Feeding baby after vaccination

COVID vaccines and breastfeeding: what the data say

A mother breastfeeds her newborn at a hospital in Belgium.Credit: Francisco Seco/AP/Shutterstock

Molly Siegel had long awaited a COVID-19 vaccine. As an obstetrician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, she regularly saw pregnant people with COVID-19, and knew that the vaccine was the best way to protect herself, her family and others in her workplace. But with a seven-month-old baby at home who was still breastfeeding, she felt hesitant.

Understandably so. Following established norms for clinical trials, pregnant and breastfeeding people were not included in any of the trials for COVID-19 vaccines. So, as health systems around the world began to vaccinate eligible adults, scores of lactating people were left to make their decision in the dark.

“I certainly was frustrated that there weren’t studies on the vaccine in pregnant and lactating women — that as a group, they were excluded from the research,” Siegel says. “It made it really hard to know, as both the patient and the provider, how to think about the vaccine.”

Still, Siegel could not see any plausible risk to her breast milk (she knew that COVID-19 vaccines contain no live virus, for instance), and focused on the benefit of protecting herself and everyone around her. So she got the shot. Then, she donated samples of her breast milk to researchers who would analyse its contents in one of the first such studies.

Now, thanks to Siegel and other participants, scientists are beginning to understand the effects of COVID-19 vaccines on breast milk, and their preliminary results should come as welcome news to the more than 100 million lactating people across the world.

Scientists have so far looked only at the vaccines made by Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna, and have not detected the vaccines in breast milk. What they have found are antibodies, produced by mothers in response to inoculations, to the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

“We’re really happy to have something good to hang our hat on,” says Stephanie Gaw, a perinatologist at the University of California, San Francisco. “The studies are small, they’re still early, but very positive.” Now, researchers want to know whether those antibodies can provide babies with at least partial protection against COVID-19.

“The studies are small, they’re still early, but very positive.” Now, researchers want to know whether those antibodies can provide babies with at least partial protection against COVID-19.

Throughout the pandemic, pregnant people and new mothers have been faced with a slew of concerns and questions about the coronavirus.

One trend that became clear early on is that pregnant people diagnosed with COVID-19 are more likely to be hospitalized than are those of the same age who are not pregnant. That could be because the body is already working hard — the growing uterus pushes upwards, reducing lung capacity, and the immune system is suppressed so as not to harm the baby. Those factors don’t disappear the day a baby is born. As such, some obstetricians suspect that lactating individuals are also susceptible to severe COVID-19.

That conclusion might encourage breastfeeding mothers to get vaccinated, but scientists weren’t sure how they would respond to the vaccines, because little is known about the period of lactation.

So Kathryn Gray, a maternal–fetal medicine specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and her colleagues decided to test how well the Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna vaccines work in this group. They recruited 131 participants who were about to receive either vaccine and who were lactating, pregnant or neither, and found that the lactating individuals (which included Siegel and 30 others) generated the same robust antibody response as did those who were not lactating1. In other words: the vaccine is just as beneficial for breastfeeding mums.

Scientists studying breast milk samples have discovered that they carry antibodies from vaccination.Credit: Remko de Waal/ANP/AFP via Getty Images

A second study by Gaw and her team, posted on the preprint server medRxiv, agrees2. The team drew blood from 23 lactating participants and found that antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 increased after their second dose.

But for many parents, the looming question — as Siegel asked herself — was whether a COVID-19 vaccine would harm a nursing infant. After all, some medications are not recommended during lactation because they pass through breast milk to infants. Nursing mothers are advised against taking high doses of aspirin, for example; even after low doses, mothers are warned to monitor the infant for signs of bruising and bleeding. Some vaccines are off limits, too. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises nursing mothers against receiving the yellow-fever vaccine, which involves a live, weakened form of the virus, on the off-chance that an infection passes to the infant.

After all, some medications are not recommended during lactation because they pass through breast milk to infants. Nursing mothers are advised against taking high doses of aspirin, for example; even after low doses, mothers are warned to monitor the infant for signs of bruising and bleeding. Some vaccines are off limits, too. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises nursing mothers against receiving the yellow-fever vaccine, which involves a live, weakened form of the virus, on the off-chance that an infection passes to the infant.

Because of such cases, some pharmacists and vaccine administrators have been urging nursing mothers to discard their breast milk after they are vaccinated.

Pregnancy and COVID: what the data say

“I think that clearly shows ignorance and a lack of understanding,” says Kirsi Jarvinen-Seppo, an immunologist at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York. “There seems to be an awful amount of misinformation out there on all levels. ”

”

Unlike the yellow-fever vaccine, COVID-19 vaccines do not carry a risk of igniting an active infection. In addition, COVID-19 vaccines are extremely unlikely to cross into breast milk. The fragile messenger RNA used in the Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, for example, is designed to break down so quickly that it should never leave the cells where it was injected — let alone get into the bloodstream and then the breast. In fact, researchers don’t expect that any of the current vaccines will be excreted into breast milk.

To that end, the World Health Organization recommends that mothers continue to breastfeed after vaccination. In addition, the CDC and the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation issued statements shortly after the first vaccines were authorized in both countries. These noted that no safety concerns had been identified from the available data, so lactating people could choose to be vaccinated.

“It’s sort of a backwards way of recommending it,” argues Christina Chambers, a paediatrician at the University of California, San Diego, and the Rady Children’s Hospital. “The foundation is that there’s no reason to avoid it, which is a dilemma.”

“The foundation is that there’s no reason to avoid it, which is a dilemma.”

So Gaw and her colleagues ran a safety check. In a small study3, her team looked at breast milk samples from six participants up to two days after they received the Pfizer–BioNTech or Moderna vaccine, and found no trace of the mRNA in either case. (The group is now scouring a larger number of milk samples for different components of the vaccine, and expanding their study to include all the available COVID-19 vaccines in the United States.)

Liquid goldThere is one type of particle that scientists are eager to see in breast milk following a vaccine: COVID-19 antibodies.

Researchers have long known that newborn babies don’t effectively produce antibodies against harmful bacteria and viruses; and it can take three to six months for this kind of protection to kick in. To help in those early days, a mother’s breast milk overflows with antibodies capable of staving off potential threats.

“It’s specifically designed by the mother, and by Mother Nature, to provide the child with the child’s first vaccine,” says Hedvig Nordeng at the University of Oslo, who specializes in medication use and safety in pregnancy and lactation. “Breast milk by itself is more than nutrition, breast milk is medicine.”

The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines — and what it means for other diseases

In the mother, immune cells called B lymphocytes (or B cells) constantly produce antibodies. Then, once lactation begins, the mammary glands send out a chemical signal that draws these B cells to the breast — where they park in the glands and produce thousands of antibodies per second, ready to move into the breast milk in huge quantities. But unlike molecules from medications, coffee and alcoholic drinks, which are so small they can pass into the breast milk on their own (although at diluted levels), antibodies are too large to do so. Instead, receptors on the surface of the milk ducts grab the antibodies and package them in protective, fluid-filled bubbles that allow them to pass safely through the milk-duct cells and into the milk on the other side4.

“This process is so magical,” says Galit Alter, an immunologist and virologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, who worked on Gray’s study.

What happens once antibodies reach the baby, however, is more mysterious. Antibodies in the breast milk do not make it into a baby’s bloodstream, but coat the mouth, throat and gut before they’re ultimately digested4. Nonetheless, these antibodies seem to provide protection. It could be that they work at the body’s entrances to fend off infection before it takes root.

Not all babies are raised on breast milk, but studies have shown that babies who exclusively breastfeed for their first six months have far fewer middle-ear infections than those who are breastfed for a shorter time, or not at all5. They also have a lower risk of respiratory-tract infections6. And lactating mothers who receive the influenza vaccine (and therefore transmit those protective antibodies to their infant through breast milk) provide some protection to babies who are too young to receive the shot7.

The same could be true for COVID-19 antibodies. Early this year, researchers found that breast milk from people who recover from the virus similarly oozes with antibodies8. And a smattering of small studies, many not yet peer reviewed, have found antibodies in breast milk from people who received the vaccine1,2,9–12 (see ‘Breast-milk benefits’).

Source: Ref. 12

When Gray and her colleagues, for example, checked the blood and the breast milk of lactating mothers who had received a COVID-19 vaccine, they found high levels of COVID-19 antibodies in every sample1.

“It’s very nice after this past year to have a tiny bit of good news,” says paediatric immunologist Bridget Young at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

And it’s a particularly exciting finding given that babies are not currently eligible to receive any of the available vaccines (although both Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna have started trials of their COVID-19 vaccines in children as young as six months).

Whereas COVID-19 is often mild in younger populations, babies less than two years of age who contract the disease are more likely to be hospitalized than older children are8. That’s thought to be because the bronchioles, the passageways that deliver air to the lungs, are much smaller in babies. In addition, babies and children can develop a severe illness known as MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children), in which different parts of the body become inflamed after the child contracts COVID-19.

Milk mysteriesOne of the big unknowns now is how much protection babies receive from breast milk.

To begin, scientists aren’t sure whether these antibodies are actually functional — meaning that they would kill the virus that causes COVID-19 if they came into contact with it. But early research is promising. Last year, a team in the Netherlands collected antibodies from the breast milk of people with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and found that the samples could neutralize the virus in the laboratory13. A month later, Young, Jarvinen-Seppo and their colleagues posted similar findings, which were subsequently published14.

A month later, Young, Jarvinen-Seppo and their colleagues posted similar findings, which were subsequently published14.

Both teams are currently conducting the same experiment with vaccine-induced antibodies, following a study by scientists in Israel10 suggesting that antibodies created after vaccination could stop the virus infecting cells. The authors of that study predict that these antibodies should protect the baby, says Yariv Wine, an immunologist at Tel Aviv University and a co-author of the paper.

But this can happen only if the antibodies persist. Scientists don’t yet know how long vaccinated people will continue to make COVID-19 antibodies, but evidence indicates they do so for a considerable time; one study of 33 people15 suggests that antibody production in adults given the Moderna vaccine continues for at least 6 months. That could mean that babies will continue to receive some protection from their mothers, as long as they continue nursing — although antibody concentrations in breast milk do drop over time4.

And that constant replenishment is key. Scientists suspect that antibodies are digested in the baby’s gut after hours to days. That means their partial immunity will probably disappear once breastfeeding has ceased. It also suggests that giving breast milk to older children (as many vaccinated mothers have discussed in online forums) probably won’t give them partial immunity — at least not for long.

But even for babies who are exclusively breastfed, clinicians urge mothers to continue to follow public-health strategies when they have visitors. “Anyone who’s handling the baby in close contact really should be vaccinated and should be masked,” says Andrea Edlow, a maternal–fetal medicine specialist at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, who worked on the study with Gray.

Luckily, more data are on the way. Gray and her team will be tracking their participants, including Siegel and others, for a full year (although the details are still being discussed). Gaw’s team at the University of California, San Francisco, is planning to assess the overall health and rate of infections of babies while they’re being breastfed — the million-dollar question at the moment. The two studies pitting vaccine-induced antibodies against the virus in a Petri dish should offer another answer to this question.

Gaw’s team at the University of California, San Francisco, is planning to assess the overall health and rate of infections of babies while they’re being breastfed — the million-dollar question at the moment. The two studies pitting vaccine-induced antibodies against the virus in a Petri dish should offer another answer to this question.

Scientists are also working to analyse the antibodies in further detail. Chambers and her colleagues at the University of California, San Diego, for example, currently receive milk samples from roughly 40 participants per day; they also plan to follow the babies’ growth and development.

Nonetheless, the results so far are promising enough that most experts would urge nursing mothers to get their shots. “If I had an itty-bitty baby right now, I would not take the risk — I would not wait,” Alter says. “If you can empower your kid with immunity, I wouldn’t even question it.”

Vaccines - La Leche League International

Deutsche: Impfungen

Skip to: Vaccines

Skip to: Vaccines and the breastfeeding parent

Skip to: COVID-19 Vaccines and breastfeeding

Skip to: Vaccines and the breastfed baby

Skip to: Resources

You may have questions about the compatibility of vaccines and breastfeeding. We encourage families to consult with their healthcare provider and any relevant Government guidance for information to help them make an informed decision regarding vaccination.

We encourage families to consult with their healthcare provider and any relevant Government guidance for information to help them make an informed decision regarding vaccination.

This post provides information about vaccines a nursing mother or parent may need, and some ways to comfort a baby who has received a vaccination.

VACCINES AND THE BREASTFEEDING PARENTFor parents who may need vaccines during the course of the breastfeeding relationship, questions about which vaccines can be administered while maintaining breastfeeding can arise. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “With rare exceptions, maternal immunization does not create any problems for breastfeeding infants[…][2] “

Organizations such as The Infant Risk Center at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center[3], MotherToBaby, a service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists[4], and The Breastfeeding Network[5] in the United Kingdom can provide information about specific substances and breastfeeding to share with your healthcare provider. The e-lactancia website offers information about medications in English and Spanish[6]

The e-lactancia website offers information about medications in English and Spanish[6]

There are further resources in multiple languages in our article on Medications here.

The US based Center for Disease Control (CDC) has issued the guidelines linked here with regards to receiving vaccines while breastfeeding.

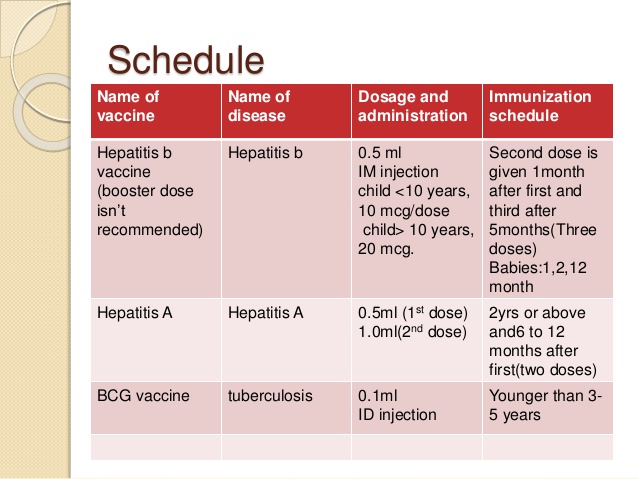

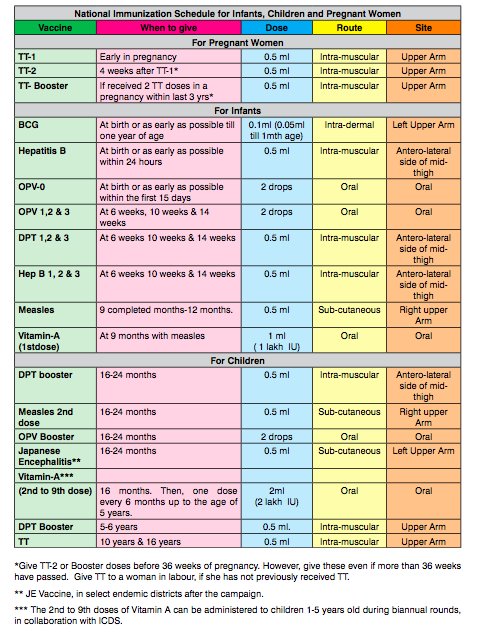

The CDC lists no precautions for breastfeeding with the following vaccines:

- Immune globulins, pooled or hyper-immune

- Diphtheria-Tetanus

- Hepatitis B

- Influenza Inactivated whole virus or subunit

- Measles

- Meningococcal meningitis

- Mumps

- Polio, inactivated

- Rubella

- Varicella[7]

We realize that many families have questions about the COVID-19 vaccine and breastfeeding. As with all medications La Leche league( LLL), and LLL Leaders cannot offer advice about vaccines. We recommend you consult your healthcare provider and any relevant Government guidance for further information, and guidance regarding your own circumstances.

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (an international organisation) has issued a statement you may find useful, read it here.

The World Health Organization have issued interim recommendations for use of the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine here.

LLL Canada have a document with resources, When Parents Ask About the COVID-19 Vaccine here.

LLLGB have this article on their website containing many useful links: Covid-19 vaccines and breastfeeding.

LLL France have questions and answers here: Allaitement et Covid-19, questions/réponses.

The European Medicines Agency have issued information you can read here.

The US based InfantRisk Center have issued this statement on COVID-19 Vaccinations.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ statement can be read here.

The International Lactation Consultant Association’s statement is here.

e-lactancia have added an entry for COVID-19 vaccinations here.

We share these for your convenience but do not endorse any source. Please keep in mind that information is being released rapidly and these may not be the most up-to-date resources.

Please keep in mind that information is being released rapidly and these may not be the most up-to-date resources.

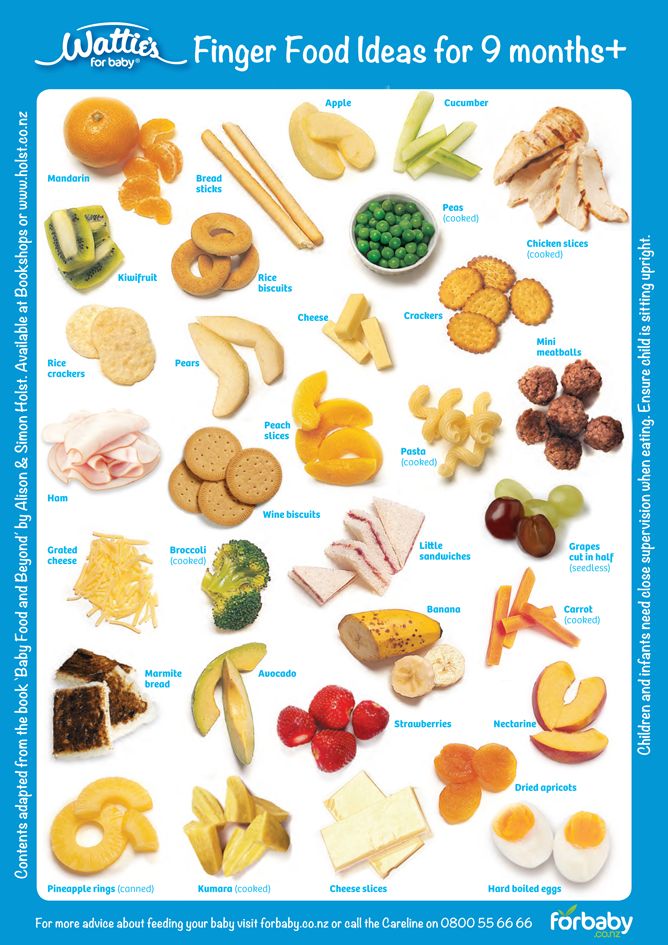

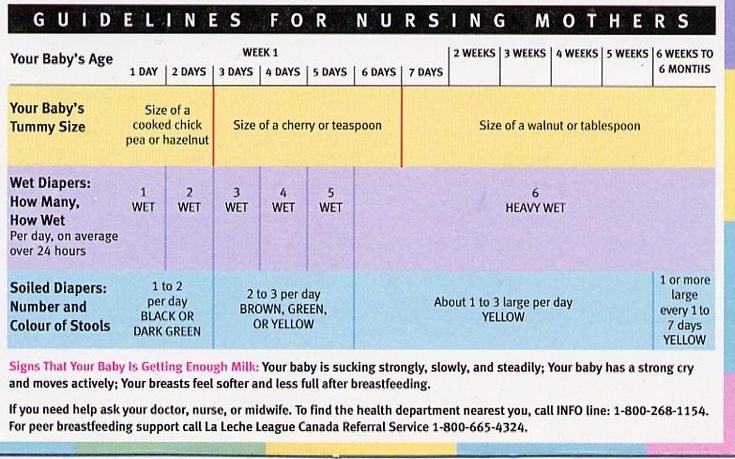

Many parents wonder about how to provide comfort for their breastfed baby receiving vaccines. For the breastfed baby, the most comforting place in the world is close to you. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the following measures for comforting infants and young children before, during, and after receiving vaccines:

- Infants and young children should be held by their caregiver

- Caregivers should be present throughout and after the vaccination procedure

- Infants should be breastfed during or shortly before the vaccination session, if it is culturally acceptable

- Distractions such as toys, videos and music are recommended for children under 6 years of age[8]

LLLI Article: Influenza

LLLI resources: breastfeeding and coronavirusLLLGB: Covid-19 vaccines and breastfeedingLLL France: Allaitement et Covid-19, questions/réponses

[1] LLLI does not offer medical advice and cannot offer an opinion as to whether or not any vaccines are appropriate in your particular circumstances. The information provided here is provided as a resource to parents wishing to discuss the information with their family health care provider(s).

The information provided here is provided as a resource to parents wishing to discuss the information with their family health care provider(s).

[2] Sachs, H.C., Committee on Drugs, The Transfer of Drugs and Therapeutics Into Human Breast Milk: An Update on Selected Topics, Pediatrics

accessed 17 December 2020

[3] https://www.infantrisk.com

[4] https://mothertobaby.org Provides information in both English and Spanish

[5] http://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/detailed-information/drugs-in-breastmilk/

[6] http://www.e-lactancia.org/,

accessed 17 December 2020

[7] https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/recommendations/vaccinations.htm, accessed 17 December 2020

[8] http://www.who.int/features/2015/vaccinations-made-friendly/en/ accessed 17 December 2020

Published January 2018, last updated March 2021.

What young mothers need to know about vaccination against COVID-19

Almost 100,000 women living on the planet are now expecting a baby, and more than 40,000 babies have been born today. All this in a world where the COVID-19 pandemic has been going on for 1.5 years. But if the expectant mother falls ill, not only her life, but also the normal development of the fetus may be in jeopardy.

All this in a world where the COVID-19 pandemic has been going on for 1.5 years. But if the expectant mother falls ill, not only her life, but also the normal development of the fetus may be in jeopardy.

Fortunately, over the past long months, doctors and scientists have collected enough information to, on the one hand, warn women, and on the other, to reliably reassure them. And new data on this sensitive issue appear literally every day. nine0003

To be vaccinated or not - that is the question. Academician V. I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia Leila Adamyan answers him unequivocally: “Yes.”

“I am close to literally persuading our ministry, our scientists and our society to vaccinate those women who are just preparing for pregnancy. If she is going to have a baby in two, three months, along with all the other vaccines, it is quite possible to afford vaccination against coronavirus infection. In our case, Sputnik V or another vaccine does not matter, ”the expert said at the IX International Congress Orgzdrav-2021, which was held from May 25 to 27 in Moscow. nine0003

nine0003

It has already been proven that immunity is passed on to the child, so vaccination becomes insurance not only for the mother, but also for the baby, said Adamyan.

However, you can get vaccinated against COVID-19 both before and during pregnancy. Observations on 100 thousand women who were vaccinated when they did not yet know that they were pregnant showed that none of the vaccines used had a negative effect.

“Vaccination has saved the world from the most serious diseases for 150 years. And now this plague of the 21st century must also be prevented with the help of this,” Adamyan is sure. nine0003

Head of the Department of Operative Gynecology, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology. Academician V. I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia Leila Adamyan

Anton Kuznetsov/TASS

Is COVID-19 dangerous for babies in the womb? If a pregnant woman falls ill, it does not affect not only the fetus, but even the placenta.

nine0003

nine0003 “We analyzed over 2,000 case histories, of which only one case was suspected of vertical transmission. The first study was questionable: it was likely that there might have been contamination during childbirth. No additional evidence was found in the same baby, ”said Adamyan.

This is a study that was carried out in the Moscow 15th city hospital named after. N. F. Filatova. The statistics included 1646 mothers who did not have coronavirus, and 891 - with COVID-19 at the time of delivery.

Newborns in the hospital underwent PCR tests immediately after birth, on days 3 and 10. And none of them tested positive for the coronavirus.

Moreover, even if the mother had a severe or moderate coronavirus infection before the birth, the children were born healthy. There is no evidence that COVID-19 causes fetal malformations.

Ekaterina Sychkov/URA.RU/TASS

Vaccination and breastfeeding

Initially, doctors forbade mothers with coronavirus from breastfeeding their babies. However, since fears of mother-to-child transmission of the virus are not confirmed, attitudes have become more loyal over time.

However, since fears of mother-to-child transmission of the virus are not confirmed, attitudes have become more loyal over time.

“We were overly careful not to allow breastfeeding. Now we want to say: due to the fact that the virus is not found in breast milk, the attitude towards this is more loyal. But, unfortunately, we cannot provide a sanitary and epidemiological regime, therefore, of course, we are worried, ”Adamyan shared. nine0003

Therefore, although breastfeeding is acceptable, mothers are still advised to take precautions.

Why then get vaccinated?

“Problems do not end with the end of treatment for the coronavirus infection itself. It is terrible in its consequences. We have amazing data that the state of the nervous system, the mental state deserves to avoid coronavirus infection by all means, ”says the expert.

Although COVID-19 does not directly threaten the child, this does not mean that it is not at all dangerous for him and for the mother. The statistics are disappointing: according to the same study conducted at the Filatov Hospital, the risk of preterm birth in pregnant women with coronavirus increases by 1.5 times. Of the more than 2,000 mothers whose births were included in the statistics, those who were not affected by covid had children born prematurely in 1.1% of cases. In women in labor with coronavirus - in 8.4% of cases. The rate of prenatal death in patients with coronavirus infection was an order of magnitude higher in women with coronavirus. nine0003

The statistics are disappointing: according to the same study conducted at the Filatov Hospital, the risk of preterm birth in pregnant women with coronavirus increases by 1.5 times. Of the more than 2,000 mothers whose births were included in the statistics, those who were not affected by covid had children born prematurely in 1.1% of cases. In women in labor with coronavirus - in 8.4% of cases. The rate of prenatal death in patients with coronavirus infection was an order of magnitude higher in women with coronavirus. nine0003

Head of the Department of Operative Gynecology, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology. Academician V. I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia Leila Adamyan

Anton Kuznetsov/TASS

“Premature babies with less body weight. And not because they are sick with a coronavirus infection! But because the state of the body is such that respiratory failure, systemic inflammatory response, thrombosis and many other points really affect the fetus, ”Adamyan explained. nine0003

nine0003

The frequency of operative delivery, caesarean sections during the pandemic in the hospital increased from 30 to 40.7%.

“Moreover, the indications for caesarean section were not obstetric. And there was a need to save women or children. That is, respiratory failure and many other points that were associated with the provision of emergency care, ”said the expert.

So, despite the positive results of studies of the effect of coronavirus on intrauterine development, pregnancy is considered one of the indications for vaccination. After all, pregnancy itself is a risk factor for complications with COVID-19.. And pregnant women who have concomitant diseases should be doubly careful.

Vaccination should be considered especially seriously by those who have metabolic disorders, diabetes, arterial hypertension or respiratory problems. These patients constitute a special risk group for complications.

Anastasia Nosova

Does breastfeeding reduce the pain of vaccination in infants aged 1 to 12 months?

nine0063 Essence

We have found that breastfeeding before and during vaccination by injection helps to reduce pain in most infants under one year of age.

Relevance

Needles are used for early vaccination of infants and for medical care during childhood illnesses. These injections are very important but painful. They cause distress to infants, and often to their parents/caregivers, and may lead to anxiety and fear of needles in the future. Breastfeeding during newborn blood tests reduces pain. Breastfeeding, when possible and feasible, can also help calm babies and reduce their pain, not only during the newborn period, but throughout infancy. nine0003

Study profile

In February 2016, we searched the medical literature for studies on the effectiveness of breastfeeding in infants aged 1 to 12 months using needles. We compared the effectiveness of breastfeeding in reducing pain (measuring crying time and using pain scales) versus keeping babies lying down with water or sugary solutions to drink. We found 10 studies with a total of 1066 children. All studies have examined whether breastfeeding reduces the pain of vaccinations. nine0003

All studies have examined whether breastfeeding reduces the pain of vaccinations. nine0003

Main results

Breastfeeding reduces crying in vaccinated babies. On average, breastfed infants cried 38 seconds less than non-breastfed infants (6 studies; 547 infants; moderate-quality evidence) and had a significantly lower pain score (5 studies; 310 infants) ; moderate-quality evidence).

No studies reported any harm (very low-quality evidence). We were unable to draw any conclusions about the risk of harm from breastfeeding healthy babies at the time of vaccination. nine0003

Looking ahead, if mothers are breastfeeding, breastfeeding can be done whenever possible to reduce pain for babies during vaccinations. More evidence is needed to know if breastfeeding helps older infants and children in the hospital while working with blood draws or performing procedures such as IVs.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence was moderate for crying time and pain scores.