Force feeding baby solids

What to do if your baby is refusing solid food

She loves her milk or formula, but she’s not a fan of solid food. Here’s what to do.

The day after her son Ronan turned six months, Suzanne Ricard, a professor in Toronto, decided to start him on solid food. He showed all the signs of readiness: an interest in food, good head control and the ability to sit up and lean forward. He had also started picking food up from Ricard’s plate and trying to put it in his mouth.

But when Ricard offered Ronan his first spoonful of rice cereal mixed with breastmilk, he pushed it all back out with his tongue. She waited a week and then tried again—and again, he tongue-thrusted the food back out. So she experimented with different consistencies and temperatures. Oatmeal made him throw up; bananas left him blotchy; he gagged on eggs and flat out refused sweet potatoes, peas and butternut squash.

“At first we thought it was no big deal,” says Ricard. “But we soon started to worry that there was a physiological reason he couldn’t eat.” As the weeks went by, Ronan seemed hungry all the time, wanting to breastfeed every two hours. Then he began losing weight. “That’s when I started freaking out,” says Ricard. She consulted Daniel Flanders, a Toronto paediatrician who specializes in infant and child feeding, and is the owner and director of Kindercare Pediatrics.

Why babies refuse solids

Ricard had done everything right—doctors generally recommend starting solids when the baby is developmentally ready, which is usually somewhere between four and six months. And, she discovered, spitting out food is a common reflex in infants under six months. Gagging is normal and is often triggered by feeling food unexpectedly at the back of the mouth, which makes the body try to vomit. (It’s not to be confused with choking, a life-threatening condition caused when something blocks the air passage and restricts the ability to breathe. )

)

“It’s very common for babies to refuse food when solids are introduced,” Flanders says. “And it’s important to respect their decision to refuse it.” Never force your kid to eat. “Forcing sets up a power struggle around eating and can undermine the health of the feeding relationship,” Flanders says. Whether he refuses food or just seems uninterested, Flanders recommends giving your child a break of about a week before trying again. Eating, chewing and swallowing are not things babies are instantly good at, he adds—they’re learned skills.

Some doctors recommend baby-led weaning, which forgoes purées, allowing infants to control what and how much they eat.

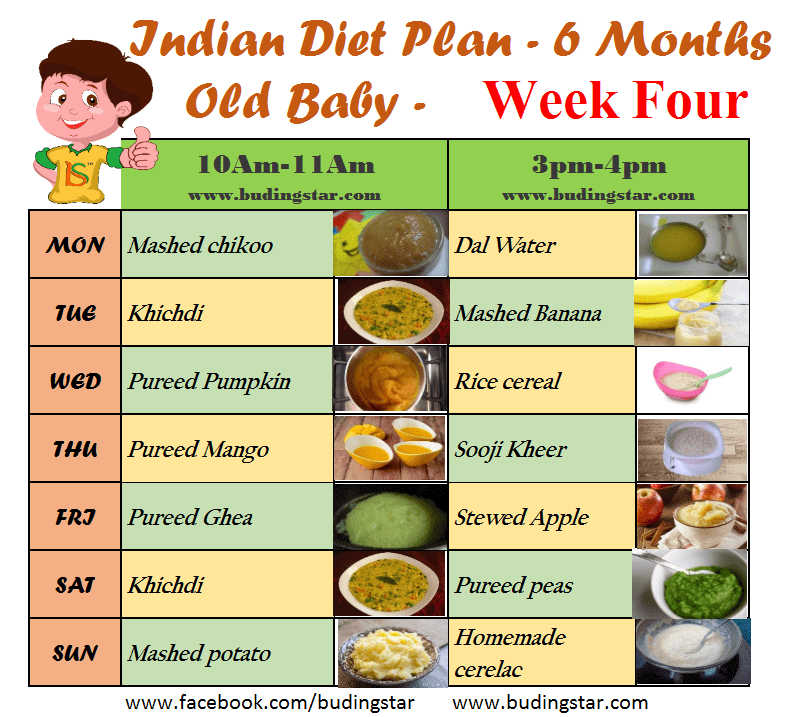

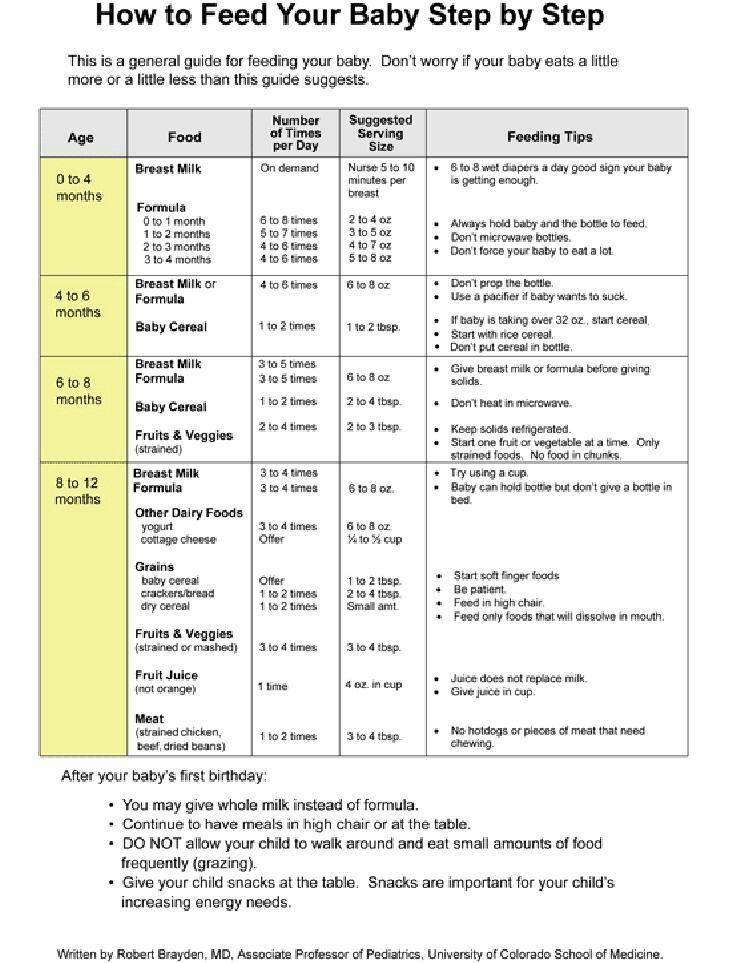

How to introduce solid food

There is no “best first food. ” A good place to start is with iron-rich foods, such as fish, meat, eggs, tofu, legumes and iron-fortified cereal, because a liquid diet of breastmilk or formula alone may not provide enough of the mineral, especially by the time a baby is six months old. Although not all doctors believe in this practice, research in the Canadian Medical Association Journal recommends introducing new foods one at a time and waiting three to five days before trying another. That way, if your baby has a sensitivity or allergy to a food, it will be a lot easier to identify the culprit.

” A good place to start is with iron-rich foods, such as fish, meat, eggs, tofu, legumes and iron-fortified cereal, because a liquid diet of breastmilk or formula alone may not provide enough of the mineral, especially by the time a baby is six months old. Although not all doctors believe in this practice, research in the Canadian Medical Association Journal recommends introducing new foods one at a time and waiting three to five days before trying another. That way, if your baby has a sensitivity or allergy to a food, it will be a lot easier to identify the culprit.

The key is perseverance, says Ali J. Chernoff, a Vancouver-based dietitian and co-author of Good Food Baby and Good Food Toddler. “You can’t determine if your baby dislikes a particular food until it has been introduced at least 15 times,” she says. It’s often a texture issue, so try to provide a variety of consistencies. Chernoff recommends items that are tender-cooked, finely minced, puréed or mashed, as well as soft finger foods, such as bite-sized pieces of soft-cooked vegetables, mushy fruits like ripe banana, deboned fish and scrambled eggs. These are more consistent with a baby-led weaning approach to starting solids. Foods should progress in texture as the baby develops his oral motor skills, and portion sizes should be small.

These are more consistent with a baby-led weaning approach to starting solids. Foods should progress in texture as the baby develops his oral motor skills, and portion sizes should be small.

When offering something new, it helps to use eye contact and verbal encouragement (not verbal or physical coercion), and to minimize distractions during meals and snacks. Don’t be tempted to put on the TV or trick your kid into taking one more bite.

If your baby is still resisting solids at seven or eight months, chat with a healthcare professional. “Between six months to a year is when kids develop eating skills, and if they’re still refusing solids, they could miss that window,” says Flanders. “It’s more challenging to teach a child who is past one year old how to eat for the very first time.”

Ronan finally started accepting solids at almost nine months, beginning with strawberries. From there, it was rice cereal, bananas, apples and mango, turkey and vegetable soup. “He didn’t begin the way most babies do,” says Ricard, “but he’s eating and gaining weight well now. ”

”

Read more:

5 tips for feeding your baby solid foods

An age-by-age guide to your baby’s eating habits

5 dos and don’ts for introducing solids to baby

Stay in touch

Subscribe to Today's Parent's daily newsletter for our best parenting news, tips, essays and recipes.- Email*

- CAPTCHA

- Consent*

Yes, I would like to receive Today's Parent's newsletter. I understand I can unsubscribe at any time.**

FILED UNDER: baby Baby 6-9 months Baby 9-12 months baby food Baby foods December 2016 Starting solids Steps and Stages

Pressure to eat | Child Feeding Guide

While pressuring a child to eat is usually done with the best of intentions, it can have unintended consequences.

Parents are often worried when their child eats very little, does not eat healthy foods like fruits and vegetables, or refuses a meal completely. For some, this worry can be significant, particularly if the child is not gaining weight well, or is losing weight. For others, uneaten meals can be a source of frustration.

For some, this worry can be significant, particularly if the child is not gaining weight well, or is losing weight. For others, uneaten meals can be a source of frustration.

Often parents find themselves using pressure, force or coercion to try and get their child to finish their meal.

This can take many forms:

- Pressure - "I want you to eat all of your carrots"

- Coaxing - "Just eat that little, tiny piece there"

- Emotional blackmail - "A good girl would eat their dinner after Mummy worked so hard cooking it"

- Use of rules - "Eat your age; three potatoes because you are three years old"

- Bribery - "If you eat everything on your plate then you can leave the table"

- Punishments - "You can't go and play outside unless you finish your spaghetti"

- Force-feeding - physically putting food into the child's mouth and forcing them to swallow

Using all of these behaviours has the opposite effect to what was intended.

While a child may eat a little more when being coerced, the act of being pressured into eating can lead to the development of negative associations with the food, and ultimately dislike and avoidance. It can also stop children from recognising and responding appropriately to internal signals of hunger and fullness, which can make them more likely to overeat in later life.

Why is it bad to pressure or strongly encourage a child to eat?

Parents' use of pressure to eat often stems from worry and anxiety regarding how or what a child is eating. Parents can become concerned about their child's health and wellbeing (and ultimate survival) if they feel that their child is not eating enough to sustain healthy development. If a child is underweight, parents are more likely to want to encourage eating and may end up using pressure without realising that they may have the opposite effect to that desired.

Parental pressure to eat can also stem from a desire to avoid wasting food that has been prepared, and the belief that children should 'clean their plates'.

However, sometimes the portion sizes that we serve to children are unrealistically large, meaning that it is unrealistic to expect the child to finish the meal and every meal will appear 'unfinished'. In this case, it is not the child eating too little, but the portion size being too large.

Pressure to eat has been linked with a number of negative consequences. These are:

- Less liking for the food

This can be caused by the negative experience of being forced to eat. Children are quick to make associations between foods and unpleasant experiences that accompany them. If a child is pressured to eat more than they wish to, then the negative emotional and/or internal feelings of being too full can become associated with a particular food, leading to a reduction in liking for the food. - Less willingness to eat the food

Similarly, willingness to try a particular food can be reduced if the initial experiences are negative. For example, a child's first exposure to cabbage may be met with refusal, either due to their natural neophobia-based response (see the food refusal pitfall section) or a lack of hunger. If this refusal was met with constant verbal coaxing and a parent attempting to put the cabbage in their mouth, the association that the child would likely make with cabbage will not be a positive one.

If this refusal was met with constant verbal coaxing and a parent attempting to put the cabbage in their mouth, the association that the child would likely make with cabbage will not be a positive one. - Overeating and overweight

Pressuring a child to eat can undermine their ability to learn appropriate appetite control. Children need to be given the opportunity to learn to recognise their body's hunger and fullness signals. Through experiencing feelings of hunger and a reduction in these feelings when they eat, children learn how their body signals that it requires more energy and, conversely, when enough energy has been consumed and it is appropriate to stop eating.

Although hunger and fullness are internal feelings, research has shown that they can be overridden by a number of factors. Pressure to eat is one way by which children might be urged to eat more than their body requires.

Over time, feelings of fullness lose their significance, as they no longer signal that the meal should stop. Rather, children learn to continue eating, even after they start to feel full, stopping only when their plate is empty, or when their parent says that it is okay to stop.

Rather, children learn to continue eating, even after they start to feel full, stopping only when their plate is empty, or when their parent says that it is okay to stop.

This means that children listen less to their body and so food intake becomes dictated by factors other than what the body requires. Research has also shown that children eat on average 30% more when offered a larger portion of food.

Offering children portion sizes that are too large and pressuring children to eat more than they desire are important factors in the development of overeating and overweight.

What should I do instead?

Except in very rare cases, children are extremely good at knowing when they are hungry and when they are full. Therefore, it is important to trust them and believe that they will eat if they are hungry. By doing this, you should not feel a need to pressure your child to eat. This is something that they will do willingly if their body requires food. Similarly, children's natural tendencies to reject new or bitter foods should not be met with pressure. Rather, keep offering foods and accept refusal, acknowledging that this is a normal developmental phase and that what you do is important in determining whether this is a positive or negative experience for your child.

Rather, keep offering foods and accept refusal, acknowledging that this is a normal developmental phase and that what you do is important in determining whether this is a positive or negative experience for your child.

Things to try

- Examine the evidence

How long is it since your child last had a snack or filling drink, such as milk? Are they really hungry? Are they too tired to sit at the table and eat well? Is your child unwell and therefore not hungry? Try using a diary to track the number and timings of snacks, drinks, meals, and naps to see if your child's routine could be contributing to their eating behaviour. - Put yourself in their shoes

Try to imagine what it would be like if you were not hungry and you were being coaxed to eat, or even force-fed, or if you were unsure of what it was you were being asked to eat. How would you feel? Empathising with your child and seeing your behaviour through their eyes will help you to recognise that this behaviour is likely to have the opposite effect than you intended. Each time your child refuses food, remember to see things from their point of view.

Each time your child refuses food, remember to see things from their point of view. - Step back and be objective

Eating should be a pleasurable experience for your child that meets a biological need. It is not about satisfying you. Try to get satisfaction from knowing that your child has eaten as much as they desire and that they feel satisfied, rather than from having them eat an amount of food that you have defined. - Trust their tummies

Our bodies are very good at letting us know when we are hungry and full. However, constant interfering - by asking children to eat when they no longer want to - can disrupt this. Eating when hungry and stopping when full is a behaviour that we want to safeguard, not undermine, so try to allow your child to tell you when they are hungry and full. - Check portion sizes. Children's tummies are smaller than adults' and you may be serving too much food and therefore setting unrealistic expectations.

As a guide, a single portion of each food is roughly what would fit in the palm of the child's hand. For example, if serving lasagne, give a palm-sized portion of the lasagne and 2-3 palm-sized portions of vegetables. For dessert, try a palm-sized portion of fruit, with a palm-sized serving of natural yogurt. Remember that all children's appetites differ, but sticking to the 'palm rule' for each food will help you avoid giving over-sized portions of single foods.

As a guide, a single portion of each food is roughly what would fit in the palm of the child's hand. For example, if serving lasagne, give a palm-sized portion of the lasagne and 2-3 palm-sized portions of vegetables. For dessert, try a palm-sized portion of fruit, with a palm-sized serving of natural yogurt. Remember that all children's appetites differ, but sticking to the 'palm rule' for each food will help you avoid giving over-sized portions of single foods.

As an example, for a two year old, a palm-sized portion of strawberries would equate to three large strawberries.

(Information about suitable portion sizes for toddlers can be found here.)

Side effects of force-feeding children

As parents, we want our children to get optimal nutrition, and for this they need to eat the right and balanced food. However, feeding your kids food can be a daunting task, especially if your child refuses to eat what you want them to eat. In such cases, parents often tend to force-feed their children, but this can lead to dire consequences. If you want to know more about why force feeding babies is bad, we suggest you skip to the next post.

If you want to know more about why force feeding babies is bad, we suggest you skip to the next post.

In this article

What does force-feeding mean?

Providing food and nutrition for a child is what every parent wants, but sometimes it is too late. force-feeds her children. The following items may constitute force feeding:

- Decide how much, when and what the baby will eat

- Feeding a child a huge amount of food, even if he is offended by it

- Compare the child to other children or blackmail the child into eating or eating a lot of food.

- Ignore child's requests to eat less or later

Why do parents usually force feed their children?

As parents, we do our best to ensure that our children are properly raised, feeding and providing food is one of them. Here are a few reasons why parents tend to force feed their babies:

1. To finish what's on his plate

Most of us think that once it's on the plate, it must end up in our stomach. But with babies it is different, because they will only eat as much as their stomach allows.

But with babies it is different, because they will only eat as much as their stomach allows.

2. When serving solid food

This is a very common feeding mistake that parents make when they first start feeding their babies. The goal is not to force the child to eat food he despises, but to let the child develop a taste and then let him choose what he likes to eat.

3. Worry about the child not eating enough.

Babies Eat Less, Eat More As parents, we think that our child may not be eating or getting enough small amounts of food, which leads to overfeeding.

4. Feeding spoon for older children.

Some parents like to feed their children even when they are old enough to eat themselves, because they think they cannot feed themselves. This leads to overfeeding.

5. Misunderstanding of the child's needs.

As parents, we think we are more aware of what our child needs, and the same goes for food. Therefore, when a child refuses to eat, we often tend to force feed, thinking that the child does not understand the demands of his body.

6. Introducing new foods

Parents often force their children to eat when they are introduced to a new fruit, vegetable, or food. This opinion supports the idea that infants need to be constantly given food so that they can sort out the taste.

7. Compare with other children.

If a friend or cousin of a child of the same age eats more food, parents may feel that they are not good at feeding the child and that they prefer force feeding.

8. Inculcate good habits.

The fact that a certain food is good for health does not mean that you force the child to eat it. Parents often think that in order to instill good eating habits in their children, they need to teach them to eat certain foods, even if they don't like them.

What are the consequences of force feeding?

We understand that as parents you do your best to raise your child and food is an integral part of it. However, force-feeding should be avoided.

Here are some of the effects force-feeding can have:

1.

When you feed your baby against his will, he may vomit or vomit.

2. Aversion to food

A child can not only hate that you can feed him, but also make him resist this food.

3. Loss of appetite.

We eat when we are hungry, and so do the children. But as parents, we question our children's judgments about food, and therefore force-feeding. It kills their appetite.

4. Negative emotions.

The child may develop negative feelings and emotions towards food and even towards the parent.

5. This leads to unhealthy eating.

Your child may develop unhealthy eating habits because he may develop a hatred of healthy foods.

6. Lack of control over eating habits.

One of the worst side effects of forcing babies or older children is that they can lose control of themselves. Their eating habits.

7. Eating disorders

Eating disorders such as anorexia, bulimia, etc. may develop due to lack of control over food intake

8.

Eat less than there is more.

Eat less than there is more.

9. He hates food all his life.

Babies can get very upset and hate food as they get older.

10. Parental control over food leads to nutritional problems.

When parents force feed their children, they may end up feeling lost and out of control of their lives. This can lead to problems with low self-esteem.

How to stop forcing children to eat?

Forced feeding of children. Young or older children can cause many physical, emotional and physiological problems. So it's important to understand why you're force-feeding your baby and look for the trigger that might be causing this behavior.

If you feel that your child eats less than his brother, or refuses to eat, is more immersed in play than food, etc., then this is quite normal. You must remain calm and not panic, let your child come and ask for it.

What you can do to get your child to eat properly without forcing him

Here's what you can do:

- Eating with your son

- Be patient when introducing something new

- If the child is distracted, return his attention

- be patient

questions and answers

Here are some common questions that can be answered in your favor:

1.

Should you force your child to eat if he is picky?

Should you force your child to eat if he is picky? If your child is picky, the first thing you need to determine is the root cause. This will help you better deal with the situation. Even if your child is overloaded and skips meals, it's best to leave him alone and come back to you when he's hungry.

2. How can I instill good eating habits in my child?

In addition to being a good role model, letting your child determine meal times, preferences, and other such factors can help undermine good eating habits.

It is important to feed the child with healthy food, but not at the expense of feeding him with the Force. Talk to your doctor if your child has difficulty eating.

Helping children develop healthy eating habits

Maureen M. Black, PhD, Kristen M. Hurley, PhD

University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA

, 2nd rev. ed. (English language). Translation: August 2015

ed. (English language). Translation: August 2015

Introduction

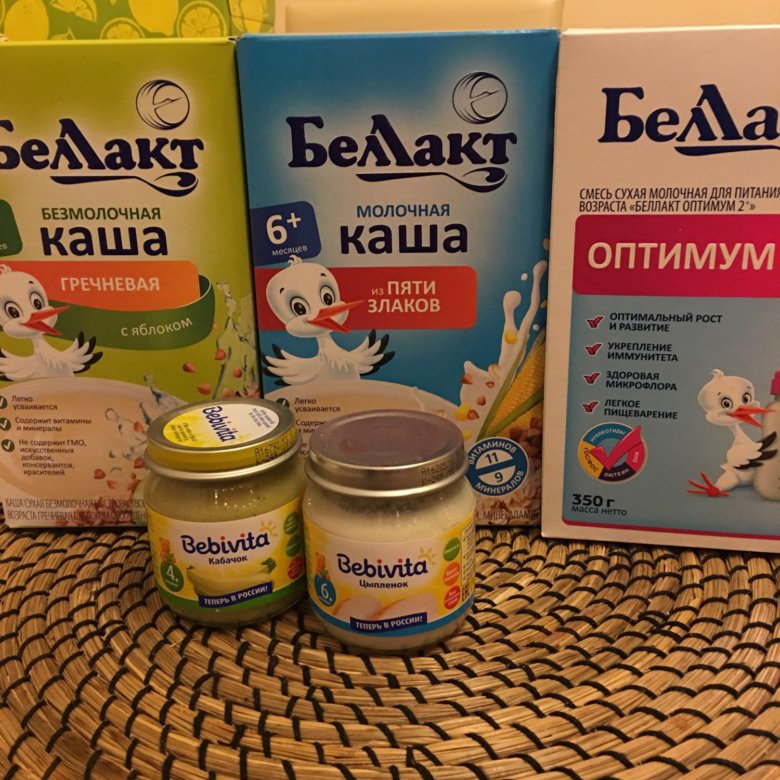

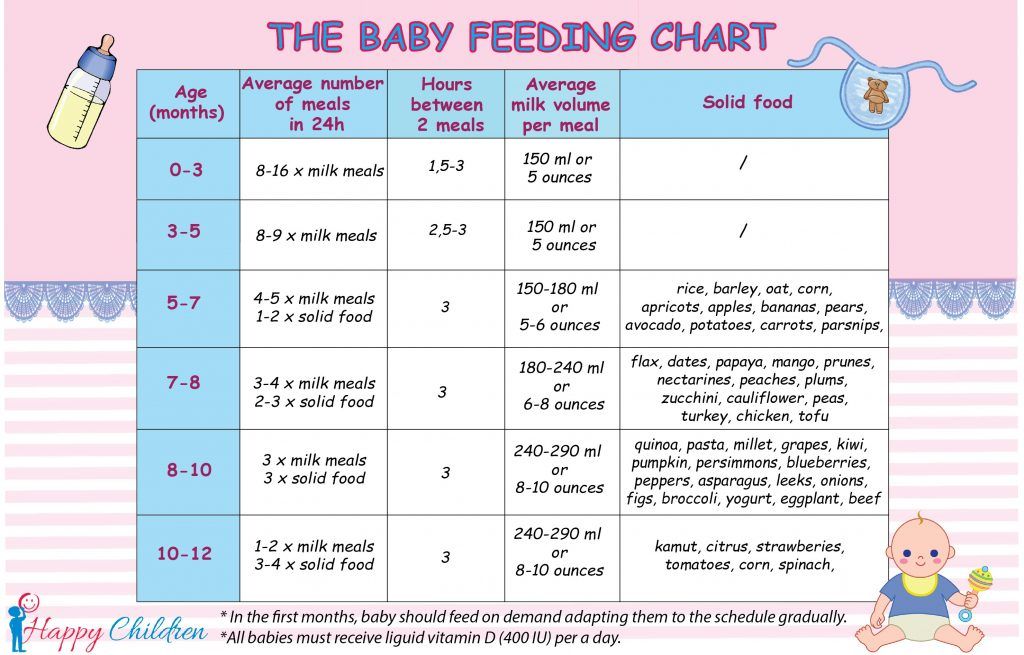

The first year of a child's life is characterized by rapid age-related changes related to nutrition. As infants gain control of their own bodies, they move from the stage of sucking liquids in a recumbent or reclining position to the stage of eating solid foods in a sitting position. Oral motor skills are developed, moving from a basic "sucking-swallowing" mechanism based on breast milk or formula to a "chewing-swallowing" mechanism based on the consumption of semi-solid foods, gradually moving to more complex combined types of food. 1.2 When babies are already well regulated in their movements, they move from passive feeding, in which someone feeds them, to independent feeding, at least occasionally. The infant's diet is enriched: through the introduction of mashed potatoes and specially prepared foods, the transition is made from breast milk and formula for feeding to the family diet. By the end of the first year of life, children are already able to sit, chew and swallow on their own, consuming different types of food, learn to eat independently and move on to a diet and diet that is characteristic of the whole family.

By the end of the first year of life, children are already able to sit, chew and swallow on their own, consuming different types of food, learn to eat independently and move on to a diet and diet that is characteristic of the whole family.

As children make the transition to a family diet, the advice is not only about food, but also about nutrition. A variety of healthy foods improves the quality of the diet in the same way as early and regular recognition of new types of food by the child. Data on infants and young children aged 6 to 23 months, collected in 11 countries around the world, show a positive relationship between dietary diversity and nutritional status (nutritive status). 3 Teaching a child to consume fruits and vegetables during infancy and early childhood is associated with the adoption of these types of food at an older age. 4-6

Eating habits and preferences are formed in children at an early age. If children forgo nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables, mealtimes can become stressful or wrestling. As a result, children may be deprived of both the nutrients they need and healthy, understanding relationships between them and caregivers. Adults who are inexperienced or stressed, and those who themselves have unhealthy eating habits, need help to establish healthy and fulfilling eating behaviors in children during the meal.

As a result, children may be deprived of both the nutrients they need and healthy, understanding relationships between them and caregivers. Adults who are inexperienced or stressed, and those who themselves have unhealthy eating habits, need help to establish healthy and fulfilling eating behaviors in children during the meal.

Subject

Eating problems occur in 25% - 45% of all children, especially during the period when children learn new skills, and new types of food or expectations associated with eating them become real for them test. 7 For example, the period of infancy and early childhood is characterized by a desire for independence - children try to do everything on their own. When these characteristics are also applied to eating behavior, it suggests that children may be neophobic (fear of trying new foods) and insist on a limited set of foods consumed, 8 which further leads to the perception of these children as picky eaters.

Most eating problems are temporary and easily resolved with little or no intervention. However, when such problems continue for a long time, their presence can slow down the child's growth, development and worsen relationships with people caring for him. This leads to long-term problems with the health and development of the child. 9 Children with persistent eating problems may be at risk of developing growth and behavioral problems if caregivers do not seek help in a timely manner, allowing a critical situation to develop.

Issues

Eating habits are influenced by age, family or environment. As they mature and are able to make the transition to a family diet, their internal regulatory signals for hunger and satiety may be suppressed by family and cultural patterns. In families where adults lead by example in healthy eating, children are more likely to eat more fruits and vegetables than children in families where they do not. At the same time, in a family where it is customary to eat less healthy food, snacks are abused, children are likely to have eating habits and taste preferences characterized by the consumption of excess amounts of fat and sugar. 10 In terms of environmental influences, children's exposure to fast food restaurants and similar establishments has resulted in an increased intake of high-fat foods such as french fries, while not eating more nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables. 11 What's more, adults may not realize that many commercial products advertised as products for children (such as sugary drinks) can satisfy hunger or thirst but provide minimal nutritional intake. 12

10 In terms of environmental influences, children's exposure to fast food restaurants and similar establishments has resulted in an increased intake of high-fat foods such as french fries, while not eating more nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables. 11 What's more, adults may not realize that many commercial products advertised as products for children (such as sugary drinks) can satisfy hunger or thirst but provide minimal nutritional intake. 12

A number of nationwide studies have documented excessive consumption of high-calorie foods during early childhood, 13.14 while many children consume critically low amounts of fruits, vegetables and essential micronutrients. 15 By the time they enter primary school, many children get half their fluid intake from sugary drinks. 16 This eating habit is undoubtedly developed during early childhood and preschool age. The presence of these unhealthy eating habits (eating foods high in fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates; sugary drinks; eating limited fruits and vegetables) increases the likelihood of micronutrient deficiencies (such as iron deficiency anemia) and overweight in young children. 17

17

Scientific context

The process of eating is often studied through observational data or adult reports of eating behavior. Some investigators rely on clinical study of groups of children with stunting or nutritional problems, others select children without any abnormalities for research.

Key questions

Key questions are about the development of eating habits from infancy through early childhood, and the methods by which children report feeling hungry or full. In addition, this includes studying the reasons why some children (so-called "picky eaters") have selective food preferences. Key challenges for caregivers and families are to find ways to promote healthy eating habits in young children, encourage children to eat healthy foods, and prevent problems with feeding and growth.

Recent Research Findings

Attachment and Nutrition

Healthy eating habits are developed in infancy as infants and their parents develop a partnership in which they recognize and interpret both verbal and non-verbal communication cues each other.![]() This reciprocal process forms the basis for building an emotional bond or attachment in infants and caregivers that is an integral part of healthy social functioning. 18 If communication between a child and adults is disrupted, characterized by incoherent, unresponsive interactions, then bonds of attachment can be unreliable, resulting in the process of eating can turn into unproductive, exhausting quarrels over food.

This reciprocal process forms the basis for building an emotional bond or attachment in infants and caregivers that is an integral part of healthy social functioning. 18 If communication between a child and adults is disrupted, characterized by incoherent, unresponsive interactions, then bonds of attachment can be unreliable, resulting in the process of eating can turn into unproductive, exhausting quarrels over food.

Infants who do not communicate clearly about their needs, or who do not respond to caregivers' attempts to teach them regular and predictable habits related to eating, sleeping, and playing, are at risk of developing regulatory problems associated with eating as well. 9 Premature or sick babies may react more slowly than full-term babies, making it more difficult for these babies to express feelings of hunger or fullness. Adults who do not recognize signs of satiety in their children tend to overfeed them, causing infants to associate satiety with frustration and conflict.

Feeding in the context of the adult-child relationship

Variability in the context of the adult-child relationship during feeding is associated with feeding behavior and growth of the child. 19 Aspects of parental behavior and guardianship, which include factors of perception and understanding of the child's behavior, are also applicable to the nature of feeding (Table 1). 20,21,22 Responsive feeding reflects an interaction-based behavior pattern in which adults provide control and developmentally appropriate responses to a child's hunger or satiety signals. The unresponsive feeding process is marked by a lack of reciprocity between adults and the child. This is characterized by parents being overly in control of the feeding process (by forcing the child to eat or limiting the child's diet), or by the fact that the child controls the feeding process (for example, requires a limited menu, or eats only after much persuasion), or by the fact that an adult ignores the child's signals, or cannot organize the correct diet (isolated feeding). 23.24

23.24

parents and child are in a relationship where requirements are clearly expressed and there is a mutual interpretation of signals for feeding. Responsive feeding is characterized by short-term interaction based on behavioral characteristics and consistent with a certain stage of development of the child. In the course of this interaction, both sides easily compromise. 22,25,26

A controlling feeding style, well structured but low in caring, is typical of parents who use forceful or restrictive strategies to control eating. A controlling feeding style is part of an authoritarian parenting model and may include overly assertive behaviors such as loud talking, force feeding, or other ways to get a child to do what they want. 27 Parents who control the feeding process can suppress the child's internal regulatory signals of hunger or satiety. 28 Infants' innate ability to self-regulate energy consumption disappears during early childhood due to the influence of family and cultural patterns.![]() 29

29

An indulgent feeding style, characterized by a high level of caring and less structure, is an element of the indulgent parenting model. With this style of feeding, parents allow the child to decide for himself what to eat and when. 23 If the parents do not refer the child, the child is more likely to choose foods high in salt and sugar over a more balanced diet that includes vegetables. 23 Thus, an indulgent feeding style can be problematic given the genetic predisposition of infants to salty or sugary foods. 30 Babies whose parents practice indulgent feeding styles often weigh more than children of parents who use other feeding styles. 24

Detached feeding style, characterized by both low levels of nurturance and a less structured structure, is characteristic of parents with a lack of knowledge and participation in their child's eating behavior. 23 A detached feeding style may show signs such as lack of active assistance or verbalization during feeding, lack of rapport between parent and child, negative feeding environment, and lack of an orderly structure or defined feeding pattern. Indifferent parents often ignore both the feeding advice and the child's signals of hunger or satiety; they may not know what and when their child eats. Egeland and Sroufe 31 found that children of distant or psychologically unavailable parents were more likely to experience anxiety compared to children whose parents were actively involved in the process. Accordingly, a detached feeding style is an element of a detached parenting style. 23

Indifferent parents often ignore both the feeding advice and the child's signals of hunger or satiety; they may not know what and when their child eats. Egeland and Sroufe 31 found that children of distant or psychologically unavailable parents were more likely to experience anxiety compared to children whose parents were actively involved in the process. Accordingly, a detached feeding style is an element of a detached parenting style. 23

Several recent systematic reviews have shown an association between parental control of feeding and infant and young child weight gain and/or weight class. 24,32,33 Control feeding is associated with weight gain (eg, children whose parents have a restrictive feeding style tend to overeat) 34 and weight loss (eg, children who are forced to eat more do not tend to overeat). 35 However, the cross-sectional nature of most studies, coupled with a tendency to rely exclusively on parental behavioral data without considering the importance of interactions during feeding, makes it difficult to understand parent-child interactions during feeding. A recent double-blind study of infants in Australia found that adherence to preventive infant feeding guidelines led to normal weight gain and improved mutual understanding during feeding, as judged by the respondents. 36 More research is needed to better understand strategies for promoting healthy relationships that are important for a child's feeding and healthy growth.

A recent double-blind study of infants in Australia found that adherence to preventive infant feeding guidelines led to normal weight gain and improved mutual understanding during feeding, as judged by the respondents. 36 More research is needed to better understand strategies for promoting healthy relationships that are important for a child's feeding and healthy growth.

Food preferences

Children who grow up in families where parents set an example of healthy eating behavior (for example, eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables) develop similar food preferences. 4

Food preferences are also influenced by accompanying conditions. Children are more likely to avoid foods associated with unpleasant physical symptoms, such as nausea or pain. They may also avoid eating food associated with anxiety or distress caused by feeding disputes and confrontations.

Children also choose food based on qualities such as taste, texture, smell, temperature, or appearance, as well as environmental factors such as setting, presence of others, and perceived consequences of eating or not eating.![]() For example, consequences of eating may include satiety, participation in a social function, or parental attention. Consequences of not eating can include things like extra play time, being the center of attention, or snacking instead of a normal meal.

For example, consequences of eating may include satiety, participation in a social function, or parental attention. Consequences of not eating can include things like extra play time, being the center of attention, or snacking instead of a normal meal.

The degree of familiarity with the taste of food increases the likelihood that the child will accept it. 37.38 Parents can make it easier to introduce new foods to their diet by regularly pairing them with familiar foods until the baby becomes familiar with the food.

Conclusions

Eating habits are formed early in development as a response to internal regulatory cues, parent-child relationships, dietary patterns, food offerings, and family behavior patterns. Teaching children to eat fruits and vegetables early in their development develops a lifelong preference for these foods. It is necessary to conduct research on the factors that determine the context of the relationship between an adult and a child in a feeding situation, at an individual level, in an interaction situation and at the level of the external environment. The relationship between responsive/non-responsive feeding styles and children's feeding behavior in relation to weight gain should also be explored, and population-specific tools to measure responsive/non-responsive feeding characteristics should be developed. 24

The relationship between responsive/non-responsive feeding styles and children's feeding behavior in relation to weight gain should also be explored, and population-specific tools to measure responsive/non-responsive feeding characteristics should be developed. 24

Eating behavior during early childhood largely depends on parents and is developed through the acquisition of experience with food and its use. A system of education and support involving health professionals (i.e. health visitors, family doctors and pediatricians) and nutrition programs should be established so that parents always have the opportunity to seek help with their child's eating behavior.

Parents should combine their own meals with the feeding of the child in order to instill similar eating habits in him, and also to make the process of eating a pleasant experience for the child. Eating together allows children to watch their parents try new foods and helps them express feelings of hunger and satiety, as well as enjoyment of certain foods. 39

39

Parents control both the choice of food and the creation of a certain atmosphere in the process of feeding. Their "job" is to provide children with healthy food at fixed times and in pleasant surroundings. 39 By developing a certain diet, parents help children learn to consciously wait for the next meal. Children acquire the knowledge that the feeling of hunger will soon pass, and that they have no reason to be anxious or irritated. Children should not snack or eat throughout the day - this develops a sense of anticipation of a meal and the appearance of an appetite at a certain time. 39

Meals should be a pleasant family event, when all family members eat together and discuss the events of the day. When the duration of meals is shortened (less than 10 minutes), children may not have enough time to eat, especially during the period when they are learning to eat on their own, and the process of eating slows down. At the same time, it is difficult for a child to eat food that lasts more than 20 or 30 minutes, so such food can cause a feeling of disgust.

When feeding is accompanied by distractions such as watching TV, family disputes, or other extraneous activities, it can be difficult for children to focus on food. Parents should separate meal times from play activities and avoid using toys, playing games, and not watching TV - all of these factors can distract the child from eating. Special equipment for children – high chairs, bibs and small utensils – encourages feeding and enables children to develop self-feeding skills.

Advice

Advice may be about the environment, family or individual. In the environment, having healthy and tasty menus for young children at fast food restaurants can help avoid many of the problems associated with regularly eating high-fat foods (like french fries) instead of more nutritious foods like fruits and vegetables. Infant feeding recommendations should include the following information: information about the child's nutritional needs, methods to encourage healthy eating behaviors (including learning to recognize hunger or satiety signals and developing a specific type of interaction between parents and child during feeding), information on choosing the right time for about feeding, about ensuring regular feeding hours, about introducing new food into the diet through its modeling, data on ways to neutralize stressful and conflict situations during feeding. In terms of individual counseling, programs that help children develop healthy eating habits through nutrient-rich foods and develop the habit of eating to satisfy hunger rather than emotional needs can help prevent potential health and developmental problems. 40

In terms of individual counseling, programs that help children develop healthy eating habits through nutrient-rich foods and develop the habit of eating to satisfy hunger rather than emotional needs can help prevent potential health and developmental problems. 40

Literature

- Bosma J. Development and impairments of feeding in infancy and childhood. In: Groher M.E., ed. Dysphagia: Diagnosis and management . 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997:131-138.

- Morris SE. Development of oral motor skills in the neurologically impaired child receiving non-oral feedings Dysphagia 1989;3:135-154.

- Arimond M, Ruel MT. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: Evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. The Journal of Nutrition 2004;134:2579-2585.

- Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, Ziegler P, Reidy K. Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predictary dietary variety in school-aged children? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2002;34(6):310-315.

- Schwartz C, Scholtens PA, Lalanne A, Weenen H, Nicklaus S. Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite . 2011;57(3):796-807.

- Mennella JA, Nicklaus S, Jagolino AL, Yourshaw LM. Variety is the spice of life: strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable acceptance during infancy. Physiol Behav . 2008;22;94(1):29-38.

- Linscheid TR, Budd KS, Rasnake LK. Pediatric feeding disorders. In: Roberts MC, ed. Handbook of pediatric psychology . New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:481-498.

- Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L. What kind of exposure reduces children's food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. Appetite 1987;9(3):171-178.

- Keren M, Feldman R, Tyano S. Diagnoses and interactive patterns of infants referred to a community-based infant mental health clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2001;40(1):27-35.

- Palfreyman Z, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Development of the Parental Modeling of Eating Behaviours Scale (PARM): links with food intake among children and their mothers. Maternal and Child Nutrition . 2012 [Epub ahead of print].

- Zoumas-Morse C, Rock CL, Sobo EJ, Neuhouser ML. Children's patterns of macronutrient and intake associations with restaurant and home eating. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2001;101(8):923-925.

- Smith MM, Lifshitz F. Excess fruit juice consumption as a contributing factor in nonorganic failure to thrive. Pediatrics 1994;93(3):438-443.

- Ponza M, Devaney B, Ziegler P, Reidy K, Squatrito C. Nutrient intakes and food choices of infants and toddlers participating in WIC. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):71-79.

- Devaney B, Kalb L, Briefel R, Zavitsky-Novak T, Clusen N, Ziegler P. Feeding infants and toddlers study: overview of the study design.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):8-13.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):8-13. - Picciano MF, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL, Mitchell DC, Murray-Kolb L, McConahy KL. Nutritional guidance is needed during the dietary transition in early childhood. Pediatrics 2000;106(1):109-114.

- Cullen KW, Ash DM, Warneke C, de Moor C. Intake of soft drinks, fruit-flavored beverages, and fruits and vegetables by children in grades 4 through 6. American Journal of Public Health 2002;92(9): 1475-1477.

- Brotanek JM, Gosz J, Weitzman M, Flores G. Secular trends in the prevalence of iron deficiency among US toddlers, 1976-2002. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2008;162:374-81.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . New York: Psychology Press, 1978.

- Rhee K. Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning.

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2008;615:11–37.

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2008;615:11–37. - Baumrind D. Rearing competent children In: Damon W, ed. Child development today and tomorrow. San-Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1989:349-378.

- Maccoby EE, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, ed. Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development. Vol 4 . New York, NY: John Wiley; 1983:1-101.

- Black MM & Aboud FE. Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. Journal of Nutrition 2011;141(3):490-4.

- Hughes SO, Power TG, Fisher JO, Mueller S, Nicklas TA. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 2005;44(1):83-92.

- Hurley KM, Cross MB, Hughes SO. A systematic review of responsive feeding and child obesity in high-income countries.

Journal of Nutrition 2011;141:495-501.

Journal of Nutrition 2011;141:495-501. - Leyendecker B, Lamb ME, Scholmerich A, Fricke DM. Context as moderators of observed interactions: A study of Costa Rican mothers and infants from differing socioeconomic backgrounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development 1997;21(1):15-24.

- Kivijarvi M, Voeten MJM, Niemela P, Raiha H, Lertola K, Piha J. Maternal sensitivity behavior and infant behavior in early interaction. Infant Mental Health Journal 2001;22(6):627-640.

- Beebe B, Lachman F. Infant research and adult treatment: Co-constructing interactions . Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press; 2002.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO. Mothers' child-feeding practices influence daughters' eating and weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000;71(5):1054-1061

- Birch LL, Johnson SL, Andresen G, Peters JC, Schulte MC. The variability of young children's energy intake. New England Journal of Medicine 1991;324(4):232-235.

- Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition 1999;19:41-62.

- Egeland B, Sroufe LA. attachment and early maltreatment. Child Development 1981;52(1):44-52.

- DiSantis KI, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Fisher JO. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: a systematic review. International Journal of Obesity 2011;35:480-92.

- Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obesity Research 2004;12(11):1711-1722.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003;78(2):215-220.

- Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Parental influences on young girls' fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes.