Baby cramping after feed

Cramps in babies: the causes and what you can do

What are cramps and how do they occur?

Just as in adults, abdominal cramp in babies is caused by sudden contractions in the intestines. Usually, a baby who's experiencing cramp will start to cry around 15 minutes to 45 minutes after feeding. They'll often stretch their body or stretch and relax their legs. You can also tell if a baby is suffering abdominal cramp as they'll have a red face and clenched fists.

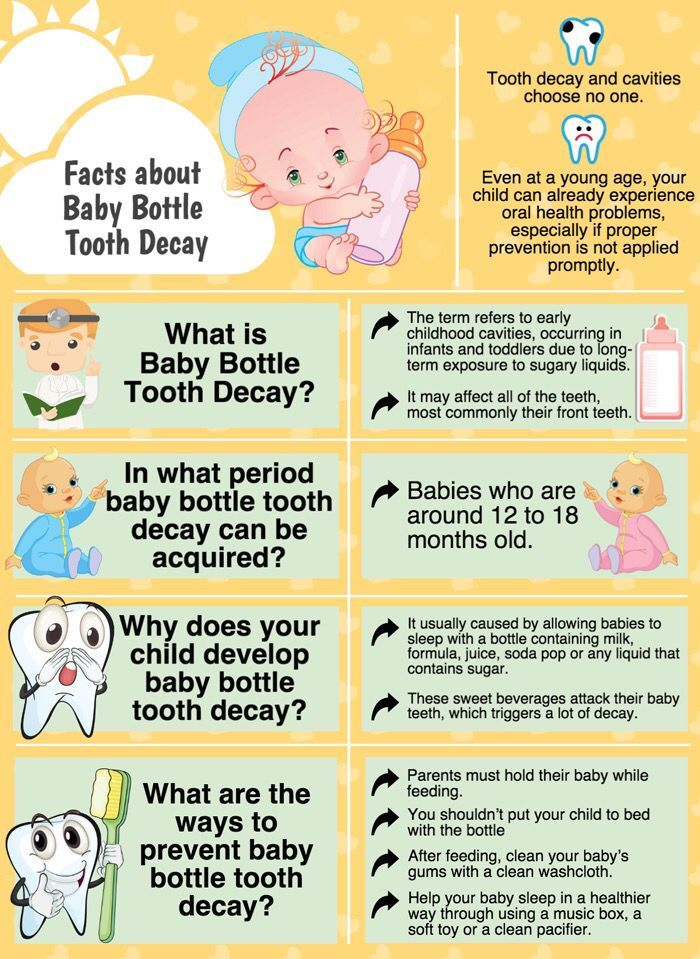

We don't completely know the origins of abdominal cramps in babies. In general, we assume that it's connected to the intestinal system and growing accumstomed to new types of food. Furthermore, cramps can also have a medical cause in some cases, for example, a diagnosed allergy to cow's milk. Fortunately, a cow's milk allergy is relatively rare in infants (2 to 3%), but if you think your little one may be is allergic to cow's milk, it's always advisable you to consult your family doctor.

When will a baby suffer from cramps?

A baby will often show symptoms at two weeks old. Abdominal cramps usually peak around the sixth week when your baby is often starting to drink more. This means the intestines have to work harder. Cramps can start during breastfeeding and bottle feeding. Every baby will be different in terms of when these craps stop, but in general the (worst) cramps are over when a child reaches four months old. By this time, your baby's bowels have got used to their diet and they have developed a better tolerance.

Relieving abdominal cramp: What can you do?

Fortunately, you don't have to stand idly by when your baby has cramps. Although this is part of a baby's development, there are ways to relieve abdominal cramp. You can start by looking at you baby's diet. Also, the speed you little one drinks can have an affect on the severity of the cramps. A hungry baby often tends to drink too quickly, causing them to swallow too much air. Try to encourage your baby to drink in a calm manner. If you're bottle feeding your baby and they're suffering from cramp, you could try another type of bottle or teat to reduce the amount of air your baby ingests. If this doesn't work, you could talk to your doctor or child health clinic about whether a different type of diet may be better.

If this doesn't work, you could talk to your doctor or child health clinic about whether a different type of diet may be better.

In addition to dietary considerations,, you can try various other tactics to reduce your baby's cramp:

Baby massage

Feeling your touch will calm your baby down. Make sure your hands are warm and use a little oil, making clockwise circular movements over your baby's tummy. This is the direction of the flow of the colon. Regular massage can relieve cramps. What's more, it can help to strengthen the mother-baby bond.

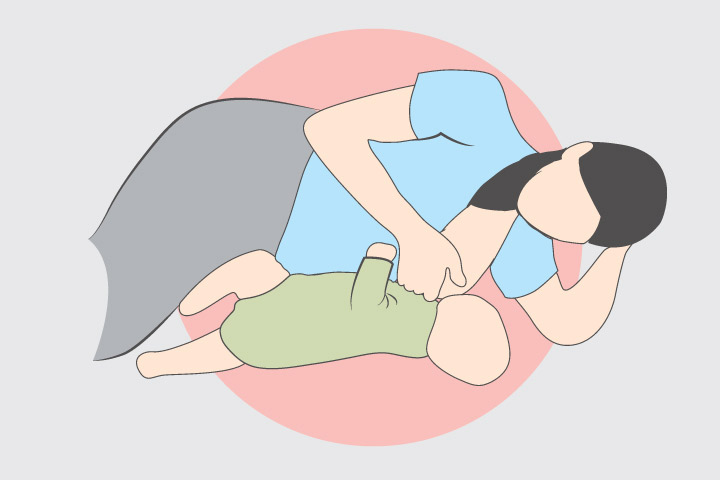

'Cycling' with the legs

Another way to release trapped wind is to get your baby to cycle with their legs. Take hold of your little one's legs and make circular movements as though your baby were cycling. This movement helps your baby to release wind and will relieve the worst of the cramp.

Carrying your baby in a sling

A baby with cramps and crying a lot can feel more secure in a sling. By being close to you will help your baby to feel safe. The cramps won't disappear immediately, but your baby will feel more comfortable because you're holding them close to you. A sling is ideal for little ones. The fabric is pleasantly soft and won't irritate the skin. A carry cot is designed for slightly older children.

The cramps won't disappear immediately, but your baby will feel more comfortable because you're holding them close to you. A sling is ideal for little ones. The fabric is pleasantly soft and won't irritate the skin. A carry cot is designed for slightly older children.

Laying a warm bottle on a baby's tummy

A warm bottle will feel nice if your baby is experiencing stomach cramp. You can also get special heat pads and hot water bottles for babies; these are safe and easy to heat up, providing the little extra warmth for your little one.

The information in this article has been carefully compiled and is intended to support young parents who are dealing with abdominal cramps in their little ones. Every child is different, which is why we always advise you to contact your family doctor or consultant if the problem is severe and/or persistent. These experts will be familiar with the individual situation regadring your child. Therefore, they're in the ideal position to decide if further investigation is required.

About Kabrita

The Kabrita Goat's Milk Feeding Bottle is a Dutch product and combines mild Dutch goat milk with the latest in nutrition, according to the most recent scientific insights. This leads to a full-fledged bottle formula, providing all the vital nutrients in a mild, gentle solution.

Would you like to keep in touch with the latest Kabrita news? If so, follow us on Facebook.

Baby Crying After Feeding: What Should You Do?

Did you imagine watching your new bundle of joy gently slip off to sleep in your arms while eating? Is your reality a screaming baby who can’t seem to get comfortable after feedings?

You’re not alone; it happens more frequently than you think. As moms, we’ve dealt with this ourselves. And as medical practitioners, we’ve seen plenty of parents with the same issue.

There are several reasons your baby might be feeling discomfort after feeding. We’ll look at some of the main causes of why your baby cries after feeding, and we’ll share some proven techniques you can use to make your baby more comfortable and your evenings calmer.

Why Do Babies Cry After Feeding?

If you’re dealing with an inconsolable child after feedings, you may have noticed some of the following symptoms of abdominal discomfort:

- Crying: Babies seem to experience more discomfort during the evening hours. If you’ve heard the cry before, you know it’s unmistakably a cry of pain. An urgency and intensity suggest it’s more than just complaining.

- Pulling up or extending their legs: Is your baby bringing their knees up to their chest or rigidly extending their legs? They are likely experiencing abdominal pain.

- Distended bellies: Most post-feeding discomfort can be linked to excessive gas in the baby’s system. If it’s trapped in their digestive system, it may lead to a hardened or swollen tummy. Their crying may be exacerbating the discomfort they’re already experiencing.

There are many possible causes of your baby’s discomfort. While this is not an exhaustive list, we’ll talk about some of the main sources of digestive discomfort in young babies.

1. Colic

Perhaps you’ve heard a baby referred to as colicky. Your pediatrician may have even given you the diagnosis. This designation came about after a pediatrician’s study on extremely fussy children and has been around for decades.

Having a colicky baby basically means you have a baby who cries — a lot. You can expect a baby with colic to cry at least three hours a day for at least three days a week (1). Using this definition, nearly a quarter of all infants will experience colic.

The good news is that 50% of babies with colic outgrow the condition by the time they’re three months old. By the time your baby reaches nine months old, there’s a 90% chance they’ll have outgrown the colic.

There’s usually no discernible cause for colic. But it’s clear your baby is uncomfortable. This discomfort is typically linked to the digestive system and follows feedings.

You may need to hold your colicky baby more often and provide lots of comfort. While it can be nerve-wracking and frustrating, having a colicky baby doesn’t mean your baby is unhealthy.

2. Acid Reflux

Also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), acid reflux is a common cause of post-feeding discomfort. It can be upsetting to hear your baby is experiencing reflux. But reflux isn’t uncommon; it affects up to 50% of babies during the first few months of life.

If your child is suffering from GERD, there may be additional accompanying symptoms, like difficulty gaining or maintaining weight. Children with GERD frequently spit up and may even experience aggressive vomiting (2).

When your child is experiencing acid reflux, it’s usually because the gastrointestinal system is not working properly. If the difficulty your baby is experiencing is related to an immature digestive system, a child may outgrow GERD. When this happens — as it does for about 95% of children — it usually does so by their first birthday.

There’s also a remote possibility your baby will not outgrow GERD. If this is the case, your doctor can help you create an ongoing treatment plan to support your child’s needs. If you suspect your child has GERD, you should make an appointment with a pediatric gastroenterologist to discuss your concerns.

3. Gas

Another common reason babies cry after feeding has to do with gas. Babies’ bodies are still developing their basic skills. A baby who swallows too much air during feedings may not be able to process the extra gas easily.

This leads to pressure and distension and can cause crying and extreme discomfort after meals. It may not be possible to keep your baby from taking in too much air during feedings. However, there are some things you can do to keep air intake to a minimum:

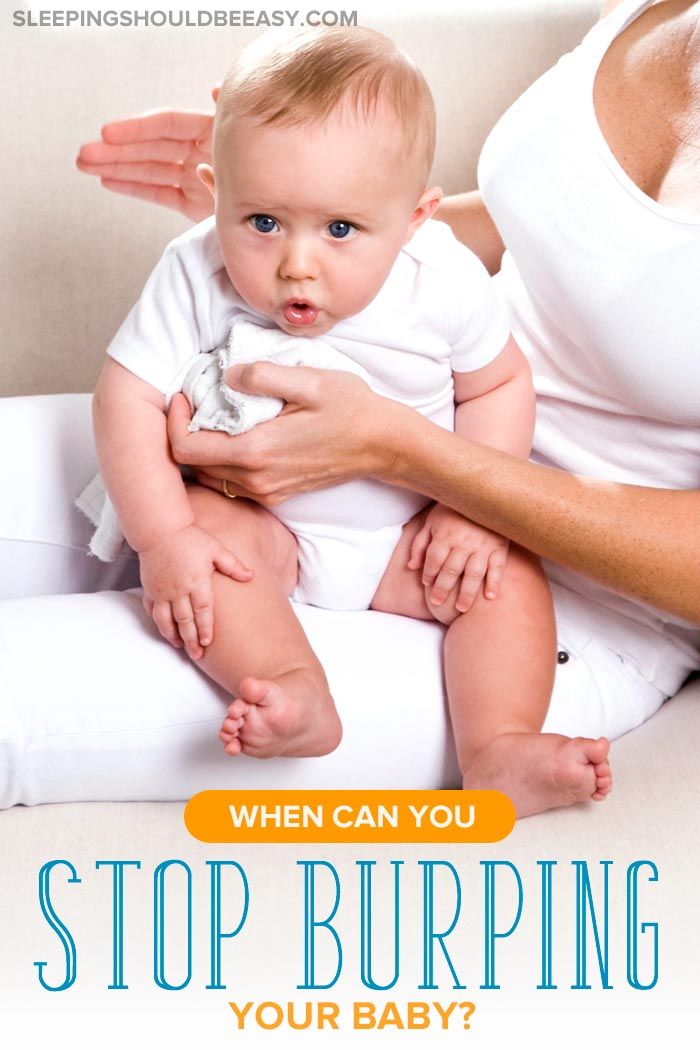

- Frequently burp your baby: Burping can help remove some of the excess air from your baby’s system and leave them feeling more comfortable.

To successfully burp your baby, hold them upright, supporting their head well, and pat or rub their back. Some babies seem to burp a lot, while others might have one good burp per feeding.

To successfully burp your baby, hold them upright, supporting their head well, and pat or rub their back. Some babies seem to burp a lot, while others might have one good burp per feeding. - Feed in a more upright position: Keep your baby upright for at least 20 to 30 minutes after meals to reduce gas discomfort. If your little one is uncomfortable during sleep, you can also try an inclined mattress, following safe sleep guidelines (3).

- Cycle your baby’s legs: If your baby is visibly uncomfortable, you can lie them on their back and cycle their legs as though they’re riding a bike. This can help push the air through their system and provide them with some relief.

- Try to catch the crying early: It can be tempting to let your baby work through the crying and get to sleep. If it’s likely your child won’t stop, intercept the crying as soon as possible. Crying usually involves gulping air, which will lead to more gas — and more crying.

- Don’t put your baby to sleep directly after a large meal: We all know it’s best for your baby to sleep on their back. But putting a baby down on their back with a full stomach can be a recipe for discomfort. Hold your little one for 20 minutes post-feeding, even if they’re already asleep.

These approaches are great whether you’re nursing or formula feeding. However, there are some specific things you’ll want to look out for, depending on how you feed.

Nursing

- Pay attention to how you eat: What you eat directly impacts your breast milk. Certain foods, including broccoli, beans, and onions, are notoriously difficult for your baby to break down. If you notice gas is especially bad for your baby after you eat a particular type of food, you can limit it in your diet.

- Food sensitivity: Something in your diet may be making your baby fussy. The most common culprits are dairy and caffeine. Usually, there are additional symptoms.

Keeping a food journal may help you pinpoint the offending item so you can eliminate it from your diet.

Keeping a food journal may help you pinpoint the offending item so you can eliminate it from your diet. - Nurse your baby in positions that keep their head above their stomach: This will help limit the amount of air intake and encourage digestion.

- Get rid of the excess gas: Plan on burping your baby before switching sides and after feeding.

Bottle Feeding

- Pay attention to the bottle nipple you’re using: If your bottle nipple releases fluid more quickly than your baby can comfortably eat, they will guzzle their meal. This leads to an increase in air intake and plenty of gas. Using a slow-flow nipple can help avoid this problem.

- Position your bottle properly: Make sure your bottle is tilted enough to allow the milk to cover the nipple completely. This will help prevent your baby from sucking in the air that’s in the bottle along with their meal.

- Force out the extra air: Expect to burp your baby after every ounce of milk or formula is consumed.

Gas can be highly uncomfortable for your little one. Following these tips will help you mitigate gas and discomfort for your baby.

4. Food Sensitivities

It’s possible that some of your child’s crying after eating is related to an intolerance or allergy.

Everything you consume is passed on to your child in your milk. Some foods — like dairy and eggs — are frequently associated with food sensitivities (4).

If you’re nursing, the best way to determine what’s agitating your child is by charting your food intake. Keep a food journal; you may be surprised at where correlations begin to appear.

Early on, my youngest was inconsolable after the last meal of the day — just when the time came to settle into sleep.

The common link to the discomfort? Spicy food and cheese during my dinner. I cut back on those, and my baby was happier for it.

We were fortunate our baby was only intolerant of these foods and didn’t have a true allergy. Sometimes a young system has difficulty handling certain foods. If your child has a true allergy, you’ll notice more symptoms than abdominal distress.

Be on the lookout for hives, skin rashes, vomiting, diarrhea, difficulty breathing, and any face or tongue swelling (5). If you suspect your child has an allergy, you should consult your pediatrician immediately. And if your little one is struggling with breathing after eating, call 911.

When starting solids, always introduce one new food at a time to your little one to determine what might have caused the response.

Formula feeding your baby? If you notice signs of a food allergy before introducing solid foods, your baby may be allergic to the formula (most commonly the cow’s milk protein). If you think this might be the case, work closely with your pediatrician to determine a suitable alternative formula.

Other Reasons For Crying After Eating

Many causes of post-feeding crying come back to the digestive process. They aren’t the only reasons, though. Some other things may cause your baby to cry.

5. Teething

Most babies will begin teething between 4 and 6 months of age. This doesn’t guarantee the teeth will show up shortly afterward, though. Some babies could go through several months of teething before the teeth break through the gums.

Unfortunately, your child will likely experience inflammation and extreme discomfort in the mouth and gums during this time. This can make even usually benign experiences, like nursing or bottle-feeding, incredibly painful.

If your baby is experiencing teething-related pain, you can help by numbing their gums with cool water before feeding. Just dip your thumb in water and rub directly onto the gums (6). Or let them chew on a washcloth that has been wet and then slightly frozen.

Other pain management approaches can include numbing oral medications and anti-inflammatories (though you’ll want to ask your baby’s doctor before using these). You’ll also want to provide plenty of opportunities for your baby to practice gnawing on things. This can help relieve the pressure, encouraging teeth to break through a little more quickly.

6. Thrush

Babies can experience an overgrowth of yeast in their mouths (7). While Candida, a parasitic fungus, is normally present in your body and in your baby’s mouth, excess yeast can be a problem. It’s extremely uncomfortable and may impact your baby’s ability to eat properly.

Excess amounts of yeast frequently happen after a course of antibiotics. Antibiotics will kill off the bad bacteria, but they don’t discriminate. This means they may also kill off good bacteria, leaving an imbalance that can lead to thrush.

Thrush is usually a visible condition. If you suspect your baby has thrush, look inside their mouth. If thrush is present, you’ll see filmy white patches that may look like milk. If the patch doesn’t come away with a swipe from your finger, you’re looking at thrush.

If thrush is present, you’ll see filmy white patches that may look like milk. If the patch doesn’t come away with a swipe from your finger, you’re looking at thrush.

If your baby has thrush, make an appointment with your pediatrician. A simple course of prescription antifungal medication will help clean up the condition.

Yeast is quite persistent. If you’re dealing with thrush, plan on sterilizing every plastic nipple or pacifier you own to prevent recontamination. Nursing? You’ll need to be treated for thrush as well — or you will simply pass the infection back and forth between you and your baby.

Feedback: Was This Article Helpful?

Thank You For Your Feedback!

Thank You For Your Feedback!

What Did You Like?

What Went Wrong?

Convulsive syndrome in children - causes of convulsions, symptoms, methods of prevention

Convulsive syndrome is a non-specific reaction of the child's body to external and internal stimuli, characterized by sudden attacks of involuntary muscle contractions. The smaller the child, the more convulsive readiness he has. This is due to the immaturity of some structures of the brain and nerve fibers, the high degree of permeability of the blood-brain barrier and the tendency to generalize any processes, as well as some other reasons.

The smaller the child, the more convulsive readiness he has. This is due to the immaturity of some structures of the brain and nerve fibers, the high degree of permeability of the blood-brain barrier and the tendency to generalize any processes, as well as some other reasons.

Reasons

All causes of seizures can be divided into epileptic (epilepsy) and non-epileptic.

Non-epileptic:

- Spasmophilia.

- Overheating.

- Encephalitis, meningitis, trauma and brain infections.

- Toxoplasmosis.

- Metabolic disorders, primarily potassium and calcium metabolism, for one reason or another.

- For newborns - hemolytic disease, congenital lesions of the nervous system, asphyxia.

- Various hormonal disorders.

- In acute infectious diseases, especially with a rise in temperature to febrile numbers.

- Intoxication and poisoning.

- Hereditary metabolic diseases.

- Pathologies of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic systems.

Symptoms

- Tonic convulsions (spasm-muscle tension).

- Pose with the upper limbs bent at all joints, the lower limbs extended and the head thrown back.

- Respiration and pulse are slow. Contact with the outside world is lost or significantly weakened.

- Clonic convulsions (involuntary muscle twitching).

The diagnosis of convulsive syndrome in children is made on the basis of the clinic, which in most cases does not cause difficulties. After making this diagnosis, it is necessary to clarify the nature of the convulsive syndrome, for which the anamnesis of the life and illness of the child, x-ray examination of the skull, echoencephalography, electroencephalography, angiography and other methods can be used. Laboratory tests can be quite revealing.

Prevention

Febrile convulsions (at high body temperature, above 38 C) usually stop with age. To prevent their recurrence, severe hyperthermia should not be allowed if an infectious disease occurs in a child. The risk of transformation of febrile seizures into epileptic seizures is 2-10%.

To prevent their recurrence, severe hyperthermia should not be allowed if an infectious disease occurs in a child. The risk of transformation of febrile seizures into epileptic seizures is 2-10%.

In other cases, the prevention of convulsive syndrome in children includes the prevention of perinatal pathology of the fetus, the treatment of the underlying disease, and observation by children's specialists. If the convulsive syndrome in children does not disappear after the cessation of the underlying disease, it can be assumed that the child has developed epilepsy.

More about pediatric neurology at the YugMed clinic

By leaving your personal data, you give your voluntary consent to the processing of your personal data. Personal data refers to any information relating to you as a subject of personal data (name, date of birth, city of residence, address, contact phone number, email address, occupation, etc.). Your consent extends to the implementation by the Limited Liability Company Research and Production Association "Volgograd Center for Disease Prevention "YugMed" of any actions in relation to your personal data that may be necessary for the collection, systematization, storage, clarification (updating, changing), processing (for example, sending letters or making calls), etc. subject to current legislation. Consent to the processing of personal data is given without a time limit, but can be withdrawn by you (it is enough to inform the Limited Liability Company Scientific and Production Association "Volgograd Center for Disease Prevention" YugMed "). By sending your personal data to the Limited Liability Company Research and Production Association "Volgograd Center for Disease Prevention" YugMed ", you confirm that you are familiar with the rights and obligations in accordance with the Federal Law "On Personal Data".

subject to current legislation. Consent to the processing of personal data is given without a time limit, but can be withdrawn by you (it is enough to inform the Limited Liability Company Scientific and Production Association "Volgograd Center for Disease Prevention" YugMed "). By sending your personal data to the Limited Liability Company Research and Production Association "Volgograd Center for Disease Prevention" YugMed ", you confirm that you are familiar with the rights and obligations in accordance with the Federal Law "On Personal Data".

Convulsive syndrome, useful articles of the medical clinic Neuro-Med

Convulsive syndrome

In children of the first year of life, convulsions are observed in various diseases of the nervous system. They may appear against the background of already existing neurological disorders and delayed psychomotor development, or appear as the first symptom indicating brain damage. The clinical picture of the convulsive syndrome depends both on the nature of the disease and on the age of the child. In newborns, convulsions often begin with local twitches of facial muscles, eyes, then they spread to the arm, leg on the same side and (or) move to the opposite. Clonic twitches may follow randomly from one part of the body to another. Such roads are called generalized fragmentary, as they represent a fragment of generalized convulsions [Rose A. L., Lambroso C. T.. 1970; Lacy J. R., Penry J. K., 1976].

In newborns, convulsions often begin with local twitches of facial muscles, eyes, then they spread to the arm, leg on the same side and (or) move to the opposite. Clonic twitches may follow randomly from one part of the body to another. Such roads are called generalized fragmentary, as they represent a fragment of generalized convulsions [Rose A. L., Lambroso C. T.. 1970; Lacy J. R., Penry J. K., 1976].

Newborns may also have focal clonic seizures affecting one half of the body. Sometimes they resemble Jackson's or proceed in the form of adversive turns of the head, eyes, tonic abduction of the hands in the direction of turning the head (ASTR type), opercular paroxysms (grimaces, sucking, chewing, smacking). The motor component of the seizure is often accompanied by vasomotor disorders in the form of pallor, cyanosis, redness of the face, salivation. Less often, myoclonic-type convulsions are observed in newborns, which are characterized by single or frequent twitches of the upper or lower extremities with a tendency to bend them. They can also be manifested by general shuddering followed by a large-scale tremor of the hands. Sometimes these convulsions are accompanied by screams, vegetative-vascular disorders. In mild cases, the abnormal movements that occur with seizures can be mistaken for spontaneous neonatal movements and miss the true onset of the seizure. The cause of convulsive syndrome in the neonatal period is often metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hyperbilirubinemia, pyridoxine dependence), brain development anomalies, hypoxia, intracranial birth trauma, less often neuroinfections (meningitis, encephalitis). Some early forms of hereditary metabolic disorders of amino acids (leucinosis, hypervalemia, argininemia, histidinemia, isovaleric acidemia, phenylketonuria), carbohydrates (galactosemia, glycogenosis), lipids (Norman-Wood and Norman-Landing diseases, Gaucher disease), vitamins (methylmalonic aciduria, Lee's disease, hyperglycinemia), occurring with acute development of neurological symptoms after birth, are also accompanied by a convulsive syndrome.

They can also be manifested by general shuddering followed by a large-scale tremor of the hands. Sometimes these convulsions are accompanied by screams, vegetative-vascular disorders. In mild cases, the abnormal movements that occur with seizures can be mistaken for spontaneous neonatal movements and miss the true onset of the seizure. The cause of convulsive syndrome in the neonatal period is often metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hyperbilirubinemia, pyridoxine dependence), brain development anomalies, hypoxia, intracranial birth trauma, less often neuroinfections (meningitis, encephalitis). Some early forms of hereditary metabolic disorders of amino acids (leucinosis, hypervalemia, argininemia, histidinemia, isovaleric acidemia, phenylketonuria), carbohydrates (galactosemia, glycogenosis), lipids (Norman-Wood and Norman-Landing diseases, Gaucher disease), vitamins (methylmalonic aciduria, Lee's disease, hyperglycinemia), occurring with acute development of neurological symptoms after birth, are also accompanied by a convulsive syndrome. In infants, unlike newborns, the motor component of the convulsive syndrome becomes more distinct. With generalized convulsions, a tendency to alternating tonic and clonic phases can already be noted, but it still remains mild compared to older children. The structure of the seizure is dominated by the tonic component, often convulsions (accompanied by vegetative symptoms (pain in vomiting, vomiting, fever). Involuntary urination is rarely observed. After the seizure, the child is often agitated, but may be lethargic, drowsy. clonic twitches of facial muscles, muscles of the tongue, distal limbs, turning of the head and eyes to the side.0005

In infants, unlike newborns, the motor component of the convulsive syndrome becomes more distinct. With generalized convulsions, a tendency to alternating tonic and clonic phases can already be noted, but it still remains mild compared to older children. The structure of the seizure is dominated by the tonic component, often convulsions (accompanied by vegetative symptoms (pain in vomiting, vomiting, fever). Involuntary urination is rarely observed. After the seizure, the child is often agitated, but may be lethargic, drowsy. clonic twitches of facial muscles, muscles of the tongue, distal limbs, turning of the head and eyes to the side.0005

The convulsive syndrome can also proceed according to the type of absences, which are characterized by a short stop of gaze. Sometimes at the moment of a seizure there are so-called motor automatisms in the form of sucking, chewing movements, smacking. The attack is often accompanied by vascular disorders and slight abduction towards the eyeballs. It should be noted that absences in infants are observed much less frequently than other types of seizures.

It should be noted that absences in infants are observed much less frequently than other types of seizures.

Infants are characterized by myoclonic seizures (infantile spasms) [Jeavons P. M. Bower B. D., Dimitracoudi M., 1973]. In children older than a year, seizures are rare. Due to the fact that convulsive seizures of this type have a malignant course and cause a severe delay in psychomotor development, it is necessary to dwell on them in more detail. Small propulsive seizures proceed in the form of bilateral symmetrical muscle contraction, as a result of which the trunk and limbs suddenly bend ("Salaam's seizures").

With extensor spasm, the head and trunk are sharply extended, arms and legs are abducted. Along with the classical clinical picture, there may be partial forms - general shudders, nods, head turns, flexion and extension of the arms and legs, sometimes a predominant contraction of the muscles of one side of the body is observed. A feature of small seizures is their tendency to seriality. Their frequency per day ranges from single to several hundred and more. Loss of consciousness is short-lived. Convulsions may be accompanied by a scream, a grimace of a smile, dilated pupils, nystagmus, rolling the eyes, trembling of the eyelids, and vascular disorders. There are seizures more often before falling asleep or after waking up.

Their frequency per day ranges from single to several hundred and more. Loss of consciousness is short-lived. Convulsions may be accompanied by a scream, a grimace of a smile, dilated pupils, nystagmus, rolling the eyes, trembling of the eyelids, and vascular disorders. There are seizures more often before falling asleep or after waking up.

In infancy, the cause of convulsive syndroitis can be organic lesions of the nervous system due to pre- and perinatal pathology, hereditary metabolic diseases, phakomatoses, leukodystrophy, neuroinfections, post-vaccination complications. In the first year of life, febrile and affective-respiratory convulsions are also often observed.

Febrile convulsions occur in acute respiratory infections: influenza, otitis media, pneumonia. These are usually typical generalized or local tonic-clonic convulsions that occur at the height of fever. Most often, febrile convulsions are single, sometimes repeated for 1-2 days. The risk of recurrent febrile paroxysm increases with the early onset of a primary seizure, its recurrence and an unfavorable neurological background [Aicardi J. C., Chevrie J. J., 1977; Nelson K. W., Ellenberg J. H. 1978].

C., Chevrie J. J., 1977; Nelson K. W., Ellenberg J. H. 1978].

Affective-respiratory convulsions are more often observed in children with increased excitability at the age of 7-12 months. Convulsions, as a rule, come after a negative emotional reaction to a strong sudden pain, fear. The child begins to scream loudly, then the breath is held while inhaling, the child turns blue, then turns pale, throws his head back, loses consciousness for a few seconds. At the same time, muscle hypotonia or, conversely, tonic muscle tension is noted. Following this, as a result of cerebral hypoxia, a generalized tonic-clonic seizure may develop. If the attention of the child is switched before the moment of loss of consciousness, the development of paroxysm can be interrupted.

The diagnosis of convulsive syndrome in children of the first year of life, especially in newborns, presents certain difficulties. This is due to the atypical course, abortion and short duration of paroxysms. Sometimes convulsions are mistaken for normal movements of the child and are diagnosed only when they become deployed and the child loses consciousness. At the same time, convulsions are sometimes referred to as pathological motor reactions of non-convulsive genesis (athetoid movements of the hands and forearms, spontaneous Moro reflex, asymmetric cervico-tonic reflex, contraction of individual facial muscles, grimacing, tremor of the tongue, sweeping hand movements such as hemibalism, hand tremor, etc. .). Sometimes "dystonic attacks" are taken for tonic convulsions, in which there is a sudden increase in muscle tone due to the influence of tonic cervical and labyrinth reflexes. Unlike convulsive syndrome in dystonic attacks, the child does not lose consciousness, and muscle tone can be reduced by giving the child a reflex-prohibiting position. In these cases, there are no EEG changes characteristic of the convulsive syndrome.

At the same time, convulsions are sometimes referred to as pathological motor reactions of non-convulsive genesis (athetoid movements of the hands and forearms, spontaneous Moro reflex, asymmetric cervico-tonic reflex, contraction of individual facial muscles, grimacing, tremor of the tongue, sweeping hand movements such as hemibalism, hand tremor, etc. .). Sometimes "dystonic attacks" are taken for tonic convulsions, in which there is a sudden increase in muscle tone due to the influence of tonic cervical and labyrinth reflexes. Unlike convulsive syndrome in dystonic attacks, the child does not lose consciousness, and muscle tone can be reduced by giving the child a reflex-prohibiting position. In these cases, there are no EEG changes characteristic of the convulsive syndrome.

When a convulsive syndrome occurs in a newborn, a thorough biochemical study should be carried out: blood and urine for the content of calcium, potassium, sodium, phosphorus, glucose, pyridoxine, amino acids, a lumbar puncture should be made to exclude subarachnoid hemorrhage, purulent meningitis. If convulsions first occur in infancy, then along with the above studies, an EEG is taken to detect paroxysmal brain activity. On the EEG, various changes in the bioelectrical activity of the brain can be detected, depending on the nature of the seizures and changes in the nervous system in which they arose. So, with infantile spasms on the EEG, changes are noted that are characteristic only for this type of seizure - hypsarrhythmia. Such studies as craniography, diaphanoscopy, computed tomography, REG, angiography, also in some cases allow us to clarify the cause of the convulsive syndrome.

If convulsions first occur in infancy, then along with the above studies, an EEG is taken to detect paroxysmal brain activity. On the EEG, various changes in the bioelectrical activity of the brain can be detected, depending on the nature of the seizures and changes in the nervous system in which they arose. So, with infantile spasms on the EEG, changes are noted that are characteristic only for this type of seizure - hypsarrhythmia. Such studies as craniography, diaphanoscopy, computed tomography, REG, angiography, also in some cases allow us to clarify the cause of the convulsive syndrome.

The impact of seizures on developmental delay depends on the age of the child, the level of psychomotor development before the onset of seizures, the presence of other neurological disorders, the nature of seizures, their frequency and duration. The younger the child's age at the onset of seizures, the more pronounced will be the delay in psychomotor development. If convulsions occurred in a healthy child, were episodic and short-term, then they themselves may not have a significant impact on age-related development and may not cause neurological disorders. These are, as a rule, single febrile and affective-respiratory convulsions. In all other cases, paroxysms, especially if they were long and repeated, in turn can cause irreversible changes in the central nervous system. Seizures that appeared against the background of psychomotor developmental delay and (or) other neurological disorders complicate the course of the underlying disease, exacerbating developmental delay. The child loses acquired motor, mental and speech skills.

These are, as a rule, single febrile and affective-respiratory convulsions. In all other cases, paroxysms, especially if they were long and repeated, in turn can cause irreversible changes in the central nervous system. Seizures that appeared against the background of psychomotor developmental delay and (or) other neurological disorders complicate the course of the underlying disease, exacerbating developmental delay. The child loses acquired motor, mental and speech skills.

The nature of convulsive paroxysms also affects the delay in age-related development. The most unfavorable in this regard are infantile spasms, which primarily cause a profound mental retardation. According to J. R. Lacy and J.K. Penry (1976), mental retardation is observed in 75-93% of patients with infantile spasms. The formation of motor skills is also disturbed or they are completely lost, depending on the age at which convulsions began. Regardless of whether seizures appear in the midst of apparent well-being or against the background of an already existing developmental delay, their addition and lack of effectiveness from ongoing therapy lead to a loss of points on the age development scale, and the loss is steadily increasing.