Can i feed my baby breast milk after drinking

Alcohol | Breastfeeding | CDC

What is “moderate consumption”?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans defines moderate consumption for women of legal drinking age as up to 1 standard drink per day.

What is a “drink”?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans defines a standard “drink” as 12 ounces of 5% beer; 8 ounces of 7% malt liquor; 5 ounces of 12% wine; or 1.5 ounces of 40% (80 proof) liquor. All of these drinks contain the same amount (i.e., 14 grams, or 0.6 ounces) of pure alcohol. However, many common drinks contain much more alcohol than this. For example, 12 ounces of 9% beer contains nearly the same amount of alcohol as two (1.8) standard drinks. Consuming one of these drinks would be the equivalent of two standard drinks.

Is it safe for mothers to breastfeed their infant if they have consumed alcohol?

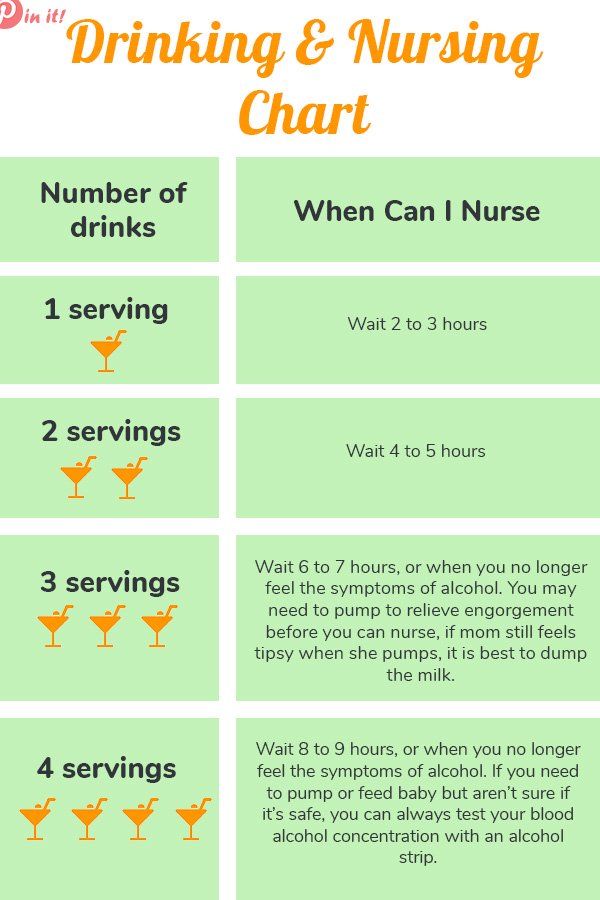

Not drinking alcohol is the safest option for breastfeeding mothers. Generally, moderate alcohol consumption by a breastfeeding mother (up to 1 standard drink per day) is not known to be harmful to the infant, especially if the mother waits at least 2 hours after a single drink before nursing. However, exposure to alcohol above moderate levels through breast milk could be damaging to an infant’s development, growth, and sleep patterns. Alcohol consumption above moderate levels may also impair a mother’s judgment and ability to safely care for her child.

Drinking alcoholic beverages is not an indication to stop breastfeeding; however, consuming more than one drink per day is not recommended.

Can alcohol be found in breast milk?

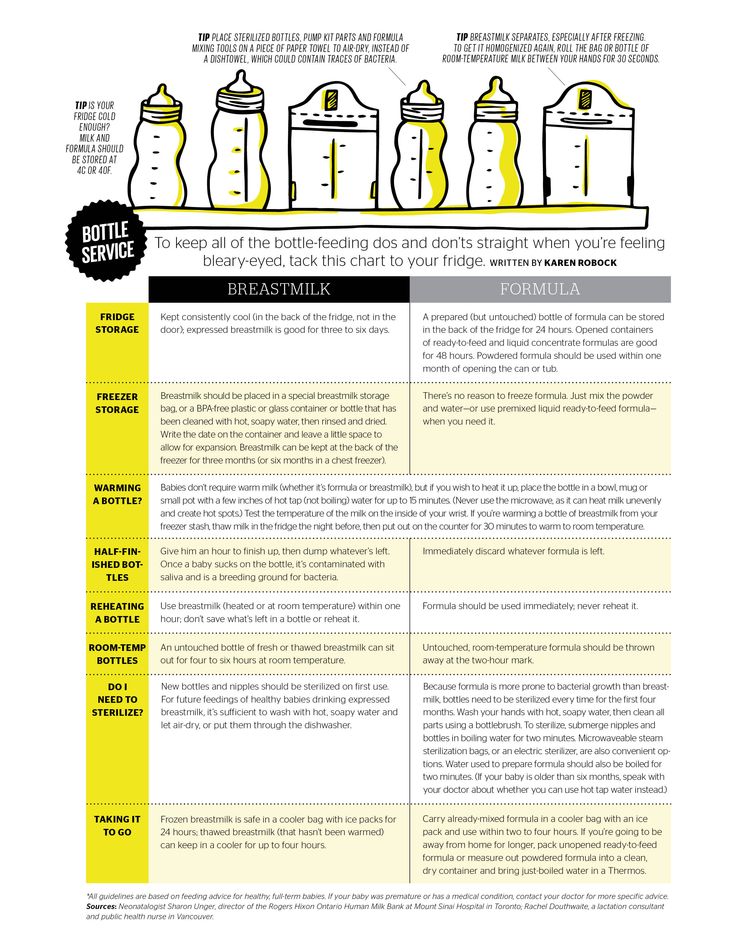

Yes. Alcohol levels are usually highest in breast milk 30-60 minutes after an alcoholic beverage is consumed, and can be generally detected in breast milk for about 2-3 hours per drink after it is consumed. However, the length of time alcohol can be detected in breast milk will increase the more alcohol a mother consumes. For example, alcohol from 1 drink can be detected in breast milk for about 2-3 hours, alcohol from 2 drinks can be detected for about 4-5 hours, and alcohol from 3 drinks can be detected for about 6-8 hours, and so on. However, blood alcohol levels and the length of time alcohol can be detected in breast milk after drinking will depend on a number of factors, including the amount of alcohol consumed, how fast the alcohol is consumed, whether it is consumed with food, how much a mother weighs, and how fast alcohol is broken down in a mother’s body.

However, blood alcohol levels and the length of time alcohol can be detected in breast milk after drinking will depend on a number of factors, including the amount of alcohol consumed, how fast the alcohol is consumed, whether it is consumed with food, how much a mother weighs, and how fast alcohol is broken down in a mother’s body.

What effect does alcohol have on a breastfeeding infant?

Moderate alcohol consumption by a breastfeeding mother (up to 1 standard drink per day) is not known to be harmful to the infant, especially if the mother waits at least 2 hours before nursing. However, higher levels of alcohol consumption can interfere with the milk ejection reflex (letdown) while maternal alcohol levels are high. Over time, excessive alcohol consumption could lead to shortened breastfeeding duration due to decreased milk production. Excessive alcohol consumption while breastfeeding could also affect the infant’s sleep patterns and early development.

Alcohol and Caregivers

Caring for an infant while intoxicated is not safe. Drinking alcohol could impair a caregiver’s judgement and his or her ability to safely care for an infant. If a caregiver drinks excessively, he or she should arrange for a sober adult to care for the infant during this time.

Drinking alcohol could impair a caregiver’s judgement and his or her ability to safely care for an infant. If a caregiver drinks excessively, he or she should arrange for a sober adult to care for the infant during this time.

Can expressing/pumping breast milk after consuming alcohol reduce the alcohol in the mother’s milk?

No. The alcohol level in breast milk is essentially the same as the alcohol level in a mother’s bloodstream. Expressing or pumping milk after drinking alcohol, and then discarding it (“pumping and dumping”), does NOT reduce the amount of alcohol present in the mother’s milk more quickly. As the mother’s alcohol blood level falls over time, the level of alcohol in her breast milk will also decrease. A mother may choose to express or pump milk after consuming alcohol to ease her physical discomfort or adhere to her milk expression schedule. If a mother decides to express or pump milk within two hours (per drink) of consuming alcohol, the mother may choose to discard the expressed milk. If a mother has consumed more than a moderate amount of alcohol, she may choose to wait 2 hours (per drink) to breastfeed her child, or feed her infant with milk that had been previously expressed when she had not been drinking, to reduce her infant’s exposure to alcohol. Breast milk continues to contain alcohol as long as alcohol is still in the mother’s bloodstream.

If a mother has consumed more than a moderate amount of alcohol, she may choose to wait 2 hours (per drink) to breastfeed her child, or feed her infant with milk that had been previously expressed when she had not been drinking, to reduce her infant’s exposure to alcohol. Breast milk continues to contain alcohol as long as alcohol is still in the mother’s bloodstream.

Alcohol and breastfeeding: What are the risks?

Although the harmful effects of alcohol use during pregnancy are well documented and recommendations to avoid alcohol during pregnancy are clear, the risks of alcohol use during lactation are less understood.

When patients ask medical professionals for guidance about the safety of consuming alcoholic beverages during lactation, they often are met with conflicting advice. Providers and patients are tasked with navigating the limited information available on this very relevant topic.

Because of the lack of definitive data around lactation and alcohol consumption, recommendations from professional organizations vary (Table 1).

The World Health Organization recommends avoiding alcohol during lactation,1 whereas the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that occasional alcohol use equivalent to 8 oz of wine or 2 cans of beer per day may be acceptable and that waiting 2 hours after the last drink before breastfeeding is sufficient.2,3 The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine offers similar advice, also acknowledging that the long-term effects of alcohol in human milk remain unknown.4 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has guidance directed toward parents in which it recommends waiting at least 2 hours after a single drink before breastfeeding; however, an ACOG Committee Opinion recommends that “a mother should be encouraged by her health care provider to wait 3 to 4 hours after a single drink before breastfeeding her infant.”5,6

Alcohol is ubiquitous in our society, and many females wish to resume alcohol use during lactation after abstaining during pregnancy. In 2019, more than half of the US adult population drank alcohol in the past 30 days. About 26% of the adult population reported binge drinking (for women, 4 or more drinks on 1 occasion) and 6.3% reported heavy drinking (for women, 8 or more drinks per week) in the past month.7

In 2019, more than half of the US adult population drank alcohol in the past 30 days. About 26% of the adult population reported binge drinking (for women, 4 or more drinks on 1 occasion) and 6.3% reported heavy drinking (for women, 8 or more drinks per week) in the past month.7

Although about 50% of lactating females reported using alcohol at least occasionally, only 13% reported being counseled by their health care provider about the risks of alcohol use during lactation.8,9

Because of the high prevalence of alcohol consumption and the fact that 58% of infants in the US are breastfeeding for at least 6 months, health care providers will encounter questions from patients about the safety of alcohol use during lactation.10 Any advice to restrict lactation because of maternal alcohol intake must be balanced carefully with the known maternal and infant health benefits of lactation. Although data are limited on this topic, much is known and should be communicated to patients during pregnancy and postpartum care.

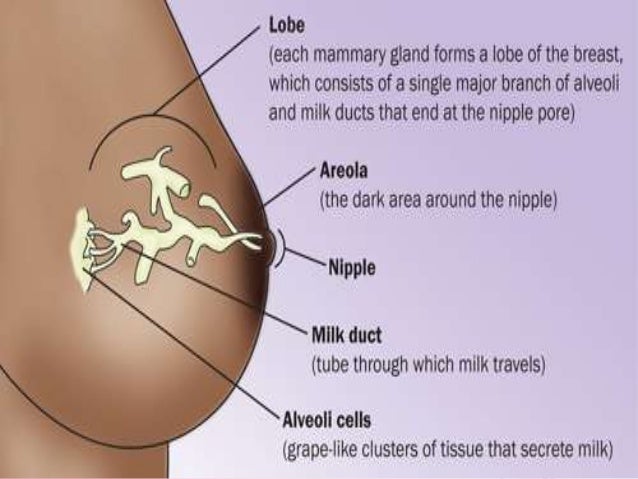

Alcohol is a small (46 Da) and very water-soluble molecule, so it passes freely into human milk.11 Therefore, levels of alcohol in milk closely parallel maternal blood alcohol concentrations. The milk alcohol levels peak about 30 to 60 minutes after consumption of an alcoholic beverage, but the peak can be delayed by an additional hour if alcohol is consumed with food.

The overall bioavailability of alcohol in lactating females is about 25% lower when compared with nonlactating females, resulting in lower peak alcohol blood levels, but the time to the peak blood alcohol levels is the same.11 Feeding or expressing milk prior to alcohol consumption may contribute further to decreased bioavailability.12 If an infant consumes milk during the time of maximum alcohol concentration, the amount of alcohol the infant consumes is estimated to be about 5% to 6% of the weight-adjusted maternal intake. 9

9

Alcohol elimination from breast milk depends largely upon maternal weight and the amount of alcohol consumed. The more alcohol is consumed, the longer it will be present in the milk.

After drinking a standard single drink (Figure 1), alcohol is typically detected in milk for approximately 2.5 hours for a 132.3-lb person (60 kg). If a second beverage is consumed, the time to eliminate alcohol doubles and alcohol will be detectable in milk for closer to 5 hours. If a binge-drinking episode occurs, alcohol may be detected for more than 9 hours.11

Although alcohol test strips have been used to determine the presence of alcohol in milk, it is more reliable to use nomograms to determine when milk is free of alcohol (Table 2).

Once alcohol-containing milk is consumed, it is absorbed by the infant. Calculations estimate that infant blood alcohol levels would reach about 0.005% after consuming human milk following maternal consumption of 4 standard drinks. 9 The rate at which an infant can metabolize alcohol is about half that of adults because of immature metabolic pathways that detoxify alcohol.13

9 The rate at which an infant can metabolize alcohol is about half that of adults because of immature metabolic pathways that detoxify alcohol.13

Little and colleagues hypothesized that the infant brain may be exquisitely sensitive to alcohol even in these small quantities because of the infant’s rapid brain growth and immature metabolism.14

Is “pump and dump” a way to eliminate alcohol?It is not necessary to pump and dump milk after consuming alcohol. This will not speed the elimination of alcohol from milk. However, if alcohol use results in delayed or skipped feeding, expressing milk can maintain supply and avoid complications of engorgement.15

Is alcohol a galactagogue?Contrary to folklore advocating the use of alcohol to stimulate milk production, alcohol has been shown to decrease milk production, at least temporarily.16 It interacts with the neuroendocrine axis, disrupting the hormones that influence lactation. Alcohol inhibits the release of oxytocin, the hormone responsible for the milk ejection reflex.

Alcohol inhibits the release of oxytocin, the hormone responsible for the milk ejection reflex.

Alcohol in doses of 0.5 g/kg (which is about 8 oz of wine or 2 beers for a 132.3-lb individual [60 kg]) has been shown to reduce oxytocin response to suckling by 18%; doses of 1.5 g/kg have been shown to reduce oxytocin response by 80%. Consequently, lactating females who consume alcohol may experience delays in milk letdown ranging from about 30 seconds for lower doses and as high as 330 seconds with higher doses of alcohol exposure.17

In contrast, prolactin levels increase in response to alcohol consumption. Although prolactin is a hormone important for milk production, the observed increases in prolactin levels after alcohol intake have not been associated with increased milk production.18

Beer has a reputation for increasing milk supply. The polysaccharide found in barley and malt has been shown to increase serum prolactin levels in nonpregnant, nonlactating females. However, infants consumed 23% less milk in the hours following maternal alcoholic beer consumption (versus nonalcoholic beer), and beer is not recommended for use as a galactagogue.19

However, infants consumed 23% less milk in the hours following maternal alcoholic beer consumption (versus nonalcoholic beer), and beer is not recommended for use as a galactagogue.19

Overall, infants consume about 20% less milk during the immediate hours after maternal alcohol consumption, likely because of diminished milk production. The decrease in milk intake by the infant is not related to a decreased time spent suckling, or to an infant rejecting the flavor of the milk.

In fact, Mennella observed that infants consumed larger amounts of milk flavored with alcohol compared with unaltered milk when offered both options through the bottle.20 Infants appear to compensate for decreased feeding volumes by breastfeeding more frequently in the 8 to 16 hours after maternal alcohol consumption.21

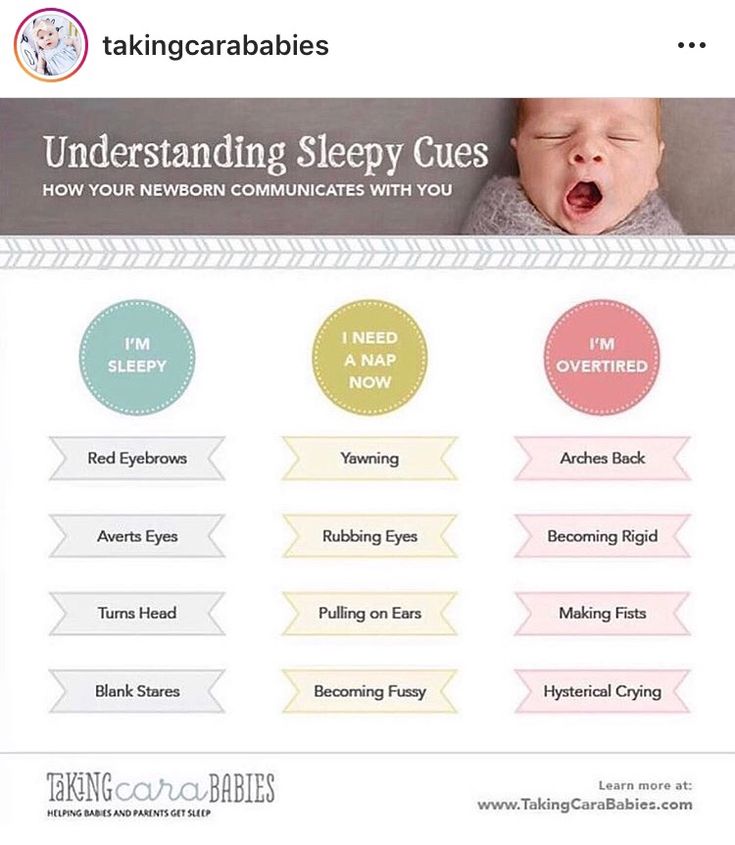

Alcohol use, infant sleepEven small amounts of alcohol in human milk have been shown to disrupt and shorten total duration of infant sleep. Mennella and Garcia-Gomez observed infants after consumption of milk 1 hour after maternal intake of 0.3 g/kg of alcohol (slightly more than 1 standard drink for a 132.3-lb. person [60 kg]), and sleep was noted to be more fragmented and was overall diminished during the 3.5 to 4 hours that followed.

Mennella and Garcia-Gomez observed infants after consumption of milk 1 hour after maternal intake of 0.3 g/kg of alcohol (slightly more than 1 standard drink for a 132.3-lb. person [60 kg]), and sleep was noted to be more fragmented and was overall diminished during the 3.5 to 4 hours that followed.

When infants were observed for 24 hours, they appeared to compensate by spending more time in active sleep from 3.5 to 24 hours following consumption of alcohol-containing milk.22 Infants exposed to even low doses of alcohol in milk may experience more arousal than sedation.

Schuetz and colleagues observed infants to be fussier, with more frequent crying and startling, in the hour following the consumption of alcohol-containing milk. Although some of this behavior may have been explained by maternal behavior after alcohol consumption, these findings are consistent with the diminished sleep and increased infant arousal noted in other studies.23

Long-term impactsThe long-term impacts of an infant’s exposure to alcohol through human milk are not definitively understood. It is a challenging topic to study because the impact of dyad interactions after maternal alcohol consumption may play a role in neurodevelopmental outcomes.

It is a challenging topic to study because the impact of dyad interactions after maternal alcohol consumption may play a role in neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Also, it is difficult to quantify the amount of alcohol to which an infant is exposed, and information about quantity of maternal alcohol intake and timing of subsequent feeds is not usually available. In contrast, there is clear evidence that fetal exposure to alcohol during pregnancy can have adverse physical and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.24 Little and colleagues evaluated infants who were exposed to alcohol through human milk for both cognitive and psychomotor development.

Although cognitive outcomes at 1 year were not shown to be affected by maternal alcohol use, a measurable decrease in motor function development was noted. However, when the infants were evaluated as 18-month-olds, this deficit was no longer demonstrated.14,25 Data regarding alcohol consumption during lactation and academic outcomes are limited.

May and colleagues analyzed outcomes of first-grade students who had been exposed to alcohol during lactation, and they were noted to have poorer grammatical comprehension than nonexposed children.26

Gibson and Porter found no relationship between lactational alcohol exposure and either vocabulary or early literacy scores. They did, however, observe a dose-dependent reduction in abstract reasoning and cognitive abilities at age 6 to 7 years.27 Subsequent analysis of these outcomes revealed that increased or riskier maternal alcohol consumption during lactation was associated with dose-dependent reductions in grade 3 (aged 7-10 years) writing, spelling, grammar, and punctuation scores, as well as grade 5 (aged 9-11 years) spelling scores.28 These findings suggest that alcohol exposure during lactation may later affect a child’s academic performance.

Clinical guidanceLactating females should be instructed to minimize their infants’ exposure to alcohol when they choose to consume alcoholic beverages. An individual can be advised to feed or express milk just prior to alcohol consumption.

An individual can be advised to feed or express milk just prior to alcohol consumption.

The number of alcoholic beverages should ideally be limited to 1 drink per day or less during lactation, and binge drinking should be avoided.15 Lactating females should be advised that the AAP guidance regarding safe infant sleep recommends avoiding alcohol use because of infant safety concerns.29 Parental alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome. This risk is particularly high when a parent who has consumed alcohol shares a bed with an infant.30

Breastfeeding while under the influence of alcohol may exacerbate this risk. Although the absolute dose of alcohol transferred to an infant through milk is quite small and may be considered negligible when compared with relative adult doses, parents should be provided with information about the short-term impacts on an infant exposed to alcohol via human milk.22,23

They also should be informed that limited data reveal a possible link between an infant’s alcohol exposure and later academic performance. 28

28

Lactating females should be routinely screened for past and current use of alcohol using a validated screening tool. Effective screening tools are available online through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The NIDA Quick Screen evaluates alcohol and other substances (Figure 2).30

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test is a screening tool for alcohol use.31,32 The results can guide conversations with patients about alcohol use during lactation. When making recommendations about the duration of time to avoid feeding after alcohol intake, it is important to consider the total number of alcoholic beverages consumed.

A conservative approach would recommend accurate monitoring of alcohol consumption along with the use of a nomogram to calculate the time needed to completely clear alcohol from milk after maternal consumption of an alcoholic beverage before resuming lactation (Table 2).

Alternatively, a lactating female should wait at least 2 to 3 hours before directly feeding her baby milk after a single drink. 5 If the baby becomes hungry before that time, previously expressed milk may be offered to the baby. Although there is no known safe amount of alcohol exposure to an infant, occasional moderate (1 drink or less) maternal alcohol use during lactation has not demonstrated harmful effects on infants and therefore should not prompt weaning.

5 If the baby becomes hungry before that time, previously expressed milk may be offered to the baby. Although there is no known safe amount of alcohol exposure to an infant, occasional moderate (1 drink or less) maternal alcohol use during lactation has not demonstrated harmful effects on infants and therefore should not prompt weaning.

Further research on the long-term developmental impacts of alcohol exposure on infants through human milk will help to inform patients and providers in the future.

References

1. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy. World Health Organization. November 19, 2014. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548731

2. Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552

3. Sachs HC; Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

doi:10.1542/peds.2013-1985

4. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(3):135-141. doi:10.1089/bfm.2015.9992

5.Breastfeeding your baby. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Breastfeeding Your Baby. Updated May 2021. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/breastfeeding-your-baby

6. Committee opinion no. 496: at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence: obstetric and gynecologic implications. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):383-388. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c9906

7. Alcohol facts and statistics. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Updated June 2021. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics

8. Haastrup MB, Pottegård A, Damkier P. Alcohol and breastfeeding. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;114(2):168-173. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12149

9. Pepino MY, Mennella JA. Advice given to women in Argentina about breast-feeding and the use of alcohol. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2004;16(6):408-414.

doi:10.1590/s1020-49892004001200007

10. Breastfeeding report card—United States, 2020. CDC. Updated September 17, 2020. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm

11. Anderson PO. Alcohol use during breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(5):315-317.doi:10.1089/bfm.2018.0053

12. Mennella JA, Pepino MY. Breast pumping and lactational state exert differential effects on ethanol pharmacokinetics. Alcohol. 2010;44(2):141-148. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.011

13. Horst PG, Madjunkov M, Chaudry S. Alcohol: a pharmaceutical and pharmacological point of view during lactation. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2016;23(2):e145-e150.

14.Little RE, Anderson KW, Ervin CH, Worthington-Roberts B, Clarren SK. Maternal alcohol use during breast-feeding and infant mental and motor development at one year. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(7):425-430. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908173210703

Maternal alcohol use during breast-feeding and infant mental and motor development at one year. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(7):425-430. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908173210703

15. Alcohol. CDC. Updated February 9, 2021. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/vaccinations-medications-drugs/alcohol.html

16. Mennella JA. Short-term effects of maternal alcohol consumption on lactational performance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(7):1389-1392.

doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03924.x

17. Cobo E. Effect of different doses of ethanol on the milk-ejecting reflex in lactating women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;115(6):817-821. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(73)90526-7

18.Mennella JA, Pepino MY, Teff KL. Acute alcohol consumption disrupts the hormonal milieu of lactating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):1979-1985. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1593

19. Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. Beer, breast feeding, and folklore. Dev Psychobiol. 1993;26(8):459-466. doi:10.1002/dev.420260804

Dev Psychobiol. 1993;26(8):459-466. doi:10.1002/dev.420260804

20. Mennella JA. Infants’suckling responses to the flavor of alcohol in mothers’ milk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21(4):581-585.

21. Mennella JA. Regulation of milk intake after exposure to alcohol in mothers’ milk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(4):590-593.

22. Mennella JA, Garcia-Gomez PL. Sleep disturbances after acute exposure to alcohol in mothers’ milk. Alcohol. 2001;25(3):153-158. doi:10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00175-6

23. Schuetze P, Eiden RD, Chan AWK. The effects of alcohol in breast milk on infant behavioral state and mother-infant feeding interactions. Infancy. 2002;3(3):349-363.

doi:10.1207/S15327078IN0303_4

24. Dejong K, Olyaei A, Lo JO. Alcohol use in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62(1):142-155. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000414

25. Little RE, Northstone K, Golding J; ALSPAC Study Team. Alcohol, breastfeeding, and development at 18 months. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):E72-E72. doi:10.1542/peds.109.5.e72.

Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):E72-E72. doi:10.1542/peds.109.5.e72.

26. May PA, Hasken JM, Blankenship J, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal alcohol use: prevalence and effects on child outcomes and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;63:13-21. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.05.002

27. Gibson L, Porter M. Drinking or smoking while breastfeeding and later cognition in children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20174266. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4266

28. Gibson L, Porter M. Drinking or smoking while breastfeeding and later academic outcomes in children. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):829. doi:10.3390/nu12030829

29. Moon RY; Task Force On Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2940

30. The NIDA quick screen. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide-screening-drug-use-in-general-medical-settings/nida-quick-screen

https://archives.drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide-screening-drug-use-in-general-medical-settings/nida-quick-screen

31. Instrument: AUDIT-C questionnaire. NIDA CTN Common Data Elements. Accessed June 11, 2021. https://cde.drugabuse.gov/instrument/f229c68a-67ce-9a58-e040-bb89ad432be4

32. Wright TE, Terplan M, Ondersma SJ, et al. The role of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the perinatal period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):539-547. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.038

Feeding when sick | Medela

If you or your baby are unwell, you may wonder if it is safe to breastfeed. The great news is that breastfeeding when you're sick is most often good for both of you. Read more about this in our article.

Share this information

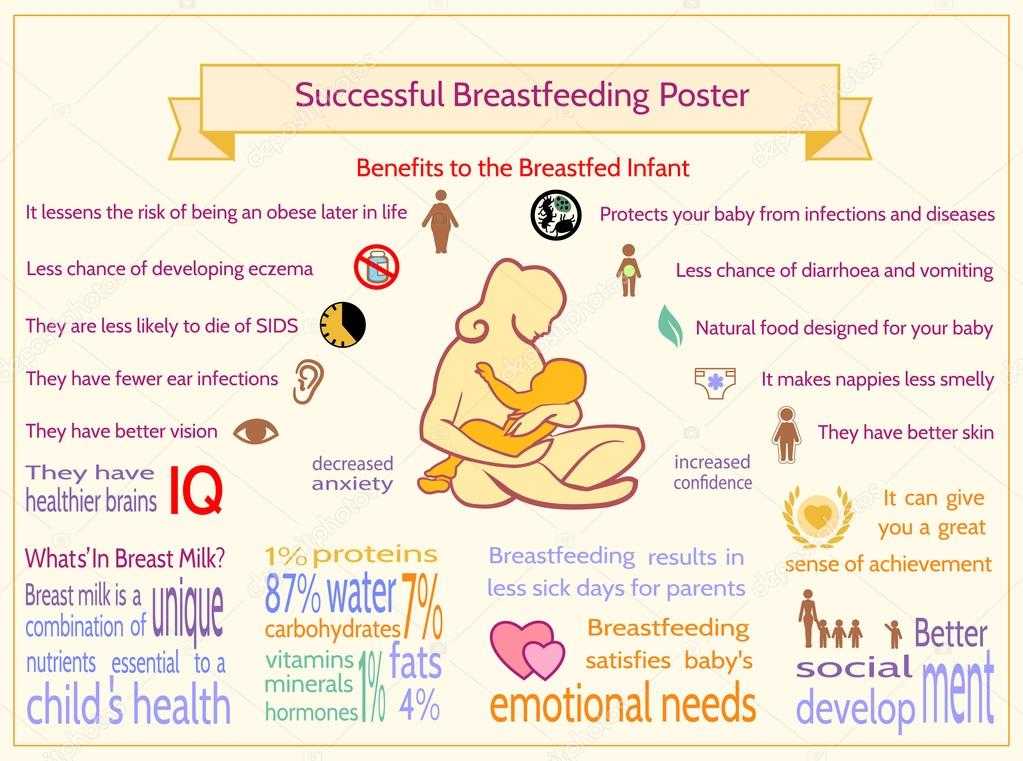

Did you know that a breastfed baby is usually much less prone to illness? Although it is impossible to avoid them completely, the protective properties of breast milk help babies get sick less often 1 and recover faster than formula-fed babies.

Breast milk contains antibacterial and antiviral agents. 2 The longer you breastfeed your baby, the lower the risk of colds and flu, ear and respiratory infections, nausea and diarrhea. 1 Scientists are already exploring the use of breast milk to treat everything from conjunctivitis to cancer. 3.4

Should a sick baby be breastfed?

Yes. Breastfeeding promotes recovery and also helps to calm the baby. Breast milk contains antibodies, white blood cells, stem cells, and protective enzymes that help fight infections and help your baby recover faster. 1,5,6 In addition, the composition of breast milk (the balance of vitamins and nutrients) is constantly adjusted to the baby's body to help him recover as soon as possible. Thus, you will spend less time on sick leave and visit the doctor less often. 7

“Breastfeeding gives the baby everything she needs when she is sick. This is his medicine, food, drink and comfort. For a baby, this is the best thing in the world,” says Sarah Beeson, a health visitor from the UK.

For a baby, this is the best thing in the world,” says Sarah Beeson, a health visitor from the UK.

Surprisingly, when a child becomes ill, the composition of breast milk changes. When you come into contact with pathogens of bacterial and viral infections, your body begins to produce antibodies to fight them, which are then passed through milk to your baby. 8 When your baby is sick, your milk also spikes in immune-boosting cells (white blood cells). 5

In addition, breast milk is very easy to digest, making it ideal for babies with indigestion.

“At 12 months my daughter contracted norovirus and could only breastfeed,” recalls Maya, a mother of two in Spain. produce more milk. It was amazing. After 48 hours, I was able to meet the daily requirement for milk. It saved my baby from a drip."

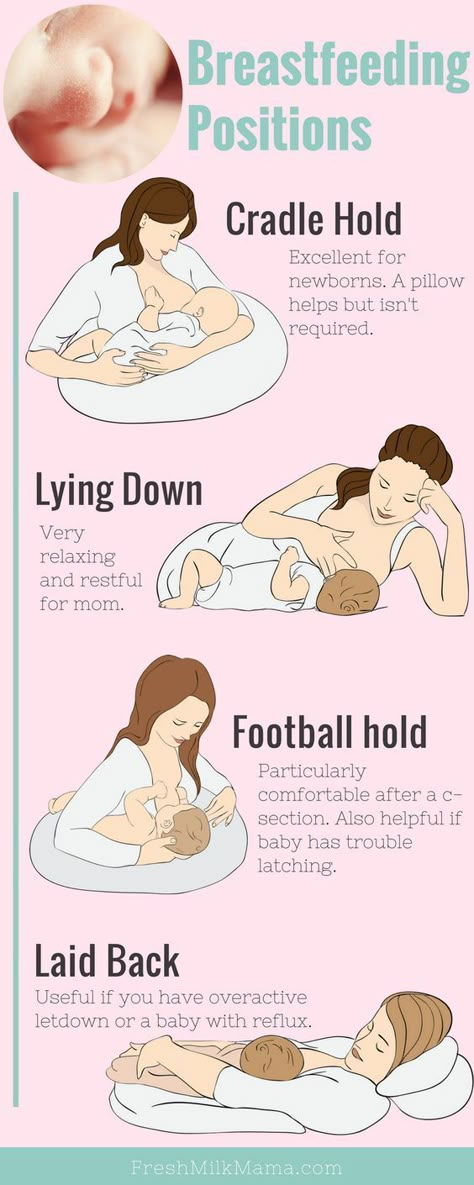

It should be taken into account that sometimes during an illness it is necessary to change the habitual breastfeeding regimen. For example, with a cold, a baby may want to eat more often, but little by little, both to calm down and because of nasal congestion, which makes it difficult to apply to the chest for a long time. If your baby has a stuffy nose, an upright breastfeeding position may be more comfortable, so don't be afraid to try different breastfeeding positions.

If your baby has a stuffy nose, an upright breastfeeding position may be more comfortable, so don't be afraid to try different breastfeeding positions.

What should I do if my baby is seriously unwell and cannot breastfeed?

Occasionally, if a child feels unwell, they may not have an appetite or the strength to feed. If your baby is not eating well, seek advice from your healthcare provider, nurse practitioner, or lactation consultant to help prevent dehydration.

You may be asked to express milk to feed your baby with a bottle, a Soft Cup*, or other suitable method that requires minimal effort from the baby. Pumping on a regular breastfeeding schedule will also help keep your milk supply stable.

You can express milk with one of our convenient breast pumps, such as the modern electronic Swing Flex** or the Harmony** manual breast pump. Rest assured, freshly expressed breast milk is just as good as breast milk, so your baby will get all the protection and support it needs.

If you have concerns about your baby's health or how much milk they are drinking, see your doctor as soon as possible.

Can I continue to breastfeed if I become ill myself?

You may not want to do this if you feel unwell, but in most cases it is best to continue breastfeeding. If you have a cold, runny nose, diarrhoea, vomiting, or mastitis, continue breastfeeding as normal with your doctor's approval. The baby is unlikely to become infected through breast milk. What's more, the antibodies in your milk will help reduce your baby's risk of contracting the same 13 virus.

“Breastfeeding when sick is not only safe most of the time, but also beneficial. Your baby is the least at risk of catching your upset stomach or cold, as he is already in close contact with you and receives a daily dose of protective antibodies from milk, ”says Sarah Beeson.

If there is a risk of contracting a viral infection by airborne droplets, it is advisable to temporarily switch to expressing breast milk and bottle feeding.

In order not to lose the amount of milk produced when the body is still weakened by the disease, it is best to use the Swing Maxi Flex ** double breast pump, which helps to stimulate lactation, increase the amount of milk (by 18% on average) and increase its fat content (+1% ) 14 .

However, breastfeeding and pumping when sick can be very tiring. You need to take care of yourself so that you can take care of the baby. Try to drink more fluids, eat when you can, and get plenty of rest. Crawl under the covers for a few days and ask family or friends to help care for your baby if possible, so you can put all your energy into recovery.

“Don't worry about your milk supply, it will last. Most importantly, do not stop breastfeeding abruptly so that mastitis does not develop, ”adds Sarah.

Proper hygiene is very important to reduce the risk of spreading the disease. Wash your hands with soap and water before and after breastfeeding and pumping, preparing and eating food, using the toilet and changing diapers. Use a tissue when coughing and sneezing, or cover your mouth with the crook of your elbow (not your palm) if you don't have a tissue handy. Be sure to wash or sanitize your hands after coughing, sneezing, and blowing your nose.

Use a tissue when coughing and sneezing, or cover your mouth with the crook of your elbow (not your palm) if you don't have a tissue handy. Be sure to wash or sanitize your hands after coughing, sneezing, and blowing your nose.

Can I take medication while breastfeeding?

In agreement with the attending physician and compliance with the dosage, certain medications are allowed. 9.10

.

“When talking to a doctor or pharmacist for any reason, always state that you are breastfeeding,” she continues.

What about long-term treatment?

If you are on long-term treatment for diabetes, asthma, depression, or other chronic conditions, the benefits of breastfeeding may outweigh the risks. “Breastfeeding is often possible for almost any disease, with the exception of some very rare conditions,” Sarah says, “you will be very familiar with the drugs you are taking, and during pregnancy you can discuss them with your doctor or other specialist. There is guidance on the safe use of various medicines that all healthcare professionals use.” In any case, you should consult with your doctor.

There is guidance on the safe use of various medicines that all healthcare professionals use.” In any case, you should consult with your doctor.

“I was on high doses of epilepsy medication, but I was still able to breastfeed,” recalls Nicola, a mother from the UK. “I saw a neurologist to ensure my son was safe and to minimize the risk of a seizure. Seizures can happen due to lack of sleep, and I fed day and night, but I took good care of myself, and my husband supported me. It was a positive experience."

What if I have to go to the hospital?

If you need to be hospitalized or urgently hospitalized, there are different ways to continue feeding your baby healthy breast milk so that you can return to normal breastfeeding after you are discharged.

“Express and freeze breast milk so that the caregiver can feed the baby. Practice at home ahead of time and be sure to let your doctors know that you are a breastfeeding mother, both before entering the hospital and while in it, ”recommends Sarah.

“If the baby is very small, you may be allowed to take him with you. Find out if the hospital has a supervising doctor or lactation consultant to contact. This specialist will support you, especially if you are in a general ward. If hospitalization is urgent, warn the doctors that you have a baby so that they take this into account.

Surgery under local or general anesthesia does not necessarily mean that breastfeeding will have to be stopped, or milk will need to be pumped and discarded. By the time you recover from surgery and can hold your baby, the amount of anesthetic in your breast milk will be minimal, so breastfeeding will be safe in most cases. 10 However, it is always best to consult your doctor or attending physician beforehand.

To ensure that the situation of treatment or departure does not affect the baby's diet, it is advisable to create a breast milk bank. This should be done daily by expressing one extra serving and freezing it in the handy, durable Medela Breast Milk Storage Bags. Even stored for several months and then thawed, your carefully prepared milk will still be incomparably healthier than formula.

Even stored for several months and then thawed, your carefully prepared milk will still be incomparably healthier than formula.

For hygienic and easy pumping, use a breast pump with 2-Phase Expression technology for a fast, full flow of milk. For example, the ultra-comfortable Swing Flex** breastpump that adapts to the shape of your breasts and allows you to pump milk in a comfortable position, even lying back on the pillows 15 .

Don't forget to sterilize your breast pump with the Quick Clean microwave bags. Medela milk storage bags do not need to be handled as they are aseptically packaged and ready to use immediately.

Are there times when breastfeeding is not allowed?

In some cases, for the safety of the baby, breastfeeding should be stopped for a while, and instead, milk should be expressed and discarded to maintain milk production until the end of treatment. This includes radiotherapy and chemotherapy for cancer, herpes sores on the chest, and infections such as tuberculosis, measles, or blood poisoning that can be transmitted through breast milk. 11.12 Consult with a qualified professional about your condition to decide whether breastfeeding can continue in such cases.

11.12 Consult with a qualified professional about your condition to decide whether breastfeeding can continue in such cases.

For quality lactation support during this period, you can use the dual electronic breast pump with innovative Flex technology or rent a Symphony Clinical Breast Pump** if possible. A list of cities where you can rent a breast pump can be found on the "Rent a Medela Clinical Breast Pump" page.

Literature

1 Victora CG et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet . 2016;387(10017):475-490. - Victor S.J. et al., "Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms and long-term effects". Lancet 2016;387(10017):475-490.

2 Lönnerdal B. Bioactive proteins in breast milk. J Pediatric Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7. - Lönnerdahl B., "Biologically active proteins of breast milk". F Pediatrician Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7.

F Pediatrician Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7.

3 Australian Breastfeeding Association [Internet]. Topical treatment with breastmilk: randomized trials. [ cited 2018 Apr 4]. Available from https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au - Australian Breastfeeding Association [Internet]. "Topical treatment with breast milk: a randomized trial". [cited 4 April 2018] See article at https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au

4 Ho JCS et al. HAMLET–A protein-lipid complex with broad tumoricidal activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482(3):454-458. - Ho J.S.S. et al., "HAMLET - a protein-lipid complex with extensive antitumor activity". Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2017;482(3):454-458.

5 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clin Transl Immunology . 2013;2(4): e 3. - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

Clin Transl Immunology . 2013;2(4): e 3. - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

6 Hassiotou F, Hartmann PE. At the dawn of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells . Adv Nutr . 2014;5(6):770-778. - Hassiot F, Hartmann PI, "On the threshold of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells." Adv. 2014;5(6):770-778.

7 Ladomenou F et al. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child . 2010;95(12):1004-1008. - Ladomenu, F. et al., "The effect of exclusive breastfeeding on infection protection in infancy: a prospective study. " Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(12):1004-1008.

" Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(12):1004-1008.

8 Hanson LA. Breastfeeding provides passive and likely long-lasting active immunity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 1998;81(6):523-533. — Hanson, L.A., "Breastfeeding provides passive and likely long-term active protection against disease." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81(6):523-533.

9 Hale TW, Rowe HE. Medications and Mothers' Milk 2017. 17th ed. New York, USA: Springer Publishing Company; 2017. 1095 p . — Hale T.W., Rowe H.I., Medications and Breast Milk 2017. 17th edition. New York, USA: Publishing House Springer Publishing Company ; 2017. p. 1095.

10 Reece-Stremtan S et al. ABM Clinical Protocol# 15: Analgesia and anesthesia for the breastfeeding mother, Revised 2017. Breastfeed Med . 2017;12(9):500-506. - Rees-Stromtan S. et al., AVM Clinical Protocol #15: Analgesia and Anesthesia for Nursing Mothers, 2017 edition. Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2017;12(9):500-506.

Breastfeed Med . 2017;12(9):500-506. - Rees-Stromtan S. et al., AVM Clinical Protocol #15: Analgesia and Anesthesia for Nursing Mothers, 2017 edition. Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2017;12(9):500-506.

11 Lamounier JA et al. Recommendations for breastfeeding during maternal infections. J Pediatr 2004;80(5 Suppl ):181-188. - Lamunier J.A. et al., Guidelines for Breastfeeding during Maternal Infectious Diseases. J Pediatrician (Journal of Pediatrics) (Rio J). 2004;80(5 Suppl):181-188.

12 Hema M et al., Management of newborn infant born to mother suffering from tuberculosis: Current recommendations & gaps in knowledge. Indian J Med Res . 2014;140(1):32-39. - Hema M. et al., "Working with the Infant Born to a Mother with Tuberculosis: Current Recommendations and Gaps. " Indian W Med Res. 2014;140(1):32-39.

" Indian W Med Res. 2014;140(1):32-39.

13 Lönnerdal B. Nutritional and physiologic significance of human milk proteins. Am JClin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1537S-1543S. Lönnerdahl B., "Biologically active proteins of breast milk". F Pediatrician Child Health. 2013;49 Suppl 1:1-7

14 Prime et al., Simultaneous Breast Expression in Breastfeeding Women Is More Efficacious Than Sequential Breast Expression, Breastfeed Med. Dec 2012; 7(6): 442–447. Prime DK and co-authors. "During the period of breastfeeding, simultaneous pumping of both breasts is more productive than sequential pumping." Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2012;7(6):442-447.

15 ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine, USA, data on file: NCT03091985. Clinical Research.gov [Internet]. Bethesda MD: National Library of Medicine, USA, data on file: NCT03091985.

Check out the instructions, consult with a specialist

* Ru FSZ 2010/07353 dated 07/19/10

** RU No. FCZ 2010/06525 dated 17/03/2021

FCZ 2010/06525 dated 17/03/2021

9000 9000 9000 9000 9000

000 Myths about breast milk and breastfeeding

MYTH:

REALITY:

MYTH:

Breastfeeding with small breasts or inverted nipples is impossible.

REALITY:

The size of the breast does not matter, what is important is the maturity of the mammary glands, which are finally prepared for feeding during pregnancy. The shape of the nipple can create problems at the beginning of feeding, but over time these features get used to and the difficulties are overcome.

MYTH:

Failure to feed the first child precludes breastfeeding.

REALITY:

Much of the failure to feed is due to the correct sucking technique of the baby. Usually, women have more milk after their second pregnancy, and if the baby suckles well, everything may be fine.

MYTH:

A woman can always determine breast fullness by her feelings, there is no milk in soft breasts.

REALITY:

The feeling of fullness in the breasts always disappears in the normal way in the second or third month of feeding, the breasts become "empty" and decrease in size. This does not mean that there is not enough milk. Just in case, you can track how much the baby gains weight per week. If he adds well, at least 150 grams per week, there is no reason to worry.

This does not mean that there is not enough milk. Just in case, you can track how much the baby gains weight per week. If he adds well, at least 150 grams per week, there is no reason to worry.

MYTH:

Breast milk can be controlled by pumping.

REALITY:

Normal breastfeeding does not require pumping at all. It is absolutely not suitable for self-control, because the child always stimulates the breast more than any device.

MYTH:

In hot weather, give your baby water.

REALITY:

In the first six months of life, a baby does not need anything but breast milk, and he does not need water. Breast milk always contains a sufficient amount of liquid that is well absorbed by the baby. If it is hot, the baby will usually ask for the breast more often, thereby covering the increased need for fluids. Giving your baby extra drinks all the time can interfere with the flow of breastfeeding because the baby's stomach simply won't fit the right amount of breast milk. If the child is offered additional drinks for a long time, this can lead to a decrease in the baby's appetite.

If the child is offered additional drinks for a long time, this can lead to a decrease in the baby's appetite.

MYTH:

The quantity and quality of breast milk can be improved by eating (halvah) or drinking (milk tea).

REALITY:

The quality of breast milk is practically independent of the mother's diet. All the components necessary for the child - water, proteins, carbohydrates and fats - are present in breast milk even when the mother's nutrition is limited. Only the content of water-soluble vitamins (vitamin C and B vitamins) is directly dependent on the mother's diet. Therefore, vegan mothers should make sure that they are getting enough vitamins D and B12, iron, calcium and zinc during breastfeeding. The amount of breast milk directly depends on the needs of the child, and only as much breast milk is produced as needed at the moment. The baby should ask for the breast at least eight times a day and gain an average of 600-800 grams in weight every month.