Pre chewing food for baby

Pre-Chewing Food For Babies: The Research Continues

On a trip to a society of forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon a few years ago, Melanie Martin asked a dozen Tsimane mothers to chew up their food and spit it into a cup — instead of their babies’ mouths. The Tsimane, like certain cultures around the world, feed their babies through premastication. When asked why they pre-chewed meals, responses varied.

“They’re just making sure there’s nothing in that spoonful that is going to burn the kid’s mouth or choke them,” says Martin, who visited the group when she was a graduate student in anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Martin is part of a small group of researchers actively studying — and sometimes even trying — this ancient feeding practice. Ethnographers have documented premastication on every continent and in every type of society from hunter-gatherers to farmers. It remains surprisingly common in parts of the world today. Eighty percent of babies in Nigeria receive pre-chewed food, as do a quarter of infants in Gabon. Field workers have observed the practice throughout East and South Asia. Among HIV-infected mothers in Argentina, Brazil and Peru, many have heard of premastication, while 4 percent practice it. And in the United States, 1 in 7 caregivers — particularly black caregivers — report pre-chewing food.

Despite the prevalence, few leading public health agencies mention premastication in their guidelines and those that do discourage it due to a host of potential health risks.

Premastication is conspicuously absent from the World Health Organization’s literature on introducing babies to solid foods. (WHO spokesman Christian Lindmeier said an expert was unavailable to comment on the issue.) Meanwhile, the American Academy of Pediatrics advises against the practice due to the risk of disease transmission. While not addressing premastication directly, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry cautions against sharing utensils among family members.

Researchers have linked premastication to the spread of HIV, hepatitis B, dental caries, and syphilis from caregiver to baby. But beyond single-pathogen studies, broader inquiry into the practice such as its possible role in nutrition, immune health and parental bonding remains woefully scant.

But beyond single-pathogen studies, broader inquiry into the practice such as its possible role in nutrition, immune health and parental bonding remains woefully scant.

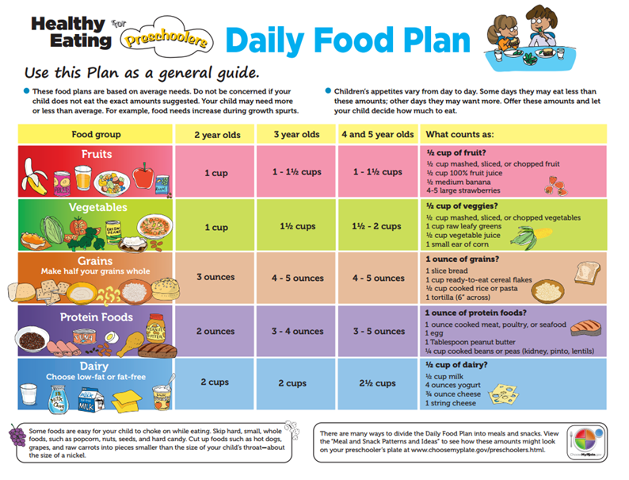

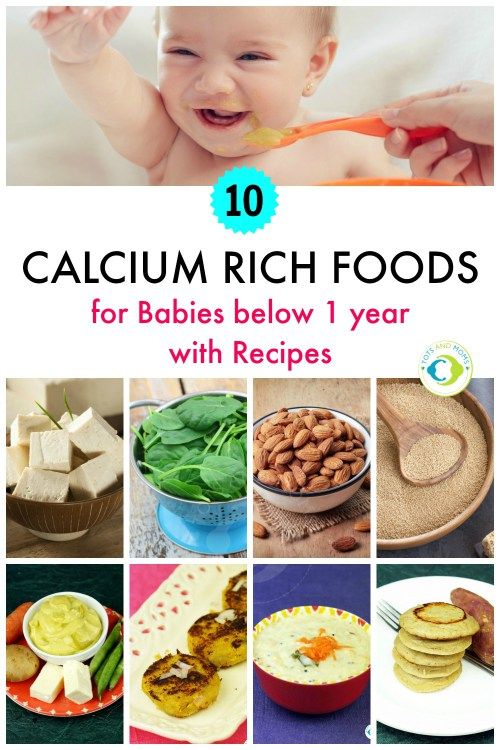

Breast milk alone ceases to meet a baby’s nutritional needs around 6 months of age. But it takes up until about age 2 for babies to grow a full set of teeth. For over a year, babies occupy a nutritional gray zone. They can neither thrive on milk alone nor eat adult foods without modification such as blending, boiling or chopping. The rising popularity of baby-led weaning, or letting babies feed themselves from the adult table, partly circumvents these challenges. But foods rich in micronutrients that are a potential choking hazard, such as raw vegetables, chewy meats and nuts, remain a difficulty.

In 2010, epidemiologist Jean-Pierre Habicht and his wife, anthropologist Gretel Pelto, of Cornell University, hypothesized that premastication arose to close that nutritional gap. Writing in Maternal & Child Nutrition, they proposed that premastication may be as vital to child health as breastfeeding.

In developed countries, many older babies meet their nutritional needs with fortified foods such as Gerber and Cheerios. But in developing nations, where access to fortified foods remains limited and infections run rampant, physical and intellectual stunting is widespread, particularly in babies just starting on solids.

Nutrition aside, Habicht and Pelto further argued that because breast milk and saliva share many of the same antibodies, the beneficial bacteria present in premasticated food may protect against disease. The couple’s ideas created a stir, prompting the journal to publish six commentaries from prominent researchers on both sides of the premastication divide.

“The campaign against the barbaric practice of premastication,” Habicht says, “is very similar to the campaign in the 30s and 40s against the barbaric practice of breastfeeding.”

Researchers studying premastication suspect that Paleolithic parents pre-chewed vegetables, nuts and hunks of meat for their offspring. But it’s impossible to prove since pre-chewing leaves no archaeological trace.

But it’s impossible to prove since pre-chewing leaves no archaeological trace.

The first known written record of the practice appears in 1025 AD. “After the first two teeth have appeared, a progressively stronger aliment [than breast milk] is to be considered,” wrote the Persian philosopher Avicenna in his five-part Canon of Medicine. “Hard things, however, must not be allowed. At first, bread is given which the nurse has masticated.”

By the 1600s, concerns over premastication had begun to emerge. Though noting that the common practice may aid in digestion, the German physician Michael Ettmüller cautioned that, should a caregiver’s gums be infected, the child may also receive that “morbificial Tincture.”

By the 20th century, evidence suggests the practice was being actively snuffed out. In the 1940s, researchers from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque studying the displaced Shoshone Native Americans in Nevada found that mothers exclusively nursed their babies until they were able to eat on their own, or around age 1 or 2. That delayed start to solids was leading to high rates of anemia. “Some Indians informed the investigators that in the past their parents used to chew food and then place this previously masticated food in the infant’s mouth,” the authors wrote in The Journal of Nutrition in 1943. “Such a process was considered unhygienic by the invading culture and the practice was abandoned.”

That delayed start to solids was leading to high rates of anemia. “Some Indians informed the investigators that in the past their parents used to chew food and then place this previously masticated food in the infant’s mouth,” the authors wrote in The Journal of Nutrition in 1943. “Such a process was considered unhygienic by the invading culture and the practice was abandoned.”

In more recent years, premastication briefly became a buzzword in 2012 when Clueless star Alicia Silverstone posted a video of herself chewing the vegetables in her miso soup and transferring the resulting blob into her 10-month-old son’s mouth. The video went viral and prompted a range of reactions from disgust to solidarity.

As a nutrition expert with the United Nations, Joel Conkle was aware that mothers and grandmothers in Cambodia would often pre-chew food before giving it to babies. In 2014, he enrolled in a doctoral program at Emory University in Atlanta to study premastication full-time.

Earlier this year, Conkle and his colleagues combed through data from a national survey collected when babies were 10 months old, the age at which premastication tends to peak. Of the 1,770 women who responded at that point, 203 reported pre-chewing food in the previous two weeks. Conkle measured the prevalence of diarrhea in both groups: About 11 percent of babies in the conventional feeding group developed diarrhea compared to about 16 percent of babies in the premastication group.

Since diarrhea is one of the leading causes of death in children, the finding is particularly troubling for low-income countries. Even when it’s not lethal, chronic diarrhea puts infants at risk for malnutrition, says Conkle, who published the results online in Maternal & Child Nutrition last week.

Past studies have linked premastication to the transfer of various pathogens from caregiver to baby. A 2009 case study involving three U.S. children found evidence of HIV transmission when infected caregivers fed pre-chewed food to babies. That prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to advise caregivers with HIV to avoid premastication.

That prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to advise caregivers with HIV to avoid premastication.

“Where safe, affordable, alternative feeding options are available, HIV-infected caregivers should refrain from this practice,” says Aditya Gaur, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee and the lead author on the HIV study.

But Cornell researchers Habicht and Pelto argue that the tendency to focus on a single pathogen or disease obscures the larger role premastication may play in nutrition and immune health. The duo has found an unexpected ally among supporters of the so-called hygiene hypothesis, which proposes that asthma, irritable bowel syndrome and allergies are rising in wealthy countries due to an overly sterile, or low-bacteria, environment.

Several years ago, Swedish researchers found that babies born to parents who cleaned their pacifiers by sucking on them had lower rates of allergies and eczema than babies born to parents who exclusively cleaned pacifiers with soap and water. Premasticated food may likewise be good for children, at least in wealthy areas, says Bill Hesselmar, a pediatric allergist at the University of Gothenburg and the study’s lead author. “If you worry too much,” he says, “you won’t even kiss your child.”

Premasticated food may likewise be good for children, at least in wealthy areas, says Bill Hesselmar, a pediatric allergist at the University of Gothenburg and the study’s lead author. “If you worry too much,” he says, “you won’t even kiss your child.”

Deep in the rainforest, the Tsimane (pronounced chee-MAH-nay), tend to subsist on what they fish or hunt, and what they can grow, which includes rice, plantains, and manioc, a root vegetable also known as cassava. Their signature dish is jo’na – a stew made with manioc and meat or fish that when caught fresh is slow roasted for days and generously seasoned. Nowadays, the Tsimane visit regional markets and stock up on starches like pasta and charqie, a tough dried meat similar to beef jerky, which they then add to the jo’na.

“Basically they eat variations of the same stew with meat or fish and not really any flavoring except for a ton of salt,” says Martin, now an anthropologist at Yale University, who describes the stew as bland but delicious.

Over her lifetime, the average Tsimane woman bears nine children and breastfeeds exclusively until the baby reaches a few months old. At that point, many mothers start setting the babies on their laps during meals and feeding them pre-chewed food.

A few years ago, Martin along with Cliff Han, a geneticist at Los Alamos National Laboratories in New Mexico, collected saliva from 12 mother-baby pairs as well as premasticated jo’na samples from the mothers. Han then analyzed the bacteria in the samples in the lab.

Previous research has shown that bacteria, such as cavity-causing Streptococcus mutans, can travel from mother to child. Cavities are common in Tsimane children and their mothers. Toothbrushing is rare as is basic dental health care, Martin says, so “their teeth are awful.”

Han’s analysis showed that, at least up until age 2, it was impossible to identify mother-baby pairs through their oral bacteria, including Streptococcus mutans. In many cases, the strep was high in the mother but low in the baby. (In one case, Han found a baby with a high strep load and a mother with a low load.)

(In one case, Han found a baby with a high strep load and a mother with a low load.)

This means that tooth decay is likely arising from a different source than premasticated food. “Even though the mother feeds her microbiome to the baby, not everything can attach,” says Han, who presented the team’s findings at the Human Biology Association conference in Calgary, Canada in 2014.

For her part, Martin says she became pregnant while traveling with her husband to Tsimane territory three years ago, and that they decided then to follow the local eating tradition and pre-chew food after their daughter was born. “Spending all this time with Tsimane moms and watching how they feed their kids,” she recalls, “my one takeaway was that my kid was going to grow up sitting in my lap and eating everything that I eat.”

“It’s just like the laziest, easiest thing you can do,” she adds. “You never have to make kid food.”

Conkle says his wife briefly experimented with premastication as well — there is no known evidence for male pre-chewers — but it didn’t last. As he researched the practice, he began to question the purported benefits, particularly in the modern world. What is rarely mentioned, he says, is whether or not the mother is still breastfeeding, which would create a different suite of bacteria in the mouth and gut than babies who have weaned. Comparing and contrasting the various sorts of foods being pre-chewed is also largely unexamined, he says. Pre-chomping on a goldfish cracker, for instance, would yield none of the nutritional benefits found in meat or nuts, plus the starches would increase a child’s likelihood of developing cavities.

As he researched the practice, he began to question the purported benefits, particularly in the modern world. What is rarely mentioned, he says, is whether or not the mother is still breastfeeding, which would create a different suite of bacteria in the mouth and gut than babies who have weaned. Comparing and contrasting the various sorts of foods being pre-chewed is also largely unexamined, he says. Pre-chomping on a goldfish cracker, for instance, would yield none of the nutritional benefits found in meat or nuts, plus the starches would increase a child’s likelihood of developing cavities.

“When I looked at the evidence, I couldn’t really say if [premastication] was a good idea or a bad idea,” Conkle says, though he adds that the real reason premastication never took root in his household likely had less to do with science than upbringing.

“We didn’t premasticate regularly,” he says, “mostly because it’s not part of our current culture.”

Sujata Gupta is a Vermont-based science journalist. Her work has appeared online and in print in The New Yorker, New Scientist, Nature, High Country News, Scientific American, Wired, and Psychology Today among other publications.

Her work has appeared online and in print in The New Yorker, New Scientist, Nature, High Country News, Scientific American, Wired, and Psychology Today among other publications.

Should You Pre-Chew Your Baby's Food?

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Pre-chewing your baby's food can boost his or her immune system. (Image credit: <a href="http://image.shutterstock.com/display_pic_with_logo/187633/187633,1215124044,1/stock-photo-mother-feeding-baby-food-to-baby-14501131.jpg">Image</a> via Shutterstock)The actress Alicia Silverstone got a lot of grief last week after posting a video to her blog in which she is shown "pre-chewing" her baby's food, and offering it to him straight from her mouth. The "Clueless" star's 10-month-old son, Bear, appears to enjoy being fed like a baby bird. "He literally crawls across the room to attack my mouth if I'm eating," Silverstone blogged.

While most people who commented on the video were quick to voice their disgust and vilify the ill-considered whims of celebrity parents, science suggests that "pre-mastication," or the pre-chewing of adult food for infants, is actually a traditional and healthy feeding method. Standard practice among our blender-lacking ancestors, pre-chewing is still the norm in many non-Western cultures. The act exposes infants to their mothers' saliva, giving them an immune system boost that they can't get from the sterile, pulverized baby food bought in stores.

The benefits of pre-chewing have only recently been investigated, but they appear to parallel those of breast-feeding.

Babies start requiring non-milk food in their diets at six months old, but they don't develop the molars they need to chew most foods until age 18 to 24 months. According to research led by Gretel Pelto, an anthropologist at Cornell University, pre-mastication was the solution to feeding infants during this interim period for most of human history, and remains the method used in many cultures today.![]() Rather than being unhygienic, Pelto and many other scientists think the feeding method carries on the immune-system-building process that begins with breastfeeding. By exposing infants to traces of disease pathogens present in a mother's saliva, it gears up their production of antibodies, teaching their immune systems how to deal with those same pathogens later. [Could Humans Live Without Bacteria?]

Rather than being unhygienic, Pelto and many other scientists think the feeding method carries on the immune-system-building process that begins with breastfeeding. By exposing infants to traces of disease pathogens present in a mother's saliva, it gears up their production of antibodies, teaching their immune systems how to deal with those same pathogens later. [Could Humans Live Without Bacteria?]

It may also prevent the onset of autoimmune diseases, such as asthma, that are very common in industrialized societies. These conditions arise when one's immune system mistakenly attacks one's own cells, and such ailments have been strongly linked to underexposure to diseases during childhood. "The epidemiological evidence [shows there are] increases in asthma and various allergic conditions in children and adults whose environments had significantly reduced pathogen exposure in early life," Pelto told Life's Little Mysteries.

The most common argument against pre-mastication is that infants occasionally catch infectious diseases from the saliva itself. For example, women with HIV are advised against pre-chewing their babies' food. However, research shows that disease transmission through pre-mastication is far less common than was previously assumed, because natural antibodies in saliva significantly reduce the infectiousness of the disease pathogens present there. Research by the immunologist Samuel Baron of the University of Texas Medical Branch has demonstrated that the risk of HIV transmission via saliva is actually very low — lower than the risk of transmission via breast milk.

For example, women with HIV are advised against pre-chewing their babies' food. However, research shows that disease transmission through pre-mastication is far less common than was previously assumed, because natural antibodies in saliva significantly reduce the infectiousness of the disease pathogens present there. Research by the immunologist Samuel Baron of the University of Texas Medical Branch has demonstrated that the risk of HIV transmission via saliva is actually very low — lower than the risk of transmission via breast milk.

Breast-feeding was outmoded in the 1950s, and has since seen a renaissance. Silverstone may simply be ahead of the curve regarding pre-mastication. "The evidence for breast milk is overwhelming," Pelto said. We think the story is identical for both breastfeeding and pre-mastication — they save lives by ensuring good nutrition and good development of the immune system. The evidence for pre-mastication has yet to be completed, but the logic is clear and the epidemiological evidence supports it. "

"

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

How to chew food properly?

Chew well!

Everyone knows that you need to eat calmly, slowly and thoroughly chew your food. But do you know why this is necessary?

But do you know why this is necessary?

It's not just about the aesthetic component. Although it is important, because the sight of a child chewing leisurely is much more pleasant than the sight of a small hasty swallowing large pieces of food. The fact is that thorough chewing of food is also important for the health of the child.

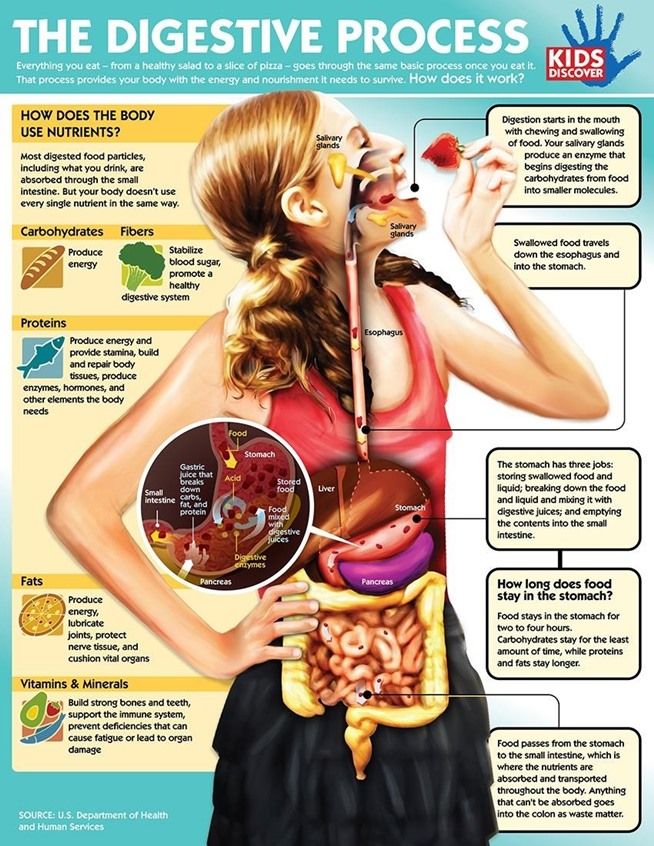

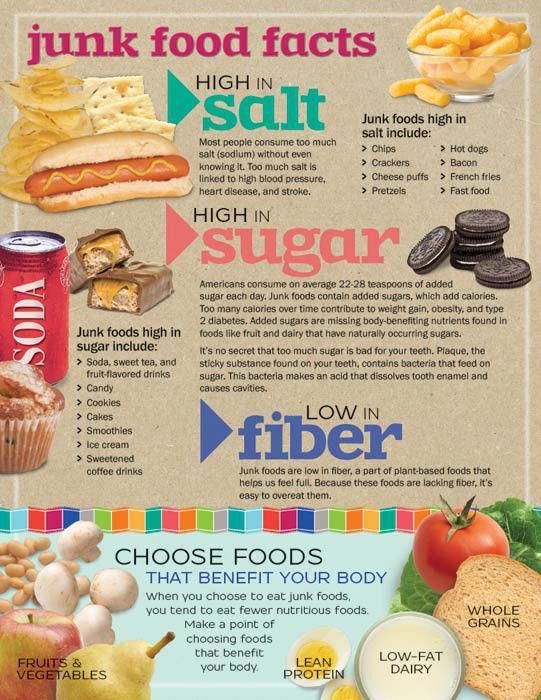

Firstly, the appearance of food, its touch with the receptors of the tongue tunes the body to the digestive process, promotes the production of digestive juices, which means it contributes to better digestion of food.

As already mentioned, the tongue has special taste buds that help us to distinguish all flavors. Swallowing food quickly, the child does not fully feel the taste of food, his taste sensations are depleted. In the oral cavity, cold food is warmed, dry food is moistened, which is of great importance for comfortable digestion.

Important!

A child who chews food badly, in a hurry, swallows air along with food. And this can lead to discomfort, heartburn, abdominal pain, belching and increased gas formation in the intestines.

And this can lead to discomfort, heartburn, abdominal pain, belching and increased gas formation in the intestines.

In the worst case, excessive accumulation of air in the stomach can lead to the backflow of food from the stomach into the esophagus, which, if repeated regularly, can cause inflammation of the esophagus. In addition, with a hurried meal, the likelihood of food getting into the respiratory tract increases. When chewing thoroughly, it is much easier to remove food components that make it difficult to swallow or even dangerous to health. These are fish bones, veins and cartilage.

Digestion of food begins in the mouth. It is wrong to think that this process occurs only in the stomach or intestines. For example, already in the mouth, under the action of saliva enzymes, the process of splitting complex carbohydrates begins. And in the future, in other parts of the digestive tract, well-chopped food is better absorbed and digested faster. Thorough chewing of food develops the muscular apparatus of the face, which has a positive effect on the articulation and facial expressions of the child. That is, we can conclude that a carefully chewing child will speak faster, and his face will be more mobile and expressive.

That is, we can conclude that a carefully chewing child will speak faster, and his face will be more mobile and expressive.

Affects chewing and dental health. The saliva released during chewing forms a protective film on the enamel of the teeth, which is called the pellicle. The alkaline environment of this film prevents the growth of bacteria. In addition, the pressure exerted on the teeth during chewing helps to increase blood flow in the gums, which improves the nutrition of the tissues of the oral cavity and the health of the snow-white teeth of the crumbs.

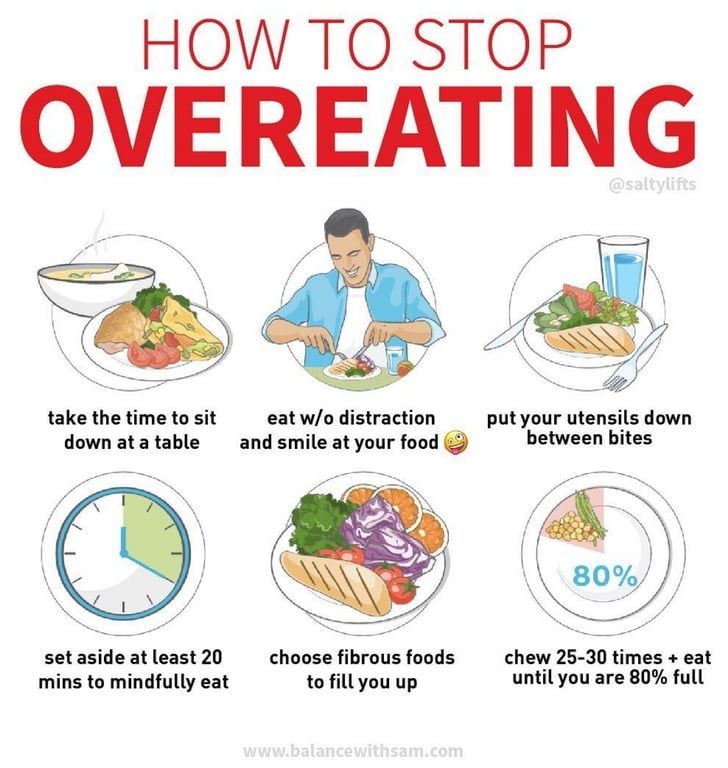

We must not forget that the awareness of saturation lags behind true saturation in time. Therefore, when eating quickly, a child can eat more than he needs. This is especially true for children who are prone to fullness. However, if your baby is small, fast feeding will not save the situation, because poorly chewed food is absorbed much worse.

How much should you chew? Experts advise chewing liquid, semi-liquid and puree food about 10 times, solid food - 30-40 times. To better comply with these conditions, it is recommended not to rush the child while eating, not to divert his attention to something else (TV, phone, computer). Try to be quiet while eating.

To better comply with these conditions, it is recommended not to rush the child while eating, not to divert his attention to something else (TV, phone, computer). Try to be quiet while eating.

How to teach your baby to chew and swallow solid food

The transition from breast milk or formula to adult foods is a gradual and natural process.

The baby can quickly get used to new dishes and diets. However, it also happens that the child refuses to chew or spits out solid food, or even swallows it in pieces. Where are the problems? How to deal with difficulties?

It's time to chew: what is predetermined by nature?

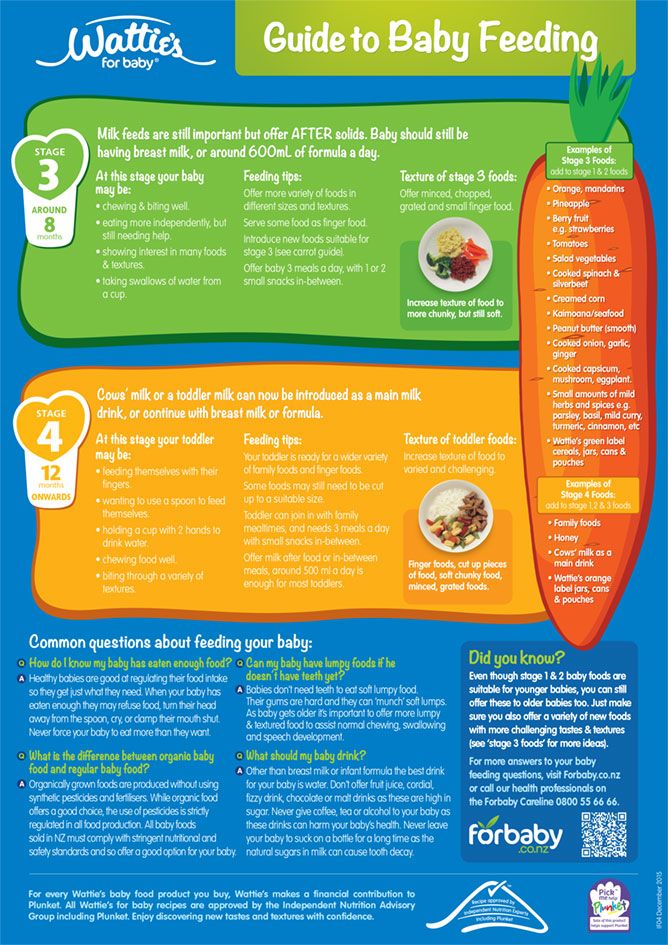

The first chewing movements in a baby appear at about 4–5 months of age. At the same time, the gag reflex begins to move from the middle of the tongue to its posterior third - the pushing movement of the tongue gradually disappears.

By the age of 7-8 months, the baby is usually ready to be introduced to pieces of solid food.

From 7 to 12 months of age, biting and chewing skills are strengthened, and lateral movements of the tongue are developed, moving food to the teeth.

Important!

Don't take the recommended timings lightly. Much depends on the degree of maturity and readiness to learn a new skill: a full-term or premature baby, a healthy child or is sick, teeth have appeared or not yet, the type of feeding.

However, by the age of one year, the baby should be able to chew with his jaws, even if these movements are a little clumsy.

How to teach a child to eat independently: Part 1 and Part 2

Why the child does not want to chew or refuses solid food

There are many reasons: starting with diseases and ending with the laziness of the baby.

Unformed eating habits

Not so long ago, even before the appearance of the first milk teeth, the child received a bagel or cracker from his mother, learning to gradually “chew” unfamiliar solid food with his gums.

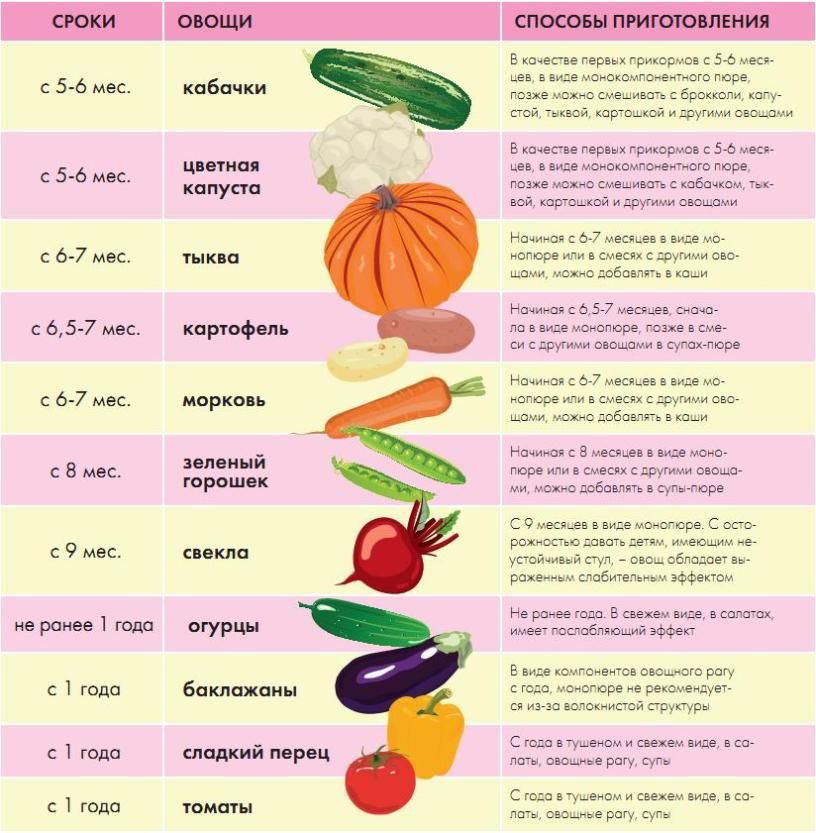

Now, according to WHO recommendations, in addition to the main diet, complementary foods are introduced at the age of 6 months.

Unfortunately, often a baby begins to get acquainted with new products when he already has his first teeth. It seems that it is easier to chew with such helpers. But this is not so. The child uses the teeth for biting, while they interfere with chewing with the gums.

More about complementary foods and pre-nutrition:

We introduce complementary foods. Preparing a baby for first feeding

Feeding. What it is?

Health problems

Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (gastritis, pancreatitis), tonsillitis or pharyngitis, stomatitis and others.

Violation of masticatory muscle tone

The tongue clumsily turns the food, and the muscles do not clench the jaws well. Often the problem occurs after birth trauma.

Early weaning

In order to "get" food from the mother's breast, the baby needs to make an effort - this trains the masticatory muscles. Whereas with a bottle it is quite difficult to develop the tone of these muscles.

Whereas with a bottle it is quite difficult to develop the tone of these muscles.

Incorrect feeding

When a baby eats mashed and/or crushed foods for a long time, he starts to be lazy and does not make any effort to chew.

With a sharp transition from a homogeneous puree to pieces of food, the baby can get nervous and violently resist innovations. From his point of view, there is no “normal” food. Naturally, streams of tears flow and lips squeeze tightly.

However, all these difficulties can be overcome. The main thing is to take your time and be patient.

Everything must be on time: Mom, teach me to chew, I want to eat!

There is no special technique, for everything must go on as usual and gradually.

When to start training?

Approximately at the age of 4-6 months of life - with the appearance of chewing movements and even before the eruption of the first teeth. How not to miss the moment? Invite your child to drink some water from a spoon. When its contents begin to enter the oral cavity, the child is ready to master the chewing skill.

When its contents begin to enter the oral cavity, the child is ready to master the chewing skill.

If the baby continues to eat milk mixtures, breast milk or pureed food, the chewing reflex gradually fades.

Are you against introducing your baby to bagels or livers at the age of 7-8 months? Then it is better to wait for the appearance of most of the teeth and learn to chew with them.

Take your time

Start with small portions. If the child stubbornly refuses a new consistency of complementary foods, do not insist. Please try again after a while.

Solid food or special "trainers"

As long as the baby is small, you can use a rubber teether. Starting around 6-8 months old, gradually introduce your baby to solid foods.

Baby's curiosity is your assistant

When a child tries to lick or “bite off” an apple/cookie with their gums, do not crush these foods. Try to offer him solid food more often - let him train and learn to chew. Be sure to make sure that the baby does not bite off large pieces, otherwise he may choke or choke.

Be sure to make sure that the baby does not bite off large pieces, otherwise he may choke or choke.

Use nibbler - container with twist rim. The device is a container in the form of a mesh or a silicone nozzle with holes. Place pieces of age-appropriate foods inside the container, and then give it to the child’s hands so that he kneads the contents with his gums and at the same time receives nutrition. Do not worry. This method is absolutely safe.

Be consistent and persistent

A blender / grater / meat grinder are convenient helpers for grinding food, but over time, you need to accustom the crumbs to solid food. It is important that the transition be gradual, and the child does not notice a sharp change in the consistency of his usual dishes. Otherwise, he may become capricious or refuse to eat at all.

Decrease the grind time after time: first prepare a smooth puree, then with the inclusion of small pieces, then with thick food containing solid food fragments.

Canned food

When buying, pay attention to the marking. On the recommended nutrition label for 8-10 months of age, look for an indication that the puree contains "pieces that teach you to chew."

Don't distract

Do not turn on cartoons or TV while feeding. If the baby focuses on the process of eating food, then his hands, tongue and lips are better coordinated.

When time is lost: Mom, I don't want to chew!

By about two years of age, a child's eating behavior is mature, so it is difficult to teach him to chew or force him to try an unusual dish.

However, the situation is by no means hopeless, and some of our advice will help you.

Don't keep your baby hungry

The rule does not work well: it's okay, if you get hungry - eat. On the contrary, the baby may get nervous, and all your efforts will go down the drain. In addition, the child often develops a negative attitude towards any innovation in nutrition.

If you started to teach your baby to chew, but he does not eat up during feeding, supplement him with pureed foods.

Do not spare your child

Children aged 1.5–2 years are skillful manipulators. Pretty quickly, they realize that you can whine and get the usual dishes that do not need to be chewed.

Don't hurry

Gradually move from mashed potatoes to thicker foods containing food pieces.

Enlist family support

All must be unanimous and sustained. If you teach a baby to chew, it is not necessary that, for example, a grandmother or aunt, loving and pitying, feed the crumbs with pureed food.

Take the child to be your assistant

Grind food together first in a blender, then with a meat grinder or grater. A little later, offer the crumbs to crush their own food in a plate with a fork. After all, he is already "boooo big"! Usually, over time, the baby begins to get bored with rubbing / crushing, so he gradually begins to chew.

Practice chewing movements

Children like to imitate. Start chewing some goodies with pleasure, for sure, the baby will also want to try it. Of course, you will give it to him, but at the same time show how it should be done correctly.

Of course, the products must be of high quality - for example, marshmallows or chewing marmalade.

Show off your acting skills

Try to "lose" or "break" the blender, mixer, strainer, grater. Say that in case (when it appears in the store) buy everything new. Try not to keep your promise.

Turn learning into an interesting game

From slices of the crumbs' favorite foods on a plate, you can lay out a "rainbow" or "build" a house, "draw" animals.

Add crushed pieces of soft berries and fruits to cereals or purees. Gradually increase the size of the pieces over time.

Expand your diet

Offer a new dish in a non-mashed and not crushed form.