Privatizing poland baby food big business and the remaking of labor

Privatizing Poland by Elizabeth Cullen Dunn - Ebook

Enjoy millions of ebooks, audiobooks, magazines, and more, with a free trial

Only €10,99/month after trial. Cancel anytime.

Ebook325 pages4 hours

Rating: 2 out of 5 stars

2/5

()

About this ebook

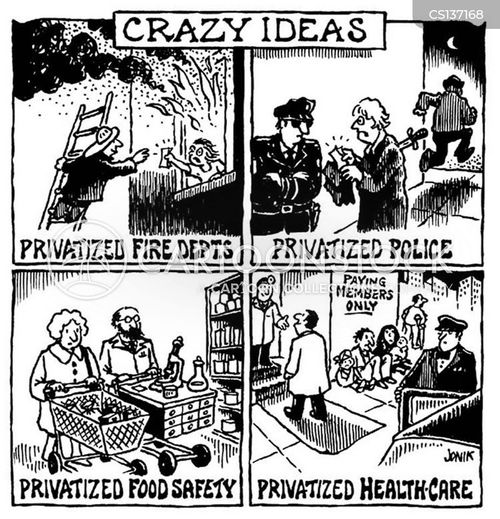

The transition from socialism in Eastern Europe is not an isolated event, but part of a larger shift in world capitalism: the transition from Fordism to flexible (or neoliberal) capitalism. Using a blend of ethnography and economic geography, Elizabeth C. Dunn shows how management technologies like niche marketing, accounting, audit, and standardization make up flexible capitalism's unique form of labor discipline. This new form of management constitutes some workers as self-auditing, self-regulating actors who are disembedded from a social context while defining others as too entwined in social relations and unable to self-manage.

Privatizing Poland examines the effects privatization has on workers' self-concepts; how changes in "personhood" relate to economic and political transitions; and how globalization and foreign capital investment affect Eastern Europe's integration into the world economy. Dunn investigates these topics through a study of workers and changing management techniques at the Alima-Gerber factory in Rzeszów, Poland, formerly a state-owned enterprise, which was privatized by the Gerber Products Company of Fremont, Michigan.

Alima-Gerber instituted rigid quality control, job evaluation, and training methods, and developed sophisticated distribution techniques. The core principle underlying these goals and strategies, the author finds, is the belief that in order to produce goods for a capitalist market, workers for a capitalist enterprise must also be produced. Working side-by-side with Alima-Gerber employees, Dunn saw firsthand how the new techniques attempted to change not only the organization of production, but also the workers' identities. Her seamless, engaging narrative shows how the employees resisted, redefined, and negotiated work processes for themselves.

Skip carousel

Related categories

Skip carousel

Reviews for Privatizing Poland

Rating: 2 out of 5 stars

2/5

3 ratings0 reviews

Book preview

Privatizing Poland - Elizabeth Cullen Dunn

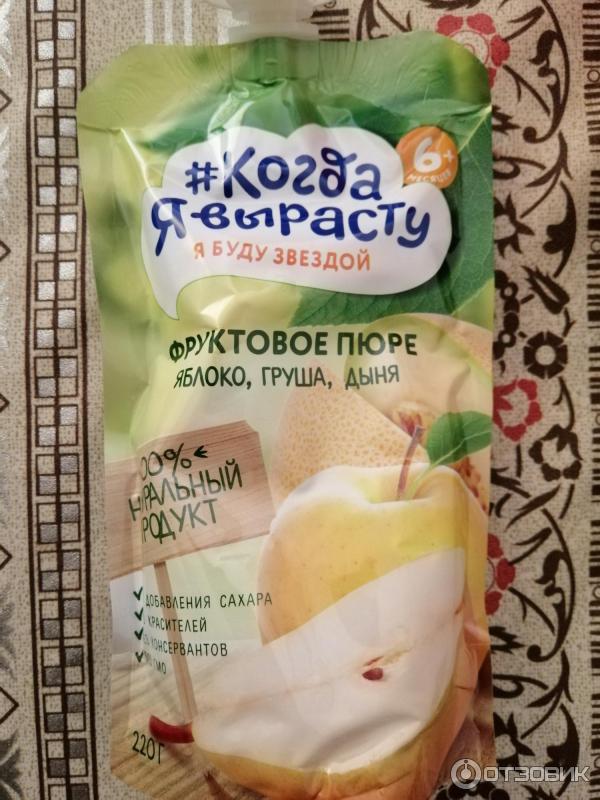

1 The Road to CapitalismGerber Products Company, the baby food company, is headquartered in the tiny town of Fremont, Michigan, population four thousand. It is an hour away by car from the nearest airport, in Grand Rapids. Gerber is a major player—some might say it was the major player—in the jarred baby food industry, which Dan Gerber and the Fremont Canning Company pioneered in 1901. Gerber dominates the U.S. baby food market. Every year, across America, it sells more than four hundred jars of baby food per baby.

It is an hour away by car from the nearest airport, in Grand Rapids. Gerber is a major player—some might say it was the major player—in the jarred baby food industry, which Dan Gerber and the Fremont Canning Company pioneered in 1901. Gerber dominates the U.S. baby food market. Every year, across America, it sells more than four hundred jars of baby food per baby.

Despite its American dominance, declining birthrates and market saturation have forced Gerber to seek markets outside the United States. In 1992, soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of state socialism in Eastern Europe, Gerber bought the Alima Fruit and Vegetable Processing Company of Rzeszów, Poland, and formed the new Alima-Gerber S.A. baby food company. Alima, Gerber officials imagined, could follow the same developmental trajectory that transformed Dan Gerber’s small Fremont Canning Company into the multinational baby care firm, Gerber Products, and reinvigorate the mature parent firm back in Michigan.

Driving from Grand Rapids to Fremont, one easily sees why Gerber officials were struck with the similarity of Alima and Gerber, since their settings look so much the same. Like Rzeszów, Fremont is a fairly small town surrounded by other small towns and villages. The rural landscape is one of rolling hills, fields, and brown scrubby brush punctuated with evergreen trees. The road from Grand Rapids to Fremont is lined with small farmhouses with peeling faded paint, grain silos, and small apple orchards. The names of the streets crossing the two-lane road to Fremont, like Fruit Ridge Road and Peach Ridge Road, refer to the region’s agricultural base. Alongside the road, the signs and the billboards give the area a small-town feel and testify to rural religiosity: Rose of Sharon Market and Garden Center: Say Yes to Jesus,

and T.J.’s Cafe: Happy Birthday Travis

are two of many. In mid-November, old VW buses and pickup trucks pass by with stiff deer carcasses tied to the top or lying in the truck bed.

The road to Rzeszów from Warsaw is much the same. The November climate has the same gray skies and chilly air. The brown scrub, the vegetable fields, and the small villages, one after the other, are like those in Michigan. There are small roadside cafés and small farmhouses with peeling paint similar to those near Fremont. Small shrines punctuating rural roads are marks of everyday religious sentiment, much like the biblical reference in the Rose of Sharon

sign near Fremont. The road to Rzeszów has fewer gas stations and fewer McDonald’s than the road from Grand Rapids to Fremont. Rzeszów has more factories, more people (a population of 250,000), and the occasional horse-drawn wagon to hold up traffic. Nonetheless, the road to Rzeszów feels a lot like the road to Fremont. These are two communities shaped by a common industry, surrounded by apple orchards, and full of small farmers who love the outdoors.

The two factories are also quite similar. Each depends on produce from farms around the plant that is cooked and canned by local people working inside the factory. The most important products in each factory are the same: apples and carrots, the major ingredients for the baby food and juice. Like socialist-era Alima, Gerber was—and, to some extent, still is—a local company with close ties to the surrounding agricultural community. Generations of workers from the same family, both in Fremont and in Rzeszów, have supplied the fruit, vegetables, and labor to make baby food. The two factories appear so similar at first glance that Alima’s own

The most important products in each factory are the same: apples and carrots, the major ingredients for the baby food and juice. Like socialist-era Alima, Gerber was—and, to some extent, still is—a local company with close ties to the surrounding agricultural community. Generations of workers from the same family, both in Fremont and in Rzeszów, have supplied the fruit, vegetables, and labor to make baby food. The two factories appear so similar at first glance that Alima’s own Vademecum,

a compendium of products and methods, uses pictures taken in Michigan to illustrate a text about the Rzeszów operation. Few people at Alima-Gerber have noticed the switch.

Given how similar the two firms and their settings look, it is no wonder that Gerber executives believed they could duplicate their firm’s phenomenal rise, in the new Polish setting. They assumed that Poland was a case of arrested development and that somehow both the firm and the country were developing along the same lines Gerber followed in the early twentieth century. Gerber’s CEO, Al Piergallini, made the comparison explicit:

Gerber’s CEO, Al Piergallini, made the comparison explicit: This country reminds me a lot of the United States in the 1920s

(Perlez 1993). Seeing the firm and the nation as similar also led Gerber executives to assume that Polish rural entrepreneurs, factory workers, and consumers were like the ones they had come to know in Fremont. Since they believed the people were similar and the places were similar (except that Poland was somehow ninety years behind Fremont), Gerber managers believed Alima could follow Gerber’s road to capitalist success.

This, in microcosm, was the same set of assumptions governing the privatization and economic transformation process in Poland at the national level. The designers of postsocialist economic reform believed the people of Poland were essentially the same as people in Western capitalist countries. If only the constraints of communism could be removed, natural tendencies toward capitalist economic rationality, profit maximization, entrepreneurship, work ethics, and consumption patterns would ensure that a market economy would develop spontaneously. According to neoliberal reformers like Leszek Balcerowicz, Poland’s first post-Communist minister of finance and the architect of Poland’s

According to neoliberal reformers like Leszek Balcerowicz, Poland’s first post-Communist minister of finance and the architect of Poland’s shock therapy

plan for economic reform, privatization in all its forms would allow those natural tendencies in persons to be expressed in economic behavior. In the best liberal tradition, the designers of economic reform assumed that the aggregate of these natural human behaviors would create a market economy. As Balcerowicz put it,

A private market economy is the natural state of contemporary society. Indeed, whenever a country lacks private firms, this is due to state restrictions and not due to a lack of potential entrepreneurs. Removing these prohibitions always leads to the development of private enterprise. (Balcerowicz 1995, 133; translation mine)

Balcerowicz and other post-Solidarity neoliberal reformers believed that once fundamentals of capitalism such as private property were established, the Polish economy would resume its place on the path to capitalist development. They assumed that this path was the same one followed by the Western market economies, which Central Europe left in 1945 (and Russia much earlier). According to this ideology, Eastern Europe may have been

They assumed that this path was the same one followed by the Western market economies, which Central Europe left in 1945 (and Russia much earlier). According to this ideology, Eastern Europe may have been backward in time,

but with the advent of privatization, it would be back on the road to a capitalism identical to that found in the West. As economist Janoś Kornai phrased the problem for the whole Eastern European region:

The first road

of capitalist development was abandoned first by the peoples of the Tsarist empire, and later by the other peoples that came under communist-party rule, in favor of a new, second road

that led to the development of the socialist system. Some decades later, it became increasingly plain that socialism in its classical form was a blind alley…. The termination of the sole rule of the Communist Party removes the main road block, so that society can return to the first road, the road of capitalist development. (Kornai 1995, vii–ix; italics in the original)

But Poland is not the United States, and Rzeszów is not Fremont. The apartment blocks, the smokestacks of the town’s airplane engine factory, and the huge concrete monument to the

The apartment blocks, the smokestacks of the town’s airplane engine factory, and the huge concrete monument to the heroes

who helped the Russians invade the city during World War II are all reminders that Rzeszów’s people experienced more than forty years of socialism. While their apple orchards and rural roads may look the same, the two towns were part of systems with vastly different social relationships that gave those orchards and roads widely differing meanings. Rzeszovians and Fremonters might both grind carrots, pack baby food, go to church, and go fishing, but they do not experience the world in the same way. This discovery came as a surprise to Gerber’s managers. As AG’s director of human resources said several years later:

The Americans who bought [Alima] took over its management with the best of intentions, but at the same time, incomplete knowledge of Polish realities, customs, and workers’ attitudes. Not surprisingly, it was hard [for Gerber’s managers] to understand why not all their orders were implemented immediately. (cited in Gestern 1996)

(cited in Gestern 1996)

When Gerber discovered that Alima employees and Rzeszów area farmers were not the same as the people of Fremont, the company began to try to make the people it deals with in Poland into the kind of people it is familiar with. Because Gerber believed Alima was like the Gerber of the 1920s, it applied the same kinds of management techniques to Alima that it had used upon itself in recent decades to transform itself into a new,

global,

and more flexible

corporation. Whether by applying Western management techniques like audit, niche marketing, and standardization to its employees, by reorganizing the relationships between the farmers and the firm and actively changing their farming practices, or by advertising to Polish mothers in order to change the way they feed their babies, Gerber actively sought to reproduce the system of relationships between the firm, its suppliers, and the customers that it had in the United States in the 1990s. In a sense, the underlying assumption of Gerber’s Polish venture, like that of many American companies in Eastern Europe, is that to make the kinds of products it knows, the company first has to make the kinds of people it knows: shop floor workers, managers, salespeople, and consumers like those in the United States.

But why pay attention to the management strategies of a small, not-veryimportant factory in an out-of-the-way Polish town? What do Alima’s experiences have to say about larger, more widespread issues? In the first place, Alima-Gerber’s experiences illuminate much bigger questions about the transformation of state-socialist societies. How does a society carry out massive economic change in such a short time? Alima’s answers to that question—which hinge on the privatization of the firm and transforming the employees who work in it—prefigured some of the central issues surrounding privatization and economic transformation in Poland.

Soon after the big bang

of 1990, it became obvious even to supporters of radical economic liberalization that privatization was a necessary but not sufficient condition for economic restructuring (McDonald 1993; Kozminski 1992; Johnson and Loveman 1995, 32). A culture change

was called for, or so it was thought (Fogel and Etcheverry 1994, 4; Tadikamalla et al. 1994, 216). Some argued that

1994, 216). Some argued that the socialist mentality is basically at odds with the spirit of capitalism

(Sztompka 1992, 19–20; see also Kozminski 1993). While most efforts focused on restructuring both privatized and state-owned enterprises by reeducating managers, employees of all types and consumers were also subjected to more and less subtle forms of reeducation.

To get a Western-style capitalist economy and to participate in ever more rapid flows of capital and goods around the globe, it seemed that new kinds of persons and subjectivities had to be created. In management texts and fashion magazines, in business schools and on shop floors, a variety of methods were employed to promulgate the habits, tastes, and values of postmodern flexible capitalism (Dunn 1996; cf. Harvey 1989).

Alima-Gerber’s attempts to reeducate and reconstruct its managers, employees, and customers thus illustrate one of the most fundamental aspects of the transition

from socialism. They show that the successful creation of a market economy requires changing the very foundations of what it means to be a person. The case of Alima-Gerber highlights how important workplaces are in transforming economies. Firms not only change patterns of production and investment, but also instill new ideas about different kinds of people and what they like, transform notions about what kinds of actions people of different ages, classes, and genders supposedly can do, and change the ways that people regulate their economic behavior.

They show that the successful creation of a market economy requires changing the very foundations of what it means to be a person. The case of Alima-Gerber highlights how important workplaces are in transforming economies. Firms not only change patterns of production and investment, but also instill new ideas about different kinds of people and what they like, transform notions about what kinds of actions people of different ages, classes, and genders supposedly can do, and change the ways that people regulate their economic behavior.

A close study of Alima also shows that the transformation of state socialist societies is not merely a question of changing political parties, building democratic institutions, or even shifting property regimes, as difficult as all those tasks may be. Rather, the transition

is a fundamental change in the nature of power in Eastern Europe. Observing new forms of management and the inculcation of new forms of personhood shows that governmentality in Poland has undergone a sea change in the years since 1989. In this book, I argue that if we define

In this book, I argue that if we define technologies of government

as arrangements of artifacts, practices, techniques, dispositions, and bodies, then the Warsaw Pact countries and the Western market democracies had radically different forms of governmentality between 1945 and 1989. As much as the early architects of socialism might have wished to engage in the same modernizing projects as capitalist powerhouses like the United States, state socialist modernity never operated in the same way as the capitalist modernity of the United States and Western Europe.

The postsocialist transformation is a conscious effort to make the systems of governmentality in the former Soviet Bloc and the capitalist First World

alike—that is, to put Eastern Europe back on the road to capitalism

by making its steering mechanisms the same as those in Western Europe or the United States. Poland’s transformation is not just a transition to ideal-typical capitalism but part of a much larger process of globalization that entails the adoption of many of the same systems of governmentality and regulation used in countries like Germany, the United States, or Japan. Just as in these countries, politicians and managers in Poland are trying to make the leap to a more flexible,

Just as in these countries, politicians and managers in Poland are trying to make the leap to a more flexible, post-Fordist,

or neoliberal form of capitalism. It comes as no surprise, then, to discover that many of the ideas and techniques for transforming people and economies in Poland are based on techniques developed in Japan, Western Europe, and the United States.

Just as in Poland, changes in labor discipline have been a key technology for changing the economies of the First World. Techniques like niche marketing, accounting, audit, and quality control have been used in firms throughout Western Europe and the United States, including at Gerber. These techniques are used to make people into flexible, agile, self-regulating workers who help their firms respond to ever more rapidly changing market conditions. Although popular business writers praise them as liberation management

(Peters 1992), these techniques also have a starkly disciplinary, and often discriminatory, side. They force some workers to work ever harder to comply with the firm’s demands for flexibility, while excluding those they deem inflexible and incapable of self-regulation from working at all (Martin 1994). These doctrines of flexibility—and demands that both workers and firms become

They force some workers to work ever harder to comply with the firm’s demands for flexibility, while excluding those they deem inflexible and incapable of self-regulation from working at all (Martin 1994). These doctrines of flexibility—and demands that both workers and firms become self-regulating selves

—mark the advent of a fundamentally new form of power in postsocialist Eastern Europe.

For many American and Western European workers, it is difficult to critique the new flexible management

or even to criticize the flexible economy

that threatens their job security whenever there is an economic downturn. Fundamental tenets about what it means to be a person—an individual, accountable,

responsible, self-managing person—mean that many workers blame themselves, not their firms or the national economy, when they are unhappy about discipline at work or when they become unemployed (Newman 1999). Polish workers, however, have a stronger standpoint from which to criticize these changes in management and in personhood, because the shift in governmentality is not total. Polish workers spent more than forty years under socialism, which organized both production and personhood in very different ways. While Poles accept many of the changes that global capitalism brings—and eagerly welcome some of them—their historical experience of socialism and the cultural system built and sustained in those decades also allow them to contest, modify, and reinterpret many initiatives of multinational corporations. Certainly, their sense of themselves as persons has been drastically altered by their contact with the ongoing dramatic changes in world capitalism. However, their history, religious background, concepts of gender and kinship, and ideas about social relationships all ensure that their sense of themselves as parts of a capitalist system is not the same as that found in the United States.

Polish workers spent more than forty years under socialism, which organized both production and personhood in very different ways. While Poles accept many of the changes that global capitalism brings—and eagerly welcome some of them—their historical experience of socialism and the cultural system built and sustained in those decades also allow them to contest, modify, and reinterpret many initiatives of multinational corporations. Certainly, their sense of themselves as persons has been drastically altered by their contact with the ongoing dramatic changes in world capitalism. However, their history, religious background, concepts of gender and kinship, and ideas about social relationships all ensure that their sense of themselves as parts of a capitalist system is not the same as that found in the United States.

How, then, do Polish workers respond to attempts to make them into the new, flexible

workers of late capitalism? How do Polish workers, managers, and consumers contest and rework the categories of persons imported by American management, and how might those contestations form the basis of a critique of contemporary capitalism? Do their attempts to block, modify, and circumvent new managerial technologies change the system of relations emerging in Poland into a distinct form of capitalist economy? Do struggles and negotiations on the shop floor turn the disciplinary power of flexible accumulation into something new and unrecognizable, just as they warped and weakened socialist authoritarian power?

In this book I explore how Polish workers use experiences of socialism and Solidarity union activism, as well as Catholic, kin, and gender ideologies, to redefine themselves and negotiate work processes and relationships within the firm. By deploying alternate concepts of value, Solidarity’s expectations of the relationship between worker and enterprise, and webs of acquaintanceship developed in the shortage economy, workers seek to develop other subjectivities and to become subordinated in a way they can live with. Their struggles offer a new lens through which to see the ways that power is distributed inside the

By deploying alternate concepts of value, Solidarity’s expectations of the relationship between worker and enterprise, and webs of acquaintanceship developed in the shortage economy, workers seek to develop other subjectivities and to become subordinated in a way they can live with. Their struggles offer a new lens through which to see the ways that power is distributed inside the flexible

firms of the new global economy and which kinds of people are excluded from it. They frame changes in political economy as changes in the moral economy of work. Hence the challenges workers face open up an opportunity to critically examine changes in the lived experience of global capitalism as well as the more narrowly defined transition

in Eastern Europe.

Alima in Global Context, or, Why Rzeszów and Fremont Are Nowhere Near the Same Place

In an article entitled Gridded Lives: Why Kazakhstan and Montana Are Nearly the Same Place,

Kate Brown looks out over the streets of both Karaganda and Billings. She argues that

She argues that by straining away the mountains of verbiage produced during the Cold War, we may find the Soviet Union and the United States share a great deal in common

(2001, 21–22). In a courageous move, Brown asks how these places, once set up as polar opposites, might be alike. She wants to reveal how power was produced in both places through forms of Foucauldian discipline and to show how both capitalist and socialist spaces were artifacts of a common modernity. By examining how managers of large enterprises in both places sought to ensure the regimentation and subjection of labor,

she hopes to show how they created corresponding patterns of subjection

(2001, 23).

But was work really organized in the same way in both capitalist and socialist enterprises from the early 1920s, when the Soviets first began to create socialist industrial society, until 1989? Did state socialism’s factories and collective farms produce the same kinds of subjectivities that American manufacturing plants and corporate farms did? Were there so few differences between working in Billings and Karaganda or Fremont and Rzeszów? The stakes in answering these questions go beyond a theoretical debate about whether capitalism and socialism were merely variations on a theme (although that has been a steady argument in the literature on work—see Braverman 1974; Van Atta 1986; Burawoy and Lukács 1992). Rather, the questions go right to the core of the postsocialist transformation project. Like Brown, Poland’s early neoliberal reformers and privatizing managers also assumed that capitalist and socialist factories organized work in similar ways. But if they were incorrect, the map they drew of the road to capitalism was, from its very inception, flawed.

Rather, the questions go right to the core of the postsocialist transformation project. Like Brown, Poland’s early neoliberal reformers and privatizing managers also assumed that capitalist and socialist factories organized work in similar ways. But if they were incorrect, the map they drew of the road to capitalism was, from its very inception, flawed.

The idea that Eastern European socialism and American capitalism shared specific ways of organizing industrial work comes from a peculiar historical conjuncture. Ironically, given that the early Soviets were trying to create a society antithetical to capitalism, it was the innovations of Henry Ford, a pathbreaking American capitalist, which inspired early models of Soviet production systems. Planners argued that the utopian values of efficiency, rationality, and industrialization would lift Russia out of backwardness, and they grouped those values under buzzwords like Amerikanizatsiya (Americanization). Fordizatsiya became a metaphor for the speedy industrial tempo, high growth, and productiveness that characterized the Soviets’ ideal modernity (Stites 1989, 149). Ford’s memoir, My Life, appeared in eight translated editions in the USSR in the 1920s, and peasants went so far as to name both their tractors and their children after Henry Ford (Stites 1989, 148).

Ford’s memoir, My Life, appeared in eight translated editions in the USSR in the 1920s, and peasants went so far as to name both their tractors and their children after Henry Ford (Stites 1989, 148).

The cult of Henry Ford that emerged in 1920s Russia went beyond metaphor and imagery. Ford not only shaped the Soviet imagination, but he also exercised a profound influence on the organization of state socialist industry. Between 1920 and 1926, the Soviet regime ordered more than twenty-four thousand Fordson tractors, as well as Ford motorcars (Stites 1989, 148). Fascinated by the technology, both Lenin and Stalin became great admirers of Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant in Michigan, which at that time was the largest industrial enterprise in the world. Seeking to emulate the assembly line, which he saw as the centerpiece of capitalist economic power, Stalin invited Henry Ford himself to design the Gorkovskiy Automotive Plant and arranged for American engineers and skilled American workers to train the Soviets in the proper administration of production (Dyakanov 2002).

The huge, vertically integrated enterprise, along with the gridded cities and large industrialized farms that Brown (2001, 38) describes, became the centerpiece of the Fordist vision of modernity. Vertical integration was already in wide use in the United States by the 1950s—including at Gerber’s Fremont plant—when the newly socialist states of Eastern Europe began replicating it at the end of World War II. Socialist planners hoped to spur development by using vertical integration to achieve economies of scale. In the early 1960s, Polish planners began reorganizing the Alima factory along Fordist lines as part of a plan to rationalize the food system. Although Alima had been built as a candy and jam factory before World War II, socialist planners in the 1960s ordered Alima to specialize in the production of a standardized range of baby foods. Although fruit and vegetable production had to be geographically dispersed in order to be close to producers, rather than being spatially concentrated like Ford’s River Rouge plant, Alima became a part of a socialist corporation known as Zjednoczenie Przemyslu Owocowo-Warzywnego (ZPOW, the United Fruit and Vegetable Industries), which was run directly by the Ministry of Food and Agricultural Industries as if it were one vast, vertically integrated enterprise. With vertical integration and with assembly-line technology imported from Western Europe, socialist Alima modeled itself on the basic Fordist model as much as capitalist Gerber did.

With vertical integration and with assembly-line technology imported from Western Europe, socialist Alima modeled itself on the basic Fordist model as much as capitalist Gerber did.

Large enterprises organized along Ford’s assembly-line model—whether state socialist or capitalist—demanded a distinctive form of labor discipline. In the United States, Ford’s River Rouge plant and Gerber’s Fremont Canning Company, like other enterprises of the 1920s, used a form of discipline known as Scientific Management

and organized their shop floors along the lines sketched out by efficiency expert Frederick Winslow Taylor.¹ Fordist firms used Taylor’s methods to separate mental and manual labor, to wrest control of the production process out of the hands of skilled craftsmen and to centralize control of the production process in the hands of managers. Managers using the Taylor method applied engineering principles to workers to improve their efficiency. Since Ford’s assembly line had already broken the production process down into simple, repetitive jobs that each worker did over and over, Taylorist industrial engineers focused on breaking those jobs down even further. They hovered over workers with stopwatches, timing each worker’s tiniest movements, and then tried to recombine those movements in ways that would to increase the amount of output per shift. The Taylor system aimed at making workers into parts of the machines they controlled: passive objects performing the same motion over and over, in a rhythmic and efficient fashion. To spur workers to produce more and to goad them into accepting the dictates of the industrial engineers, Fordist firms paid employees on the shop floor by the piece rather than by the hour. The result of this system was a radical deskilling of industrial work—and the advent of a uniquely mind-numbing and backbreaking form of labor (Taylor 1947; Aglietta 1987, 113–16; Hirsch 1984, 15–16; Aitken 1960, 13–48; Brenner and Glick 1991, 76).

They hovered over workers with stopwatches, timing each worker’s tiniest movements, and then tried to recombine those movements in ways that would to increase the amount of output per shift. The Taylor system aimed at making workers into parts of the machines they controlled: passive objects performing the same motion over and over, in a rhythmic and efficient fashion. To spur workers to produce more and to goad them into accepting the dictates of the industrial engineers, Fordist firms paid employees on the shop floor by the piece rather than by the hour. The result of this system was a radical deskilling of industrial work—and the advent of a uniquely mind-numbing and backbreaking form of labor (Taylor 1947; Aglietta 1987, 113–16; Hirsch 1984, 15–16; Aitken 1960, 13–48; Brenner and Glick 1991, 76).

Fig. 1. Advertising for Bobo Frut brand juices, circa 1979. The label and the logo remained virtually unchanged until after Gerber acquired Alima (formerly ZPOW) in 1992.

Workers in Taylorized plants often rose up against the system, demanding that managers put away their stopwatches and give workers back their abilities to decide how best to accomplish their tasks. The Taylor system of labor discipline was never implemented in its entirety anywhere in the United States (Aitken 1960; Van Atta 1986, 330). However, elements of scientific management found their ways into Fordist factories in the United States and around the world, where they shaped factory life for decades. In an Oregon fish-canning factory in the early 1970s, Barbara Garson observed factory managers watching women gut salmon and using the bones from the picked-over fish, rather than stopwatches, to determine the women’s rate of work (Garson 1975).

The Taylor system of labor discipline was never implemented in its entirety anywhere in the United States (Aitken 1960; Van Atta 1986, 330). However, elements of scientific management found their ways into Fordist factories in the United States and around the world, where they shaped factory life for decades. In an Oregon fish-canning factory in the early 1970s, Barbara Garson observed factory managers watching women gut salmon and using the bones from the picked-over fish, rather than stopwatches, to determine the women’s rate of work (Garson 1975).

Enjoying the preview?

Page 1 of 1

Privatizing Poland by Elizabeth Cullen Dunn | Paperback

Skip content

{{/if}} {{#if item.templateVars.googlePreviewUrl }} Google Preview {{/if}}

{{#if item. imprint.name }}

imprint.name }}

Imprint

{{ item.imprint.name }}

{{/if}}

{{#if item.title}}

{{/if}} {{#if item.subtitle}}

{{/if}} {{#if item.templateVars.contributorList}} {{#if item.edition}}

{{{ item.edition }}}

{{/if}}

{{#each item.templateVars.contributorList}}

{{{this}}}

{{/each}}

{{/if}}

{{#if item. templateVars.formatsDropdown}}

templateVars.formatsDropdown}}

Format

{{/if}}

{{#if item.templateVars.formatsDropdown}} {{{item.templateVars.formatsDropdown}}} {{/if}} {{#if item.templateVars.buyLink }} {{ item.templateVars.buyLinkLabel }} {{/if}} {{#if item.templateVars.oaISBN }}

Open Access

{{/if}}

This work can be downloaded for non-commercial purposes:

{{item. title}} is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

title}} is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

{{#if item.description}}

{{{ item.description }}}

{{/if}}

- media {{#if item.templateVars.reviews}}

- praise {{/if}} {{#if item.templateVars.contributorBiosCheck}}

- Author {{/if}}

- for educators {{#if item.templateVars.moreInfo}}

- more info {{/if}} {{#if item.

- awards {{/if}}

templateVars.awards}}

templateVars.awards}} - {{#if item.templateVars.reviews}}

- {{#each item.templateVars.reviews}} {{#if this.text}}

{{#if this.text}} {{{this.text}}} {{/if}}

{{/if}} {{/each}} {{/if}} {{#if item.templateVars.contributorBiosCheck}} - {{#if item.templateVars.authorBios}}

{{#if item.templateVars.contributorImageCheck}}

{{#each item.templateVars.authorBios}} {{#if this.

image}} {{/if}} {{/each}}

image}} {{/if}} {{/each}} {{/if}}

{{#each item.templateVars.authorBios}} {{#if this.bio}} {{{this.bio}}} See all books by this author {{/if}} {{/each}}

{{/if}} {{/if}} - Request an Exam or Desk Copy {{#if item.templateVars.contentTab}}

Contents

{{{ item.templateVars.contentTab }}} {{/if}} - {{#if item.templateVars.moreInfo}} {{#each item.templateVars.moreInfo}}

{{{ this }}}

{{/each}} {{/if}} {{#if item. - {{#each item.awards}}

{{ this.award.name }}

{{#if this.position}}( {{ this.position }} )

{{/if}} {{/each}} {{/if}}

awards}}

awards}} Also of Interest

Book Finder

404 Page not found

- About the Academy

- Information about the educational organization

- Basic information

- Structure and governing bodies of an educational organization

- Documents

- Education

- Educational standards and requirements

- Manual. Pedagogical (scientific and pedagogical) staff

- Logistics and equipment of the educational process

- Scholarships and student support measures

- Paid educational services

- Financial and economic activities

- Vacancies for admission (transfer) of students

- Available environment

- International cooperation

- Rector

- Structure (faculties, departments, departments)

- History

- Charter

- Library

- License and certificate of state accreditation

- Educational conditions for disabled people and persons with disabilities

- Vacancies

- Contacts

- Antiterror

- Anti-corruption

- Professional retraining

Today "Omsk Humanitarian Academy" is a multidisciplinary complex, which includes an information and computer center, a scientific library, a publishing house, a center for promoting employment, a faculty of additional education, a center for distance education, postgraduate studies.

- Home

Today "Omsk Academy for the Humanities" is a multidisciplinary complex, which includes an information and computer center, a scientific library, a publishing house, a center for promoting employment, a faculty of additional education, a center for distance education, and postgraduate studies.

- Legal documents

- News

- Professional retraining

- Refresher courses

- Application forms

- Internship

- Business training

- Home

- Information about the educational organization

- Applicants

- All about admission

- Admission Committee

- Admission Committee

- Cost of 1 course for the 2022/2023 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for the 2021/2022 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for 2020/2021 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for the 2019/2020 academic year

- Admissions Committee

- Documents and references

- Cost of 1 course for the 2022/2023 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for the 2021/2022 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for 2020/2021 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for the 2019/2020 academic year

- Samples of issued documents

- Educational conditions for the disabled and persons with disabilities

- Preparatory courses

- Responses to requests related to admission to training

- Educational conditions for the disabled and persons with disabilities

- Online Document Submission Service

- Admissions Committee

- Online Document Submission Service

- Cost of 1 course for 2020/2021 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for the 2019/2020 academic year

- Samples of issued documents

- Educational conditions for the disabled and persons with disabilities

- Preparatory courses

- Responses to requests related to admission to training

- Preparatory courses

- Admissions office

- Documents and references

- Cost of 1 course for 2020/2021 academic year

- Cost of 1 course for 2019/2020 academic year

- Samples of issued documents

- Educational conditions for the disabled and persons with disabilities

- Preparatory courses

- Responses to requests related to admission to training

- Samples of issued documents

- Responses to requests related to admission to training

- Online Document Submission Service

- Bachelor / Master

- Admission campaign 2022

- Basic information

- Directions of training

- Entrance examinations

- Number of places for admission to study

- Number of applications submitted

- Lists of applicants

- Enrollment details

- Admission campaign 2022

- PhD

- Admission campaign 2022

- How the learning process looks like in the personal account of a student of the Omsk Humanitarian Academy

- Photo tour

- Students

- Electronic information and educational environment

- Faculties and departments

- Tuition fees

- Library

- Links

- Bulletin Board

- Schedule

- Alumni

- Career Center

- Professional retraining and advanced training

Today, the Omsk Academy for the Humanities is a multidisciplinary complex, which includes an information and computer center, a scientific library, a publishing house, a center for promoting employment, a faculty of additional education, a distance education center, and postgraduate studies.