Twist baby food

A concise history of infant formula (twists and turns included)

| Jump to: | Choose article section... From wet nursing to dry nursing The search for a breast milk substitute Physicians take charge Pasteurization and healthier milk Big breakthrough: Evaporated milk Seeking a "humanized" formula The rise of proprietary formulas The modern era: Fine-tuning formulas The pediatrician's infant formula trivia quiz |

By Andrew J. Schuman, MD

Finding an acceptable alternative to breast milk has proved to be a complicated quest that continues today with an ever-growing assortment of modified and specialized infant formulas.

If you are a "mature" pediatricianone older than 40 years or sothere is a good chance that, if you were not breastfed as an infant, you were fed a formula created by mixing 13 oz of evaporated milk with 19 oz of water and two tablespoons of either corn syrup or table sugar. Every day, parents prepared a day's worth of this formula, transferred it to bottles that they had sterilized in a pan of boiling water, and stored it in a refrigerator until used. In addition to formula, infants received supplemental vitamins and iron.1

Infant nutrition has a fascinating history that began long before pediatricians recommended evaporated milk formula, and eventually commercial formula, as alternatives to breastfeeding. In this first article in an occasional series that puts the practice of pediatrics into historical perspective, we'll take a look at how infant formulas were developed and how they evolved over time.

From wet nursing to dry nursing

Before the era of "modern" medicine, breastfeeding was the preferred method of feeding infants, just as it is today. But if a mother's milk supply was inadequate or she chose not to nurse, the family often employed a "wet nurse" to nourish infants. This practice was common in Europe during the 18th century and in America during the colonial period. Families would hire a wet nurse to reside in the family's home or send the infant to live in the wet nurse's home and retrieve the baby after he or she had been weaned.

Wet nurses were selected with the utmost care, because it was believed the quality of the milk the baby received determined his or her future "disposition." Brunette wet nurses were preferred to blondes or redheads because their breast milk was thought to be more nutritious and their disposition more "balanced."

During the 18th century in Europe, the demand for wet nurses was so great that bureaus were established where wet nurses could register and reside until their services were needed. Governments regulated the bureaus strictly. Laws mandated that wet nurses undergo routine health examinations and prohibited them from nursing more than one infant at a time.

Eventually, wet nursing fell out of favor, and attention turned to finding an adequate substitute for mother's milk.2 The practice of feeding human babies milk from animals, called dry nursing, began to flourish in the 19th century. Milk from a variety animalsgoats, cows, mares, and donkeyswas used. Cow's milk became the most widely used because of its ready availability (although donkey's milk was thought to be healthier because its appearance most closely resembled that of human milk). Physicians argued about the best way to prepare milk. Some suggested giving it fresh from the animal, while others recommended that it be warmed or boiled first, and still others suggested diluting it with water and adding sugar or honey.3

Cow's milk became the most widely used because of its ready availability (although donkey's milk was thought to be healthier because its appearance most closely resembled that of human milk). Physicians argued about the best way to prepare milk. Some suggested giving it fresh from the animal, while others recommended that it be warmed or boiled first, and still others suggested diluting it with water and adding sugar or honey.3

Before the baby bottle came into use, milk was spoon fed to infants or given via a cow's horn fitted with chamois at the small end as a nipple. When baby bottles were adopted during the Industrial Revolution, many popular designs evolved. Some were submarine-shaped and made from metal, glass, or pottery. They had a circular opening in the top that could be occluded with a cork, and one end tapered to a hole with a rim for securing a nipple. Another popular design was the spouted feeder, which resembled a teapot and was equipped with a handle and a long spout that terminated in a nipple-shaped bulb. The nipple opening of both types of bottles was covered with punctured chamois cloth, parchment, or sponge.2 Rubber nipples became widely available and very popular after their invention by Elijah Pratt, an American, in 1845.

The nipple opening of both types of bottles was covered with punctured chamois cloth, parchment, or sponge.2 Rubber nipples became widely available and very popular after their invention by Elijah Pratt, an American, in 1845.

After an infant was weaned from breast milk or cow's milk he or she was given an infant food called pap, which consisted of boiled milk or water thickened with baked wheat flour and, sometimes, egg yolk. A more elaborate infant food, called panada, was made from bread, flour, and cereals cooked in a milk- or water-based broth. Detailed recipes for various kinds of infant paps and panadas have been published in cookbooks throughout history.1

The search for a breast milk substitute

A longtime goal of nutritionists and physicians was to develop an adequate breast milk substitute. In the early 19th century, it was observed that infants fed unaltered cow's milk had a high mortality rate and were prone to "indigestion" and dehydration compared with those who were breastfed. In 1838, a German scientist, Johann Franz Simon, published the first chemical analysis of human and cow's milk, which served as the basis for formula nutrition science for decades to follow. He discovered that cow's milk had a higher protein content and a lower carbohydrate content than human milk. In addition, he (and later investigators) believed that the larger curds of cow's milk (compared to the small curds of human milk), were responsible for the "indigestibility of cow's milk."2

In 1838, a German scientist, Johann Franz Simon, published the first chemical analysis of human and cow's milk, which served as the basis for formula nutrition science for decades to follow. He discovered that cow's milk had a higher protein content and a lower carbohydrate content than human milk. In addition, he (and later investigators) believed that the larger curds of cow's milk (compared to the small curds of human milk), were responsible for the "indigestibility of cow's milk."2

Empirically, physicians began to recommend that water, sugar, and cream be added to cow's milk to render it more digestible and closer to human milk. By 1860, a German chemist, Justus von Leibig, developed the first commercial baby food, a powdered formula made from wheat flour, cow's milk, malt flour, and potassium bicarbonate. The formula, which was added to heated cow's milk, soon became popular in Europe. Leibig's Soluble Infant Food was the first commercial baby food in the US, selling in groceries for $1 a bottle in 1869.

In the 1870s, Nestle's Infant Food, made with malt, cow's milk, sugar, and wheat flour, became available in the US, selling for $.50 a bottle. In contrast to Leibig's Food, Nestle's formula was diluted with water only, requiring no cow's milk to prepare, and thus was the first complete artificial formula available in this country.

Several cow's milk modifier formulas were introduced over the next 20 years, and by 1897 the Sears catalogue was selling no fewer than eight brands of commercial infant foods, including Horlick's Malted food ($.75 per bottle), Mellin's Infant Food ($.75 per bottle), and Ridge's Food for Infants ($.65 per bottle).4 Despite their widespread availability, these proprietary formulas realized only modest sales in the late 19th century because they were expensive in comparison to cow's milk. Most mothers continued to breastfeed their infants.

Physicians take charge

In the late 19th century, many physicians thought that infant nutrition should be directed not by formula manufacturers but by physicians themselves. Many believed that commercial formulas were nutritionally inadequate and therefore inappropriate for young infants.

Many believed that commercial formulas were nutritionally inadequate and therefore inappropriate for young infants.

Thomas Morgan Rotch of Harvard Medical School developed what came to be known as the "percentage method" of infant formula feeding, which was popular among medical professionals from 1890 to 1915. He taught that because cow's milk contains more casein than human milk, it must be diluted to lower the percentage of casein. The process of dilution, however, decreases the sugar and fat content to less than that of human milk. To correct these deficiencies, cream and sugar were added in precise amounts.

Cow's milk formulas prescribed by the percentage method were compounded by a milk laboratory or, more often, by a home method that was time and labor intensive. Physicians were taught to monitor growth carefully and to examine the infant's stool and modify the formula based on its appearance.3

By the 1920s, physicians were frustrated by the complexity of formula prescribing and modifications associated with Rotch's percentage method. They eventually began to recommend either commercial formulas or simple homemade formulas made with evaporated milk.

They eventually began to recommend either commercial formulas or simple homemade formulas made with evaporated milk.

Pasteurization and healthier milk

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, physicians came to understand that diseases were caused by germs and could be transmitted by consuming contaminated foodstuffs. In particular, raw milk, which spoiled readily (refrigeration was not widely available until about 1910), was found to transmit a variety of diseases, including tuberculosis, typhoid fever, cholera, and diphtheria.

In 1864, Louis Pasteur discovered that keeping wine at a high temperature killed the bacteria that caused the wine to sour. The pasteurization process was employed by the dairy industry in 1890not to make milk "healthier" but to prevent milk transported in unrefrigerated railroad cars from souring. Several years later, it was discovered that pasteurization also protected against milk-borne diseases.3

Many physicians vigorously opposed pasteurization, however, because they believed that the process significantly diminished the nutritional value of milk. In fact, pasteurized milk was found to be deficient in what were later identified as vitamins C and D, and children consuming pasteurized milk received daily doses of orange juice and cod liver oil (rich in vitamins A and D) to prevent scurvy and rickets. Pasteurization of milk became a universal practice in the US by about 1915.

In fact, pasteurized milk was found to be deficient in what were later identified as vitamins C and D, and children consuming pasteurized milk received daily doses of orange juice and cod liver oil (rich in vitamins A and D) to prevent scurvy and rickets. Pasteurization of milk became a universal practice in the US by about 1915.

Big breakthrough: Evaporated milk

Perhaps the greatest advance in milk science occurred before the Civil War. Gail Borden discovered and patented a process of heating milk to high temperatures in sealed kettles, which removed close to half the water content of the milk. By adding sugar as a preservative to the resulting product, Gail Borden invented sweetened "condensed" milk that had a long shelf life and could be transported easily without fear of spoilage. Condensed milk was an invaluable ration for soldiers during the Civil War and was later promoted to mothers as an infant food. Because of its high sugar content, however, physicians discouraged its use as an infant formula.

A method of producing unsweetened evaporated milk was developed by John B. Myenberg in 1883. The process involved evaporating approximately 60% of the water from milk in a sealed metal still, then sterilizing the condensed milk by heating it to above 200°. This process altered the physical properties of milk, homogenizing it and rendering the curd smaller and more digestible than boiled pasteurized milk. Studies published in the 1920s and 1930s demonstrated that large numbers of babies fed evaporated milk formula grew as well as breastfed infants did.5 Physicians and parents, reassured by this evidence and encouraged by the low cost and widespread availability of evaporated milk, almost universally endorsed evaporated milk formula to feed infants. In the 1930s, physicians were taught to mix evaporated milk formula by combining 2 oz of cow's milk per pound of body weight per day with 18 oz of sugar per pound of weight per day and enough water to provide an infant with 3 oz of fluid volume per pound per day. During the Great Depression, corn syrup replaced sugar as a source of carbohydrate because of cost and availability. Gradually the formula was simplified to the one described at the beginning of this article.

During the Great Depression, corn syrup replaced sugar as a source of carbohydrate because of cost and availability. Gradually the formula was simplified to the one described at the beginning of this article.

By the 1940s and through the 1960s, most infants who were not breastfed received evaporated milk formula, as well as vitamins and iron supplements. It is estimated that, in 1960, 80% of bottle-fed infants in the US were being fed with an evaporated milk formula.3

Seeking a "humanized" formula

In the early 20th century, the focus of nutrition scientists shifted from modifying the protein content of infant formula to making its carbohydrate and fat content more closely resemble that of human milk. Some researchers believed that the carbohydrate content of cow's milk should be supplemented with maltose and dextrins; at their request, E. Mead Johnson, the founder of the Mead Johnson company, produced a cow's milk additive called Dextri-Maltose. Dextri-Maltose was introduced at the 1912 meeting of the American Medical Association (AMA) and was sold only by physicians to mothers.

A few years later, in 1919, a new infant formula was introduced that replaced milk fat with a fat blend derived from animal and vegetable fats. This formula, which more closely resembled human milk than cow's milk, was called SMA (for "simulated milk adapted"). SMA was also the first formula to include cod liver oil. Soon after SMA was introduced, Nestle's Infant Food added cod liver oil to its formula, as did most other infant formulas.4

In the 1920s, other "humanized" infant formulas were produced and marketed to the American public. Nestle produced a formula with a vegetable-oil-derived fat blend, called Lactogen, that was positioned to compete with SMA.

Another humanized infant formula was developed by Alfred W. Bosworth, a milk chemist working for the biochemistry department of Harvard Medical School, and by Henry Bowditch, a Boston pediatrician who was employed at the Boston Floating Hospital. They experimented with an infant formula derived from cow's milk by adding varying amounts of vegetable oils, calcium, and phosphorus salts and preparing blends with different lactose concentrations. Bosworth and Bowditch tested more than 200 formulas in clinical trials before they considered their infant formula complete.

Bosworth and Bowditch tested more than 200 formulas in clinical trials before they considered their infant formula complete.

In 1924, Bosworth agreed to have his formula marketed by the Moores and Ross Milk Company of Columbus, Ohio. The new formula was produced at the Franklin Brewery plant in Columbus and was originally sold by physicians in plain cans upon which they could place their own label. In 1926, the formula was renamed "Similac" because it was "similar to lactation"a name proposed by Morris Fishbein, MD, editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

In the late 1920s, the Mead Johnson company introduced Sobee, the first soy-based formula. Several years later, the company marketed Pablum, the first precooked fortified infant cereal. Pablum was a mixture of wheat, oats, corn, bone meal, wheat germ, alfalfa, and dried brewer's yeast fortified with minerals and vitamins.

The rise of proprietary formulas

Despite the introduction of proprietary infant formulas in the 1920s, most parents continued to use evaporated milk formula because it was easy to prepare and affordable. It was not until the 1950s that commercial formulas began to slowly gain acceptance (Figure 1 in the print edition, Adapted from Fomon SJ: Infant feeding in the 20th century: Formula and beikost. J Nutr 2001;131:409S).

It was not until the 1950s that commercial formulas began to slowly gain acceptance (Figure 1 in the print edition, Adapted from Fomon SJ: Infant feeding in the 20th century: Formula and beikost. J Nutr 2001;131:409S).

In the decades that followed, a variety of new formulas came on the market. Nutramigen, introduced in 1942, was the first protein hydrolysate infant formula. Ross Laboratories' Similac concentrate became available in 1951, and Mead Johnson's Enfamil (for "infant milk") was introduced in 1959. In that year, Ross first marketed Similac with iron. Iron-fortified formula was poorly accepted initially because of the widespread belief that iron fortification caused gastrointestinal disturbances such as diarrhea and constipation.

During the 1960s, commercial formulas grew in popularity, and by the mid-1970s they had all but replaced evaporated milk formulas as the "standard" for infant nutrition. During this time, the percentage of women who breastfed their newborn reached an all-time low (25%), in part because of the ease of use and low cost of commercial formula and a belief that formulas were "medically approved" to provide optimal nutrition for young infants (Figure 2 in the print edition, Adapted from Fomon SJ: Infant feeding in the 20th century: Formula and beikost. J Nutr 2001;131:409S).

J Nutr 2001;131:409S).

A major factor in the acceptance of commercial formulas was their use in hospitals to feed newborn infants during the 1960s and 1970s. To encourage acceptance, formula companies began to provide inexpensive or free formula to hospitals in ready-to-feed bottles, enabling the phasing out of hospital formula preparation rooms. Mothers who witnessed how well their newborns accepted these easily prepared formulas were often convinced to continue this practice at home. Moreover, although pediatricians did not dissuade mothers from nursing, it was not strongly encouraged, as it is today.

The modern era: Fine-tuning formulas

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition first made recommendations for vitamins and mineral levels for infant formulas in 1967. These recommendations have been revised periodically.6 (See "AAP's Committee on Nutrition: Infant formula and beyond,".) In 1969, the committee endorsed iron fortification of infant formula; in the years that followed, the incidence of iron deficiency anemia dropped strikingly. 7

7

In 1978 and 1979, 141 cases of hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis in infants, resulting from consumption of two soy formulas, Neo-Mull-Soy and Cho Free (produced by Syntex, Inc.), were reported to the Centers for Disease Control. This prompted the passage of the Infant Formula Act of 1980, which set maximum and minimum standards for many nutrients in formulas and mandated testing and manufacturing standards as well.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of nutrition research over the past several decades has been the introduction of specialty formulas and human milk modifiers used to feed premature and very low-birthweight infants. For term and near-term infants, formula manufacturers have continued to improve their "standard" formulas to more closely resemble breast milk. In 1997, Ross's Similac was reformulated to change the whey:casein ratio (then, 18%:82%) to 52%:48%, which more closely resembles that of human milk (70%:30%). The ratio of Mead Johnson's Enfamil is 60%:40%. Both Mead Johnson's and Ross's formulas contain added nucleotides in amounts similar to those in breast milk, and this year both companies have introduced formulas that contain long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Both Mead Johnson's and Ross's formulas contain added nucleotides in amounts similar to those in breast milk, and this year both companies have introduced formulas that contain long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Over the past few years, these two companies also have begun marketing "niche" formulas, including lactose-free formulas (both companies), a soy formula with dietary fiber to hasten recovery from gastroenteritis (Ross), and a formula with rice starch for babies with reflux (Mead Johnson).

Today's young infants are the beneficiaries of a long and complicated history of infant formula. While we continue to encourage mothers to breastfeed their infants, babies who are fed formula from birth or are weaned to formula from breast milk receive the best nutrition medical science has to offer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author thanks Virginia A. Mason for her assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Siberry GK (ed): Harriet Lane Handbook, ed 14. St. Louis, Mosby Year Book, 1996

Siberry GK (ed): Harriet Lane Handbook, ed 14. St. Louis, Mosby Year Book, 1996

2. Spaulding M: Nurturing Yesterday's Child: A Portrayal of the Drake Collection of Paediatric History. Philadelphia, BC Decker, 1991

3. Cone TE: History of American Pediatrics. Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1979

4. Apple RD: Mothers and Medicine: A Social History of Infant Feeding. Madison, Wis., University of Wisconsin Press, 1987

5. Marriot WM, Schoenthal L: An experimental study of the use of unsweetened evaporated milk for the preparation of infant feeding formulas. Arch Pediatr 1929;46:135

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition: Proposed changes in food and drug administration regulations concerning formula products and vitamin-mineral dietary supplements for infants. Pediatrics 1967;40:916

7. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition: Iron balance and requirements in infancy. Pediatrics 1969;43:134

Pediatrics 1969;43:134

DR. SCHUMAN is adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, N.H., and practices pediatrics at Hampshire Pediatrics, Manchester, N.H. He is a contributing editor for

Contemporary Pediatrics. He serves on the speakers' bureaus of Ross Laboratories and Mead Johnson.The pediatrician's infant formula trivia quiz

1. What percentage of infants in the US are breastfed at birth?

a. 85% b. 69.5% c. 25%

Answer: b. According to the most recent data, the 2001 Ross Mother's Survey (Ryan AS et al: Pediatrics 2002;110:1103), 69.5% of newborns in the US are breastfed at birth. That is significantly higher than the 50% recorded a decade ago.

2. What percentage of infants are breastfed at 6 months?

a. 50% b. 39% c. 32. 5%

5%

Answer: c. According to the 2001 Ross Mothers' Survey, 32.5% percent of infants are breastfed at 6 months.

3. Which formula manufacturer has the largest market share in the US?

a. Ross b. Mead Johnson c. Carnation

Answer: b. According the latest (2000) published information from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Mead Johnson holds 52% of the infant formula market, including 68% of the market from the federal Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutrition program. In 1994, Mead Johnson's market share was 27%. Ross has a 35% market share (down from 53% in 1994), and Carnation has 12% of the market. PBM products (such as Parents Choice, manufactured by Wyeth), has a 1% market share. Approximately 27 billion ounces of formula are consumed each year in this countryaccounting for about $2.9 billion in revenue for formula manufacturers. (Source: Oliveira V et al: Infant formula prices and availability: Final report to Congress. Economic Research Service, USDA 2001, www.ers.usda.gov/publications/efan02001/efan02001d.pdf )

Economic Research Service, USDA 2001, www.ers.usda.gov/publications/efan02001/efan02001d.pdf )

4. Which type of formula is most popular?

a. Powder b.. Ready-to-feed c. Concentrate

Answer: a. Powder. Sales of powdered formula rose from 42% in 1994 to 62% in 2000; sales of liquid concentrate declined from 42% to 27%. Powder is the most economical formula preparation.

5. Infants with diarrhea are often given Pedialyte (Ross) before they resume regular formula. When was Pedialyte introduced?

a. 1956 b. 1966 c. 1976

Answer: b. 1966

6. Where do parents purchase most infant formula?

a. Supermarkets b. Pharmacies c. Mass merchandisers (Walmart, Costco, etc.)

Answer: a. In 2000, 69% of formula in the US was purchased in supermarkets; 28% was bought from mass merchandisers; and 3%, from pharmacies.

In 2000, 69% of formula in the US was purchased in supermarkets; 28% was bought from mass merchandisers; and 3%, from pharmacies.

7. What percentage of formula sold in the US is milk-based?

a. 97% b. 87% c. 77%

Answer: c. 77%

8. Gerber introduced its own brand of infant formula in 1989 that vanished from store shelves in 1997.Who manufactured Gerber's formula?

a. Carnation b. Mead Johnson c. Wyeth

Answer: b. Mead Johnson

9. According to 2000 USDA data, which brand of milk-based powder is the most expensive?

a. PBM (Parents' Choice) b. Similac c. Enfamil

Answer: b. Similac (Ross). According to USDA data, the average cost of 26 reconstituted ounces in 2000 was $2. 63. The least expensive brand was PBM, manufactured by Wyeth: In 2000, the average cost of 26 reconstituted ounces was $1.56.

63. The least expensive brand was PBM, manufactured by Wyeth: In 2000, the average cost of 26 reconstituted ounces was $1.56.

10. Which brand of soy-based powder is the most expensive?

a. Prosobee b. PBM (Parents' Choice Soy) c. Isomil

Answer: a. Prosobee (Mead Johnson). According to USDA data, Prosobee cost $2.90 for 26 reconstituted ounces in 2000. The least expensive soy-based powder was PBM (Wyeth), which cost $1.61 for 26 reconstituted ounces in 2000.

AAP's Committee on Nutrition: Infant formula and beyond

The Committee on Nutrition of the American Academy of Pediatrics was established by the AAP's Executive Board on April 1, 1954. Its first chairman was Charles D. May, then chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at the College of Medicine, University of Iowa. Its charge was as follows:

"This Committee shall concern itself with standards for nutritional requirements, optimal practices, and the interpretation of current knowledge as these affect infants, children, and adolescents. "

"

The Committee on Nutrition initially published educational reports; it did not begin publishing policy statements until the mid-1960s. The committee provided invaluable assistance to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by defining nutritional requirements for infant formulas.Its 1967 recommendations for levels of nutrientsin infant formula was used by the FDA to createthe 1971 regulation establishing the minimum requirements for fat, protein, linoleic acid, and17 vitamins and minerals in formula. After an outbreak of chloride deficiency in infants fed certain formulas (see article), the Committee on Nutrition revised its recommendations regarding nutrient content.

The Infant Formula Act of 1980 gave the FDA authority to regulate the labeling of infant formula and establish quality control rules and regulations governing formula manufacturing. The act was revised in 1985, based on recommendations from the Committee on Nutrition, to include minimum concentrations of 29 nutrients and maximum concentrations of nine nutrients in infant formula.

The committee continues to play an important role in pediatric nutrition by issuing policy statements as new information becomes available and publishing the Pediatric Nutrition Handbook. Now in its fourth edition, the handbook provides pediatricians with information on a wide variety of nutrition topics. Recent policy statements from the committee have addressed iron fortification of infant formula (1979, 1989, 1999), the use of hypoallergenic infant formulas (2000), breastfeeding and the use of human milk (1997), soy-protein-based formulas (1998, 2001), and the use and misuse of fruit juice (2001).

Andrew Schuman. A concise history of infant formula (twists and turns included). Contemporary Pediatrics 2003;2:91.

Cap twist-off board | Lovevery

This activity is a fun way for your child to practice their fine motor skills, and also reuses disposable baby food pouches. Twisting caps to loosen and tighten them takes concentration and coordination, and can be done (and redone and redone) over and over again.

Here’s how to make a cap twist-off board:

- Collect and thoroughly wash out food pouches until you have enough for this activity—4 should be plenty to start, and 6-10 makes it even more fun. Even if you only have one lying around right now, it’s enough! If you don’t have any pouch lids, look for others that could be affixed to a board: plastic bottle tops, small jars that can be glued down, etc.

- Cut the tops off, leaving some of the plastic around them; get a flat piece of cardboard and cut a few holes, then poke the extra plastic from the pouch tops through and affix it to the underside with sturdy glue or tape. The sturdier you can connect them the better, as your child may test the structural integrity of your twist-off board!

- Play around with the spacing and the organization of the tops; you can arrange them in a grid, circle, line, or any other pattern.

- Show your child how to screw and unscrew the tops. Children vary immensely in their ability to twist, screw, and unscrew, so don’t be surprised if this part is a challenge.

If they get the cap all the way off, sticking it back on to screw in again may take a little assistance on your part.

If they get the cap all the way off, sticking it back on to screw in again may take a little assistance on your part. - For a different approach, tape the cardboard to the underside of a table or chair—twisting and untwisting something above their heads adds a new layer of challenging fun, and the caps come clattering to the ground when they twist all the way off. You can also make the board vertical by leaning it against (or taping it to) a wall.

Keep reading

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

6 tips for trimming your toddler’s nails

Having their nails cut is a little bit scary for your child. Here are some adjustments that might make the process a little easier for both of you.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Is your 1-year-old ready for logical consequences?

Logical consequences are about helping your toddler regulate their emotions and their body. They're meant as a reset—not punishment.

They're meant as a reset—not punishment.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

3 steps to setting toddler limits with empathy

Read our three steps to setting toddler limits with empathy and understand what empathetic boundaries teach children.

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

6 ways to build your toddler’s attention span

Giving your child opportunities to focus on a task uninterrupted and get into a “zone of concentration'' is an important part of the Montessori approach.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Why your toddler may need space instead of a hug

Some toddlers are less soothed by close physical contact than they were as babies. Learn what to do when a hug won't work.

Learn what to do when a hug won't work.

22 - 24 Months

25 - 27 Months

28 - 30 Months

31 - 33 Months

34 - 36 Months

Try this to raise your child’s emotional intelligence

Using specific and even complex words to describe how your child feels gives them a deeper, more nuanced understanding of their emotions.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

When it’s time to leave and your toddler won’t go

When children are enjoying an activity, they just want to keep doing it. Read our 6 steps to help your toddler transition.

Read our 6 steps to help your toddler transition.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

How to ease your separation anxiety

Separation anxiety doesn't happen only to children—it affects parents, too. Read 4 tips to help you deal with your separation anxiety.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Toddler tantrums: why they happen and how to handle them

All toddlers have temper tantrums. Learn the dos and don'ts to help you and your child through public and private meltdowns.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Making the most of your toddler’s fascination with cause and effect

Toddlers understand that they can make things happen with simple actions. Here are 4 ways to deepen their understanding of cause and effect.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

5 co-regulation tips to help your toddler manage their feelings

Co-regulation is the process of showing your toddler how to manage emotions by doing it together. Try these expert tips the next time your child gets upset.

Try these expert tips the next time your child gets upset.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

5 easy play tunnel games for toddlers

Learn why crawling is so important for toddlers and how to encourage it with simple play tunnel games.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Wish your toddler would focus? Try playing together first

Are you eager for your toddler to play longer with a toy? Learn what you can do to help them get the most out of their playthings.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Why it’s important to allow your toddler’s big emotions

Big feelings are a sign of your toddler's healthy social-emotional development. Learn three ways to help you and your child manage them.

Learn three ways to help you and your child manage them.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

6 phrases to say to your toddler instead of ‘Be careful!’

The occasional “Be careful!” isn’t harmful, but it’s better to give your child clear, explicit directions. Here are 6 phrases to try.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

When (and how) to transition your toddler from 2 naps to 1

Knowing when your toddler is ready to drop their morning nap can be tricky. Understand the signs to look for and the best ways to drop to one nap.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Secrets to building your toddler’s self-esteem

As your toddler becomes more independent, you have an opportunity to help them cultivate healthy self-esteem. Here are 4 ways to help your toddler develop it.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Why does my toddler hate certain clothes?

If your toddler dislikes certain clothes, it may be a sensory issue. Learn five simple adjustments from a pediatric occupational therapist.

22 - 24 Months

25 - 27 Months

28 - 30 Months

31 - 33 Months

34 - 36 Months

Best Montessori and learning toys for 2 year olds

The best toys for 2 year olds support emerging independence and sense of identity. They also give your child opportunities for fine and gross motor practice, problem-solving, practical life skills, and more.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

The best Montessori and learning toys for 1 year olds

At 12 months old, your toddler is more mobile and curious than ever. The best toys support mobility, fine motor skills, language, and independence. See our best Montessori toys for 1-year-olds.

The best toys support mobility, fine motor skills, language, and independence. See our best Montessori toys for 1-year-olds.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

25 - 27 Months

28 - 30 Months

31 - 33 Months

34 - 36 Months

What kind of chores are right for my child?

Children as young as 18 months can start taking on regular household responsibilities. These will be simple and straightforward, like wiping up spills or helping set the table, and will require modeling and patience from you.

0 - 12 Weeks

3 - 4 Months

5 - 6 Months

7 - 8 Months

9 - 10 Months

11 - 12 Months

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

25 - 27 Months

28 - 30 Months

31 - 33 Months

34 - 36 Months

Why wooden toys make the best playthings

Wooden toys are a staple of Montessori learning. They're durable, beautiful, and inspire wonder for a child's budding imagination.

They're durable, beautiful, and inspire wonder for a child's budding imagination.

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Updated Lovevery Play Kits featuring larger, more complex developmental Playthings

After play studies, weeks of in-home testing, and thousands of customer surveys, we are excited to announce our updated Play Kits for one-year-olds.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Dirty vs clean: a quick lesson in contrast

Your toddler’s brain loves to grapple with opposites. A great way to involve your toddler in learning about opposites is by exploring the idea of dirty vs clean

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Mess-Free water painting

This water painting activity boosts gross and fine motor skills and is incredibly simple. All you need are paint brushes and a bucket of water.

All you need are paint brushes and a bucket of water.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Cap twist-off board

Twisting caps to loosen and tighten them takes concentration and coordination, and can be done over and over again. This activity reuses disposable baby food pouches to allow your child to practice.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Pipe cleaners and Wiffle Balls

"Posting” is a term used to describe fitting objects into an opening of corresponding size. In this activity, colorful, bendable pipe cleaners fit into Wiffle balls for all kinds of posting fun.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Velcro dot craft sticks

This DIY craft activity has can be taken on car trips and stored easily for future use—and it supports multiple developmental skills as well.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Pop-up paper tunnels

In this activity, your child will push toy cars, trains, planes, and other small vehicles through DIY tunnels, creating a world of pretend play to get lost in.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

DIY Balloon Tennis

This simple DIY is a great source of entertainment and helps develop gross motor skills and hand-eye coordination. All it takes is a paper plate, popsicle sticks, and a balloon.

19 - 21 Months

22 - 24 Months

Toilet Paper Roll Crafts

Some of the best craft materials can be found in the recycling bin. Here are 3 crafts you can do with your toddler using toilet paper rolls.

Here are 3 crafts you can do with your toddler using toilet paper rolls.

19 - 21 Months

Welcome to The Realist Play Kit for months 19-21

Watch Lovevery CEO Jessica Rolph introduce the Realist Play Kit for months 19 to 11 of your toddler's life.

22 - 24 Months

Welcome to The Companion Play Kit for months 22-24

Watch Lovevery CEO Jessica Rolph introduce the CompanionPlay Kit for months 22 to 24 of your toddler's life.

22 - 24 Months

25 - 27 Months

3 easy pincer grasp activities for toddlers

The pincer grasp isn't just for babies. Toddlers need to continue strengthening this coordination and dexterity for future tasks.

Toddlers need to continue strengthening this coordination and dexterity for future tasks.

19 - 21 Months

Introducing the Montessori Animal Match game to your toddler

Lovevery CEO Jessica Rolph and Montessori Expert Jody Malterre demonstrate how the Montessori Animal Match game helps toddlers link 2D images with 3D figurines.

22 - 24 Months

Don’t buy that gorgeous wooden play kitchen just yet, by Lovevery CEO Jessica Rolph

Consider these fun and safe ways to include your toddler in your real kitchen before you buy a new toy kitchen.

19 - 21 Months

Clean up, clean up, everybody, everywhere

Giving your toddler opportunities to help with household tasks makes them feel independent and valuable. Try these ways to encourage your child to participate.

Try these ways to encourage your child to participate.

19 - 21 Months

Picture book project! 🌈 Preserving your toddler’s first words

This DIY project captures your child's first words and builds their vocabulary as their language develops.

19 - 21 Months

Kicking, biting, and hitting: understanding and responding to your toddler’s tantrums

Kicking, biting, and hitting are common all with toddlers, and knowing what to do can be hard—especially if you’re in public. Here's what you should know.

19 - 21 Months

The toddler game of who, what, where, why, how?

Introducing who, what, where, why, and how in little lessons empowers your toddler to begin explaining what interests them the most.

19 - 21 Months

We asked 4 professionals what they wished toddler parents would do more of

We asked some of our favorite early childhood, Montessori, and resilience experts to share some advice with us. Here are their top 10 tips.

19 - 21 Months

The magical teaching powers of words like ‘humongous’

Learn how to build your child's language skills and comprehension with plenty of rich vocabulary, back-and-forth conversations, narration, and repetition.

19 - 21 Months

8 ways toddlers start to talk between 18 and 24 months

Here are 8 ways your toddler is learning language right now, even if they're not saying much yet.

19 - 21 Months

The earlier, the better: math is already developing in your toddler’s brain

Neuroscientist Gillian Starkey shares tips for introducing your toddler to math and why it's beneficial to start now.

19 - 21 Months

5 ways to play the pom pom way

Pom poms are a fun way for your toddler to develop their fine motor skills. Try these ideas for at home or on the go.

19 - 21 Months

The Montessori activity you already have in your house

Develop your toddler's fine-motor skills and concentration in a fun new way with items you probably already have at home.

22 - 24 Months

Ice, ice, baby—try these easy science activities

Sensory exploration of colors, shapes, and textures with your child doesn't have to be complicated. Here are a few simple science activities for toddlers.

22 - 24 Months

4 funky ways to make music a part of your toddler’s life

Music is a great way for toddlers to express creativity. Lovevery provides 4 fresh ways to make music a part of your child's life.

22 - 24 Months

Is squashing bugs OK? 5 environmental lessons your toddler can learn now

Children react in various ways when they encounter bugs, but what should they do? Here are 5 environmental lessons your toddler can learn now.

22 - 24 Months

Make me a match—understanding your toddler’s matching skills

Matching images, objects, colors, and sound builds a toddler's pattern recognition and visual and short-term memory. Learn how matching skills progress.

22 - 24 Months

The better way to help your toddler learn colors

Lovevery shares the techniques discovered by Stanford University that pinpoint a new, effective way to teach young children about colors.

22 - 24 Months

A whole new era of pretend play just started

Learn how to support your todder's pretend play, which is based on their own lived experiences. Imagination play will come later.

Imagination play will come later.

22 - 24 Months

The pincer grasp is not just for babies

Learn why practicing the pincer grasp can help your child succeed in school and beyond by developing their fine motor skills and hand strength.

22 - 24 Months

Why labeling your toddler’s intense feelings can actually help calm them down

Dr. Dan Siegel "name it to tame it" philosophy helps children calm down by acknowleding and labeling their strong emotions.

19 - 21 Months

What should my toddler’s art look like right now?

More than anything, toddler art is a sensory exploration involving fine and gross motor movement. Here are the stages of toddler drawing development.

Here are the stages of toddler drawing development.

19 - 21 Months

4 signs toddlers understand language even if they aren’t talking much yet

Your toddler likely understands more than they can say. Here are 4 ways your toddler is communicating without words.

Igor Maltsev: Baby food from Jamie Oliver - Igor Maltsev - Health - Site materials - Snob

I have my own accounts with Jamie Oliver. No, of course, he is a fantastic guy, energetic, albeit lisping and white. It is not easy to manage to become a TV star with such an invoice. So kudos to him. He says that he tried to dispel the myth that the British do not know how and do not like to cook and therefore eat tastelessly and boringly. I don't know what this myth is - probably the British themselves spread it, so as not to jinx the Cumberland sausages and lamb roast, poured with mint sauce.

Moreover, he somehow strangely dispels the myth about English cuisine, planting Italian cuisine entirely on the islands. And, triple the price tag. I ate at his restaurant Fifteen, and more than once, to avoid unnecessary questions. Never been able to eat less than 80 pounds for two and 400 for four. At the same time, quite ordinary Italian-oriented food was served. And quite ordinary oil and super ordinary aceto balsamico, etc.

But I liked that young delinquents and guys who had served time in prison were plowing in his kitchen. Well, he made several million pounds from a TV program, books and recipes. The main thing in such cases is social responsibility.

And when I saw a lively discussion in the press five years ago about Jamie's decision to take over the huge school lunch market in Britain, I quite believed it - it looks like him. It turned out that he was pictorially surprised at the filth that they give to schoolchildren, and for a start he took one school - Kidbrooke (Greenwich) to work for a year.

He filmed everything that happened at school as part of a documentary film. And showed it on TV. As a result, the British government agreed to give £280 million for school lunches, spread over three years. Jamie himself was awarded the title of Most Inspiring Political Figure of 2005, and Tony Blair himself attributed the increase in budgetary funding for school meals to the popularity of the campaign launched by Oliver.

Gradually, Jamie's sponsored schools became more, but already in 2006 Jamie met with a sharp rebuff from the parents of the school in the town of Rowmarsh (South Yorkshire). They said that the two pieces of fruit and three pieces of vegetables that Oliver's plan is supplying his company to 1,100 students are a) not worth the money and b) worse than what you can buy in local stores. Parents defiantly bought hamburgers and other junk food and passed it over the school fence to the kids for the little blood to eat. One of the parents even said that Oliver's baby food is "absolute shit. "

"

However, this small demarche did not spoil the furrows of the TV star chef - by 2010 he was already supplying food to 80 schools, which are still labeled as a “pilot project”. Further, of course, there will be more schools. I understand that Oliver is haunted by the example of his beloved Italy, where since 2005 (what an amazing coincidence) the feeding of children in schools only with so-called organic food has been legislated.

It was within the framework of this "pilot project" that the famous "British scientists" throughout Russia tried to calculate the impact of healthy breakfasts on the level of education. It turned out that it was in these schools that the number of good students in English increased by 4.5%, and the number of excellent students - by 6%. The strangest thing is that Oliver's officially recognized healthy food did little to help children from low-income families, but helped children with richer backgrounds.

This is not particularly unusual - children from wealthy families quickly adapt to a change in their usual menu.

What was there before Oliver?

Burgers and chips, sausage rolls, turkey legs, fish sticks, chicken. For dessert - sweet corn and vanilla pudding, milkshake, fruit salad, choux pastry and "homemade" biscuit.

What do they have after Oliver?

"Proper" sausages (probably made by Jamie), mashed potatoes and peas, vanilla pudding, choux pastry. Chicken casserole with mushrooms, roast beef, fried potatoes, green beans with gravy, then a plate of fruit and choux pastry.

Can you see the difference between "before" and "after"? Well, I don't see it either.

Now Jamie is off to conquer America, which, as is known from the newspapers and speeches of Russian TV comedians, is decidedly mired in obesity.

Armed with the knowledge that his menu works well for students' academic success, he tries to do the same trick with American children who today eat salty chips, candy, snacks (presumably everything from candy bars to infinity) much more than in previous years.

Today, American children get a third of their daily calories from snacks, which, of course, leads to massive obesity, and most importantly, an increased risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, and other quite adult pleasures. These are the results of a study published in the March issue of the journal Health Affairs.

A group of scientists from the University of North Carolina studied the time-reversed eating patterns of today's American children and argue that many children from two to eighteen years old do not eat anything at all during the day except junk food.

So far, scientists advise limiting the consumption of snacks - no more than once a day for children over six years old, accompanying the ban with clear educational work. And before that age, do not give them candy and other junk at all. Plus - make sure that children always eat a few apple slices, carrots and other fruits and vegetables.

Well, now it's time for the successful socially responsible English millionaire Jamie Oliver to enter the American scene. He will save everyone. How the Beatles saved American rock culture.

He will save everyone. How the Beatles saved American rock culture.

What are we talking about in the future tense, if it has already begun? Jamie took as an experiment a school in "the fattest city in America" - Huntington, West Virginia. All this is being filmed as part of his new show Jamie Oliver's Food Revolution and has been airing on ABC since the end of March. He started with first graders. The first series already demonstrates the basic knowledge of the kids in the field of food consumption. The TV presenter asked to indicate which of the vegetables presented to him were beets, eggplant, potatoes, tomatoes. The first graders did not successfully identify any of them. In the next episode, Jamie walks into the school kitchen and wonders why kids get pizza for breakfast and chicken nuggets for lunch. To which the head of the catering department tells him that this food is approved on the basis of research by American scientists in the field of healthy nutrition. Oliver is shocked. He says to the camera: "Well, here it is, the same food that is killing America." In the following series - proposals for the nutrition of children in schools, which were formulated by the star chef himself.

He says to the camera: "Well, here it is, the same food that is killing America." In the following series - proposals for the nutrition of children in schools, which were formulated by the star chef himself.

So we understand that perhaps Jamie was just lucky in British schools, where children's grades improved in the very year he started feeding them breakfast. But in the case of the States, everything is different: the school with which he began the recovery of the American nation was terribly lucky.

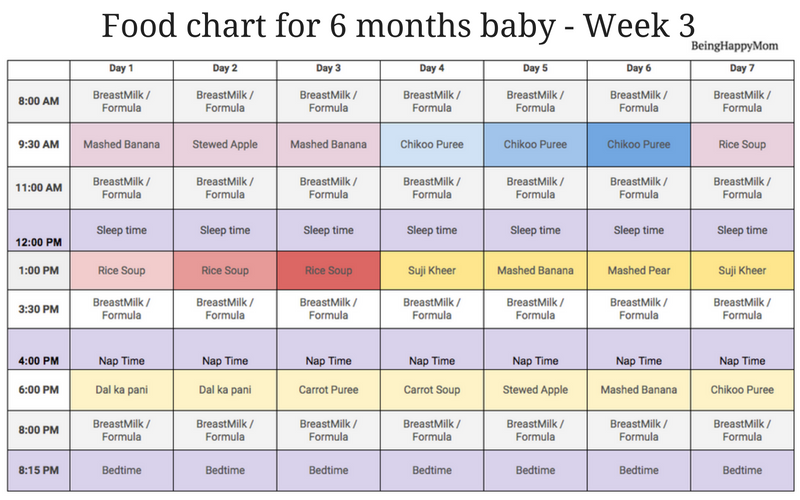

| As 1st complementary food , it is recommended to use vegetable puree made from one type of vegetable. This is done so that in the event of an allergic reaction, it would be easy to identify the allergen product. Potatoes, cabbages and marrows are the most harmless vegetables, which are most easily absorbed by the child's body. You should start with them. Each new puree should be given to the child for at least 2 weeks before moving on to the next one. When the child gets used to vegetable purees, you can alternate them or prepare vegetable mixtures. As soon as the 1st feeding is replaced with vegetable food, 2nd food is added – porridge made from gluten-free flour (rice, buckwheat or corn). Gluten (from the English. glue - "glue") is a high molecular weight protein found in some cereals: wheat, rye, barley and oats. If it is not tolerated, atrophy of the small intestine occurs, which leads to impaired intestinal absorption. During the first 2 weeks, the child is recommended to give 5% porridge, and after 1-2 weeks - 10% porridge. If the child is not recovering well or has loose stools, it is better to feed him first with cereals, and then with vegetable puree. At the age of 6-7 months 2-3 times a week the child can be given the egg yolk of a hard-boiled chicken egg. You need to start with a quarter of the yolk, pounded with breast milk. From 7-8 months the baby's menu should be introduced cottage cheese (starting with 5-10 g before the main feeding). Its amount should be gradually increased so that by the age of 1 year it is 50 g. From 7 months, the child is recommended to give meat puree, from 8-9months, it can be replaced with meatballs, and with 10-12 - steamed cutlets. Around the same time (7.5-8 months) the child's diet should include fermented milk products, as well as dairy products based on cow's milk with a low protein content. Earlier introduction of non-adapted milk mixtures can cause allergic conditions, acid-base imbalance, and also lead to a lag in physical development. C 8-9months 1-2 times a week it is recommended to replace a meat dish with a fish one. The child can be given bread soaked in complementary foods, wheat crackers or cookies. In 10-12 months the baby should be accustomed to grated cheese. As for oil, vegetable oil should already be included in the 1st complementary foods. Moreover, you need to start with 0.3-0.5 tsp, in order to gradually reach 1 tsp by the age of 1 year. Butter is recommended to be given to a child no earlier than 6 months. The baby should be weaned at about one year of age. However, it is possible to breastfeed him for longer, provided that this is accompanied by age-appropriate complementary foods, and the mother's lactation is maintained at the proper level. In this case, the child himself will determine the time when he should give up the breast. It is not recommended to continue to feed the child in this way for more than 3 years, as this may adversely affect the development of his personality. 1 shows an approximate scheme for the introduction of nutritional supplements and complementary foods to children in the first year of life.

Table 1 (end). Scheme for the introduction of nutritional supplements and complementary foods for children of the first year of life. Breastfeeding periods The 1st period, , during which the child adapts to the new environment, lasts 42 days. The most important of these are the first 2 weeks. This is a kind of rehabilitation after hard work - birth. These days a mother should be especially attentive to her newborn child and sensitively respond to his slightest needs. This is the only way to help a child form a favorable opinion about the world he has just entered. The most important response for a baby is attachment to the breast. That is why you should not keep the “set” hours, but feed the newborn as often as he wants: as a rule, every 1.5-2 hours. Moreover, feeding in this case acts as both a physiological and a psycho-emotional factor. It not only gives the child the food he needs, but also creates an atmosphere of security and comfort. The 2nd period, during which the child receives exclusively breast milk, lasts from the middle of the 2nd month to 6 months. First, the interval between daily feedings is 2-2.5 hours. The main applications are feedings before going to bed and before waking up. Their duration can be from 20 to 40 minutes. Other feedings are considered intermediate and usually last 2-3 times less. Night feedings at this time are 4:24.00, 4.00, 6.00 and 8.00. By the age of 3 months, the child himself establishes a "set" feeding schedule during the daytime: every 3 hours. It was him who not so long ago was recommended to mothers by all pediatricians from the very first days of a baby's life. At 3 months he becomes inquisitive, begins to react to sounds, objects around him and recognize familiar faces. Therefore, during feeding, he can release his chest and turn away, for example, to look at the one who has come, or to determine the source of a new sound for himself. During the 1st period, the mother should try to teach the baby not to turn his head during feeding. Otherwise, in the 2nd period, a child not accustomed to diligent sucking can injure the nipple, and his “unscrupulous” work during feeding can result in stagnation in the mammary glands of the mother. By the age of 6 months, the baby sleeps 2-3 times during the day, which means that the number of main feedings during the day is 4-6 applications. At this age, complementary foods are gradually added to breast milk, but the main food of the baby is still breast milk. 3rd period starts at 6 months and ends at 1 year. The number of feedings (both main and intermediate) may remain the same or change in the direction of decrease or increase. The baby begins to attach to one or the other breast, and does this in the process of 1 feeding (most often the main one). These are the makings of his future independence, which should not be interfered with. You should not resist the new postures that the child takes during feeding. During this period, the mother can already afford not to put her baby to the breast whenever he starts crying or expressing his displeasure in another way. It is enough just to take him in your arms, hug him, stroke him, kiss him, softly whisper something in his ear. If during the process of intermediate feeding the mother needs to get up for a while, then she can do this without waiting until the baby releases the breast. |

But pumpkin, tomatoes and green peas are recommended to be introduced into the baby's diet later, when his digestive system somewhat adapts to plant foods.

But pumpkin, tomatoes and green peas are recommended to be introduced into the baby's diet later, when his digestive system somewhat adapts to plant foods.

In this case, the mother must patiently wait for the baby to satisfy her curiosity and attach herself to the breast again. For him, this is a kind of game in which, turning away, he loses sight of his chest, and turning around, finds it in the same place. This gives him great joy. Otherwise, when the child, turning around, does not find the breast, he will experience slight stress and be very upset. Similar games are typical for intermediate feedings. Falling asleep, the baby sucks with concentration, almost not reacting to extraneous stimuli.

In this case, the mother must patiently wait for the baby to satisfy her curiosity and attach herself to the breast again. For him, this is a kind of game in which, turning away, he loses sight of his chest, and turning around, finds it in the same place. This gives him great joy. Otherwise, when the child, turning around, does not find the breast, he will experience slight stress and be very upset. Similar games are typical for intermediate feedings. Falling asleep, the baby sucks with concentration, almost not reacting to extraneous stimuli.  So many intermediate feedings. At night, the child still eats 3-4 times.

So many intermediate feedings. At night, the child still eats 3-4 times.