Baby food africa

Did Baby Food Jars Horrify African Consumers?

Claim:

African consumers were horrified by an American baby food company's product packaging.

Rating:

Legend

About this rating

One of the perennial favorites in the "bad marketing examples" sweepstakes is the tale of the mythical baby food company that failed to consider cultural differences and thereby ended up repulsing consumers in a foreign market. In this case the horrified victims are Africans, who, used to judging the contents of packaged food products by the pictures on their labels, are aghast to find jars with drawings of babies on them.

Examples:

[Harvard Business Review, 1984]

A large multinational corporation once attempted to sell baby food in an African nation by using packaging designed for its home country market. The company's regular label showed a picture of a baby with a caption describing the kind of baby food contained in the jar. African consumers took one look at the product, however, and were horrified. They interpreted the labels to mean that the jars contained ground-up babies!

[Ricks, 1993]

In areas where many of the people are illiterate, the label usually depicts a picture of what the package contains. This very logical practice proved to be quite perplexing to one big company. It tried to sell baby food in an African nation by using its regular label, which showed a baby and stated the type of baby food in the jar. Unfortunately, the local population took one look at the labels and interpreted them to mean that the jars contained ground-up babies.

Sales, of course, were terrible.5

[Collected on the Internet, 1999]

When Gerber started selling baby food in Africa, they used the same packaging as in the US, with the beautiful Caucasian baby on the label. Later they learned that in Africa, companies routinely put pictures on the label of what's inside, since most people can't read.

Perhaps this tale is so popular because it enables us to feel smugly superior to both the should-have-known-better multinational corporation, and the foreign rubes who don't understand what a jar of baby food is. Note that the examples offered are marvels of non-specificity. No company is mentioned by name in the first two, but by the third a standard law of urban folklore has kicked in and the largest and most well-known purveyor of baby food in America (Gerber) is now identified as the perpetrator. More important, all three examples cite no locale more specific than "Africa," as if the entire continent — from Tunisia to South Africa, from Senegal to Somalia — were home to a homogeneous mass of people, all of whom share a single culture and therefore all think and act alike. No doubt we're supposed to conjure up the old stereotypical images of a mysterious land chock full of dark-skinned, scantily-clad, masked savages with bones through their noses who dance rings around large iron pots of missionary soup in time to the beat of tribal drums. Where else in the world but Africa would one find so many illiterate people? And ho-ho, isn't it funny to think of those cannibalistic primitives as actually being shocked at the thought of someone else's eating ground-up humans? What irony!

No doubt we're supposed to conjure up the old stereotypical images of a mysterious land chock full of dark-skinned, scantily-clad, masked savages with bones through their noses who dance rings around large iron pots of missionary soup in time to the beat of tribal drums. Where else in the world but Africa would one find so many illiterate people? And ho-ho, isn't it funny to think of those cannibalistic primitives as actually being shocked at the thought of someone else's eating ground-up humans? What irony!

This tale is cultural prejudice at its worst; an apocryphal anecdote based on the premise of a whole society of illiterates who don't know what baby food is are credulous enough to believe that someone would sell ground-up babies as food. None of the stores selling this stuff think to correct their misperceptions, of course, nor are we apparently supposed to consider that in regions where "most people can't read," "most people" also don't generally have enough disposable income to be buying individual jars of prepared baby food in the first place.

The coup de grace in debunking improbable tales is to find other (preferably earlier) examples and variants of the same type of story, but with differing details. In this case, we have hit the mother lode. Consider the following tidbit from a 1958 Reader's Digest:

I am in the Mission Supply Store at Madang, New Guinea, and recently the senior pilot with the Christian and Missionary Alliance told me something that gave me pause — and stirred our store into sudden action. The natives around Lake Archbold are unashamedly cannibals and, he reported, they are now convinced that the missionaries are cannibals, too, on evidence observed in missionary homes. They have seen tins with a picture of a fish on the label and, sure enough, the tin contains fish. Likewise a tin of green peas has a label showing peas, and a picture of tomatoes on a tin invariably means tomatoes.

The tinned-goods firm that supplies us has been advised that it must find some means of convincing the natives that its baby food is made for babies and not of babies.

4

Hmm . . . seems this story has not only been around the block before; it's been circling for more than forty years now. This time the setting is New Guinea rather than Africa, the bemused "victims" merely see tins of baby food brought by foreigners rather than encountering them in their local stores (having cleverly figured out the relationship between label and contents all by themselves), and to make sure we don't miss the obvious joke, we're told straight out that the shocked natives are CANNIBALS and the foreigners are MISSIONARIES! That's turning the tables, eh? Irony is so much funnier when you dispense with all that subtlety stuff, isn't it?

But that's not all — the same motif turns up again, this time with the onus of misunderstanding resting square on the shoulders of the "dumb foreigners" or illiterate adults right here in America:

In America, a Chinese family bought a can of what they believed — because of the picture on the label — to be fried chicken.

They were surprised and disappointed to open it and learn the can contained only the shortening used for cooking fried chicken.1

Some Hmong bought cans of Crisco believing that the label — a picture of golden brown fried chicken — depicted the contents.2

Adults who cannot read cannot look up phone numbers. In restaurants, they always order the house special. Their children's homework is a mystery. They buy cans of Crisco, thinking it's fried chicken, because that's what the picture on the label shows.3

Improbable as they may be, tales about the misconceptions of recent immigrants from other lands and cultures make some sense, but they don't hold up when applied to non-foreign illiterates (as in the last example above). Those who can't read may miss out on a great deal, but they don't grow up completely ignorant of the conventions of the societies in which they live. Even the illiterate know from experience that a red traffic light means "stop" (whether they drive or not), that a bottle with a skull and crossbones on its label contains something poisonous, and that fried chicken is not something one purchases in a can. Or are we supposed to believe that they also pick up cartons bearing pictures of cows from the dairy aisle, expecting to find not milk inside, but roast beef?

Even the illiterate know from experience that a red traffic light means "stop" (whether they drive or not), that a bottle with a skull and crossbones on its label contains something poisonous, and that fried chicken is not something one purchases in a can. Or are we supposed to believe that they also pick up cartons bearing pictures of cows from the dairy aisle, expecting to find not milk inside, but roast beef?

Satisfying the Hunger for Locally-made Baby Food in Senegal

By Abdoul Maiga

Last summer, my wife Sarah and I were preparing to move from France to Senegal for my new job as a communications officer for IFC. We had a lot to think about, with some of our concerns revolving around our then-seven-month-old baby daughter, Talia, including what we’d feed her in Dakar.

In France, we prepared Talia’s food with fresh organic products to make sure she was eating nutritious meals without additives. But knowing we’d have a million things to do after arriving in Senegal — and no time to make Talia’s food — we wondered what we’d find on the supermarket shelves in our new country.

Sarah turned to her social networks online to learn more about health and infant nutrition brands in Senegal. She soon discovered an organic Senegalese baby food called Le Lionceau, or Lion Cub, which parents were praising for being both organic and nutritious.

Soon after we arrived in Dakar last August, we went to the supermarket and found Le Lionceau and its many varieties: millet, fonio (a type of grain), sweet potato, moringa (a type of plant), ditakh (a type of wild fruit), bouye (baobab fruit), solom (a type of tamarind), papaya, mango, and niebe (black-eyed pea).

Le Lionceau’s display of baby foods at a supermarket in Dakar, Senegal. Photo courtesy: Le Lionceau

These were quite exotic flavors compared to Talia’s usual fare of spinach, leeks, and broccoli, and we wondered if she would like them. When we spooned some into her mouth, we soon had the verdict: A strong yes for these West African flavors!

We were relieved — and pleased — to have discovered a West African brand that was using local foods to produce quality products for local consumption.

The more jars we bought, the more curious I grew about the company. I wanted to know why and how the business started. What was the secret of its success? And could this business help inspire other small businesses in Senegal to harness the treasures of local agriculture?

A local focus

This last question was especially important for me. In far too many cases, West African raw materials — whether mined or grown — are shipped out of the region and refined elsewhere. In fact, less than 30 percent of Senegal’s agricultural products are processed locally. In 2019, Senegal imported nearly $770 million worth of consumer-oriented foods, mainly from the Europe and Asia. Imports constitute approximately 70 percent of Senegal’s food needs.

So I reached out to Siny Samba, a 30-year-old Senegalese native and co-founder and CEO of Le Lionceau, to learn more about her role in bucking this import trend. She told me she’d always been passionate about producing food. Earlier in her career, she had worked in France as an R&D engineer at Bledina, the baby food branch of French food multinational Danone.

Siny Samba, Co-founder and CEO of Le Lionceau, in Dakar, Senegal. Photo courtesy: Le Lionceau

One day, she had a life-changing idea.

“When I came back to Senegal on vacation, I noticed that 100 percent of the baby food in the stores was imported, even though we have very rich resources in terms of nutrition,” she said. “I felt that we were missing out on an opportunity.”

She believed that local fruits and grains could be processed in Senegal — for the benefit of babies as well as for local farmers. A few months later, Le Lionceau was born.

In 2018, she started the company with Rémi Filastò, a classmate from agricultural engineering school, with funding and support from Women Investment Club (WIC), Hub Impact Dakar, and more recently Investisseurs et Partenaires . Today, their company employs 20 people, and offers 15 varieties of organic baby puree, compotes, biscuits, and cereals. All are nutritious and support local agriculture value chains.

Le Lionceau’s employees labelling puree jars in Dakar, Senegal. Photo courtesy: Le Lionceau

Photo courtesy: Le Lionceau

The company, which has quadrupled its sales in the last three years, is planning to expand into Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, and Mali (my home country). Le Lionceau also hopes to feed African diaspora babies overseas through a pilot partnership with online retailers Amazon and C-Discount.

Partnering with farmers

Le Lionceau is still part of a very small group of food manufacturers in Senegal. One study in 2015 — the latest available — found that Senegal’s food processing industry consists of about 15,000 businesses that manufacture food products, but nearly 97 percent constitute mainly small-scale, informal operations. At the time, only about 20 companies were running large-scale operations using modern food manufacturing.

For Le Lionceau, expansion will include launching a high-end processing unit this year to boost production.

Researching and learning all of this — an effort sparked by a simple question about my daughter’s food — was inspiring. I hope Le Lionceau inspires other Senegalese entrepreneurs to pursue their dreams. As for Siny Samba, she credits her success to strong technical knowledge, hard work, and passion.

I hope Le Lionceau inspires other Senegalese entrepreneurs to pursue their dreams. As for Siny Samba, she credits her success to strong technical knowledge, hard work, and passion.

She also believes in the importance of strengthening the capacity of local farmers and working closely with them toward shared goals. This includes teaching them sustainable farming techniques to produce organic products and partnering with women’s cooperatives to work on raw materials pre-processing.

“The more you help build their capacities, the more efficient their yields are, and more markets can be created. Everybody wins,” said Samba.

Abdoul Maiga in Dakar, Senegal. Photo by Sarah Maiga

Our daughter Talia is now 14 months old. She is eating more solid foods, but we continue to buy Le Lionceau products, which she still loves.

We love it, too — the food has become a wonderful part of our move to West Africa.

Abdoul Maiga is an IFC Communications Officer for West and Central Africa in Dakar, Senegal.

Published in March 2022

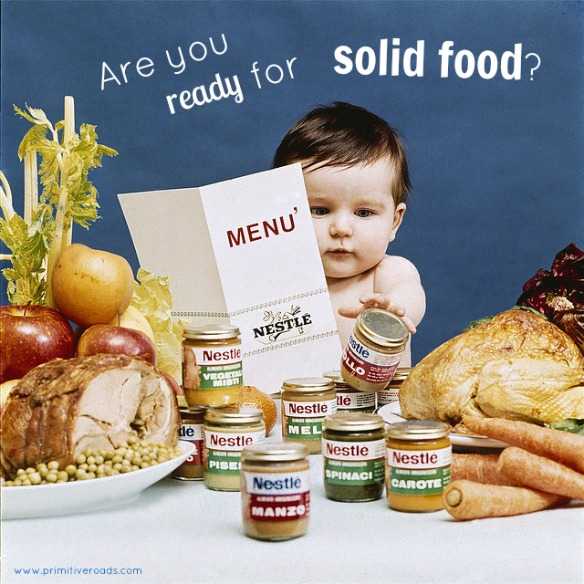

Every parent should know the baby food scandal

However, the infant formula market is still growing at $11.5 billion.

In 1974, "Baby Killer" exploded in the infant formula industry.

Social rights groups began to draw attention to the problem in the early 1970s.

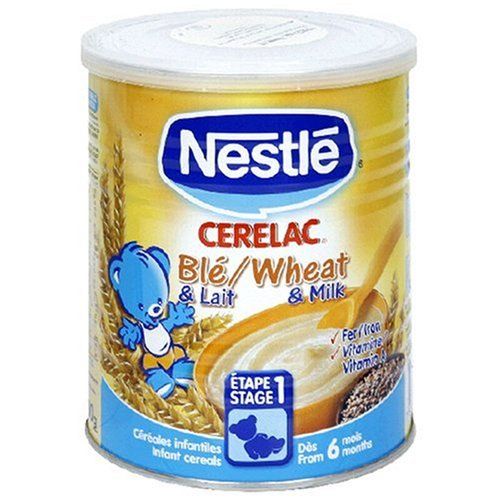

TheNewInternationalist published a 1973 exposé of Nestlé's marketing practices, entitled "BabiesMeanBusiness - Babies Do Business", which described how the company had made Third World mothers addicted to baby food.

But it was the "Baby Killer" booklet, published by London-based WarOnWant in 1974, that really set off the infant formula industry.

Nestl é blamed for Third World mothers addicted to formula milk

It doesn't matter that these women lived in poverty and struggled to survive.

In poverty-stricken cities in Asia, Africa and Latin America, "babies were dying because their mothers fed them Western-style bottled formula," says the War on Poverty.

According to the NewInternationalist, Nestlé did this in three ways:

• Creating a need where there was none.

• Convince consumers that their products are indispensable.

• Associating products with the most desirable and unattainable concepts - then providing a sample.

In the meantime, studies have shown that breastfeeding was more beneficial.

"At the same time, the benefits of breastfeeding were becoming known," Paige Harrigan, senior nutrition adviser at Save the Children, told BusinessInsider.

According to the State of the World report, vitamin A prevents blindness and reduces the risk of a child dying from common diseases, while zinc can prevent diarrhea. It is believed that six months of exclusive breastfeeding increases a child's chances of survival by six times.

However, the women of the Third World yearned for Westernization.

Poor women shifted from rural to urban lifestyles, which motivated them to stop breastfeeding and in turn spurred them into marketing, reports the War on Poverty:

"As women's social status changes and they go out to work . .. looking at the breasts as a cosmetic sex symbol rather than a food source reinforces this trend."

.. looking at the breasts as a cosmetic sex symbol rather than a food source reinforces this trend."

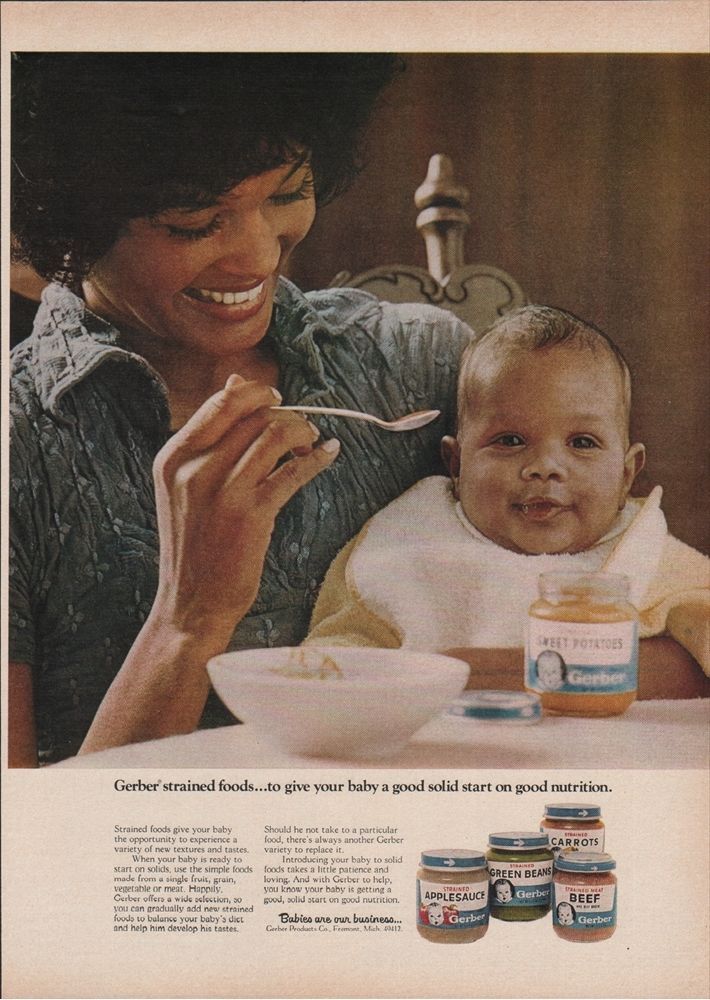

Young mothers everywhere received promotional materials for infant formula.

In addition to handing out brochures and samples to new mothers, companies hired “salespeople in nurse uniforms (sometimes qualified, sometimes not)” to come to their homes unannounced and sell them baby food, reports the War on Poverty. "

Here, a mother talks about Nestlé's "milk nurse" sales pitch:

"The nurse started by saying...breastfeeding is the best option. She then went into detail about the additional foods that a breastfed baby will need... this will avoid unnecessary problems.”

Source: BabyMilkAction

War on Poverty says it undermines women's confidence in breastfeeding.

Playing along with malnourished women's fear of harming their newborn was "a sure ploy," said the War on Poverty. When these women felt fear, pain, or sadness, their milk was lost as a result.

When these women felt fear, pain, or sadness, their milk was lost as a result.

"The oxytocin reflex, which controls the flow of milk to the mother's nipple, is an unconscious mechanism," the article says. "Somehow, mothers decide that a bottle is necessary for the milk she's giving... some mothers can be very, very concerned that they don't have enough milk."

Hospitals have also been accused of forcing mothers to use formula.

“It worked on two levels,” NewInternationalist said: In exchange for handing out “sample packs” of formula, hospitals received bonuses like formula and baby bottles.

"The most insidious of these is the free architectural maintenance of hospitals that build or renovate neonatal care facilities," the authors write.

In addition, according to the authors, "infant formula companies spend untold millions of dollars to subsidize office furniture, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications, and medical professional travel. "

"

Meanwhile, in third world countries, women were trying to save money by diluting the formula.

Formula had to be diluted with water, but Third World mothers did not realize that excessive dilution, especially with contaminated water, could “prevent the baby from absorbing the nutrients from food and lead to malnutrition,” says the War Against poverty."

A NewYorkTimes article about the scandal stated that one Jamaican family "averaged only $7 a week", resulting in a mother diluting three times the recommended amount with water so she could feed two children.

Millions of babies have died of malnutrition.

"The results can be seen in clinics and hospitals, slums and cemeteries of third world countries," says the War on Poverty statement. "The emaciated bodies of children, all that's left is a big head on the shriveled body of an old man."

In The Times, US Agency for International Development spokesman Dr. Stephen Joseph blamed the use of infant formula for millions of infant deaths each year due to malnutrition and diarrheal disease.

Stephen Joseph blamed the use of infant formula for millions of infant deaths each year due to malnutrition and diarrheal disease.

It also hindered the growth of babies in general, notes the War on Poverty. Referring to the "complex links that exist between breastfeeding and emotional and physical development," the group noted that breastfed babies walked "significantly better than bottle-fed babies" and were more emotionally developed.

In 1974, Nestl é sued War on Poverty for defamation.

Nestlé was not going to take these accusations lightly. The company has sued the German author of the debunking translation of "War on Poverty" who published an article in Sweden titled "Nestlé kills children".

Nestlé won the lawsuit in 1976, BabyMilkAction reported, but with a caveat: the judge urged them to "revolutionize the way they advertise." TimeMagazine declared it a "moral victory" for consumers.

Negative publicity sparked a global boycott Nestl é.

The Infant Formula Coalition has announced a boycott in the US against Nestlé. It soon spread to France, Finland, Norway and many other countries.

“I remember my mother telling me about this, and in 1980 she refused to buy candy bars because we heard on the news about so many children dying,” Harrigan said.

The boycott was suspended in 1984 but resumed in the late 1980s when Ireland, Australia, Mexico, Sweden and the United Kingdom adopted it.

Source: BabyMilkAction

The International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was established in 1981.

In 1978, Senator Edward Kennedy held a series of US Senate hearings on unethical marketing practices. This was followed by international meetings involving the World Health Organization, UNICEF and International Baby Nutrition Action Network.

By 1981, the 34th World Health Assembly adopted resolution WHA34.22, which includes the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

The Code explains how baby food should be promoted worldwide.

The Code states that baby food companies cannot:

• Promote products in hospitals, stores, or to the general public.

• Give free samples to mothers

• Give gifts to healthcare workers or mothers.

• Provide misleading information

“The biggest one was explaining the cost of using the mix,” Harrigan said.

Social rights groups say baby food companies still don't follow the rules of the Code.

To this day, Nestlé is being studied by citizens and NGOs around the world. Publications such as IBFAN's "Breaking the Rules, Stretching the Rules" describe violations ranging from posting posters of healthy formula-fed babies in hospital wards to issuing promotional prescription pads to doctors.

But Harrigan says it's hard to track if countries are following the Code. “In some places the Code may be law, but often its enforcement is weak. The next step will be to determine if the Code is law and how to enforce it in a systematic way.”

BabyMilkAction, a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting breastfeeding and exposing conflicts of interest, created this "Nastie" logo for Nestlé mockumentation in 2010.

Celebrities such as this British TV presenter joined the breastfeeding cause in the 1990s.

Nestlé's British show "The Mark Thomas Product" rocked Nestlé in 1999 when its host asked company executives why they didn't have all the information on their product labels in English. Haven't the poor and the illiterate taken advantage of this?

Here (pictured) Mark Thomas asks why the "mozambique baby milk can" is not signed in Portuguese, the country's official language.

According to BabyMilkAction, Emma Thompson called for a boycott of the Perrier Comedy Award in 2001 because the drink belongs to Nestlé. Tap water awards were established the following year.

Tap water awards were established the following year.

Breastfeeding and formula remain a hot topic today.

New York Mayor Bloomberg recently launched the LatchOn, NYC initiative to end formula in hospitals.

"As far as I can tell, he uses a lot of the Code," Harrigan said.

Even your kitchen is not safe...

breastfeeding-and-formula-remain-a-hot-topic-16

Jill Krasny

Jun 25 2012 ://www.instagram.com/prolactin_gv

Editor: Anastasia Afanasyeva, https://www.instagram.com/cirilla_emgirovna

Memories of the Nestlé infant formula scandal that rocked the 1970s

However, faced with a declining population in the Western world in the 1960s , mix sales fell. Infant formula companies had to find a new market for their product. Some companies, such as Nestlé, have reached out to developing countries by providing mothers with promotional materials and samples to teach them the new method of feeding their babies.

However, Nestlé infant formula has had a terrible impact on Africa, South America and South Asia. The number of lives lost associated with Nestlé infant formula skyrocketed, leading to a boycott of the Nestlé company in the 1970s. The boycott did not end the problem, but rather spurred the call for international standards for infant formula.

An even more recent "water scandal" in Africa is reminiscent of the Nestlé infant formula predicament. Both of these stories prove that corporate interests, namely making money, often win over elementary human concern.

Nestlé sued the publisher for claiming "Nestlé kills babies" and won

The first noteworthy article on Nestlé's methods of distributing infant formula in third world countries was published in the New Internationalist in 1973 year under the title "Children are business". The article accused Nestlé of three things when it came to their business practices in third world countries:

“Creating a need where there was none.

Convince the consumer that our product is indispensable.

Associate a product with the most desirable and unattainable concepts - and then provide a sample.

The 1974 British edition of The Baby Killer pamphlet was another tool that sparked the worldwide debate about infant formula. When a German publisher translated the booklet, changing the title to Nestlé Kills Children, Nestlé sued for defamation. The parties spent two years in litigation, and in the end Nestlé won the lawsuit. However, the judge convinced Nestlé to adjust the advertising and publications.

Nestlé saleswoman disguised as a nurse told mothers about the benefits of infant formula .

These so-called "milk nannies" visited homes and hospitals to talk about their innovative formulas, and while some of them may have been educated, most of them were not. They spent time in maternity hospitals giving advice on nutrition and feeding, as well as giving mothers instructions on how to prepare infant formula.

In Singapore, milk nannies were so widespread that they were banned from visiting hospitals. As a result, these nannies simply waited outside for the new mothers to come out and then provided samples of infant formula.

In Jamaica, milk nannies could get the names of new mothers and visit their homes. In the Philippines, milk nannies visited government housing, finding homes with newborns and young children by diapers hanging from clotheslines.

Mothers reduced the nutritional value of infant formula by diluting it with water

When mothers became dependent on infant formula, the cost of the product became a problem. As a result, many women have begun to dilute the mixture so that it lasts longer. They added three times the recommended amount of water, which seriously reduced the nutritional value of the mixture.

When researchers in Indonesia studied this phenomenon, they found that "only one in four women diluted the mixture close enough to the recommended concentration. " At a meeting of the Health and Research Committee held in the United States on 19In 1978, Dr. Alan Jackson testified that mothers "stretched" cans of formula, which should have lasted three days for one child, up to two weeks while feeding two children the contents of one can.

" At a meeting of the Health and Research Committee held in the United States on 19In 1978, Dr. Alan Jackson testified that mothers "stretched" cans of formula, which should have lasted three days for one child, up to two weeks while feeding two children the contents of one can.

Babies in developing countries made sick by contaminated water

Mothers in developing countries used water containing faecal organisms, among other contaminants, when mixing formula. When a Peruvian nurse named Fatima Patel testified before a U.S. subcommittee at 1978, she shared how difficult it would be to find clean water for infant formula:

"The river is used as a laundry, as a bathroom, as a toilet and as a source of drinking water ... also we can say ... to get fuel for boiling of this water, the woman must go into the jungle, cut down the trunk of a tree with a machete ... and bring it on her back. No mother would use this hard-earned piece of wood to boil water. Thus, babies drink contaminated water."

Thus, babies drink contaminated water."

In addition, the bottles used for formula have not been sterilized. Despite labels on formula jars and instructions from milk nannies, women often lacked heating methods sufficient to sterilize bottles - alternatively, a few people could only access one pot, resulting in insufficient resources to properly sterilize a bottle. .

Nestlé attracted mothers and babies with free samples

Nurses distributed free samples of formula to new mothers, giving them the option to either stop breastfeeding or use formula in combination with breastfeeding.

However, when the baby is breastfed less or stops suckling, the mother's milk gradually dries up. This led to an inevitable dependence on formula milk.

Although financial dependence was significant, equally important was the lack of nutrients and antibodies that infants received from breast milk. Scientists have recognized the importance of colostrum, a milk-like substance produced by a mother shortly after a baby is born, in building a baby's immune system. As infants began to breastfeed less, the overall health of infants in third world countries began to deteriorate.

As infants began to breastfeed less, the overall health of infants in third world countries began to deteriorate.

WHO and UNICEF linked infant mortality to infant formula started collecting data.

They found that millions of babies were dying from malnutrition and diarrhea caused by diseases such as kwashiorkor (a type of severe malnutrition) and alimentary insanity (alimentary dystrophy) caused by protein deficiency. Doctors have linked these ailments to the increased use of infant formula. Due to the growing reliance on infant formula, babies' immune systems were less able to develop, fight disease, and allow the baby to survive infancy.

Doctors have even coined the term "weaning diarrhea", defined as "a collection of illnesses in an infant described as a weaning syndrome". This is due to the introduction of other foods and the loss of the protective properties obtained with breast milk.

Formula companies made mothers question their own ability to care.

Formula companies used the so-called "confidence trick" to tell mothers that they should be aware of the possibility of their babies being malnourished. This tactic will create fear or anxiety in mothers and make them question their ability to produce enough breast milk for their babies and encourage mothers to start using formula as an alternative. As a result, their breast milk gradually dried up.

Mothers in developing countries, especially in the 60s and 70s, had little doubt about their ability to breastfeed until they had an alternative. As soon as the mother stopped breastfeeding, even temporarily, she was forced to feed her baby with formula milk.

As the pamphlet Baby Killer puts it, "Somehow mothers decide that a bottle is necessary for the milk she gives ... some mothers may even be so concerned about not having enough milk that they won't have any." .

Western culture bombarded women with marketing in the 1970s

Another key element in the transition from breastfeeding to formula feeding in developing countries was the advertising of Nestlé and other formula manufacturers. Many women moved to the cities in the 1970s, where they were bombarded with messages, both overt and covert, that bottle-feeding was both modern and "Western."

Many women moved to the cities in the 1970s, where they were bombarded with messages, both overt and covert, that bottle-feeding was both modern and "Western."

Both print and broadcast media in developing countries such as Brazil "where infant formula was the most advertised product after cigarettes and soap ... promised, albeit subtly, that formula was a modern method of infant feeding associated with mobility, and that she would produce plump-cheeked children."

Companies bribed clinics and hospitals with free food and financial incentives

In many developing countries, Nestlé and other dairy companies supplied clinics and hospitals with large amounts of formula every year. This encouraged institutions to pass on the formula to their patients, but also attracted the medical community to the corporate plan.

In Nigeria, clinics received up to "8,000 free cans of infant formula annually." In Ethiopia, India and other parts of the world, companies have also given free bottles and other gifts to clinics and hospitals to encourage breastfeeding. Still later, formula companies began donating large sums to hospitals and physicians, with the companies spending "untold millions of dollars to subsidize office furniture, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications, and medical professional travel."

Still later, formula companies began donating large sums to hospitals and physicians, with the companies spending "untold millions of dollars to subsidize office furniture, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications, and medical professional travel."

Infant formula companies set the standard for formula in the early 1980s

In 1980, the World Health Assembly adopted WHO and UNICEF recommendations on international infant feeding practices. Although they released an official code the following year, Nestlé and three other companies publicly stated their unwillingness to follow any official policy.

In the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes adopted by the World Health Assembly at 1981, stated that baby food companies should not have direct contact with mothers, hospitals or health care workers - especially with gifts - they should not provide misleading information and their product labels should be clear and contain appropriate warnings. Companies also had to explain the costs of using mixtures. Countries around the world began to adopt the Code, and companies soon agreed. In the end, Nestlé agreed to follow the Code at 1984 year. However, this policy has hardly been enforced and companies continue to break and break the rules.

Companies also had to explain the costs of using mixtures. Countries around the world began to adopt the Code, and companies soon agreed. In the end, Nestlé agreed to follow the Code at 1984 year. However, this policy has hardly been enforced and companies continue to break and break the rules.

The worldwide boycott of Nestlé began in 1977 and continued until 1984.

In the 1970s, the personal is political movement brought renewed attention to breastfeeding on a global scale. The 1970s saw increased concern about women and babies in Third World countries, where breastfeeding had declined significantly over the previous decade.

Researchers studied this and the associated rise in bottle feeding, eventually finding that not only did misuse of infant formula lead to infant illness and death, and that mothers were being misled about the effectiveness of formula. The study resulted in a boycott of Nestlé, which had "81 factories in 27 developing countries and 728 sales centers in all parts of the world promoting their products. "

"

In the United States the Infant Formula Action Coalition announced a boycott that quickly spread to parts of Europe, Canada and Australia. Between 1977 and 1981, the Nestlé company tried to solve problems and restore its image; meanwhile, the International Infant Food Surveillance Network (IBFAN), a group of six anti-Nestlé organizations, formed and fought to oversee the infant formula industry.

Although International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was adopted in 1981, Nestlé did not agree to follow it until 1984. This boycott ended.

The boycott resumed in the late 1980s and continues to this day

The Nestlé boycott was renewed in 1988. Since then, more than 20 countries have boycotted Nestlé's subsidiaries due to their persistent attempts to circumvent International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes . The non-profit organization Baby Milk Action insists that the boycott will continue until Nestlé agrees to follow their four-point action plan.

Nestlé has a policy of its own but continues to face allegations of selling "low-quality" infant formula in South Africa. In February 2018, Nestlé was accused of not including important ingredients in its product in South Africa, as well as of "a strategy to increase profits by trying to convince parents to buy more expensive products, believing that they are better for their child's health."

Nestlé also caused Fanta Syndrome

Infant formula is not the only product that major Western companies have introduced in less developed countries that has had detrimental health effects. At 1974 in Africa was diagnosed with "Fanta Syndrome", named after the orange carbonated drink Coca Cola. The lack of suitable alternatives to baby food, as well as a misunderstanding of the product's intended purpose, only exacerbates the problem.

Nestlé has also become embroiled in a water dispute. The company has been accused of selling Pure Life water to countries in dire need such as Pakistan and Nigeria, but making it too expensive for most consumers, proving once again that profit, not care, is the world's greatest driving force.