Solid foods for babies with reflux

Feeding A Baby With Reflux | Parenting Blog | Babocush Limited

It may seem like it was just yesterday when you brought home your little bundle of joy then just like that, it’s time to wean your baby off of milk and introduce solid foods. This process might feel overwhelming, especially if your child is still experiencing baby reflux.

What are the symptoms of baby reflux?

It is important to note the symptoms. Repeated crying, vomiting or spitting up, arching of the back or neck during or after feeds, recurrent ear infections, incapacity to sleep or frequent waking, irritability and lastly, frequent hiccups. Babies typically grow out of reflux within the first two years of their life. With that being said, there are still some foods that can aggravate reflux and others that can ease it.

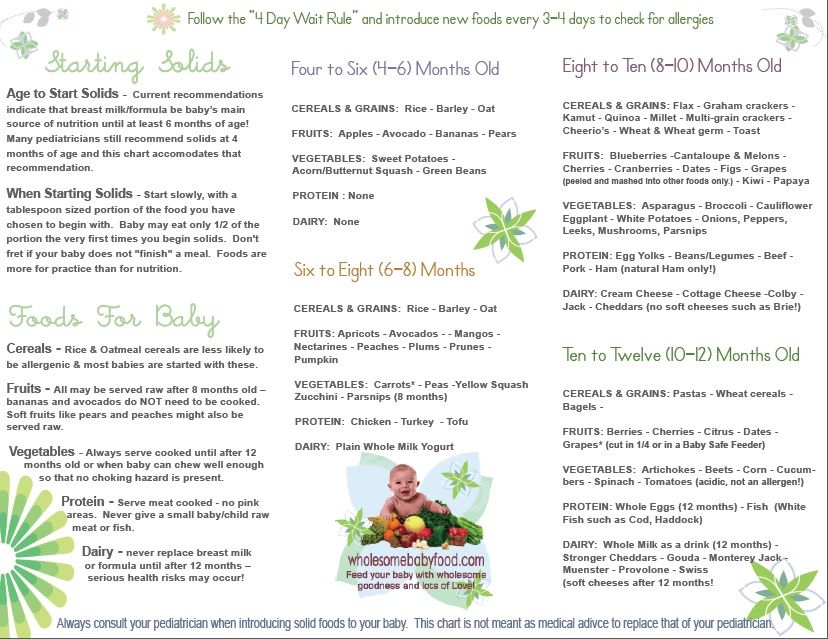

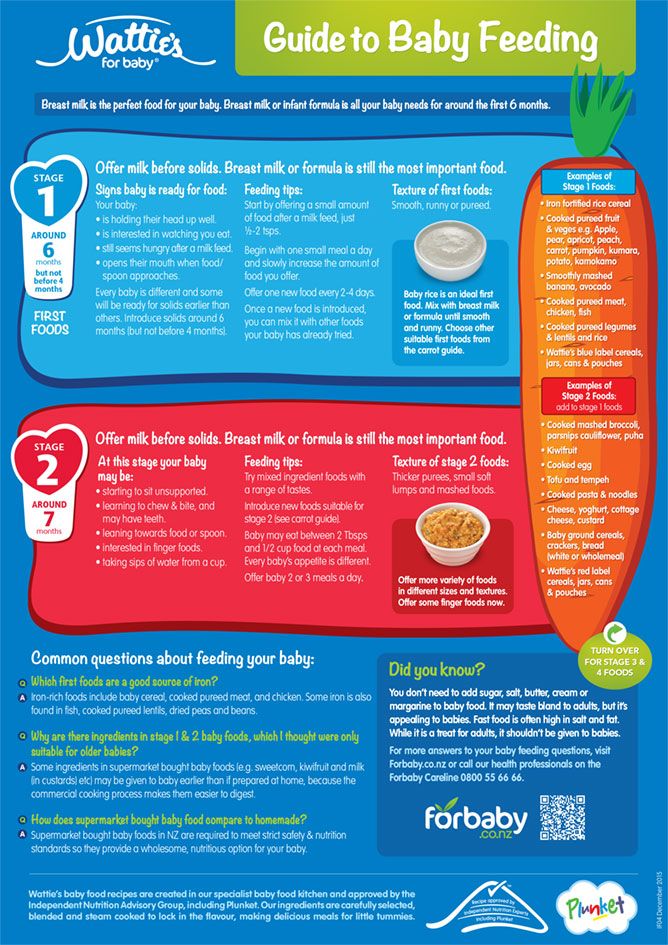

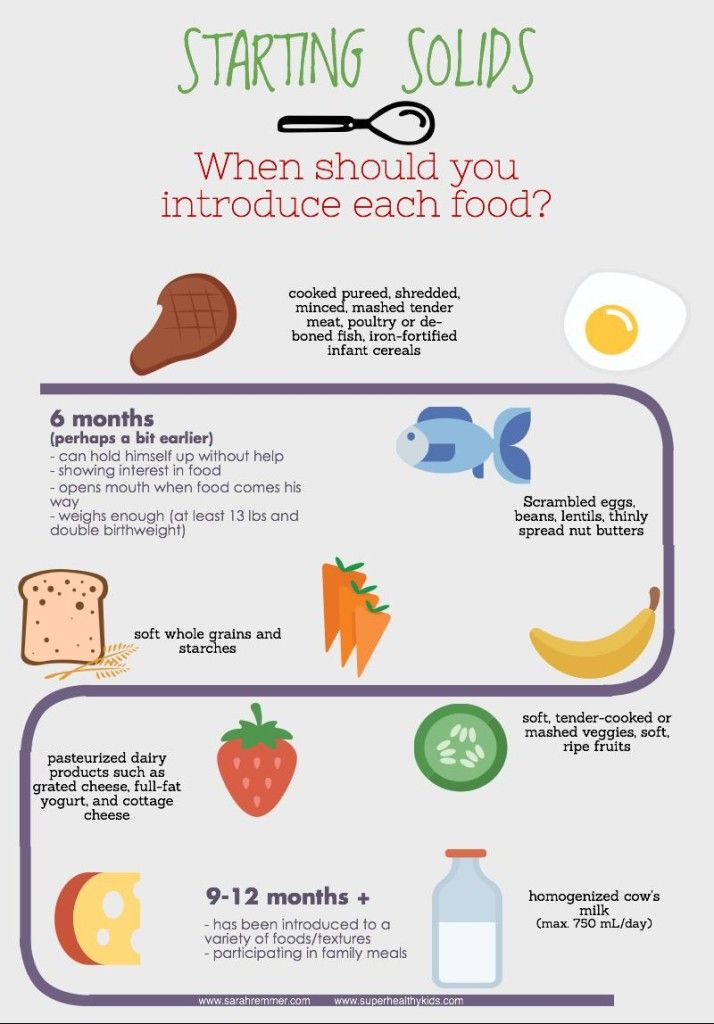

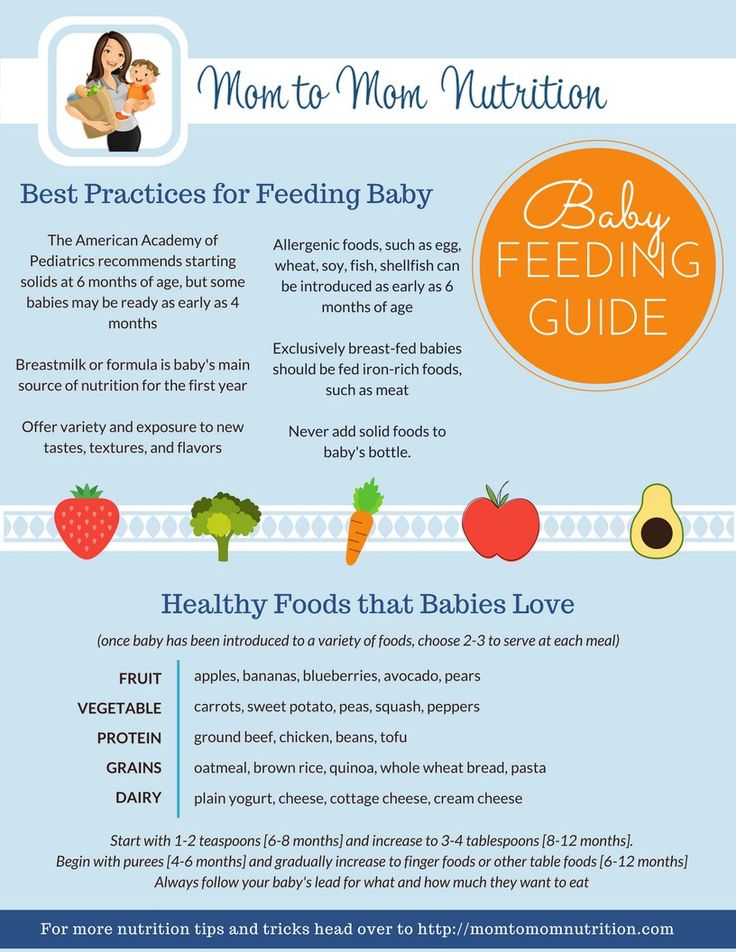

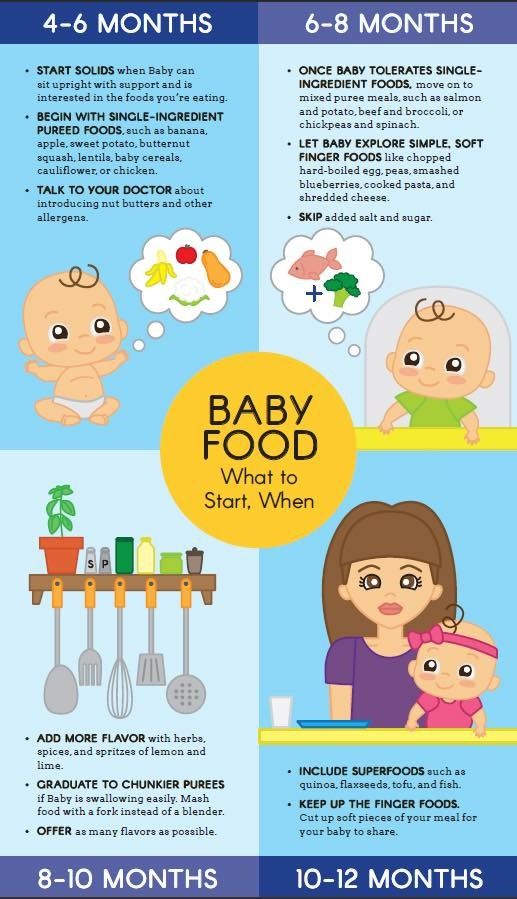

If your baby suffers with reflux, you may feel more comfortable consulting your doctor before you wean your baby off milk and transition them onto solid foods. As a general rule of thumb, you should avoid giving your baby solid food before they’re four months old.

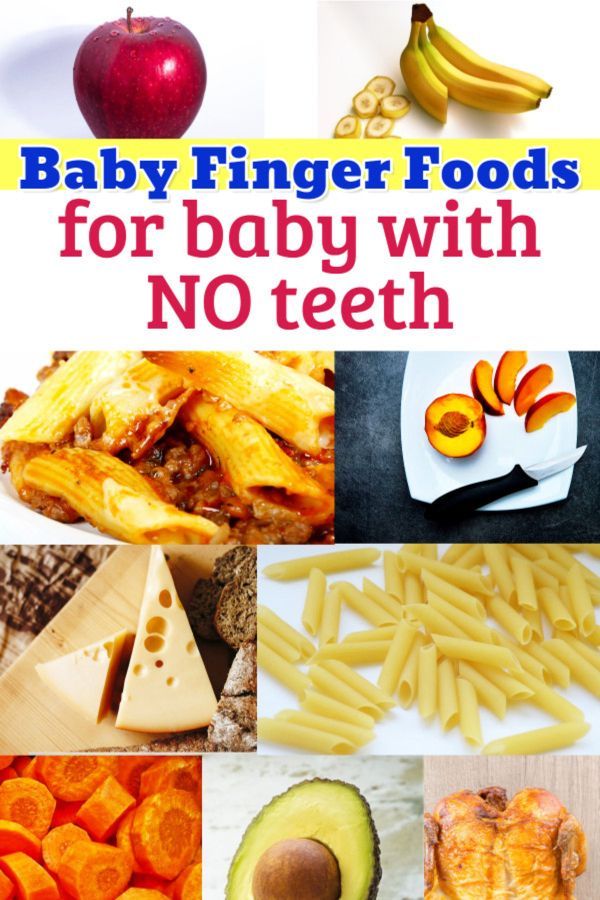

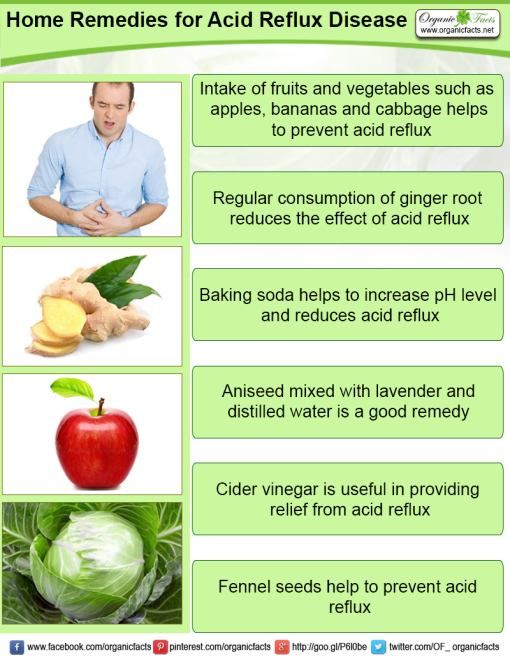

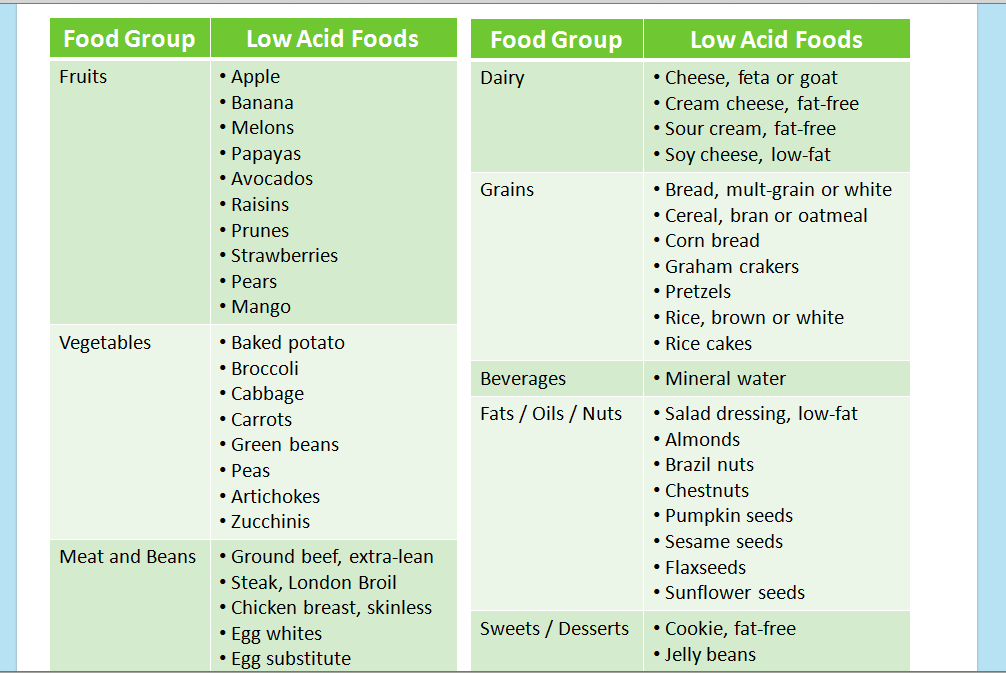

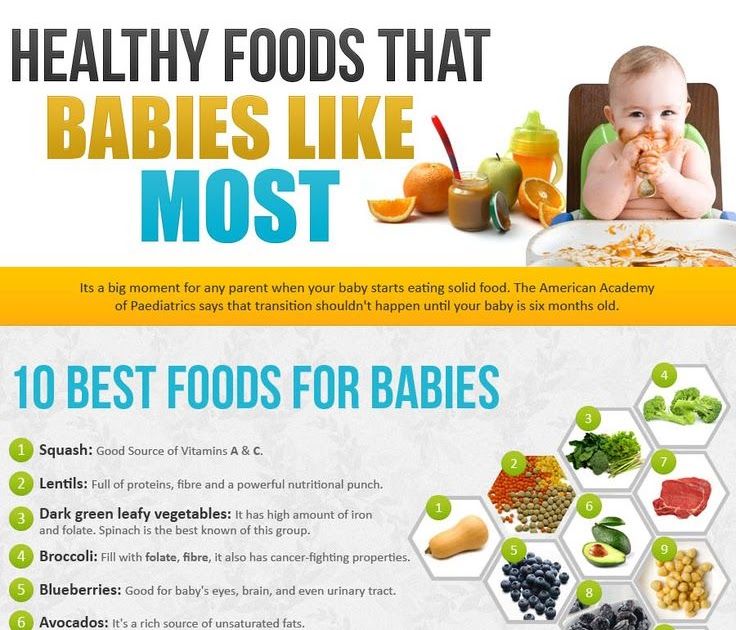

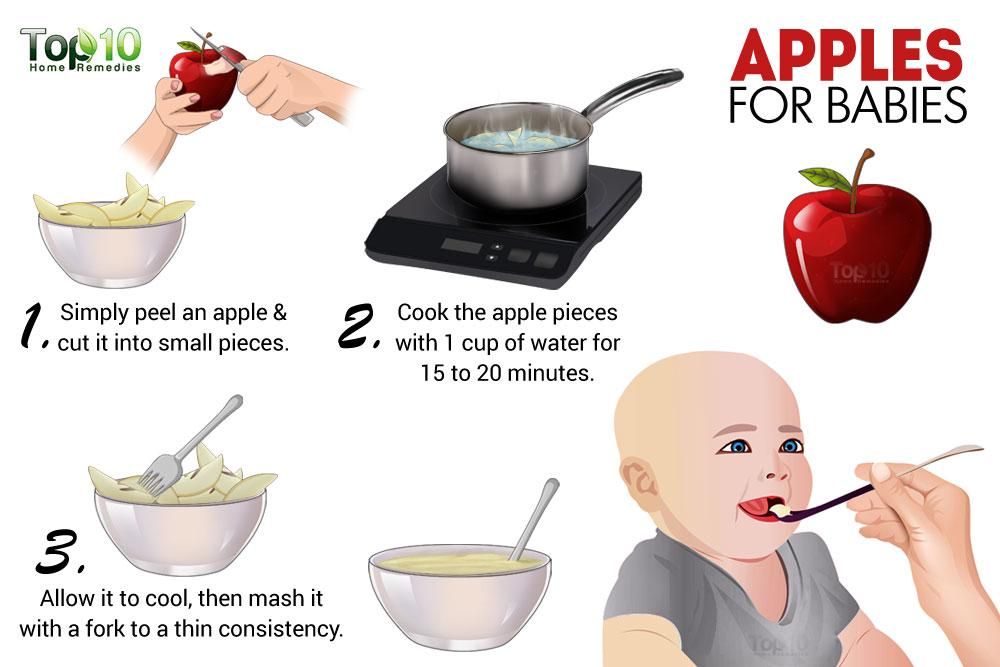

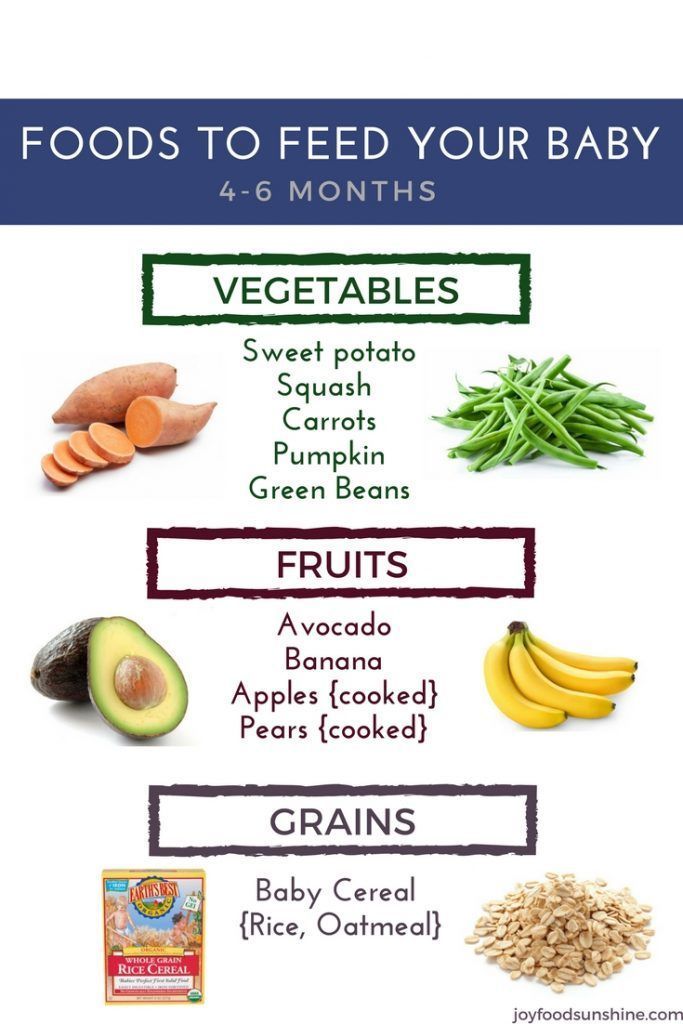

It’s important that you start the weaning process with purees and baby led weaning.The best foods to feed a baby with reflux are purees of vegetables, particularly root vegetables like potatoes, carrots, pumpkin, swede, parsnips and sweet potato. You can also feed your baby any non-acidic fruits. You should avoid citrus fruits like oranges, apples and grapes, tomatoes, peppers, courgettes, cucumbers and aubergines. In addition to that, you should also avoid any foods that have cow’s milk proteins as well as spicy foods.

How to introduce solid foods?

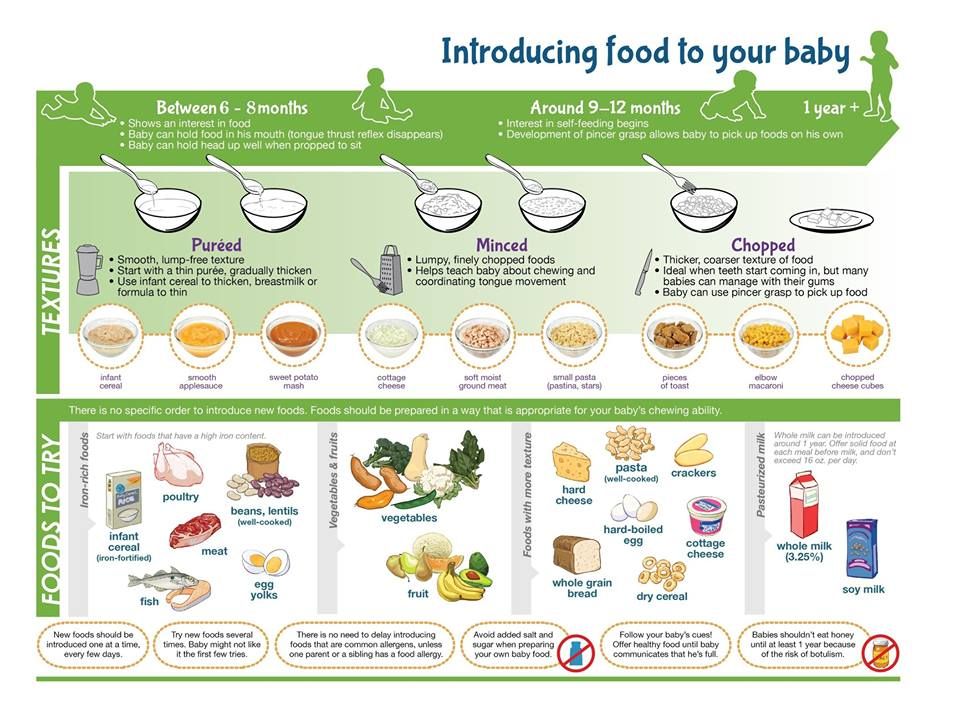

By the time your little one is 4 to 6 months old, you'll probably have your breastfeeding or formula drill down to an art. However, don’t get too comfortable - your baby will soon be ready for "real" food. When it comes to giving your baby solid food, there are a few tips you can follow that can make the process much easier…

Wean your baby slowly

As a general rule of thumb, you should wean your baby slowly and let them take the lead on how much food they need. Don’t hurry meal times, allowing plenty of time for food to settle in your baby’s tummy.

Don’t hurry meal times, allowing plenty of time for food to settle in your baby’s tummy.

Start with smooth foods

You should also start your baby on food that is completely smooth. The textures of different kinds of foods can be a trigger for your infant to spit it up. That is not to say you can never introduce different textures, just make sure that you do so slowly. You should also make sure that you sit your baby upright when feeding them.

Watch out for allergies

You can include any foods that are a part of your family’s diet during complementary feeding. As a precaution, you could introduce foods one at a time for three days at first and, if your baby has no issues, the next new food should be added.

This way, any problematic food would be easier to recognise in the unlikely event that an acute or delayed form of allergic reaction occurs. Once potential allergens, such as eggs and peanuts, have been introduced it is recommended that you continue to include them in your baby’s diet, ideally at least twice a week, to ensure that your baby remains tolerant to that particular food.

Spacing the time in between introducing new foods will give you the opportunity to discover the foods your baby likes and dislikes. Although your baby’s reflux can make introducing solid foods a challenge, it’s by no means impossible.

Related Blogs:

- Why Do Babies Hiccup?

- How To Burp A Baby

Solid Foods To Help with Infant Reflux in Babies

Introducing solid foods to your baby can seem like a daunting challenge, but with some helpful guidance this task will be a lot easier—especially for those babies that struggle with infant reflux or Infant Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (Pediatric GERD).

Currently, medical research indicates that roughly fifty percent of babies are born with some degree of infant reflux. Sadly, in many cases infant reflux is misdiagnosed as colic and as a result many months may pass without the simple diet modifications that will make your baby healthier and more comfortable.

Below are the symptoms of infant reflux that you should be aware of:

- frequent crying

- vomiting or spitting up

- arching of the back or neck during or after feeds

- frequent ear infections

- inability to sleep or frequent waking

- irritability

- frequent hiccups

A vast majority of children will grow out of infant reflux around age two. In fact a lot of parents and professionals notice positive changes when solid foods are finally introduced.

In fact a lot of parents and professionals notice positive changes when solid foods are finally introduced.

What Solid Foods are Good for Babies with Infant Reflux?

Having a comprehensive list of the solid foods that babies with reflux tolerate well would be a wonderful tool to have—unfortunately the reality is that every baby is different. How one baby reacts to certain foods will be different than another. But there are mainstay solid foods that can help infant reflux.

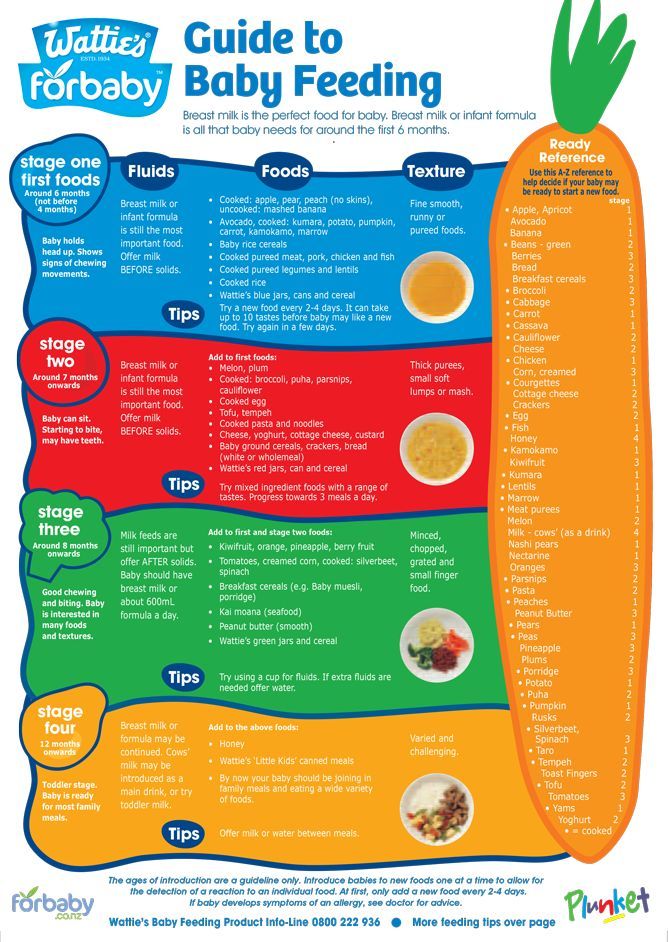

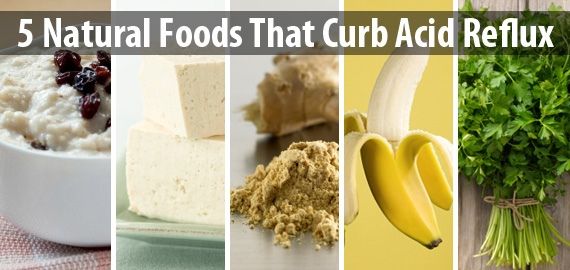

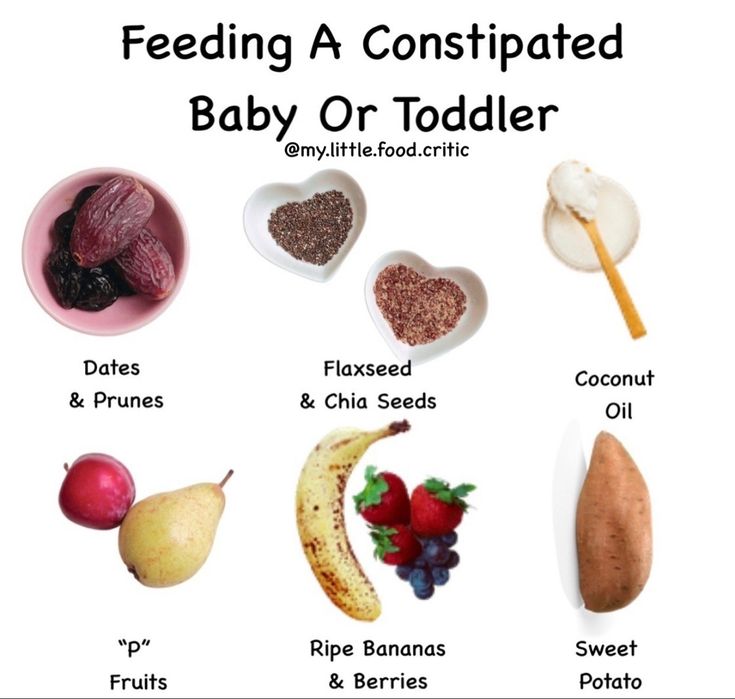

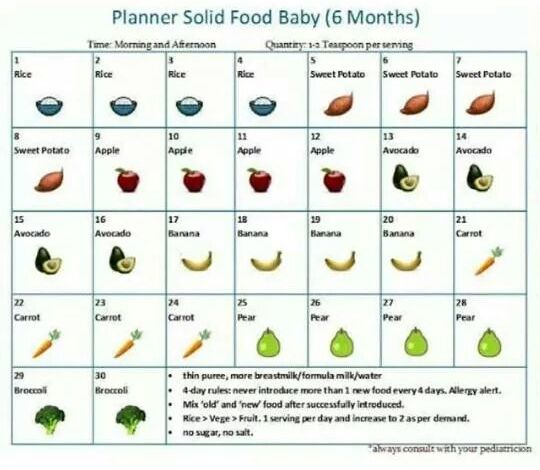

With your doctor’s permission, you can try introducing oatmeal instead of rice cereal or even pureed vegetables. For some babies with reflux, rice cereal contributes to excessive gas and even constipation.

On the fruit side, avocados, pears, and bananas tend to be good first foods for babies with reflux. All aid in digestion, are low in acidity, and provide great nutrients.

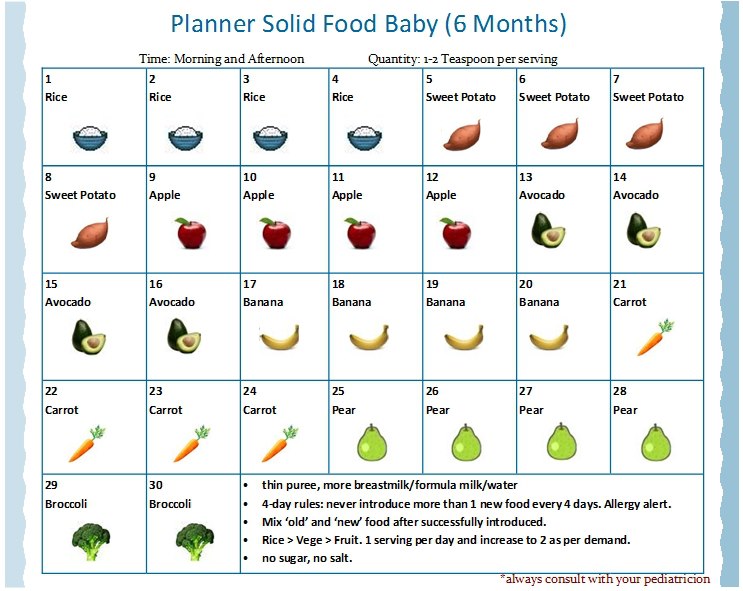

In ordinary cases, doctors recommend starting a baby on solid foods around six months of age. The pattern generally is as follows, first cereal, then vegetable, and lastly fruit.

The pattern generally is as follows, first cereal, then vegetable, and lastly fruit.

However, in the case of infant reflux a growing number of medical professionals recommend using cereal to thicken the formula or breastmilk before they are six months old to help keep down the milk.

While there is not a large amount of medical data that backs up the assertion that this method works, a number of doctors prefer parents try this trick before prescribing medication.

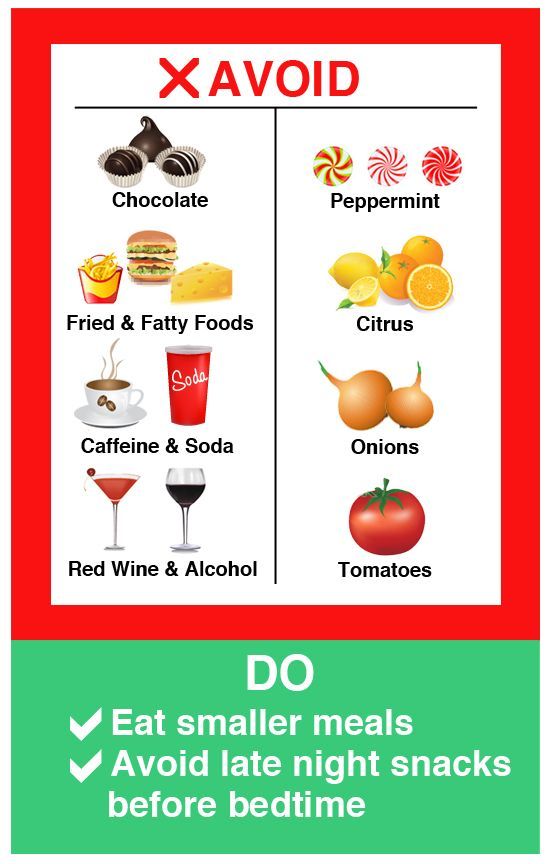

What Foods Make Infant Reflux Worse?

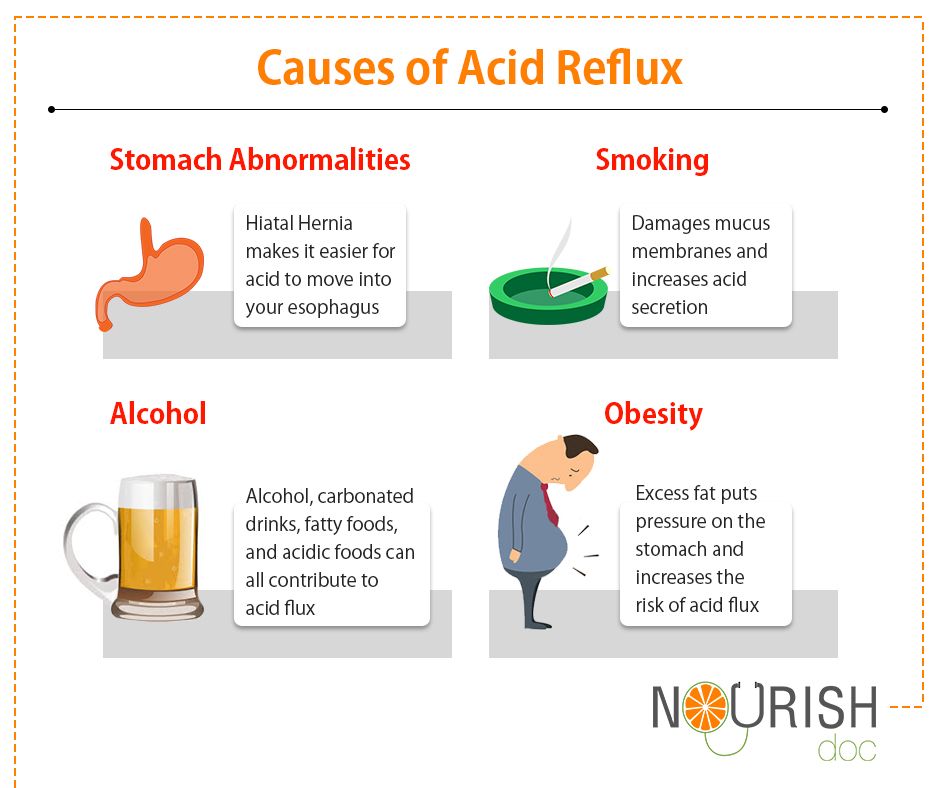

Many parents have found that when introducing solid foods to their baby with infant reflux that some fruits and juices like oranges, apples, and tomatoes make the reflux worse.

Let’s take a look at a list of foods that increases the amount of burping and therefore may worsen an infant’s reflux.

- Brussel sprouts

- broccoli

- corn

- cucumber

- cabbage

- cauliflower

- garlic

- onions

The above foods only increase the amount of burping, and may make reflux worse, but the foods below are common triggers of reflux flares and should be avoided when you have a baby with infant reflux:

- whole milk

- sausage

- bacon

- pineapple

- high fat foods

- carbonated drinks

- creamed vegetables

This is a common list of foods known to trigger reflux flares, but your baby may be triggered by something else. Pay attention to your baby’s diet and how they respond to it especially if your baby has infant reflux.

Pay attention to your baby’s diet and how they respond to it especially if your baby has infant reflux.

Is your baby struggling with reflux? What have you tried to find success in soothing your baby’s reflux symptoms? Tell us in the comments!

90,000 20 ways to calm a child with reflux. Your baby from birth to two years20 Ways to Calm a Child with Reflux

The duration and intensity of treatment for reflux depends on how severely the reflux interferes with the child's growth and well-being. The doctor observes the child and prescribes a treatment regimen, but parents are also responsible for most of the treatment. As you will soon learn, children with reflux need special care and attention. The goals of reflux treatment are the comfort of the baby, its optimal development and minimization of possible damage to the esophagus. Treatment is continued until the child's digestive system has matured naturally to overcome reflux. The basis of reflux therapy is the following:

Development of a meal plan and the selection of fast-digesting foods, and it is also necessary to ensure that food remains in the stomach and is not thrown into the esophagus.

The correct position of the body of the child - day and night - so that gravity helps to keep food in the stomach.

Proper care and care of the child , reducing the frequency of crying attacks, since it is crying that increases pressure on the stomach, which, in turn, increases reflux.

Here's how to calm a child with reflux.

Natural education . This style of parenting, when you are as close as possible to your child, reduces the child's need to cry (remember that crying increases reflux) and helps parents build relationships with their own child. Less crying and more interaction with your baby is the best recipe for reflux. Natural parenting (especially the three parts of it: breastfeeding, carrying the baby, and learning to recognize the baby's signals) not only helps to calm the baby if he is hurt, but also helps parents better use their intuition to recognize the baby's body language and those signs that he delivers even before crying and before an attack of reflux, and in time to intervene. The mother, under the influence of increased prolactin and oxytocin, feels more calm and relaxed. But above all, avoid the crowd advising you to let the baby cry. Children with reflux cry because they are in pain. If you do not pay attention to a crying baby, then reflux will only increase. Imagine that your timely response to the baby's crying is the best medicine. (See Chapter 1 for a detailed description of how natural parenting helps both parents and children grow.)

The mother, under the influence of increased prolactin and oxytocin, feels more calm and relaxed. But above all, avoid the crowd advising you to let the baby cry. Children with reflux cry because they are in pain. If you do not pay attention to a crying baby, then reflux will only increase. Imagine that your timely response to the baby's crying is the best medicine. (See Chapter 1 for a detailed description of how natural parenting helps both parents and children grow.)

DR BILL'S NOTE. Don't take it personally that your baby cries a lot. Any child knows that his parents are there and take care of him, even if they can not always relieve his pain.

Hold the baby half upright, especially during feedings . Gravity helps to naturally hold food in the stomach, preventing it from rising up. Carry your baby in a sling most of the day. Do not leave your child to sit in a car seat or high chair for a long time. When sitting, the child bends over, and thus creates pressure on the stomach, which causes reflux in some children.

The baby should be calm after feedings . Carry your baby in your arms or in a sling for at least 30 minutes after feedings. Dance slowly, but don't squat. But above all, do not involve the baby in too active activities or play immediately after feeding. This can cause reflux.

Feed more often, but in small portions . Follow Dr. Bill's rule: half a serving, but twice as often. Less food in the stomach reduces the chance of reflux. More frequent feedings stimulate salivation. Saliva contains a substance called epidermal growth factor that helps heal damaged tissue in the esophagus. It also neutralizes stomach acid and lubricates irritated esophageal mucosa.

Let the baby burp . If the child swallows too much air, the reflux increases. When breastfeeding, let your baby burp when you transfer him from one breast to the other. If the baby is bottle-fed, let him burp a few times throughout the feeding. Some modern feeding systems reduce the amount of air in the bottle.

Breastfeed . Breast milk is often referred to as an easy-in and easy-out food. Typically, breastfed babies don't have as much reflux as formula-fed babies. And a breastfeeding mother copes with the problem more easily for the following reasons:

• Breast milk "evacuates" from the stomach much faster than formula.

• Breast milk has a better effect on the intestinal microflora.

• Breastfed babies naturally have more feedings per day, and breastmilk is a natural antacid (acid-reducing agent).

• Breastfed babies have softer stools and are rarely constipated.

• Maternal hormones released during breastfeeding allow the mother to relax.

NOTE TO ONE MOTHER. After four doctors, Jacob was diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux at the age of five months. How glad I am that I did not give up and got to the bottom of the truth, what still hurts my child. One of the drugs given to Jacob was to improve his digestion so that reflux would not occur. I realized: what could be better for a baby than the most easily digestible food in the world - mother's milk! When we went to the specialist recommended by our doctor, he was extremely surprised to see Jacob in such high spirits. He said that most of the children with the same degree of reflux as Jacob's developed poorly and looked very sickly. I'm sure that breastfeeding helped Jacob get better.

I realized: what could be better for a baby than the most easily digestible food in the world - mother's milk! When we went to the specialist recommended by our doctor, he was extremely surprised to see Jacob in such high spirits. He said that most of the children with the same degree of reflux as Jacob's developed poorly and looked very sickly. I'm sure that breastfeeding helped Jacob get better.

Consider food or formula intolerance . In the next chapter we will look at food as the cause of colic. It can also cause reflux. If you are breastfeeding, review your diet. Eliminate dairy and wheat products first. Then check to see if there are any other foods that cause your child to worry about in your diet.

Do not put your baby to bed with a bottle or leave your baby unattended with a bottle . Babies with reflux may choke while feeding and may even experience respiratory arrest.

DR BILL'S ADVICE. The mother of a child with colic is under stress, which negatively affects the milk supply. If there is less milk, the baby becomes even more restless, and the mother gradually refuses to breastfeed. Remember our advice: a child needs a happy, rested mother. Seek help from a lactation consultant to maintain your milk supply, seek help with household chores, and make time for yourself.

If there is less milk, the baby becomes even more restless, and the mother gradually refuses to breastfeed. Remember our advice: a child needs a happy, rested mother. Seek help from a lactation consultant to maintain your milk supply, seek help with household chores, and make time for yourself.

Try pacifier . Although your chest and arms are the best sedatives, for some children with reflux, frequent use of a pacifier helps. This is why breastfeeding mothers find their babies constantly begging for food. (On the other hand, some babies associate feeding with pain and therefore refuse to eat.) Frequent sucking stimulates saliva production, which, as already mentioned, relieves irritation of the esophagus with reflux. However, be careful, sometimes too much sucking on a pacifier can increase reflux as the baby swallows more air. So see what suits your child.

Minimize air intake and gas production . When breastfeeding, make sure your baby latch on properly. If you are bottle feeding, use bottles and nipples to reduce air swallowing. Simethicone preparations have a slight effect. These drugs break up large air bubbles into smaller ones that are easier to pass through the intestines. A large amount of air in the stomach and intestines works like a pneumatic pump, when the stomach filled with air contracts, this can cause reflux.

If you are bottle feeding, use bottles and nipples to reduce air swallowing. Simethicone preparations have a slight effect. These drugs break up large air bubbles into smaller ones that are easier to pass through the intestines. A large amount of air in the stomach and intestines works like a pneumatic pump, when the stomach filled with air contracts, this can cause reflux.

Try only one breast per feed . In the first few minutes of feeding, the baby receives the so-called foremilk, which is rich in lactose. If a baby suckles from one breast for less than 10 minutes, he will most likely burp, as foremilk contributes to gas and bloating. Hold the baby at one breast for 20-30 minutes so that he also receives low-lactose hindmilk. Discuss with your doctor or lactation consultant the use of this technique, known as block feeding, to reduce reflux.

Avoid constipation . The tension caused by constipation increases abdominal pressure and can increase reflux. In addition, food that cannot move further along the filled intestine can be thrown into the esophagus.

In addition, food that cannot move further along the filled intestine can be thrown into the esophagus.

Thicken food . If your baby is formula-fed and ready to start complementary foods (that is, he is about six months old), and if your doctor recommends complementary foods, add two or more tablespoons of rice porridge to each bottle of formula (240 grams). The heavier the food, the better it stays in the stomach. Thicker foods help some babies overcome reflux, and for others, on the contrary, make it worse. I'm not sure how thicker foods help with reflux. Also, too much rice porridge can cause constipation.

DR. BILL'S ADVICE: Because many babies with reflux are also allergic to milk-based formula, try a hypoallergenic formula that digests faster in the stomach than regular formula.

Find a sleeping position that will reduce reflux symptoms . While babies under six months of age are best placed to sleep on their backs, babies with reflux often sleep better on their left side. (On the left side, the entrance to the stomach is higher than the opening of the pylorus, which helps gravity keep food in the stomach.) Discuss with your doctor whether reflux attacks justify sleeping on your stomach or on your side. Otherwise, put the baby to sleep on his back. Also try the following to reduce reflux symptoms:

(On the left side, the entrance to the stomach is higher than the opening of the pylorus, which helps gravity keep food in the stomach.) Discuss with your doctor whether reflux attacks justify sleeping on your stomach or on your side. Otherwise, put the baby to sleep on his back. Also try the following to reduce reflux symptoms:

• Use a chair or box to raise the head of the crib by at least 30°.

• Try the special crib holder. It is fixed around the top of the mattress, like a fitted sheet. Then the fabric is threaded between the baby's legs, like a diaper, and fastened on the stomach with Velcro. The design does not allow the child to slide down from the tilted mattress.

• If your baby sleeps in your bed, use a reflux-reducing pillow available at baby stores.

Do not smoke near your child . Nicotine stimulates acid production and opens the lower esophageal sphincter.

Do not put clothes on your baby that will squeeze the tummy.

Try reflux medication . The following medications can, of course, help reduce the discomfort of reflux and minimize damage to the esophagus. But they can only be used in conjunction with the already described ways to alleviate reflux: natural parenting, the correct position of the child's body and proper feeding.

Antacids. These medicines, available from pharmacies without a prescription, neutralize stomach acid. They are given three to four times a day with meals (the specific drug and dose should be determined by the doctor), and the effect is not long in coming. However, the neutralizing effect lasts only a couple of hours. For older children, it is better to give chewable tablets, as they stimulate salivation, mix with saliva, which helps the antacid coat the esophageal mucosa and better neutralize acid. Long-term use of some antacids can cause constipation or diarrhea.

Acid secretion suppressors. These drugs block changes in the level of acid production in the stomach. The effect will have to wait from 30 minutes to two hours, but it can last up to 8 hours. Such drugs are usually given to the child twice a day. If the symptoms of reflux prevent the child from sleeping, give him the drug an hour before bedtime.

The effect will have to wait from 30 minutes to two hours, but it can last up to 8 hours. Such drugs are usually given to the child twice a day. If the symptoms of reflux prevent the child from sleeping, give him the drug an hour before bedtime.

Drugs that affect gastrointestinal motility. These drugs work in the following way: they increase muscle tone and thereby cause the muscle of the lower esophageal sphincter to tighten or increase the muscle motility of the stomach and upper intestine, and therefore food passes from the stomach to the intestines faster. They are sometimes called prokinetics. Antacids and drugs that block acid secretion do not reduce reflux, but only pain and reduce the negative effect of acid on the esophagus. While drugs that affect motility do reduce reflux symptoms, they may have more side effects.

An individual reflux treatment regimen that is right for your child should be developed exclusively under the supervision of a pediatrician or pediatric gastroenterologist. Do not exceed prescribed dosages of medications and do not use over-the-counter medications without the knowledge of your doctor. All drugs have both positive effects on the body and side effects, and drugs that reduce acidity or block the secretion of gastric juice can only be used when reflux really bothers the child and / or can damage the lining of his esophagus. On the other hand, untreated reflux can lead to serious consequences such as a damaged esophagus or asthma. One of the reasons to be careful with antacids is that the acid produced by the stomach has a positive effect. It promotes better digestion of proteins, some vitamins and minerals. The acid also destroys harmful bacteria that enter the stomach, thereby maintaining the balance of beneficial bacteria in the intestines. And finally, the right amount of gastric juice maintains a balance of hormones that facilitate the passage of food into the intestines. Use antacids only if your reflux symptoms have not improved after you tried the methods above.

Do not exceed prescribed dosages of medications and do not use over-the-counter medications without the knowledge of your doctor. All drugs have both positive effects on the body and side effects, and drugs that reduce acidity or block the secretion of gastric juice can only be used when reflux really bothers the child and / or can damage the lining of his esophagus. On the other hand, untreated reflux can lead to serious consequences such as a damaged esophagus or asthma. One of the reasons to be careful with antacids is that the acid produced by the stomach has a positive effect. It promotes better digestion of proteins, some vitamins and minerals. The acid also destroys harmful bacteria that enter the stomach, thereby maintaining the balance of beneficial bacteria in the intestines. And finally, the right amount of gastric juice maintains a balance of hormones that facilitate the passage of food into the intestines. Use antacids only if your reflux symptoms have not improved after you tried the methods above.

Keep a diary . You need to be a close observer and carefully record any signs of reflux in your child, as the doctor will often base a treatment regimen on your observations. The doctor relies on your observations to change the treatment regimen, drugs and dosages. In your diary, note the child's main symptoms, treatment regimen used, and progress (better, worse, or no change).

Seek support . Ask your doctor which parents whose children also suffer from reflux might be consulted. Reflux has been recognized as one of the causes of colic, frequent respiratory infections and asthma, and therefore, understanding this phenomenon and its timely treatment will soon bring positive results.

PARENT ADVICE: Never give up on what your child is really worried about. Be persistent in getting the medical attention you need.

Additional advice for children from the year . While most children outgrow reflux by their first birthday, some children experience it longer. Try the following tricks for children aged one and older:

Try the following tricks for children aged one and older:

Chew Chew Chew. If you teach your child to take food in small pieces and chew thoroughly, he will swallow less air. In addition, well-chewed food is digested faster in the stomach and passes into the intestines.

Let the child "graze". Frequent, tiny meals help digest food easily (see tips for organizing your baby's "buffet" tray).

Sit quietly and eat. Restless behavior at the table causes the release of acid into the esophagus. Teach your child to sit or stand quietly for half an hour after eating.

Don't eat too much at night. Eat early and save low-fat, fast-digesting foods for an evening snack. It is useful for adults to remember: "Do not eat after nine."

Befriend the blender. Fruit and yogurt smoothies and vegetable purees pass through the stomach quickly and therefore cause less reflux.

Don't let your baby get fat. Obesity contributes to the development of reflux.

Obesity contributes to the development of reflux.

Avoid foods that take a long time to digest. As well as products that increase the secretion of gastric juice and possibly provoke reflux.

This text is an introductory fragment.

9 ways to disobey

9 Ways to Disobey An obedient child is, first of all, a child who is able to listen to the opinions of adults, think over reasonable arguments and stick to them. He is not a puppet at all, following all instructions on demand! What is obedience, in general

Child's sleep

The dream of a child Need for sleep • The baby needs one 1.5–2 hour afternoon rest. • Night sleep should be 10–11 hours.

The impact of divorce on the mental state of the child. The importance of a complete family in a child's life

The impact of divorce on the mental state of the child. The value of a complete family in a child's life “The daughter of my friend did not remember her father, because he left the family when she was only a year old and never asked about him. But one day in kindergarten she suddenly burst into tears and shouted: “My

How to calm a child

How to calm a child Words of comfort are needed for every child: from a baby who cannot sleep, to a teenage girl who has not been noticed by her chosen one, and to a boy who has not received an award or a job that he so aspired to. Parents feel an impulse to caress

Memo for Parents, or Ten Ways to Feed a Capricious

Memo for parents, or Ten ways to feed a capricious So, now we know why babies are naughty and refuse such delicious porridge (soup, potatoes, etc. ). Let's put together all the tricks and branded recipes that will help you still feed the capricious

). Let's put together all the tricks and branded recipes that will help you still feed the capricious

How to calm a sick child

How to calm a sick child Carlson leaned back on the pillow and sighed heavily: “How unhappy all the sick are! How unhappy I am! Give me chocolate now. A. Lindgren Do you love to get sick? No. And if it seems to someone that he loves to get sick, then this is not so. You hardly get

Teach your child to experience triumph. A child's birthday is the best occasion!

Teach your child to experience triumph. A child's birthday is the best occasion! Some people don't like their birthday. They never invite guests or try to move away, they are painful and skeptical about congratulations on duty, they can return a gift ...

Chapter 11 Support Your Child Be prepared to lend a shoulder and support your child with teachers, academics, and sports

Chapter 11 Support your child Be ready to lend a shoulder and support your child in relationships with teachers, in school and in sports. A child is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled. Rabelais Introverted children are born learners, there are 9 of them0003

A child is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled. Rabelais Introverted children are born learners, there are 9 of them0003

Ten Ways to Help Children Build Self-Respect

Ten Ways to Help Children Build Self-Respect Throughout life, your child will experience positive influences (creative) and negative influences (destructive). Parents should have a creative influence on the child and teach

9 Ways to Reduce Your Child's Risk of SIDS

9 Ways to Reduce Your Child's Risk of SIDS Based on current SIDS research, including our own theories, here are some tips for reducing your child's risk of SIDS.1. Get yourself a good antenatal care. Do your best,

Five ways to protect your baby from excess fat

Five ways to protect your child from excess fat Give your child milk, the calorie content of which is selected individually. Breastfeed. We are convinced that breastfeeding reduces the risk of obesity. Breast milk contains the newly discovered factor

Breastfeed. We are convinced that breastfeeding reduces the risk of obesity. Breast milk contains the newly discovered factor

14 Carrying a child: the art and science of carrying your child

fourteen Carrying a Baby: The Art and Science of Carrying Your Baby The mothers of the restless children we meet in our practice would subscribe to the statement: "As long as I carry my baby, he is calm." Watching parents take advantage more and more

How to calm a screaming child

How to calm a screaming baby Exhausted parents are ready to try anything. This is the key to the solution - try everything. Most ways to calm a child can be grouped into four categories: • soothing rhythmic movements; • relaxing

Seven ways to make your child smarter

Seven ways to make your child smarter You can influence the development of your child's brain. The latest research on how children's brains work has shown that parents can influence how smart their child becomes. The human brain grows the most at

The latest research on how children's brains work has shown that parents can influence how smart their child becomes. The human brain grows the most at

How to soothe a cough

How to calm a cough That never-ending irritable cough that stretches your nerves to the limit or makes caregivers send your child home from kindergarten does not always need to be stopped. That annoying cold noise can be your best friend. Allocations,

Gastroenterological aspects of the management of children with cerebral palsy (literature review) | Kamalova A.A., Rakhmaeva R.F., Malinovskaya Yu.V.

The article deals with the main gastroenterological disorders most often observed in children with cerebral palsy, and methods for their correction.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of stable disorders of motor development and postural maintenance, leading to motor defects caused by non-progressive damage and/or anomaly of the developing brain in the fetus or newborn child [1]. Movement disorders in cerebral palsy are often combined with sensory disorders, cognitive decline, speech and behavioral disorders, epilepsy, and neuroorthopedic complications. In addition, frequent companions of cerebral palsy are gastroenterological problems, which can be conditionally divided into difficulties associated with nutrition, and the actual pathology of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Nutritional disorders in children with cerebral palsy include various degrees of underweight, growth failure, micronutrient deficiencies, osteopenia, and obesity [2]. The most common gastrointestinal manifestations are dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and constipation. According to various estimates, the prevalence of gastrointestinal pathology among children with cerebral palsy reaches 70%, and nutritional status disorders are detected on average in half of children with cerebral palsy. The reason for such a high prevalence of gastroenterological problems are structural disorders not only of the central, but also of the peripheral nervous system [3].

Movement disorders in cerebral palsy are often combined with sensory disorders, cognitive decline, speech and behavioral disorders, epilepsy, and neuroorthopedic complications. In addition, frequent companions of cerebral palsy are gastroenterological problems, which can be conditionally divided into difficulties associated with nutrition, and the actual pathology of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Nutritional disorders in children with cerebral palsy include various degrees of underweight, growth failure, micronutrient deficiencies, osteopenia, and obesity [2]. The most common gastrointestinal manifestations are dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and constipation. According to various estimates, the prevalence of gastrointestinal pathology among children with cerebral palsy reaches 70%, and nutritional status disorders are detected on average in half of children with cerebral palsy. The reason for such a high prevalence of gastroenterological problems are structural disorders not only of the central, but also of the peripheral nervous system [3]. In the most severe and uncorrected cases, there is an inability to take food through the mouth, which leads to unreasonably long tube feeding, cachexia, severe micronutrient deficiency, a decrease in the rehabilitation potential and quality of life of a child with cerebral palsy and his family.

In the most severe and uncorrected cases, there is an inability to take food through the mouth, which leads to unreasonably long tube feeding, cachexia, severe micronutrient deficiency, a decrease in the rehabilitation potential and quality of life of a child with cerebral palsy and his family.

In recent years, special attention has been paid to the assessment, prevention and treatment of gastroenterological diseases and nutritional status disorders in children with neurological diseases, in particular cerebral palsy. The relevance of this area is confirmed by the results of the work of the experts of the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterologists, Hepatologists and Nutritionists (ESPGHAN), who in 2017 issued “Clinical guidelines for the assessment and treatment of gastrointestinal and nutritional complications in children with neurological disorders” [2]. This document reflects the main problems and their possible solutions to date.

Let's consider the main gastroenterological disorders most often observed in children with cerebral palsy, and methods for their correction.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is an isolated or sequential dysfunction of the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal phases of swallowing. Isolated violations of swallowing are possible in each of the phases, but more often dysphagia is mixed, namely, oropharyngeal in nature [3, 4].

Disorders of the oral phase of swallowing (I phase) are manifested by a violation of the formation of the food bolus. The reasons may be the absence or decrease in the skill of chewing, pseudobulbar paralysis, unextinguished reflexes of newborns, altered palatine and pharyngeal reflexes, the inability to close the lips tightly due to hypersalivation, malocclusion. The most effective measures in violation of this phase of swallowing are: more thorough grinding of food, separation into liquid and solid parts in order to obtain a homogeneous food mass, a change in feeding technique, in particular, when food is placed behind the cheek, in the middle of the tongue, on the root, etc. [4].

Violations of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing (phase II) are manifested by asynchrony in the act of swallowing and breathing. In these cases, thickening of food with the help of thickeners, its grinding, changes in taste and temperature help to correct dysphagia in these cases. Thus, the temperature of food or drink, equal to 36°C, causes the greatest problems in violation of this phase of swallowing, so the proposed products should be either colder (less than 34°C) or hotter (more than 38°C) [5, 6].

In these cases, thickening of food with the help of thickeners, its grinding, changes in taste and temperature help to correct dysphagia in these cases. Thus, the temperature of food or drink, equal to 36°C, causes the greatest problems in violation of this phase of swallowing, so the proposed products should be either colder (less than 34°C) or hotter (more than 38°C) [5, 6].

Dysphagia associated with a violation of the III phase of swallowing - esophageal, in children with cerebral palsy occurs equally often when taking solid and liquid food, may be accompanied by pain in the chest, epigastrium, vomiting. In esophageal stenosis <15 mm, dysphagia occurs only with solid foods. In this case, children need to drink food with plenty of water to push it through the narrowed lumen. The causes of esophageal dysphagia in children with cerebral palsy are most often peptic strictures of the esophagus; diffuse muscle spasm of the esophagus in children with severe spasticity (in children with a score of 4–5 on the Modified Ashworth Scale of muscle spasticity) [6] and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). In a retrospective study by A. Napolis et al. with the participation of 131 children with cerebral palsy, 7 children were diagnosed with EoE [7]. In the general population of children, the prevalence of EoE is 0.16–0.89per 10 thousand people [8]. The data obtained by the authors indicate a significantly higher prevalence of EoE among children with cerebral palsy [7, 8]. The features of the clinical picture of EoE are the frequency of esophageal dysphagia, aggravated allergic history, resistance to standard therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI), characteristic endoscopic and morphological changes in the esophageal mucosa. To exclude esophageal dysphagia in children with cerebral palsy, a consultation with a gastroenterologist, thoracic surgeon is indicated [9].

In a retrospective study by A. Napolis et al. with the participation of 131 children with cerebral palsy, 7 children were diagnosed with EoE [7]. In the general population of children, the prevalence of EoE is 0.16–0.89per 10 thousand people [8]. The data obtained by the authors indicate a significantly higher prevalence of EoE among children with cerebral palsy [7, 8]. The features of the clinical picture of EoE are the frequency of esophageal dysphagia, aggravated allergic history, resistance to standard therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI), characteristic endoscopic and morphological changes in the esophageal mucosa. To exclude esophageal dysphagia in children with cerebral palsy, a consultation with a gastroenterologist, thoracic surgeon is indicated [9].

Symptoms suggestive of dysphagia:

coughing or coughing before, during, or after swallowing;

voice changes during or after swallowing, such as a "wet", "gurgling" voice, hoarseness, temporary loss of voice;

difficulty breathing, shortness of breath after swallowing;

difficulty chewing;

drooling or inability to swallow saliva;

food falling out of the mouth during eating due to incomplete closure of the lips or incorrect movements of the tongue during swallowing, when the tongue presses forward instead of moving up and back;

regurgitation;

"blurred" speech.

Many of these symptoms are characteristic of oropharyngeal dysphagia, the most significant form of dysphagia, which has the worst prognosis over time. Sometimes dysphagia can be indicated by frequent aspiration bronchopneumonia, or the so-called "silent" aspirations with slow flow of food into the respiratory tract [6].

The prevalence of dysphagia among children with cerebral palsy is very high and amounts to more than 90%. Thus, in a study that included 166 children with neurological disorders, 99% had dysphagia: 8% had a mild degree, 76% had a moderate degree, and 15% had a severe degree [6, 10]. Severity was assessed by the clinical picture, observation of the process of eating and the scale Dysphagia Disorders Survey.

A direct correlation was found between the severity of dysphagia and motor disorders according to the GMFCS (Gross Motor Function Classification System) [6]. Severe dysphagia and associated complications have been observed in children with cerebral palsy with GMFCS scores IV and V who needed transfer or were already on gastrostomy feeding.

The diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia is established on the basis of typical complaints and the clinical picture, the evaluation of which must necessarily include the collection of anamnesis data on the child's nutrition in neonatal and infancy. Ask specifically about problems with sucking and/or swallowing. In a study involving 136 children with developmental disorders and damage to the nervous system (children with extremely low birth weight, who underwent hypoxia and asphyxia at birth, with chromosomal abnormalities, genetic syndromes, etc.) aged 0 to 12 months. evaluated the function of swallowing and the process of feeding using special scales. During the study, a high prevalence of various variants of dysphagia was revealed in children, and groups were identified for early intervention to correct dysphagia [11].

The main methods for assessing the severity of oropharyngeal dysphagia are direct observation of the process of eating and the use of special scales - DDS, EDACS, SOMA, FEEDS, etc. [2]. Consider the characteristics of each of them.

[2]. Consider the characteristics of each of them.

DDS (The Dysphagia Disorder Survey) is an advanced system for assessing all variants of dysphagia and consists of two parts. The first part is designed to assess the following indicators: body mass index (BMI), independence in the process of eating, the ability to control body position during meals, the consistency of food consumed by the subject, the use of special utensils, feeding techniques and positional management techniques. The second part evaluates the process of feeding and swallowing function, includes questions clarifying which of the phases of swallowing are disturbed - oral, oropharyngeal and esophageal. Food types of different consistencies were selected as instruments for assessing chewing and swallowing skills: liquid, solid food that did not require chewing, and solid food that required chewing. This scale is used in adults and children older than 2 years [12].

EDACS (Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System) is an easy-to-use algorithm for classifying the ability to eat safely. The questionnaire assesses the ability to eat solid and liquid food without the risk of aspiration. Depending on the quantity and quality of restrictions, the level is determined on a scale - from level I, at which there are no violations, to V, when only tube feeding is possible. With an increase in the level on the EDACS scale, the risk of complications during oral feeding (aspiration, weight loss) increases [5].

The questionnaire assesses the ability to eat solid and liquid food without the risk of aspiration. Depending on the quantity and quality of restrictions, the level is determined on a scale - from level I, at which there are no violations, to V, when only tube feeding is possible. With an increase in the level on the EDACS scale, the risk of complications during oral feeding (aspiration, weight loss) increases [5].

The SOMA (Schedule for Oral Motor Assessment) scale is designed to objectively assess the development of oral motor skills in children aged 8 to 24 months. The purpose of the scale is to identify at the level of which part of the gastrointestinal tract involved in the act of swallowing, there is a violation, due to which there are difficulties with feeding [6].

The FEEDS (Functional Evaluation of Eating Difficulties Scale) scale is a checklist that consists of 4 sections: in the 1st section, the structural and functional viability of the lips, tongue, jaws, sensitivity of the perioral region and oral mucosa are assessed; in the 2nd section, the safety and severity of the main oropharyngeal reflexes are checked - sucking, swallowing, coughing, etc. ; the 3rd section is devoted to assessing the state of the autonomic nervous system; in the 4th section, other clinical signs are revealed: symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, inability to swallow, respiratory disorders, etc. The advantage of this scale is the possibility of its use in young children, from birth [13].

; the 3rd section is devoted to assessing the state of the autonomic nervous system; in the 4th section, other clinical signs are revealed: symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, inability to swallow, respiratory disorders, etc. The advantage of this scale is the possibility of its use in young children, from birth [13].

The "gold standard" for the diagnosis of dysphagia is videofluoroscopy, which allows to detect discoordination of pharyngeal motility, "silent" aspirations, loose closure of the lips, improper formation of the food bolus, food debris in the oral cavity, delay in the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, plaque on the walls of the pharynx, delay in the passage of the food bolus along pharynx. This method allows you to choose the necessary strategy for feeding a child with cerebral palsy in the future [2].

The main goal of correcting dysphagia in children with cerebral palsy is to optimize safe food intake per os , especially in the following cases: with habitual refusal to eat per os ; the process of eating is tiring for the child and is perceived by him as "work"; when oral motor dysphagia is the result of an unformed skill of a full meal per os . The management of patients with dysphagia requires a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach. With mild and moderate oropharyngeal dysphagia, the necessary and sometimes sufficient correction measures are: changing the duration of meals individually for each child, taking into account his capabilities, positional management - ensuring the correct and safe position of the body and head of the child during meals, thickening food. It should be noted that liquid foods and drinks are considered less safe due to the greater risk of aspiration compared to foods with a denser consistency. At the same time, in patients with severe dysphagia who are on tube feeding or feeding through a gastrostomy, it is desirable to use the methods of restoring the chewing and swallowing processes used by speech therapists and speech therapists in the future. When used successfully, these techniques can help, over time, to return to the natural way of eating and drinking, to expand the diet and reduce the risk of aspiration [2, 14].

The management of patients with dysphagia requires a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach. With mild and moderate oropharyngeal dysphagia, the necessary and sometimes sufficient correction measures are: changing the duration of meals individually for each child, taking into account his capabilities, positional management - ensuring the correct and safe position of the body and head of the child during meals, thickening food. It should be noted that liquid foods and drinks are considered less safe due to the greater risk of aspiration compared to foods with a denser consistency. At the same time, in patients with severe dysphagia who are on tube feeding or feeding through a gastrostomy, it is desirable to use the methods of restoring the chewing and swallowing processes used by speech therapists and speech therapists in the future. When used successfully, these techniques can help, over time, to return to the natural way of eating and drinking, to expand the diet and reduce the risk of aspiration [2, 14].

Thus, dysphagia is a complex, relevant and common problem in children with cerebral palsy. According to the ESPGHAN clinical guidelines, the diagnosis of dysphagia should be based on the clinical picture, data from special standardized and reliable scales (Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System, the Schedule for Oral Motor Assessment, Dysphagia Disorders Survey, etc.) and videofluoroscopy [2]. Management of patients with dysphagia requires a comprehensive multidisciplinary and differentiated approach depending on the type and severity of dysphagia.

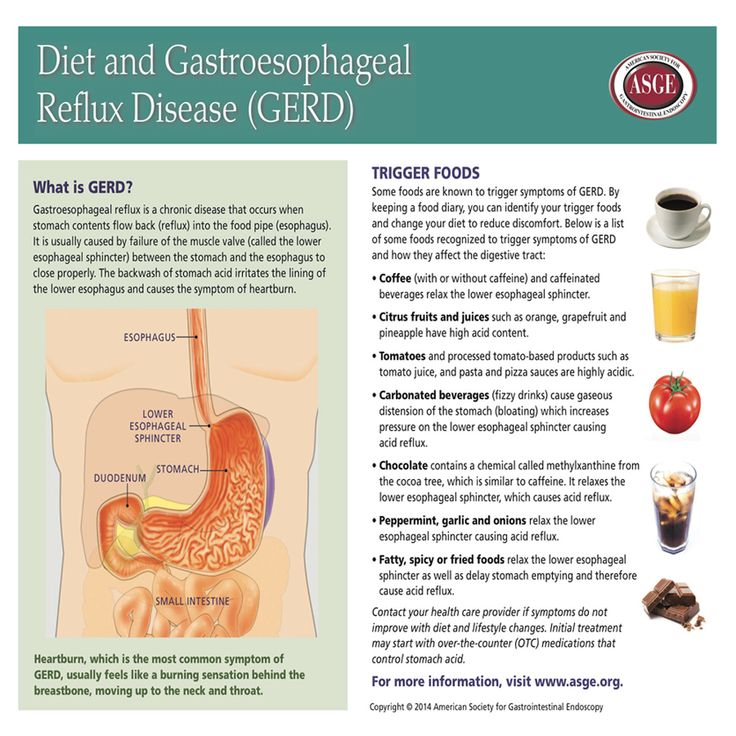

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

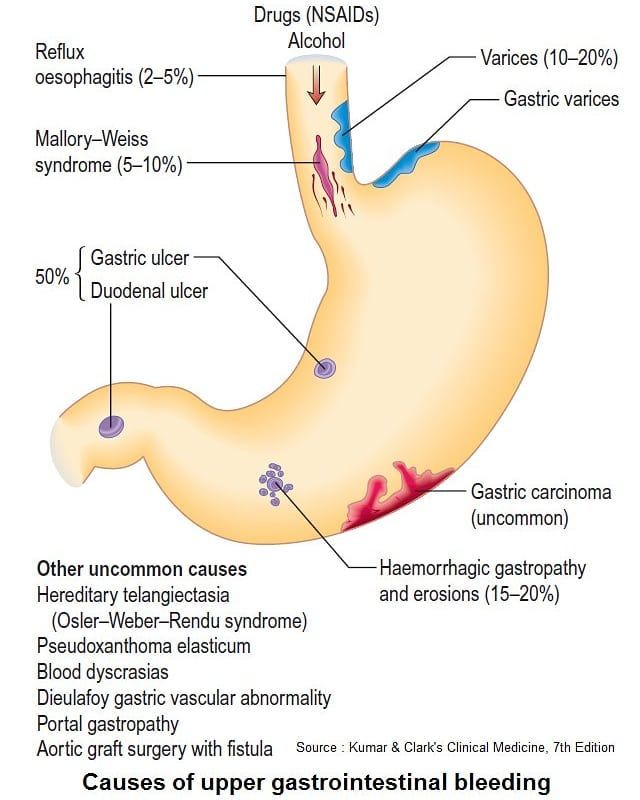

Gastroesophageal reflux occurs when involuntary retrograde reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease ( GERD) in cerebral palsy, according to various sources, reaches 70% [15].

In children with cerebral palsy with severe limitation of motor functions, there are risk factors for the development of GERD: impaired innervation of smooth muscle cells of the gastrointestinal tract, which leads to a decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, the rate of gastric emptying, impaired motility of the esophagus; general spasticity; inability to maintain posture, short duration of verticalization; convulsive syndrome; taking antiepileptic drugs; violation of posture, etc. [16].

[16].

Symptoms of GERD:

regurgitation of gastric contents without previous nausea and any effort;

nausea followed by vomiting caused by the contraction of the abdominal muscles and the effort of the patient;

retrosternal pain, heartburn, crying, irritability and sleep disturbances;

episodes of aspiration and respiratory manifestations: chronic nocturnal cough, recurrent pneumonia, bronchial hyperreactivity of non-allergic origin;

bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract;

chronic esophagitis, esophageal ulcer, Barrett's esophagus, Sandifer's syndrome, including hernia of the esophageal part of the diaphragm, reflux esophagitis, torticollis, arbitrary "writhing" movements of the head and neck, anemia;

refusal to eat;

erosion of tooth enamel;

increased dystonia and spasticity;

growth stagnation, anemia, hypoproteinemia associated with eating disorders or refusal to eat [17].

Respiratory symptoms, which are common in children with cerebral palsy, can also exacerbate GERD. Despite the high prevalence of GERD among children with cerebral palsy, the symptoms of the disease are not very specific, and children in this group cannot always express their complaints. Therefore, GERD in children with cerebral palsy is often diagnosed already at the stage of erosive esophagitis or esophageal ulcers or in the case of recurrent aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia and refusal to eat, which are common in GERD, can be a serious obstacle in the implementation of effective nutritional support for children with cerebral palsy and are unfavorable prognostic factors. Therefore, GERD is another "red flag" in assessing the health status of children with cerebral palsy [2].

Diagnosis of GERD is based on a combination of clinical manifestations and these instrumental methods. It is necessary to note the extreme importance of the clinical diagnosis of GERD in patients with cerebral palsy due to the high prevalence of this pathology, as well as the complexity of organizing and conducting endoscopic examination and pH-impedancemetry. The clinician should evaluate the benefit/risk ratio of the study and the need for concomitant sedation of the patient during the examination. Given the high prevalence of GERD and the vulnerability of this group of patients in the presence of an appropriate clinical picture, trial treatment with proton pump inhibitors without endoscopic confirmation of reflux esophagitis is considered acceptable, subject to careful monitoring [25]. Nevertheless, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is the method of choice for diagnosing the depth and localization of damage to the esophageal mucosa. Biopsy is important to confirm or rule out other non-reflux causes of esophagitis, and also if Barrett's transformation is suspected. Gastroesophageal scintigraphy is performed to confirm pulmonary microaspiration [2].

The clinician should evaluate the benefit/risk ratio of the study and the need for concomitant sedation of the patient during the examination. Given the high prevalence of GERD and the vulnerability of this group of patients in the presence of an appropriate clinical picture, trial treatment with proton pump inhibitors without endoscopic confirmation of reflux esophagitis is considered acceptable, subject to careful monitoring [25]. Nevertheless, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is the method of choice for diagnosing the depth and localization of damage to the esophageal mucosa. Biopsy is important to confirm or rule out other non-reflux causes of esophagitis, and also if Barrett's transformation is suspected. Gastroesophageal scintigraphy is performed to confirm pulmonary microaspiration [2].

According to the study by G. Caltepe et al., alkaline reflux was more often diagnosed in children with cerebral palsy based on the results of intraesophageal pH-impedancemetry [19]. The advantage of pH-impedancemetry lies in the possibility of diagnosing both acidic and weakly acidic and alkaline refluxes, which allows choosing the right tactics for managing a patient [20].

In children with persistent gastrostasis, to exclude intestinal obstruction, it is necessary to conduct an X-ray contrast study of the esophagus and stomach with barium and / or ultrasound of the abdominal organs. In addition, patients with cerebral palsy and severe neurological deficits are at risk of developing superior mesenteric artery syndrome, since the combination of scoliosis and malnutrition leads to a decrease in the fat layer in the retroperitoneal region around the third - horizontal - part of the duodenum, which normally protects against compression. superior mesenteric artery in the region of the aorto-mesenteric angle [21].

Treatment of GERD in children with cerebral palsy includes lifestyle changes, diet therapy, medication, and surgery.

The impact of nutritional intervention on the course of GERD in children with cerebral palsy has been studied in several studies. So, R. Miyazawa et al. noted the positive effect of the use of a food thickener - pectin on the severity of GERD symptoms in 18 children with cerebral palsy [22]. V. Khoshoo et al. distributed children with cerebral palsy, who are fed exclusively through a gastrostomy, into 2 groups. The 1st was fed a casein-dominant formula, and the 2nd was fed a whey protein-based formula. A significant decrease in the number of episodes and duration of reflux was recorded in the group of children receiving a formula based on whey protein, which may be due to faster evacuation of food from the stomach [23].

V. Khoshoo et al. distributed children with cerebral palsy, who are fed exclusively through a gastrostomy, into 2 groups. The 1st was fed a casein-dominant formula, and the 2nd was fed a whey protein-based formula. A significant decrease in the number of episodes and duration of reflux was recorded in the group of children receiving a formula based on whey protein, which may be due to faster evacuation of food from the stomach [23].

Antisecretory drugs are considered first-line therapy in children with cerebral palsy with signs of GERD. It is known that PPIs are superior in effectiveness to H 2 -histamine receptor blockers both in the treatment of erosive esophagitis and in the reduction of symptoms of GERD [20]. However, PPIs do not affect the volume and number of reflux episodes, so symptoms such as nausea persist despite therapy. As with all long-term PPI use, special attention should be paid to side effects such as pulmonary and gastrointestinal infections and micronutrient malabsorption.

The efficacy and safety of the use of prokinetics, in particular metoclopramide, domperidone and erythromycin, in the treatment of GERD in children with cerebral palsy have not been studied. Therefore, the routine prescription of this group of drugs for children with cerebral palsy is not recommended.

Monitoring the effectiveness of GERD therapy in patients with cerebral palsy is carried out using instrumental diagnostic methods (mainly endoscopy). When there is a need for long-term PPI therapy, intraesophageal pH-impedancemetry with or without esophageal pH-metry is the “gold standard” for monitoring the effectiveness of treatment.

Indications for surgical treatment of GERD in children with cerebral palsy are: a) repeated episodes of apnea, bradycardia, recurrent pneumonia; b) Barrett's esophagus; c) the need for a gastrostomy in combination with indications a) and b).

The high prevalence of dysphagia (severe, inability to eat through the mouth due to stenosis or stricture of the esophagus) and GERD in children with cerebral palsy often leads to complications, namely nutritional status disorders, weight loss with micronutrient deficiencies, an increase in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia and high mortality in this group of patients [17, 18]. An important pathogenetic role is played by the nutritional status and adequate nutrition of the child. If it is impossible to provide the child's basic needs for energy and nutrients in a natural way, if therapy aimed at correcting dysphagia and GERD is ineffective, it becomes necessary to switch to enteral nutrition.

An important pathogenetic role is played by the nutritional status and adequate nutrition of the child. If it is impossible to provide the child's basic needs for energy and nutrients in a natural way, if therapy aimed at correcting dysphagia and GERD is ineffective, it becomes necessary to switch to enteral nutrition.

Prospective randomized trials comparing the efficacy and safety of feeding children with cerebral palsy through a nasogastric tube and a gastrostomy have not been conducted. A Cochrane review comparing tube versus gastrostomy feeding in adult patients found benefits of gastrostomy feeding, namely a lower complication rate, less feeding discomfort, and greater social engagement. There were no significant differences in mortality rates associated with aspiration and aspiration pneumonia. Thus, the application of a gastrostomy is more effective and safer than the use of a nasogastric tube [24]. A prospective cohort study, including a 12-month follow-up of 57 children with neurological disorders, including cerebral palsy, fed through a gastrostomy, showed a significant improvement in weight curves, health status and quality of life, a significant reduction in the time of one feeding. In addition, gastrostomy feeding did not increase the frequency of episodes of respiratory infections.

In addition, gastrostomy feeding did not increase the frequency of episodes of respiratory infections.

Locks

A serious comorbid condition in children with cerebral palsy is constipation. The pathogenesis of constipation in children with cerebral palsy is complex and includes both functional and organic components.

R.Veugelers et al. conducted a study of constipation in 152 children with neurological disorders and formulated the following definition of constipation: the presence of hard, stone-like stools in more than 25% of bowel movements, the frequency of bowel movements less than 3 times a week, palpable feces through the anterior abdominal wall, regular use of laxatives or passing stool only after a cleansing enema. This definition is based on the Rome III criteria and criteria for the diagnosis of functional constipation in adults with disabilities [25].

The Rome Criteria, Revision IV, are currently used to diagnose functional constipation in children [26].

Diagnostic criteria for functional constipation in children under 4 years of age:

Presence of 2 or more symptoms within 1 month:

2 or fewer bowel movements per week;

excessive stool retention in history;

defecation, accompanied by pain and straining in history;

a large diameter of fecal masses in history;

the presence of a large amount of feces in the rectum.

In potty trained children, additional criteria may be used:

one or more episodes of stool incontinence per week after toilet training;

a history of large diameter fecal masses causing clogging of the toilet bowl [26].

Diagnostic criteria for functional constipation in children older than 4 years:

The presence of 2 or more symptoms occurring at least once a week for at least 1 month. with insufficient criteria for diagnosing IBS:

2 or fewer bowel movements per week;

1 or more episodes of stool incontinence per week;

episodes of deliberate retention of stool in the intestines;

episodes of painful or difficult bowel movements;

the presence of a large amount of feces in the rectum;

large-diameter stool that can cause blockage of the drain [27].

In children with cerebral palsy, there are a number of factors that predispose to the development of constipation. Firstly, the nature of the disease itself lies in the defeat of both central and peripheral nervous structures. It is known that the enteric nervous system (submucosal and mesenteric nerve plexus) serves as a coordinator of intestinal peristalsis and is represented by a complex of a highly integrated network of neurons, the activity of which is regulated by a wide range of impulses emanating from the central nervous system (CNS). Therefore, a common mechanism for the development of gastrointestinal disorders is a violation of the motility of the gastrointestinal tract [3, 27]. J. Johanson et al. in a retrospective study of a general hospital population of patients with neurological diseases, CNS damage was identified as a significant risk factor for the development of constipation [28]. Secondly, the nutritional factor in children with cerebral palsy. The diet of children in this group, especially those with severe neurological manifestations (GMFCS IV-V) and dysphagia, is dominated by homogenized food with a low fiber content. Fluid deficiency is the result of an involuntary refusal of liquid forms of food, since it causes the greatest difficulty in swallowing. Expansion of the diet and increased fluid intake are hindered by fear of choking and aspiration [3, 29, thirty]. Thirdly, limitation of physical activity makes a great contribution to the development of constipation in children with cerebral palsy. Thus, the inability to maintain a posture, to sit independently limits the ability to put such children on the potty and instill toilet skills, to defecate in the most physiological position [42]. In addition, children with severe spasticity (score 3–5 on the Modified Ashworth Spasticity Scale) often have signs not only of diffuse muscle spasm of the esophagus, but also of the intestinal sphincter apparatus [14]. Fourth, constipation may be related to therapy given to children with cerebral palsy. Constipation is a proven side effect of valproates, phenothiazines, and baclofen. And, finally, intellectual deficiency causes the ineffectiveness of many preventive measures and therapeutic measures for constipation in children with cerebral palsy [27].

Fluid deficiency is the result of an involuntary refusal of liquid forms of food, since it causes the greatest difficulty in swallowing. Expansion of the diet and increased fluid intake are hindered by fear of choking and aspiration [3, 29, thirty]. Thirdly, limitation of physical activity makes a great contribution to the development of constipation in children with cerebral palsy. Thus, the inability to maintain a posture, to sit independently limits the ability to put such children on the potty and instill toilet skills, to defecate in the most physiological position [42]. In addition, children with severe spasticity (score 3–5 on the Modified Ashworth Spasticity Scale) often have signs not only of diffuse muscle spasm of the esophagus, but also of the intestinal sphincter apparatus [14]. Fourth, constipation may be related to therapy given to children with cerebral palsy. Constipation is a proven side effect of valproates, phenothiazines, and baclofen. And, finally, intellectual deficiency causes the ineffectiveness of many preventive measures and therapeutic measures for constipation in children with cerebral palsy [27].

According to the ESPGHAN recommendations for nutrition and management of children with neurological disorders in children with constipation, a digital rectal examination should be performed once, as this makes it possible to assess the sensitivity of the perianal zone, the size of the rectum, the preservation of the anal reflex, determine the amount and consistency of stool, and also location within the rectum [2]. But in a number of publications there is information about the negative attitude of local ethical committees to digital rectal examination, which consider this procedure invasive and unethical [30].

Abdominal x-ray is not used to routinely diagnose functional constipation; conventional x-ray examination of the abdominal cavity can be used in cases of colostasis, when an objective examination is not possible or its results are uninformative [26].

X-ray contrast examination of the gastrointestinal tract (barium passage) can be used in the differential diagnosis of functional constipation and functional fecal incontinence, as well as in unclear cases [30]. Irrigography, colonic manometry, magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord, biopsy of the colon are not recommended in the routine practice of examining children with cerebral palsy. Indications are virtually the same in children of the general population [28].

Irrigography, colonic manometry, magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord, biopsy of the colon are not recommended in the routine practice of examining children with cerebral palsy. Indications are virtually the same in children of the general population [28].

The complexity of the treatment of constipation in children with cerebral palsy is beyond doubt and is due to many predisposing factors, chronic course and refractoriness to standard therapy. Early detection of problems with defecation, warning parents about the need to control pain in a child during defecation are the first steps in organizing competent treatment of children in this group [2, 29].

First of all, nutritional preventive measures are important: adding fiber to the diet up to 17–21 g/day and drinking enough liquid (Table 1). For children who are on tube feeding and feeding through a gastrostomy, the use of special therapeutic mixtures enriched with fibers is recommended. Controlling the amount of fluid consumed and increasing its volume are especially recommended for children with cerebral palsy with hypersalivation and GER. In uncomplicated cases, these measures are sufficient even in the case of refusal of laxatives [2, 25, 27].

In uncomplicated cases, these measures are sufficient even in the case of refusal of laxatives [2, 25, 27].

An important principle in the treatment of constipation is the effective emptying of the intestines and the establishment of a regular and painless bowel movement. For this purpose, a cleansing enema is used for 3 days or oral administration of an osmotic laxative based on polyethylene glycol (PEG) at a dosage of 1.5 g / kg / day. Maintenance therapy includes the appointment of osmotic laxatives - lactulose (1-2 ml / kg / day) in children from birth or a PEG-based drug (0.8 g / kg / day) in children from 6 months. The duration of maintenance therapy is variable, the patient must be free of symptoms of constipation for at least 1 month. before deciding whether to discontinue therapy. Cancellation of laxatives should occur gradually, against the background of assessing the regularity and painlessness of defecation [2].

There are reports in the literature of the development of severe pneumonia due to aspiration of laxatives, so the use of macrogol or liquid paraffin (mineral oil) should be cautious and limited in children with cerebral palsy with signs of GERD and a high risk of aspiration [29].