Feeding tube for premature babies

Tube feeding | Bliss

Your baby may be fed using tube feeding while on the neonatal unit. Find out why this might be and information about caring for your baby while they are being tube fed.

What is tube feeding?

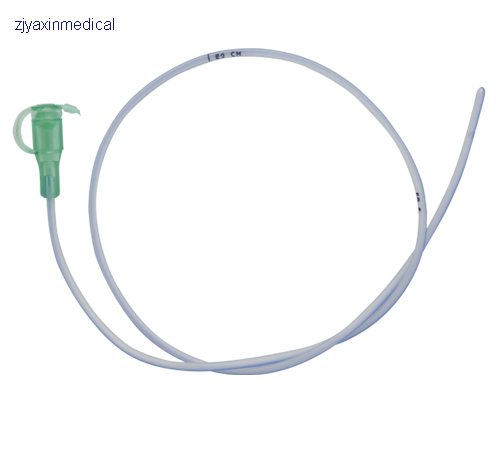

During tube feeding, breast milk or formula is given through a tube passed into your baby’s nose or mouth to their stomach. Types of tube feeding include the following:

- Nasogastric tube feeding (also called an NG tube) - This is when a baby is fed through a small soft tube, which is placed in the nose and runs down the back of the throat, through the food pipe (oesophagus) and into the stomach.

- Orogastric tube feeding - This is when a baby is fed through a small soft tube, which is placed in the mouth and runs down the back of the throat, through the food pipe (oesophagus) and into the stomach.

Babies who are very premature or sick may need to be fed using parenteral nutrition (PN) at first.

Why does my baby need to be fed using tube feeding?

Tube feeding is often used to feed premature and sick babies as they can be too small and sick to breastfeed or bottle feed at first. Babies born premature or sick have a low supply of energy and nutrients, so it is important that they are able to have small nutritional feeds often, without lowering their energy levels.

In babies born premature, the coordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing needed for effective feeding is usually not fully established until about 32 to 34 weeks’ gestation (although this is different for different babies). Babies born at term and sick may also take longer to co-ordinate feeding. Tube feeding will help your baby receive enough nutrition to grow and develop.

Can I be involved in caring for my baby if they are being tube fed?

Yes, you can. Staff on the neonatal unit will encourage you to be as involved as possible in the care of your baby on the neonatal unit. If you feel comfortable doing so, they should show you and your partner how to give tube feeds. Staff on the neonatal unit will explain how tube feeding works and will teach you how to:

If you feel comfortable doing so, they should show you and your partner how to give tube feeds. Staff on the neonatal unit will explain how tube feeding works and will teach you how to:

- Check the tube is in the correct position before feeding

- Prepare the milk and fill the syringe that is connected to the feeding tube

- Position your baby correctly for tube feeds

- Give the milk slowly to support comfortable digestion

- Know what to look for during a feed.

This can feel quite scary at first, but with practice you should gain confidence. You will have the time to give the milk very slowly which helps your baby to digest more comfortably.

If your baby is well enough to come out of the incubator, you and your partner can also practice skin-to-skin contact with your baby while they are tube feeding. Skin-to-skin contact has lots of benefits for you and your baby, and helps parents to feel closer to their baby and more confident in caring for them.

When can my baby stop tube feeding?

In time, you may notice your baby demonstrating feeding cues during a tube feed. For example, they may open and close their mouth, put out their tongue or suck their fingers during a tube feed. This shows that they might be ready to practise breastfeeding or bottle feeding.

If you are planning to breastfeed and your baby is well enough to come out of the incubator, giving them lots of opportunities to be close to the breast may help them to learn to breastfeed. During a tube feed may be a good time to do this. When they are more mature and interested enough, some babies will start licking milk and in time practice sucking. As your baby starts to take more breast and bottle feeds, they will not need as many top-ups of milk from the feeding tube. This will depend on your baby’s energy levels and their ability to coordinate sucking, swallowing and breathing.

Some parents have concerns about their baby changing from tube feeding to breastfeeding, as it is more difficult to measure how much milk their baby is having. Your baby will show signs that they are receiving enough milk, such as feeding cues and wet and dirty nappies. The healthcare team supporting you will monitor your baby’s feeding and will manage any top-ups that might be needed. Talk to a member of staff on your unit if you have any concerns.

Your baby will show signs that they are receiving enough milk, such as feeding cues and wet and dirty nappies. The healthcare team supporting you will monitor your baby’s feeding and will manage any top-ups that might be needed. Talk to a member of staff on your unit if you have any concerns.

What will happen if my baby needs to go home from the neonatal unit with a feeding tube?

If your baby is going home with a feeding tube, a member of unit staff will show you how to feed and care for the tube yourself. It may be you or your community neonatal nurse who will replace the tube when you go home. This will depend on your baby’s needs, your preferences, and the support the unit provides.

Support will always be available if you do not feel comfortable with replacing the tube yourself. If you have any questions or concerns, talk to the unit staff.

Related content

Transitioning from gavage to full oral feeds in premature infants: When should we discontinue the nasogastric tube?

Transitioning from gavage to full oral feeds in premature infants: When should we discontinue the nasogastric tube?

Download PDF

Your article has downloaded

Carousel with three slides shown at a time. Use the Previous and Next buttons to navigate three slides at a time, or the slide dot buttons at the end to jump three slides at a time.

Use the Previous and Next buttons to navigate three slides at a time, or the slide dot buttons at the end to jump three slides at a time.

Download PDF

- Article

- Published:

- Sreekanth Viswanathan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1367-91341,2 &

- Sudarshan Jadcherla1,2

Journal of Perinatology volume 39, pages 1257–1262 (2019)Cite this article

-

6830 Accesses

-

6 Citations

-

Metrics details

Subjects

- Motility disorders

- Outcomes research

Abstract

Background

The optimal timing for discontinuation of nasogastric (NG) tube in premature infants transitioning to oral feeding is not known.

Objective

To determine whether early removal of NG-tube is appropriate in low-risk premature infants.

Methods

Prospectively collected data of premature infants started on oral feeds at ≤34 weeks gestation were reviewed. Infants were categorized into ‘early’ or ‘late’ NG-removal groups based on the proportion of oral intake in the preceding 2-days, i.e., 60–79% or 80–100% of the total volume, respectively.

Results

In total 50 infants in early group vs. 43 in late group. Both groups had similar oral intake and weight change in the subsequent 2-days post-NG removal. The days from NG-removal to target oral volume, and to hospital discharge trended shorter in early vs. late group.

Conclusions

Discontinuing NG-tube when the oral feeding competency reaches ~75% of prescribed feeding volume is safe and appropriate in low-risk premature infants.

Introduction

Successful transition from full gavage to independent oral feedings is a criterion of hospital discharge in premature infants [1]. Delay in achieving full oral feeding milestone is one of the main reasons for delays in hospital discharge [2,3,4], and adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in premature infants [5]. During this period of functional immaturity of coordinating sucking, swallowing, and breathing [6], many premature infants require enteral feeding, usually by a nasogastric (NG) tube, until they achieve adequate oral feeding skills. The optimal timing for discontinuation of NG tube feeding in premature infants transitioning to oral feeding is not known, and thus associated with practice variation.

Some of the cue-based oral feeding protocols suggest to keep the NG feeding tube until the infant have appropriate weight gain for 48 hours without supplementation by NG tube [7,8,9]. However, having a NG tube is not without problems. In presence of NG tube especially with size >5F, premature infants have increased nasal airway resistance [10, 11], and reduced tidal volume and minute ventilation during sucking, which can affect their oral feeding performance [12]. Its presence can potentially increase the gastroesophageal reflux (GER) events depending on the size of NG tube [13, 14]. Use of NG tube is also associated with significant nutrient loss, especially fat, fat soluble vitamins, and minerals because fat adheres to tubing surfaces [15], and is a potential source of infection as it is easily colonized by pathogenic bacteria/fungi [16].

In presence of NG tube especially with size >5F, premature infants have increased nasal airway resistance [10, 11], and reduced tidal volume and minute ventilation during sucking, which can affect their oral feeding performance [12]. Its presence can potentially increase the gastroesophageal reflux (GER) events depending on the size of NG tube [13, 14]. Use of NG tube is also associated with significant nutrient loss, especially fat, fat soluble vitamins, and minerals because fat adheres to tubing surfaces [15], and is a potential source of infection as it is easily colonized by pathogenic bacteria/fungi [16].

If earlier removal of NG tube is safe and feasible, it can potentially reduce these complications and length of hospital stay in premature infants. Our study objective was to determine whether early removal of NG tube is safe and appropriate in relatively low-risk premature infants transitioning to oral feeding. We hypothesize that earlier removal of NG tube would lead to earlier transition to independent oral feeding resulting in decreased length of hospital stay.

Methods

The study was conducted at the all-referral level IV neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio. As part of an ongoing quality improvement (SIMPLE feeding initiatives) [17], focused on prevention and early identification of feeding related problems in premature infants, data of all infants admitted at ≤34 weeks’ post-menstrual age (PMA) were collected prospectively. NG tube sizes 6.5F or 8.0F was used for enteral feeding and feedings were typically given intermittently over 10–30min every 3 h. There was no unit guideline regarding the timing of NG tube removal during the study period from Jan 2011 to Dec 2017. In general, the decision to remove NG tube occurs when the oral feeding volume reaches 60–100% of prescribed enteral feeding depending on the individual provider comfort level.

To meet the objective of this study, SIMPLE feeding program database was reviewed for ‘low-risk’ premature infants which we defined as infants born ≤32 weeks’ gestation and had started on cue based oral feeds at ≤34 weeks’ PMA. Infants on invasive respiratory support (>2L of nasal cannula support, CPAP or ventilator support), gastrointestinal surgical conditions, intraventricular hemorrhage > grade 2, and major congenital anomalies were excluded. Among eligible infants, the day of NG tube removal was recorded and the percentage of oral feeding volume (OFV) in the preceding two days of NG tube removal was calculated from the electronic medical records. Infants were categorized into ‘early’ and ‘late’ NG removal groups. In early group, NG tube was removed when the mean OFV was between 60–79% of prescribed feeding volume in the preceding 2 days, while in late group, it occurred at 80–100%. Infants with mean OFV less than 60% in the preceding 2 days of NG removal were excluded considering their relatively quicker progression and more mature oral feeding skills. For both groups, characteristics before and at NG removal were collected from the SIMPLE feeding program database and electronic medical records. The clinical outcomes including time from NG removal to reach the target full oral feeding volume (ability to take PO of all prescribed enteral feeding volume, which generally ranges from 130 to 150 ml/kg) and to NICU discharge, and growth metrics were compared between the two groups.

Infants on invasive respiratory support (>2L of nasal cannula support, CPAP or ventilator support), gastrointestinal surgical conditions, intraventricular hemorrhage > grade 2, and major congenital anomalies were excluded. Among eligible infants, the day of NG tube removal was recorded and the percentage of oral feeding volume (OFV) in the preceding two days of NG tube removal was calculated from the electronic medical records. Infants were categorized into ‘early’ and ‘late’ NG removal groups. In early group, NG tube was removed when the mean OFV was between 60–79% of prescribed feeding volume in the preceding 2 days, while in late group, it occurred at 80–100%. Infants with mean OFV less than 60% in the preceding 2 days of NG removal were excluded considering their relatively quicker progression and more mature oral feeding skills. For both groups, characteristics before and at NG removal were collected from the SIMPLE feeding program database and electronic medical records. The clinical outcomes including time from NG removal to reach the target full oral feeding volume (ability to take PO of all prescribed enteral feeding volume, which generally ranges from 130 to 150 ml/kg) and to NICU discharge, and growth metrics were compared between the two groups. OFV in infants who are on direct breast feeding was considered as 150 ml/kg after the NG removal. The project was approved by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

OFV in infants who are on direct breast feeding was considered as 150 ml/kg after the NG removal. The project was approved by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Statistics

Appropriate bivariate analysis was performed to identify the unadjusted differences between the cases and controls. Student’s t-test was used for parametric continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for nonparametric continuous variables. Chi-square tests and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables. All quantitative data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), or median with inter-quartile range. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analysis of the data.

Results

Of the 93 eligible infants during the study period, 50 infants were in early NG removal group, the rest 43 were in late NG removal group. Early group had similar perinatal and birth characteristics, compared to the late group except that late group were exposed to more number of CPAP days (Table 1). At NG tube removal, early group had similar corrected gestational age, and body weight compared to the late group (Table 1). Early group had similar direct breast feeding rate at NG removal compared to late group (30.0 vs. 16.3%, p = 0.12). The mean OFV % in the preceding two days of NG removal was 72.3 ± 5.8 in the early group vs. 87.3 ± 4.0 in the late group (p < 0.001). The oral feeding volume and weight change in the subsequent two days after NG removal were similar in both groups (Fig. 1, Table 2). Supplemental oxygen use at initial oral feeding, at NG tube removal, at 36 weeks’ gestation, and at NICU discharge were similar in both groups. Majority of the infants reached full oral target volume before discharge (90% in early vs. 88.4 in late group, p = 0.80). Early group showed a trend for lower number of days from the NG removal to reach oral target volume (median days of 2.

Early group had similar perinatal and birth characteristics, compared to the late group except that late group were exposed to more number of CPAP days (Table 1). At NG tube removal, early group had similar corrected gestational age, and body weight compared to the late group (Table 1). Early group had similar direct breast feeding rate at NG removal compared to late group (30.0 vs. 16.3%, p = 0.12). The mean OFV % in the preceding two days of NG removal was 72.3 ± 5.8 in the early group vs. 87.3 ± 4.0 in the late group (p < 0.001). The oral feeding volume and weight change in the subsequent two days after NG removal were similar in both groups (Fig. 1, Table 2). Supplemental oxygen use at initial oral feeding, at NG tube removal, at 36 weeks’ gestation, and at NICU discharge were similar in both groups. Majority of the infants reached full oral target volume before discharge (90% in early vs. 88.4 in late group, p = 0.80). Early group showed a trend for lower number of days from the NG removal to reach oral target volume (median days of 2. 0 vs 2.5, p = 0.13, mean days 2.4 ± 1.9 vs. 4.4 ± 5.8, p = 0.051), and to NICU discharge (mean days of 10.9 vs. 13.5, p = 0.21), compared to late group. None required replacing NG tube in both groups, and none required tube feeding at discharge. The NICU discharge outcomes including BPD (oxygen requirement at 36 week PMA), length of hospital stay (LOHS), OFV, and discharge weight were similar in both groups (Table 2). A subgroup analysis of infants born ≤28 weeks and >29 weeks also did not show differences between early and late groups (Table 3).

0 vs 2.5, p = 0.13, mean days 2.4 ± 1.9 vs. 4.4 ± 5.8, p = 0.051), and to NICU discharge (mean days of 10.9 vs. 13.5, p = 0.21), compared to late group. None required replacing NG tube in both groups, and none required tube feeding at discharge. The NICU discharge outcomes including BPD (oxygen requirement at 36 week PMA), length of hospital stay (LOHS), OFV, and discharge weight were similar in both groups (Table 2). A subgroup analysis of infants born ≤28 weeks and >29 weeks also did not show differences between early and late groups (Table 3).

Full size table

Fig. 1Percentage of oral feeding volume (OFV) in early vs. late nasogastic tube removal groups

Full size image

Table 2 Outcomes after NG tube removal and at NICU discharge in early and late NG removal groupsFull size table

Table 3 Subgroup analysis stratified by GA (GA ≤ 28 vs. >29 weeks) of characteristics in the early and late NG removal groups

>29 weeks) of characteristics in the early and late NG removal groupsFull size table

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether early removal of NG tube is safe and appropriate in relatively low-risk premature infants transitioning to oral feeding. By using a prospectively collected clinical database of premature infants enrolled in the SIMPLE feeding program at our all-referral NICU, our study suggests that discontinuing NG tube when the oral feeding competency reaches ~75% of prescribed enteral feeding volume in the preceding two days is safe and appropriate in low-risk premature infants. The practice of keeping the NG tube until these infants reach their full targeted oral feeding volume is not associated with any significant clinical benefits.

In routine clinical practice, the decision to remove the NG tube is often based on the oral feeding performance of infants in the preceding days. The relationship between chronological age and functional maturity of the oral feeding skills is no t always linear, and is often influenced by growth metrics and associated co-morbidities [18]. Because of the positive association between postnatal growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes [19], potential for faltering growth with early NG tube removal is often a concern among neonatal providers. However, our data of relatively stable low-risk premature infants who have made steady oral feeding progression suggest that discontinuing NG tube when the OFV reaches about ¾ of the prescribed enteral feeding volume was not associated with significant reduction in time to achieve targeted oral feeding volume or subsequent postnatal growth until NICU discharge. Even though the late group infants were exposed to more number of CPAP days suggesting more severe early lung disease, the use of supplemental oxygen need during the oral feeding period, at 36 weeks, and at hospital discharge were similar between the two groups. Similar to our study, Fucile et al. [20], reported that setbacks in oral feeding progression are least likely to occur when the oral feeding attempt frequency reaches 6–8/day vs.

Because of the positive association between postnatal growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes [19], potential for faltering growth with early NG tube removal is often a concern among neonatal providers. However, our data of relatively stable low-risk premature infants who have made steady oral feeding progression suggest that discontinuing NG tube when the OFV reaches about ¾ of the prescribed enteral feeding volume was not associated with significant reduction in time to achieve targeted oral feeding volume or subsequent postnatal growth until NICU discharge. Even though the late group infants were exposed to more number of CPAP days suggesting more severe early lung disease, the use of supplemental oxygen need during the oral feeding period, at 36 weeks, and at hospital discharge were similar between the two groups. Similar to our study, Fucile et al. [20], reported that setbacks in oral feeding progression are least likely to occur when the oral feeding attempt frequency reaches 6–8/day vs. 1–2 or 3–5 per day. In our center, we generally consider hospital discharge, once infant is 48h off-NG tube feeding if there are no other medical or social reasons. However, infants in both our study groups were discharged from the NICU about 11–13 days after the NG tube removal. This suggests that attaining oral feeding competency is not the only reason that was delaying NICU discharge in our study population. Considering our NICU being an all-referral center, the complexity of referred infants’ initial NICU course, incidence of clinical BPD at 36 weeks PMA in about 1/3 of study infants, and other unmeasured medical and social variables may have affected the timing of NICU discharge. However, considering our specific inclusion and exclusion criteria and that all our study patients were started on oral feeding ≤34 weeks’ PMA suggest that our study cohort represents the relatively low-risk premature infants in a contemporary academic NICU hospital setting. Though the described approach and conclusions are limited to the select inclusions and exclusions of our study population, we believe, these findings may be relevant to most level-II NICUs or step-down units where the majority of such low-risk premature infants are admitted.

1–2 or 3–5 per day. In our center, we generally consider hospital discharge, once infant is 48h off-NG tube feeding if there are no other medical or social reasons. However, infants in both our study groups were discharged from the NICU about 11–13 days after the NG tube removal. This suggests that attaining oral feeding competency is not the only reason that was delaying NICU discharge in our study population. Considering our NICU being an all-referral center, the complexity of referred infants’ initial NICU course, incidence of clinical BPD at 36 weeks PMA in about 1/3 of study infants, and other unmeasured medical and social variables may have affected the timing of NICU discharge. However, considering our specific inclusion and exclusion criteria and that all our study patients were started on oral feeding ≤34 weeks’ PMA suggest that our study cohort represents the relatively low-risk premature infants in a contemporary academic NICU hospital setting. Though the described approach and conclusions are limited to the select inclusions and exclusions of our study population, we believe, these findings may be relevant to most level-II NICUs or step-down units where the majority of such low-risk premature infants are admitted.

This study was observational single-center study; consist of a heterogeneous group of relatively stable premature infants born at different gestational ages, but appropriate PMA for oral feeding initiation and maintenance. The primary outcome of the study (Days from NG removal to target full oral feeds, median days of 2.0 vs. 2.5, p = 0.13, mean days 2.4 ± 1.9 vs. 4.4 ± 5.8, p = 0.051) showed a trend for lower number of days in the early group, compared to the late group. Assuming parametric distribution of the variable, the difference between the groups has a small to medium effect size of 0.46. With this effect size, a statistically significant difference in days from NG removal to target full oral feeds between the two groups can be obtained from a sample size of 148 (74 in each group) with 80% power (α = 0.05, β = 0.20). The decision to remove NG tube was not based on a standardized unit practice, but was based on the individual provider discretion, which can be a limitation in that it adds to the subjectivity in approaches. Variability in individual views among a large number of NICU providers potentially may have influenced the study group determination and the outcomes observed. Generalization of these findings to premature infants with significant comorbidities or anomalies must be applied with caution, as our study participants did not include such patients.

Variability in individual views among a large number of NICU providers potentially may have influenced the study group determination and the outcomes observed. Generalization of these findings to premature infants with significant comorbidities or anomalies must be applied with caution, as our study participants did not include such patients.

In summary, lack of consensus regarding the timing of NG tube removal in relation to oral feeding competency in premature infants can be associated with practice variation among individual providers. Our study suggests that discontinuing NG tube when the oral feeding competency reaches ~75% of prescribed enteral feeding volume in the preceding two days is safe and appropriate in stable low-risk premature infants. Keeping NG tube longer is not associated with any additional clinical benefits. As there is no harm in discontinuing NG tube at ~75% oral feeding competency, as evidenced by similarities in growth and LOHS, at least in monitored clinical settings, this practice can be safe and may have potential benefits in lowering resource utilization, potentially reduce the length of hospitalization, increase opportunities for parent participation, all resulting in cutting down the healthcare costs.

References

Newborn AAoPCoFa. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1119–26.

Article Google Scholar

Jadcherla SR, Wang M, Vijayapal AS, Leuthner SR. Impact of prematurity and co-morbidities on feeding milestones in neonates: a retrospective study. J Perinatol. 2010;30:201–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Pickler RH, Reyna BA, Wetzel PA, Lewis M. Effect of four approaches to oral feeding progression on clinical outcomes in preterm infants. Nurs Res Pract. 2015;2015:716828.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walsh MC, Bell EF, Kandefer S, Saha S, Carlo WA, D’angio CT, et al. Neonatal outcomes of moderately preterm infants compared to extremely preterm infants.

Pedia Res. 2017;82:297–304.

Pedia Res. 2017;82:297–304.Article Google Scholar

Lainwala S, Kosyakova N, Power K, Hussain N, Moore JE, Hagadorn JI, et al. Delayed achievement of oral feedings is associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 to 26 months follow-up in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1681059. [Epub ahead of print]

Lau C, Smith EO, Schanler RJ. Coordination of suck-swallow and swallow respiration in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:721–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kirk AT, Alder SC, King JD. Cue-based oral feeding clinical pathway results in earlier attainment of full oral feeding in premature infants. J Perinatol. 2007;27:572–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kamitsuka MD, Nervik PA, Nielsen SL, Clark RH.

Incidence of nasogastric and gastrostomy tube at discharge is reduced after implementing an oral feeding protocol in premature (< 30 weeks) infants. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:606–13.

Incidence of nasogastric and gastrostomy tube at discharge is reduced after implementing an oral feeding protocol in premature (< 30 weeks) infants. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:606–13.Article Google Scholar

Davidson E, Hinton D, Ryan-Wenger N, Jadcherla S. Quality improvement study of effectiveness of cue-based feeding in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2013;42:629–40.

Article Google Scholar

Greenspan JS, Wolfson MR, Holt WJ, Shaffer TH. Neonatal gastric intubation: differential respiratory effects between nasogastric and orogastric tubes. Pedia Pulmonol. 1990;8:254–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bohnhorst B, Cech K, Peter C, Doerdelmann M. Oral versus nasal route for placing feeding tubes: no effect on hypoxemia and bradycardia in infants with apnea of prematurity.

Neonatology. 2010;98:143–9.

Neonatology. 2010;98:143–9.Article Google Scholar

Shiao SY, Youngblut JM, Anderson GC, DiFiore JM, Martin RJ. Nasogastric tube placement: effects on breathing and sucking in very-low-birth-weight infants. Nurs Res. 1995;44:82–88.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Peter CS, Wiechers C, Bohnhorst B, Silny J, Poets CF. Influence of nasogastric tubes on gastroesophageal reflux in preterm infants: a multiple intraluminal impedance study. J Pediatr. 2002;141:277–9.

Article Google Scholar

Murthy SV, Funderburk A, Abraham S, Epstein M, DiPalma J, Aghai ZH. Nasogastric feeding tubes may not contribute to gastroesophageal reflux in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35:643–7.

Article Google Scholar

Rogers SP, Hicks PD, Hamzo M, Veit LE, Abrams SA. Continuous feedings of fortified human milk lead to nutrient losses of fat, calcium and phosphorous. Nutrients. 2010;2:230–40.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Petersen SM, Greisen G, Krogfelt KA. Nasogastric feeding tubes from a neonatal department yield high concentrations of potentially pathogenic bacteria- even 1 d after insertion. Pediatr Res. 2016;80:395–400.

Article Google Scholar

Jadcherla SR, Dail J, Malkar MB, McClead R, Kelleher K, Nelin L. Impact of process optimization and quality improvement measures on neonatal feeding outcomes at an all-referral neonatal intensive care unit. JPEN J Parent Enter Nutr. 2016;40:646–55.

Article Google Scholar

Lau C. Development of infant oral feeding skills: what do we know? Am J Clin Nutr.

2016;103:616S–621S.

2016;103:616S–621S.Article CAS Google Scholar

Latal-Hajnal B, von Siebenthal K, Kovari H, Bucher HU, Largo RH. Postnatal growth in VLBW infants: significant association with neurodevelopmental outcome. J Pediatr. 2003;143:163–70.

Article Google Scholar

Fucile S, Phillips S, Bishop K, Jackson M, Yuzdepski T, Dow K. Identification of a pivotal period in the oral feeding progression of preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36:530–6.

Article Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA

Sreekanth Viswanathan & Sudarshan Jadcherla

Neonatal and Infant Feeding Disorders Research Program, Center for Perinatal Research, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

Sreekanth Viswanathan & Sudarshan Jadcherla

Authors

- Sreekanth Viswanathan

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Sudarshan Jadcherla

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sreekanth Viswanathan.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

This article is cited by

-

Oral-feeding guidelines for preterm neonates in the NICU: a scoping review

- Lise Bakker

- Bianca Jackson

- Anna Miles

Journal of Perinatology (2021)

Download PDF

Associated Content

Collection

The Importance of Nutrition: From Fetuses to Adolescents

Continuous milk feeding by nasogastric tube versus intermittent bolus milk feeding of preterm infants weighing less than 1500 g

Review question

Is continuous tube feeding through the nose or mouth better than tube feeding every two to three hours in very low birth weight preterm infants?

Relevance

Premature babies born weighing less than 1500 grams are unable to coordinate sucking, swallowing and breathing. Feeding through the gastrointestinal tract (enteral nutrition) promotes the development of the digestive system and the growth of the child. Therefore, in addition to feeding through an intravenous catheter (parenteral nutrition), premature babies can be fed milk through a tube inserted through the nose into the stomach (nasogastric feeding) or through the mouth into the stomach (orogastric feeding). Typically, a predetermined amount of milk is given over 10-20 minutes every two to three hours (intermittent bolus feeding). Some doctors prefer to feed premature babies continuously. Each feeding method has potentially beneficial effects, but can also have harmful effects.

Feeding through the gastrointestinal tract (enteral nutrition) promotes the development of the digestive system and the growth of the child. Therefore, in addition to feeding through an intravenous catheter (parenteral nutrition), premature babies can be fed milk through a tube inserted through the nose into the stomach (nasogastric feeding) or through the mouth into the stomach (orogastric feeding). Typically, a predetermined amount of milk is given over 10-20 minutes every two to three hours (intermittent bolus feeding). Some doctors prefer to feed premature babies continuously. Each feeding method has potentially beneficial effects, but can also have harmful effects.

Study profile

We included nine studies with 919 infants. Another study is pending classification. Seven of the nine included studies reported data on infants with a maximum weight of 1000 to 1400 grams. Two of the nine studies included infants weighing up to 1500 grams. The search is current as of July 17, 2020.

The search is current as of July 17, 2020.

Main results

Infants receiving continuous feeding may achieve complete enteral nutrition slightly later than infants receiving intermittent feeding. Total enteral nutrition is defined as the intake of a given volume of breast milk or formula by the infant in the required manner. This promotes the development of the gastrointestinal tract, reduces the risk of infection from intravenous catheters used to provide parenteral nutrition, and may shorten hospital stays.

It is not known whether there is a difference between continuous and intermittent feeding in terms of the number of days needed to regain birth weight, days of feeding interruption, and rate of weight gain.

Continuous feeding may result in little or no difference in rate of increase in body length or head circumference compared to intermittent feeding.

It is not known whether continuous feeding affects the risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis (a common and serious bowel disease in preterm infants) compared with intermittent feeding.

Certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence is low to very low due to the small number of children in the studies and because the studies were designed in such a way that there could be errors in the results.

Translation notes:

Translation: Alexander Mazulov. Editing: Yudina Ekaterina Viktorovna. Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia on the basis of the Russian Medical Academy of Continuing Professional Education (RMANPE). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]

Bolus Feeding Using a Syringe)

Your child is discharged from the hospital with a nasogastric (NG) feeding tube in place. The tube is a thin, soft tube that is inserted into the baby's stomach through the nose. This tube delivers liquid food directly to the stomach. Before your baby was released from the hospital, you were shown how to feed with a nasogastric tube. This memo will help you remember the necessary procedure for feeding at home. You can also get help from a district nurse at your home.

This memo will help you remember the necessary procedure for feeding at home. You can also get help from a district nurse at your home.

NOTE: There are many different types of nasogastric tubes, feeding syringes, and pumps. The appearance and function of the nasogastric tube and accessories prescribed for your child may differ from those shown and described below. Always follow the advice of your child's primary care physician or district nurse. Write down their phone numbers in case you need help. Also write down the phone number of the facility that supplies medical equipment for your child. In the future, you will need to order additional accessories that your child may need. Write down all the phone numbers you need in the spaces below.

Healthcare provider phone number: _________________________________________________________

Home health nurse phone number: _________________________________________________

Medical supply company phone number: ______________________

Types of feeding

-

Two types of feeding can be performed with a nasogastric tube:

-

bolus feeding.

Several times a day, an amount of liquid food, commensurate with one meal, is fed through the tube. Bolus feeding is done with a syringe or pump;

Several times a day, an amount of liquid food, commensurate with one meal, is fed through the tube. Bolus feeding is done with a syringe or pump; -

continuous feeding. Liquid food drips slowly through the tube. Continuous power is supplied by a pump.

-

-

Your child may be prescribed one or both types of food. Detailed instructions for each type of food are given below.

Syringe Bolus

Your child's doctor or district nurse will tell you how much liquid food to use with each bolus. You will also be told how many times a day to feed your baby. Record this information below.

How much to give at each feeding: _____________

Number of feedings per day (How often to feed): __________________________

Accessories

Actions

-

Wash your hands with soap and water.

-

Make sure the tube is in the stomach (as you were shown in the hospital). Be sure to perform this step BEFORE feeding begins.

-

Check liquid food label and expiration date. Never use jars (or bags) with food that have already expired. In this case, you must use a new jar (or bag) with food.

-

Open the hole plug at the end of the food probe.

-

Remove the plunger of the feeding syringe.

-

Connect the feeding syringe to the feeding port of the probe.

-

Gently bend or squeeze the probe with one hand. While holding the tube bent or pinched, slowly draw the liquid food into the feeding syringe with your free hand.

In this case, the food will not flow through the probe, which will allow you to measure its amount.

In this case, the food will not flow through the probe, which will allow you to measure its amount. -

Fill the feeding syringe to the level prescribed by the child's healthcare provider.

-

The probe can now be released.

-

Hold the feeding syringe straight. In this case, the food will pass through the probe by gravity without additional pressure. Adjust the angle of the feeding syringe to control the rate of fluid flow.

-

If the food flows too slowly or does not flow at all, insert the plunger into the syringe. Gently, lightly press the piston. This will remove any particles blocking or clogging the probe. Do not push the syringe plunger all the way or with force.

-

Refill the feeding syringe with food if necessary.

Repeat the above steps until the child receives the prescribed amount of food.

Repeat the above steps until the child receives the prescribed amount of food. -

After feeding, rinse the tube with water (as you were shown in the hospital).

-

Disconnect the feeding syringe.

-

Close the cap on the food inlet of the probe.

| AddiAdditional instructions:_________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Call your doctor right away if you experience any of the following.

-

The child has trouble breathing.

-

Formation of redness, swelling (swelling), leakage (leakage), ulcers (sores) or suppuration (pus) on the skin in the area of the probe.

-

Presence of blood (blood) around the probe, in the child's stool or stomach contents.

-

Baby coughing (cough), shortness of breath (choke) or vomiting (vomit) while feeding.

-

Urebenka swollen (bloated abdomen) or hard abdomen (rigid abdomen) (abdomen hard with light pressure).

-

Child diarrhea (diarrhea) or constipation (constipation).

-

Child temperature (fever) 38˚C ( 100.4° F) or higher.

© 2000-2022 The StayWell Company, LLC.