Nestle baby food south africa

Nestle's Infant Formula Scandal

Nestle's Infant Formula Scandal Search iconA magnifying glass. It indicates, "Click to perform a search". Insider logoThe word "Insider".US Markets Loading... H M S In the news

Chevron iconIt indicates an expandable section or menu, or sometimes previous / next navigation options.HOMEPAGEFinance

Save Article IconA bookmarkShare iconAn curved arrow pointing right. Read in app Baby Milk Action pdf inspired us to look into the dubious history of this product.

Outrage started in the 1970s, when Nestle was accused of getting third world mothers hooked on formula, which is less healthy and more expensive than breast milk.

The allegations led to hearings in the Senate and the World Health Organization, resulting in a new set of marketing rules.

Yet infant formula remains a $11.5-billion-and-growing market.

'The Baby Killer' blew the lid off the formula industry in 1974.

Baby Milk Action pdfSocial rights groups began dragging the industry's exploitative practices into the spotlight in the early 1970s.

The New Internationalist published an exposé on Nestlé's marketing practices in 1973, "Babies Mean Business," which described how the company got Third World mothers hooked on baby formula.

But it was "The Baby Killer," a booklet published by London's War On Want organization in 1974, that really blew the lid off the baby formula industry.

Nestlé was accused of getting Third World mothers hooked on formula

YouTube / All About IBFANNevermind that these women lived in squalor and struggling to survive.

In poverty-stricken cities in Asia, Africa and Latin America, "babies are dying because their mothers bottle feed them with Western-style infant milk," alleged War on Want.

Nestlé accomplished this in three ways, said New Internationalist:

- Creating a need where none existed.

- Convincing consumers the products were indispensable.

- Linking products with the most desirable and unattainable concepts—then giving a sample.

Meanwhile, research was proving breastfeeding was healthier.

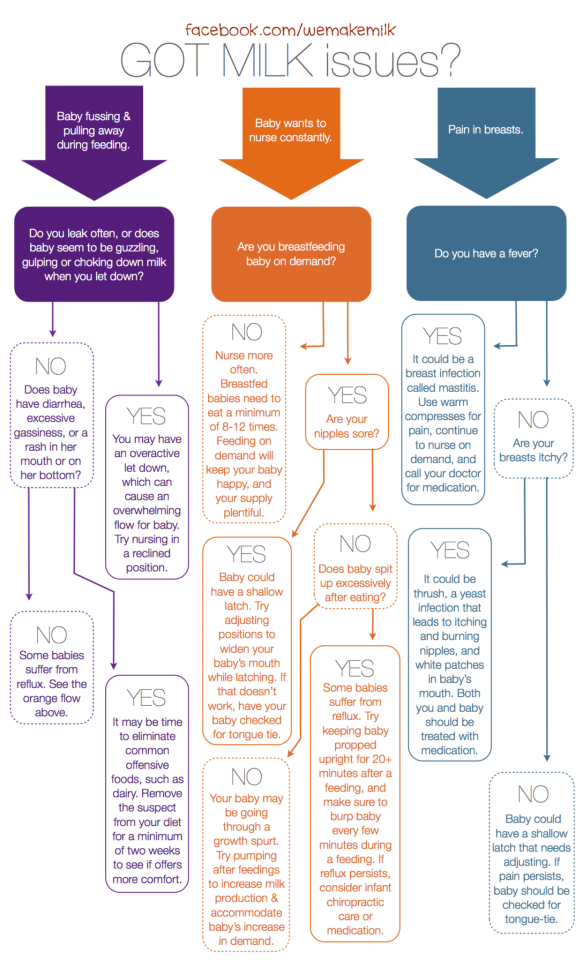

Flickr"At the same time, the benefits of breastfeeding were being brought to light," Paige Harrigan a senior nutrition advisor with Save the Children, told Business Insider.

Vitamin A prevents blindness and lowers a child's risk of death from common diseases, while zinc might stave off diarrhea, according to the organization's State of the World Report. Six months of exclusive breastfeeding are said to increase a child's chance of survival by six times.

Still, third world women yearned for Westernization.

Flickr / x-ray delta onePoor women longed to move from a rural to an urban way of life, which prodded them to abandon breastfeeding and in turn primed them for marketing, said War on Want:

"As the social position of women changes and they go out to earn a wage . .. looking at the breast as a cosmetic sex symbol rather than a source of nourishment reinforces the trend."

.. looking at the breast as a cosmetic sex symbol rather than a source of nourishment reinforces the trend."

War on Want said this undermined women's confidence in breastfeeding.

YouTube / All About IBFANPlaying into undernourished women's fear of harming their newborn was a "confidence trick," said War on Want. When these women felt fear, pain or sadness, their milk would dry up as a result.

The "letdown reflex, which controls the flow of milk to the mother's nipple is a nervous mechanism," the paper said. "Somehow mothers are deciding that a bottle is necessary to the milk she provides ... some mothers may even become so concerned about not having enough milk that they will not have enough."

"Somehow mothers are deciding that a bottle is necessary to the milk she provides ... some mothers may even become so concerned about not having enough milk that they will not have enough."

Hospitals were also accused of pushing mothers to use formula.

YouTube / All About IBFANThis worked on two levels, said New Internationalist: In exchange for handing out "discharge packs" of formula, hospitals received freebies like formula and baby bottles.

"The most insidious of these is a free architectural service to hospitals which are building or renovating facilities for newborn care," the authors wrote.

Beyond that, the authors said "baby milk companies spend untold millions of dollars subsidizing office furnishings, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications and travel junkets of the medical profession."

Meanwhile in the Third World, women tried to save money by diluting the formula.

YouTube / All About IBFANFormulas had to be mixed with water, but Third World mothers didn't understand that overdilluting it—especially with contaminated water—could "prevent a child from absorbing the nutrients in food and lead to malnutrition," said War on Want.

A New York Times' article on the scandal said one Jamaican family's income "averaged only $7 a week," leading the mother to dilute the water with as much as three times the recommended amount of water so she could feed two children.

Millions of babies died from malnutrition.

YouTube / All About IBFAN"The results can be seen in the clinics and hospitals, the slums and graveyards of the Third World," said War on Want. "Children whose bodies have wasted away until all that is left is a big head on top of the shriveled body of an old man. "

"

In the Times, United States Agency for International Development official, Dr. Stephen Joseph, blamed reliance on baby formula for a million infant deaths every year through malnutrition and diarrheal diseases.

It also hindered infant growth in general, said War on Want. Citing "complex links emerging between breast feeding and emotional and physical development," the group said breastfed children walked "significantly better than bottle-fed" kids, and were more emotionally advanced.

Nestlé sued a War On Want publisher for libel in 1974.

GettyNestlé wasn't about to take these allegations lying down. It sued a German translator of War on Want's exposé, which published it in Sweden with the title, "Nestlé Kills Babies."

It sued a German translator of War on Want's exposé, which published it in Sweden with the title, "Nestlé Kills Babies."

Nestlé won the suit in 1976, said Baby Milk Action , but with a caveat: The judge urged them to "modify its publicity methods fundamentally." Time Magazine declared this a "moral victory" for consumers.

The bad publicity sparked a global boycott of Nestlé.

YouTube / All About IBFANInfant Formula Action Coalition launched a boycott in the U.S. protesting Nestlé. Soon it spread to France, Finland and Norway and countless other countries.

"I remember my mother telling me about this and in 1980, she refused to buy candy bars because we heard of so many kids dying in the news stories," said Harrigan.

The boycott was suspended in 1984, but resurfaced in the late 1980s when Ireland, Australia, Mexico, Sweden and the U.K. adopted it.

Source: Baby Milk Action

The International Code of Marketing Breast-Milk Substitutes was created in 1981.

YouTube / All About IBFANIn 1978, Senator Edward Kennedy held a series of U. S. Senate Hearings on the industry's unethical marketing practices. International meetings with the World Health Organization, Unicef and The International Baby Food Action Network followed.

S. Senate Hearings on the industry's unethical marketing practices. International meetings with the World Health Organization, Unicef and The International Baby Food Action Network followed.

By 1981, the 34th World Health Assemblyhad adopted Resolution WHA34.22, which includes the International Code of Marketing Breast-Milk Substitutes.

Celebrities like this British TV host joined the breastfeeding cause in the 1990s.

YouTube / The Mark Thomas ProductBritain's "The Mark Thomas Product" show skewered Nestlé in 1999 when its host asked heads of the company why they misrepresented their products—and labeled them in English. Didn't this take advantage of the poor and illiterate?

Didn't this take advantage of the poor and illiterate?

Here, Mark Thomas asks a "tin of baby milk from Mozambique" isn't written in Portuguese, the country's official language.

According to Baby Milk Action, Emma Thompson famously called for a boycott of the Perrier Comedy Award in 2001 since the beverage is owned by Nestlé. The following year, the Tap Water Awards were established.

Today, breastfeeding and formula remain a hot topic.

NYC Dept of Health and Mental HygieneRecently, NYC Mayor Bloomberg launched the Latch On, NYC iniative which aims to do away with formula in hospitals.

"From what I can tell, it's using the a lot of provisions in the code," said Harrigan.

Not even your kitchen is safe ...

Flickr / Nomadic LassRead next

LoadingSomething is loading.Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you're on the go.

More...

South Africa Baby Food Market Report 2022: Featuring Key Players Nestle, Orchard Baby Food, Bumbles Baby Food, Abbott & The Baby Food Company - ResearchAndMarkets.com

DUBLIN--(BUSINESS WIRE)--The "South Africa Baby Food Market - Forecasts from 2022 to 2027" report has been added to ResearchAndMarkets.com's offering.

The growth is attributed to the rising disposable income and the unwillingness to compromise on baby products. The presence of key market players in the region is also a factor boosting the baby food market growth.

Drivers

As baby food is one of the prime substitutes for breastfeeding, the demand for baby food is mainly from working women with infants and the share of working women in South Africa has been rising in the last few years.

According to a World Bank report, the total percentage of labour females increased to 45.3% in 2019. And due to a suitable educational environment, this share is anticipated to increase in upcoming years. Thus, the demand for baby food from this population is expected to grow at the same pace. Because of this, the baby food market is expected to grow during the forecast period as well.

In addition to this, the overall population of South Africa has also been rising at a faster pace in the last few years. According to the World Bank report, the total population of South Africa was 59 million in 2020. This population growth is expected to drive the demand for baby products with rising demand for baby food products, which is projected to boost the market value of the baby food market in upcoming years.

Restraints

The South African government has put forth regulations on promoting breastfeeding in the country. Hence, the advertisement of infant formula is not supported due to such regulations.

The demand for baby food products is anticipated from the urban areas of the country. Areas such as Cape Town are projected to hold a prominent share in the baby food market in South Africa. Hence, it is expected to grow its market share during the forecast period.

Market Segmentation:

By Type

- Organic Baby Food

- Non-organic Baby Food

By Product

- Dried Baby Food

- Milk Formula

- Prepared Baby Food

- Others

By Distribution Channel

- Online

- Offline

Key Topics Covered:

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

3. Executive Summary

Executive Summary

3.1. Research Highlights

4. Market Dynamics

4.1. Market Drivers

4.2. Market Restraints

4.3. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

4.4. Industry Value Chain Analysis

5. South Africa baby food Market Analysis, by Type

5.1. Introduction

5.2. Organic baby food

5.3. Non-organic baby food

6. South Africa baby food Market Analysis, by Product

6.1. Introduction

6.2. Dried baby food

6.3. Milk formula

6.4. Prepared baby food

6.5. Others

7. South Africa baby food market, by Distribution Channel

7.1. Introduction

7.2. Online

7.3. Offline

8. Competitive landscape and analysis

8.1. Major Players and Strategy Analysis

8.2. Emerging Players and Market Lucrativeness

8.3. Mergers, Acquisitions, Agreements, and Collaborations

8. 4. Vendor Competitiveness Matrix

4. Vendor Competitiveness Matrix

9. Company Profiles

9.1. Nestle

9.2. Orchard Baby Food

9.3. Bumbles Baby Food

9.4. Abbott

9.5. The Baby Food Company

Companies Mentioned

- Nestle

- Orchard Baby Food

- Bumbles Baby Food

- Abbott

- The Baby Food Company

For more information about this report visit https://www.researchandmarkets.com/r/ahyadb

Nestlé for babies, or how to run the perfect third world marketing campaign

Baby food is an emotional topic. It is unlikely that anyone will deny that breast milk is the healthiest, cheapest and safest product for feeding babies. However, it is known that for various reasons, not all mothers are able to feed their children with their own milk. Medical contraindications, lack of education or the need to go to work forced women to look for an alternative to breastfeeding babies. nine0003

nine0003

In 1867, Nestlé was the first to develop and market baby food for premature babies. Even then, it was recognized that breastfeeding is ideal for the baby, and artificial formula is suitable only when the mother has no other choice. However, the invention of Henry Nestle was a real salvation for premature babies who were unable to take any other food. Over time, Nestlé has become the world's largest manufacturer of powdered infant formula. nine0003

Description of the problem

Baby food sales skyrocketed in the post-war years as a consequence of the so-called post-war baby boom. Since the late 1950s, however, a decline in the birth rate began, which could not but affect income from the sale of food. In desperation, turning their eyes to the developing countries of Africa, South America and the Far East, industrialists realized that with the development of new markets, a successful future awaited them.

In the second half of the 20th century, the sociocultural situation began to change in poor countries. Women, who provided a significant part of the family income, began to meet more and more often. In order not to lose their place, after the birth of a child, they sought to return to work as soon as possible. nine0003

Women, who provided a significant part of the family income, began to meet more and more often. In order not to lose their place, after the birth of a child, they sought to return to work as soon as possible. nine0003

Purpose

The forthcoming marketing campaign was intended to:

- to popularize artificial feeding;

- Convince the target audience that powdered formula is better for infant feeding than breastfeeding;

- Increase sales of Nestlé's powdered baby food formulas.

Target audience

breastfeeding mothers, physicians, medical staff in maternity wards, pharmacists, employees of courses for new mothers. nine0003

Period

The 1960s are our time.

Tools

ATL (radio, press, outdoor advertising), BTL (sampling, promotions, direct marketing), brainwashing, lobbying.

Solution

Direct consumer promotion of dry formulas for artificial feeding in the third world countries was very diverse. Nestlé chose radio, newspapers, magazines, billboards and loudspeaker vans as its main advertising media. Samples, bottles, nipples and measuring spoons were generously distributed. nine0003

Samples, bottles, nipples and measuring spoons were generously distributed. nine0003

So, what was the content of the campaign itself, and, accordingly, the advertising media?

• Marketing methods were designed to mislead poor and illiterate mothers into thinking that artificial feeding was preferable to natural feeding;

• Booklets ignored or did not highlight the benefits of breastfeeding;

• Advertisements portrayed breastfeeding as old-fashioned and uncomfortable;

• Gifts and trial samples were intended as a direct incentive to formula feed. nine0019 • Active placement of advertising in hospitals implied that the product was approved by the health system.

The practice of free or subsidized supplies of artificial milk to hospitals and maternity wards has also been adopted. This encouraged artificial feeding of children, but disrupted the proper functioning of the mammary glands. The calculation was that when the mother left the hospital, she could not re-transfer to breastfeeding, respectively, became a regular customer of the company's products. nine0003

nine0003

About two hundred women were employed by Nestlé as promotional personnel, so-called "milk nurses", who were registered with hospitals as nurses, diet nurses, or midwives. These "sisters" were uniformed sales associates who visited mothers and gave them food samples in an attempt to convince them of the benefits of artificial feeding.

In addition to direct consumers, the company's advertising efforts were directed at doctors and other medical personnel. This type of marketing involved discussing product quality and performance with paediatricians, nurses, and other maternity staff. Materials such as advertisements, charts, and free samples have been made available to doctors, hospitals, and free clinics. Doctors and other hospital staff were paid by the firm to travel to medical conferences. nine0003

Nestlé now distributes posters and brochures to the Gabon healthcare system to promote powdered formula, distributes a type of formula, "Cerelac", gives gifts to healthcare workers, and supports travel and conferences.

In India, the company became the only baby food advertiser in the Indian edition of Parenting magazine. In addition, in order to be able to advertise "Cerelac" in Indian pharmacies, Nestlé pays local pharmacists an average of Rs 200 per month. A similar practice is carried out by the company in countries such as Chile, Colombia, Zimbabwe. nine0003

Campaign results

Thanks to Nestlé's marketing and promotional methods, dry mixes as a product have gained a certain prestige. And what could be more natural than a mother's desire to give her baby all the best. Thus, the “positions” of breastfeeding were undermined. In 1951, approximately 80% of three-month-old babies in Singapore were breastfed. In 1971 - only 5%.

By the mid-1970s, powdered infant formula was the third most advertised product in the Third World, after tobacco and soap. Sales of Nestlé baby food in poor countries have skyrocketed. nine0003

In 1978, the company's annual turnover amounted to 11 billion dollars, and 31% of total sales at that time were in the third world countries. By comparison, 46% were in Europe and 20% in North America. Approximately the same were the indicators for the segment of dry mixes for feeding infants.

By comparison, 46% were in Europe and 20% in North America. Approximately the same were the indicators for the segment of dry mixes for feeding infants.

It is not yet possible to sum up the final results of the massive campaign to promote powdered infant formula in the countries of the "third world", since the "program" has not yet ended. nine0003

But seriously, the results are...

According to the World Health Organization, 1.5 million children die every year from unsafe formula feeding (most of them in Third World countries). And this means that one baby dies from improper feeding in 30 seconds. For at least the first 6 months of life, infants are recommended to be fed exclusively with breast milk. Introduction to the diet of products other than breast milk in the first months of life increases the risk of various diseases. nine0003

It was not until the early 1970s that the first suspicions began to arise among the world community that baby food manufacturers, by vigorously promoting their product to Third World countries, contributed to a high percentage of infant mortality. Most of the end users were simply unable to read the manual due to the high illiteracy rate in those countries. In addition, Nestlé printed product instructions only in English prior to the relevant legislation. nine0003

Most of the end users were simply unable to read the manual due to the high illiteracy rate in those countries. In addition, Nestlé printed product instructions only in English prior to the relevant legislation. nine0003

Many consumers have been unable to use the product correctly due to living conditions, mixing food with dirty water or pouring the mixture into unsterilized bottles. Yet, according to UNICEF, an unhygienic artificially fed infant is at least 6 times more likely to die from diarrhea and 4 times more likely to die from pneumonia than a breastfed infant.

Equally problematic was that baby food was too expensive and many customers diluted it to useless levels. Accordingly, the baby's nutrition was inadequate. nine0003

New mothers were not informed that all the essential nutrients and antibodies found in mother's milk are almost entirely absent from powdered formulas. Criticism was based on the fact that the company did not warn mothers about the possibility of artificial feeding only in emergency cases (for example, if a woman had to go to work soon, or if she was physiologically unable to breastfeed).

Nestle boycott

B 19'74 British charity War on Want publishes a 28-page document entitled "Babykiller" that publicly criticizes the marketing methods used by the Swiss company Nestlé in Africa for the first time. A year later, the German Third World Working Group accused Nestlé of "unethical and immoral behavior" in its article "Nestlé kills babies".

In 1977 two public interest groups, the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility and the Infant Formula Action Coalition (INFACT), announce a worldwide boycott of Nestlé. The movement soon gains support from over 450 local and religious groups across America, with supporters claiming it is the largest non-union boycott in United States history. nine0003

It was the worldwide boycott of Nestlé that led to the adoption in 1981 of the WHO International Code for the Marketing of Formula Feeding. Under the Code, baby food companies must not:

• Supply infant formula to hospitals;

• Advertise your products to community or health professionals;

• Use pictures of babies on baby food labels;

• Give gifts to mothers or health workers; nine0019 • Give free product samples to parents;

• Advertise meals for children under 6 months of age.

Baby food labels must be in a language that the mother understands and contain an important warning about the contraindications and consequences of formula feeding.

New concept

However, as you probably already understood, Nestlé only declaratively supported the Code. In practice, the company tries in every possible way to circumvent its regulations. The company developed the concept that infant formula saves lives, not takes them - a hint that those children who cannot be breastfed for various reasons are no longer doomed to die. The problem is that Nestlé did not present this idea in a clear and understandable form in the early stages of the crisis. On the other hand, despite the new concept, the company's violations of various ethical and legal norms continue. nine0003

It wasn't until the early 1990s that Nestlé began to communicate with its stakeholders much more intelligently. A significant number of materials have been published, refuting the accusations against the company and restoring the truth as it is seen by the company. In essence, these were elements of a defensive strategy that left control of the problem at the mercy of groups of social activists who were aggressively disposed against the TNC itself. Partly to repair a damaged reputation, Nestlé launched a new marketing strategy in 2002 called Good Food. Good Life, which focuses on the health of consumers. nine0003

In essence, these were elements of a defensive strategy that left control of the problem at the mercy of groups of social activists who were aggressively disposed against the TNC itself. Partly to repair a damaged reputation, Nestlé launched a new marketing strategy in 2002 called Good Food. Good Life, which focuses on the health of consumers. nine0003

A similar story can be told about almost any transnational corporation in the world. And for Nestlé, she is not the only one. And this company, frankly, was simply unlucky, but it is not surprising that Nestlé, which controls half of the baby food market, was the first to be boycotted. Later, other baby food manufacturers were blacklisted by consumer advocacy groups for violating the Code and being subject to boycotts of their products: Abbott Ross, Mead Johnson, and Danone. nine0003

This is the world we live in. In it, all means are good to achieve the goal and to make a profit. You can take it easy, live with it. And you can choose a different path.

In 2005, three years after Nestlé had positioned itself as a health food manufacturer, research company GMI conducted a survey of 15,500 people in 17 countries about the image of leading multinational corporations. Nestlé has been voted the most boycotted company in the world. For example, 21% of the French and 36% of the Italians declared their rejection of Nestlé. nine0003

Today, Nestlé is experiencing a total consumer boycott of all its products in 18 countries - Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Mauritius, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom and USA. Boycott supporters say they will stop protesting the company only if it actually starts to comply with the WHO International Code.

Sources

Andrew Griffin, Reputational Risk Management, Alpina Business Books, 2009

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nestlé_boycott#The_baby_milk_issue

http://www.createbrand.ru/biblio/branding/33nestle. html

html

http://www.babymilk.nestle.com/

http: //en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Alliance_for_Breastfeeding_Action

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Code_of_Marketing_of_Breast-milk_Substitutes

http://www.ibfan.org/english/pdfs/btr04/btr04nestle.pdf

http: //www.kommersant.ru/doc.aspx?DocsID=894932

Skobkarev Evgeniy, 4th MJ MGIMO

Tags: bad guys, case study, fmcg, international, pr, sale, kids, marketing

Memories of the Nestlé infant formula scandal that rocked the 1970s

However, faced with depopulation in the Western world in the 1960 's, mix sales fell. Infant formula companies had to find a new market for their product. Some companies, such as Nestlé, have reached out to developing countries by providing mothers with promotional materials and samples to teach them the new method of feeding their babies. nine0003

However, Nestlé infant formula has had a terrible impact on Africa, South America and South Asia. The number of lives lost associated with Nestlé infant formula skyrocketed, leading to a boycott of the Nestlé company in the 1970s. The boycott did not end the problem, but rather spurred the call for international standards for infant formula.

The boycott did not end the problem, but rather spurred the call for international standards for infant formula.

An even more recent "water scandal" in Africa is reminiscent of the Nestlé infant formula predicament. Both of these stories prove that corporate interests, namely making money, often win over elementary human concern. nine0003

Nestlé sued the publisher for claiming "Nestlé kills babies" and won

The first noteworthy article on Nestlé's methods of distributing infant formula in third world countries was published in the New Internationalist in 1973 year under the title "Children are business". The article accused Nestlé of three things when it came to their business practices in third world countries:

“Creating a need where there was none. nine0003

Convince the consumer that our product is indispensable.

Associate a product with the most desirable and unattainable concepts - and then provide a sample.

The 1974 British edition of The Baby Killer pamphlet was another tool that sparked the worldwide debate about infant formula. When a German publisher translated the booklet, changing the title to Nestlé Kills Children, Nestlé sued for defamation. The parties spent two years in litigation, and in the end Nestlé won the lawsuit. However, the judge convinced Nestlé to adjust the advertising and publications. nine0003

When a German publisher translated the booklet, changing the title to Nestlé Kills Children, Nestlé sued for defamation. The parties spent two years in litigation, and in the end Nestlé won the lawsuit. However, the judge convinced Nestlé to adjust the advertising and publications. nine0003

Nestlé saleswoman dressed as a nurse told mothers about the benefits of infant formula

When Nestlé and other dairy companies began to introduce their products to developing countries, they launched a full-scale campaign by dressing their representatives in nurse uniforms and sending them to lure customers .

These so-called "milk nannies" visited homes and hospitals to talk about their innovative formulas, and while some of them may have been educated, most of them were not. They spent time in maternity hospitals giving advice on nutrition and feeding, as well as giving mothers instructions on how to prepare infant formula. nine0003

In Singapore, milk nannies were so widespread that they were banned from visiting hospitals. As a result, these nannies simply waited outside for the new mothers to come out and then provided samples of infant formula.

As a result, these nannies simply waited outside for the new mothers to come out and then provided samples of infant formula.

In Jamaica, milk nannies could get the names of new mothers and visit their homes. In the Philippines, milk nannies visited government housing, finding homes with newborns and young children by diapers hanging from clotheslines.

Mothers reduced the nutritional value of infant formula by diluting it with water

When mothers became dependent on infant formula, the cost of the product became a problem. As a result, many women have begun to dilute the mixture so that it lasts longer. They added three times the recommended amount of water, which seriously reduced the nutritional value of the mixture.

When researchers in Indonesia studied this phenomenon, they found that "only one in four women diluted the mixture close enough to the recommended concentration." At a meeting of the Health and Research Committee held in the United States on 19In 1978, Dr. Alan Jackson testified that mothers "stretched" cans of formula, which should have lasted three days for one child, up to two weeks while feeding two children the contents of one can.

Alan Jackson testified that mothers "stretched" cans of formula, which should have lasted three days for one child, up to two weeks while feeding two children the contents of one can.

Babies in developing countries made sick by contaminated water

Mothers in developing countries used water containing faecal organisms, among other contaminants, when mixing formula. When a Peruvian nurse named Fatima Patel testified before a U.S. subcommittee at 1978, she shared how difficult it would be to find clean water for infant formula:

"The river is used as a laundry, as a bathroom, as a toilet and as a source of drinking water ... also we can say ... to get fuel for boiling of this water, the woman must go into the jungle, cut down the trunk of a tree with a machete ... and bring it on her back. No mother would use this hard-earned piece of wood to boil water. Thus, babies drink contaminated water." nine0003

In addition, the bottles used for formula have not been sterilized. Despite labels on formula jars and instructions from milk nannies, women often lacked heating methods sufficient to sterilize bottles - alternatively, a few people could only access one pot, resulting in insufficient resources to properly sterilize a bottle. .

Despite labels on formula jars and instructions from milk nannies, women often lacked heating methods sufficient to sterilize bottles - alternatively, a few people could only access one pot, resulting in insufficient resources to properly sterilize a bottle. .

Nestlé attracted mothers and babies with free samples

Nurses distributed free samples of formula to new mothers, giving them the option to either stop breastfeeding or use formula in combination with breastfeeding. nine0003

However, when the baby is breastfed less or stops breastfeeding, the mother's milk gradually dries up. This led to an inevitable dependence on formula milk.

Although financial dependence was significant, equally important was the lack of nutrients and antibodies that infants received from breast milk. Scientists have recognized the importance of colostrum, a milk-like substance produced by a mother shortly after a baby is born, in building a baby's immune system. As infants began to breastfeed less, the overall health of infants in third world countries began to deteriorate. nine0003

As infants began to breastfeed less, the overall health of infants in third world countries began to deteriorate. nine0003

WHO and UNICEF linked infant mortality to infant formula started collecting data.

They found that millions of babies were dying from malnutrition and diarrhea caused by diseases such as kwashiorkor (a type of severe malnutrition) and alimentary insanity (alimentary dystrophy) caused by protein deficiency. Doctors have linked these ailments to the increased use of infant formula. Due to the growing reliance on infant formula, babies' immune systems were less able to develop, fight disease, and allow the baby to survive infancy. nine0003

Doctors have even coined the term "weaning diarrhea", defined as "a collection of illnesses in an infant described as a weaning syndrome". This is due to the introduction of other foods and the loss of the protective properties obtained with breast milk.

Formula companies made mothers question their own ability to care

Formula companies used the so-called "confidence trick" to tell mothers that they should be aware of the possibility of their babies being malnourished. This tactic will create fear or anxiety in mothers and make them question their ability to produce enough breast milk for their babies and encourage mothers to start using formula as an alternative. As a result, their breast milk gradually dried up. nine0003

This tactic will create fear or anxiety in mothers and make them question their ability to produce enough breast milk for their babies and encourage mothers to start using formula as an alternative. As a result, their breast milk gradually dried up. nine0003

Mothers in developing countries, especially in the 60s and 70s, had little doubt about their ability to breastfeed until they had an alternative. As soon as the mother stopped breastfeeding, even temporarily, she was forced to feed her baby with formula milk.

As the pamphlet Baby Killer puts it, "Somehow mothers decide that a bottle is necessary for the milk she gives... some mothers may even be so concerned about not having enough milk that they won't have any." . nine0003

Western culture bombarded women with marketing in the 1970s

Another key element in the transition from breastfeeding to formula feeding in developing countries was the advertising of Nestlé and other formula manufacturers. Many women moved to the cities in the 1970s, where they were bombarded with messages, both overt and covert, that bottle-feeding was both modern and "Western."

Many women moved to the cities in the 1970s, where they were bombarded with messages, both overt and covert, that bottle-feeding was both modern and "Western."

Both print and broadcast media in developing countries such as Brazil "where infant formula was the most advertised product after cigarettes and soap ... promised, albeit subtly, that formula was a modern method of infant feeding associated with mobility, and that she would produce plump-cheeked children."

Companies bribed clinics and hospitals with free food and financial incentives

In many developing countries, Nestlé and other dairy companies supplied clinics and hospitals with large amounts of formula every year. This encouraged institutions to pass on the formula to their patients, but also attracted the medical community to the corporate plan.

In Nigeria, clinics received up to "8,000 free cans of infant formula annually." In Ethiopia, India and other parts of the world, companies have also given free bottles and other gifts to clinics and hospitals to encourage breastfeeding. Still later, formula companies began donating large sums to hospitals and physicians, with the companies spending "untold millions of dollars to subsidize office furniture, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications, and medical professional travel." nine0003

Still later, formula companies began donating large sums to hospitals and physicians, with the companies spending "untold millions of dollars to subsidize office furniture, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications, and medical professional travel." nine0003

Infant formula companies set standards in formula in the early 1980s

In 1980, the World Health Assembly adopted WHO and UNICEF recommendations on international infant feeding practices. Although they released an official code the following year, Nestlé and three other companies publicly stated their unwillingness to follow any official policy.

In the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes adopted by the World Health Assembly at 1981, stated that baby food companies should not have direct contact with mothers, hospitals or health care workers - especially with gifts - they should not provide misleading information and their product labels should be clear and contain appropriate warnings. Companies also had to explain the costs of using mixtures. Countries around the world began to adopt the Code, and companies soon agreed. In the end, Nestlé agreed to follow the Code at 1984 year. However, this policy has hardly been enforced and companies continue to break and break the rules.

Companies also had to explain the costs of using mixtures. Countries around the world began to adopt the Code, and companies soon agreed. In the end, Nestlé agreed to follow the Code at 1984 year. However, this policy has hardly been enforced and companies continue to break and break the rules.

The worldwide boycott of Nestlé began in 1977 and continued until 1984.

In the 1970s, the personal is political movement brought renewed attention to breastfeeding on a global scale. The 1970s saw increased concern about women and babies in Third World countries, where breastfeeding had declined significantly over the previous decade. nine0003

Researchers studied this and the associated rise in bottle feeding, eventually finding that not only misuse of infant formula leads to infant illness and death, and that mothers are misled about the effectiveness of formula. The study resulted in a boycott of Nestlé, which had "81 factories in 27 developing countries and 728 sales centers in all parts of the world promoting their products. "

"

In the United States the Infant Formula Action Coalition announced a boycott that quickly spread to parts of Europe, Canada and Australia. Between 1977 and 1981, the Nestlé company tried to solve problems and restore its image; meanwhile, the International Infant Food Surveillance Network (IBFAN), a group of six anti-Nestlé organizations, formed and fought to oversee the infant formula industry.

Although International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was adopted in 1981, Nestlé did not agree to follow it until 1984. This boycott ended.

The boycott resumed in the late 1980s and continues to this day

The Nestlé boycott was renewed in 1988. Since then, more than 20 countries have boycotted Nestlé's subsidiaries due to their persistent attempts to circumvent International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes . The non-profit organization Baby Milk Action insists that the boycott will continue until Nestlé agrees to follow their four-point action plan. nine0003

nine0003

Nestlé has a policy of its own, but continues to face allegations of selling "substandard" infant formula in South Africa. In February 2018, Nestlé was accused of not including important ingredients in its product in South Africa, as well as of "a strategy to increase profits by trying to convince parents to buy more expensive products, believing that they are better for their child's health".

Nestlé also caused Fanta Syndrome

Infant formula is not the only product that major Western companies have introduced in less developed countries with detrimental health effects. At 1974 in Africa was diagnosed with "Fanta Syndrome", named after the orange carbonated drink Coca Cola. The lack of suitable alternatives to baby food, as well as a misunderstanding of the product's intended purpose, only exacerbates the problem.

Nestlé has also become embroiled in a water dispute. The company has been accused of selling Pure Life water to countries in dire need such as Pakistan and Nigeria, but making it too expensive for most consumers, proving once again that profit, not care, is the world's greatest driving force.