Baby feeding styles

What's Your Feeding Style? | Parental Feeding

Learn about your style of feeding your child and whether it’s helping you raise a healthy eater, and what you can do if it’s not.

You have a hairstyle, a fashion style, a style of walking and talking, and more. You also have a parental feeding style — or maybe several feeding styles rolled into one.

In this article, you’ll learn the four common parental feeding styles, their impact on your child’s eating, and how they show up day-to-day.

What is a Parental Feeding Style?Your feeding style summarizes the general attitudes and philosophies you have about feeding your child.

There are four recognized parental feeding styles: Controlling, Indulgent, Uninvolved and Diplomatic.

Each feeding style influences our daily interactions around the meal table and our child’s eating habits and relationship with food.

As a pediatric nutritionist, I think understanding this concept is essential.

Feeding your child is arguably one of the most time-consuming and grueling jobs of parenthood. It’s often thankless and sometimes plagued with parental insecurity and low confidence.

Many parents struggle and muddle through feeding their children.

Not to mention the daily effort can overwhelm. Think about all the planning, buying, preparing, serving, and cleaning up that goes along with feeding a family.

It’s a lot!

Here is a sobering statistic: throughout an 18 year childhood, you will probably feed your child over 28,000 times (assuming you provide the recommended age-appropriate meals and snacks).

You really need to know how to raise a healthy eater, and in particular, how parental feeding styles play into the big picture.

How Does Your Feeding Style Relate to Parenting?Researchers in feeding kids suggest that feeding styles, or the attitude you use in feeding your child, will closely mirror your parenting style.

When you see other parents’ parenting, you probably recognize that everyone has their own style. It may also attract you to those parents who parent like you.

How you parent and how you feed are similar.

Although you use one feeding style most of the time, it can mingle and overlap with one or more feeding styles.

You’re a Product of Your Own Childhood FeedingOur style mimics our experiences as a child. For example, if you had to finish your meal before you could leave the table, then you may require your own child to do the same.

Your style is deeply ingrained from childhood, and may become your “go to” method for feeding. Or, if it was a negative childhood experience, you may want to avoid repeating the past.

Discover the Four Parental Feeding StylesNot only are food and nutrition important considerations in the health of your child, the magnitude of daily feeding interactions is equally, if not more, important.

As I mentioned, you likely have one style prevalent in your day to day feeding interactions with your child. However, you can dip into every one of these styles from time to time.

For example, when you’re stressed and busy, you might be uninvolved in feeding your child. When you’re in party mode, you may be indulgent. When your child is picky and underweight, you might become more controlling with feeding.

Let’s look at the four different feeding styles and see where you end up!

Which Feeding Style Represents You?The scientific literature recognizes four different approaches. Over time, some of these descriptive names have changed, and more recently they are being redefined under the term “food parenting.”

I have taught a course for nutrition professionals to help them understand this new material.

Keep reading to the bottom, as I’ve saved the most desirable feeding style for last. It’s the one you’ll want to work toward.

The Controlling Feeding StyleWe also know this as a “parent-centered” feeding approach. In the realm of feeding, we associate this style with “The Clean Your Plate Club,” where rules about eating reign, from trying new foods to completing a meal.

In the realm of feeding, we associate this style with “The Clean Your Plate Club,” where rules about eating reign, from trying new foods to completing a meal.

Here are some common “rules” you might see:

Dessert is contingent upon eating dinner.

Parents plate the food for their children.

Eating is directed by the parent, such as “take another bite” or “finish your food,” rather than self-directed by the child and his natural appetite.

The child may not have much say in food choice, and his food preferences and appetite may be ignored by the parent’s wishes around diet quality and eating.

Because of this approach, children may lose a sense of their appetite and an ability to regulate it well. They may overeat to comply with parental requests to eat more or finish the plate of food. Or, they may eat less than they need because they’re pushed or pressured too much.

Weight problems, both underweight and overweight, are associated with this feeding style.

Being indulgent is also known as the lax or loose style of parenting around food. I often refer to the permissive parent as “The ‘Yes’ Parent.”

A parent with this style shows the following characteristics:

Even though “no” or limitations may be the first response to extra food requests or treats, “yes” ultimately reigns.

The rules and limits around food and eating are lax, or loose.

The parent is hyper-sensitive to food preferences and requests.

The classic example of this is the mother who is attempting to manage the vocal child in the grocery store who wants candy at the checkout stand. He begs and begs, hearing, “no, no, no…” until Mom wears down and says, “Well….okay, I guess so.”

Children raised with an indulgent style of feeding have a tough time self-regulating their food intake, particularly around sweets.

I frequently see a lack of structured meals and snacks, and a lack of food boundaries.

As a result, children may struggle with their weight, as research shows there may be few limits on high-calorie foods.

[Watch What’s Your Parent Feeding Style on YouTube!]

The Uninvolved Feeding StyleThis style is less studied in the literature, but as a practitioner, I have seen it in action.

The parent is often:

Ill-prepared in the food department, not shopping for food regularly. Cabinets and refrigerators may be empty or lacking in a variety of food.

There may be no plan for meals, or meals may be left to the last minute.

Food and eating may lack importance to the parent, and that may transfer to feeding their child.

Children who experience an uninvolved feeding style may feel insecure or nervous about food, being unsure about when they will have their next meal, if they will like it, or whether it will be enough.

These children may become overly focused on food and frequently question the timing and details around mealtime.

The three feeding styles – controlling, indulgent and uninvolved — are considered to be negative feeding styles. In short, they interfere with your child’s developing relationship with food. In other words, how he sees food, how he interacts with it, and how he views himself in relationship with food.

A poor relationship with food can lead to poor food choices, under- or overeating, and/or poor self-image and self-esteem.

It’s so important to move toward a positive feeding style! And this is where the diplomatic feeding style enters the picture.

The Diplomatic Feeding StyleI call this the “Love with Limits” feeding style, because it promotes independent thinking and eating regulation within your child, but it also sets boundaries your child is expected to operate in.

The diplomatic feeding style focuses on the details around the meal (what will be served, when it will happen, and where it will be served), but allows the child to decide if they will eat what is prepared, and how much they will eat.

This diplomacy in feeding is based in The Division of Responsibility, coined by Ellyn Satter, and the research in this feeding practice.

Trusting your child — his ability to recognize hunger and fullness signals and then eat the amount of food to satisfy those cues — forms the basis of the diplomatic feeding style.

Food boundaries or limits also compose the foundation of this feeding style.

Children raised using this feeding style are leaner, good at regulating their food consumption, and secure with food and eating, according to the research.

In fact, the most current research advocates this style of parental feeding style as an effective childhood obesity prevention approach.

I notice that parents who approach feeding kids in this manner have fewer struggles with healthy eating in their kids!

What about Feeding Styles for Babies?Good question! In young infants and toddlers, responsive feeding is the focus. This lays the foundation for later childhood (hello, toddlerhood!) when feeding styles and the associated feeding practices can get troublesome.

This lays the foundation for later childhood (hello, toddlerhood!) when feeding styles and the associated feeding practices can get troublesome.

Tune into my podcast where I interview experts in child nutrition and feeding, as well as share my own views on what it means to be a great feeder.

My program, The Nourished Child Blueprint, does a deep dive into feeding styles, the daily practices we use when feeding kids, and how these play out in their autonomy with food and relationship with it.

Take a look at my parent nutrition education website, The Nourished Child, where you’ll find several workshops, classes and guidebooks to help you raise a healthy child, inside and out.

Last, be sure to join my newsletter, The Munch, where I answer parent questions, review the latest science in child nutrition and feeding, and help you learn more!

I updated this post in March 2022.

Baby-Led Weaning is a New Way of Feeding Your Baby - Learn More About it

Every parent remembers when they first introduced their baby to solid foods. This momentous occasion of spoon-feeding them pureed food is considered a major milestone for babies and their parents.

This momentous occasion of spoon-feeding them pureed food is considered a major milestone for babies and their parents.

Today however, more and more parents are opting to skip the applesauce and mashed sweet potatoes and instead are adopting a new feeding technique called “baby-led weaning” ( or BLW) for their babies. This alternative approach to feeding, first introduced in the UK a decade ago, involves introducing solid chunks of foods much earlier on by placing them on the baby’s high chair and letting them grasp the food and feed themselves directly. As the name implies, feeding time is led by the baby as they determine the pace and the amount of food they consume; basically, baby-led weaning puts the baby in charge.

While children all develop at different paces, advocates of baby-led weaning agree that this method of eating shouldn’t be introduced until the baby is ready. Cues to begin BLW include making sure that your baby can sit up straight unassisted, have good neck strength and be able move food to the back of their mouth with up and down jaw movements. Most babies develop these skills by the sixth month, but some babies may not fully develop them until they are nine months old.

Most babies develop these skills by the sixth month, but some babies may not fully develop them until they are nine months old.

Proponents of BLW believe that it holds many benefits, including enhancing baby’s hand-eye coordination and other fine motor skills, including using their thumb and index finger to grasp their food. They also feel that it will produce healthier eaters than spoon-fed babies because BLW eaters get to choose how much they eat as opposed to traditional feeding methods, which sometimes results in force feeding. Other advantages that BLW supporters claim to be true is that it creates a more enjoyable feeding experience for babies and less stress on their parents.

Detractors of baby-led weaning feeders point out that these babies are generally underweight as compared to spoon-fed babies because they simply do not ingest that much when they are first introduced to this way of eating due to difficulties grabbing food. BLW babies also tend to be iron-deficient because they aren’t consuming the iron-fortified cereals that spoon–fed babies typically eat. Lastly, a big concern for many parents is the increased choking hazards associated with BLW, and while the American Academy of Pediatrics doesn’t have opinion of BLW, they do state that babies are ready for solid food once they are ready to sit up on their own and bring their hand to their mouth.

Lastly, a big concern for many parents is the increased choking hazards associated with BLW, and while the American Academy of Pediatrics doesn’t have opinion of BLW, they do state that babies are ready for solid food once they are ready to sit up on their own and bring their hand to their mouth.

If you are considering baby led weaning for your child, here are a few tips:

- Continue breast feeding and / or formula feeding as this will continue to be your baby’s biggest source of nutrition until they are 12 months old.

- Begin BLW feedings with softer foods, such as ripe fruits, cooked egg yolks, and shredded meats, poultry and fish.

- Avoid foods that can pose as choking hazards, such as nuts, grapes, popcorn, or foods cut into coin shapes, like hot dogs.

- Do not leave your child unattended during BLW feeding times. Continue to supervise and socialize with them while they eat and to have them eat when the rest of the family does.

- Don’t panic if your baby gags as it is a safe a natural reflex.

Instead of overreacting, prepare for a choking event by familiarizing yourself with the infant-specific Heimlich maneuver.

Instead of overreacting, prepare for a choking event by familiarizing yourself with the infant-specific Heimlich maneuver. - Introduce new foods one at a time to pinpoint potential food allergies. A recommended length of time is three to four days between foods.

- The goal of BLW is to let your baby explore eating at their own pace. This may include the smashing, smearing, or dropping of food, so prepare for a mess.

Before you decide to adopt BLW to your child, it is a good idea to discuss with your child’s pediatrician as it may not be a good idea for all babies, especially those babies with known developmental delays or neurological issues.

To make an appointment with a pediatrician at Flushing Hospital’s Ambulatory Care Center, please call 718-670-5486.

All content of this newsletter is intended for general information purposes only and is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Please consult a medical professional before adopting any of the suggestions on this page. You must never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking medical treatment based upon any content of this newsletter. PROMPTLY CONSULT YOUR PHYSICIAN OR CALL 911 IF YOU BELIEVE YOU HAVE A MEDICAL EMERGENCY.

You must never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking medical treatment based upon any content of this newsletter. PROMPTLY CONSULT YOUR PHYSICIAN OR CALL 911 IF YOU BELIEVE YOU HAVE A MEDICAL EMERGENCY.

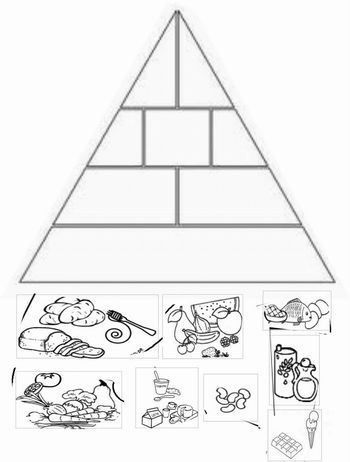

Helping children develop healthy eating habits

Maureen M. Black, PhD, Kristen M. Hurley, PhD

University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA

, 2nd rev. ed. (English language). Translation: August 2015

Introduction

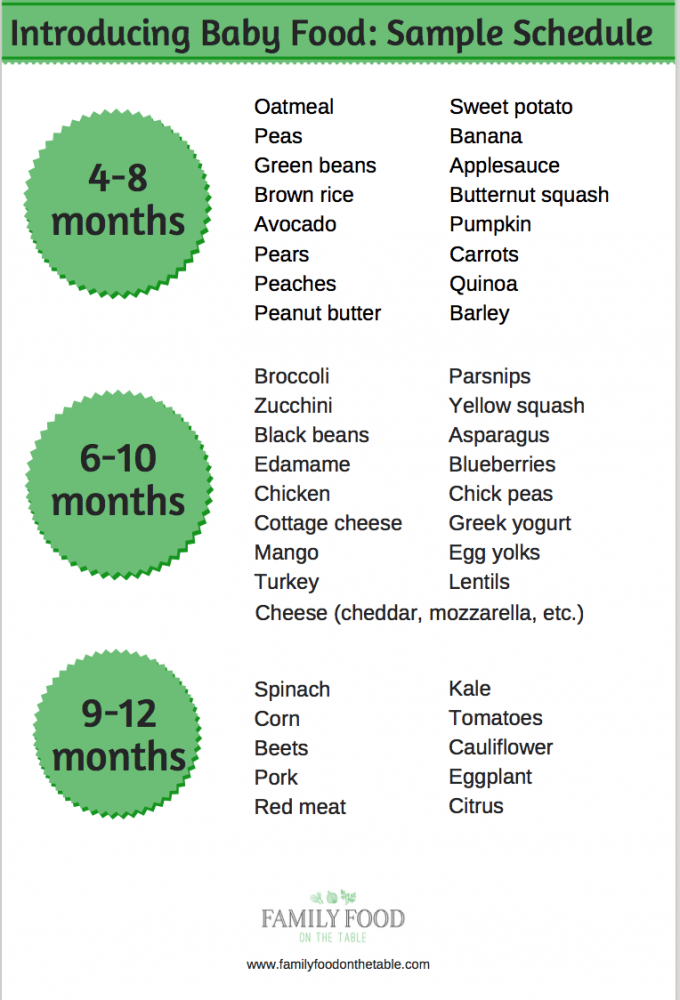

The first year of a child's life is characterized by rapid age-related changes related to nutrition. As infants gain control of their own bodies, they move from the stage of sucking liquids in a recumbent or reclining position to the stage of eating solid foods in a sitting position. Oral motor skills are developed, moving from a basic "sucking-swallowing" mechanism based on breast milk or formula to a "chewing-swallowing" mechanism based on the consumption of semi-solid foods, gradually moving to more complex combined types of food. 1.2 When infants are already well regulated in their movements, they move from passive feeding, in which someone feeds them, to self-feeding, at least occasionally. The infant's diet is enriched: through the introduction of mashed potatoes and specially prepared foods, the transition is made from breast milk and formula for feeding to the family diet. By the end of the first year of life, children are already able to sit, chew and swallow on their own, consuming different types of food, learn to eat independently and move on to a diet and diet that is characteristic of the whole family.

Oral motor skills are developed, moving from a basic "sucking-swallowing" mechanism based on breast milk or formula to a "chewing-swallowing" mechanism based on the consumption of semi-solid foods, gradually moving to more complex combined types of food. 1.2 When infants are already well regulated in their movements, they move from passive feeding, in which someone feeds them, to self-feeding, at least occasionally. The infant's diet is enriched: through the introduction of mashed potatoes and specially prepared foods, the transition is made from breast milk and formula for feeding to the family diet. By the end of the first year of life, children are already able to sit, chew and swallow on their own, consuming different types of food, learn to eat independently and move on to a diet and diet that is characteristic of the whole family.

As children make the transition to a family diet, the advice is not only about food, but also about nutrition. A variety of healthy foods improves the quality of the diet in the same way as early and regular recognition of new types of food by the child. Data on infants and young children aged 6 to 23 months, collected in 11 countries around the world, show a positive relationship between dietary diversity and nutritional status (nutritive status). 3 Teaching a child to consume fruits and vegetables during infancy and early childhood is associated with the adoption of these types of food at an older age. 4-6

Data on infants and young children aged 6 to 23 months, collected in 11 countries around the world, show a positive relationship between dietary diversity and nutritional status (nutritive status). 3 Teaching a child to consume fruits and vegetables during infancy and early childhood is associated with the adoption of these types of food at an older age. 4-6

Eating habits and preferences are formed in children at an early age. If children forgo nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables, mealtimes can become stressful or wrestling. As a result, children may be deprived of both the nutrients they need and healthy, understanding relationships between them and caregivers. Adults who are inexperienced or stressed, and those who themselves have unhealthy eating habits, need help to establish healthy and fulfilling eating behaviors in children during the meal.

Subject

Eating problems occur in 25% - 45% of all children, especially during the period when children learn new skills, and new types of food or expectations associated with eating them become real for them test. 7 For example, the period of infancy and early childhood is characterized by a desire for independence - children try to do everything on their own. When these characteristics are also applied to eating behavior, it suggests that children may be neophobic (fear of trying new foods) and insist on a limited set of foods consumed, 8 which further leads to the perception of these children as fastidious eaters.

7 For example, the period of infancy and early childhood is characterized by a desire for independence - children try to do everything on their own. When these characteristics are also applied to eating behavior, it suggests that children may be neophobic (fear of trying new foods) and insist on a limited set of foods consumed, 8 which further leads to the perception of these children as fastidious eaters.

Most eating problems are temporary and easily resolved with little or no intervention. However, when such problems continue for a long time, their presence can slow down the child's growth, development and worsen relationships with people caring for him. This leads to long-term problems with the health and development of the child. 9 Children with chronic eating problems may be at risk for growth and behavioral problems if caregivers do not seek help in a timely manner, allowing a critical situation to develop.

Issues

Eating habits are influenced by age, family or environment.![]() As they mature and are able to make the transition to a family diet, their internal regulatory signals for hunger and satiety may be suppressed by family and cultural patterns. In families where adults lead by example in healthy eating, children are more likely to eat more fruits and vegetables than children in families where they do not. At the same time, in a family where it is customary to eat less healthy food, snacks are abused, children are likely to have eating habits and taste preferences characterized by the consumption of excess amounts of fat and sugar. 10 In terms of environmental influences, children's exposure to fast food restaurants and similar establishments resulted in increased consumption of high-fat foods, such as french fries, while not eating more nutrient-dense foods, such as fruits and vegetables. 11 What's more, adults may not realize that many commercial products advertised as products for children (such as sugary drinks) can satisfy hunger or thirst but provide minimal nutritional intake.

As they mature and are able to make the transition to a family diet, their internal regulatory signals for hunger and satiety may be suppressed by family and cultural patterns. In families where adults lead by example in healthy eating, children are more likely to eat more fruits and vegetables than children in families where they do not. At the same time, in a family where it is customary to eat less healthy food, snacks are abused, children are likely to have eating habits and taste preferences characterized by the consumption of excess amounts of fat and sugar. 10 In terms of environmental influences, children's exposure to fast food restaurants and similar establishments resulted in increased consumption of high-fat foods, such as french fries, while not eating more nutrient-dense foods, such as fruits and vegetables. 11 What's more, adults may not realize that many commercial products advertised as products for children (such as sugary drinks) can satisfy hunger or thirst but provide minimal nutritional intake.![]() 12

12

A number of nationwide studies have documented excessive consumption of high-calorie foods during early childhood, 13.14 while many children consume critically low amounts of fruits, vegetables and essential micronutrients. 15 By the time they enter primary school, many children get half their fluid intake from sugary drinks. 16 This eating habit is undoubtedly developed during early childhood and preschool age. The presence of these unhealthy eating habits (eating foods high in fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates; sugary drinks; eating limited fruits and vegetables) increases the likelihood of micronutrient deficiencies (such as iron deficiency anemia) and overweight in young children. 17

Scientific context

The process of eating is often studied through observations or adult reports of eating behavior. Some investigators rely on clinical study of groups of children with stunting or nutritional problems, others select children without any abnormalities for research.

Key Questions

Key Questions are about the development of eating habits from infancy through early childhood, and the methods by which children report feeling hungry or full. In addition, this includes studying the reasons why some children (so-called "picky eaters") have selective food preferences. Key challenges for caregivers and families are to find ways to promote healthy eating habits in young children, encourage children to eat healthy foods, and prevent problems with feeding and growth.

Recent Research Findings

Attachment and Nutrition

Healthy eating habits develop in infancy as infants and their parents develop a partnership in which they recognize and interpret both verbal and non-verbal communication cues each other. This reciprocal process forms the basis for building an emotional bond or attachment in infants and caregivers that is an integral part of healthy social functioning. 18 If communication between the child and adults is disrupted, characterized by incoherent, unresponsive interactions, bonds of attachment may be unreliable, resulting in eating can turn into unproductive, exhausting quarrels over food.

Infants who do not communicate clearly about their needs, or who do not respond to caregivers' attempts to teach them regular and predictable habits related to eating, sleeping, and playing, are at risk of acquiring regulatory problems associated with eating as well. 9 Premature or sick babies may react more slowly than full-term babies, making it more difficult for these babies to express feelings of hunger or fullness. Adults who do not recognize signs of satiety in their children tend to overfeed them, causing infants to associate satiety with frustration and conflict.

Feeding in the context of the adult-child relationship

Variability in the context of the adult-child relationship during feeding is associated with feeding behavior and growth of the child. 19 Aspects of parental behavior and guardianship, which include factors of perception and understanding of the child's behavior, apply to the nature of feeding (Table 1). 20,21,22 Responsive feeding reflects an interaction-based pattern of behavior in which adults provide control and developmentally appropriate responses to a child's signals of hunger or satiety. The unresponsive feeding process is marked by a lack of reciprocity between adults and the child. This is characterized by parents being overly in control of the feeding process (by forcing the child to eat or limiting the child's diet), or by the fact that the child controls the feeding process (for example, requires a limited menu, or eats only after much persuasion), or by the fact that an adult ignores the child's signals, or cannot organize the correct diet (isolated feeding). 23.24

20,21,22 Responsive feeding reflects an interaction-based pattern of behavior in which adults provide control and developmentally appropriate responses to a child's signals of hunger or satiety. The unresponsive feeding process is marked by a lack of reciprocity between adults and the child. This is characterized by parents being overly in control of the feeding process (by forcing the child to eat or limiting the child's diet), or by the fact that the child controls the feeding process (for example, requires a limited menu, or eats only after much persuasion), or by the fact that an adult ignores the child's signals, or cannot organize the correct diet (isolated feeding). 23.24

Table 1. The context of the adult-child relationship in the process of feeding: patterns of parenting and feeding the child

parents and child are in a relationship where requirements are clearly expressed and there is a mutual interpretation of signals for feeding. Responsive feeding is characterized by short-term interaction based on behavioral characteristics and consistent with a certain stage of development of the child. In the course of this interaction, both sides easily compromise. 22,25,26

Responsive feeding is characterized by short-term interaction based on behavioral characteristics and consistent with a certain stage of development of the child. In the course of this interaction, both sides easily compromise. 22,25,26

A controlling feeding style, well structured but low in caring, is characteristic of parents who use forceful or restrictive strategies to control the feeding process. A controlling feeding style is part of an authoritarian parenting model and may include overly assertive behaviors such as loud talking, force feeding, or other ways to get a child to do what they want. 27 Parents who control the feeding process can suppress the child's internal regulatory signals of hunger or satiety. 28 Infants' innate ability to self-regulate energy consumption disappears during early childhood due to the influence of family and cultural patterns. 29

An indulgent feeding style, characterized by a high level of caring and less structure, is an element of the indulgent parenting model. With this style of feeding, parents allow the child to decide for himself what to eat and when. 23 If the parents do not refer the child, the child is more likely to choose foods high in salt and sugar over a more balanced diet that includes vegetables. 23 Thus, an indulgent feeding style can be problematic given the genetic predisposition of infants to salty or sweet foods. 30 Babies whose parents practice indulgent feeding styles often weigh more than children of parents who use other feeding styles. 24

With this style of feeding, parents allow the child to decide for himself what to eat and when. 23 If the parents do not refer the child, the child is more likely to choose foods high in salt and sugar over a more balanced diet that includes vegetables. 23 Thus, an indulgent feeding style can be problematic given the genetic predisposition of infants to salty or sweet foods. 30 Babies whose parents practice indulgent feeding styles often weigh more than children of parents who use other feeding styles. 24

Detached feeding style, characterized by both low levels of nurturance and a less structured structure, is characteristic of parents with a lack of knowledge and involvement in their child's eating behavior. 23 A detached feeding style may have features such as lack of active assistance or verbalization during feeding, lack of rapport between parent and child, negative feeding environment, and lack of an orderly structure or defined feeding pattern. Indifferent parents often ignore both the feeding advice and the child's signals of hunger or satiety; they may not know what and when their child eats. Egeland and Sroufe 31 found that children of distant or psychologically unavailable parents were more likely to experience anxiety than children whose parents were actively involved. Accordingly, a detached feeding style is an element of a detached parenting style. 23

Indifferent parents often ignore both the feeding advice and the child's signals of hunger or satiety; they may not know what and when their child eats. Egeland and Sroufe 31 found that children of distant or psychologically unavailable parents were more likely to experience anxiety than children whose parents were actively involved. Accordingly, a detached feeding style is an element of a detached parenting style. 23

Several recent systematic reviews have shown an association between parental control of feeding and infant and young child weight gain and/or weight class. 24,32,33 Control feeding is associated with weight gain (eg, children whose parents have a restrictive feeding style tend to overeat) 34 and weight loss (eg, children who are forced to eat more do not tend to overeat). 35 However, the cross-sectional nature of most studies, coupled with a tendency to rely solely on parental behavioral data without considering the importance of interactions during feeding, makes it difficult to understand parent-child interactions during feeding. A recent double-blind study of infants in Australia found that adherence to preventive infant feeding guidelines led to normal weight gain and improved mutual understanding during feeding, as judged by the respondents. 36 More research is needed to better understand strategies for promoting healthy relationships that are important for a child's feeding and healthy growth.

A recent double-blind study of infants in Australia found that adherence to preventive infant feeding guidelines led to normal weight gain and improved mutual understanding during feeding, as judged by the respondents. 36 More research is needed to better understand strategies for promoting healthy relationships that are important for a child's feeding and healthy growth.

Food preferences

Children who grow up in families where parents set an example of healthy eating behavior (for example, eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables) develop similar food preferences. 4

Food preferences are also influenced by accompanying conditions. Children are more likely to avoid foods associated with unpleasant physical symptoms, such as nausea or pain. They may also avoid eating food associated with anxiety or distress caused by feeding disputes and confrontations.

Children also choose food based on qualities such as taste, texture, smell, temperature, or appearance, as well as environmental factors such as setting, presence of others, and perceived consequences of eating or not eating. For example, consequences of eating may include satiety, participation in a social function, or parental attention. Consequences of not eating can include things like extra play time, being the center of attention, or snacking instead of a normal meal.

For example, consequences of eating may include satiety, participation in a social function, or parental attention. Consequences of not eating can include things like extra play time, being the center of attention, or snacking instead of a normal meal.

The degree of familiarity with the taste of food increases the likelihood that the child will accept it. 37.38 Parents can make it easier to introduce new foods to their diet by regularly pairing them with familiar foods until the food becomes habitual.

Conclusions

Eating habits are formed early in development as a response to internal regulatory cues, parent-child relationships, dietary patterns, food offerings, and family behavior patterns. Teaching children to eat fruits and vegetables early in their development develops a lifelong preference for these foods. It is necessary to conduct research on the factors that determine the context of the relationship between an adult and a child in a feeding situation, at an individual level, in an interaction situation and at the level of the external environment. The relationship between responsive/non-responsive feeding styles and children's feeding behavior in relation to weight gain should also be explored, and population-specific tools to measure responsive/non-responsive feeding characteristics should be developed. 24

The relationship between responsive/non-responsive feeding styles and children's feeding behavior in relation to weight gain should also be explored, and population-specific tools to measure responsive/non-responsive feeding characteristics should be developed. 24

Eating behavior during early childhood largely depends on parents and is developed through the acquisition of experience with food and its use. A system of education and support involving health professionals (i.e. health visitors, family doctors and pediatricians) and nutrition programs should be established so that parents always have the opportunity to seek help with their child's eating behavior.

Parents should combine their own meals with the feeding of the child in order to instill similar eating habits in him, and also to make the process of eating a pleasant experience for the child. Eating together allows children to watch their parents try new foods and helps them express feelings of hunger and satiety, as well as enjoyment of certain foods. 39

39

Parents control both the choice of food and the creation of a certain atmosphere in the process of feeding. Their "job" is to provide children with healthy food at fixed times and in pleasant surroundings. 39 By developing a certain diet, parents help children learn to consciously wait for the next meal. Children acquire the knowledge that the feeling of hunger will soon pass, and that they have no reason to be anxious or irritated. Children should not snack or eat throughout the day - this develops a sense of anticipation of a meal and the appearance of an appetite at a certain time. 39

Meals should be a pleasant family event, when all family members eat together and discuss the events of the day. When the duration of meals is shortened (less than 10 minutes), children may not have enough time to eat, especially during the period when they are learning to eat on their own, and the process of eating slows down. At the same time, it is difficult for a child to eat food that lasts more than 20 or 30 minutes, so such food can cause a feeling of disgust.

When feeding is accompanied by distractions such as watching TV, family disputes, or other extraneous activities, it can be difficult for children to focus on food. Parents should separate meal times from play activities and avoid using toys, playing games, and not watching TV - all of these factors can distract the child from eating. Special equipment for children – high chairs, bibs and small utensils – encourages feeding and enables children to develop self-feeding skills.

Advice

Advice may be environmental, family or personal. In the environment, having healthy and tasty menus for young children at fast food restaurants can help avoid many of the problems associated with regularly eating high-fat foods (like french fries) instead of more nutritious foods like fruits and vegetables. Infant feeding recommendations should include the following information: information about the child's nutritional needs, methods to encourage healthy eating behaviors (including learning to recognize hunger or satiety signals and developing a specific type of interaction between parents and child during feeding), information on choosing the right time for about feeding, about ensuring regular feeding hours, about introducing new food into the diet through its modeling, data on ways to neutralize stressful and conflict situations during feeding. In terms of individual counseling, programs that help children develop healthy eating habits through nutrient-rich foods and develop the habit of eating to satisfy hunger rather than emotional needs can help prevent potential health and developmental problems. 40

In terms of individual counseling, programs that help children develop healthy eating habits through nutrient-rich foods and develop the habit of eating to satisfy hunger rather than emotional needs can help prevent potential health and developmental problems. 40

Literature

- Bosma J. Development and impairments of feeding in infancy and childhood. In: Groher M.E., ed. Dysphagia: Diagnosis and management . 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997:131-138.

- Morris SE. Development of oral motor skills in the neurologically impaired child receiving non-oral feedings Dysphagia 1989;3:135-154.

- Arimond M, Ruel MT. Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: Evidence from 11 demographic and health surveys. The Journal of Nutrition 2004;134:2579-2585.

- Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, Ziegler P, Reidy K. Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predictary dietary variety in school-aged children? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2002;34(6):310-315.

- Schwartz C, Scholtens PA, Lalanne A, Weenen H, Nicklaus S. Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite . 2011;57(3):796-807.

- Mennella JA, Nicklaus S, Jagolino AL, Yourshaw LM. Variety is the spice of life: strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable acceptance during infancy. Physiol Behav . 2008;22;94(1):29-38.

- Linscheid TR, Budd KS, Rasnake LK. Pediatric feeding disorders. In: Roberts MC, ed. Handbook of pediatric psychology . New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003:481-498.

- Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L. What kind of exposure reduces children's food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. Appetite 1987;9(3):171-178.

- Keren M, Feldman R, Tyano S. Diagnoses and interactive patterns of infants referred to a community-based infant mental health clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2001;40(1):27-35.

- Palfreyman Z, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Development of the Parental Modeling of Eating Behaviours Scale (PARM): links with food intake among children and their mothers. Maternal and Child Nutrition . 2012 [Epub ahead of print].

- Zoumas-Morse C, Rock CL, Sobo EJ, Neuhouser ML. Children's patterns of macronutrient and intake associations with restaurant and home eating. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2001;101(8):923-925.

- Smith MM, Lifshitz F. Excess fruit juice consumption as a contributing factor in nonorganic failure to thrive. Pediatrics 1994;93(3):438-443.

- Ponza M, Devaney B, Ziegler P, Reidy K, Squatrito C. Nutrient intakes and food choices of infants and toddlers participating in WIC. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):71-79.

- Devaney B, Kalb L, Briefel R, Zavitsky-Novak T, Clusen N, Ziegler P. Feeding infants and toddlers study: overview of the study design.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):8-13.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):8-13. - Picciano MF, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL, Mitchell DC, Murray-Kolb L, McConahy KL. Nutritional guidance is needed during the dietary transition in early childhood. Pediatrics 2000;106(1):109-114.

- Cullen KW, Ash DM, Warneke C, de Moor C. Intake of soft drinks, fruit-flavored beverages, and fruits and vegetables by children in grades 4 through 6. American Journal of Public Health 2002;92(9): 1475-1477.

- Brotanek JM, Gosz J, Weitzman M, Flores G. Secular trends in the prevalence of iron deficiency among US toddlers, 1976-2002. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2008;162:374-81.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . New York: Psychology Press, 1978.

- Rhee K. Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning.

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2008;615:11–37.

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 2008;615:11–37. - Baumrind D. Rearing competent children In: Damon W, ed. Child development today and tomorrow. San-Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1989:349-378.

- Maccoby EE, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, ed. Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development. Vol 4 . New York, NY: John Wiley; 1983:1-101.

- Black MM & Aboud FE. Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. Journal of Nutrition 2011;141(3):490-4.

- Hughes SO, Power TG, Fisher JO, Mueller S, Nicklas TA. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 2005;44(1):83-92.

- Hurley KM, Cross MB, Hughes SO. A systematic review of responsive feeding and child obesity in high-income countries.

Journal of Nutrition 2011;141:495-501.

Journal of Nutrition 2011;141:495-501. - Leyendecker B, Lamb ME, Scholmerich A, Fricke DM. Context as moderators of observed interactions: A study of Costa Rican mothers and infants from differing socioeconomic backgrounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development 1997;21(1):15-24.

- Kivijarvi M, Voeten MJM, Niemela P, Raiha H, Lertola K, Piha J. Maternal sensitivity behavior and infant behavior in early interaction. Infant Mental Health Journal 2001;22(6):627-640.

- Beebe B, Lachman F. Infant research and adult treatment: Co-constructing interactions . Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press; 2002.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO. Mothers' child-feeding practices influence daughters' eating and weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000;71(5):1054-1061

- Birch LL, Johnson SL, Andresen G, Peters JC, Schulte MC. The variability of young children's energy intake. New England Journal of Medicine 1991;324(4):232-235.

- Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition 1999;19:41-62.

- Egeland B, Sroufe LA. attachment and early maltreatment. Child Development 1981;52(1):44-52.

- DiSantis KI, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Fisher JO. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: a systematic review. International Journal of Obesity 2011;35:480-92.

- Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obesity Research 2004;12(11):1711-1722.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003;78(2):215-220.

- Fisher JO, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. Parental influences on young girls' fruit and vegetable, micronutrient, and fat intakes.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2002;102(1):58-64.

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2002;102(1):58-64. - Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Battistutta D, Nicholson JM, Perry R, Magarey A. Evaluation of an intervention to promote protective infant feeding practices to prevent childhood obesity: outcomes of the NOURISH RCT at 14 months of age and 6 months post the first of two intervention modules. International Journal of Obesity (Lond) . 2012 Oct;36(10):1292-8.

- Birch LL. Children's preferences for high-fat foods. Nutrition Reviews 1992;50(9):249-255.

- Birch LL, Marlin DW. I don't like it; I never tried it: effects of exposure on two-year old children's food preferences. Appetite 1982;3(4):353-360.

- Satter E. Child of mine: Feeding with love and good sense . Palo Alto, CA: Bull Publishing; 2000.

- Black MM, Cureton LA, Berenson-Howard J. Behavior problems in feeding: Individual, family, and cultural influences. In: Kessler DB, Dawson P, eds.

Failure to thrive and pediatric undernutrition: A transdisciplinary approach . Baltimore, Md.: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 1999:151-169.

Failure to thrive and pediatric undernutrition: A transdisciplinary approach . Baltimore, Md.: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 1999:151-169.

Breastfeeding in public | Tips for Breastfeeding Moms

Open breastfeeding in public takes some getting used to. Here are some tips to help you and your baby feel more confident

Share this information

The beauty of breastfeeding is that everything you need is always at your fingertips: you can feed your baby wherever you are, and the milk temperature will always be just right. But while there's nothing more natural than breastfeeding, the very idea of breastfeeding in front of everyone, especially the first time, can be a little unsettling. Whether you are worried about what others will think or not, our tips will help you prepare for this event.

1: Rehearse

If you feel embarrassed at the prospect of breastfeeding your baby for the first time in a public place, practice in front of a mirror at home to imagine how you will look from the outside. You will surely notice that the chest is not so open at the same time: it is blocked by the head of the child.

You will surely notice that the chest is not so open at the same time: it is blocked by the head of the child.

For starters, try breastfeeding in public in a friendly environment. In the company of other mothers or in a cafe with a friend, you will obviously be more comfortable than alone in the train or in a noisy shopping center.

2: Dress comfortably

When it comes to comfortable clothing for breastfeeding in general and in public places in particular, there are many options. If breastfeeding is going well and you intend to continue, it's worth picking up a few pieces of nursing clothing that will make feeding easier.

“I had a very comfortable nursing shirt. It was possible to discreetly feed the child in it even in winter, since nothing had to be removed. Just put the baby on the slit in the T-shirt and you're done. You can feed anywhere and anytime!” says Caroline, mother of two from France.

However, it is not necessary to buy special nursing clothes - you can just wear two regular T-shirts. “I solved the problem with a stretch blouse that I wore under a loose top. When it was necessary to feed the child, I pulled the jacket under my chest and lifted the top. He covered my chest, and the jacket - my stomach. So it was possible to feed discreetly anywhere, while not freezing and not showing anyone your tummy that sagged after childbirth,” recalls Suzanne, a mother of two children from the UK.

“I solved the problem with a stretch blouse that I wore under a loose top. When it was necessary to feed the child, I pulled the jacket under my chest and lifted the top. He covered my chest, and the jacket - my stomach. So it was possible to feed discreetly anywhere, while not freezing and not showing anyone your tummy that sagged after childbirth,” recalls Suzanne, a mother of two children from the UK.

Other convenient options are tops and dresses with buttons or zips in the front, clothes with straps or side slits. You can also try wraparound styles, collar collars or shawl collars.

“Wrap-around cardigans have been a lifesaver when I have to feed in public,” says Natalie, a UK mom. - I just untied one floor and covered my baby's head with it during feeding or when she cried. And you didn’t have to carry anything with you to disguise.”

3: Know your surroundings

Before you go anywhere with your baby, make a list of good places to feed in advance so you don't have to rush around looking for food at the last minute. Shopping malls, department stores and children's clothing stores often have mother and baby rooms where you can feed your baby in peace and quiet, sitting on a comfortable chair, or use the changing table. Many cafes and hotel restaurants also try to create comfortable conditions for nursing mothers.

Shopping malls, department stores and children's clothing stores often have mother and baby rooms where you can feed your baby in peace and quiet, sitting on a comfortable chair, or use the changing table. Many cafes and hotel restaurants also try to create comfortable conditions for nursing mothers.

“If you're worried, look in advance for places that are friendly to breastfeeding so you know where to go if you need to. Feeding in public can be difficult at first, but over time it gets better and better. And then you do it so quickly and imperceptibly that people around you don’t even realize that you are breastfeeding a baby, ”says Rachel, a mother from the Maldives.

Other potentially suitable locations are fitting rooms in department stores, furniture stores, community centers, libraries, museums, and parks. Ask around moms you know - they can probably share their experience about suitable feeding places nearby.

“In the UAE, children under the age of two are legally allowed to breastfeed. Breastfeeding is highly encouraged here, shopping malls have dedicated facilities for breastfeeding, and mothers who breastfeed in public places like restaurants are treated with respect,” says Fay, mother of two from the UAE.

Breastfeeding is highly encouraged here, shopping malls have dedicated facilities for breastfeeding, and mothers who breastfeed in public places like restaurants are treated with respect,” says Fay, mother of two from the UAE.

4: Try a breastfeeding cape

Some moms prefer to cover themselves and their baby with a cape when breastfeeding in public. The choice here is huge - from simple shawls and ponchos to special capes and aprons with a rigid semicircular hole on top, which allows you to watch the baby during feeding. There is a solution for every taste. And you can also feed your baby in a sling or carrier - this is both convenient and shelters you from prying eyes.

“I recommend buying a carrier,” says Caroline, mother of two in the US. “With a little practice, you can feed on the go, without looking up from other things.”

However, the baby often has the final say. Some babies do not tolerate any capes when feeding, and someone, on the contrary, is distracted if he is not covered. “Both of my babies didn’t like it when I tried to cover them with a shawl during feeding, so I just had to rely on their heads to cover their breasts enough,” recalls Esther, mother of two from the UK.

“Both of my babies didn’t like it when I tried to cover them with a shawl during feeding, so I just had to rely on their heads to cover their breasts enough,” recalls Esther, mother of two from the UK.

5: Know your rights

Breastfeeding in all public places is legal in many countries. Moreover, there are laws aimed at protecting breastfeeding mothers. If you are not sure if there are such laws in your country, search the Internet for information. The best place to start is with the websites of government and health agencies. Or try asking your doctor. You can also ask familiar mothers, friends and relatives about their own experiences. The answers may surprise you.

“In Australia, breastfeeding is widely accepted, and it's quite normal to sit bare-chested in a cafe while a nice waiter takes your order for a low-fat latte!” says Amy, mother of two from Australia.

If someone is upset that you are breastfeeding your baby in a public place, politely remind them of your rights. If you believe that asking you not to breastfeed in a store, cafe, or similar establishment violates your rights, you can file a formal complaint—if you are willing and supported by local law.

If you believe that asking you not to breastfeed in a store, cafe, or similar establishment violates your rights, you can file a formal complaint—if you are willing and supported by local law.

“I once decided to breastfeed my baby at a diner after I had eaten by myself, and I did it right at the table because they didn't have a feeding room. A confused junior manager was sent to me asking if I could move to the women's room for this. I replied that no - do they eat there? Then I was asked to move to a side booth. But I refused here and didn’t budge until we were done!” recalls Maya, a mother of two from Spain.

“My advice is don't worry! I was worried at first, but I regularly had to breastfeed my baby in public places, both in the city and in the countryside. And never once did I encounter a bad attitude, or comments, or sidelong glances. Not everyone, of course, is so lucky, but I breastfed for a whole year, so people had a lot of opportunities to show their bad sides - but nothing like that happened.