are intended as complements and not replacements for your breast milk, it’s best to offer them after a late afternoon or evening feeding, when your milk supply is apt to be at its lowest and your baby may still be hungry.

Some pediatricians recommend an iron supplement. If this is the case, be careful to give the exact dose prescribed by your doctor. Always store iron and vitamin preparations out of the reach of young children in the household, since overdoses can be toxic.

You may find that the number of breastfeedings will gradually decrease as her consumption of solid food increases. A baby who nursed every two to three hours during early infancy may enjoy three or four meals of breast milk per day (along with several snacks) by her twelfth month.

Unless you intend to wean her soon, be sure to continue breastfeeding whenever she desires, to ensure your continuing milk supply. To ease breast discomfort, it may become necessary to express a small amount of milk manually on occasion, if her decreasing demand leaves you with an oversupply. Breast comfort is another reason why a gradual introduction of solid foods is advisable, since it allows your body time to adapt to changing demands. Over the span of several months, a readjustment in the supply-and-demand relationship can take place smoothly and painlessly.

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Breastfeeding FAQs: Solids and Supplementing (for Parents)

Breastfeeding is a natural thing to do, but it still comes with its fair share of questions. Here's what you need to know about about introducing formula, solids, and more.

Here's what you need to know about about introducing formula, solids, and more.

Is it OK to Give My Baby Breast Milk and Formula?

Breast milk is the best nutritional choice for babies. But in some cases, breastfeeding (or exclusive breastfeeding) isn’t possible or an option. What’s best for your baby's health and happiness is, in large part, whatever works for your family. So if you need to supplement, your baby will be fine and healthy, especially if it means less stress for you.

Babies who need supplementation may do well with a supplemental nursing system. This is when moms place a small tube by their nipple that delivers pumped milk or formula while a baby is breastfeeding.

Babies also can get pumped milk or formula by bottle. But it’s a good idea to wait until your baby has gotten used to and is good at breastfeeding. Lactation professionals recommend waiting until a baby is about 3-4 weeks old before offering artificial nipples of any kind (including pacifiers).

If I Give My Baby Formula, How Do I Start?

If you're using formula because you're not producing the amount of milk your baby needs, nurse first. Then, give any pumped milk you have and make up the difference with formula as needed.

If you're stopping a breastfeeding session or are weaning from breastfeeding altogether, begin to replace breastfeeding with bottle feeds. As you do this, pump to reduce uncomfortable engorgement. Engorgement is when your breasts overfill with milk and other fluids and get painful, swollen, warm, or hard. This can lead to problems with plugged ducts (when the ducts won’t drain well or at all) or a breast condition called mastitis.

When you reduce the number of nursing sessions, your milk supply will decrease. Your body will adapt to produce just enough milk to fit your new feeding schedule.

How Might a Diet With Formula Affect My Baby?

Starting your breastfed baby on formula can cause some change in the frequency, color, and consistency of your baby’s poop. Be sure to talk your doctor, though, if your baby has trouble pooping.

Be sure to talk your doctor, though, if your baby has trouble pooping.

If your baby refuses formula alone, you can try mixing some of your pumped breast milk with it to help the baby get used to the new taste.

Is it OK for Me to Give My Baby the First Bottle?

If possible, have someone else give the first bottle. This is because babies can smell their mothers and they're used to receiving breast milk from mom, not a bottle. So try to have someone else — like a caregiver or partner — give the first bottle.

Also consider being out of the house or out of sight when your baby takes that first bottle, since your little one will wonder why you're not doing the feeding as usual. Depending on how your baby takes to the bottle, you might need to keep doing this until your baby gets used to bottle feeding.

If your baby has a hard time adjusting to this new form of feeding, be patient and keep trying. Talk to your doctor if you have questions.

Does My Breastfed Baby Need Supplements?

Breast milk contains many vitamins and minerals. But it’s a good idea to give a daily supplement for some nutrients that may be lacking. It all depends on your baby’s age.

But it’s a good idea to give a daily supplement for some nutrients that may be lacking. It all depends on your baby’s age.

Here are some guidelines:

- Vitamin D. Breastfed babies need to take a daily vitamin D supplement. Vitamin D is added to infant formulas. Vitamin D is made by the body when the skin is exposed to sunlight, but it is not safe for infants under 6 months to be in direct sunlight. (After 6 months, use sunscreen when in the sun to protect your baby’s sensitive skin).

- Iron. Iron is a mineral found in breastmilk during the first 4 months of life. After that, babies need an iron supplement until they begin eating enough iron-rich foods (such as cereals or meats) when they’re around 6 months old. If your baby gets a mix of breast milk and iron-fortified formula, talk to your doctor about whether your little one needs a supplement. After they start on solids, some babies still need iron supplements if they don’t eat enough iron-rich foods.

You doctor can tell you if your baby is getting enough iron.

You doctor can tell you if your baby is getting enough iron. - Fluoride. Babies younger than 6 months do not need a fluoride supplement. After your baby is 6 months old, you can start supplementing with fluoride if your water supply lacks fluoride. Well water, bottled water, tap water in some communities, and ready-to-feed formulas do not have fluoride.

It’s important to find out if your water supply has fluoride in it. You can ask your doctor, dentist, or local water utility agency if the water in your community is fluoridated. Giving a child too much fluoride can cause white marks on the teeth, so there is no need to give a fluoride supplement if your child gets enough fluoride from water.

When Should I Introduce Solid Foods?

The best time to introduce solid foods is when your baby has the skills needed to eat, usually between 4 and 6 months of age. This is when your baby:

- has good head and neck control

- can sit up

- has lost the tongue-thrust reflex (which causes babies to push food out of the mouth)

- has the motor skills needed to transfer food to the back of the mouth to swallow

- shows an interest in food (by watching others eat, reaching for food, or opening the mouth as food approaches)

By this age, babies usually weigh twice their birth weight, or close to it.

Wait until your baby is at least 4 months old and shows these signs of readiness before starting solids. Many babies exclusively breastfeed until 6 months of age, which is perfectly healthy.

Babies who start solid foods before 4 months are at a higher risk for obesity and other problems later on. They also aren't coordinated enough to safely swallow solid foods and may choke on the food or inhale it into their lungs.

How Should I Start Solids?

When the time is right, start with a single-grain, iron-fortified baby cereal. Rice cereal has traditionally been the first food for babies, but you can start with any you prefer. Start with 1 or 2 tablespoons of cereal mixed with breast milk, formula, or water. Never add cereal to a baby's bottle unless your doctor recommends it.

Another good first option is an iron-rich puréed meat. Feed your baby with a small baby spoon.

At this stage, solids should be fed after a nursing session, not before. That way, your baby fills up on breast milk, which should be your baby's main source of nutrition until age 1.

When your baby gets the hang of eating the first food, introduce others, such as puréed fruits, vegetables, beans, lentils, or yogurt. Wait a few days between introducing new foods to make sure your baby doesn't have an allergic reaction.

Experts recommend introducing common food allergens to babies when they're 4–6 months old. This includes babies with a family history of food allergies. In the past, they thought that babies should not get such foods (like eggs, peanuts, and fish) until after the first birthday. But recent studies suggest that waiting that long could make a baby more likely to develop food allergies.

Offer these foods to your baby as soon as your little one starts eating solids. Make sure they're served in forms that your baby can easily swallow. You can try a small amount of peanut butter mixed into fruit purée or yogurt, for example, or soft scrambled eggs.

When Can I Give My Baby Water?

In their first few months, babies usually don't need extra water. Breast milk and formula supply all the fluids that your baby needs. On very hot days, most babies do well with extra feedings.

Breast milk and formula supply all the fluids that your baby needs. On very hot days, most babies do well with extra feedings.

When your baby starts eating solid foods, you can offer a few ounces of water between feedings, but don't force it.

What About Juice?

Fruit juices are not recommended for babies. Juice offers no health benefits, even to older children. Juice can fill them up (leaving little room for more nutritious foods), promote obesity, cause diarrhea, and even put a baby at risk for cavities when teeth start coming in.

Is it possible for a nursing mother to eat baby food?

The well-being of the baby directly depends on how well the mother eats during lactation. In order for a child to grow up strong, nutrition must be balanced, so as not to suffer with the stomach - products must be carefully selected. But it’s not easy for an already busy mom to constantly think about what you can eat and what you can’t, so many people wonder if a nursing mother can eat baby food for feeding - after all, it is made from neutral products and many just like the delicate taste of vegetable purees . nine0003

nine0003

Dry initial milk formula adapted by Valio Baby 1 NutriValio for feeding children from birth to 6 months More

Follow-up dry milk formula adapted by Valio Baby 2 NutriValio for feeding children from 6 to 12 months More

Dry milk drink "Baby milk" Valio Baby 3 NutriValio for feeding children over 12 months Read more

Pros and cons of jar food

There is nothing wrong with the fact that a mother willingly eats food for babies, in fact, no. The main thing is not to go to extremes.

Ready-made baby food has obvious advantages:

- neutral composition;

- does not contain salt, sugar, pepper;

- additional source of nutrients;

- saving time.

The disadvantage of ready-made food in jars is that it does not cover the needs of an adult organism for nutrients. One way or another, you need a variety of foods, including solid ones, so that the intestines do not “get lazy” and work fully. Baby food for a nursing mother is only suitable as an additional source of vitamins and minerals.

Ideally, after the birth of the baby and throughout the period of breastfeeding, the mother should eat in the same way as during pregnancy - often and little by little. You should not try to eat “for two” - just add 500-600 kcal to the daily energy norm for non-pregnant women. nine0003 #PROMO_BLOCK#

Milk formula in the diet of a nursing mother

In situations where the mother's body is depleted - for example, due to difficult childbirth, with a woman's poor appetite, or if the child does not respond well to food, formula milk can be added to the diet. Finnish infant milk formulas Valio Baby are designed for babies from birth to 3 years old, but can also be used as an additional source of energy for nursing mothers. Valio Baby milk contains a lot of useful substances for good growth and development of the child: proteins, Omega-3 and Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, minerals for the baby to be strong, and a probiotic for proper bowel function. All nutritional components are natural. However, the product does not contain palm oil, the use of which in the food industry has caused a lot of criticism in the medical community. nine0003

Valio Baby milk contains a lot of useful substances for good growth and development of the child: proteins, Omega-3 and Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, minerals for the baby to be strong, and a probiotic for proper bowel function. All nutritional components are natural. However, the product does not contain palm oil, the use of which in the food industry has caused a lot of criticism in the medical community. nine0003

Some mothers drink cow's or goat's milk to gain strength or increase their own milk production. There is even a common myth that tea with milk increases lactation. However, this is nothing more than a myth. Firstly, the process can be facilitated with the help of any warm liquid drunk shortly before feeding - even if it is ordinary water. Secondly, the use of unfermented cow's milk can spoil the mother's digestion and, as a result, cause intestinal colic in the newborn. Adapted milk formulas are cleared of phosphorus, which is found in large quantities in cows' milk and prevents the absorption of vitamin D and calcium. nine0003

nine0003

Animal milk is not always well absorbed by an adult body - so why not replace it with a specially prepared pure product that contains so much that is valuable for the health of a nursing mother?

3.3 23

FoodShare:

nine0004 printYou might be interested

Author: Reetta Tikanmäki

Palm oil in baby food

Infant milk formulas are made from cow's milk. However, in terms of fat composition, it differs significantly from that of the mother.

Read

Author: Oksana Ivargizova

How to choose a formula for your baby

Breast milk is the best food for a newborn baby. It contains all the necessary nutritional components that fully meet the needs of the child and are necessary for his healthy and harmonious development.

It contains all the necessary nutritional components that fully meet the needs of the child and are necessary for his healthy and harmonious development.

Read

Show all

Breast milk and formula: what do they have in common?

1 Cribb VL et al. Contribution of inappropriate complementary foods to the salt intake of 8-month-old infants. EUR J Clin Nutr . 2012;66(1):104. - Cribb V.L. et al., "Effects of inappropriate complementary foods on salt intake in 8-month-old infants". Yur J Klin Nutr. 2012;66(1):104.

2 Lönnerdal B. Nutritional and physiologic significance of human milk proteins. Am J Clin Nutr . 2003;77(6):1537 S -1543 S - Lönnerdal B., "Biologically active proteins of breast milk". F Pediatrician Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7.

F Pediatrician Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7.

3 Savino F et al. Breast milk hormones and their protective effect on obesity. Int J Pediatric Endocrinol. 2009;2009:327505. - Savino F. et al., "What role do breast milk hormones play in protecting against obesity." Int J Pediatrician Endocrinol. 2009;2009:327505.

4 Hassiotou F, Hartmann PE. At the Dawn of a New Discovery: The Potential of Breast Milk Stem Cells. Adv Nutr . 2014;5(6):770-778. - Hassiot F, Hartmann PI, "On the threshold of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells." Adv. 2014;5(6):770-778.

5 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clinic Transl Immunology . - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk. " Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

" Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

6 Pannaraj PS et al. Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(7):647-654. - Pannaraj P.S. et al., "Bacterial communities in breast milk and their association with the emergence and development of the neonatal gut microbiome". nine0069 JAMA pediatric. 2017;171(7):647-654.

7 Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama.Glycobiology. 2012;22(9):1147-1162. - Bode L., "Oligosaccharides in breast milk: a sweet mother for every baby." Glycobiology (Glycobiology). 2012;22(9):1147-1162.

8 Deoni SC et al. Breastfeeding and early white matter development: A cross-sectional study. neuroimage. nine0069 2013;82:77-86. - Deoni S.S. et al., Breastfeeding and early white matter development: a cross-sectional study. Neuroimaging. 2013;82:77-86.

Neuroimaging. 2013;82:77-86.

9 Birch E et al. Breast-feeding and optimal visual development. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30(1):33-38. - Birch, I. et al., "Breastfeeding and Optimum Vision Development." J Pediatrician Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30(1):33-38.

10 Sánchez CL et al. The possible role of human milk nucleotides as sleep inducers. Nutr Neurosci . 2009;12(1):2-8. - Sanchez S.L. et al., "Nucleotides in breast milk may help the baby fall asleep." Nutr Neurosai. 2009;12(1):2-8.

11 Moukarzel S, Bode L. Human Milk Oligosaccharides and the Preterm Infant: A Journey in Sickness and in Health. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(1):193-207. - Mukarzel S., Bode L., "Breast milk oligosaccharides and the full-term baby: a path to illness and health." Klin Perinatol (Clinical perinatology). 2017;44(1):193-207.

12 Beck KL et al. Comparative Proteomics of Human and Macaque Milk Reveals Species-Specific Nutrition during Postnatal Development. J Proteome Res . 2015;14(5):2143-2157. - Beck K.L. et al., "Comparative proteomics of human and macaque milk demonstrates species-specific nutrition during postnatal development." nine0069 G Proteome Res. 2015;14(5):2143-2157.

Comparative Proteomics of Human and Macaque Milk Reveals Species-Specific Nutrition during Postnatal Development. J Proteome Res . 2015;14(5):2143-2157. - Beck K.L. et al., "Comparative proteomics of human and macaque milk demonstrates species-specific nutrition during postnatal development." nine0069 G Proteome Res. 2015;14(5):2143-2157.

13 Michaelsen KF, Greer FR. Protein needs early in life and long-term health. Am J Clin Nutr . 2014;99(3):718 S -722 S . - Mikaelsen KF, Greer FR, Protein requirements early in life and long-term health. Am J Clean Nutr. 2014;99(3):718S-722S.

14 Howie PW et al. Positive effect of breastfeeding against infection. BMJ .1990;300(6716):11-16. — Howie PW, "Breastfeeding as a defense against infectious diseases. " BMJ. 1990;300(6716):11-16.

" BMJ. 1990;300(6716):11-16.

15 Duijts L et al. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in infancy. Pediatrics , 2010;126(1): e 18-25. - Duitz L. et al., "Prolonged exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in the first year of life." nine0069 Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2010;126(1):e18-25.

16 Ladomenou F et al. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child . 2010;95(12):1004-1008. - Ladomenu, F. et al., "The effect of exclusive breastfeeding on infection protection in infancy: a prospective study." Arch Dis Child.2010;95(12):1004-1008.

17 Vennemann MM et al. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome?. Pediatrics . 2009;123(3): e 406- e 410. - Wennemann M.M. et al., "Does Breastfeeding Reduce the Risk of Sudden Infant Death?" Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2009;123(3):e406-e410.

- Wennemann M.M. et al., "Does Breastfeeding Reduce the Risk of Sudden Infant Death?" Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2009;123(3):e406-e410.

18 Straub N et al. Economic impact of breast-feeding-associated improvements of childhood cognitive development, based on data from the ALSPAC. Br J Nutr . 2016;1-6. - Straub N. et al., "Economic Impact of Breastfeeding-Associated Child Cognitive Development (ALSPAC)". Br J Nutr . 2016;1-6.

19 Heikkilä K et al. Breast feeding and child behavior in the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child . 2011;96(7):635-642 - Heikkila K. et al., Breastfeeding and Child Behavior in a Millennial Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(7):635-642.

20 Singhal A et al. Infant nutrition and stereoacuity at age 4–6 y. Am J Clin Nutr , 2007;85(1):152-159. - Singhal A. et al., Nutrition in infancy and stereoscopic visual acuity at 4-6 years of age. nine0069 Am F Clean Nutr. 2007;85(1):152-159.

Am J Clin Nutr , 2007;85(1):152-159. - Singhal A. et al., Nutrition in infancy and stereoscopic visual acuity at 4-6 years of age. nine0069 Am F Clean Nutr. 2007;85(1):152-159.

21 Peres KG et al. Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Acta Paediatr . 2015;104(467):54-61. - Perez K.G. et al., "The impact of breastfeeding on malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):54-61.

22 Horta B et al. nine0069 Long - term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Acta Paediatr . 2015;104(467):30-37. - Horta B.L. et al., "Long-term effects of breastfeeding and their impact on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. " Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

" Akta Pediatr. 2015;104(S467):30-37.

23 Lund-Blix NA. Infant feeding in relation to islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible children: the MIDIA Study. Diabetes Care . 2015;38(2):257-263. - Lund-Blix N.A. et al., "Breastfeeding in the context of isolated autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in genetically predisposed children: a study MIDIA ". Diabitis Care. 2015;38(2):257-263.

24 Amitay EL, Keinan-Boker L. Breastfeeding and Childhood Leukemia Incidence: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review0. JAMA96 Pediatr 2015;169(6): e 151025. - Amitai I.L., Keinan-Boker L., "Breastfeeding and incidence of childhood leukemia: a meta-analysis and systematic review". JAMA Pediatrics 2015;169(6):e151025.

25 Bener A et al. Does continued breastfeeding reduce the risk for childhood leukemia and lymphomas? Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60(2):155-161. - Bener A. et al., "Does long-term breastfeeding reduce the risk of leukemia and lymphoma in a child?". Minerva Pediatrician. 2008;60(2):155-161.

2008;60(2):155-161. - Bener A. et al., "Does long-term breastfeeding reduce the risk of leukemia and lymphoma in a child?". Minerva Pediatrician. 2008;60(2):155-161.

26 Dewey KG. Energy and protein requirements during lactation. Annu Rev Nutr . 1997;17:19-36. - Dewey K. J., "Energy and Protein Requirements During Lactation". Anna Rev Nutr. 1997 Jul;17(1):19-36.

27 Victoria CG et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475-490. - Victor S.J. et al., "Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms and long-term effects". Lancet 2016;387(10017):475-490.

28 Jordan SJ et al. Breastfeeding and Endometrial Cancer Risk: An Analysis From the Epidemiology of Endometrial Cancer Consortium. Obstet Gynecol . 2017;129(6):1059-1067. — Jordan S.J. et al., "Breastfeeding and the risk of endometrial cancer: an analysis of epidemiological data from the Endometrial Cancer Consortium". Obstet Ginekol (Obstetrics and Gynecology). 2017;129(6):1059-1067.

2017;129(6):1059-1067. — Jordan S.J. et al., "Breastfeeding and the risk of endometrial cancer: an analysis of epidemiological data from the Endometrial Cancer Consortium". Obstet Ginekol (Obstetrics and Gynecology). 2017;129(6):1059-1067.

29 Li DP et al. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev . 2014;15(12):4829-4837. - Lee D.P. et al., "Breastfeeding and the risk of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies." Asia Pas W Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4829-4837.

30 Peters SAE et al. Breastfeeding and the Risk of Maternal Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Study of 300,000 Chinese Women. J Am Heart Assoc . 2017;6(6). - Peters S.A. et al., "Breastfeeding and Maternal Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Study of 300,000 Chinese Women". J Am Hart Assoc. 2017;6(6):e006081. nine0069

2017;6(6). - Peters S.A. et al., "Breastfeeding and Maternal Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Study of 300,000 Chinese Women". J Am Hart Assoc. 2017;6(6):e006081. nine0069

31 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [Internet]. Surgeon General Breastfeeding factsheet ; 2011 Jan 20 — Department of Health and Human Services [Internet], Breastfeeding Facts from the Chief Medical Officer, 20 January 2011 [cited 4 April 2018]

32 Doan T et al. nine0069 Breast-feeding increases sleep duration of new parents. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs . 2007;21(3):200-206. - Dawn T. et al., "Breastfeeding increases parental sleep duration." G Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2007;21(3):200-206.

33 Menella JA et al. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics . 2001;107(6): E 88.