Can i add salt to my baby food

How Much Should They Eat?

If you’re a new parent, you may be wondering how much salt is OK to include in your baby’s diet.

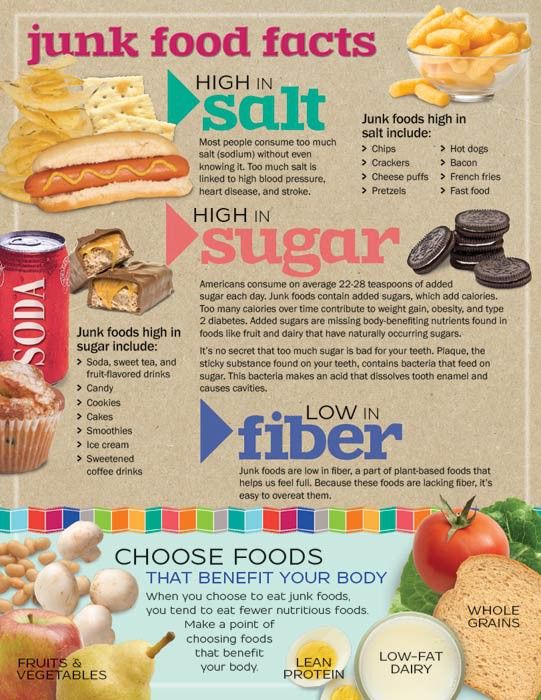

While salt is a compound that all humans need in their diets, babies shouldn’t get too much of it because their developing kidneys aren’t yet able to process large amounts of it.

Giving your baby too much salt over time may cause health problems, such as high blood pressure. In extreme and rare cases, a baby that’s had a large amount of salt may even end up in the emergency room.

Too much salt during infancy and childhood may also promote a lifelong preference for salty foods.

This article explains what you need to know about salt and babies, including how much salt is safe, and how to tell whether your baby has had too much salt.

You may add salt to your baby’s food in hopes that it’ll improve the taste and encourage your baby to eat.

If you use a baby-led weaning approach to feeding your baby, you may end up serving your baby foods containing more salt simply because you’re serving them the saltier foods you eat as an adult (1, 2).

However, babies who get too much salt through their diets can run into a few issues.

A baby’s kidneys are still immature, and they aren’t able to filter out excess salt as efficiently as adult kidneys. As a result, a diet that’s too rich in salt may damage a baby’s kidneys. A salt-rich diet may also affect a baby’s long-term health and taste preferences (3, 4).

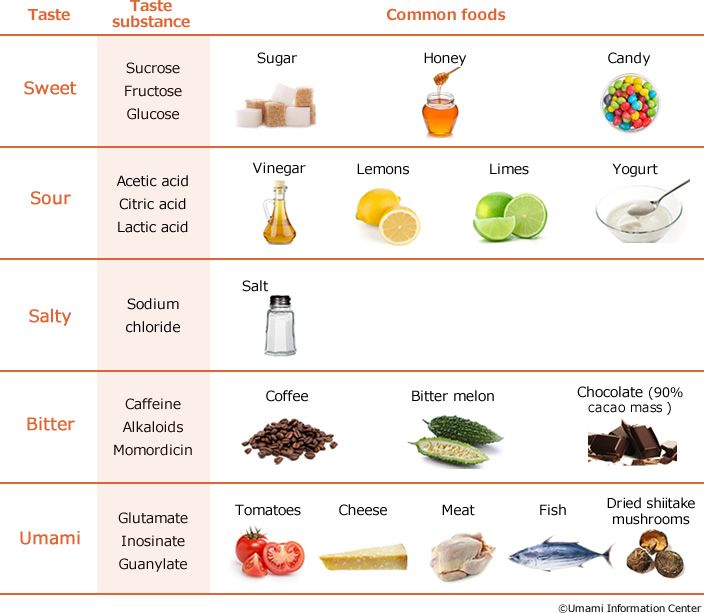

Babies are born with a natural preference for sweet, salty, and umami-tasting foods (1, 4, 5).

Repeatedly being offered salty foods may reinforce this natural taste preference, possibly causing your child to prefer salty foods over those that are naturally less salty.

Processed foods, which tend to be salty but not typically rich in nutrients, may be preferred over whole foods with naturally lower salt contents, such as vegetables (4, 6, 7, 8, 9).

Finally, salt-rich diets may cause your baby’s blood pressure to rise. Research suggests that the blood-pressure-raising effect of salt may be stronger in babies than it is in adults (3).

As a result, babies fed a salt-rich diet tend to have higher blood pressure levels during childhood and adolescence, which may increase their risk of heart disease later in life (10, 11).

In extreme cases, very high intakes of salt can require emergency medical care, and in some cases, even lead to death. However, this is rare and usually results from a baby accidentally eating a quantity of salt much larger than parents would normally add to foods (12).

SummaryToo much salt can damage a baby’s kidneys, increase their blood pressure, and possibly raise their risk of heart disease later in life. A salt-rich diet may also cause your child to develop a lasting preference for salty foods.

Sodium, the main component in table salt, is an essential nutrient. Everyone, including babies, need small amounts of it to function properly.

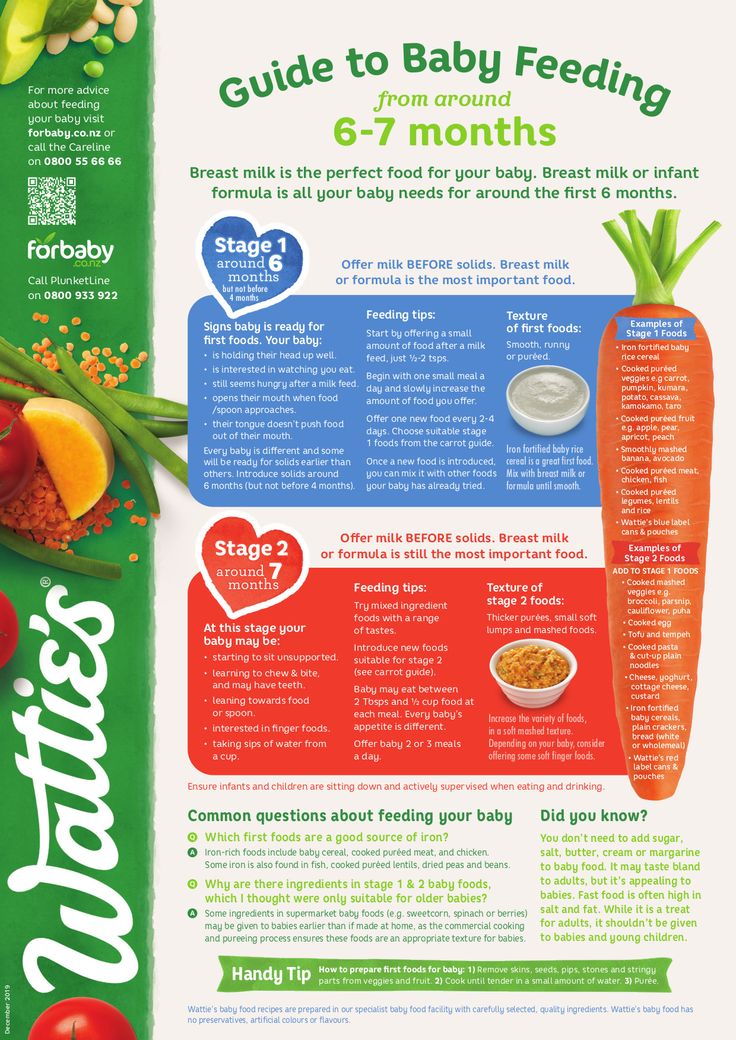

Young babies under 6 months of age meet their daily sodium requirements from breast milk and formula alone.

Those 7–12-months-old are able to meet their needs from breastmilk or formula and the small amounts of sodium naturally present in unprocessed complementary foods.

As such, experts recommend that you don’t add salt to your baby’s food during their first 12 months (2, 4, 5).

Having an occasional meal with salt added is OK. You may sometimes feed your baby some packaged or processed foods with salt added or let them try a meal from your plate. That said, overall, try not to add salt to the foods you prepare for your baby.

After 1 year of age, recommendations vary slightly. For instance, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) considers 1,100 mg of sodium per day — about half a teaspoon (2.8 grams) of table salt — safe and adequate for children of 1–3 years (13).

In the United States, recommendations for the same age group average 800 mg of sodium per day. That’s about 0.4 teaspoons (2 grams) of table salt per day (14).

SummaryBabies under 12 months should not get any additional salt through their diet.

Intakes between 0.4–0.5 teaspoons of salt appear safe in children up to 4 years old.

If your baby eats a meal that’s too salty, they may seem thirstier than usual. Typically, you won’t notice the effects of a high salt diet immediately, but rather over time.

In extremely rare cases, a baby that’s eaten too much salt can develop hypernatremia — a condition in which there’s too much sodium circulating in the blood.

If left untreated, hypernatremia can cause babies to progress from feeling irritable and agitated to drowsy, lethargic, and eventually unresponsive after some time. In severe cases, hypernatremia can result in coma and even death (15).

Milder forms of hypernatremia can be more difficult to spot in babies. Signs that your baby may have a mild form of hypernatremia include extreme thirst and a doughy or velvety texture to the skin.

Very young babies may start crying in a high pitched fashion if they’ve accidentally eaten too much salt.

If you think that your baby may have gotten into too much salt or is beginning to show signs of hypernatremia, call your pediatrician.

SummaryIf a baby has a salty meal occasionally, you may notice they are thirsty. In extremely rare cases, babies who have ingested large amounts of salt may develop hypernatremia and require medical attention.

As a parent, you can limit the amount of salt your baby eats in several ways.

Most baby food purées may contain small amounts of naturally occurring sodium from the foods they are made with but very little, if any, added salt. If your baby is currently eating them exclusively, they’re unlikely to ingest too much salt.

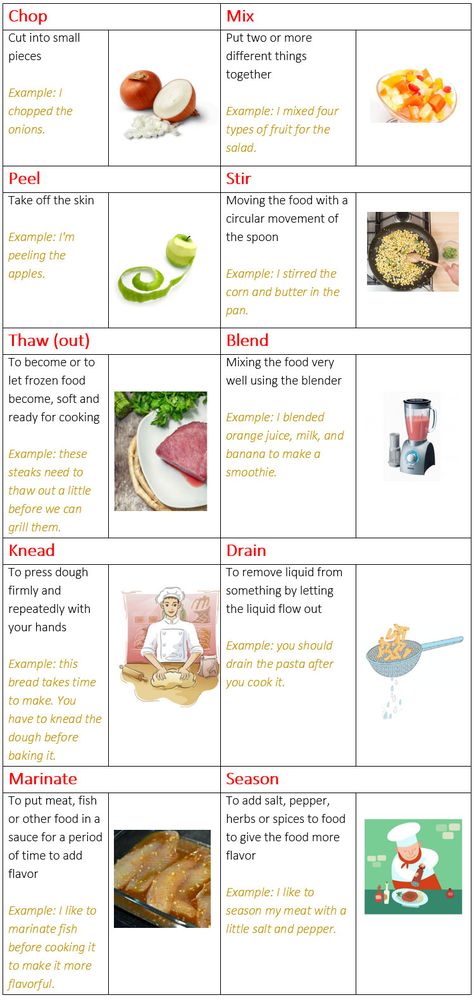

If you make your own baby food, skip adding salt, choose fresh foods, and check labels on frozen or canned vegetables and fruits to find lower sodium options.

Also, remember to rinse canned foods, such as beans, lentils, peas, and vegetables, before adding them to purées or meals. Doing so helps reduce their sodium content (16).

Doing so helps reduce their sodium content (16).

If you’re doing baby-led weaning, you can set aside a portion of meals for baby before adding salt or make family meals with spices and herbs instead of salt.

Check the sodium content of foods you frequently buy, such as bread, cereal, and sauces. Lower sodium versions are available for most packaged foods, and comparing labels can help you find a brand with less salt added.

Frozen meals, as well as takeout or restaurant foods, are generally higher in salt. Occasionally, it’s fine for baby to have these meals, but when dining out, a lower salt alternative would be to bring a few foods from home for your baby.

SummaryYou can minimize the amount of sodium your baby eats by offering them foods without added salt. Replacing pantry foods like bread and sauces with low sodium alternatives can also help.

Babies need small amounts of salt in their diet. However, their bodies can’t handle large amounts. Babies fed too much salt may be at risk of kidney damage, high blood pressure, and possibly even an increased risk of heart disease.

Babies fed too much salt may be at risk of kidney damage, high blood pressure, and possibly even an increased risk of heart disease.

Moreover, a salt-rich diet may cause babies to develop a lifelong preference for salty foods, in turn, possibly lowering the overall quality of their diet.

Try not to add salt to your baby’s foods when they are under 12 months. After 1 year, you can include a small amount of salt in your child’s diet.

Just one thing

When cooking a family-style meal, get into the habit of adding salt near the end of cooking. This way, you can reserve a no-salt-added portion for your baby.

Don’t Add Salt to Baby Food: The Surprisingly Weak Evidence for Infant Sodium Requirements

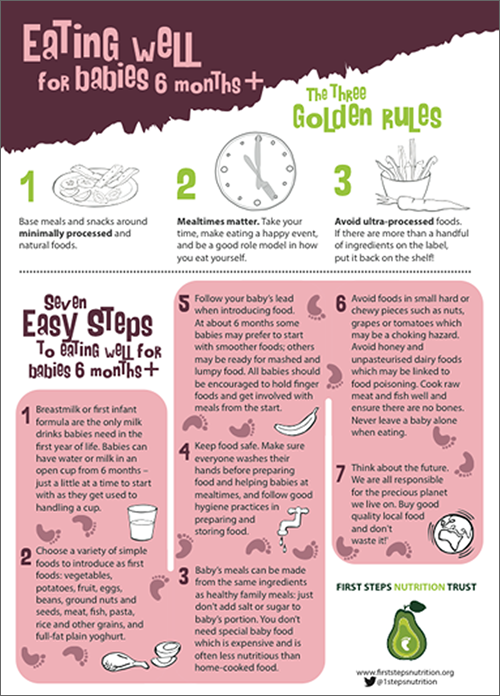

When my readers asked me to write about starting solids, I wanted to focus on nutrient dense real food for babies wherein I explain the rationale for starting with minimally processed real food. You can read that in-depth article here.

As I started writing, I realized there was a big nutritional elephant in the room that I couldn’t ignore: SALT.

Virtually every resource out there on infant nutrition warns against cooking with salt or adding any salt to baby food. The rationale given ranges from “it could harm their developing kidneys” to “it could predispose them to high blood pressure” to “it will set them up to prefer salty foods later in life.”

Some of the warnings you hear sound dire, like the section on foods to avoid in The Baby Led Weaning Cookbook, which reads as follows:

“A baby’s immature kidneys can’t cope with too much sodium, and can make them very ill, so it’s important to avoid it as much as possible. A high sodium diet early on may also make babies more prone to high blood pressure later in life. Salt shouldn’t be added to any food that is going to be offered to your baby.”

If you don’t already have anxiety about starting solids with your baby, reading warnings like this will surely change that.

Don’t Add Salt to Baby Food: The Surprisingly Weak Evidence for Infant Sodium RequirementsI’ll admit that when I started solids with my son as a baby (who, at the time of writing, is a perfectly healthy toddler), I didn’t strictly avoid salt in his foods. The rationale didn’t make sense to me, especially in light of the myths about salt for adults that are perpetuated in outdated dietary guidelines. It was also a matter of convenience, since he mostly ate the same foods that we ate for meals (aka baby led weaning).

The rationale didn’t make sense to me, especially in light of the myths about salt for adults that are perpetuated in outdated dietary guidelines. It was also a matter of convenience, since he mostly ate the same foods that we ate for meals (aka baby led weaning).

[Note: I can already feel the disdain of pediatric dietitians as they read that paragraph. Please, keep an open mind and keep reading!]

This round as my daughter starts on solid foods, I’ve decided to take a closer look at the evidence behind the low salt recommendation for babies. Maybe I should have been more careful with salt with my son? Or maybe how I handled that was just fine.

I wanted answers.

Why Do Conventional Recommendations Limit Sodium for Babies?Good question! After asking half a dozen experts in pediatric nutrition and baby led weaning, mostly fellow dietitians, I was left with more questions than answers about sodium intake and babies.

The most common reason given for avoiding salt in baby food was the argument that their kidneys are too immature to process excess salt, but none of them were able to point me to peer reviewed literature on the topic.

That meant I needed to do it. I scoured the literature for weeks and ultimately came up empty handed. Most of what I found was in relation to preterm infants needing increased amounts of sodium, not less. But what about term infants who are now ~6 months old and starting solids? Nothing.

I then came across a summary from a group of researchers who were tasked with examining the nutrition guidelines for accuracy and identifying areas where the evidence was weak. This is where I started finding answers.

To my surprise, the infant guidelines on sodium are a massive “guesstimate.”

How the Sodium Limit for Babies was SetThe guidelines on sodium for infants are what’s called an “adequate intake” or AI. The guidelines opt for an adequate intake when there is not enough evidence to set an estimated average requirement (or EAR).

In a nutshell, an adequate intake level is the daily average nutrient intake based on estimates of what a healthy group of people consume in their diet. It is assumed that because this group of people is generally healthy, then their intake of that particular nutrient (in this case, salt) must be adequate.

It is assumed that because this group of people is generally healthy, then their intake of that particular nutrient (in this case, salt) must be adequate.

In other words:

“For sodium, “nutrient adequacy” refers to the sodium intake level at which one could consume a diet that basically meets all the recommended dietary intakes for other nutrients.” — Institute of Medicine, 2007

For this reason, when it comes to infants, the default food source is breast milk. Thus, the adequate intake level is set based on average breast milk concentrations of sodium. However, this isn’t a perfect science, since breast milk nutrient levels vary significantly, as I teach in extensive detail in my continuing education webinar: Nutrients for Breastfeeding: Effects of Maternal Intake on the Nutrient Content of Breast Milk.

Researchers explain how the AI is set for infants less than 6 months of age as well as their limitations:

“The AI for all the nutrients for infants in the first six months of age was obtained by multiplying the average daily volume of breast milk (780 mL) times the concentration of the nutrient in breast milk.

One serious problem is the accuracy of the data on human milk composition. The reported nutrient values for human milk vary widely among and within different studies. Reasons include small numbers of subjects, changes in composition over the course of feeding and over the course of lactation, improper sampling, effects of supplement use and food fortification on milk composition, and analytical problems.” — Institute of Medicine, 2007

Furthermore, researchers explain how the AI is set for older infants (7-12 months) as well as their limitations:

For infants 6 months and older, who are assumed to be eating breast milk plus solid food, the AI was obtained by “adding the estimated mean intake of the nutrient from solid food to the amount of that nutrient provided by 600 mL of breast milk. Dietary data on nutrients from solid foods were unavailable for many of the nutrients. Thus, in many cases, the AI was obtained by extrapolating up from the younger infants and/or down from older age groups.

” — Institute of Medicine, 2007

As you can see, this presents a fundamental flaw in the basis for the AI.

Adequate intake is really just average intake. And average intake is a moving target when breast milk sodium levels vary widely as does the amount of sodium in solid food.

Not to mention, not all infants consume the same amount of breast milk. Unless a mother is exclusively pumping, it’s actually impossible to quantify the exact amount of breast milk consumed by an infant. Moreover, intake varies on a day-to-day basis.

Dr. Allen explains how this is pertinent to many nutrients, not just sodium, in this quote:

“A few examples illustrate the nature and extent of the limitations of data on human milk composition. For iron, the average concentration is said to be 0.35 mg/L, but the literature provides values ranging from 0.20 to 0.88 mg/L. The 0.35-mg value is approximately in the middle of that range. One new study from Sweden (Domellof et al.

, 2004), which has a large sample size relative to other studies, reports a value of 0.29 mg of iron per liter of breast milk, which, in practice, is considerably lower than the 0.35-mg value in current use. For vitamin A, an average of 485 µg/L is the value chosen, but the values considered ranged from 314 µg/L to 640 µg/L. The situation is similar for vitamin B12, for which a value of 0.42 µg/L was chosen. The lowest reported value, 0.31 µg/L, was from vegans; the highest value, 0.91 µg/L, was from Brazilian women who received prenatal supplements.”

It’s virtually impossible to guarantee that an infant is receiving a specific quantity of almost any nutrient (especially vitamins and minerals) from breast milk without quantifying the levels in every last drop of breast milk that the baby consumes. This is obviously impractical!

What’s even more perplexing to me is that even though the dietary guidelines committee was presented with this information on the variable levels of nutrients in breast milk all the way back in 2007, a new committee in 2019 (which, sadly, did not include Dr. Allen, who raised the above valid questions) decided on an even lower sodium target for infants aged 0-6 months.

Allen, who raised the above valid questions) decided on an even lower sodium target for infants aged 0-6 months.

In a summary from the 2019 Dietary Reference Intakes, they state:

“The sodium AI for infants 7–12 months of age is based on estimated sodium intake from breast milk and complementary foods. The mean sodium concentration in breast milk for this age group was estimated to be 110 mg/L (5 mmol/L). Assuming an average breast milk consumption of 600 mL/d, approximately 70 mg/d (3 mmol/d) sodium is consumed from breast milk. Sodium intake from complementary foods was estimated to be 300 mg/d (13 mmol/d). The sodium AI for infants 7–12 months is therefore established at 370 mg/d (16 mmol/d).”

This document cited ZERO research connecting sodium intake to adverse outcomes in infants. NONE. They also failed to address the concerns raised by Dr. Allen of varying sodium content in breast milk from back in 2007.

You’ve gotta love how the language used in these guidelines sounds like there is absolutely, positively no room for error. Riiiiiiiiight.

Riiiiiiiiight.

I decided to dig into the literature to see what constitutes an average level of sodium in mature breast milk.

How Much Sodium is in Breast Milk? Does the Sodium Level in Breast Milk Vary?As stated above, the official adequate intake level (AI) of sodium for infants is based on the average sodium levels in breast milk. This is assumed to be 110 mg/L for infants 7-12 months old.

Much as Dr. Allen alluded to, I came across research showing a WIDE variation in sodium levels in breast milk.

In a study of 197 rural Gambian women, “substantial variation in breast milk sodium content” between women was identified, although it tended to reduce over time becoming lower in sodium and less variable in sodium content as the infants reached 6 months of age. Nonetheless, breast milk sodium levels were 163 mg/L on average in women with infants aged 6 months. That’s 48% higher than the AI.

In a study of Turkish women, breast milk collected at 42 days postpartum ranged from 45 to 1703 mg/L (average 330 mg/L) of sodium. The average is 3x higher than the average level used to set the US guidelines, and clearly, some women have breast milk sodium concentrations substantially higher than that (15.5x higher!). Breast milk is typically higher in sodium in early postpartum, however, most research assumes that sodium concentrations drop to a relatively stable level after approximately 2 weeks post birth. This study brings this assumption into question. The study authors note “The high sodium concentrations of this study may be due to dietary habits of Turkish women with a consumption of salt; 14 g/day.” For reference, this is more salt than the average American adult consumes.

The average is 3x higher than the average level used to set the US guidelines, and clearly, some women have breast milk sodium concentrations substantially higher than that (15.5x higher!). Breast milk is typically higher in sodium in early postpartum, however, most research assumes that sodium concentrations drop to a relatively stable level after approximately 2 weeks post birth. This study brings this assumption into question. The study authors note “The high sodium concentrations of this study may be due to dietary habits of Turkish women with a consumption of salt; 14 g/day.” For reference, this is more salt than the average American adult consumes.

In a study of American women, breast milk sodium levels averaged 212 mg/L at 3 weeks, 145 mg/L at 3 months, and 138 mg/L at 6 months postpartum. The 6 month average is 25% higher than the established AI. The study authors note that “It is clear that the milk composition is continuously in transition and that the milk of each woman has a characteristic ionic composition. ”

”

In a study of Iranian women, breast milk sodium levels were measured at 1-2 months, 6-7 months, and 12 months postpartum. At 1-2 months, levels averaged 122 mg/L. At 6-7 months, 155 mg/L. And at 12 months, 196 mg/L. What’s interesting about this data is that it’s opposite of the accepted norm for changes in breast milk sodium concentrations. Rather than decreasing over time, they increased. Also, the standard deviation in breast milk sodium concentration did not stabilize over time. It varied by +/-92-95 mg/L in 1-2 and 6-7 month olds, but varied by +/-150 mg/L in milk for 12 month olds. This is opposite of what’s been observed in the milk of American women.

In a study of Japanese women, the average level of sodium in breast milk in those with infants aged 6-12 months was 116 +/- 6 mg/L. Of all studies I found, this was the closest to the US adequate intake level with the least inter-individual variability in sodium levels.

Overall, sodium levels in breast milk vary widely, so it would make much more sense to have an adequate intake range versus a single number.

Some research even suggests that there might be differences in sodium concentrations of milk based on location or ethnicity of the mother:

“Our review of other studies examining breast milk sodium suggests that there may be geographical and/or ethnic differences in breast milk sodium concentration. For all of these reasons, we suggest that it is not appropriate to use a standardised measure of breast milk sodium content when direct measurement is possible.” — Paediatric And Perinatal Epidemiology, 2010

Variable sodium concentrations could also be due to differences in sampling method, analytic techniques, and other factors, as explained in this study:

“There exists some controversy in data for concentrations of trace elements in breast milk because they are expected to vary widely from country to country. The variations of trace element concentrations in previous studies may be due to different analytical techniques, sampling time and method, the stage of lactation, and socioeconomic status of subjects.

” — Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, 2018

All this to say, the AI for infant sodium “requirements” is FAR from set in stone. It’s a ballpark figure and the milk of many women will have sodium levels outside of this ballpark, maybe even in another state!

We can’t use a single arbitrary standard for breast milk sodium levels to set infant sodium requirements. This is bad science.

If we don’t actually know the sodium intake of infants, how can we estimate an adequate intake level?

The answer is: we can’t.

Onto the next argument against salt and infants…

Does High Sodium Intake Harm Infant Kidneys?I dug and dug and dug for studies on infant kidney function being harmed by excess sodium. I came up empty handed.

In neonatal medicine, it’s known that neonatal kidneys are less able to handle high concentrations of sodium, but it’s questionable if this poses any realistic “threat” to them.

It appears that the original fears surrounding sodium and infants dates back to a study from the 1940s, where infants (and adults) were given an IV solution with 40% sodium chloride and then researchers monitored urine output. Infants were not able to excrete the sodium load in their urine to the same degree as adults. However, later analyses of this research explains why these findings aren’t necessarily of use: “Of interest is that sodium was not measured during those studies, but the authors’ conclusions about sodium excretion were extrapolated from measurements of urine volume.”

In other words, this data means nothing.

Furthermore, relying on urine volume as a proxy of kidney function in infants is also invalid, as the rate of adequate urine flow for infants is also a giant guess. The study explains:

“In the absence of a reliable and easily interpretable measurement of GFR [glomerular filtration rate, a measurement of kidney function] in the neonate, many clinicians have resorted to estimating renal function by urine volume.

An arbitrarily chosen urine flow rate equal to or more than 1 ml/h per kilogram has been accepted widely as “adequate renal function”.”

Let me emphasize from the above quote: arbitrarily chosen urine flow rate. We really don’t know for sure what urine flow rate in infants is physiologically normal or not.

Even if researchers could identify a valid or “ideal” urine flow rate for infants, how would you measure this accurately? A 2008 paper explains this quandary:

“The gold standard for the measurement of sodium is 24-h urinary sodium. However, this method is difficult to implement in infants (requires urine extraction from diapers) and is not feasible in population studies.”

So we’ve established that sodium output via an infant’s urine is impractical (impossible?) to measure and that it’s really hard to identify a clear measure of kidney function in infants.

The fear remains that if baby ingests too much salt, baby’s kidneys could theoretically be unable to flush out high amounts of sodium and could develop high blood sodium levels as a result. Ok, I can understand this fear, but do we see high blood sodium levels often in infants or is this all theoretical? Public health officials often say that infants and children consume too much salt, but is there actual evidence of harm?

Ok, I can understand this fear, but do we see high blood sodium levels often in infants or is this all theoretical? Public health officials often say that infants and children consume too much salt, but is there actual evidence of harm?

Interestingly, as you dig further into the literature on this topic, low sodium levels (called hyponatremia) are far more common and serious threat than high blood sodium levels (called hypernatremia) in infants.

Here’s a snippet from one study explaining this observation:

“Clinical experience with newborn infants would suggest that hyponatremia and salt wasting are observed more frequently than hypernatremia and salt retention. Both the inability to excrete a sodium load and the capacity of the kidney to conserve sodium in the face of hyponatremia have been used as arguments to propose that the newborn kidney is functionally immature. What these two opposing views suggest, however, is that neither is, by itself, a marker of tubular maturation.

”

Lastly, it’s very hard to find data on sodium balance at different stages of early infancy and at the age where solid foods would be introduced. However, I found data that suggested as infants approach one year of age, their kidney function is similar to adults.

I also found data suggesting healthy infant kidneys are able to handle and excrete higher sodium loads starting at around 4 months of age.

Perhaps by the time baby is introduced to solid foods, their kidneys are also mature enough to handle a little more salt? Maybe. It’s certainly food for thought.

Ultimately, the suggestion that infant kidneys are “too immature” to excrete sodium does not appear to be a solid argument against the inclusion of small amounts of salt in baby food.

This study explains,

“Impaired concentrating ability of the neonatal kidney is probably of no clinical significance in all but the most extreme circumstances and is not a major factor in an infant becoming dehydrated, developing hypernatremia or being at greater risk of acute renal injury.

”

The cases of hypernatremia I identified most often in the literature were due to extreme dehydration (typically due to inadequate consumption of breast milk, meaning inadequate fluids, not excessive salt intake). Excessive fluid losses can also occur from GI infections that lead to diarrhea or vomiting.

A review of hypernatremia cases in the UK from 1998 found an incidence of only 2.5 cases per 10,000 live births in exclusively breastfed infants. There were 8 cases in the UK that year and “The sole explanation for hypernatraemia was unsuccessful breastfeeding in all cases.”

They go on to explain:

“The poor satiety achieved by some of these infants, their poor urine output, and poor stool output all suggest that the problem is water deprivation, with secondary accumulation of sodium in an attempt to maintain circulating volume.”

However, I also found one case study on hypernatremia in an infant resulting from improperly manufactured infant formula, which mistakenly contained 8x the usual level of sodium.

I found ZERO case studies on “excessive” sodium consumption from complementary food leading to hypernatremia or kidney damage. None.

Moreover, almost all hypernatremia cases documented in the literature (dating back to the 1970s) are in young infants, usually around 10 days of age (with a range of 3-21 days).

The hypothetical fears that small amounts of sodium in infant foods will harm a baby’s kidneys at age 6 months of age or beyond seem to be exactly that: hypothetical.

Does Salt Intake in Infancy Predispose People to High Blood Pressure as Adults?The notion that salt intake in infancy might lead to high blood pressure in adulthood has been around for decades. It’s also been debated for decades.

A Little History on Salt & Baby Food

Public concern over sodium intake and infants appears to date back to 1963, when it was questioned whether prepared infant foods might be providing more sodium than necessary (although there were no guidelines on sodium intake for infants yet)—and that high salt intake could predispose infants to hypertension as adults.

At the time, the evidence suggesting this connection was exclusively epidemiological studies and animal studies. However, neither of these two bodies of evidence can show cause and effect in humans. We know that genetic and nutritional factors, as well as many others, play into the predisposition and development of high blood pressure.

By 1970, food manufacturers were recommended to cut back on sodium in baby food and by 1977, added salt was completely eliminated from prepared infant foods.

Sodium intake in infants from the years 1969 compared to 1979 dropped by 68% for the average 6 month old. All of these changes to the baby food industry were spurred by pure conjecture on the perceived harms of sodium, not solid science.

The Studies on Infant Sodium Intake & Blood PressureIn the early 1980s, a randomized trial in the Netherlands of over 400 newborn infants looked at the effect of a low or normal sodium diet on blood pressure during the first 6 months of life. Families were provided with either a low sodium or normal sodium formula (and were also permitted to breastfeed). The normal sodium formula was equivalent to formulas available in the Netherlands at the time, while the low sodium formula had only ⅓ of the usual quantity of sodium. Parents were instructed to start solid foods, all of which were provided by the study, at 13 weeks of age (~3 months old). When the trial ended at 25 weeks of age (~6 months), systolic blood pressure in the low sodium group was 2.1 mm Hg lower than in the control group.

Families were provided with either a low sodium or normal sodium formula (and were also permitted to breastfeed). The normal sodium formula was equivalent to formulas available in the Netherlands at the time, while the low sodium formula had only ⅓ of the usual quantity of sodium. Parents were instructed to start solid foods, all of which were provided by the study, at 13 weeks of age (~3 months old). When the trial ended at 25 weeks of age (~6 months), systolic blood pressure in the low sodium group was 2.1 mm Hg lower than in the control group.

To date, this is still one of the most widely cited studies that people use to defend low salt guidelines for infants. What no one seems to comment on is that 0-6 months of life is when—assuming people are following the current WHO guidelines—infants should be receiving nothing other than breast milk or formula… so how does this translate to whether or not people include salt in solid foods once introduced at 6+ months of age? Good question.

Moreover, a difference of 2.1 mm Hg is not that much. With repeat measurements of blood pressure, whether or not I’m stressed, or even deep breathing during the test, I can easily shift my blood pressure a few points, but I digress…

In the 1990s, another research team examined blood pressure in a subset of participants from the aforementioned Dutch study at age 15 years old. They found lower blood pressure, on average, in the teens who had received the low salt intervention at 0-6 months old. Unfortunately, since this study did not include all original participants, the two groups had widely varying baseline characteristics, as explained in the following quote. This is a major limitation to these findings.

The authors note:

“Whereas the study groups in the original trial were similar with regard to birth length and weight, maternal systolic BP, and maternal educational level, these variables differed significantly between the sodium groups in the follow-up study.

”

In short, the blood pressure findings in these teens could have been related to sodium intake as infants from 0-6 months of age or could have been related to other predisposing factors. That is the trouble with these types of studies. They only show correlation, but not causation.

A separate study provided infants with either low sodium intake or high sodium intake (equivalent to “a salt intake representing the 99th percentile of sodium intake by U.S. infants in 1969”) for 5 months straight (from ages 3 to 8 months). Blood pressure was measured in infancy and again at 8 years of age. As you can recall, sodium intake by infants in 1969 was relatively high because baby food manufacturers still included salt.

This study found ZERO correlation between salt intake during infancy and blood pressure in infancy and later childhood. Of note, the high sodium group consumed 5x more sodium than the control diet.

How did their bodies cope with all this salt, you ask? Just like adults. They peed it out.

They peed it out.

“Significantly increased sodium and potassium excretion was noted on the salted diet and significantly increased aldosterone excretion was noted on the unsalted diet. [Aldosterone is a hormone secreted to prevent sodium losses.] A 6% expansion in extracellular fluid volume for the high sodium group was statistically significant but was not correlated with blood pressure or urine volume and did not result in edema or increased weight.”

A fairly large 2008 prospective cohort study from the UK looked at sodium intake in infancy (at 4 and 8 months) and blood pressure at 7 years of age. Ultimately, they found that sodium intake at 4 months of age might be of concern. However, the infants in this study were not consuming excess sodium at this age:

“We found some evidence that greater sodium intake in infancy is associated with elevated BP in later life; however, this was found for sodium intake at 4 months only despite almost all infants at this age consuming below the maximum recommended intake.Further studies are required to confirm this finding before one could conclude that infancy is a sensitive period with respect to the effect of dietary sodium intake on later BP.”

Interestingly, in this study, neither sodium intake at 8 months nor at 7 years was associated with blood pressure at 7 years. This is perplexing, given that sodium intakes at those ages were often above recommended intakes.

Even the study authors caution that these findings are questionable:

“The association between sodium intake at 4 months and later SBP [systolic blood pressure], found in this study, may simply be a chance finding.”

This study also had a major flaw in that it assumed breast milk sodium concentrations to be consistent, and as I showed earlier in this post, that’s faulty logic.

They further go on to explain that the young age of the infants may explain the findings:

“It is also possible that early infancy may represent a sensitive period in relation to effects of sodium on later BP since, before the age of 4 months, infants are less efficient at excreting excess sodium and healthy infants only begin to excrete an excessive sodium load at around 4 months.

”

In other words, it’s possible that the very early introduction of solid foods to young babies is the problem. After 4 months, their kidneys are mature enough to excrete more sodium than they are prior to this age. For those who wait to introduce solids until 6 months, hypervigilance about salt might not be as much of a concern.

What’s interesting is that some of the early data from the 1960s suggesting that salt was harmful to infants actually comes from infants introduced to solids at an extremely early age, as young as 1-3 months. This is indeed when kidneys are not mature and also when their digestive system is not ready for food other than breast milk or formula.

What foods were these infants offered, you ask? Typically canned pureed vegetables, canned pureed meats, evaporated milk, and “precooked” cereals (aka instant cereals) — all of which are often very high in sodium.

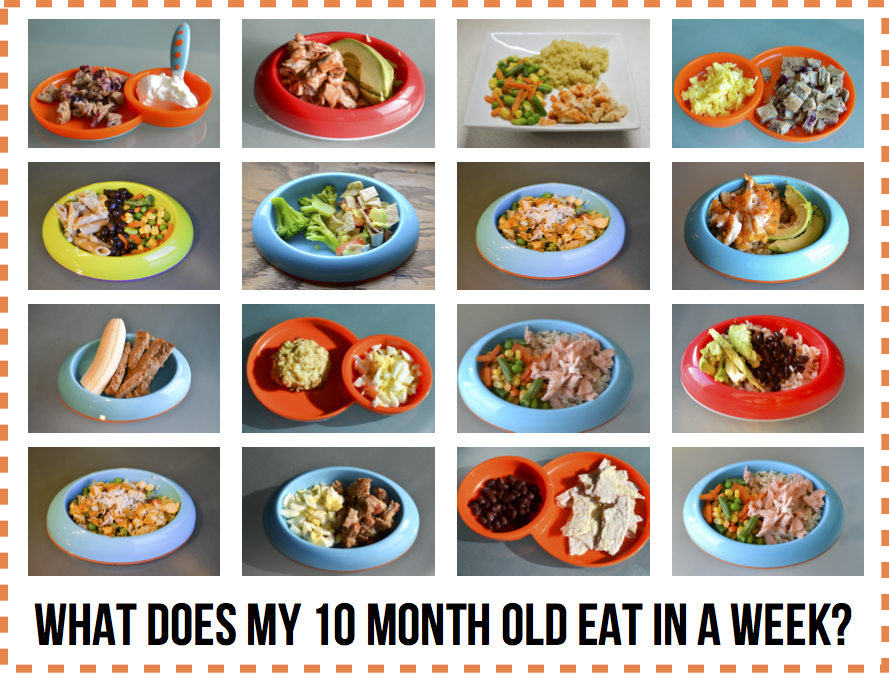

The following image is from a 1963 study showing how much salt was in these early processed baby foods.

No doubt these babies were:

a) way too young to be given solids

b) absolutely exposed to excess sodium (some estimate that sodium intake of infants in this era averaged 2300mg per day!)

As always, context matters.

Processed and canned foods have always been—and continue to be—excessively high in sodium. Don’t give these foods to babies! We might not have great evidence for the sodium guidelines for infants, but it’s safe to say they don’t need as much as a full grown adult.

In addition, the last 50+ years of evidence support waiting until babies are at least 4 months old (preferably 6 months) before introducing solid foods. If you choose to go against these suggestions and introduce solids early, absolutely DO NOT add salt to baby food.

If you choose to heed the recommendation of the World Health Organization and start introducing solids around 6 months (which I agree with), the evidence for completely restricting sodium as a means of avoiding future hypertension is simply not there.

The available studies primarily involve introduction to solids far too early, have significant flaws in methodology, and DO NOT follow the infants all the way into adulthood where correlation (let alone causation) could be implied.

The final warning you hear about salt for babies is that introducing them to salty foods will preprogram them to prefer salty foods later in life. Much like the fears around hypertension, this remains unproven and hotly debated.

In the previous section, I referenced a study that provided a group of infants to a high sodium intake at ages 3-8 months and another group to a low sodium control diet. The high sodium diet provided 5x more sodium than the control diet. The study followed infants until 8 years of age and found “no indication that the salted foods imprinted a preference for salt at 8 years.”

In contrast to this study, another found that infants who showed a preference for salt water in infancy were more likely to have a higher salt intake later in toddlerhood. However, this widely publicized study had some details left out of the press releases. Only infants who had been introduced to starchy table foods prior to 6 months showed a higher affinity to salt. These children were “more likely to lick salt from the surface of foods at preschool age.” This raises the question whether it’s a preference for salt or refined carbohydrates at play.

However, this widely publicized study had some details left out of the press releases. Only infants who had been introduced to starchy table foods prior to 6 months showed a higher affinity to salt. These children were “more likely to lick salt from the surface of foods at preschool age.” This raises the question whether it’s a preference for salt or refined carbohydrates at play.

The most interesting finding from my literature review was that there’s research to suggest that infants who were exposed to sodium/electrolyte/fluid imbalance in utero and in early life may prefer salt more as infants and young children.

This has been studied in the context of children born to mothers who experienced severe morning sickness, who were fed formula that was too low in sodium, who experienced excessive vomiting or diarrhea in infancy, or those born premature who experienced clinical hyponatremia early in life. In all of these scenarios, higher salt intake is observed in childhood.

As one study explains,

“The source of individual variation in salt appetite and why many people ingest an excess of salt are not known. Early development is considered to be a crucial period for establishing individuality in behavior and may similarly determine individual differences in salt preference.” — American Journal of Physiology, 2007

Specifically in children that were born with a low birth weight, those with the lowest blood sodium levels at birth are noted to have the highest intake of salt in childhood and adolescence.

One study explains:

“The relationship of NLS [neonatal lowest serum sodium level] and dietary sodium intake was found in both boys and girls and in both Arab and Jewish children, despite marked ethnic differences in dietary sources of sodium. Hence, low NLS predicts increased intake of dietary sodium in low birth weight children some 8–15 yr later. Taken together with other recent evidence, it is now clear that perinatal sodium loss, from a variety of causes, is a consistent and significant contributor to long-term sodium intake.

”— American Journal of Physiology, 2007

Some researchers theorize that this may be a built-in mechanism for survival, as explained here:

“Salt preferences, which vary widely across individuals, are a function of past exposure to both levels of dietary salt and dehydration. […] It is proposed that an adaptive mechanism calibrates salt preferences as a function of the risk of dehydration as indexed by past dehydration events and maternal salt intake.” — Medical Hypotheses, 2003

All in all, the data seem to suggest that exposure to low salt intake, rather than high salt intake early in life—even before birth—may predict greater salt intake later on. This is the opposite of what we all have been told.

SummaryAll in all, the research has not come to a consensus on sodium intake in infancy. There remain huge gaps in our understanding of “optimal” sodium intake for babies. The proposed “harms” of sodium on infants has not been unequivocally shown in the research to date—not even close.

I would never suggest that an infant should be given lots and lots of salt, but my reason for researching this post was to understand if it’s risky to expose infants to modest levels of sodium from foods eaten by the family.

In other words, do you have to completely overhaul your cooking to omit salt or prepare separate unsalted foods for baby?

If your family eats a lot of processed food, I would definitely pay attention to sodium levels on those products. In the United States, 75% of sodium consumed is from processed foods while only 10% comes from salt added during cooking or at the table.

If your family mostly cooks from scratch, I would not be concerned about seasoning food to taste with salt and offering those same table foods to baby. In reality, this is how most families who practice baby led weaning proceed. There is no preparation of separate foods just for the infant and I’d argue from an ancestral perspective, babies have likely always consumed what the family is eating.

Research shows that adding even a small amount of salt to bitter foods (like vegetables), dramatically improves their palatability, reduces bitterness, and ultimately leads to greater intake by people of all ages, children included.

Much of the picky eating patterns I observe with children, particularly in the rejection of vegetables, seems to be related to their flavor.

As an adult, I can make a choice to force down some tasteless steamed broccoli or bitter kale, but I’ll eat a much larger portion if it’s prepared with some salt (and fat!). Same holds true for children.

(This, by the way, is one of the reasons I wrote my free ebook years ago, “Veggies: Eat Them Because You Want To, Not Because You Have To,” which is available as a free download here.)

In Summary, Here’s What We Know About Salt and Babies:- Breast milk sodium levels are NOT fixed; they vary widely

- The science behind the recommended intakes for sodium for infants is far less evidence based than you’d think; it’s a giant “guesstimate”

- The risk of low blood sodium levels in infants is much more common than high blood sodium levels; high blood sodium levels are most commonly from dehydration, not excessive consumption

- After approximately 4 months of age, infants can more easily excrete sodium in their urine; by 1 year of age, their kidneys can excrete sodium as well as an adult

- Studies have not consistently found salt intake in infancy to be linked to hypertension or salt preference later in life; in fact, exposure to low sodium levels in utero and in infancy predicts greater salt intake later in life

And now, to the question everyone is asking me…

So Lily, do you offer table foods to your baby even if they have salt?If you couldn’t guess, the answer is yes. If you’ve watched my Instagram stories of the foods I’m offering to my baby, you’ll notice they are often the same foods the rest of us are having at that meal.

If you’ve watched my Instagram stories of the foods I’m offering to my baby, you’ll notice they are often the same foods the rest of us are having at that meal.

I do not intentionally add lots of salt to the foods that I’ll be sharing with baby, but they absolutely do contain the usual amount of salt that we cook with for the whole family.

Some would argue that I should just leave salt out of my cooking entirely and add it at the table. But if you’re a foodie, like me, you know that building flavor into meals/entrees involves the addition of salt during the cooking process. This is why you see every single chef on cooking shows add salt while cooking, not at the end.

Adding salt at the table just results in your bland food now tasting salty, not flavorful. If you don’t cook this way yet, you’ll be shocked at how much better everything tastes if you use a little salt while cooking. Moreover, many people add excessive amounts of salt or salty condiments at the table when the food is bland. Or worse, don’t eat much dinner and make up for it with processed snacks in front of the TV.

Or worse, don’t eat much dinner and make up for it with processed snacks in front of the TV.

We don’t even keep a salt shaker at the table because the food I cook is already flavorful. And no, I’m not adding TONS of salt to achieve this.

Keep in mind, however, that we do not consume a lot of processed foods. If this were the case, I’d be more wary about salt for those foods specifically. Processed foods often contain exceedingly high levels of sodium. But the issue isn’t just the salt, it’s the overall lack of nutrition that these foods provide.

Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control show that 58% of sodium consumed by children is from processed foods. As mentioned earlier, the estimates for adults is that 75% of sodium consumed is from processed foods.

Dietary survey studies in the Netherlands find similar patterns; the majority of sodium consumed by children is from bread and cereal products, which suggests this issue is not just limited to the U. S. Only 1% of the sodium in Dutch children’s diet is estimated to come from vegetables.

S. Only 1% of the sodium in Dutch children’s diet is estimated to come from vegetables.

Kids are not consuming excessive sodium because their parents added a sprinkle of salt to the broccoli; they’re consuming it from processed food. If parents fail to make unprocessed food taste good (by making them un-flavorful from intentionally leaving out salt), how can we expect kids to eat more of these foods?

This might just be another unpopular opinion of mine, but I want my children to grow up expecting real food to taste good. For us, that includes cooking with salt, but #youdoyou. I don’t think there’s strong evidence on either side of the “to salt or not to salt” baby food equation here.

Until next time,

Lily

P.S. — Before you go, I’d love to hear from you.

- Do you avoid adding salt to your baby’s foods?

- Were you warned that salt is harmful to infants?

- Were you familiar with the studies presented in this article on salt & babies?

Share your thoughts in the comment section below.

- Institute of Medicine. 2007. Dietary Reference Intakes Research Synthesis: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11767.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for sodium and potassium. National Academies Press, 2019.

- Richards, Anna A., et al. “Breast milk sodium content in rural Gambian women: between‐and within‐women variation in the first 6 months after delivery.” Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 24.3 (2010): 255-261.

- Allen, Jonathan C., et al. “Studies in human lactation: milk composition and daily secretion rates of macronutrients in the first year of lactation.” The American journal of clinical nutrition 54.1 (1991): 69-80.

- Javad, Masoumeh Taravati, et al. “Analysis of aluminum, minerals and trace elements in the milk samples from lactating mothers in Hamadan, Iran.” Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 50 (2018): 8-15.

- Yamawaki, Namiko, et al. “Macronutrient, mineral and trace element composition of breast milk from Japanese women.” Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 19.2-3 (2005): 171-181.

- Dean, R. F. A., and R. A. McCance. “The renal responses of infants and adults to the administration of hypertonic solutions of sodium chloride and urea.” The Journal of physiology 109.1-2 (1949): 81.

- Arant, Billy S. “Postnatal development of renal function during the first year of life.” Pediatric Nephrology 1.3 (1987): 308-313.

- Brion, M. J., et al. “Sodium intake in infancy and blood pressure at 7 years: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children.” European journal of clinical nutrition 62.10 (2008): 1162-1169.

- Rodriguez-Soriano, Juan, et al. “Renal handling of water and sodium in infancy and childhood: a study using clearance methods during hypotonic saline diuresis.” Kidney international 20.6 (1981): 700-704.

- Oddie, S., S. Richmond, and M. Coulthard. “Hypernatraemic dehydration and breast feeding: a population study.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 85.4 (2001): 318-320.

- Dahl, Lewis K., Martha Heine, and Lorraine Tassinari. “High salt content of western infant’s diet: possible relationship to hypertension in the adult.” Nature 198.4886 (1963): 1204-1205.

- Barness, Lewis A, et al. “Committee on Nutrition: Sodium intake of infants in the United States.” Pediatrics 68.3 (1981): 444-445.

- Hofman, Albert, Alice Hazebroek, and Hans A. Valkenburg. “A randomized trial of sodium intake and blood pressure in newborn infants.” Jama 250.3 (1983): 370-373.

- Whitten, Charles F., and Robert A. Stewart. “The effect of dietary sodium in infancy on blood pressure and related factors: studies of infants fed salted and unsalted diets for five months at eight months and eight years of age.” Acta Pædiatrica 69 (1980): 3-17.

- Fleischer Michaelsen K, Weaver L, Branca F, Robertson A (2003).

Feeding and Nutrition of Infants and Young Children. Guidelinesfor the WHO European Region with Emphasis on the Former SovietCountries. WHO Regional Publications, WHO, European Series,No. 87.

Feeding and Nutrition of Infants and Young Children. Guidelinesfor the WHO European Region with Emphasis on the Former SovietCountries. WHO Regional Publications, WHO, European Series,No. 87. - PUYAU, FRANCIS A., and LOIS P. HAMPTON. “Infant feeding practices, 1966: Salt content of the modern diet.” American Journal of Diseases of Children 111.4 (1966): 370-373.

- Stein, Leslie J., Beverly J. Cowart, and Gary K. Beauchamp. “The development of salty taste acceptance is related to dietary experience in human infants: a prospective study.” The American journal of clinical nutrition 95.1 (2012): 123-129.

- Crystal, Susan R., and Ilene L. Bernstein. “Infant salt preference and mother’s morning sickness.” Appetite 30.3 (1998): 297-307.

- Leshem, Micah. “Salt preference in adolescence is predicted by common prenatal and infantile mineralofluid loss.” Physiology & behavior 63.4 (1998): 699-704.

- Stein, L. J., B. J. Cowart, and G.

K. Beauchamp. “Salty taste acceptance by infants and young children is related to birth weight: longitudinal analysis of infants within the normal birth weight range.” European journal of clinical nutrition 60.2 (2006): 272-279.

K. Beauchamp. “Salty taste acceptance by infants and young children is related to birth weight: longitudinal analysis of infants within the normal birth weight range.” European journal of clinical nutrition 60.2 (2006): 272-279. - Shirazki, Adi, et al. “Lowest neonatal serum sodium predicts sodium intake in low birth weight children.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 292.4 (2007): R1683-R1689.

- Fessler, D. M. T. “An evolutionary explanation of the plasticity of salt preferences: prophylaxis against sudden dehydration.” Medical hypotheses 61.3 (2003): 412-415.

- Ha SK. Dietary salt intake and hypertension. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2014;12(1):7–18. doi:10.5049/EBP.2014.12.1.7

- Bakke, Alyssa J., et al. “Mary Poppins was right: Adding small amounts of sugar or salt reduces the bitterness of vegetables.” Appetite 126 (2018): 90-101.

- Bouhlal, Sofia, et al. “‘Just a pinch of salt’.

An experimental comparison of the effect of repeated exposure and flavor-flavor learning with salt or spice on vegetable acceptance in toddlers.” Appetite 83 (2014): 209-217.

An experimental comparison of the effect of repeated exposure and flavor-flavor learning with salt or spice on vegetable acceptance in toddlers.” Appetite 83 (2014): 209-217. - Quader, Zerleen S., et al. “Sodium intake among US school-aged children: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 117.1 (2017): 39-47.

- Goldbohm, R. Alexandra, et al. “Food consumption and nutrient intake by children aged 10 to 48 months attending day care in the Netherlands.” Nutrients 8.7 (2016): 428.

Is it necessary to salt baby food

Reviewer Kovtun Tatiana Anatolievna

10642 views

September 15, 2021

The salt we use every day in cooking is called sodium chloride. But if we talk about salt from the point of view of the human diet, then it makes sense to consider two elements, chlorine and sodium

But if we talk about salt from the point of view of the human diet, then it makes sense to consider two elements, chlorine and sodium

Sodium and chlorine ions play an enormous role in the human body - they maintain homeostasis (the constancy of the internal environment of the body), the level of fluid concentration inside and outside the cells necessary for normal life, ensure the normal permeability of the membrane of each cell in the body, participate in the conduction of electrical impulses in cells and perform a number of other physiological functions.

But do not immediately reach for the salt shaker.

Firstly, salt in its natural form can be obtained from many products, and secondly, there are strict restrictions on salt intake, and if they are not observed, then you can harm the body.

After all, a number of important mechanisms (renal, adrenal, vascular, etc.) are responsible for maintaining the balance of sodium and chlorine ions in the body, which, with excessive intake of salt from food, can experience excessive stress, and some systems can even fail.

Today we will talk about the “salt” subtleties.

To salt or not to salt - that is the question

As for children, experts are unanimous in their opinion: infants do not need salt "from the outside" at all. Nature made sure that there was enough of it in mother's milk. By the way, it is equally important that mommy does not lean heavily on salty food.

And if the baby is bottle-fed, then the principle is the same - the balance of all the necessary elements has already been observed in the mixtures.

Salt can only be administered after breastfeeding or artificial feeding is completed, usually this happens at 1 or 1.5 years old. The baby will receive a third of the daily intake of sodium and chlorine "naturally" - from vegetables, fruits, cereals, meat and fish.

- Here are some foods from the high sodium diet for children:

- egg

- sardine

- cottage cheese

- kefir

- tomatoes

- oats

- apples

- carrots

- And foods that are rich in chlorine :

- beef

- rice

- buckwheat

- egg white

But the remaining two-thirds of the norm for the baby can be obtained with the help of table salt. The rules of "pinch" or "tip of a knife" do not work very well here - these are not perfect measures of measurement. The only thing that parents should be guided by is that children's food should a priori seem unsalted and fresh for an "adult" taste.

The rules of "pinch" or "tip of a knife" do not work very well here - these are not perfect measures of measurement. The only thing that parents should be guided by is that children's food should a priori seem unsalted and fresh for an "adult" taste.

Additional salting of industrial products for children 1–3 years old is prohibited. Children's "salt norm" per day is about 0.5 g per 10 kg of body weight.

What happens if you add too much salt to baby food

The urinary system of the baby will hardly get rid of the excess of this mineral. The load on fragile kidneys, pancreas, blood vessels will increase, and disturbances in water-salt metabolism are also possible.

Alarming signals for parents can be the presence of edema in the child, unreasonable anxiety of the crumbs and a decrease in the number of urination.

Which salt to choose for the baby

In baby food, it is recommended to use regular table salt. Black, Himalayan pink or sea salt is not suitable for crumbs. Separately, it should be said about iodized salt - it can be included in the diet only after consulting with a pediatrician.

Separately, it should be said about iodized salt - it can be included in the diet only after consulting with a pediatrician.

It is better to add salt to dishes after they are cooked, so that useful substances do not evaporate after heat treatment.

The task of parents is to form the right attitude towards salt in the baby, without “hammering” the natural taste of products with it, but also without making it a taboo.

Find your balance and grow healthy!

Reviewer Kovtun Tatiana Anatolievna

Scientific adviser to PROGRESS JSC, Candidate of Medical Sciences

All expert articles

Is it necessary to salt the food of a child up to a year

— Anastasia Ivanovna, what role does salt play in metabolic processes and why is it harmful?

- These questions are often asked during consultations. You can't do without salt. The basis of table salt is sodium chloride, which:

You can't do without salt. The basis of table salt is sodium chloride, which:

- helps to improve metabolism;

- has a beneficial effect on the pH balance;

- stabilizes hydrobalance;

- affects blood metabolism;

- prevents dehydration.

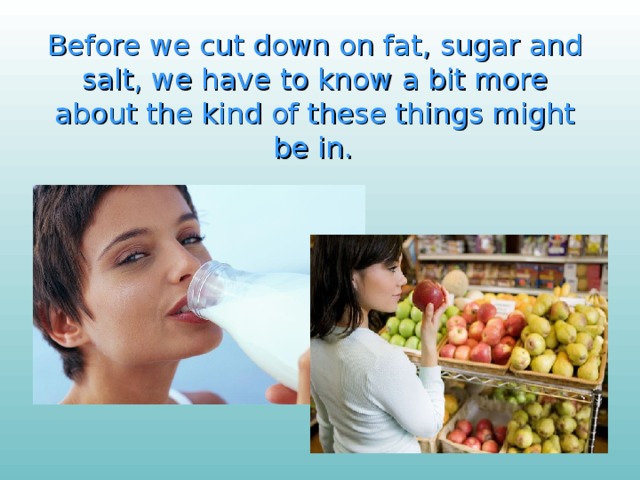

The value of salt for the body is high, but we forget that vegetables, fruits, bread and other products already contain salt. And we don’t think about it, so an excess of salt often occurs in the body.

Pay attention! When sodium chloride is low, there may be loss of appetite, abdominal pain, nausea, and excessive flatulence. Someone also talks about dizziness and a drop in blood pressure, but all conditions should be observed with doctors.

Why don't they salt their food to children? And in general - do children need to salt their food?

- As I said, many foods contain natural salt. It is so thought out by nature that children receive the first salt from breast milk or formula and in a form that does not harm them. For example, 100 ml of breast milk contains 0.17 sodium. From six months, you can switch to other types of food, making sure that it is suitable for your child's age. I will especially note that cow's milk contains more salt than goat's milk, but in any case, whole milk is not recommended for babies under a year and a half years old.

For example, 100 ml of breast milk contains 0.17 sodium. From six months, you can switch to other types of food, making sure that it is suitable for your child's age. I will especially note that cow's milk contains more salt than goat's milk, but in any case, whole milk is not recommended for babies under a year and a half years old.

- And yet, from the point of view of pediatricians, when is it possible to salt food for a child?

— Pediatricians recommend starting salting complementary foods no earlier than 7-8 months, but I would advise you to refrain from salt in the diet of a child up to a year. At the age of the start of complementary foods, the kidneys have not yet formed: they are not able to filter a lot of salt. You can provoke overexcitation, kidney and joint diseases.

— What are the supposed health benefits of salt?

- Babies who sweat a lot are thought to lose sodium chloride. In fact, you need to think about dehydration. And it is better to replenish it not with salty foods, but by supplementing it with clean water separately from feeding. And, of course, you need to find out why the child is losing a lot of fluid.

And, of course, you need to find out why the child is losing a lot of fluid.

For example,

the potassium-sodium balance in the cells is formed provided that there is enough vitamin D in the body. For some reason everyone forgets about this, but it is the level of vitamin D that you need to think about if the child sweats a lot. Hyponatremia (decreased serum sodium concentration) causes severe dehydration in case of diarrhea and vomiting, which means that the child loses a lot of water in a short period of time. In such conditions, it is imperative to consult a doctor, take tests, and the question of salting or not salting food will not solve the problem.

Another example is that salt improves appetite,

this is a known fact. Salt increases the amount of saliva, increases the acidity of gastric juice and at the same time exacerbates the desire to eat. In 2008, an interesting study was conducted at the University of Iowa: rats were first fed salty food, and then deprived of salt, which led to irritation. When the rodents were again added salt to their food, they showed cheerfulness and good mood. This is an indicator that salt increases appetite and changes behavior.

When the rodents were again added salt to their food, they showed cheerfulness and good mood. This is an indicator that salt increases appetite and changes behavior.

If you add a lot of salt to baby food, then the child will get used to this amount and then will protest against insipid food. What to do? Gradually reduce the amount of salt or limit it completely, eliminating all salt reserves, and if age allows, add foods with a salty taste: orange, cranberry, pomegranate juice, onion, garlic, radish, parsley.

— How much salt does a child need?

- Until the year it is better not to add anything - the child will receive sodium chloride with food. In extreme cases, add salt from eight months - no more than 1 g per day. After a year, you can slowly introduce salt, but also in reasonable quantities, without overdoing it.

Types of salt: what can children do

— There is an opinion: in order to make salt more accessible to the child's body, its solution is evaporated in a water bath. But I never met parents who did it at home. When choosing salt, you need to carefully read the compositions, evaluate the condition and reaction of the child to salt, and remember the expiration dates.

But I never met parents who did it at home. When choosing salt, you need to carefully read the compositions, evaluate the condition and reaction of the child to salt, and remember the expiration dates.

— What salty foods are strictly prohibited for children and why?

- Salted straws, fish or nuts, even for an adult organism, have an excess of salt. In them, the allowable dosage of salt is almost 17-20 times exceeded, which loads the liver, kidneys, and blood vessels.

Pediatricians and pediatric gastroenterologists recommend not giving your child sugar and salt until they can do without them. Dentists talk about the age of three or four years and the restriction of sweets. But in big cities, children try everything earlier. And as soon as the child gets acquainted with the taste of salted or sweet food, the process cannot be stopped, he will continue to ask for such food, since his receptors will only respond to it. Therefore, young children should be limited in salt and sugar, including their solutions in water.

When choosing products, it is necessary to focus on the age of the child and do not forget that by adding food, we increase the natural dosage.

— Is it possible to replace salt with something?

- Some mothers replace salt with kelp - they buy it in pharmacies, grind it into dust and add salt to food. But they forget that kelp is an iodine-containing product that is undesirable in the diet of children with hypersensitivity to iodine. In addition, kelp is indicated for chronic constipation, and when eaten, it will take water from the body. So, in order not to get dehydrated, you need to increase your water intake. Increasing in volume, it irritates the mucosal receptors and increases intestinal motility, which means that the child will go to the toilet more often. Therefore, replacing salt with something, you need to evaluate all the pros and cons.

— Is there salt in prepared vegetable and meat purees, cereals and cream soups?

— When choosing food for a child, it is important to read the ingredients.