Can babies taste food in breast milk

Influence of maternal diet on flavor transfer to amniotic fluid and breast milk and children's responses: a systematic review

. 2019 Mar 1;109(Suppl_7):1003S-1026S.

doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy240.

Joanne M Spahn 1 , Emily H Callahan 2 , Maureen K Spill 2 , Yat Ping Wong 1 , Sara E Benjamin-Neelon 3 , Leann Birch 4 , Maureen M Black 5 , John T Cook 6 , Myles S Faith 7 , Julie A Mennella 8 , Kellie O Casavale 9

Affiliations

Affiliations

- 1 USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, Alexandria, VA.

- 2 Panum Group, Bethesda, MA.

- 3 Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

- 4 University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

- 5 University of Maryland, College Park, MD and RTI International.

- 6 Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA.

- 7 University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY.

- 8 Monell Chemical Senses Center, Philadelphia, PA.

- 9 US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Rockville, MD.

- PMID: 30982867

- DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy240

Free article

Joanne M Spahn et al. Am J Clin Nutr. .

Free article

. 2019 Mar 1;109(Suppl_7):1003S-1026S.

doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy240.

Authors

Joanne M Spahn 1 , Emily H Callahan 2 , Maureen K Spill 2 , Yat Ping Wong 1 , Sara E Benjamin-Neelon 3 , Leann Birch 4 , Maureen M Black 5 , John T Cook 6 , Myles S Faith 7 , Julie A Mennella 8 , Kellie O Casavale 9

Affiliations

- 1 USDA, Food and Nutrition Service, Alexandria, VA.

- 2 Panum Group, Bethesda, MA.

- 3 Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

- 4 University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

- 5 University of Maryland, College Park, MD and RTI International.

- 6 Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA.

- 7 University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY.

- 8 Monell Chemical Senses Center, Philadelphia, PA.

- 9 US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Rockville, MD.

- PMID: 30982867

- DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy240

Abstract

Background: Maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation may provide the earliest opportunity to positively influence child food acceptance.

Objective: Systematic reviews were completed to examine the relation among maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation, amniotic fluid flavor, breast-milk flavor, and children's food acceptability and overall dietary intake.

Design: A literature search was conducted in 10 databases (e.g., PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and CINAHL) to identify articles published from January 1980 to June 2017. Data from each included study were extracted, risk of bias assessed, evidence synthesized qualitatively, conclusion statements developed, and strength of the evidence graded.

Data from each included study were extracted, risk of bias assessed, evidence synthesized qualitatively, conclusion statements developed, and strength of the evidence graded.

Results: Eleven and 15 articles met a priori criteria for inclusion to answer questions related to maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation, respectively.

Conclusions: Limited but consistent evidence indicates that flavors (alcohol, anise, carrot, garlic) originating from the maternal diet during pregnancy can transfer to and flavor amniotic fluid, and fetal flavor exposure increases acceptance of similarly flavored foods when re-exposed during infancy and potentially childhood. Moderate evidence indicates that flavors originating from the maternal diet during lactation (alcohol, anise/caraway, carrot, eucalyptus, garlic, mint) transmit to and flavor breast milk in a time-dependent manner. Moderate evidence indicates that infants can detect diet-transmitted flavors in breast milk within hours of a single maternal ingestion (alcohol, garlic, vanilla, carrot), within days after repeated maternal ingestion (garlic, carrot juice), and within 1-4 mo postpartum after repeated maternal ingestion (variety of vegetables including carrot) during lactation. Findings may not generalize to all foods and beverages. Conclusions cannot be drawn to describe the relationship between mothers' diet during either pregnancy or lactation and children's overall dietary intake.

Moderate evidence indicates that infants can detect diet-transmitted flavors in breast milk within hours of a single maternal ingestion (alcohol, garlic, vanilla, carrot), within days after repeated maternal ingestion (garlic, carrot juice), and within 1-4 mo postpartum after repeated maternal ingestion (variety of vegetables including carrot) during lactation. Findings may not generalize to all foods and beverages. Conclusions cannot be drawn to describe the relationship between mothers' diet during either pregnancy or lactation and children's overall dietary intake.

Keywords: alcohol; beverages; breast milk; flavor transfer; flavors; food acceptance; foods; maternal and child dietary intake; systematic review; taste.

© American Society for Nutrition 2019.

Similar articles

-

Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants.

Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Mennella JA, et al. Pediatrics. 2001 Jun;107(6):E88. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e88. Pediatrics. 2001. PMID: 11389286 Free PMC article.

-

Learning to like vegetables during breastfeeding: a randomized clinical trial of lactating mothers and infants.

Mennella JA, Daniels LM, Reiter AR. Mennella JA, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jul;106(1):67-76. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.143982. Epub 2017 May 17. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017. PMID: 28515063 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

-

Maternal Diet during Pregnancy and Lactation and Risk of Child Food Allergies and Atopic Allergic Diseases: A Systematic Review [Internet].

Donovan S, Dewey K, Novotny R, Stang J, Taveras E, Kleinman R, Raghavan R, Nevins J, Scinto-Madonich S, Butera G, Terry N, Obbagy J.

Donovan S, et al. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020 Jul. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020 Jul. PMID: 35289989 Free Books & Documents. Review.

Donovan S, et al. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020 Jul. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020 Jul. PMID: 35289989 Free Books & Documents. Review. -

The Development of Flavor Perception and Acceptance: The Roles of Nature and Nurture.

Forestell CA. Forestell CA. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2016;85:135-43. doi: 10.1159/000439504. Epub 2016 Apr 18. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2016. PMID: 27088341 Review.

-

Flavor perception in human infants: development and functional significance.

Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Beauchamp GK, et al. Digestion. 2011;83 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):1-6.

doi: 10.1159/000323397. Epub 2011 Mar 10. Digestion. 2011. PMID: 21389721 Free PMC article. Review.

doi: 10.1159/000323397. Epub 2011 Mar 10. Digestion. 2011. PMID: 21389721 Free PMC article. Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Parental Feeding Practices and Children's Eating Behaviours: An Overview of Their Complex Relationship.

Costa A, Oliveira A. Costa A, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Jan 31;11(3):400. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11030400. Healthcare (Basel). 2023. PMID: 36766975 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Third Trimester Fetuses Demonstrate Priming, a Form of Implicit Memory, In Utero.

Gustafsson H, Hammond J, Spicer J, Kuzava S, Werner E, Spann M, Marsh R, Feng T, Lee S, Monk C. Gustafsson H, et al.

Children (Basel). 2022 Oct 31;9(11):1670. doi: 10.3390/children9111670. Children (Basel). 2022. PMID: 36360397 Free PMC article.

Children (Basel). 2022 Oct 31;9(11):1670. doi: 10.3390/children9111670. Children (Basel). 2022. PMID: 36360397 Free PMC article. -

Prenatal programing of motivated behaviors: can innate immunity prime behavior?

Montalvo-Martínez L, Cruz-Carrillo G, Maldonado-Ruiz R, Trujillo-Villarreal LA, Garza-Villarreal EA, Camacho-Morales A. Montalvo-Martínez L, et al. Neural Regen Res. 2023 Feb;18(2):280-283. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.346475. Neural Regen Res. 2023. PMID: 35900403 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Associations of ultra-processed food intake with maternal weight change and cardiometabolic health and infant growth.

Cummings JR, Lipsky LM, Schwedhelm C, Liu A, Nansel TR. Cummings JR, et al.

Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022 May 26;19(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12966-022-01298-w. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022. PMID: 35619114 Free PMC article.

Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022 May 26;19(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12966-022-01298-w. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022. PMID: 35619114 Free PMC article. -

Demographic and clinical parameters are comparable across different types of pediatric feeding disorder.

Galai T, Friedman G, Moses M, Shemer K, Gal DL, Yerushalmy-Feler A, Lubetzky R, Cohen S, Moran-Lev H. Galai T, et al. Sci Rep. 2022 May 21;12(1):8596. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12562-1. Sci Rep. 2022. PMID: 35597792 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Can babies taste what you ate for lunch?

© 2018 – 2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph. D., all rights reserved

D., all rights reserved

Flavors in breast milk? From the food that mothers ingest? Yes, it really happens, and babies can taste the difference. It might even affect their food preferences later in life.

A mother eats a spicy meal, then nurses her baby an hour later. Will the flavors make their way into the breast milk? Will her baby detect undercurrents of garlic? Top notes of ginger and coconut?

The baby probably isn’t mulling it over with the vocabulary of a foodie. But the basic notion isn’t far-fetched. A mother’s diet really can affect the taste of her milk, and babies don’t just notice these flavors. They also respond to them. Here’s how we know.

More garlic-flavored breast milk, please.

What happens if you ask a bunch of breastfeeding mothers to swallow some garlic pills? Researchers tried it, and confirmed through lab analyses that the garlic made its way into the women’s milk. The flavor peaked between 1. 5 to 3 hours after ingestion, at which point the women were asked to feed their 3-month-old babies. And then?

5 to 3 hours after ingestion, at which point the women were asked to feed their 3-month-old babies. And then?

Compared with babies whose mothers had swallowed placebo pills, the “garlic babies” spent more time feeding. They apparently liked the garlic (Mennella and Beauchamp 1991).

A similar experiment suggests that babies enjoy vanilla, too (Mennella and Beauchamp 1996). And when researchers asked lactating women to ingest four different flavor capsules, they found that all four flavors — banana, caraway, anise, and menthol — could be detected in breast milk later on. Banana peaked after just one hour, but the others lasted longer (Hausner et al 2008).

So it seems likely that many food flavors make their way into breast milk. Does this have any lasting effects?

Do babies remember flavors in breast milk, and recognize these flavors when they start eating solid foods?

Julie Mennella and colleagues wanted to find out, so they recruited a group breastfeeding women, and then randomly assigned some of the mothers to drink carrot juice each day for the first 2 months postpartum. Months later, when the babies were 5-6 months old, the researchers brought the babies into the lab for a taste test. On different days, the babies were offered plain cereal and carrot-flavored cereal. What happened next?

Months later, when the babies were 5-6 months old, the researchers brought the babies into the lab for a taste test. On different days, the babies were offered plain cereal and carrot-flavored cereal. What happened next?

All the babies made screwy, disapproving faces when they encountered the carrot-flavored cereal. But compared with babies in a control group, the babies who had been exposed to “carroty” breast milk reacted less negatively (Mennella et al 2001). They seemed to recognize the taste of carrots — more than three months after their mothers had stopped drinking carrot juice.

Menella’s lab obtained similar results in a later study, one in which mothers were instructed to drink four different types of vegetable juice (vegetable, beet, celery, and carrot) for one month during the early weeks postpartum. Later, when the babies were 8 months old, they took the carrot taste test, and — once again — infants in the experimental groups (whose mothers had consumed vegetable juices) showed less negativity in response to carrots (Menella et al 2017).

Does this mean that any amount of exposure to flavors in breast milk will make babies like a given food?

Not necessarily. In the first study, the carrot-exposed babies didn’t eat more carrot-flavored cereal. They just showed fewer negative reactions to the taste. In the second study, the researchers found possible evidence for increased liking, but only for infants whose mothers had consumed vegetable juices from 2 weeks postpartum to 6 weeks postpartum (Menella et al 2017).

And consider what happens if babies are offered something other than carrots. When researchers at the University of Coperhagen tested the effects of caraway exposure on 5-8 month old breastfeeding babies, they found that 10 days of exposure to carroway flavors in breast milk had no impact on the babies’ acceptance of a carroway-flavored purée (Hausner et al 2010).

So the research doesn’t tell us that exposure to flavors in breast milk will make babies like a particular food. But it does support a more fundamental idea — that babies begin learning about food flavors long before they start eating solid foods.

But it does support a more fundamental idea — that babies begin learning about food flavors long before they start eating solid foods.

That shouldn’t surprise us, not if we consider the evidence for prenatal learning about food. Babies develop the ability to taste and smell before they are born, and food flavors can pass through the placenta and into the amniotic fluid (Spahn et al 2019). Studies indicate that newborns are more accepting of flavors they have encountered during gestation. Read more about the fascinating research in my article, “Prenatal learning: Do “pregnancy foods” affect babies’ eating habits?”

Does breastfeeding help shape childhood eating habits?

The caraway study didn’t support a short-term exposure effect, but researchers did notice an interesting difference between breastfed and formula-fed babies: Regardless of whether or not their mothers had consumed carroway, breastfed babies showed a higher initial acceptance of the carroway purée than formula-fed infants did (Hausner et al 2010).

That’s consistent with other research showing that breastfed infants are more likely to accept new foods, and more likely to have varied diets as they get older. For instance, research suggests that infants are less likely to become picky eaters later in life (Forestell 2017). And the longer babies breastfeed, the more likely they are to consume vegetables during early childhood (de Wild et al 2018).

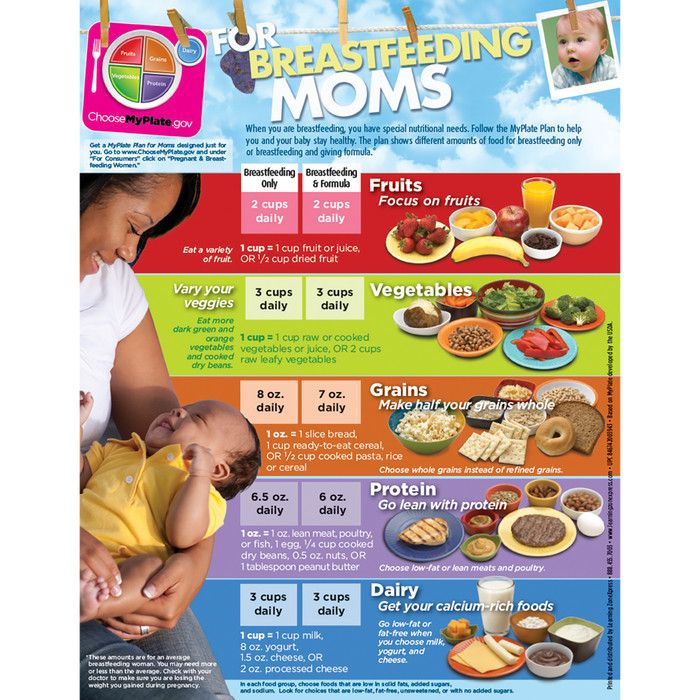

Could this be because the experience of tasting many different foods — experiencing many different flavors in breast milk — prepares babies to sample a variety of solid foods? If so, this could be an important benefit of breastfeeding (Spahn et al 2019; Ventura et al 2021).

In support of the idea, a study tracking the development of more than 1500 children (from infancy to 6 years) found intriguing links between breastfeeding, maternal diet, and child outcomes. The more vegetables that a mother ate at around the 3 months postpartum — and the longer she breastfed her baby — the more likely it was that her child would end up with a diet high in vegetables (Beckman et al 2020).

In particular, among kids who had been breastfed for at least 16 weeks total, each additional serving of vegetables in their mothers’ breastfeeding diets was linked with 22% increased odds of eating a diet high in vegetables at age 6. And this was true even after the researchers made statistical adjustments for the effects of socioeconomic status, the timing of the introduction of solid vegetable foods, and a variety of health-related variables (Beckman et al 2020).

What about babies on formula? Do they have any interesting flavor experiences?

Formula might never taste like garlic or carrots, but different formulas have somewhat different flavors, and these, too, may influence the development of food preferences.

In an experiment on preschoolers, Djin Gie Liem and Julie Mennella asked kids to taste a variety of juices, each characterized by different levels of sweetness and sourness. The researchers found that kids who’d consumed sour-tasting, protein hydrolysate formulas as babies preferred higher concentrations of citric acid in their juice (Liem and Mennella 2002). Kids who’d used a different formula were less likely to enjoy sour juice.

Kids who’d used a different formula were less likely to enjoy sour juice.

A similar study found that kids who had consumed soy-based formulas were more likely to enjoy a bitter-tasting juice (Mennella and Beauchamp 2002).

And other experiments suggest that babies fed hydrolysate formulas are less likely than babies on milk-based formulas to consume pureed broccoli or cauliflower (Mennella et al 2006)

So it appears that a child’s food preferences aren’t purely idiosyncratic or arbitrary. They aren’t just a reflection of individual genetics, or media hype, or even childhood experiences. They are influenced by prenatal events and encounters during infancy — exposure to flavors in breast milk and formula (Forestell 2017).

What else is in breast milk? Read about the nutrients in breast milk here.

References: Flavors in breast milk and formula

Beckerman JP, Slade E, Ventura AK. 2020. Maternal diet during lactation and breast-feeding practices have synergistic association with child diet at 6 years. Public Health Nutr. 23(2):286-294.

Public Health Nutr. 23(2):286-294.

Bell LK, Gardner C, Tian EJ, Cochet-Broch MO, Poelman AAM, Cox DN, Nicklaus S, Matvienko-Sikar K, Daniels LA, Kumar S, Golley RK. 2021. Supporting strategies for enhancing vegetable liking in the early years of life: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Am J Clin Nutr. 113(5):1282-1300.

Cooke LJ, Wardle J, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, and Lawson M. 2004. Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 7(2):295-302.

Forestell CA. 2017.Flavor Perception and Preference Development in Human Infants. Ann Nutr Metab. 70 Suppl 3:17-25.

Forestell CA and Mennella JA. 2007. Early determinants of fruit and vegetable acceptance. Pediatrics 120:1247-1254.

Hausner H, Bredie WLP, Mølgaard C, Petersen MA and Moller P. 2008. Differential transfer of dietary flavour compounds into human breast milk. Physiology and Behavior 95(1-2): 118–124

Hausner H, Nicklaus S, Issanchou S, Mølgaard C, Møller P. 2010. Breastfeeding facilitates acceptance of a novel dietary flavour compound. Clin Nutr. 29(1):141-8.

2010. Breastfeeding facilitates acceptance of a novel dietary flavour compound. Clin Nutr. 29(1):141-8.

Lakkakula AP, Zanovec M, Silverman L, Murphy E, and Tuuri G. 2008. Black children with high preferences for fruits and vegetables are at less risk of being at risk of overweight or overweight. J Am Diet Assoc. 108(11):1912-5.

Liem DG and Mennella JA.2002. Sweet and sour preferences during childhood: role of early experiences. Dev Psychobiol. 41(4):388-95.

Maier AS, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Leathwood PD, Issanchou SN. 2008. Breastfeeding and experience with variety early in weaning increase infants’ acceptance of new foods for up to two months. Clin Nutr. 27(6):849-57.

Mennella JA, Daniels LM, Reiter AR. 2017. Learning to like vegetables during breastfeeding: a randomized clinical trial of lactating mothers and infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 106(1):67-76.

Mennella JA, Kennedy JM and Beauchamp GK. 2006. Vegetable acceptance by infants: effects of formula flavors. Early Hum Dev. 82(7):463-8.

Early Hum Dev. 82(7):463-8.

Mennella JA and Beauchamp GK. 2002. Flavor experiences during formula feeding are related to preferences during childhood. Early Hum Dev. 2002 Jul;68(2):71-82.

Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, and Beauchamp GK. 2001. Prenatal and Postnatal Flavor Learning by Human Infants. Pediatrics. 107(6):E88.

Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. 1996. The human infants’ responses to vanilla flavors in human milk and formula. Infant Behav Dev. 19:13–19.

Mennella JA and Beauchamp GK. 1991. Maternal diet alters the sensory qualities of human milk and the nursling’s behavior.

Spahn JM, Callahan EH, Spill MK, Wong YP, Benjamin-Neelon SE, Birch L, Black MM, Cook JT, Faith MS, Mennella JA, Casavale KO. 2019. Influence of maternal diet on flavor transfer to amniotic fluid and breast milk and children’s responses: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 109(Suppl_7):1003S-1026S.

Sullivan SA and Birch LL. 1994. Infant Dietary Experience and Acceptance of Solid Foods Pediatrics 93 (2): 271-277.

Ventura AK, Phelan S, Silva Garcia K. 2021. Maternal Diet During Pregnancy and Lactation and Child Food Preferences, Dietary Patterns, and Weight Outcomes: a Review of Recent Research. Curr Nutr Rep. 10(4):413-426.

Content of “Flavors in breast milk” last modified 2022

image credits for “Flavors in breast milk”:

image of udon and bok choy by istock / ALLEKO

Portions of the text appeared in previous, older versions of this article by the same author.

Taste development in babies: what do they like best?

The improvement of taste sensations in a small child is as intense as the development of all other senses. The first year of life is a decisive time that can predetermine a person's taste preferences in the future.

In a small child, acquaintance with the world and the acquisition of basic skills is directly related to the development of the senses - hearing, sight, touch, smell and taste. From birth, the baby has basic sensory abilities that will improve throughout the first years of life. Subsequently, the active development of the nervous system, and hence the brain and the system of perception, will provide him with a confident and accurate control of his feelings and sensations.

Subsequently, the active development of the nervous system, and hence the brain and the system of perception, will provide him with a confident and accurate control of his feelings and sensations.

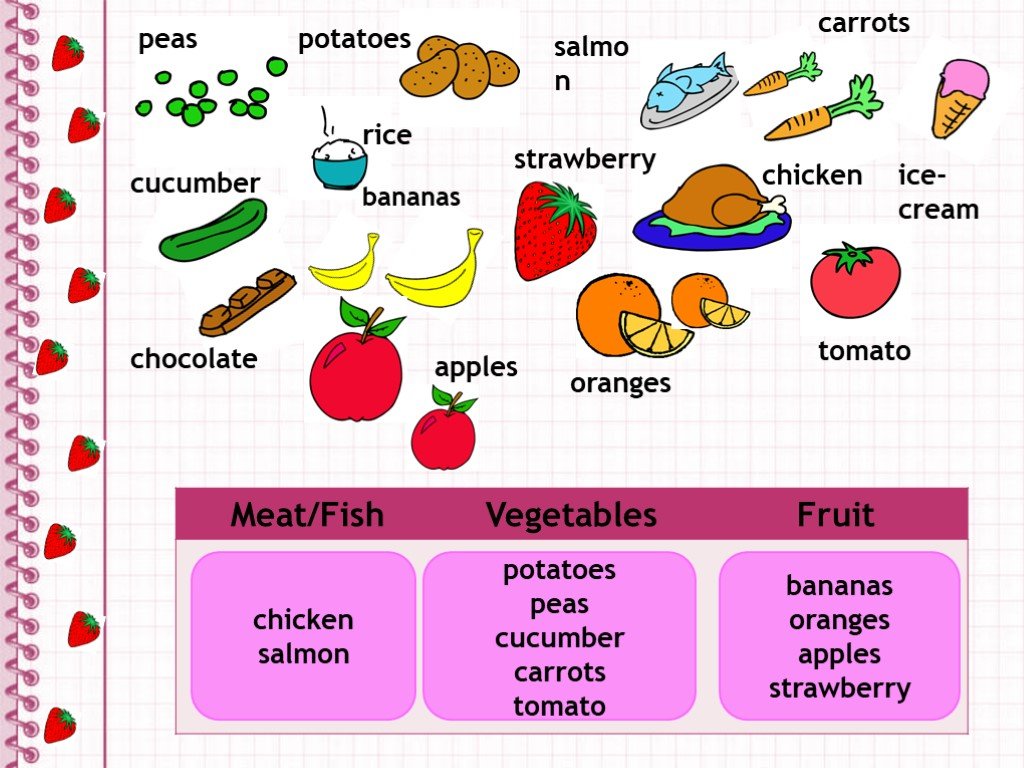

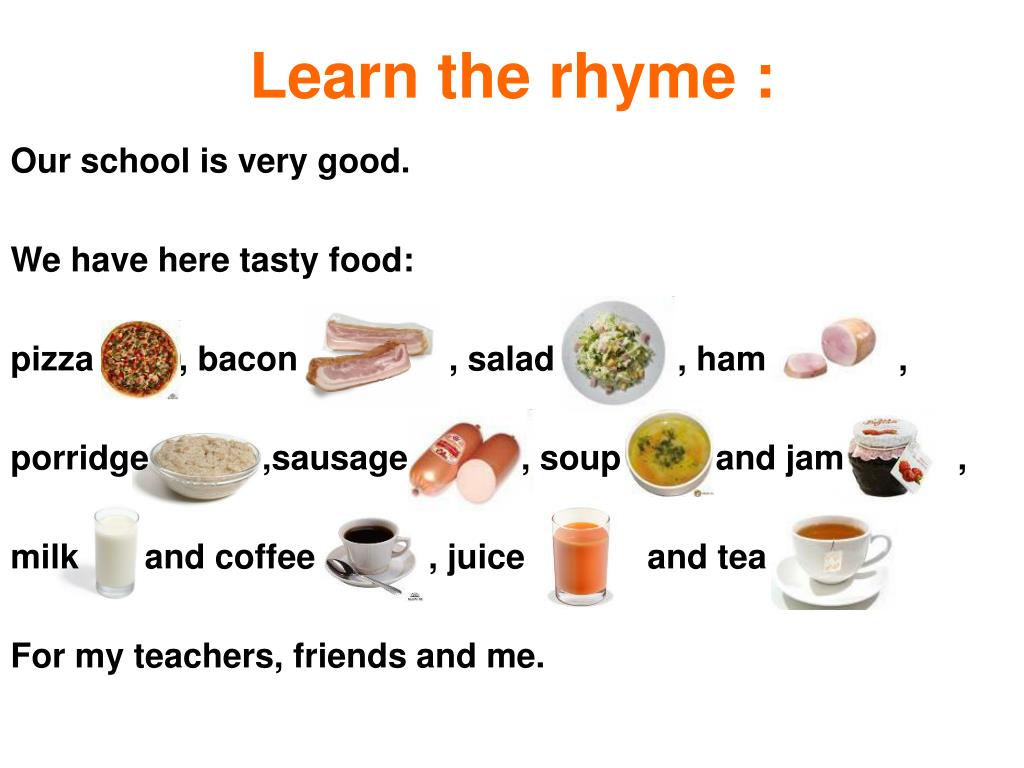

How many flavors does our tongue recognize? Sweet, sour, salty, bitter. Now, one more has officially been added to these four basic tastes, the fifth one is protein or umami (from the Japanese word "umai" - tasty, pleasant). This taste is typical for meat, fish and broths based on them.

Before birth

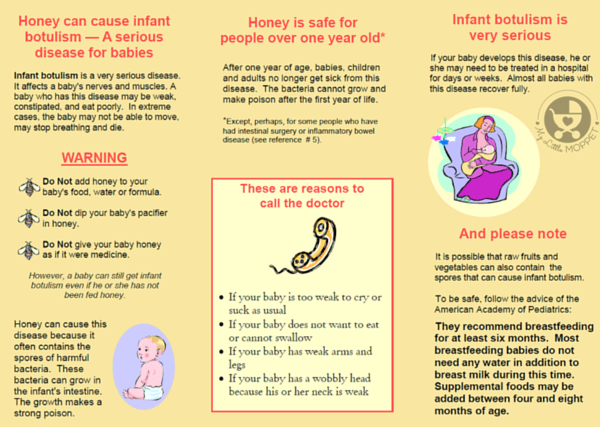

Cells capable of detecting various tastes begin to develop from the seventh week of pregnancy, and by the thirteenth week they are fully functional. At the sixth month of pregnancy, the baby swallows and "inhales" a large amount of amniotic fluid, the taste of which changes depending on what the pregnant woman eats.

MRI techniques have allowed specialists to learn more about the taste preferences of the embryo. For example, he swallows amniotic fluid faster if it tastes sweeter due to his mother's glucose intake. This is a sign that he likes the sweet taste more.

This is a sign that he likes the sweet taste more.

This is how, by swallowing amniotic fluid, the child experiences for the first time what is called taste sensations, which come to him through the mouth and nose. Indeed, the foods that a woman eats change the taste and smell of the amniotic fluid. This exposure introduces the baby to the mother's eating habits.

When a baby is born, he already has some experience of recognizing the different tastes that will be part of his eating habits. For example, babies whose mothers ate a lot of carrots in the last month of pregnancy are likely to prefer this product.

Taste of the newborn

After birth, the baby continues to experience the tastes of his mother's food through breast milk. Breastfed children agree to try different foods faster and more easily than those who ate artificial mixtures. Eating habits acquired during breastfeeding may persist into older age.

Experts call breast milk a "bridge" that connects the period of intrauterine development, when the child received information about the taste of foods through the amniotic fluid, and the time of introduction of complementary foods.

Sweet

From the first days of life, the baby prefers certain tastes. Favorite is sweet. Feeling the sweet taste, the newborn smiles, licks his lips and begins to make sucking movements. The sweet taste makes the child feel comfortable and safe. This calming effect is especially important in the first weeks of life.

Love for sweets is a big plus for a child's development. She allows him to eat with pleasure, which means that in sufficient quantities, the first food in his life is breast milk. Sweet and full-fat milk contains more calories, which is very useful for an actively growing body.

Bitter

Bitter taste causes the strongest disgust reaction in the baby. Bitterness is created by plant toxin molecules and triggers defensive behavior. If you offer a baby something bitter, he will spit it out and scream - this is an innate reaction, as well as sucking, swallowing, salivation. The last three reactions are directed towards eating, and the reaction to a bitter taste is directed towards rejection of inedible foods.

In addition, the signal associated with these reactions is transmitted to the hypothalamus, to the center of negative emotions, which gives rise to a strong negative experience. The feeling of bitterness is indeed a signal that the food is inedible.

An immune response to bitter taste has recently been described. It turns out that the receptors responsible for recognizing bitter not only cause taste sensations, but also activate the immune system. Therefore, it is correct when the medicine has a bitter taste - this is how it additionally activates the immune system, which will complement the action of the active substance of the medicine.

Salty, sour, fatty

But the baby reacts poorly to salty. Baby will like salted water closer to 4 months. Sour taste and umami taste (the taste of meat, fish and broths based on them) cause intermediate reactions.

The greasy taste seems to be more to the children's taste. It is noticed that newborns drink more breast milk of high fat content.

Although most babies like certain tastes, every baby has their own preferences. Some genetic traits can influence taste recognition.

How taste preferences change

Distinguishing tastes (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami) occurs through taste buds located on the tongue, mouth and throat. At birth, a child has more taste buds than an adult, so the baby perceives tastes sharply.

Sense of smell and vision also play an important role in shaping food preferences.

During the first year of life, the child mainly eats sweet food - breast milk. Breast milk is a source of various tastes and aromas, and this affects the development of taste sensations and contributes to the full formation of eating behavior.

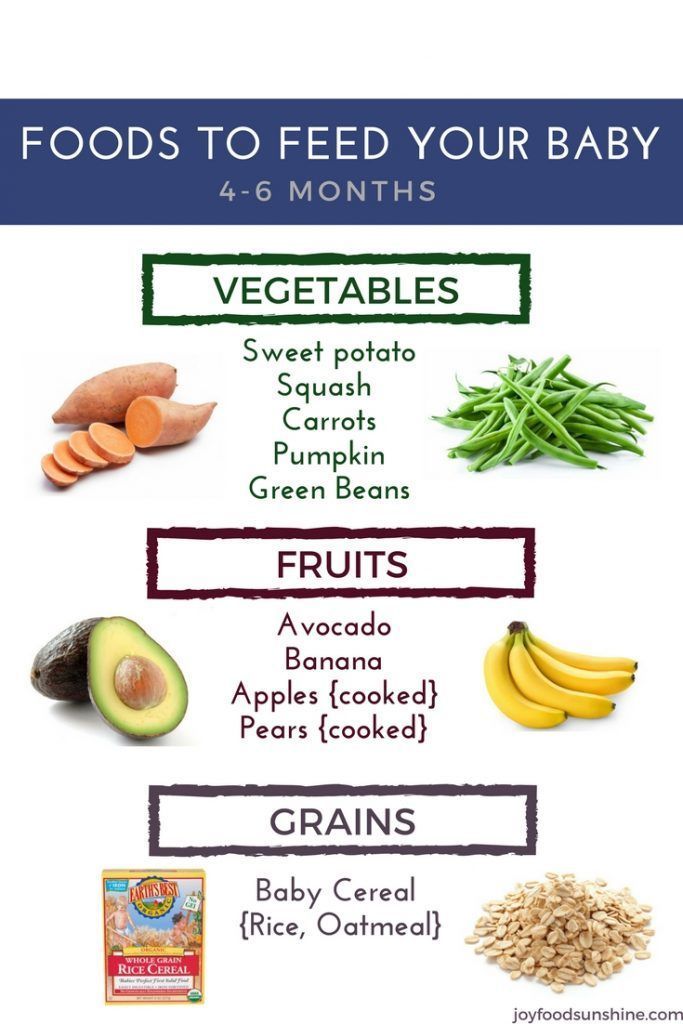

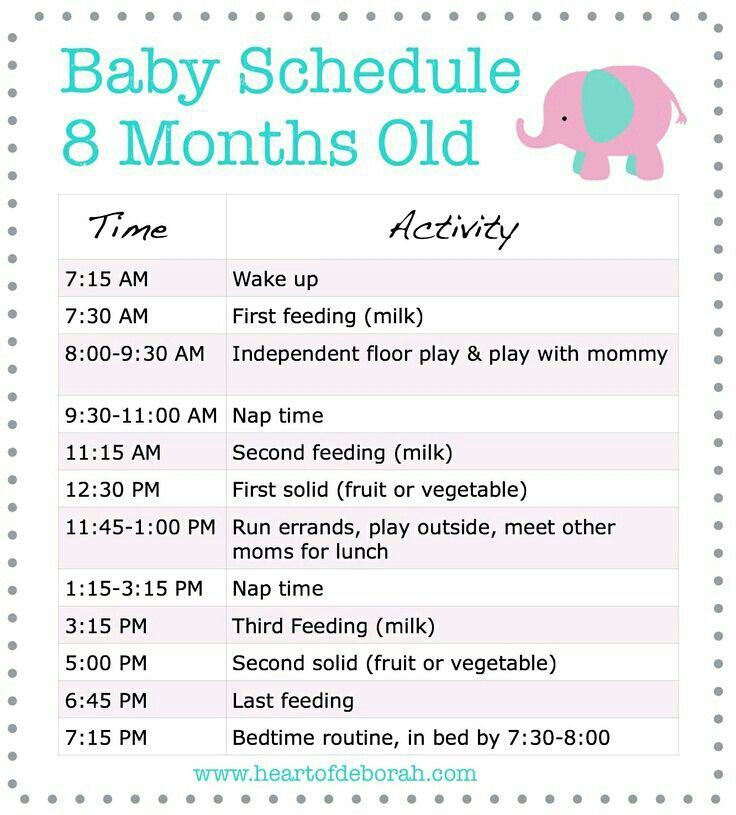

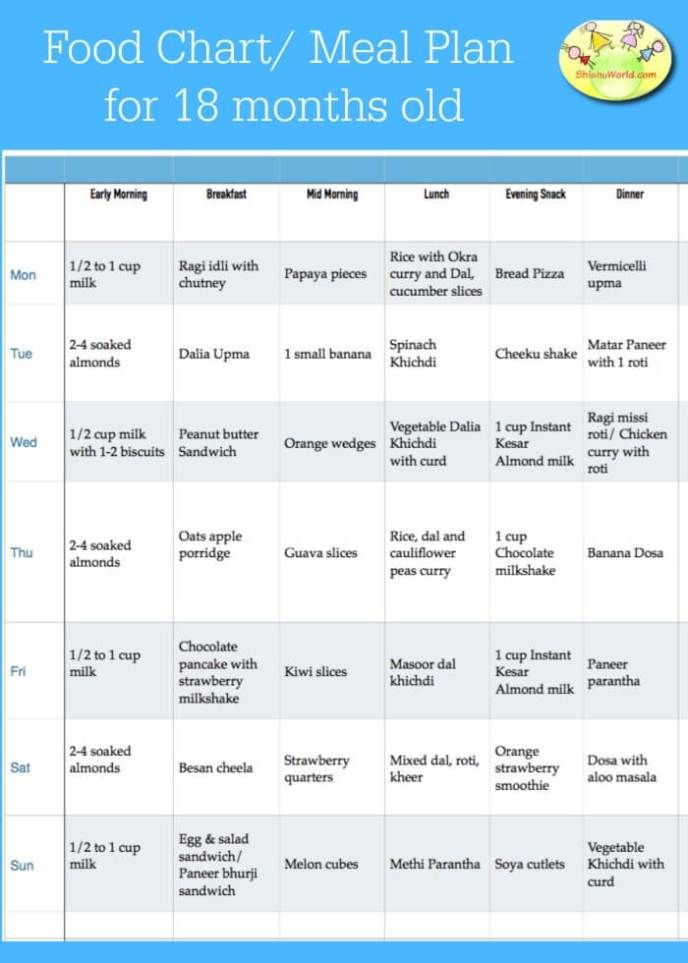

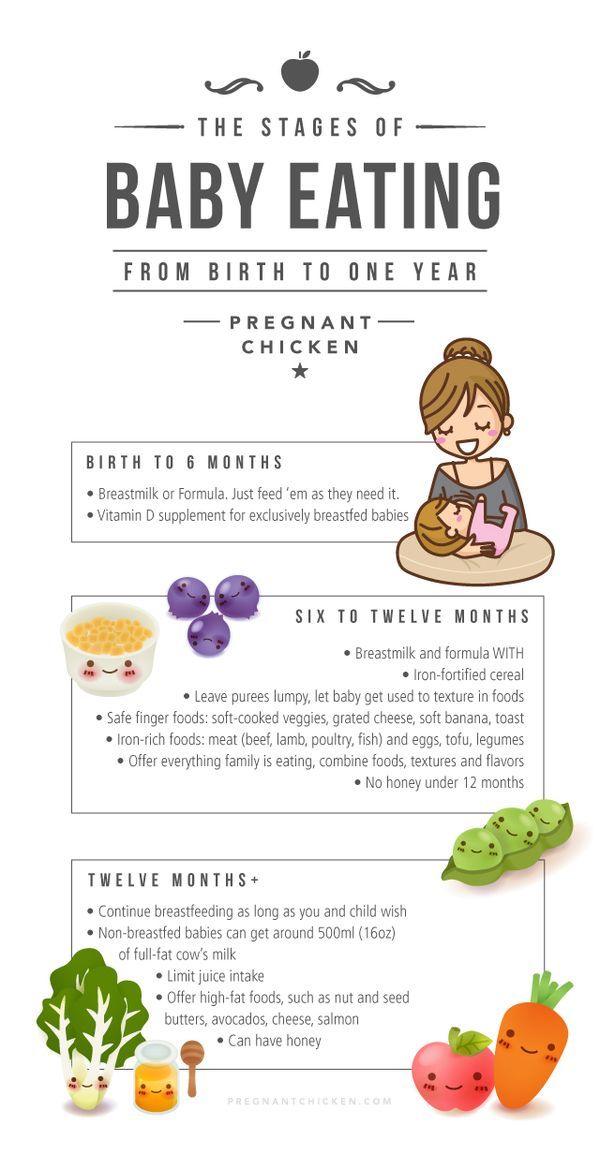

Starting at 6 months, as complementary foods are introduced, the baby begins to become familiar with other taste sensations. Complementary foods should be introduced in a timely manner and include all food groups in accordance with age. Diversity in nutrition is very beneficial for a child. The sooner he learns to recognize different tastes, the better he can develop his sensory system. “Experienced” children are less likely to refuse to try unfamiliar foods and new dishes in the future.

The sooner he learns to recognize different tastes, the better he can develop his sensory system. “Experienced” children are less likely to refuse to try unfamiliar foods and new dishes in the future.

Taste preferences are influenced by both genetic factors and the environment in which the child grows up and the environment in which eating takes place. At the age of up to one and a half years, the child quite easily agrees to try any offered products. If the food is tasty and the child likes it, then he feels good. Such food evokes positive emotions.

The foods that your baby will be introduced to in the first 18 months will determine his gastronomic preferences in adulthood.

In other words, children remember the characteristic taste of the product at a very early age, and the memory of it remains for a long time, influencing the formation of taste preferences in the future. Therefore, try to open different tastes for the baby, even if at first they did not impress him.

The foundations of eating behavior are laid from early childhood under the influence of parents and close relatives, who, with a competent approach, can teach even the most fastidious child to eat properly. It is in our power to diversify the world of the baby, including educating his taste in the broadest sense of the word.

Source:

Site for parents Naître et Grandir

Photo: UNSPLASH, DreamStime

90,000 myths about breast and breastfeedingMyth:

Reality:

MIF:

Madwathing with small breasts or entered nipples is impossible.

REALITY:

The size of the breast does not matter, what is important is the maturity of the mammary glands, which are finally prepared for feeding during pregnancy. The shape of the nipple can create problems at the beginning of feeding, but over time these features get used to and the difficulties are overcome.

MYTH:

Failure to feed the first child precludes the possibility of breastfeeding.

REALITY:

Much of the failure to feed is due to the correct sucking technique of the baby. Usually, women have more milk after their second pregnancy, and if the baby suckles well, everything may be fine.

MYTH:

A woman can always determine breast fullness by her feelings, there is no milk in soft breasts.

REALITY:

The feeling of fullness in the breasts always disappears in the normal way by the second or third month of feeding, the breasts become "empty" and decrease in size. This does not mean that there is not enough milk. Just in case, you can track how much the baby gains weight per week. If it adds well, at least 150 grams per week, there is no reason to worry.

MYTH:

Breast milk can be controlled by pumping.

REALITY:

Normal breastfeeding does not require pumping at all. It is absolutely not suitable for self-control, because the child always stimulates the breast more than any device.

MYTH:

In hot weather, give your baby water.

REALITY:

In the first six months of life, a baby does not need anything but breast milk, and he does not need water. Breast milk always contains a sufficient amount of liquid that is well absorbed by the baby. If it is hot, the baby will usually ask for the breast more often, thereby covering the increased need for fluids. Giving your baby extra drinks all the time can interfere with the flow of breastfeeding because the baby's stomach simply won't fit the right amount of breast milk. If the child is offered additional drinks for a long time, this can lead to a decrease in the baby's appetite.

MYTH:

The quantity and quality of breast milk can be improved by eating (halva) or drinking (tea with milk).

REALITY:

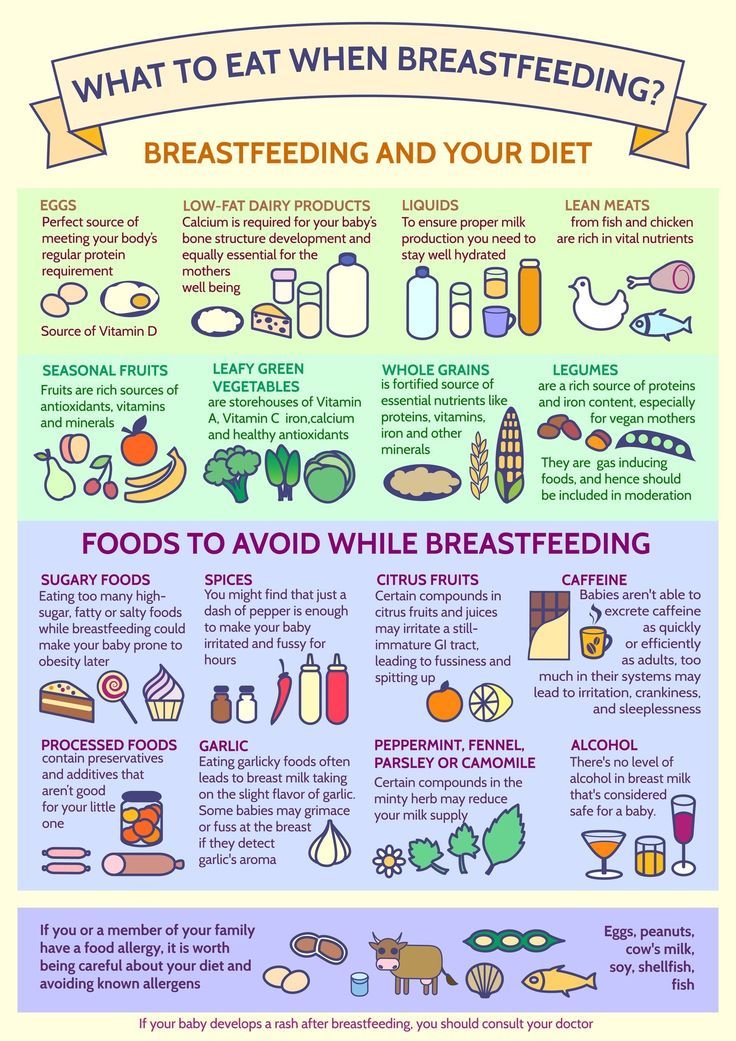

The quality of breast milk is practically independent of the mother's diet. All the components necessary for the child - water, proteins, carbohydrates and fats - are present in breast milk even when the mother's nutrition is limited. Only the content of water-soluble vitamins (vitamin C and B vitamins) is directly dependent on the mother's diet. Therefore, vegan mothers should make sure that they are getting enough vitamins D and B12, iron, calcium and zinc during breastfeeding. The amount of breast milk directly depends on the needs of the child, and only as much breast milk is produced as needed at the moment. The baby should ask for the breast at least eight times a day and gain an average of 600-800 grams in weight every month. In this case, his diet is all right. More frequent feedings increase the amount and fat content of milk.

MYTH:

Breastfeeding spoils the shape of the breast.

REALITY:

Breasts enlarge even during pregnancy, and in order for their shape not to change, you should wear the right size, well-supporting bra. In the first days after childbirth, the breast increases slightly, then, by about the second month, it decreases and becomes “soft”. The duration of feeding does not affect the shape of the breast.