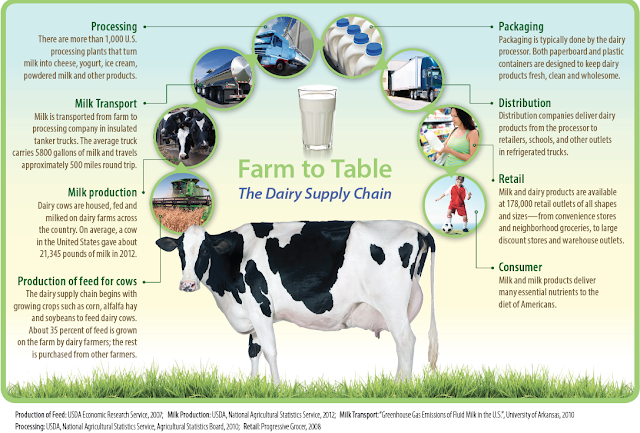

Do all mammals feed their babies milk

Some spiders nurse their young with milk

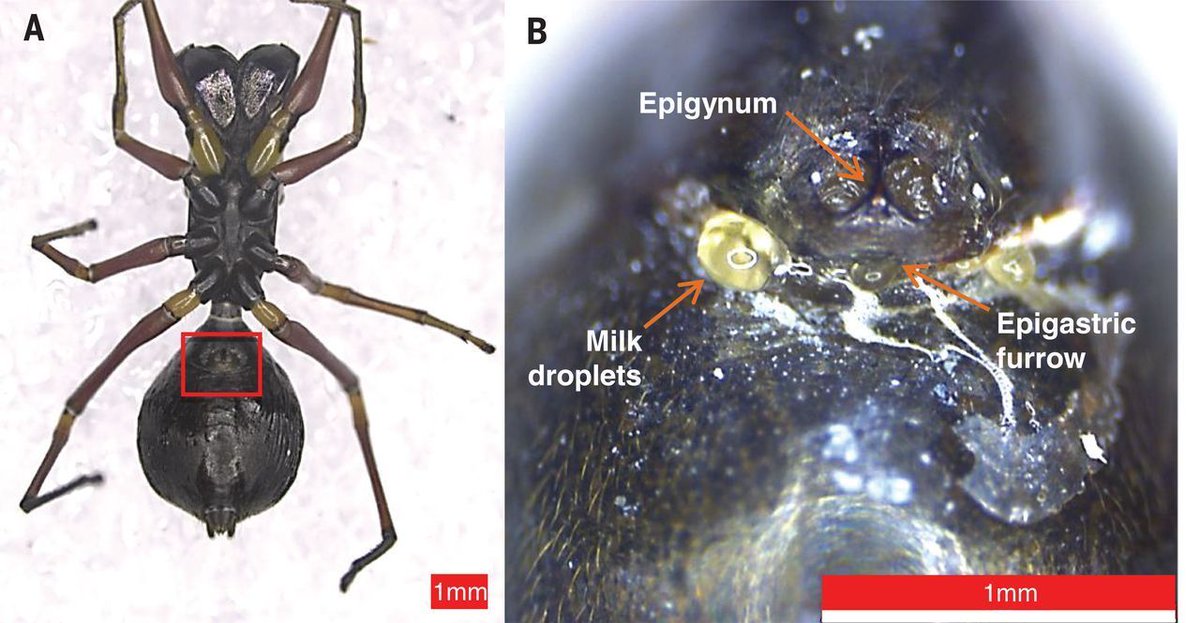

The mimicry is extremely convincing, but this is not an ant. It's an adult female Toxeus magnus jumping spider.

Photograph by Rui-Chang Quan

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

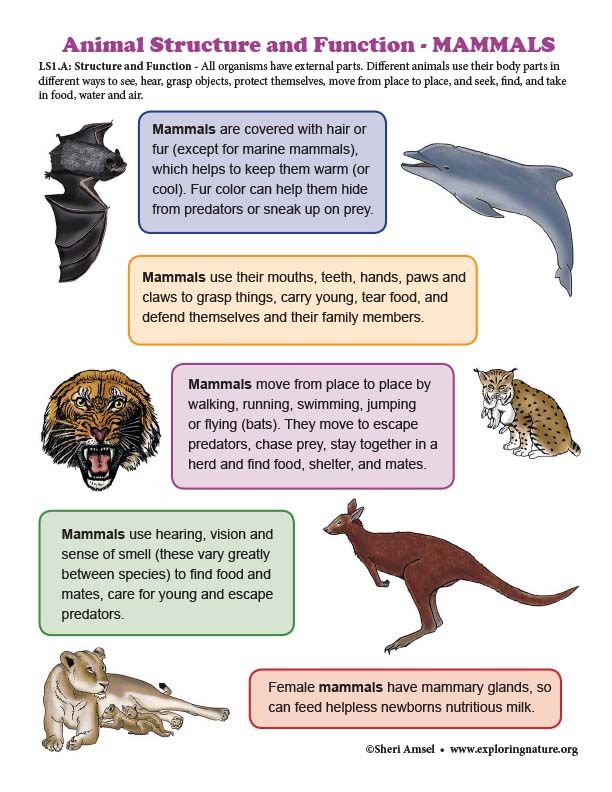

Zebras, bats, and bears do it. So do whales, tigers, and humans. These animals all nourish their newborn offspring with milk. It’s a defining characteristic of what it means to be a mammal.

According to a study published today in the journal Science, a jumping spider native to southeastern Asia does the same thing. Toxeus magnus has been found to suckle its babies with a nutritious fluid secreted by its own body. The liquid contains a solution of sugars, fats, and proteins, so the researchers, led by conservation biologist Rui-Chang Quan of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, are calling it milk.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the researchers found that spiderlings continue drinking their mother’s milk even after reaching sexual maturity. “That's super weird,” says Jonathan Pruitt, an evolutionary ecologist at McMaster University in Canada. “The fact that the parental care extends all the way until female offspring are adults is pretty surprising, eyebrow-raising.”

The evolutionary implications of this behavior are raising eyebrows as well.

A group of spiderlings, three days old, can be seen underneath their mother in their laboratory-based nest.

Photograph by Rui-Chang Quan

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Good parentingThe idea of spider milk, while strange, is actually reasonably consistent with what is known about spider parenting.

Despite their reputation as solitary creatures, various types of spiders have been seen caring for their offspring. “Many female spiders will guard their egg cases and forgo eating while they do that,” says Pruitt, who studies social behavior in spiders. “Some spiders will open their egg cases and allow their offspring to ride around on their backs like [in] The Magic School Bus. ”

”

Other females will even regurgitate pre-digested food for their young, like birds do. Pruitt adds that some spider moms go so far as liquefying their own bodies to be consumed by their young.

But this is the first time spiders have been seen nourishing their offspring with a milk-like fluid.

A female Toxeus magnus prepares her nest in the wild.

Photograph by Rui-Chang Quan

Please be respectful of copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Got milk?“If a loose definition of milk is a nutritive substance that's nourishing young, then it would be considered milk,” confirms Amy Skibiel, a lactation physiologist at the University of Idaho.

“When you think about other non-mammals that produce milk-like fluids, it does become a little less surprising,” Skibiel says. Some birds, such as pigeons, doves, flamingoes, and penguins, produce a substance derived from epithelial cells called “crop milk,” which they feed to their young. And cockroaches are known to secrete a sort of milk, which they use to sustain developing embryos.

And cockroaches are known to secrete a sort of milk, which they use to sustain developing embryos.

In the case of Toxeus magnus, though, Quan and his team argue that the spiders’ behavior is more akin to mammalian lactation. Like many mammals, newly hatched spiderlings are entirely dependent on milk to meet their nutritional needs. In this case, for the first 20 days of the young spiders’ lives.

In one illustrative experiment, the researchers glued shut the spider mothers' epigastric furrow, the egg-laying organ that also secretes milk. The hatchlings all died within their first 11 days.

Nursing teenagersEven after hatchlings are old enough to find food on their own, the researchers discovered that spiderlings will continue to take advantage of their mom's milk for an additional 20 days. And daughters (but not sons) were allowed to continue nursing even after reaching sexual maturity.

At the adolescent and adult stages, being deprived of milk simply forced the spiders to spend more time foraging, indicating that milk was no longer essential for their survival. Still, the researchers suspect that in the wild, milk provisioning could still positively impact survival, since foraging outside the nest increases the risk of predation.

Still, the researchers suspect that in the wild, milk provisioning could still positively impact survival, since foraging outside the nest increases the risk of predation.

But while milk might be essential at certain life stages, it isn't the only thing at work here. Maternal care and milk provisioning appear to work together to ensure the long-term survival of young spiders. In experiments where the mom was allowed to remain in the nest, but was prevented from nursing her young after day 20, spiderlings still had fewer parasites than those from nests in which the mom was removed entirely.

Of the 187 spiderlings researchers observed in 19 different nests, the survival rate for those that received both maternal care and milk was 76 percent. Removing the mother at day 20 reduced the spiderlings’ survival rate to about 50 percent.

Since spider mothers also deposit milk droplets into the nest itself, this suggests that milk might have a function beyond nutrition. “There's still some unanswered questions that would help us determine if this is functionally similar to mammalian lactation,” Skibiel says.

“There's still some unanswered questions that would help us determine if this is functionally similar to mammalian lactation,” Skibiel says.

In mammals, milk probably did not initially evolve for nutrition. Instead, lactation was likely either a means for mothers to jumpstart their infants' immune systems by providing them with antibodies, or a means to keep their eggs moist, as duck-billed platypuses do.

And while the evolution of milk-like fluids outside of the mammal family remains rare, it's also unlikely that this is the only spider species to have done so. “The more I think about it, there is actually a pretty good chance this is happening all over the place,” Pruitt says. “Out of 50,000 described species of spiders, you can bet your boots this isn't the only one that does it.”

Read This Next

Here’s where to see ‘the way of water’ in real life

- Travel

Here’s where to see ‘the way of water’ in real life

The largest of the Cook Islands, Rarotonga offers an up-close look at an ancient seafaring culture—and, in many ways, resembles the fictional world of the Avatar sequel.

This museum is trash—literally

- History & Culture

This museum is trash—literally

Plastic revolutionized our lives—but at a great cost to the planet. This virtual museum offers an unsettling look at the durability of our garbage.

Subscriber Exclusive Content

Why are people so dang obsessed with Mars?

How viruses shape our world

The era of greyhound racing in the U.S. is coming to an end

See how people have imagined life on Mars through history

See how NASA’s new Mars rover will explore the red planet

Why are people so dang obsessed with Mars?

How viruses shape our world

The era of greyhound racing in the U.S. is coming to an end

See how people have imagined life on Mars through history

See how NASA’s new Mars rover will explore the red planet

Why are people so dang obsessed with Mars?

How viruses shape our world

The era of greyhound racing in the U.

S. is coming to an end

S. is coming to an endSee how people have imagined life on Mars through history

See how NASA’s new Mars rover will explore the red planet

See More

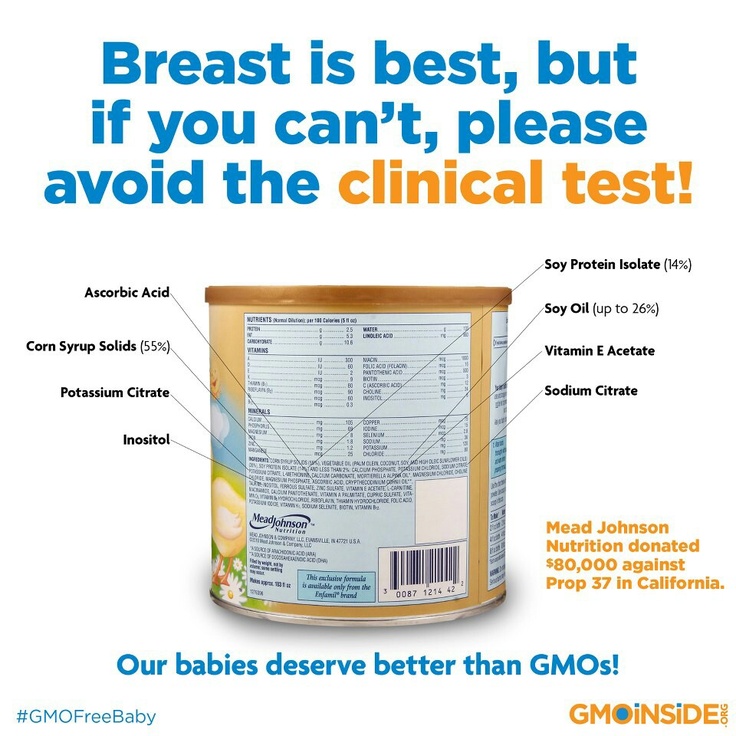

10 Animals That Make 'Milk' and Aren’t Mammals

It’s not just mammals that “got milk.” Though we typically think of milk as the lactose-containing liquid that comes from mammary glands, scientists are discovering more species that give their babies a boost by making special substances for them. And these sort-of milks aren’t just nutrient rich, some contain stuff that help babies fight infection or establish a gut microbiome, just like mammalian milk. It’s proof that the animal world still has surprises left to discover.

(Credit: Fercast/Shutterstock)

Pigeons

Both female and male pigeons produce a nutritious white liquid from a food storage pouch in their throat, called a crop. Their squabs eat nothing but this “crop milk” for the first three days after hatching, then the adults start introducing them to pigeon food, though they continue to get crop milk until they’re about 28 days old. Like mammalian milk, scientists have found that crop milk contains antibodies from the parents, activates genes involved in the immune system, and contributes to the gut microbiome. Also, the hormone that stimulates milk production in female mammals, called prolactin, is also what promotes milk production in both male and female pigeons.

Like mammalian milk, scientists have found that crop milk contains antibodies from the parents, activates genes involved in the immune system, and contributes to the gut microbiome. Also, the hormone that stimulates milk production in female mammals, called prolactin, is also what promotes milk production in both male and female pigeons.

(Credit: vladsilver/Shutterstock)

Emperor Penguins

For Antarctica’s emperor penguins, it’s the males who spend the harsh winter incubating an egg, and they’re also the ones who make a fatty liquid in their crop. The males regurgitate their crop milk to feed newly hatched chicks. The females don’t make milk, but bring food to the chick instead.

(Credit: Ondrej Prosicky/Shutterstock)

Flamingos

Male and female flamingos make crop milk, too, and regurgitate it into their chicks’ mouths for up to six months. The crop milk is bright red due to the presence of a red-colored antioxidant called canthaxanthin, which also helps the chicks turn from white to pink. Meanwhile, the parent flamingos lose their pink color and become more white during the breeding season as they give up nutrients.

Meanwhile, the parent flamingos lose their pink color and become more white during the breeding season as they give up nutrients.

(Credit: Jaco Visser/Shutterstock)

Tsetse Flies

Tsetse flies are biting insects that can spread a parasitic organism that causes human sleeping sickness. And tsetse flies, unlike most insects, give birth. The larva grow inside the female tsetse fly’s uterus, which has glands that secrete a milk-like substance to sustain the larva. Like mammalian milk, the nutritive properties of this “milk” change as the larva grows.

(Credit: SnelsonStock/Shutterstock)

Pacific Beetle Cockroaches

Pacific beetle cockroach larva, like tsetse fly larva, grow inside their mother where they consume a liquid that scientists say is one of the most calorie-rich “milks” on the planet. (Hooded seals are considered to have the most calorie-packed milk—the pups drink their mother’s milk for only four days and gain about 50 pounds on it!).

(Credit: Chen/Science)

Jumping Spiders

Female southeast Asian jumping spiders make a nutritious substance for their spiderlings, which depend on it to survive. The spiderlings crowd around their mother, much like a group of puppies or piglets, to feed on this “milk” from her epigastric furrow (where eggs also come out). The “milk” contains four times more protein than cow’s milk, and sustains them for about 20 days, at which point they hunt food on their own.

The spiderlings crowd around their mother, much like a group of puppies or piglets, to feed on this “milk” from her epigastric furrow (where eggs also come out). The “milk” contains four times more protein than cow’s milk, and sustains them for about 20 days, at which point they hunt food on their own.

(Credit: Andrey Armyagov/Shutterstock)

Discus Fish

Colorful Amazonian discus fish make a milk-like mucus to feed their babies (fry). Both parents produce the slime from their skin, which is not only nutrient rich, it also contains beneficial bacteria that colonize and establish the fry’s gut microbiome. The fry feed on it, and nothing else, until they’re about three weeks old. Then the parents start swimming away for longer and longer periods so the young fish can start investigating other foods, like algae and small worms.

(Credit: beachbassman/Shutterstock)

Caecilians

Caecilians are tropical amphibians that look like large worms or slimy snakes. Some caecilian species give birth, and the young growing inside the mother eat the cells lining the uterine tube. But in other caecilian species, the outer layer of the mother’s skin transforms into a nutrient-rich snack for the offspring, which peel off and eat the skin with special teeth. While it’s not a liquid, it serves a similar function as milk.

But in other caecilian species, the outer layer of the mother’s skin transforms into a nutrient-rich snack for the offspring, which peel off and eat the skin with special teeth. While it’s not a liquid, it serves a similar function as milk.

(Credit: Ramon Carretero/Shutterstock)

Great White Sharks

Great white shark pups grow inside female sharks’ uterus, but because they don’t have an umbilical cord to get nutrients like mammals do, the uterus sheds a milky substance to sustain the pup before it’s born. (A few shark species do have umbilical cords and, after they’re born, bellybuttons to prove it!).

(Credit: Hussmann/Shutterstock)

Nematodes

A nematode, a microscopic soil-dwelling roundworm, doesn’t have a heart or blood, and their entire body only has about 1,000 cells (a human body has about 30,000,000,000,000 cells). Yet in 2020, scientists discovered that one species of nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans) releases a nourishing yolk protein from their vulva to help their offspring grow. In the process of making this superfood, the nematode mothers’ bodies are destroyed—they die to support their young.

In the process of making this superfood, the nematode mothers’ bodies are destroyed—they die to support their young.

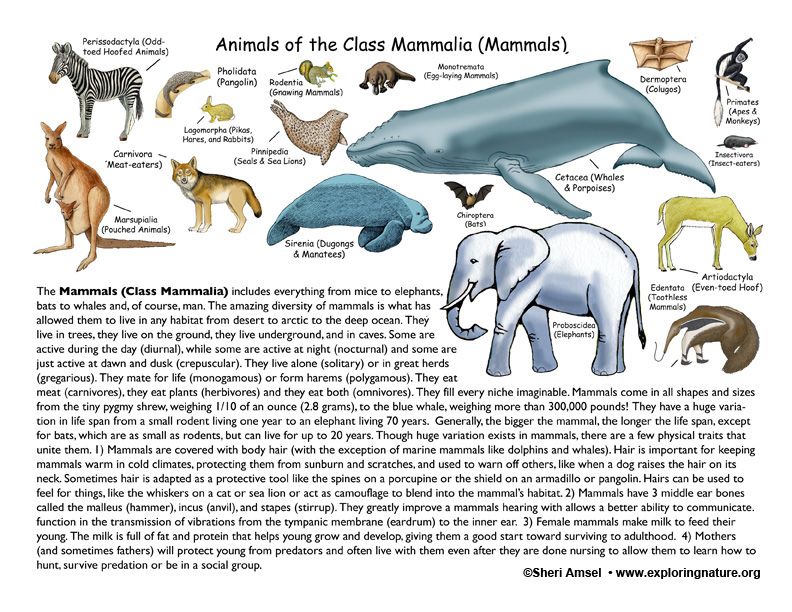

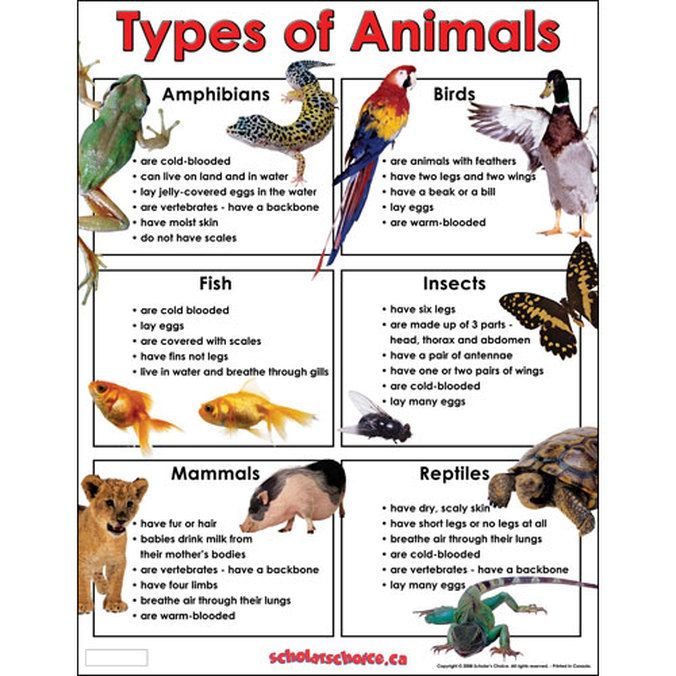

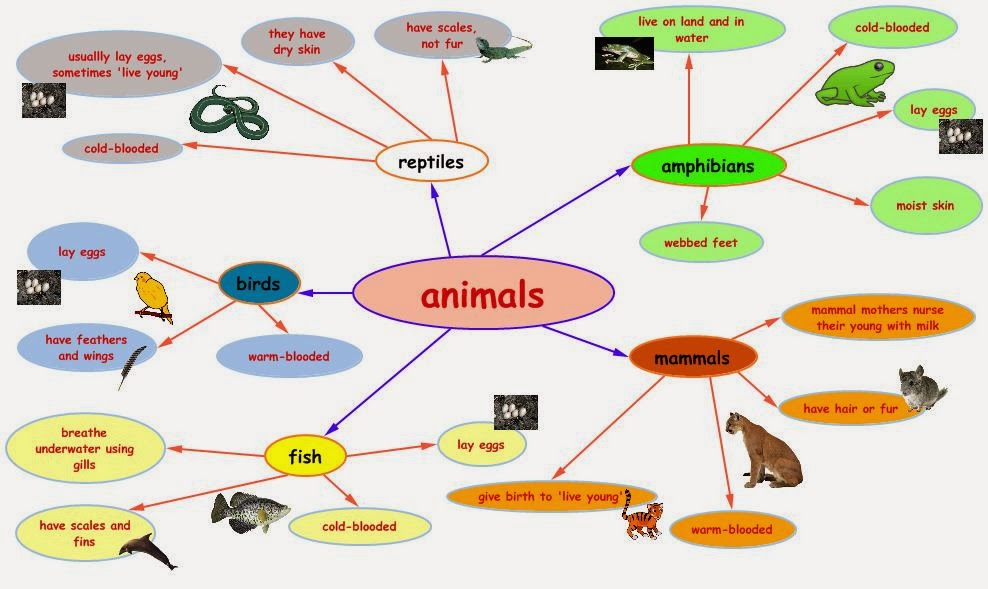

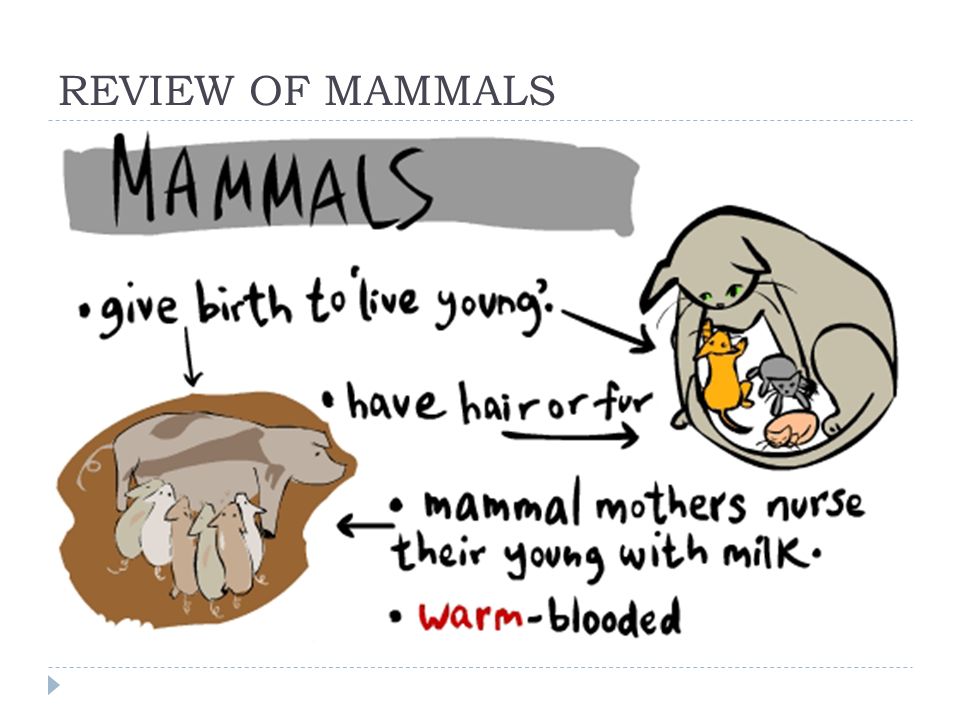

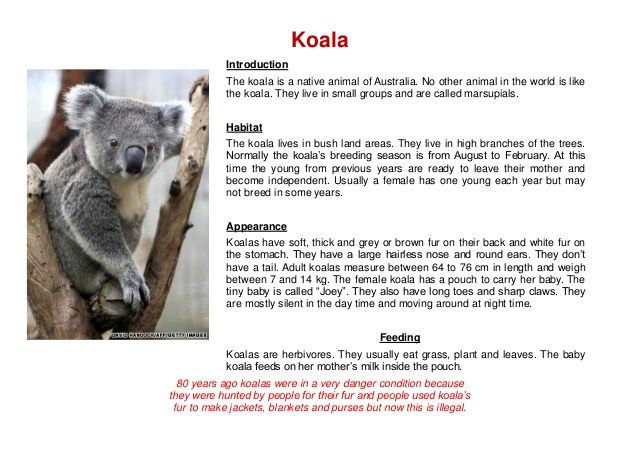

Mammals - Wildlife

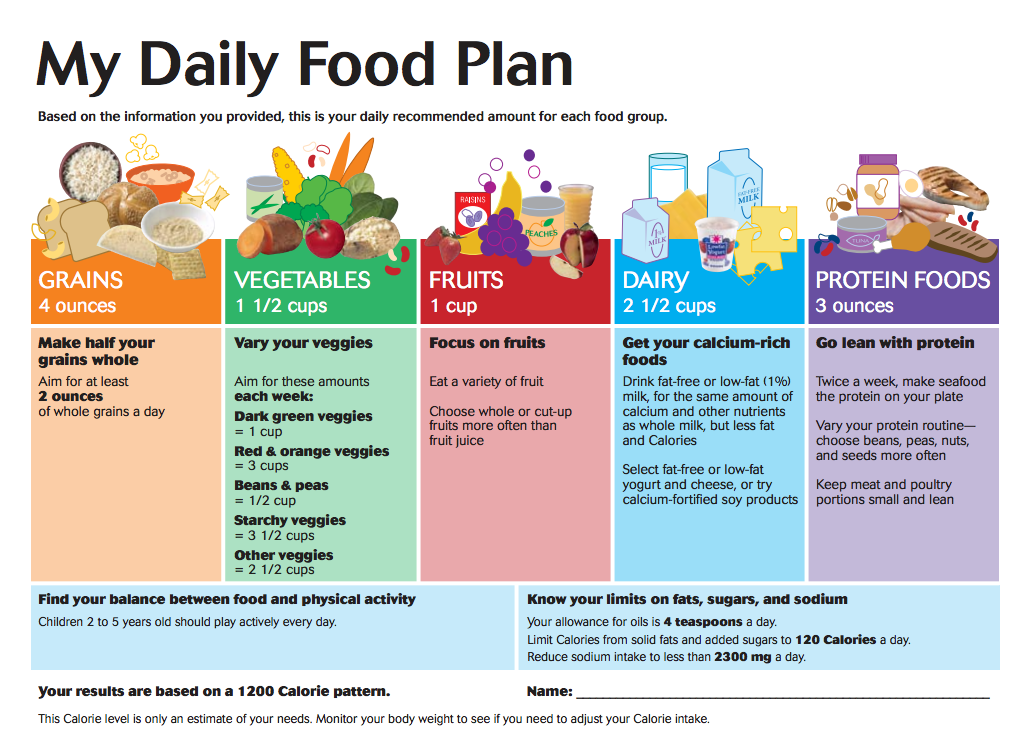

All mammals are warm-blooded, breathe air, are covered with hair, have a backbone, feed their young with milk. Their brains are larger and more complex than those of all other animals. Mammals, of course, are characterized by high adaptability.

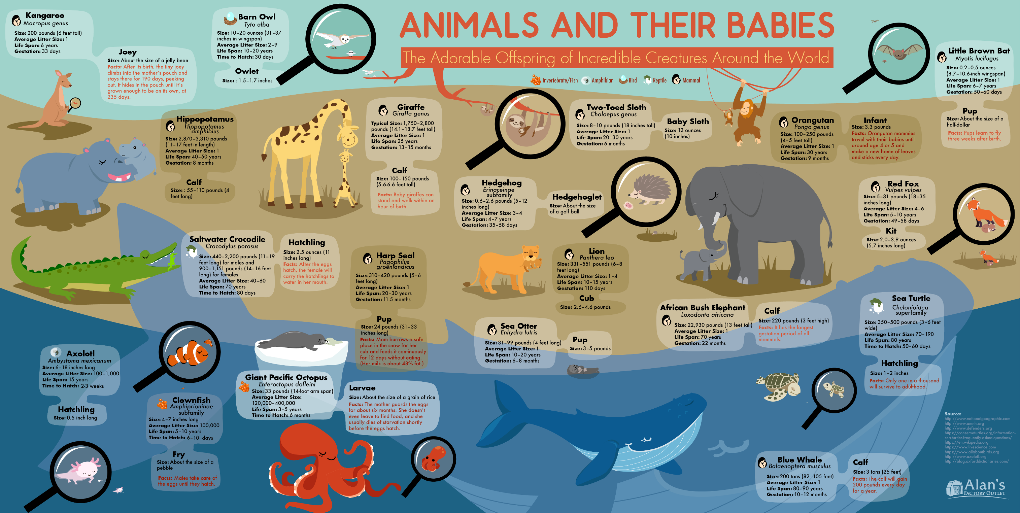

Animals of this class spread throughout the planet from one pole to the other. They occupied the air, water bodies, and land. Mammals range in size from the 30-meter blue whale, the largest animal on Earth, to the tiny shrew, which is less than 10 cm long.

The typical mammal is a nonexistent ideal. In size, the animals vary from a huge whale to a tiny shrew. They live everywhere - from the sky (bats) to the sea (whales, walruses). Anteaters feed on ants, and walruses feed on clams and crabs, some rodents are omnivores. Kangaroos hop, manatees swim, monkeys climb, colewings glide from branch to branch. Horns, trunk, armor - mammals are magnificent in their diversity.

Horns, trunk, armor - mammals are magnificent in their diversity.

Reproduction of mammals

Of the more than 4000 species of mammals, the largest group is placental, in which the fetus develops in the womb on a special organ - the placenta. This group includes lions, elephants, mice, horses, hippos and many others. In marsupial mammals, young are born underdeveloped; their further growth occurs in a special bag on the mother's belly. Examples are kangaroos and opossums. nine0003

Echidnas and platypuses lay eggs. Such mammals are called monotremes. They live in Australia and New Guinea. The cubs hatched from the egg outside the mother's body are also fed with milk, but the females do not have nipples, the mammary glands open simply in pores, and the babies have to lick the droplets of milk flowing down the wool.

Mother's milk in different animal species

All mammals feed their young with milk, but its composition is far from the same. The content of fat, protein, sugar and water in milk is different depending on the species, environmental conditions and age of the cub. Immediately after giving birth, the seal produces unusually nutritious milk, its fat content is about 53%. On such a diet, the seal quickly builds up a heat-insulating layer of subcutaneous fat, which is necessary for life in cold water. A long-faced seal pup gains about 2 kg daily, and when the mother stops feeding him at the age of only 2 weeks, his weight approaches 45 kg. nine0003

Immediately after giving birth, the seal produces unusually nutritious milk, its fat content is about 53%. On such a diet, the seal quickly builds up a heat-insulating layer of subcutaneous fat, which is necessary for life in cold water. A long-faced seal pup gains about 2 kg daily, and when the mother stops feeding him at the age of only 2 weeks, his weight approaches 45 kg. nine0003

Whales and other mammals that never leave the water also have high fat milk. Kittens gain almost 90 kg daily. A baby blue whale doubles its original weight just a week after birth. It takes 47 days for a domestic cow and 60 days for a horse.

Both the Bactrian camel and the Kangaroo Leaper live in arid places, but the camel's milk is 87% water, and the jumper's milk is only 50%. This is probably due to differences in the circadian rhythm. The kangaroo jumper is active only at night, while the camel is active during the day, and its cub needs more fluid. nine0003

How do animals talk to each other?

It is often believed that speech is unique to humans, but some scientists believe that the complex sound signals of a part of cetaceans, such as dolphins, are also language. According to researchers teaching sign language to great apes, the concept of language should not be anthropocentric. The language, according to representatives of this direction, should be recognized as the ability of animals to transmit information and communicate.

According to researchers teaching sign language to great apes, the concept of language should not be anthropocentric. The language, according to representatives of this direction, should be recognized as the ability of animals to transmit information and communicate.

In any case, in order to transmit information, it is not necessary to speak orally. Animals communicate using sounds, touch, visual information, and smells. The barking of a prairie dog, the pushing of a mother's udder by a calf, the raised tail of a wolf, the marking of the area by dikdik with odorous secretions of the infraorbital gland - all these are means of transmitting signals to their own kind, and these signals are as unambiguous as the corresponding human phrases: "Beware of danger!", "I I want to eat”, “Here I am in charge”, “This is my territory”. nine0003

Joint actions are mainly characteristic of animals living in groups - wolves, hyenas, wild dogs, baboons, prairie dogs, chimpanzees and many others. When a pack of wolves attacks musk oxen, they defend themselves in a circle, put out their horns and hide cows and calves in the middle of this human shield. The lionesses hunt for the entire pride, often helping each other to drive and kill the prey, and also take care of the cubs together. Dolphins collectively hunt, and when one of the group members is injured, the rest support him on the surface so that he can breathe. Sometimes these extremely intelligent animals help people who are in trouble or shipwrecked. nine0003

When a pack of wolves attacks musk oxen, they defend themselves in a circle, put out their horns and hide cows and calves in the middle of this human shield. The lionesses hunt for the entire pride, often helping each other to drive and kill the prey, and also take care of the cubs together. Dolphins collectively hunt, and when one of the group members is injured, the rest support him on the surface so that he can breathe. Sometimes these extremely intelligent animals help people who are in trouble or shipwrecked. nine0003

some spiders feed their young with milk // Look

-

Profile

Spiders and cobwebs November 30, 2018, 16:57 November 30, 2018, 17:57 November 30, 2018, 18:57 November 30, 2018, 19:57 November 30, 2018, 20:57 November 30, 2018, 21:57 November 30, 2018, 22:57 November 30, 2018, 23:57 December 1, 2018, 00:57 December 1, 2018, 01:57 December 1, 2018, 02:57

-

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

nine0003

nine0003 -

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

- nine0002 Photo by Zhanqi Chen et al.

-

Photo by Science/AAAS.

nine0041 -

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

-

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan. nine0003

-

Photo by Zhanqi Chen et al.

- nine0002 Photo by Science/AAAS.

It turned out that some female spiders feed their young with a nutrient liquid, which the authors of a recent work called milk. But scientists were surprised not so much by this as by the fact that the mother feeds offspring for quite a long time.

But scientists were surprised not so much by this as by the fact that the mother feeds offspring for quite a long time.

On a summer night in 2017, scientist Chen Zhanqi made a curious discovery in his laboratory in China's Yunnan province. He noticed on the belly of the mother a young jumping spider of the species Toxeus magnus (arthropods lived in an artificial nest). Such a scene reminded the researcher of young mammals sucking their mother's milk.

Further research by Chen and his colleague Quan Rui-Chang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences confirmed that female jumping spiders do produce nutrient fluid for their young. The authors of the work called it milk.

Mammals are known to take care of their offspring for a long time. Female animals feed their babies with milk (it took about two and a half years for an ancient person). nine0003

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

Such care, simultaneous milk feeding and long-term care, is an unheard-of generosity for the world of insects, arthropods and other invertebrates. At least that's what it used to be.

At least that's what it used to be.

The heroes of a recent study are female T. magnus laying between two and 36 eggs at a time. After the young are born, the mother begins to deposit tiny milk droplets around the nest, which Chen and his colleagues observed in the lab.

Spider milk surprised experts a lot. Arthropods provide food for their offspring in different ways: belching, unfertilized eggs, or, in extreme cases, their own flesh, but not milk ...

Experts analyzed the liquid. It turned out that it contains fats, sugars and proteins, the content of which is four times higher than in cow's milk.

What happens to the spider family next? In the first couple of days, the spiderlings ate droplets of milk, scientists write. Later, the young were fed with nutrient fluid directly from the mother's epigastric sulcus. nine0003

Photo by Zhanqi Chen et al.

On the 20th day, young arthropods began to hunt outside the nest, while they continued to supplement their diet with mother's milk. This continued until reaching puberty (after another 20 days).

This continued until reaching puberty (after another 20 days).

As scientists say, when the spiderlings grew up, the mother began to attack the males if they returned to the nest, but she treated the females more calmly. Perhaps this behavior helps prevent inbreeding.

When Chen tried to paint over the epigastric sulcus of the female spider to cut off the milk supply, all the spiders younger than 20 days old died. nine0003

If he removed the mother from the nest, the "teenager" spiders grew more slowly and left the nest early. In addition, they were more likely to die before reaching adulthood.

Scientists say that other species of spiders also stay close to their young for several days after birth, but they rarely feed them in this way.

Some amphibians and other invertebrates are known to lay similar trophic eggs to feed their young, the scientist notes. Although animals do this only when the cubs are still very small. nine0003

What is interesting in this study is not even that spiders of the species T. magnus produce milk, but how long they feed it to their young.

magnus produce milk, but how long they feed it to their young.

Such long-term parental care (as in jumping spiders) occurs only in some long-lived social vertebrates: humans or elephants, for example, notes Rui-Chan.

According to him, the discovered example of maternal care indicates that invertebrates have also developed this feature.

According to behavioral ecologist Nick Royle of the University of Exeter, who was not involved in the study, the results help "improve understanding of the evolutionary origins of complex forms of parental care."

In his opinion, such care often signals greater than usual needs of offspring (for example, when there is a shortage of food for babies). In this case, it really makes sense for mothers to become especially caring parents. nine0003

Such behavior requires additional efforts and resources from females, and therefore it appears, most likely, only in extreme conditions.