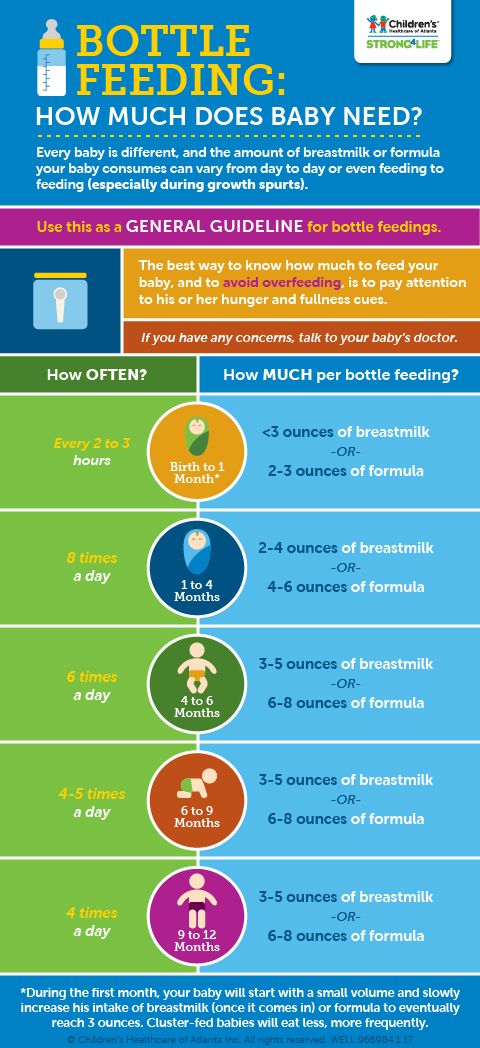

Feed baby when hungry or on schedule

Why feeding "on cue" benefits babies

© 2009 – 2021 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

The infant feeding schedule reconsidered

In the past, Western “baby experts” often instructed parents to feed their babies at regularly-spaced intervals of 3- or 4-hours. Today, official medical recommendations have shifted in favor of letting babies decide. Why the change?

There are a number of reasons, but the simple answer is this: When we let babies determine the timing and the length of their own feeds, they are more likely to get what they need: Not too little, and not too much.

It begins in the newborn period. If newborn babies aren’t fed frequently enough, they are at higher risk for dehydration and underfeeding. So the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advises parents to feed infants at least once every 2-3 hours — whenever babies show signs of hunger (AAP 2015).

During the subsequent months, babies may be able to go longer between meals. But feeding responsively — on cue — remains the ideal approach.

- It can help breastfed babies adjust to natural variations in milk quality (Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences 1991).

- It can help bottle-bed babies avoid overfeeding.

- And it can help any infant cope with the challenges of getting enough to eat during a growth spurt.

All babies experience fluctuations in their energy requirements. Feeding on cue makes it easier for infants to increase or decrease their intake as needed (Tylka et al 2015).

That’s probably why responsive feeding is associated with healthier growth trajectories in babies (Chen et al 2020; Fuglestad et al 2017).

And that’s not all. Research hints that responsive feeding benefits babies in additional ways. It might affect an infant’s emotional functioning. It might support better cognitive outcomes.

So it seems that the best infant feeding schedule is the one that babies devise for themselves.

But what is the evidence? Let’s take more detailed look.

The infant feeding schedule in evolutionary perspective

Mammal babies everywhere begin life on a diet of milk. But they don’t all time their feedings in the same way. In some species, mothers “park” or “cache” their young in nests, and leave them there.

It’s a strategy that allows the mother to go foraging without the fuss of a tag-along infant. But it only works if there’s a way to keep the babies from starving during those long separations. How do they cope?

The solution is two-fold.

1. Mothers produce milk that is high in fat, and high in protein — what we might call super-fuel.

2. Infants have the ability to suckle very fast and efficiently when they finally get to feed.

Together, these elements permit babies to “tank up” on a highly-concentrated food–enough to last them for many hours.

Mammals that follow this strategy are called “spaced feeders,” and their milk is very rich indeed.

A good example of a spaced feeder is the rabbit, which produces milk that is 18.3% fat and 13.9% protein (Jenness 1974).

By contrast, other mammals keep their babies with them as they forage. Exactly how they do this varies from species to species. Some, like monkeys, carry their babies. Others, like cows, have their infants follow them around on foot.

But regardless, the babies stay close, and along with proximity comes frequent meals. Babies tend to initiate feedings, and suckle at a more leisurely rate. They don’t need to tank up on a super-fuel, and so their mothers don’t make one. The milk is less caloric, more dilute.

A good example of a continual feeder is a cow, which produces milk that is typically 3.7% fat and 3.4% protein (Jenness 1974).

What about humans?

In some modern, industrial societies, humans act like spaced feeders. Babies are “parked” in cribs or cradles and get fed after intervals of 3-4 hours.

But were we designed for this strategy?

Does the biology of human breastfeeding have the earmarks of spaced feeding?

The answer is no because

- human milk is relatively low in fat (3.

8%) and protein (1%), and

8%) and protein (1%), and - human infants suckle at the slow pace typical of continual feeders.

So our basic physiology gives us away. We don’t produce super-fuel, and our infants lack the spaced-feeder’s knack for super-fast milk extraction. And that’s consistent with the behavior of other members of our family tree. Continual feeding is the strategy of choice among all of our close relatives — including bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas.

It is also the strategy observed among human beings living in traditional societies.

In hunter-gatherer societies, babies aren’t just nursed on cue. They are also nursed very frequently — about 2-4 times an hour (Konner 2006).

In other traditional societies, parents don’t match this extreme pace, but feedings are nonetheless initiated by the infants.

In a survey of non-industrial societies (which included nomadic pastoralists and settled agricultural peoples) anthropologists found that “on demand” feeding was the rule. In every society for which information about the infant feeding schedule was available (25 out of 25), people fed their infants on cue (Severn Nelson et al 2000).

In every society for which information about the infant feeding schedule was available (25 out of 25), people fed their infants on cue (Severn Nelson et al 2000).

This, then, is our basic physiology and our evolutionary heritage. But how much does it matter? Is this something we can work around?

Mightn’t we be able to keep babies equally happy and healthy using a strict infant feeding schedule? Perhaps it’s just a matter of tweaking the timing of feeds.

It sounds straightforward, but there are stumbling blocks.

Babies vary in their needs — from individual to individual, and from day to day

Different babies have different needs, and the same baby experiences fluctuations in energy requirements over time.

What if your baby has the urge to be more active, and needs more food to fuel her activities?

What if your infant needs more fluids because it’s hot, or because he’s coming down with a virus?

What if your baby is in the middle of a growth spurt?

It isn’t merely that you need to adopt a schedule that is individualized to your baby’s current needs. You also need a schedule that keeps changing in response his or her future needs.

You also need a schedule that keeps changing in response his or her future needs.

That’s pretty hard to do unless you are paying attention to your baby, offering meals when you observe signs of hunger. And if you are doing that, you aren’t imposing a strictly-timed infant feeding schedule. By definition, you are feeding on cue.

Moreover, the baby’s need for food and fluids is only one side of the equation — the demand side. There is also the supply side of the equation. If your baby is on formula, it’s easy to figure out what your baby is being supplied with. You can read the label, and know your baby is getting the same formulation from one feed to the next.

But breast milk doesn’t work that way. Human breast milk is roughly similar in composition from one woman to the next, but there are significant differences. Not only does breast milk vary between individuals. It also varies between milk samples produced by the same woman at different points in time.

Breast milk varies in caloric content

When Shelly Hester and her colleagues analyzed 22 published studies on the metabolizable energy content of breast milk, the researchers were able to estimate the calories found per serving: About 65 calories per 100 milliliters (mL) of breast milk.

But hang on. That estimate is the average for milk expressed between 2 weeks and 6 weeks postpartum (Hester et al 2012).

Milk produced earlier is substantially less caloric. Colostrum, the milk produced during the first few days, has only about 53 calories per 100 mL. Then, between approximately 6 and 14 days postpartum, the caloric density increases slightly, averaging 58 calories per 100 mL (Hester et al 2012).

And milk produced later — after the 6 weeks postpartum — becomes increasingly caloric as time goes by. That’s because the fat content of breast milk tends to increase the longer a woman continues to nurse.

When researchers have tracked lactating mothers over time, they’ve found that the fat content in milk produced at 6 months is higher than it is at 3 months (Szabó et al 2010).

That’s a lot of variation already, but we’ve only scratched the surface because individual mothers vary substantially in the energy content of their milk. Studies indicate that individual woman may range widely in the fat content of their milk — from 2 grams per 100mL to 5 grams per mL (Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences 1991).

And other research has identified some of the causes of this variation: Diet, body mass index, maternal age, socioeconomic status, and even smoking habits have been linked with differences in the amount of fat in breast milk (Daniel et al 2021; Innis 2014; Rocquelin et al 1998; Argov-Argaman et al 2017; Al-Tamer et al 2006; Agostoni et al 2003).

So it shouldn’t surprise us if there is no “one size fits all” infant feeding schedule that’s going to serve every baby equally well. Babies vary in their needs, and different breastfed babies may be receiving very different types of breast milk. Some get milk that is richer than average. Others get milk that is much lighter.

Others get milk that is much lighter.

And since babies can only drink so much before their stomachs are full, the fat content of milk is going to make a substantial difference in the calories they obtain from any given feeding session. Some babies will need more frequent feedings than other babies do, simply because their milk has fewer calories per serving.

Just as important, milk from the same mother can fluctuate in quality from day to day, and even from hour to hour (Khan et al 2013). So it’s possible that an infant feeding schedule that works pretty well one day might leave a baby dissatisfied on another.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the quality of breast milk changes during the course of a feed.

At the beginning of a feeding session, when the breast appears full, the milk that is released is relatively diluted and low in fat. Then, as the session continues, the breast takes on a softer, emptier appearance, and the milk changes.

The earlier “foremilk” gives way to a more concentrated, fattier “hindmilk” (Woolridge 1995), and you can see the difference in this photo.

The foremilk looks watery and bluish. The hindmilk — produced by the same breast, but later in the session — is ivory in color, and thicker.

Thus, if the adult terminates the breastfeeding session too soon, or forces a baby to switch breasts too soon, the baby will miss out on hindmilk (Woolridge and Fisher 1988).

Babies in this situation will fill up on a low calorie meal, and require more frequent feedings to obtain the energy they need.

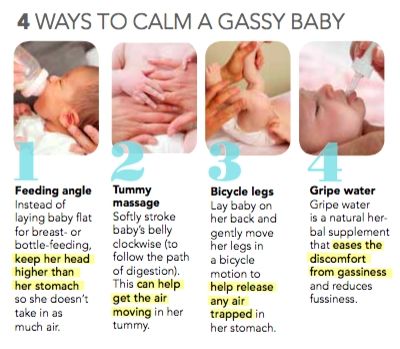

In addition, they may be at higher risk for symptoms associated with consuming low quality milk. As breastfeeding expert Michael Woolridge (MD and PhD) has pointed out, low-fat milk can contribute to colic, vomiting, diarrhea, and flatulence in infants (Woolridge 1995).

What about formula-fed babies? Don’t they need us to impose restrictions — so they won’t overfeed?

You may have heard about research linking formula-feeding with rapid infant growth and an increased risk of childhood obesity. The links have been replicated in many studies, have prompted concern. Why are formula-fed babies more likely to become overweight?

The links have been replicated in many studies, have prompted concern. Why are formula-fed babies more likely to become overweight?

One answer is that formula might be too energy-dense for some babies (Hester et al 2012). But it also appears that the delivery system — drinking from a bottle — is a contributing factor.

For example, in one study of 1250 American infants, researchers found that bottle-feeding in early infancy was associated with a tendency to eat everything on offer, regardless of whether the babies consumed formula or breast milk.

The more frequently babies drank from bottles during their first 6 months, the more likely they were to become big eaters later. As toddlers, they were more likely to completely drain any bottle or cup given to them (Li et al 2010).

A smaller study conducted in the United Kingdom reports similar results (Brown and Lee 2012).

It’s not clear what this means, but we know that infants can extract milk more quickly from a bottle than they can from a breast.

Perhaps the fast pace leads to consuming more during a feed, so babies become accustomed to taking in bigger meals.

Whatever the underlying cause, it invites the obvious question: Isn’t this a good reason to impose an infant feeding schedule? Aren’t bottle-fed babies better off if we restrict the timing of their meals?

The evidence suggests not.

For instance, experimental research indicates that babies are sensitive to internal cues of hunger and satiety. When allowed to feed on demand, both breastfed (Woolridge and Baum 1992) and formula-fed (Fomon et al 1975) infants adjust their intakes in response to the caloric content of their milk or formula.

And when researchers have tracked infant development over time, they haven’t found that feeding restrictions — including timed feeding schedules — reduce the risk of a child becoming overweight. On the contrary.

In one study, researchers found that scheduled feeding was a risk factor for rapid weight gain (Mihrshahi et al 2011). And — overall — research suggests that restrictive feeding is more likely than responsive feeding to lead to high weight gain (Gubbels et al 2011; DiSantis et al 2011b; Dinkevich et al 2015; Gross et 2014; Spill et al 2019).

And — overall — research suggests that restrictive feeding is more likely than responsive feeding to lead to high weight gain (Gubbels et al 2011; DiSantis et al 2011b; Dinkevich et al 2015; Gross et 2014; Spill et al 2019).

Surprising? Perhaps it shouldn’t be. These observations are consistent with studies of older children.

It appears that intrusive, restrictive rules about eating may interfere with the development of self-regulation. They may actually increase a child’s tendency to engage in emotional overeating (Jani et al 2015; Rodgers et al 2013), and lead to excessive weight gain (Tylka et al 2015).

So researchers suspect that imposing restrictions — like a strict infant feeding schedule — are counterproductive for preventing obesity.

Kids might learn to ignore their own hunger cues, and eat in response to social cues (“it’s time!”) or emotions (“I’ve been denied — now it’s time to make up for that”). By allowing infants to initiate feedings, we may be helping them develop a more healthy relationship with food.

Other considerations: Do the effects of an infant schedule extend beyond matters of nutrition and energy regulation?

That’s an interesting question.

From birth, infants get distressed when their signals to nurse are ignored. And studies indicate brief, token acts of feeding can help newborns bounce back from stress.

Newborns cry less and show signs of reduced pain when they receive small amounts of milk, formula, or sucrose (see review by Shaw et al 2007; also Blass 1997a; Blass 1997b; Blass and Watt 1999; Barr et al 1999). The act of suckling is itself an analgesic (Blass and Watt 1999). And breastfeeding may be a painkiller and stress-reducer.

In one study, newborns subjected to a painful blood collection procedure cried much less if they were permitted to breastfeed (Gray et al 2002). They cried just 4% of time total procedure time, versus 43% for infants in a control group.

Babies who fed during the procedure also showed markedly reduced rates of grimacing (8% v. 50%), and their heart rates increased less (6 beats per minute v. 29 beats per minute).

50%), and their heart rates increased less (6 beats per minute v. 29 beats per minute).

Some of these differences may be attributable to the extra skin-to-skin contact that the breastfed babies got. But in a follow-up study, the researchers confirmed that breastfeeding was more soothing than skin-to-skin contact alone (Gray et al 2000; Gray et al 2002). And the authors noted that babies who were held without being fed tended to get frustrated, and required much more time to settle down (Gray et al 2002).

So what might happen to a baby who finds that her signals for quick comfort are routinely ignored?

While I’ve found no studies that bear directly on this question, responsive care has been linked with development of better stress regulation skills — even among highly irritable, “at risk” babies.

Moreover, a variety of studies suggest that sensitive, responsive parenting contributes to secure attachment relationships and better child outcomes.

And there is intriguing research regarding cognitive development.

In what is perhaps the largest study yet to investigate the effects of an infant feeding schedule, Maria Iacovou and Almudena Sevilla (2013) tracked the development of more than 10,000 British children — breastfed and bottle-fed alike — from birth to age 14.

There were no experimental manipulations. The researchers merely noted whether babies had been fed on schedule or “on demand”, and then followed their cognitive and academic progress. And the results? They favored feeding “on demand”.

At every age, kids who’d been subjected to an infant feeding schedule performed more poorly on standardized tests. Moreover, their IQs were, on average, 4.5 points lower.

Correlation doesn’t prove causation, of course, and this is just one study. It needs to be replicated.

But it’s interesting to note that the study’s results remained much the same even after researchers controlled for a variety of potential confounds, like parents’ education levels, economic factors, health, breastfeeding, maternal smoking, and the children’s exposure to negative discipline tactics.

There wasn’t any obvious reason for the difference between groups. Just the distinction between feeding on cue and following an infant feeding schedule.

Summing up: What do we really know?

As with most science, we still have a lot left to learn.

We don’t yet understand all the determinants of breast milk quality, or why the composition of breast milk changes over time.

We don’t yet understand all the causes of increased obesity risk in formula-fed and bottle-fed infants.

And it isn’t yet clear how much impact an infant feeding schedule might have over the long-term. In particular, we need more research on the possible effects an infant feeding schedule might have on stress regulation and cognitive development.

Meanwhile, what we do know is that human beings exhibit the characteristics of continual feeders, and it’s a sure bet that relatively frequent, “on demand” feedings have been the historic and evolutionary norm for our species.

It’s also clear that breast milk can vary substantially in fat composition and caloric density, so that babies will benefit from being able to schedule the timing of their own feeds.

And all babies — whether they consume breast milk or formula — experience fluctuations in their needs for fluids and energy. When we are responsive to their cues of hunger and thirst, we’re more likely to meet these needs.

More reading

How can you tell if a newborn is hungry? Find answers to this and other questions in my article, “The newborn infant feeding schedule: A review of the evidence against regimented feedings.”

In addition, you can read more about this topic in “Breastfeeding on demand: A cross-cultural perspective.” And for more information about the composition of breast milk, read this Parenting Science article.

Wondering if you can time your baby’s meals to optimize sleep at night? Check out my article, “Dream feeding: An evidence-based guide to helping babies sleep longer.”

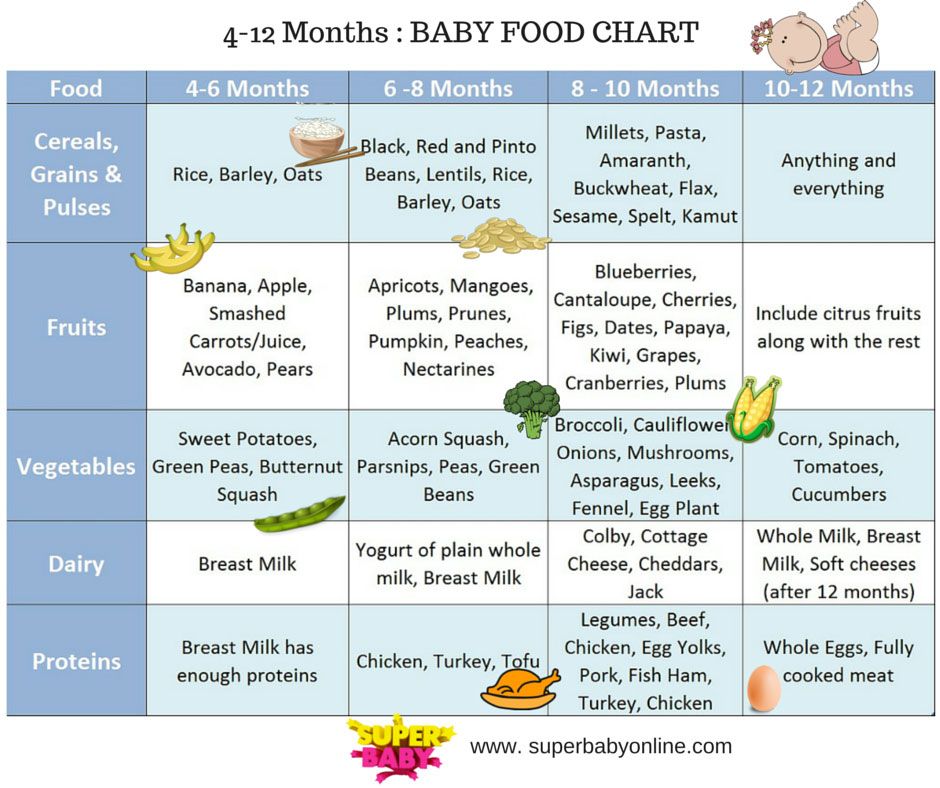

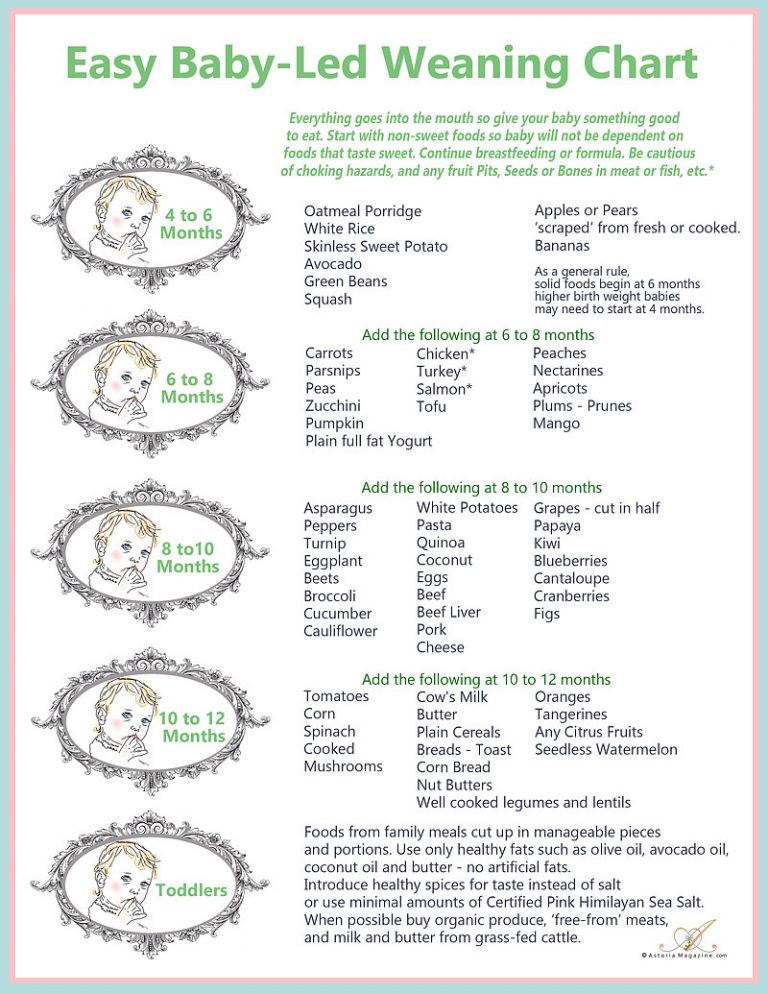

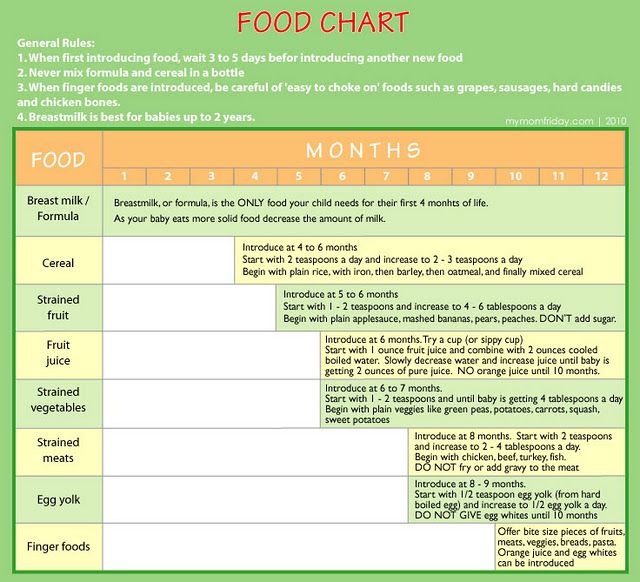

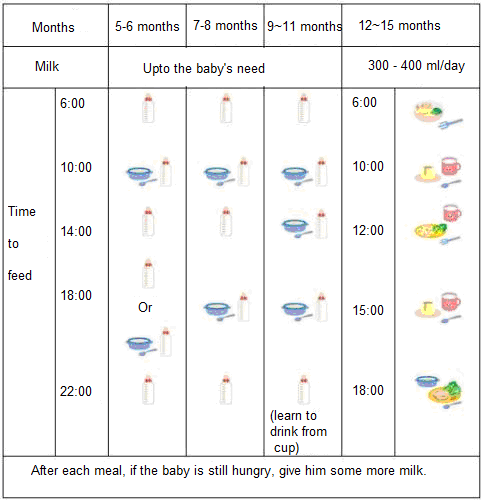

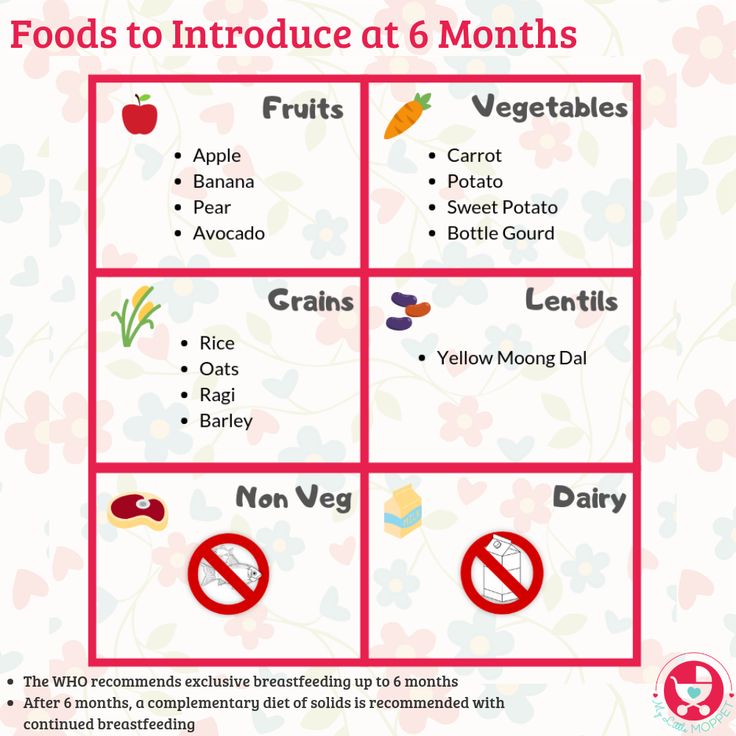

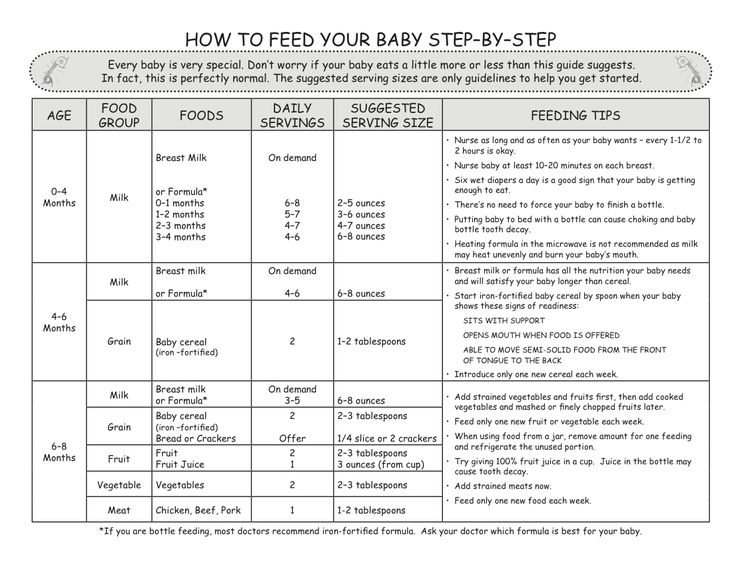

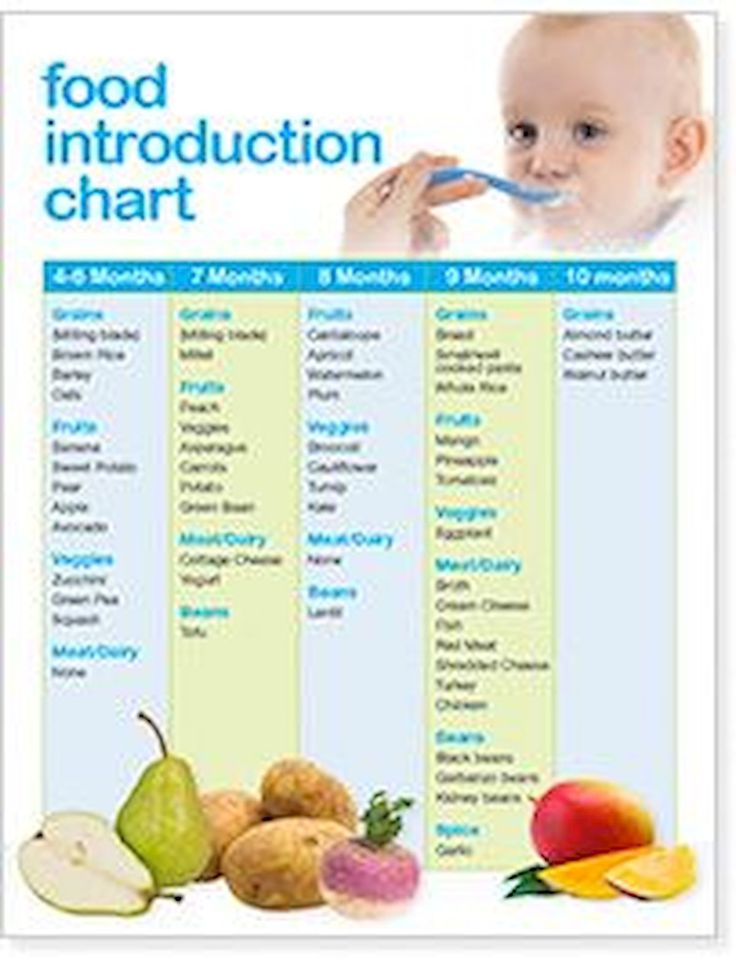

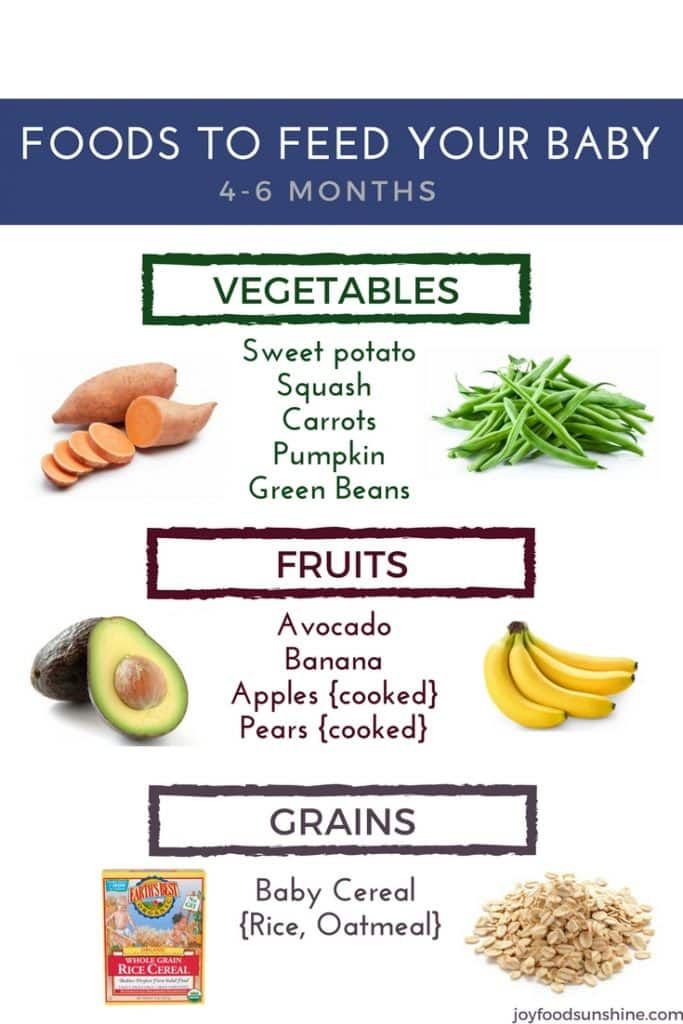

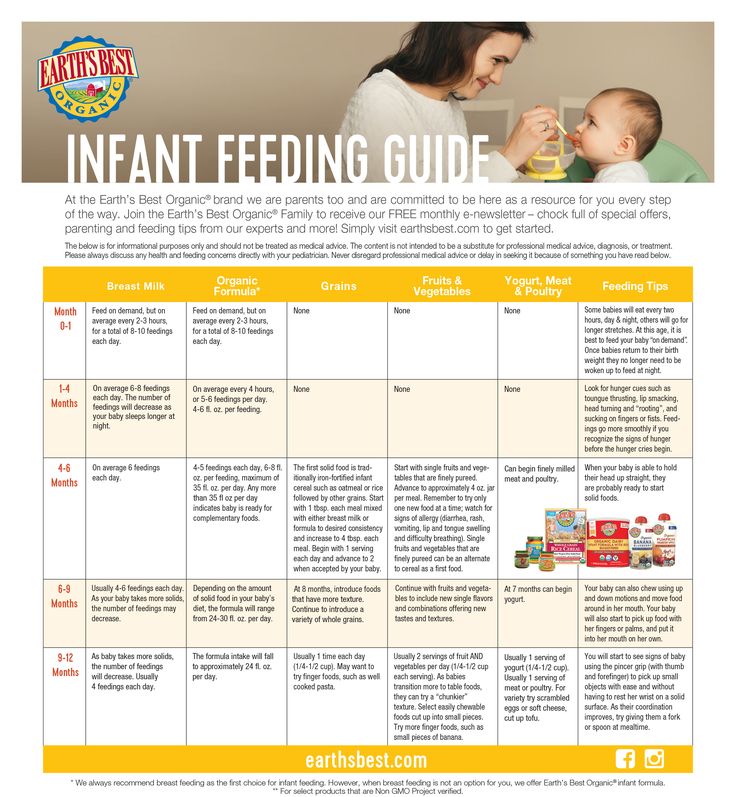

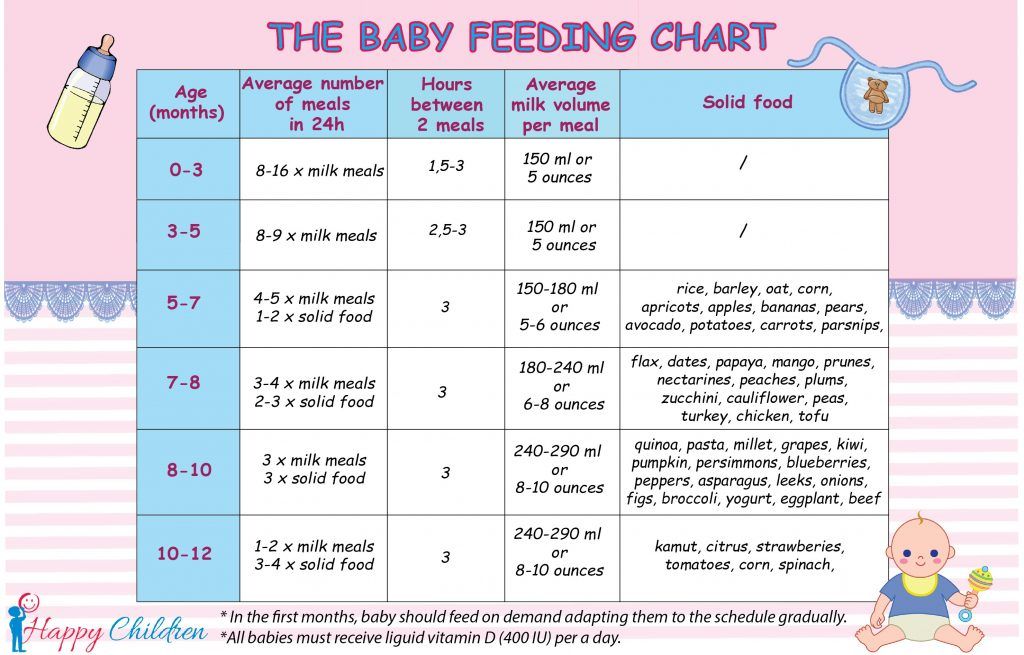

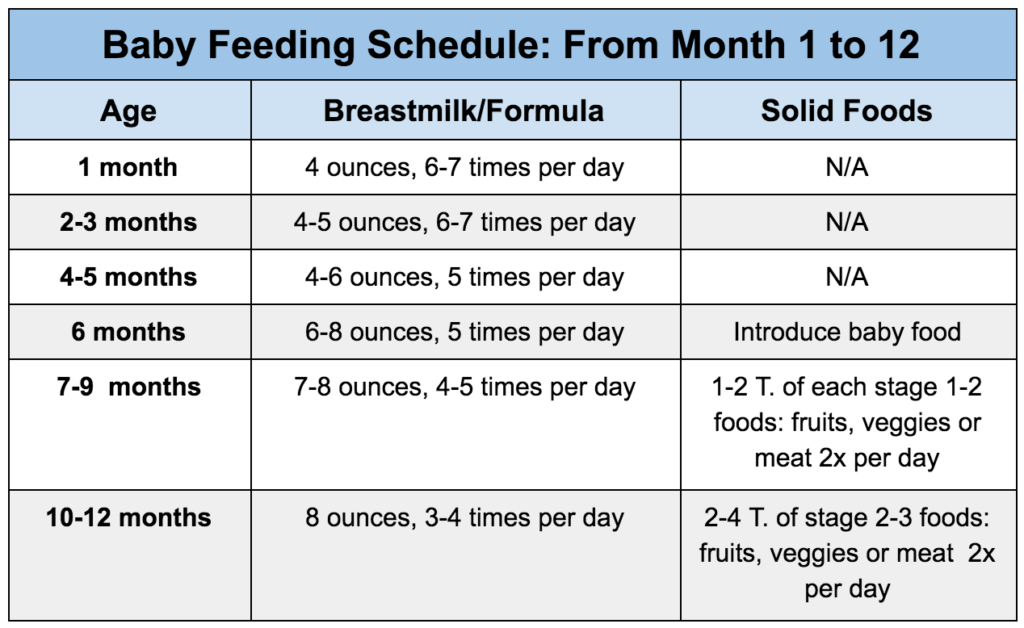

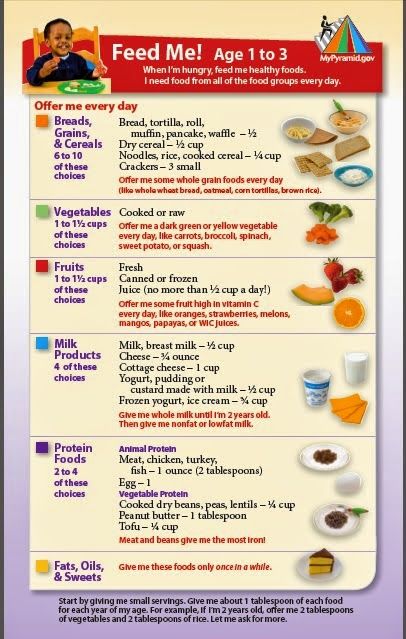

What about solid foods? When and how should you introduce your baby to solids? This Parenting Science article will guide you through the process, and answer interesting questions about infant behavior, adding spices to foods, and more.

And are some other Parenting Science articles that might interest you:

- Baby sleep patterns for the science-minded

- The newborn senses: What can babies feel, see, hear, smell, and taste

- Stress in babies: How to keep babies calm, happy, and healthy

- Motor milestones: How do babies develop during the first two years?

References: The best infant feeding schedule

Agostoni C, Marangoni F, Grandi F, Lammardo AM, Giovannini M, Riva E, Galli C. 2003. Earlier smoking habits are associated with higher serum lipids and lower milk fat and polyunsaturated fatty acid content in the first 6 months of lactation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 57(11):1466-72.

Al-Tamer YY and Mahmood AA.2006. The influence of Iraqi mothers’ socioeconomic status on their milk-lipid content. Eur J Clin Nutr. 60(12):1400-5.

American Academy of Pediatrics. 2015. Caring for your baby and young child: Birth to age 5. 7th Edition. T. Altmann (ed). Bantam.

Argov-Argaman N, Mandel D, Lubetzky R, Hausman Kedem M, Cohen BC, Berkovitz Z, Reifen R. 2017. Human milk fatty acids composition is affected by maternal age. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 30(1):34-37.

2017. Human milk fatty acids composition is affected by maternal age. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 30(1):34-37.

Barr RG, Pantel MS, Young SN, Wright JH, Hendricks LA, Gravel R. 1999. The response of crying newborns to sucrose: is it a “sweetness” effect? Physiol. Behav 66: 409-417.

Bergmeier HJ, Skouteris H, Haycraft E, Haines J, Hooley M. 2015. Reported and observed controlling feeding practices predict child eating behavior after 12 months. J Nutr. 145(6):1311-6.

Blass EM. 1997a Milk-induced hypoanalgesia in human newborns. Pediatrics 99: 825-829.

Blass EM. 1997b. Infant formula quiets crying newborns. Journal of Dev Behavioral Pediatrics. 18:162-165.

Brown A and Lee M. 2012. Breastfeeding during the first year promotes satiety responsiveness in children aged 18-24 months. Pediatr Obes. 7(5):382-90.

Chen TL, Chen YY, Lin CL, Peng FS, Chien LY. 2020. Responsive Feeding, Infant Growth, and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms During 3 Months Postpartum. Nutrients. 12(6):1766.

12(6):1766.

Daly SE, DiRosso A, Owens RA and Hartmann PE. 1993. Degree of breast emptying explains fat content, but not fatty acid composition, of human milk. Exp Physiol 78: 741-755.

Daniel AI, Shama S, Ismail S, Bourdon C, Kiss A, Mwangome M, Bandsma RHJ, O’Connor DL. 2021. Maternal BMI is positively associated with human milk fat: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 113(4):1009-1022.

Dinkevich E, Leid L, Pryor K, Wei Y, Huberman H, Carnell S. 2015. Mothers’ feeding behaviors in infancy: Do they predict child weight trajectories? Obesity (Silver Spring). 23(12):2470-6.

Disantis KI, Collins BN, Fisher JO, and Davey A. 2011a. Do infants fed directly from the breast have improved appetite regulation and slower growth during early childhood compared with infants fed from a bottle? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 8:89.

Disantis KI, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, and Fisher JO. 2011b. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: a systematic review. International Journal of Obesity 35: 480–492

International Journal of Obesity 35: 480–492

Fomon SJ, Filmer, Jr., JA, Thomas LN, Anderson TA and Nelson SE. 1975. Influence of formula concentration on caloric intake and growth of normal infants. Acta Pediatrica Scandinavica 64: 172-181.

Fuglestad AJ, Demerath EW, Finsaas MC, Moore CJ, Georgieff MK, Carlson SM. 2017. Maternal executive function, infant feeding responsiveness and infant growth during the first 3 months. Pediatr Obes. 12 Suppl 1:102-110.

Gubbels JS, Thijs C, Stafleu A, van Buuren S, Kremers SP. 2011. Association of breast-feeding and feeding on demand with child weight status up to 4 years. Int J Pediatr Obes. 6(2-2):e515-22.

Gray L, Miller LW, Philipp BL, Blass EM. 2002. Breastfeeding is analgesic in healthy newborns. Pediatrics 109: 590-593.

Gray L, Watt L, Blass EM. Skin-to-skin contact is analgesic in healthy newborns. Pediatrics 105(1).

Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Fierman AH, Hauser NR, Messito MJ. 2014. Maternal infant feeding behaviors and disparities in early child obesity. Child Obes. 10(2):145-52.

Child Obes. 10(2):145-52.

Hausman Kedem M, Mandel D, Domani KA, Mimouni FB, Shay V, Marom R, Dollberg S, Herman L, Lubetzky R. 2013. The effect of advanced maternal age upon human milk fat content. Breastfeed Med. 8(1):116-9.

Hester SN, Hustead DS, Mackey AD, Singhal A, and Marriage BJ. 2012. Is the macronutrient intake of formula-fed infants greater than breast-fed infants in early infancy? Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism: 891201.

Iacovou M and Sevilla A. 2013. Infant feeding: the effects of scheduled vs. on-demand feeding on mothers’ wellbeing and children’s cognitive development. Eur J Public Health. 23(1):13-9.

Illingworth RS, Stone DHG, Jowett JH and Scott JF. 1952. Self-demand feeding in a maternity unit. Lancet 1: 683-687.

Innis SM. 2014. Impact of maternal diet on human milk composition and neurological development of infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 99(3):734S-41S.

Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. 1991. Nutrition during lactation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jackson DA, Imong SM, Silpraset A, Preunglumpoo Ruckphaopunt S, Williams AF, Woolridge MW, Baum JD, and Amatayakul K. 1988. Circadian variation in fat concentration of breastmilk in rural Northern Thailand. British Journal of Nutrition 59: 365-371.

Jani R, Mallan KM, Daniels L.2015. Association between Australian-Indian mothers’ controlling feeding practices and children’s appetite traits. Appetite 84:188-95

Jenness 1974. Biosynthesis and composition of milk. Journal of investigative dermatology. 63: 109-118.

Kersting M and Dulon M. 2001. Assessment of breastfeeding promotion in hospitals and follow up survey of mother-infant pairs in Germany: The Su-Se study. Public Health Nutrition 5(4): 547-552.

Khan S, Hepworth AR, Prime DK, Lai CT, Trengove NJ, Hartmann PE. 2013. Variation in fat, lactose, and protein composition in breast milk over 24 hours: associations with infant feeding patterns. J Hum Lact. 29(1):81-9

Konner M. 2005. Hunter-gatherer infancy and childhood: The !Kung and others. In: Hunter-gatherer childhoods: Evolutionary, developmental and cultural perpectives. BS Hewlett and ME Lamb (eds). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

2005. Hunter-gatherer infancy and childhood: The !Kung and others. In: Hunter-gatherer childhoods: Evolutionary, developmental and cultural perpectives. BS Hewlett and ME Lamb (eds). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Li R, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. 2010. Do infants fed from bottles lack self-regulation of milk intake compared with directly breastfed infants? Pediatrics. 125(6):e1386-93.

Mandel D, Lubetzky R, Dollberg S, Barak S, Mimouni FB. 2005. Fat and energy contents of expressed human breast milk in prolonged lactation. Pediatrics. 116(3):e432-5.

Mihrshahi S, Battistutta D, Magarey A, Daniels LA. 2011. Determinants of rapid weight gain during infancy: baseline results from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 11:99.

Prentice AM and Prentice A. 1988. Energy costs of lactation. Annual review of nutrition 8: 63-79.

Prentice A, Prentice AM and Whitehead RG. 1981. Breast-milk concentrations of rural African women I. Short-term variations within individuals. British Journal of Nutrition 45: 483-494.

British Journal of Nutrition 45: 483-494.

Rocquelin G, Tapsoba S, Dop MC, Mbemba F, Traissac P, Martin-Prével Y. 1998. Lipid content and essential fatty acid (EFA) composition of mature Congolese breast milk are influenced by mothers’ nutritional status: impact on infants’ EFA supply. Eur J Clin Nutr. 52(3):164-71

Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Massey R, Campbell KJ, Wertheim EH, Skouteris H, Gibbons K. 2013. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: a prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 10:24

Saxon TF, Gollapalli A, Mitchell MW, and Stanko S. 2002. Demand feeding or schedule feeding: infant growth from birth to 6 months. Journal of reproductive and infant psychology 20(2): 89-99.

Severn Nelson EA, Schiefenhoevel W, and Haimerl F. 2000. Child care practices in nonindustrial societies. Pediatrics 105: 75-79.

Shah PS, Aliwalas L, and Shah V. 2007. Breastfeeding or breast milk to alleviate procedural pain in neonates: a systematic review. Breastfeeding medicine 2:74-82.

Breastfeeding medicine 2:74-82.

Spill MK, Callahan EH, Shapiro MJ, Spahn JM, Wong YP, Benjamin-Neelon SE, Birch L, Black MM, Cook JT, Faith MS, Mennella JA, Casavale KO. 2019. Caregiver feeding practices and child weight outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 109(Suppl_7):990S-1002S.

Szabó E, Boehm G, Beermann C, Weyermann M, Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Decsi T. 2010. Fatty acid profile comparisons in human milk sampled from the same mothers at the sixth week and the sixth month of lactation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 50(3):316-20.

Tilden CD and Oftedal OT. 1997. Milk composition reflects pattern of maternal care in prosimian primates. American Journal of Primatology 41: 195-211.

Tylka TL, Lumeng JC, Eneli IU. 2015. Maternal intuitive eating as a moderator of the association between concern about child weight and restrictive child feeding. Appetite 95:158-65.

Ventura AK, Inamdar LB, Mennella JA. 2015. Consistency in infants’ behavioural signalling of satiation during bottle-feeding. Pediatr Obes. 10(3):180-7.

Pediatr Obes. 10(3):180-7.

Wojcik KY, Rechtman DJ, Lee ML, Montoya A, Medo ET. 2009. Macronutrient analysis of a nationwide sample of donor breast milk. J Am Diet Assoc. 109(1):137-40.

Woolridge MW. 1995. Baby-controlled breastfeeding: Biocultural implications. In: Breastfeeding: Biocultural perspectives. P. Stuart-Macadam and KA Dettwyler (eds). New York: Aldine deGruyter.

Woolridge MW and Baum JD. 1992. Infant appetite-control and the regulation of breast milk supply. Children’s hospital quarterly 3:133-119.

Woolridge MW and Fisher C. 1988. Colic, ‘Overfeeding,’ and Symptoms of Lactose Malabsorption in the Breast-Fed Baby: A Possible Artifact of Feed Management. Lancet 13: 382-384.

Note: Portions of this article, “Jettisoning the infant feeding schedule: Why babies are better off feeding on cue,” are taken from an earlier Parenting Science article, “The infant feeding schedule: Why babies benefit from feeding on demand.” The material here has been updated and substantially revised.

For more references pertaining to the infant feeding schedule, see my article on breastfeeding on demand.

Image credits for “The best infant feeding schedule”

image of infant breastfeeding by istock / Jomkwan

Content of “The best infant feeding schedule” last modified 5/2021

Breastfeeding: on Demand or Schedule

JanelMS, RD, LDN, CBS

Read time: 5 minutes

What to know about breastfeeding on-demand versus on a schedule

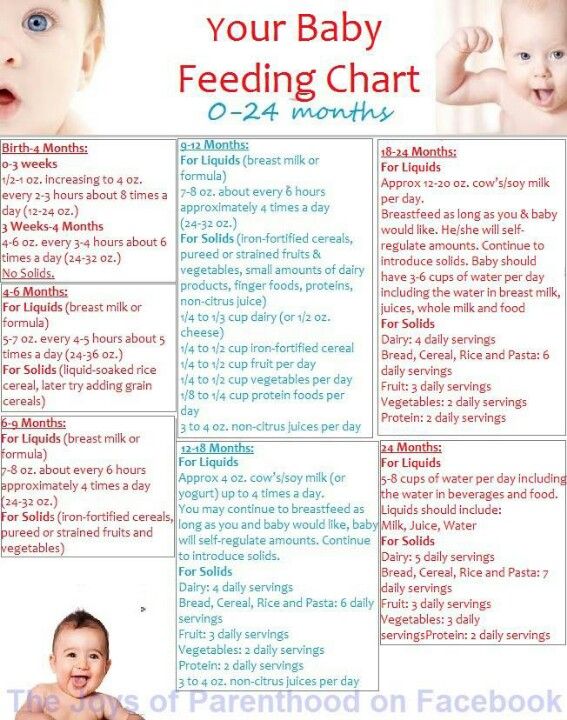

Feeding needs vary depending on baby’s age

Know when to expect a natural feeding pattern to emerge

Understand your baby’s and your body’s signs that it’s time to feed

Many new parents wonder if they should be breastfeeding on demand or on a schedule. On demand breastfeeding, also called cue-based, baby-led, or responsive breastfeeding, is when you follow your baby’s cues for when and how much to feed. On the other hand, feeding on a schedule means you’re breastfeeding at specific times, and perhaps for a specific amount of time, that is not determined by the baby. 10

10

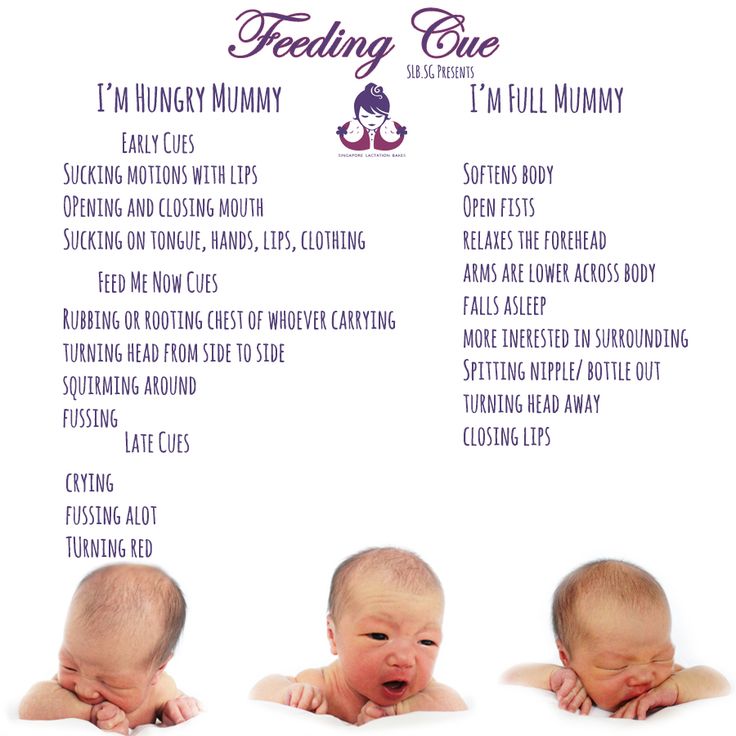

Early on in your baby’s life, feeding on demand is best.1 Breastfeeding is instinctual for babies. They show hunger when their body needs nutrients and calories for growth and development. As soon as you see those feeding cues, let them drink up! In fact, breastfeeding on demand helps support a healthy breastmilk supply as well.2

Read on to learn about when it’s best to breastfeed on demand, and when you may finally start to see a feeding schedule begin to emerge.

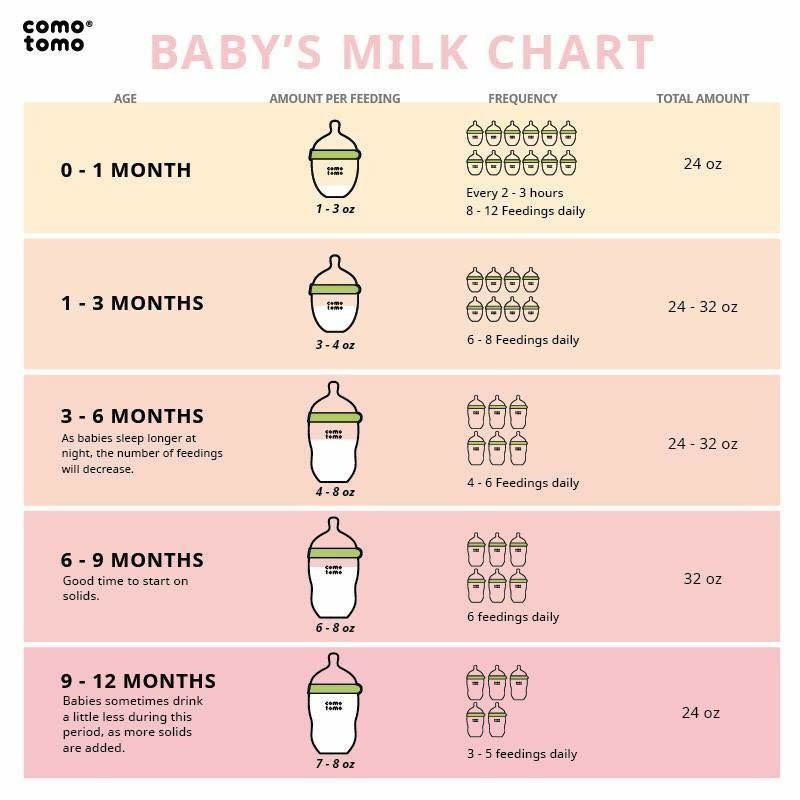

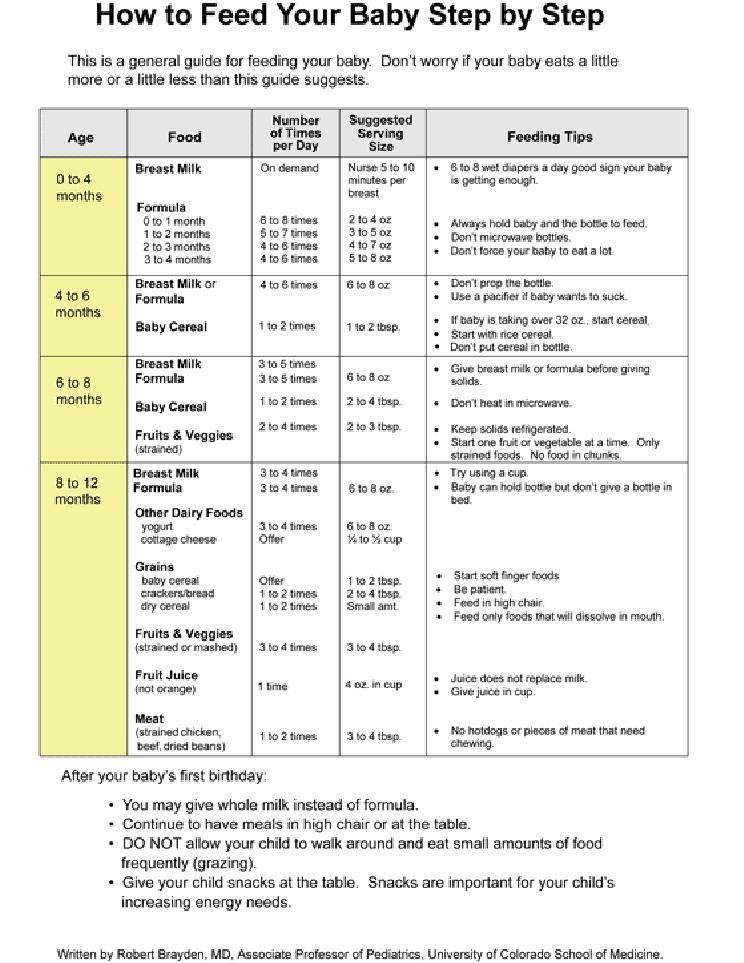

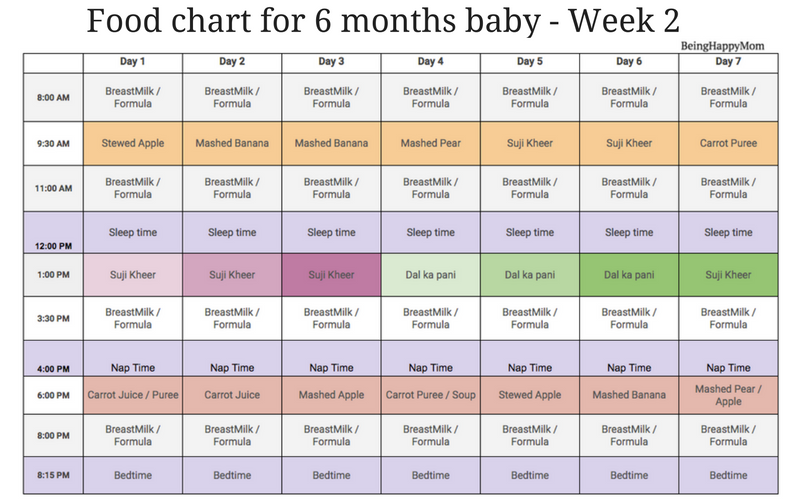

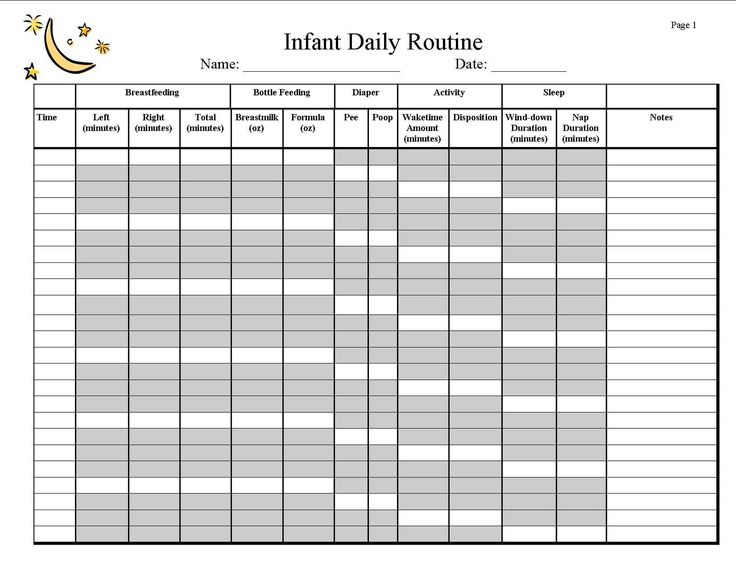

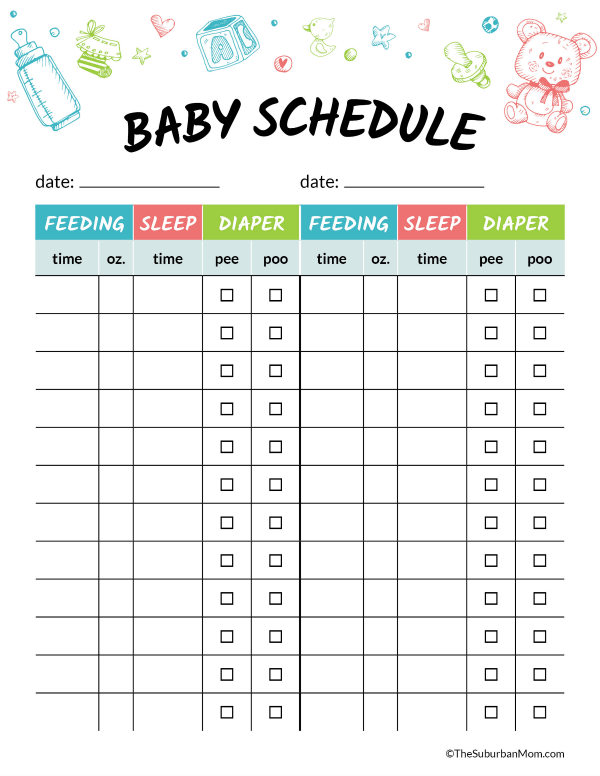

How often does my newborn need to breastfeed?Breastmilk is easily digestible, and newborn’s stomachs are tiny, resulting in your baby needing to eat around the clock. Breastfed infants usually eat 8 to 12 times per 24 hours, or about every 1 to 3 hours.3,4 Each feed may last anywhere from 15 minutes to 20 minutes per breast, give or take depending on each infant. 5

5

Frequent on-demand feedings benefit both you and your baby. Breastmilk production works by supply and demand, the more you feed, the more milk the body will make.6 Following your baby’s lead and feeding as frequently as they demand will help your body know exactly how much milk it needs to make to meet your baby’s needs. Scheduled feeds may interrupt this natural process of milk production.

Read more: Breastfeeding: How to Support a Good Milk Supply

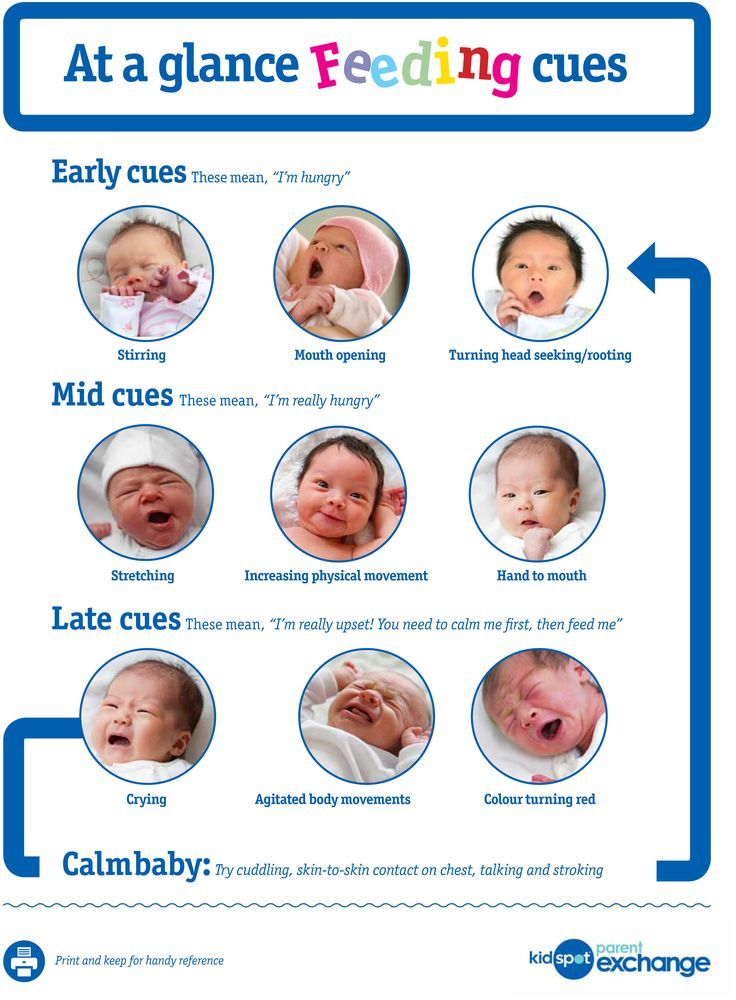

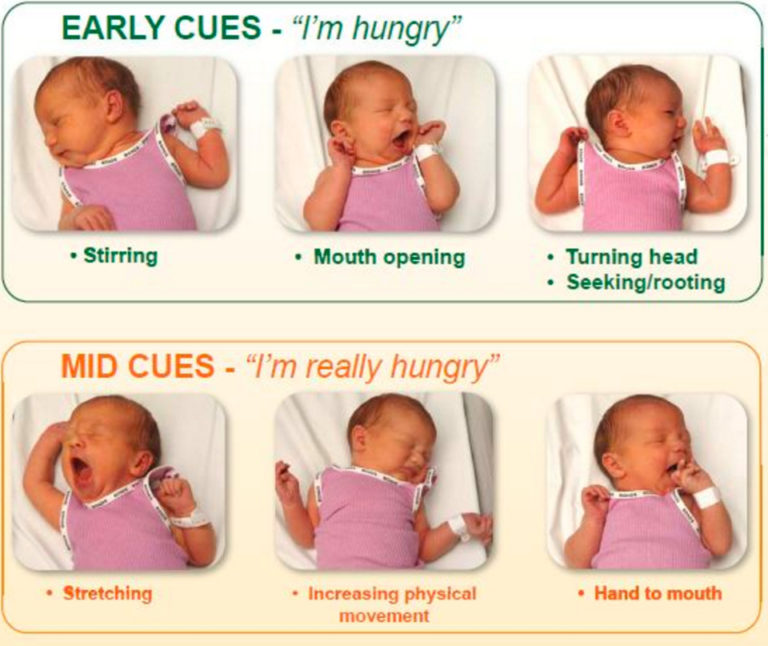

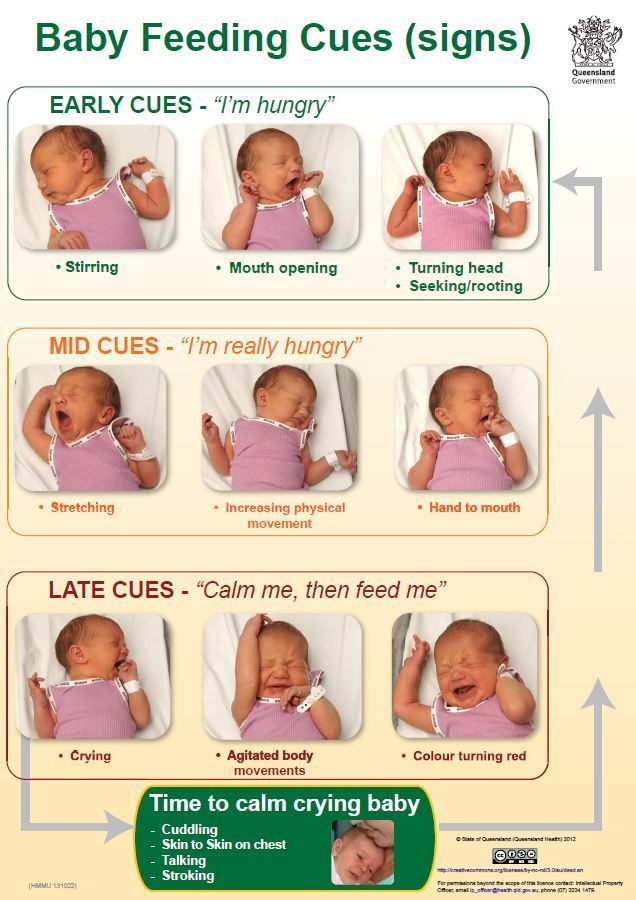

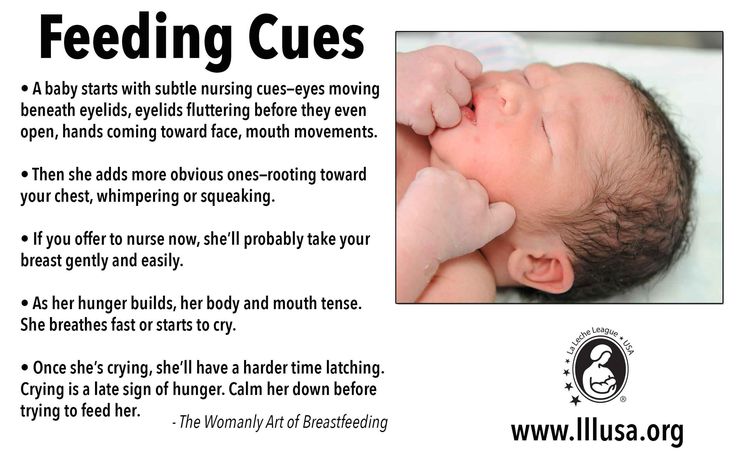

How do I know when my breastfed baby is hungry?Signs that your baby is hungry and ready to breastfeed include:

Becoming more alert

Putting their hands or fingers on or in their mouth

Making sucking motions or sounds

Sticking their tongue out or smacking lips

Rooting (moving their jaw and mouth or head in search of the breast).7

Many caregivers think crying is the main sign of hunger, however crying is actually a late-stage hunger cue and a sign of distress. Watch for earlier hunger cues, as once a baby is crying, it can be harder to get them to latch onto the breast and feed.7,8

Watch for earlier hunger cues, as once a baby is crying, it can be harder to get them to latch onto the breast and feed.7,8

Read more: Understanding Your Baby’s Hunger and Fullness Cues

How much breastmilk can your breasts hold? Does breast size affect breastmilk production?The good news is that total volume of milk you’re able to make per day is not related to the size of your breast.2 The size of your breast is solely related to the amount of fatty tissue. However, the capacity of your milk-making glandular tissue to hold breastmilk is strictly related to how much milk you can store at one time.2

People with a smaller breastmilk storage capacity may need to feed their babies more often for their little one to get enough.2,9 With this smaller capacity, your breasts may feel full often, and it may be best to feed baby (or express milk) when you feel the sensation to release milk. This helps to keep the milk flowing, which can help prevent problems such as leaking, engorgement, low supply, plugged ducts, and mastitis.9,12

This helps to keep the milk flowing, which can help prevent problems such as leaking, engorgement, low supply, plugged ducts, and mastitis.9,12

Learn about: Avoiding and Managing Blocked Ducts while Breastfeeding

Responsive feeding for healthy growth in breastfed babiesIn the first year of life your baby has very high calorie needs in proportion to their small body size. The average baby will triple their birth weight in the first year.12,13 All of this growth is dependent on good feeding practices. Meeting your baby’s needs by feeding on demand in response to their cues ensures adequate growth, nutrient intake, and helps promote the essential bonding moments that happen between baby and caregiver.

It can be tempting to encourage your baby to stay at the breast and feed more, or feed more often than they are asking; however, unless your doctor has instructed you to do so, it’s better to allow your baby to guide the feeding. Let them decide how slow, how often, and how much they eat.1 This is called responsive feeding, and it’s the practice of following and responding to your baby’s hunger and fullness cues.

Let them decide how slow, how often, and how much they eat.1 This is called responsive feeding, and it’s the practice of following and responding to your baby’s hunger and fullness cues.

You will learn about how often and for how long your baby typically breastfeeds. Over time, your baby will fall into their own breastfeeding schedule, which will then continually change over time. And don’t be surprised if the amount your baby drinks varies throughout the day. Just like adults, babies don’t need all their feeds to be the same size.4

When does a breastfeeding schedule emerge?At around 3 to 4 months old, you may notice a more predictable feeding pattern emerge. For example, your baby may begin to space out feedings from every 2 to 3 hours to every 3 to 4 hours. This type of pattern is helpful in creating a natural breastfeeding rhythm and routine, but don’t assume that this is the way feeding will go from now on. Babies are constantly growing, and their needs will change frequently to support that growth.

Babies are constantly growing, and their needs will change frequently to support that growth.

The schedule may still shift from day to day and will continue to change as your baby grows. A baby is a little person after all; some days they’re hungrier than others, so continue to watch for your baby’s hunger cues and make adjustments accordingly.

Wondering if your baby’s feeding pattern is normal and meeting their needs? Reach out to our team of registered dietitians and lactation consultants for free! They’re here to help on our free to live chat from Monday – Friday 8am - 6pm (ET), and Saturday – Sunday 8am - 2pm (ET). Chat Now!

Breastfeeding on-demand and cluster feedingBabies have multiple growth spurts during their first 6 months. During these times your little one needs more calories and nutrients to meet their growth and development needs, so for a couple days they’ll seem like all they want to do is feed, feed, feed all day long. This is called ‘cluster feeding’. Some babies even act fussier at the breast during these times.15

Some babies even act fussier at the breast during these times.15

The good news is that feeding this frequently helps your body make more breastmilk to meet baby’s growing needs.14

When can you expect growth spurts and cluster feeding?

2 – 3 weeks

4 - 6 weeks

3 months

6 months14

Cluster feeding can also happen for some babies every day at a certain time of day. For example, some little ones cluster feed every evening before bed for the first 4 to 6 weeks of life.15 By following your baby’s lead and feeding on demand, you will help meet their needs as well as support your breastmilk supply.

Read about: Dealing with Low Breastmilk Supply

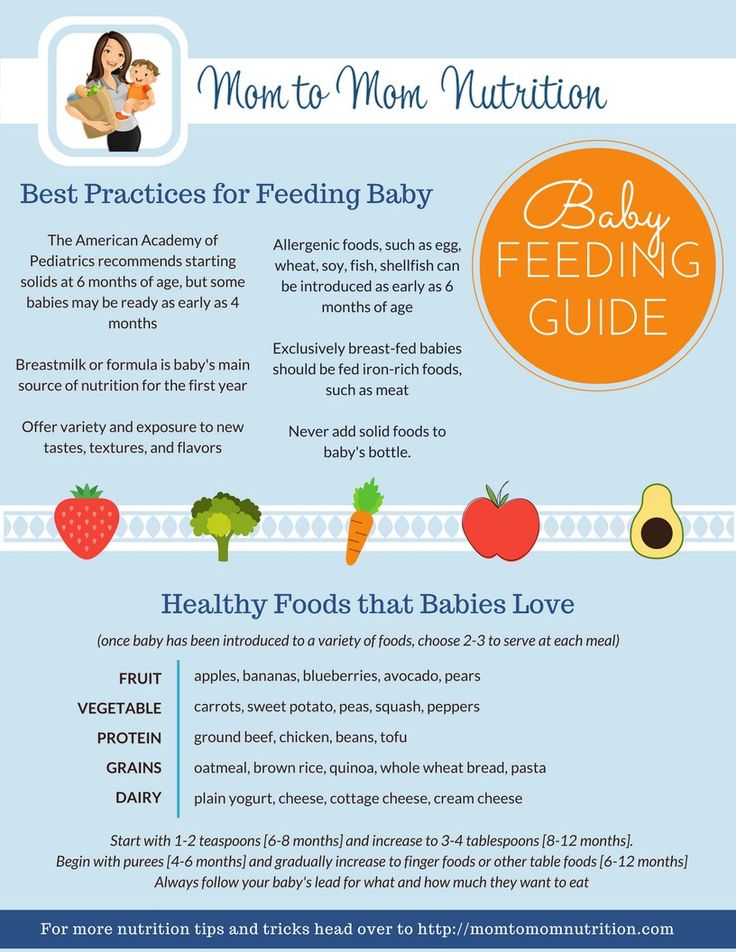

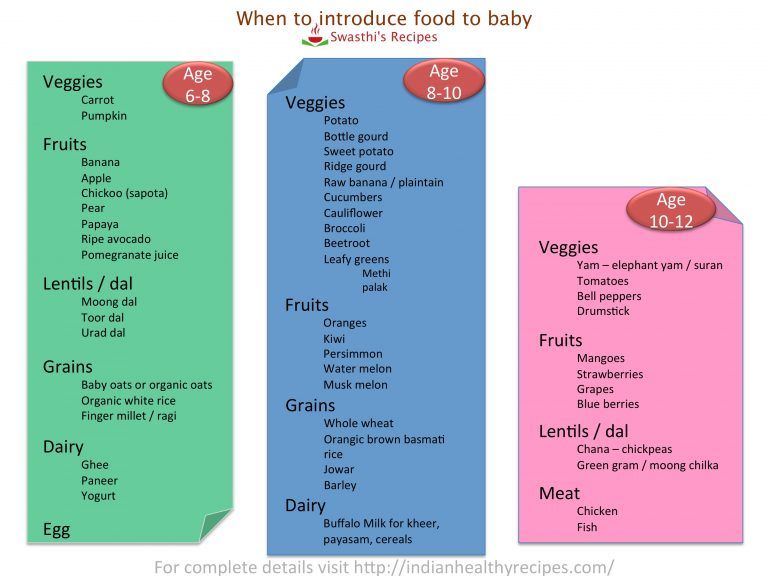

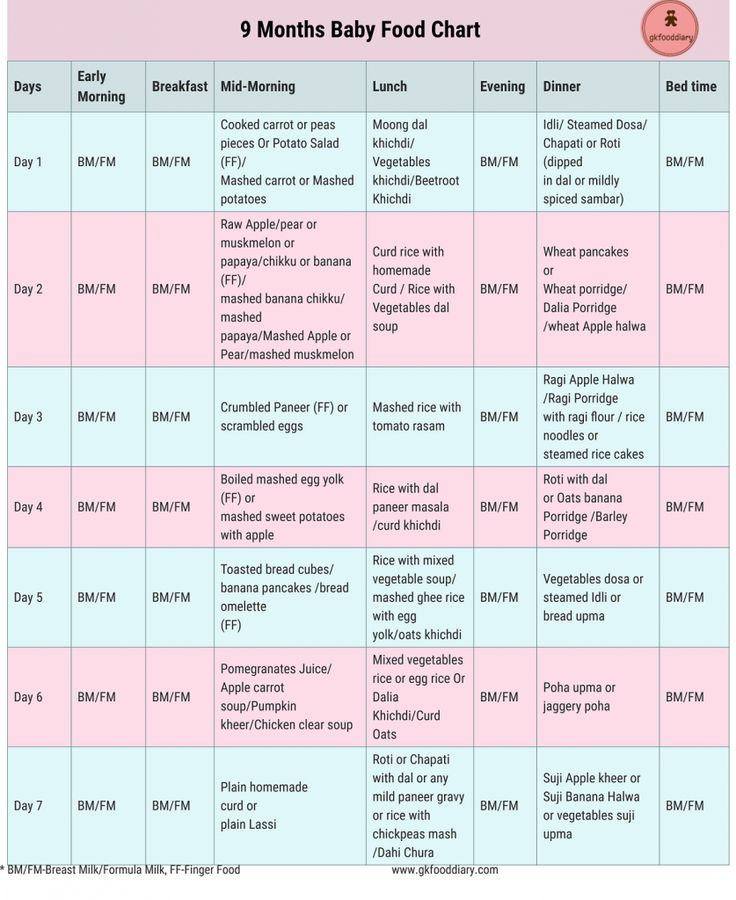

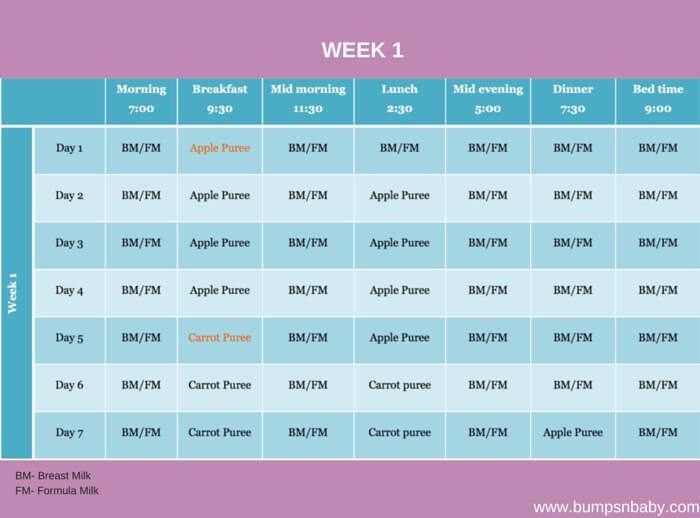

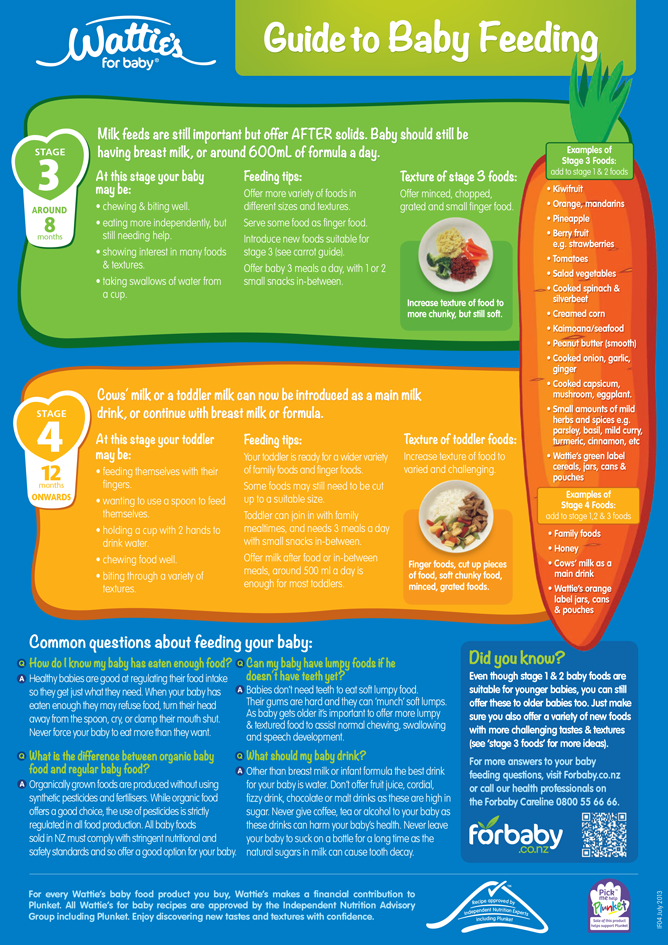

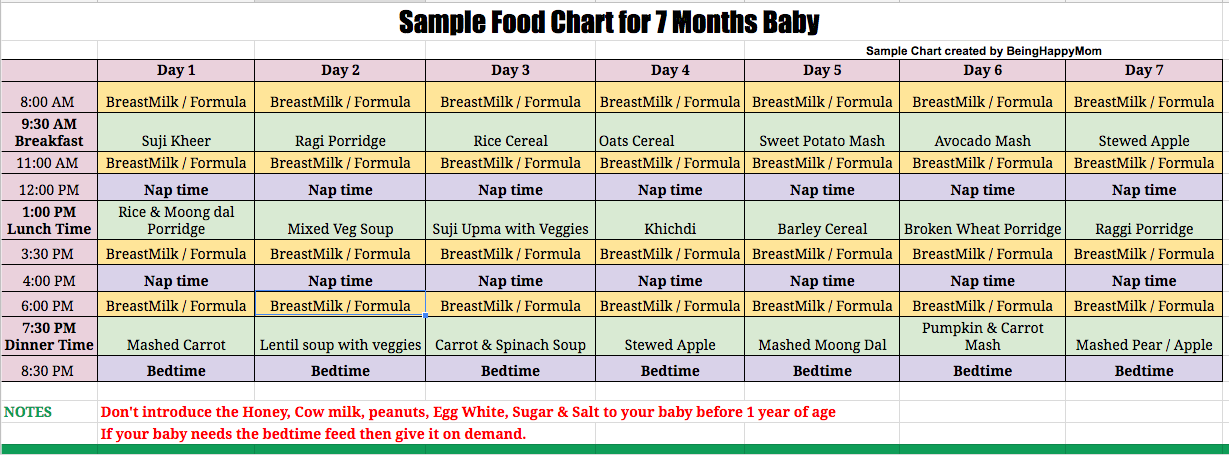

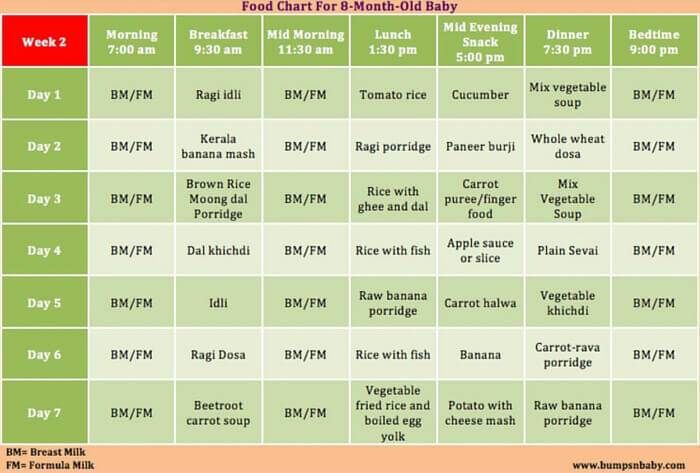

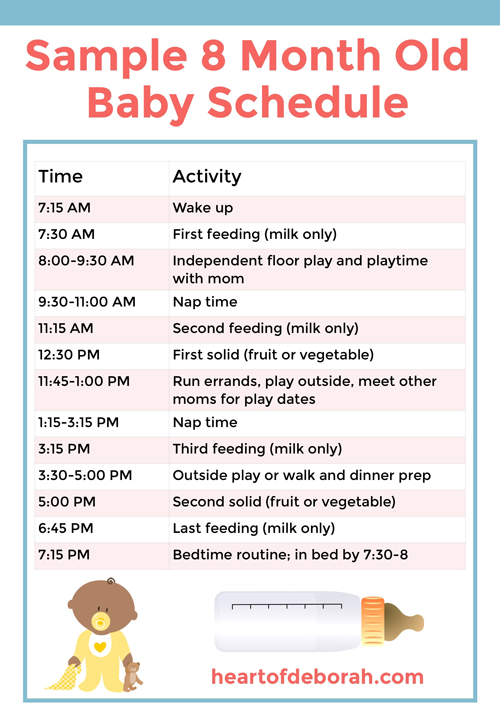

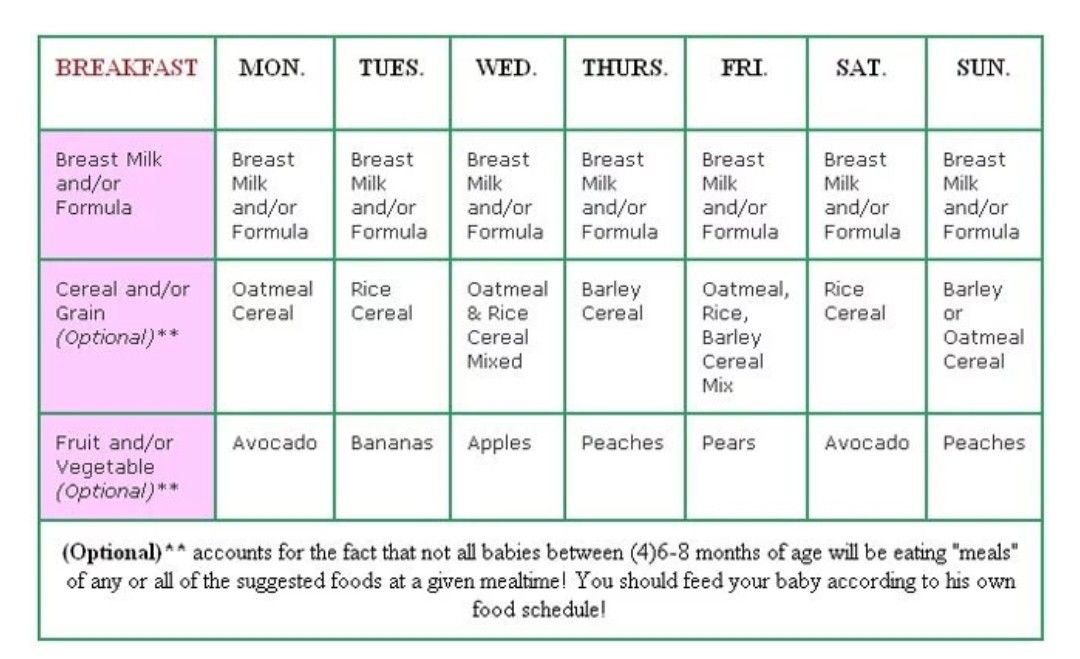

Starting solids and baby’s breastfeeding scheduleAt around 6 months old, when babies typically begin solids, a more consistent feeding schedule often develops. Sometimes these schedules mimic parents eating schedules or daycare schedules but just as often they don’t, so be prepared to meet baby’s schedule rather than have him meet yours.

Sometimes these schedules mimic parents eating schedules or daycare schedules but just as often they don’t, so be prepared to meet baby’s schedule rather than have him meet yours.

By 6 months most babies’ feeding schedules consist of a breastfeeding at least 6 to 8 times per 24 hours (sometimes more!) as well as solid food feeding 1 to 2 times per day.4

If your baby seems less interested in breastfeeding once solids are introduced, be sure to provide breastmilk before offering solids.4 Breastmilk should remain the primary source of calories and nutrients for babies under the age of 1 year.16

Read more:

Meal Plan for 6 to 9 Month Old Baby

Introducing Solids: First Foods and Textures

Why might breastfeeding on a schedule not work?If you were to schedule breastfeeding sessions rather than listen to your baby and your body, there is a higher likelihood of your breastmilk supply reducing. This is especially true if a schedule is implemented during the first few months of life when your breastmilk supply is so highly reliant upon your body learning how much milk to make from how much milk your baby asks for.2,9

This is especially true if a schedule is implemented during the first few months of life when your breastmilk supply is so highly reliant upon your body learning how much milk to make from how much milk your baby asks for.2,9

For some women, scheduled feedings may lead to some unpleasant side effects, such as increased risk of clogged ducts, painful engorgement, and ultimately low supply.2,11

What should I do to support my breastfed baby’s feeding schedule?Know that the newborn feeding pattern is usually the toughest and most unpredictableIf you’re in the thick of the first 8 weeks, take a deep breath! You and baby are both still learning, and things will get easier for both of you with time. Focus on baby’s feeding cues and know most newborns will breastfeed 8 to 12 times per 24 hours.

Remember that your baby will likely start to space out their feedings in a more predictable pattern after 3 to 4 months.

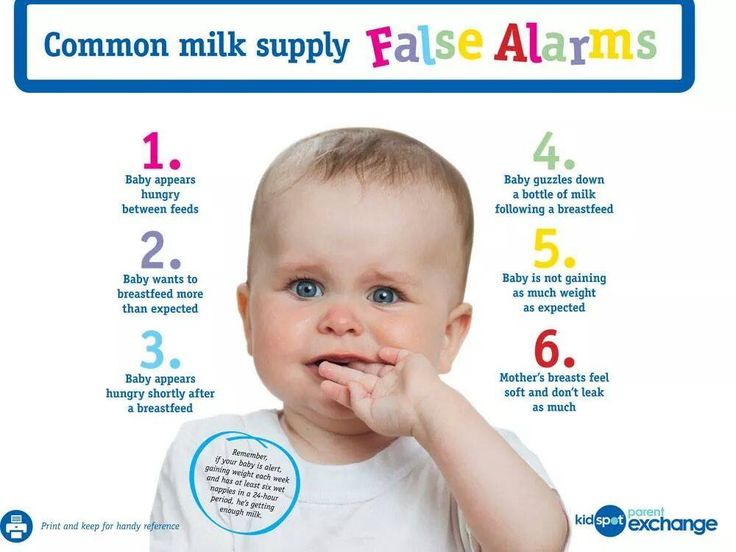

Know if your baby is getting enough breastmilkHaving your little one demand to eat often can sometimes make us doubt our breastmilk supply. The good news is that usually there is no problem with how much we are producing!

Here is how you’ll know your baby is getting enough breastmilk:

Baby is making 5+ wet diapers per 24 hours

Baby is making 3 to 4 (or more) dirty diapers per 24 hours

Baby seems satisfied and happy between feedings

Baby is gaining weight well18,19

Using breast compressions while baby is feeding can help push more milk out to help your little one stay interested in the feed and help them get enough. This is particularly helpful if your little one is not an efficient feeder quite yet or if they are falling asleep at the breast too soon.17

This is particularly helpful if your little one is not an efficient feeder quite yet or if they are falling asleep at the breast too soon.17

Place your hand around the breast with your thumb on one side (the top side is usually easiest) and your fingers on the other side. Your hand should be close to your chest wall, leaving plenty of space around your areola.17 Gently squeeze your breast and hold.

This technique may be helpful but is not guaranteed, and it’s important not to do this aggressively! The compressions should not be painful.

Read more: How and When to Hand Express

Build a strong support networkBreastfeeding is a demanding job and may come with some challenges. Reach out to friends and family members who have breastfed and find a local breastfeeding support group.

If you’re facing significant breastfeeding challenges, you may want to seek out an in-person lactation consultant (IBCLC) for help.

We know parenting often means sleepless nights, stressful days, and countless questions and confusion, and we want to support you in your feeding journey and beyond.

Our Happy Baby Experts are a team of lactation consultants and registered dietitians certified in infant and maternal nutrition – and they’re all moms, too, which means they’ve been there and seen that. They’re here to help on our free, live chat platform Monday - Friday 8am - 6pm (ET), and Saturday - Sunday 8am - 2pm (ET).Chat Now!

Read more about the experts that help write our content!

For more on this topic, check out the following articles:Dealing With a Low Breastmilk SupplyBreastfeeding: How to Support a Good Milk Supply

Meal and Hydration Plan for Supporting Milk Supply

How to Choose the Right Breast Pump

6 Breastfeeding Positions for You and Your Baby

Top Tips for Pumping Breastmilk

Sources

Breastfeeding in the first month: what to expect

Not sure how to establish lactation and increase milk production? If you need help, support, or just want to know what to expect, read our first month breastfeeding advice

Share this information

The first weeks of breastfeeding are a very stressful period. If at times you feel like you can't handle it, know that you are not alone. Feeding your baby all day long is completely natural and helps produce breast milk, but can be quite tiring at times. Be patient, think about yourself and remember: after the first month, when milk production stabilizes, it will become easier. nine0003

If at times you feel like you can't handle it, know that you are not alone. Feeding your baby all day long is completely natural and helps produce breast milk, but can be quite tiring at times. Be patient, think about yourself and remember: after the first month, when milk production stabilizes, it will become easier. nine0003

How often should a baby be breastfed?

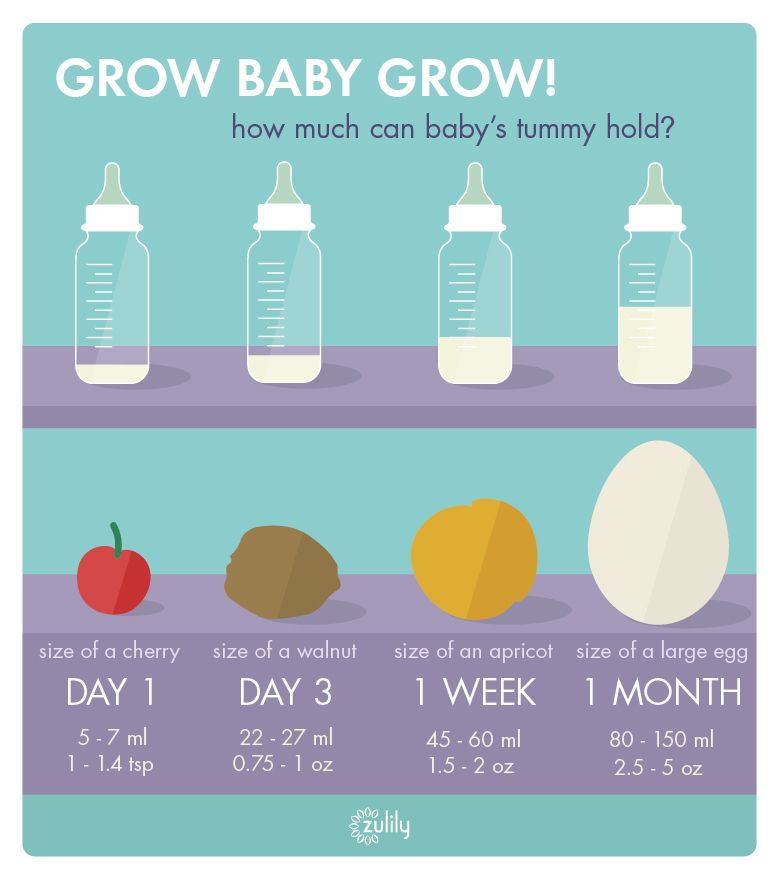

Babies are born with a small stomach that grows rapidly with increasing milk production: in the first week it is no larger than an apricot, and after two weeks it is already the size of a large chicken egg. 1.2 Let the child eat as much as he wants and when he wants. This will help him quickly regain the weight lost after birth and grow and develop further.

“Be prepared to feed every two to three hours throughout the day. At night, the intervals between feedings can be longer: three to four or even five hours, says Cathy Garbin, a recognized international expert on breastfeeding. Some eat quickly and are satiated in 15 minutes, while others take an entire hour to feed. Do not compare your breastfeeding regimen with that of other mothers - it is very likely that there will be nothing in common between them. nine0003

Do not compare your breastfeeding regimen with that of other mothers - it is very likely that there will be nothing in common between them. nine0003

At each feed, give your baby a full meal from one breast and then offer a second one, but don't worry if the baby doesn't take it. When the baby is full, he lets go of his chest and at the same time looks relaxed and satisfied - so much so that he can immediately fall asleep. The next time you feed, start on the other breast. You can monitor the order of the mammary glands during feeding using a special application.

Why does the child always ask for a breast?

The first month is usually the hardest time to breastfeed. But do not think that because the baby is constantly hungry and asks for a breast almost every 45 minutes, then you do not have enough milk. nine0003

In the first month, the baby needs to eat frequently to start and stimulate the mother's milk production. It lays the foundation for a stable milk supply in the future. 3

3

In addition, we must not forget that the child needs almost constant contact with the mother. The bright light and noise of the surrounding world at first frighten the baby, and only by clinging to his mother, he can calm down.

Sarah, mother of three from the UK, confirms: “Crying is not always a sign of hunger. Sometimes my kids just wanted me to be around and begged for breasts to calm them down. Use a sling. Place the cradle next to the bed. Don't look at the clock. Take advantage of every opportunity to relax. Forget about cleaning. Let those around you take care of you. And not three days, but six weeks at least! Hug your baby, enjoy the comfort - and trust your body." nine0003

Do I need to feed my baby on a schedule?

Your baby is still too young for a strict daily routine, so

forget about breastfeeding schedules and focus on his needs.

“Volumes have been written about how to feed a baby on a schedule, but babies don't read or understand books,” Cathy says. - All children are different. Some people can eat on a schedule, but most can't. Most often, over time, the child develops his own schedule.

- All children are different. Some people can eat on a schedule, but most can't. Most often, over time, the child develops his own schedule.

Some mothers report that their babies are fine with scheduled feedings, but they are probably just the few babies who would eat every four hours anyway. Adults rarely eat and drink the same foods at the same time of day - so why do we expect this from toddlers?

Offer your baby the breast at the first sign of hunger. Crying is already the last stage, so be attentive to early signs: the baby licks his lips, opens his mouth, sucks his fist, turns his head with his mouth open - looking for the breast. nine0013 4

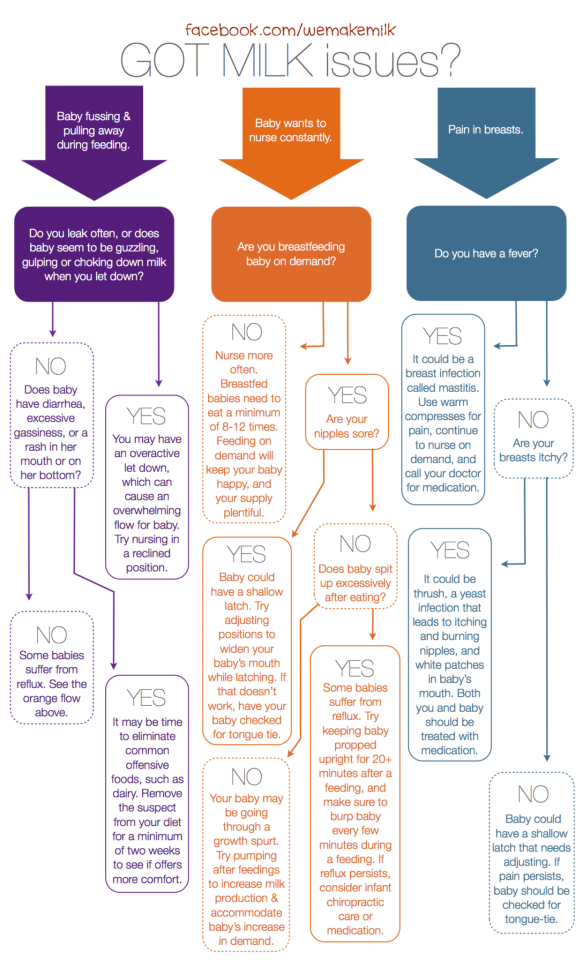

What is a "milk flush"?

At the beginning of each feed, a hungry baby actively sucks on the nipple,

thereby stimulating the milk flow reflex - the movement of milk through the milk ducts. 5

“Nipple stimulation triggers the release of the hormone oxytocin,” explains Cathy. “Oxytocin is distributed throughout the body and causes the muscles around the milk-producing glands to contract and the milk ducts to dilate. This stimulates the flow of milk. nine0003

This stimulates the flow of milk. nine0003

If the flushing reflex fails, milk will not come out. This is a hormonal response, and under stress it may not work at all or work poorly. Therefore, it is so important that you feel comfortable and calm when feeding.

“Studies show that each mother has a different rhythm of hot flashes during one feed,” Kathy continues, “Oxytocin is a short-acting hormone, it breaks down in just 30-40 seconds after formation. Milk begins to flow, the baby eats, the effect of oxytocin ends, but then a new rush of milk occurs, the baby continues to suckle the breast, and this process is repeated cyclically. That is why, during feeding, the child periodically stops and rests - this is how nature intended. nine0003

The flow of milk may be accompanied by a strong sensation of movement or tingling in the chest, although 21% of mothers, according to surveys, do not feel anything at all. 5 Cathy explains: “Many women only feel the first rush of milk. If you do not feel hot flashes, do not worry: since the child eats normally, most likely, you simply do not understand that they are.

If you do not feel hot flashes, do not worry: since the child eats normally, most likely, you simply do not understand that they are.

How do you know if a baby is getting enough milk?

Since it is impossible to track how much milk a baby eats while breastfeeding, mothers sometimes worry that the baby is malnourished. Trust your child and your body. nine0003

After a rush of milk, the baby usually begins to suckle more slowly. Some mothers clearly hear how the baby swallows, others do not notice it. But one way or another, the child himself will show when he is full - just watch carefully. Many babies make two or three approaches to the breast at one feeding. 6

“When a child has had enough, it is noticeable almost immediately: a kind of “milk intoxication” sets in. The baby is relaxed and makes it clear with his whole body that he is completely full, says Katie, “Diapers are another great way to assess whether the baby is getting enough milk. During this period, a breastfed baby should have at least five wet diapers a day and at least two portions of soft yellow stool, and often more. ” nine0003

” nine0003

From one month until weaning at six months of age, a baby's stool (if exclusively breastfed) should look the same every day: yellow, grainy, loose, and watery.

When is the child's birth weight restored?

Most newborns lose weight in the first few days of life. This is normal and should not be cause for concern. As a rule, weight is reduced by 5-7%, although some may lose up to 10%. One way or another, by 10–14 days, almost all newborns regain their birth weight. In the first three to four months, the minimum expected weight gain is an average of 150 grams per week. But one week the child may gain weight faster, and the next slower, so it is necessary that the attending physician monitor the health and growth of the baby constantly. nine0013 7.8

At the slightest doubt or signs of dehydration, such as

dark urine, no stool for more than 24 hours, retraction of the fontanel (soft spot on the head), yellowing of the skin, drowsiness, lethargy, lack of appetite (ability to four to six hours without feeding), you should immediately consult a doctor. 7

7

What is "cluster feeding"?

When a baby asks to breastfeed very often for several hours, this is called cluster feeding. nine0013 6 The peak often occurs in the evening between 18:00 and 22:00, just when many babies are especially restless and need close contact with their mother. Most often, mothers complain about this in the period from two to nine weeks after childbirth. This is perfectly normal and common behavior as long as the baby is otherwise healthy, eating well, gaining weight normally, and appears content throughout the day. 9

Cluster feeding can be caused by a sharp jump in the development of the body - during this period the baby especially needs love, comfort and a sense of security. The growing brain of a child is so excited that it can be difficult for him to turn off, or it just scares the baby. nine0013 9 If a child is overworked, it is often difficult for him or her to calm down on his own, and adult help is needed. And breastfeeding is the best way to calm the baby, because breast milk is not only food, but also pain reliever and a source of happiness hormones. 10

And breastfeeding is the best way to calm the baby, because breast milk is not only food, but also pain reliever and a source of happiness hormones. 10

“Nobody told me about cluster feeding, so for the first 10 days I just went crazy with worry - I was sure that my milk was not enough for the baby,” recalls Camille, a mother from Australia, “It was a very difficult period . I was advised to pump and supplement until I finally contacted the Australian Breastfeeding Association. There they explained to me what was happening: it turned out that it was not about milk at all. nine0003

Remember, this is temporary. Try to prepare dinner for yourself in the afternoon, when the baby is fast asleep, so that in the evening, when he begins to often breastfeed, you have the opportunity to quickly warm up the food and have a snack. If you are not alone, arrange to carry and rock the baby in turns so that you have the opportunity to rest. If you have no one to turn to for help and you feel that your strength is leaving you, put the baby in the crib and rest for a few minutes, and then pick it up again. nine0003

nine0003

Ask your partner, family and friends to help you with household chores, cooking and caring for older children if you have any. If possible, hire an au pair. Get as much rest as possible, eat well and drink plenty of water.

“My daughter slept a lot during the day, but from 23:00 to 5:00 the cluster feeding period began, which was very tiring,” recalls Jenal, a mother from the USA, “My husband tried his best to make life easier for me - washed, cleaned, cooked, changed diapers, let me sleep at every opportunity and never tired of assuring me that we were doing well. nine0003

If you are concerned about the frequency of breastfeeding, it is worth contacting a specialist. “Check with a lactation consultant or doctor to see if this is indicative of any problems,” recommends Cathy. “Resist the temptation to supplement your baby with formula (unless recommended by your doctor) until you find the cause. It may not be a matter of limited milk production at all - it may be that the child is inefficiently sucking it.

When will breastfeeding become easier? nine0011

This early stage is very special and does not last long. Although sometimes it seems that there will be no end to it, rest assured: it will get easier soon! By the end of the first month, breast milk production will stabilize, and the baby will become stronger and learn to suckle better. 2.3 Any problems with latch on by this time will most likely be resolved and the body will be able to produce milk more efficiently so inflammation and leakage of milk will begin to subside.

“The first four to six weeks are the hardest, but then things start to get better,” Cathy assures. It just needs to be experienced!” nine0003

The longer breastfeeding continues, the more benefits it brings, from saving on formula and improving sleep quality 11–13 to boosting your baby's immune system 14 and reducing your risk of certain cancers. 15

“When you feel like you're pushing yourself, try to go from feed to feed and day to day,” says Hannah, a UK mom. “I was sure I wouldn’t make it to eight weeks. And now I have been breastfeeding for almost 17 weeks, and I dare say it is very easy.” nine0003

“I was sure I wouldn’t make it to eight weeks. And now I have been breastfeeding for almost 17 weeks, and I dare say it is very easy.” nine0003

Read the resource Breastfeeding Beyond the First Month: What to Expect

Literature

1 Naveed M et al. An autopsy study of relationship between perinatal stomach capacity and birth weight. Indian J Gastroenterol .1992;11(4):156-158. - Navid M. et al., Association between prenatal gastric volume and birth weight. Autopsy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1992;11(4):156-158.

2 Neville MC et al. Studies in human lactation: milk volumes in lactating women during the onset of lactation and full lactation .Am J Clinl Nutr . 1988;48(6):1375-1386. at the beginning and at the peak of lactation." Am F Clean Nutr. 1988;48(6):1375-1386.

3 Kent JC et al. Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet , Gynecol , & Neonatal Nurs . 2012;41(1):114-121. - Kent J.S. et al., "Principles for Maintaining and Increasing Milk Production". J Obstet Ginecol Neoneutal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114-121. nine0129

Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet , Gynecol , & Neonatal Nurs . 2012;41(1):114-121. - Kent J.S. et al., "Principles for Maintaining and Increasing Milk Production". J Obstet Ginecol Neoneutal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114-121. nine0129

4 Australian Breastfeeding Feeding cues ; 2017 Sep [ cited 2018 Feb ]. - Australian Breastfeeding Association [Internet], Feed Ready Signals; September 2017 [cited February 2018]

5 Kent JC et al. Response of breasts to different stimulation patterns of an electric breast pump. J Human Lact . 2003;19(2):179-186. - Kent J.S. et al., Breast Response to Different Types of Electric Breast Pump Stimulation. J Human Lact (Journal of the International Association of Lactation Consultants). 2003;19(2):179-186.

J Human Lact (Journal of the International Association of Lactation Consultants). 2003;19(2):179-186.

6) Kent JC et al . Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3): e 387-395. - Kent J.S. et al., "Amount and frequency of breastfeeding and fat content of breast milk during the day." Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2006;117(3):e387-95.

7 Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical profession. 7th ed. Maryland Heights MO, USA: Elsevier Mosby; 2010. 1128 p . - Lawrence R.A., Lawrence R.M., "Breastfeeding: A guide for healthcare professionals." Seventh edition. Publisher Maryland Heights , Missouri, USA: Elsevier Mosby; 2010. P. 1128.

8 World Health Organization. [Internet]. Child growth standards; 2018 [cited 2018 Feb] - World Health Organization. [Internet]. Child Growth Standards 2018 [cited February 2018]. nine0129

[Internet]. Child growth standards; 2018 [cited 2018 Feb] - World Health Organization. [Internet]. Child Growth Standards 2018 [cited February 2018]. nine0129

9 Australian Breastfeeding Association . [ Internet ]. Cluster feeding and fussing babies ; Dec 2017 [ cited 2018 Feb ] - Australian Breastfeeding Association [Internet], Cluster Feeding and Screaming Babies; December 2017 [cited February 2018]. nine0129

10 Moberg KU, Prime DK. Oxytocin effects in mothers and infants during breastfeeding. Infant . 2013;9(6):201-206.- Moberg K, Prime DK, "Oxytocin effects on mother and child during breastfeeding". Infant. 2013;9(6):201-206.

11 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [Internet]. Surgeon General Breastfeeding factsheet; 2011 Jan 20 [cited 2017 Feb] - Department of Health and Human Services [Internet], "Breastfeeding Facts from the Chief Medical Officer", Jan 20, 2011 [cited Feb 2017]

12 Kendall-Tackett K et al. The effect of feeding method on sleep duration, maternal well-being, and postpartum depression. clinical lactation. 2011;1;2(2):22-26. - Kendall-Tuckett, K. et al., "Influence of feeding pattern on sleep duration, maternal well-being and the development of postpartum depression." Clinical Lactation. 2011;2(2):22-26.

The effect of feeding method on sleep duration, maternal well-being, and postpartum depression. clinical lactation. 2011;1;2(2):22-26. - Kendall-Tuckett, K. et al., "Influence of feeding pattern on sleep duration, maternal well-being and the development of postpartum depression." Clinical Lactation. 2011;2(2):22-26.

13 Brown A, Harries V. Infant sleep and night feeding patterns during later infancy: Association with breastfeeding frequency, daytime complementary food intake, and infant weight. Breast Med . 2015;10(5):246-252. - Brown A., Harris W., "Night feedings and infant sleep in the first year of life and their association with feeding frequency, daytime supplementation, and infant weight." Brest Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2015;10(5):246-252.

14 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clin Transl immunology. 2013;2(4). - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." nine0129 Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

Clin Transl immunology. 2013;2(4). - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." nine0129 Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

15 Li DP et al. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev . 2014;15(12):4829-4837. - Lee D.P. et al., "Breastfeeding and the risk of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies." Asia Pas J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4829-4837.

Breastfeeding a newborn | What to Expect in the First Week

The first week of a baby's life is a wonderful but hectic time, especially if you haven't breastfed before. Our breastfeeding tips will help you settle in as quickly as possible

Share this information

The first time after childbirth, mothers are often confused. The body is still recovering, and you are already starting to get to know your newborn baby. The emotional state during this period can be unstable, especially between the second and fifth day, when many women have milk 1 and at the same time postpartum depression begins 2 . In addition, people around often expect (and demand) that a woman come to her senses as soon as possible and become a “super mom”. But the best thing to do this first week is just to be with your baby and get breastfeeding going.

The body is still recovering, and you are already starting to get to know your newborn baby. The emotional state during this period can be unstable, especially between the second and fifth day, when many women have milk 1 and at the same time postpartum depression begins 2 . In addition, people around often expect (and demand) that a woman come to her senses as soon as possible and become a “super mom”. But the best thing to do this first week is just to be with your baby and get breastfeeding going.

When should I start breastfeeding my newborn?

Try to breastfeed your baby within the first hour after birth. When the baby latch onto the breast and begins sucking rhythmically, it stimulates the mammary gland cells and starts milk production. nine0013 1 It is not for nothing that this time is called the “magic hour”!

“Ideally, the baby should be placed on the mother's stomach immediately after birth so that it can immediately attach to the breast. He won't necessarily eat, but he should be able to,” explains Cathy Garbin, an internationally recognized expert on breastfeeding.

He won't necessarily eat, but he should be able to,” explains Cathy Garbin, an internationally recognized expert on breastfeeding.

“Hold your baby and let him find the breast on his own and put the nipple in his mouth. This is called the breast-seeking reflex. On the Internet you can watch videos that show what this process looks like. If the baby does not latch onto the nipple on its own, the midwife will help to properly attach it to the breast. But for starters, it’s good to give the baby the opportunity to do it on their own. In this case, the optimal position for the mother is reclining. ” nine0003

Don't spend that special first hour of your baby's life weighing and swaddling—or at least wait until he's suckling for the first time. Enjoy hugs and close skin-to-skin contact. This promotes the production of oxytocin, the hormone of love, in you and your baby, and oxytocin plays a key role in the supply of the first breast milk - colostrum. 3

“As soon as the obstetricians were convinced that our son was healthy, the three of us — me, my husband and our baby — were left to give us the opportunity to get to know each other. It was a very special hour - an hour of awkwardness, turbulent emotions and bliss. During this time, I breastfed my son twice, ”recalls Ellie, a mother of two from the UK. nine0003

It was a very special hour - an hour of awkwardness, turbulent emotions and bliss. During this time, I breastfed my son twice, ”recalls Ellie, a mother of two from the UK. nine0003

Did you know that breastfeeding helps to recover after childbirth? This is because oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions. In the first hours after childbirth, this contributes to the natural release of the placenta and reduces blood loss. 4

What if the birth did not go according to plan?

If you had a caesarean section or other complications during childbirth,

You can still establish skin-to-skin contact with your baby and breastfeed him in the first hours after birth. nine0003

“If you can't hold your baby, have your partner do it for you and make skin-to-skin contact with the baby. This will give the baby a sense of security, care and warmth so that he can hold on until you recover, ”Katie advises.

If the baby is unable to breastfeed, it is advisable to start expressing milk as early as possible and do so as often as possible until the baby is able to feed on its own. “While breastfeeding in the first hours after birth lays an excellent foundation for the future, it is not so important,” Cathy reassures. “It is much more important to start lactation so that in the future, if necessary, you can start breastfeeding.” nine0003

“While breastfeeding in the first hours after birth lays an excellent foundation for the future, it is not so important,” Cathy reassures. “It is much more important to start lactation so that in the future, if necessary, you can start breastfeeding.” nine0003

To start milk production, you can express milk manually or use a breast pump that can be given to you at the hospital. 5 And with expressed precious colostrum, it will be possible to feed the child. This is especially important if the baby was born premature or weak, since breast milk is extremely healthy.

If a baby was born prematurely or has a medical condition and cannot be breastfed immediately, this is no reason not to continue breastfeeding. “I have worked with many new mothers who were unable to breastfeed their baby for the first six weeks due to preterm labor or other reasons. Nevertheless, all of them later successfully switched to breastfeeding,” says Kathy. nine0003

Does the baby latch on correctly?

Correct breastfeeding is essential for successful breastfeeding 6 , as it determines how effectively the baby will suckle milk and hence grow and develop. Latching on the breast incorrectly can cause sore or damaged nipples, so don't hesitate to ask your doctor to check that your baby is properly attached to the breast, even if you are told that everything is fine and you do not see obvious problems - especially while you are in the hospital. nine0003

Latching on the breast incorrectly can cause sore or damaged nipples, so don't hesitate to ask your doctor to check that your baby is properly attached to the breast, even if you are told that everything is fine and you do not see obvious problems - especially while you are in the hospital. nine0003

“While I was in the hospital, I called the doctor at every feed and asked me to check if I was breastfeeding correctly,” says Emma, mother of two from Australia. - There were several cases when it seemed to me that everything seemed to be right, but it was painful to feed, and the doctor helped me take the baby off the breast and attach it correctly. By the time I was discharged, I had already learned to do it confidently.”

When applying to the breast, point the nipple towards the palate. This will allow the baby to take the nipple and part of the areola under it into their mouth. It will be easier for him to suck if he has both the nipple and part of the areola around in his mouth. nine0013 6

nine0013 6

“When a baby latch on properly, it doesn't cause discomfort and it causes a pulling sensation, not pain,” Cathy explains. - The baby's mouth is wide open, the lower lip may be slightly turned outward, and the upper one lies comfortably on the chest. The body language of the child indicates that he is comfortable. There isn't much milk at this early stage, so you probably won't notice your baby swallowing, but he will suckle a lot and nurse frequently."

How often should a newborn be fed? nine0011

The frequency and duration of breastfeeding in the first week can vary greatly. “The first 24 hours of life are completely different for different children. Someone sleeps a lot (after all, childbirth is tiring!), And someone often eats, says Katie. - Such a variety greatly confuses young mothers. Everyone gives different advice, so it's important to remember that every mother and child is different."

“Colostrum is thicker than mature breast milk and is produced in smaller amounts, but has many benefits. When the baby eats colostrum, he learns to suck, swallow and breathe until milk begins to flow in more volume, ”explains Cathy. nine0003

When the baby eats colostrum, he learns to suck, swallow and breathe until milk begins to flow in more volume, ”explains Cathy. nine0003

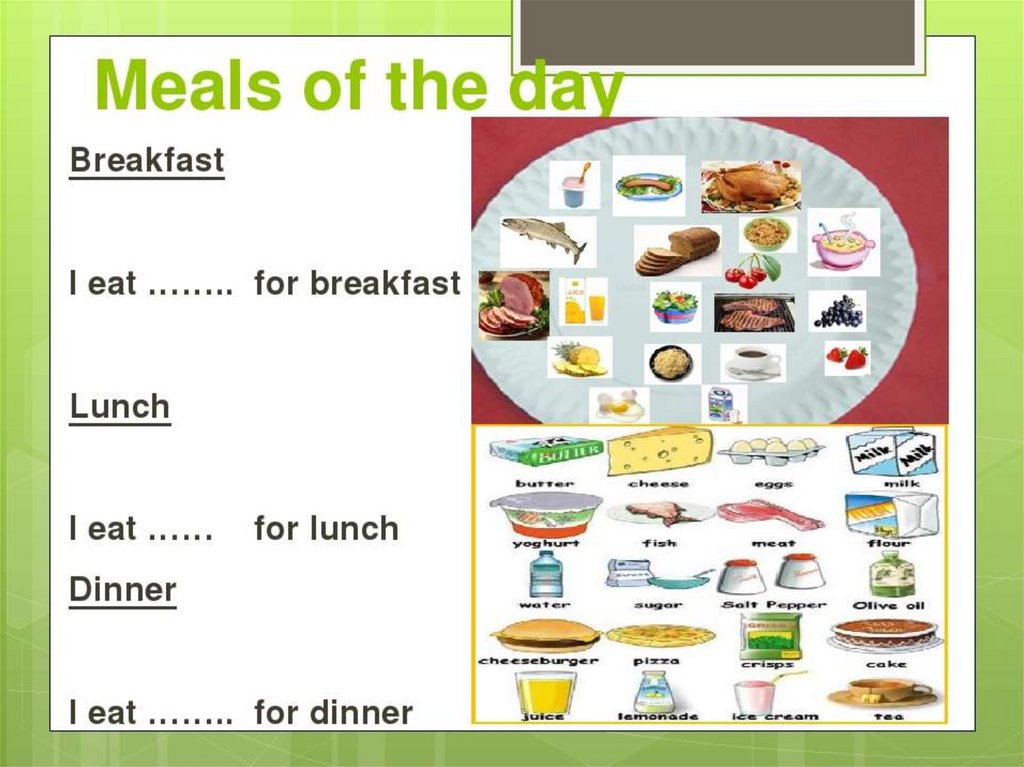

Milk usually arrives on the second or fourth day after birth. Until this time, the baby is applied to the breast 8-12 times a day (and sometimes more often!), including at night. 7 Feeding may take 10-15 minutes at this stage, or 45 minutes or even an hour, as the baby is just beginning to develop the muscles and coordination needed to suckle effectively.

“At first, the intensity of feeding is very high, often higher than many people realize, and this is shocking to most new mothers,” says Cathy. - Sometimes mom has no time to go to the toilet, take a shower and have a snack. It usually comes as a surprise." nine0003

Camille, a mother from Australia, experienced this. “The first week, Frankie ate every two hours, day and night, and each time it took half an hour to an hour to feed,” she recalls. “My husband and I were completely exhausted!”

Do I need to feed my newborn on a schedule?

The good news is that frequent feeding promotes lactation and stimulates milk production. 7 The more your baby eats, the more milk you will have. Therefore, forget about feeding your newborn on a schedule - this way he will have less chance of feeding. Try to feed your baby when he signals that he is hungry 8 :

7 The more your baby eats, the more milk you will have. Therefore, forget about feeding your newborn on a schedule - this way he will have less chance of feeding. Try to feed your baby when he signals that he is hungry 8 :

- toss and turn in her sleep;

- opens eyes;

- turns his head if he feels a touch on his cheek;

- sticks out tongue;

- groans;

- licks lips;

- sucks fingers;

- is naughty;

- whimpers;

- is crying.

Crying is the last sign of hunger, so if in doubt, just offer your baby the breast. If he bursts into tears, it will be more difficult to feed him, especially at first, when both of you are just learning how to do it. As your baby grows, he will likely eat less frequently and take less time to feed, so breastfeeding will seem more predictable. nine0003

Does breastfeeding hurt?

You may have heard that breastfeeding is not painful at all, but in fact, in the early days, many new mothers experience discomfort. And this is not at all surprising, given that the nipples are not used to such frequent and strong sucking.

And this is not at all surprising, given that the nipples are not used to such frequent and strong sucking.

“Breastfeeding can be uncomfortable for the first couple of days – your body and your baby are just getting used to it. If a baby eats for too long and does not latch well, the sensations are almost the same as from unworn new shoes, Cathy compares. Just as tight shoes can rub your feet, improper suckling can damage your nipples. Prevention is always better than cure, so if the pain persists after a few days of feeding, contact a lactation consultant or healthcare professional.” nine0003

Maria, a mother from Canada, agrees: “Although my son seemed to latch onto the breast well, he damaged his nipples while feeding, and I was in pain. As it turned out, the reason was a shortened frenulum of the tongue. The breastfeeding specialists at our city clinic have been of great help in diagnosis and treatment.”

In addition, you may experience period cramps during the first few days after breastfeeding, especially if this is not your first baby. This is the so-called postpartum pain. The fact is that oxytocin, which is released during breastfeeding, contributes to further contraction of the uterus to restore its normal size. nine0013 4

This is the so-called postpartum pain. The fact is that oxytocin, which is released during breastfeeding, contributes to further contraction of the uterus to restore its normal size. nine0013 4

When milk arrives, the breasts usually become fuller, firmer and larger than before delivery. In some women, the breasts swell, harden and become very sensitive - swelling of the mammary glands occurs. 10 Frequent breastfeeding relieves these symptoms. For more breast care tips, read our article What is Breast Swelling?

How often does a newborn urinate and defecate?

What goes into the body must go back out. Colostrum

has a laxative effect, helping to eliminate meconium - the original feces. It looks a little scary - black and sticky, like tar. 11 But don't worry, it won't always be like this. Breastfed babies usually have a slightly sweet smell of stool.

How many times a day you will need to change diapers and how the contents should look like, see below.

Day one

- Frequency: once or more.

- Colour: greenish black. nine0506

- Texture: sticky like tar.

Day two

- Frequency: twice or more.

- Colour: dark greenish brown.

- Texture: less sticky.

Day three

- Frequency: twice or more.

- Colour: greenish brown to brownish yellow.

- Texture: non-sticky.

Fourth day and then the entire first month

- Frequency: twice or more.

- Color: yellow (feces should turn yellow no later than the end of the fourth day).

- Texture: grainy (like mustard with grains interspersed). Leaky and watery.

The baby's urine should be light yellow. On average, babies urinate once a day for the first two days. Starting around the third day, the number of wet diapers increases to three, and from the fifth day onwards, diapers have to be changed five times a day or more often. In addition, during the first few days, the weight of wet diapers increases. nine0013 11

In addition, during the first few days, the weight of wet diapers increases. nine0013 11

Is the baby getting enough breast milk?

Since very little milk is produced at first,

You may feel that your baby is not getting enough milk. But if you feed your baby on demand, you will produce exactly as much milk as he needs. If you want to keep the process under control, be guided by the frequency of diaper changes above. If your baby soils less diapers, check with your doctor.

“For the first three or four weeks, most babies just eat and sleep. If the child is worried and constantly asks for a breast, you should consult with your doctor, ”Katie recommends. nine0003

Sometimes the baby may vomit after feeding. If the vomit is the color of milk, this is not a cause for concern. But if there are orange, red, green, brown or black blotches in it, or the child vomits with a "fountain", consult a doctor. You should also consult a doctor if the baby has a high temperature, the fontanel (soft spot on the head) has sunk, blood is found in the stool, and also if the weight recorded at birth has not recovered within two weeks. 11

11

But if there are no frightening symptoms and the baby is growing at a normal pace, then he has enough milk. Soon you will both get used to breastfeeding and establish a more stable routine.

For the next step in breastfeeding, see Breastfeeding in the First Month: What to Expect.

Literature

1 Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J9 Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia . 2007;12(4):211-221. - Pang, W.W., Hartmann, P.I., "Lactation initiation in the lactating mother: secretory differentiation and secretory activation." G Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12(4):211-221.

2 Shashi R et al. Postpartum psychiatric disorders: Early diagnosis and management. Indian J Psychiatry . 2015; 57( Suppl 2): S 216– S 221. - Shashi R. et al., Postnatal mental disorders: early diagnosis and treatment. Indian J Saikiatri. 2015; 57(App 2):S216-S221.