Foods that cause eczema in breastfed babies

Breastfeeding and maternal diet in atopic dermatitis

Can Fam Physician. 2011 Dec; 57(12): 1403–1405.

Language: English | French

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Question Many children are affected by atopic dermatitis (AD) at a very young age. I often consider whether nonpharmacologic interventions could prevent or mitigate the development of AD. Do breastfeeding or changes to the maternal diet help prevent the development of childhood AD?

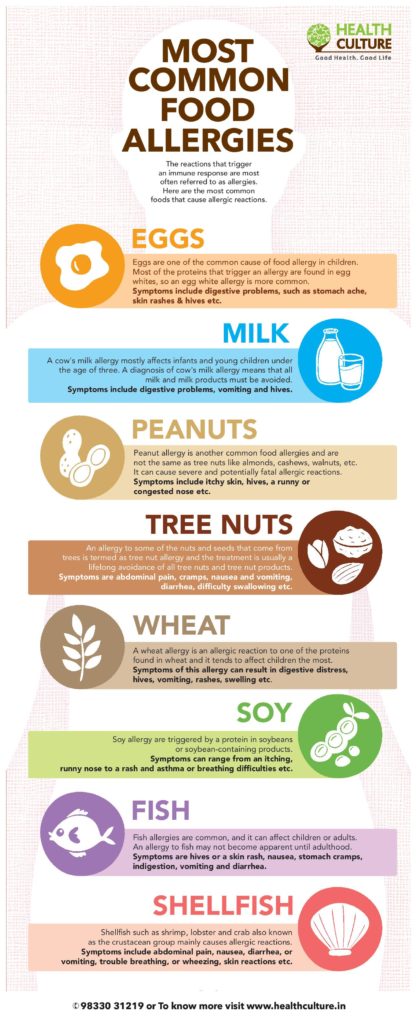

Answer The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that lactating mothers with infants at high risk of developing AD should avoid peanuts and tree nuts, and should consider eliminating eggs, cow’s milk, and fish from their diets. The World Health Organization also recommends breastfeeding infants up to 2 years of age. Studies have shown that breastfeeding can have a protective effect for AD in children; however, other studies have found insignificant or reversal effects. More research in this area is required.

Question De nombreux enfants sont affectés par la dermatite atopique (DA) en très bas âge. Je me demande souvent si des interventions non pharmacologiques pourraient prévenir ou atténuer le développement d’une DA. L’allaitement ou des changements dans l’alimentation maternelle aideraient-ils à prévenir le développement d’une DA infantile?

Réponse L’American Academy of Pediatrics fait valoir que les femmes qui allaitent des nourrissons à risque élevé de développer une DA devraient éviter les arachides et les noix, et envisager d’éliminer les œufs, le lait de vache et le poisson de leur alimentation. L’Organisation mondiale de la Santé recommande aussi d’allaiter les enfants jusqu’à l’âge de 2 ans. Des études ont démontré que l’allaitement pouvait avoir un effet de protection contre la DA chez l’enfant; toutefois, d’autres études ont trouvé des effets non significatifs ou inverses. Il faudrait plus de recherche à ce sujet.

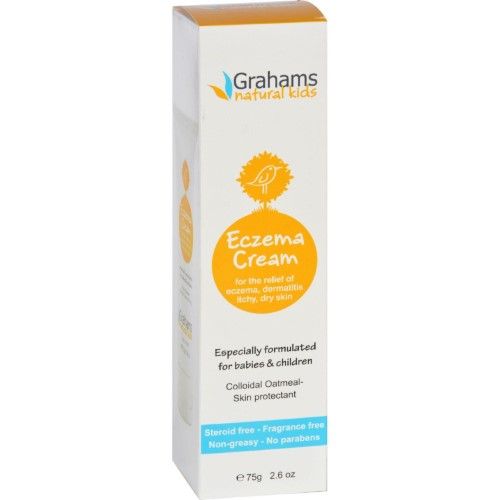

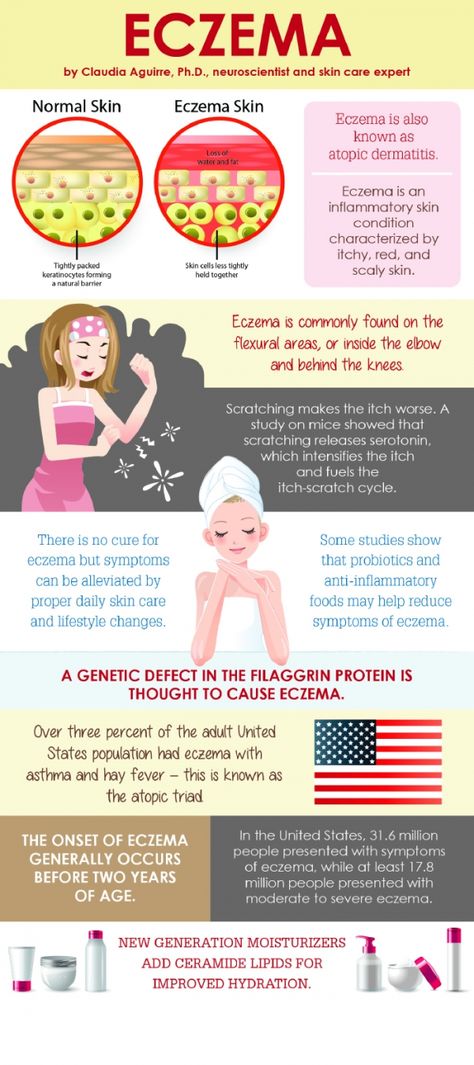

Eczema, a common, chronic, relapsing inflammation of the skin, is often seen in young children.1 Over the past 3 decades, the rate of eczema among children has increased, including the rate of atopic dermatitis (AD), one type of eczema.2 Some 20% of school-aged children in North America and 10% of children in Western Europe suffer from eczema.2 Similarly, incidence in other industrialized nations is about 20%.1

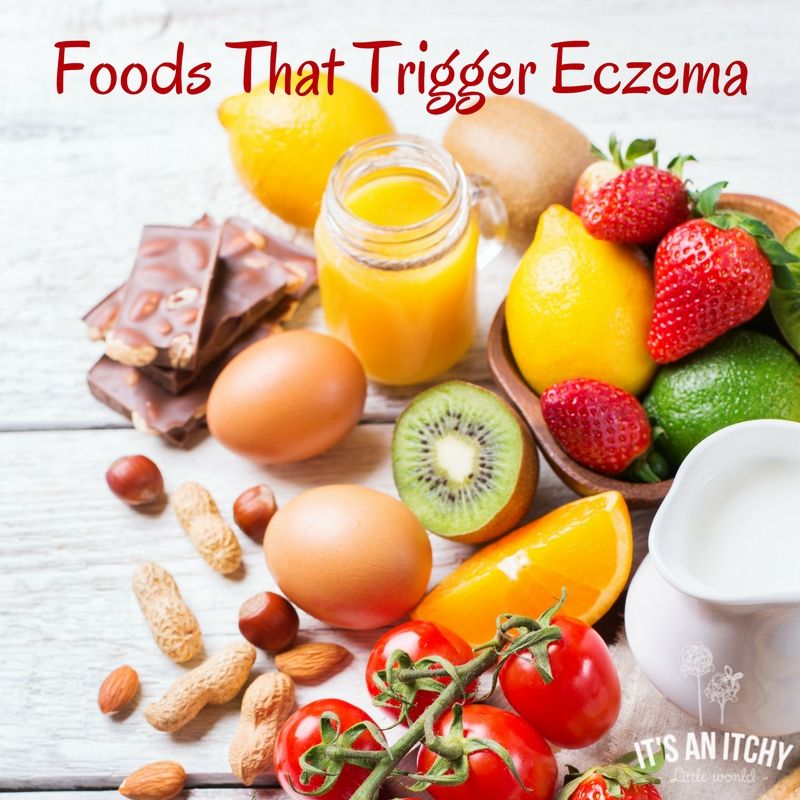

There is mounting evidence that genetic linkage and family history are risk factors for developing eczema,3 and it is essential to be able to provide sound advice to families. Although food has long been thought to cause or aggravate eczema, research on prevention of AD through early nutritional intervention is lacking.

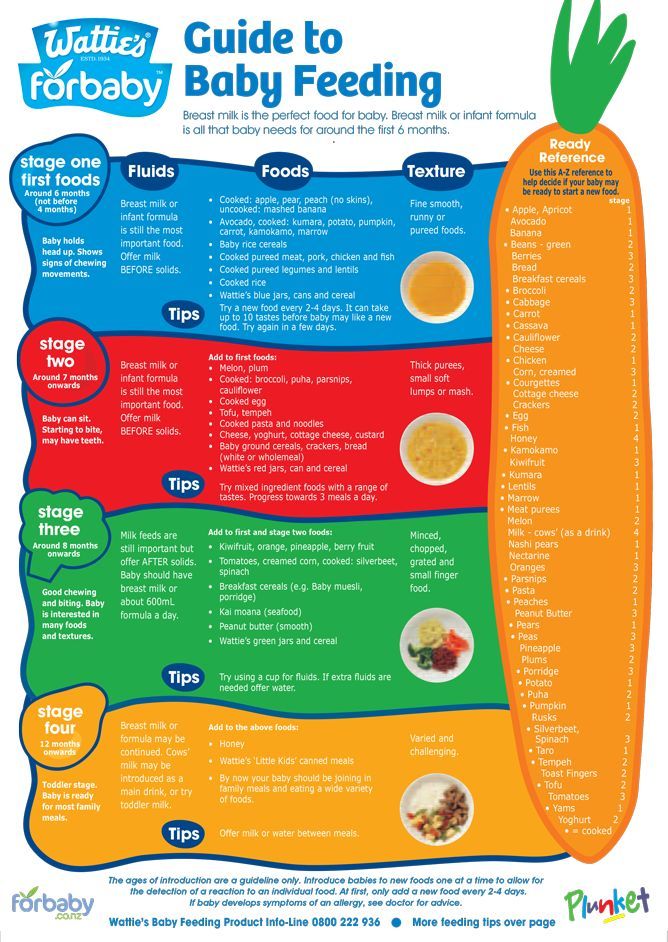

For many years, food has been considered a trigger for eczema, resulting in elimination diets, on occasion at the cost of malnutrition and emotional stress for children. 1 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the timing of introducing solid food can also affect the development of AD.4 It is recommended that initiating solid food be delayed until 4 to 6 months of age, and whole cow’s milk be delayed until 12 months of age.4

1 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the timing of introducing solid food can also affect the development of AD.4 It is recommended that initiating solid food be delayed until 4 to 6 months of age, and whole cow’s milk be delayed until 12 months of age.4

Several studies have evaluated the potential for hydrolyzed formula to reduce the risk of allergies compared with cow’s milk. In a randomized double-blind trial from the German Infant Nutritional Intervention study, among more than 2000 children offered hydrolyzed formulas from birth to 1 year of age, those offered extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (odds ratio [OR] 0.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.22 to 0.79) and partially hydrolyzed whey formula (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.99) had significantly reduced incidence of AD compared with those offered cow’s milk formula.5

In a Cochrane review comparing soy formula and cow’s milk formula, Osborn and Sinn6 included 3 studies with 875 infants 0 to 6 months of age without clinical evidence of allergy or food intolerance. After comparing the effect of adapted soy formula with human milk, cow’s milk formula, and hydrolyzed protein formula on the development of atopy, they found that soy formula offered no significant benefit in preventing infant eczema (relative risk 1.20, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.52).6

After comparing the effect of adapted soy formula with human milk, cow’s milk formula, and hydrolyzed protein formula on the development of atopy, they found that soy formula offered no significant benefit in preventing infant eczema (relative risk 1.20, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.52).6

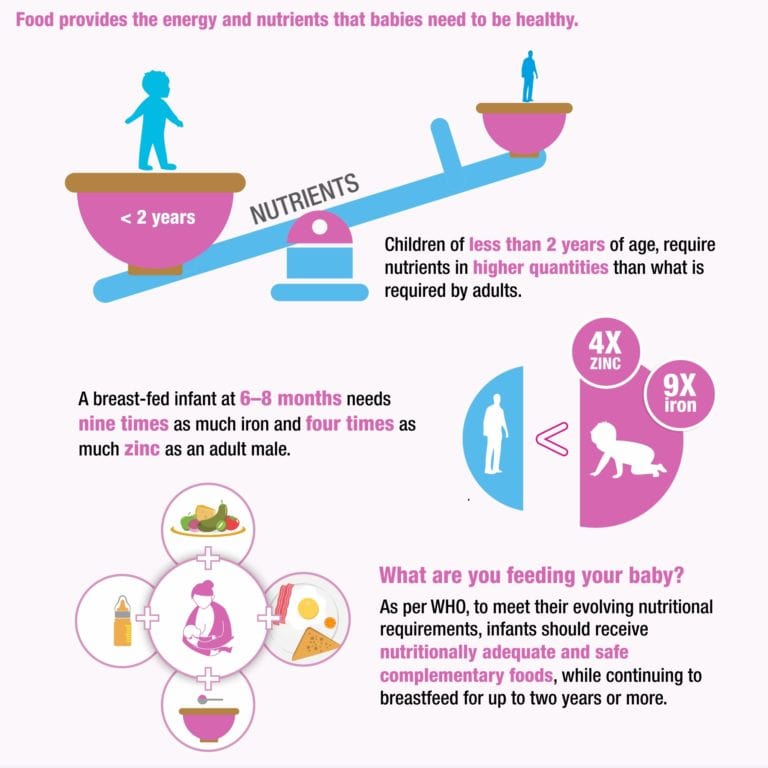

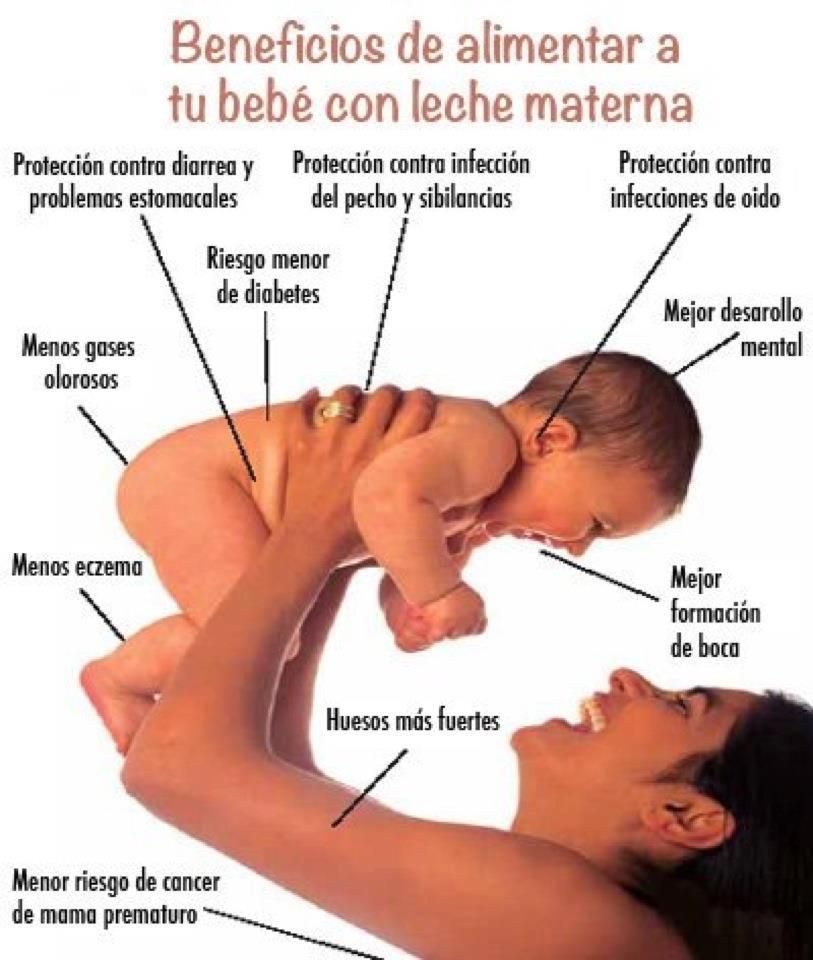

The World Health Organization currently recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and continuing to breastfeed, as well as introducing other foods, until 2 years of age.7 Breast milk contains compounds such as α-tocopherol, β-tocopherol, and prolactin—all help degrade inflammatory compounds, increase immune function, and decrease sensitivity of infants.8 In a meta-analysis of 18 prospective studies from 1966 to 2002, exclusive breastfeeding during the first 3 months of life was found to reduce the incidence of AD in children with a family history of atopy (OR 0.58, CI 0.41 to 0.92) and in those without a family history of atopy (OR 0. 84 for combined populations, CI 0.59 to 1.19).9 In another study, more than 2700 infants in the Netherlands were enrolled in a KOALA (Child, Parent, Health, Focus on Lifestyle and Predisposition) birth cohort study, in which it was found that breastfeeding could prevent atopic eczema in children.10 This study included repeated questionnaires at 34 weeks of gestation and at 3, 7, 12, and 24 months after birth, with immunoglobulin E levels measured at 2 years of age. Breastfeeding was found to prevent AD in the first 2 years of life among children of mothers without allergies and asthma.10 For mothers with allergies but no asthma, the results were not significant (P = .14) compared with mothers without allergies and asthma (P = .01), and there were no preventive effects when mothers had asthma (P = .87).10 Thus, it was concluded that breastfeeding had only negligible effects in children without first-order relatives who had atopy.

84 for combined populations, CI 0.59 to 1.19).9 In another study, more than 2700 infants in the Netherlands were enrolled in a KOALA (Child, Parent, Health, Focus on Lifestyle and Predisposition) birth cohort study, in which it was found that breastfeeding could prevent atopic eczema in children.10 This study included repeated questionnaires at 34 weeks of gestation and at 3, 7, 12, and 24 months after birth, with immunoglobulin E levels measured at 2 years of age. Breastfeeding was found to prevent AD in the first 2 years of life among children of mothers without allergies and asthma.10 For mothers with allergies but no asthma, the results were not significant (P = .14) compared with mothers without allergies and asthma (P = .01), and there were no preventive effects when mothers had asthma (P = .87).10 Thus, it was concluded that breastfeeding had only negligible effects in children without first-order relatives who had atopy. 10 In a birth cohort study conducted in Germany between 1995 and 1998, 3903 children were recruited, and exclusive breastfeeding was found to have a significant protective effect on AD prevention compared with cow’s milk formula (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90).11 In another prospective cohort study of healthy newborns at risk of atopy, 865 infants were exclusively breastfed and 256 infants were partially or exclusively formula fed, and were then followed for signs of AD or sensitization to milk or eggs for a year.12 The exclusively breastfed group had a lower incidence of AD (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.74). The recommendation for children with AD in the family was exclusive breastfeeding for at least 4 months to prevent AD in the first year of life.12

10 In a birth cohort study conducted in Germany between 1995 and 1998, 3903 children were recruited, and exclusive breastfeeding was found to have a significant protective effect on AD prevention compared with cow’s milk formula (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90).11 In another prospective cohort study of healthy newborns at risk of atopy, 865 infants were exclusively breastfed and 256 infants were partially or exclusively formula fed, and were then followed for signs of AD or sensitization to milk or eggs for a year.12 The exclusively breastfed group had a lower incidence of AD (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.74). The recommendation for children with AD in the family was exclusive breastfeeding for at least 4 months to prevent AD in the first year of life.12

However, breastfeeding effects on AD are still controversial. In a large population-based telephone cohort study in Denmark, Benn et al reported that exclusive breastfeeding for the first 4 months actually led to an increased incidence of AD in children with parents without allergies. 13 The association between breastfeeding and risk of AD seemed to increase with each month of exclusive breastfeeding.13 However, there was no dose-response effect found when comparing exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and 4 months.13 Another cross-sectional study from Japan among junior high-school students reported an increased AD incidence if children were fed breast milk in their first 3 months of infancy compared with formula (P = .03).14 This result was not significant among children with no parental history of allergy.14

13 The association between breastfeeding and risk of AD seemed to increase with each month of exclusive breastfeeding.13 However, there was no dose-response effect found when comparing exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and 4 months.13 Another cross-sectional study from Japan among junior high-school students reported an increased AD incidence if children were fed breast milk in their first 3 months of infancy compared with formula (P = .03).14 This result was not significant among children with no parental history of allergy.14

There are 2 possible ways to explain these findings. One possible reason is maternal awareness of the risk of developing AD, thus the increased risk of AD comes from atopic heredity as opposed to the effect of breast-feeding.13 Another explanation is the hygiene hypothesis.14 Early infection can promote maturation of the immune system and prevent further allergies, including eczema. 14 Because breastfeeding decreases the chance for children to be exposed to common allergens found in solid food or formulas, their immune systems will not be able to function properly to protect them from antigens, which might be the cause of more eczema cases found in the previous 2 studies. Although these hypotheses explain the increased incidence of AD seen in children with first-order parents with allergies, they cannot explain the increased risk of AD in children with parents without allergies.13

14 Because breastfeeding decreases the chance for children to be exposed to common allergens found in solid food or formulas, their immune systems will not be able to function properly to protect them from antigens, which might be the cause of more eczema cases found in the previous 2 studies. Although these hypotheses explain the increased incidence of AD seen in children with first-order parents with allergies, they cannot explain the increased risk of AD in children with parents without allergies.13

Can maternal dietary changes help infants avoid the risk of developing AD? In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggested that lactating mothers with infants at high risk of developing AD should avoid peanuts and tree nuts, and should consider eliminating eggs, cow’s milk, and fish from their diets.15 Food allergens such as peanuts have been detected in breast milk.14 However, in a cohort study of almost 14 000 preschool children, no association was demonstrated between breastfeeding and peanut allergy. 16 A Cochrane review of 4 trials with 334 pregnant women did not show adequate evidence that avoidance of eggs, milk, and other antigenic food in women during lactation prevented AD in children.17 The combined evidence from these trials does not show a strong correlation between maternal antigen avoidance and the incidence of AD in the first 18 months of life (relative risk 1.01, CI 0.39 to 12.67).17 A larger sample size and a longer follow-up study are needed to determine potential outcome benefits.17

16 A Cochrane review of 4 trials with 334 pregnant women did not show adequate evidence that avoidance of eggs, milk, and other antigenic food in women during lactation prevented AD in children.17 The combined evidence from these trials does not show a strong correlation between maternal antigen avoidance and the incidence of AD in the first 18 months of life (relative risk 1.01, CI 0.39 to 12.67).17 A larger sample size and a longer follow-up study are needed to determine potential outcome benefits.17

Other than focusing on antigenic foods, there has been increasing interest in the effects of probiotics as a maternal dietary supplement for preventing AD in children.18 In a Norwegian study, women received probiotic supplements during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy and until 3 months after birth.18 The results showed that the administration of probiotic bacteria significantly reduced the incidence of AD among children (OR 0. 51, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.87; P = .013).18 However, the results were not statistically significant in children with a positive family history.18 It was suggested that maternal supplementation with probiotics might influence the composition of the infant’s intestinal microbial flora and that such supplementation might be a potential mechanism for increasing anti-inflammatory immunoregulatory factors in breast milk.18 Other dietary supplements undergoing research are vitamin C19 and essential fatty acids.20 While there have been promising results for maternal intake of vitamin C,19 increasing the supplementation of omega-320 has not been found to reduce the incidence of AD among children.19,20 Further large-scale studies are required to explore these issues.19,20

51, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.87; P = .013).18 However, the results were not statistically significant in children with a positive family history.18 It was suggested that maternal supplementation with probiotics might influence the composition of the infant’s intestinal microbial flora and that such supplementation might be a potential mechanism for increasing anti-inflammatory immunoregulatory factors in breast milk.18 Other dietary supplements undergoing research are vitamin C19 and essential fatty acids.20 While there have been promising results for maternal intake of vitamin C,19 increasing the supplementation of omega-320 has not been found to reduce the incidence of AD among children.19,20 Further large-scale studies are required to explore these issues.19,20

The effects of breastfeeding and maternal diet on the development of AD in children are still controversial. While some reports suggest positive effects in preventing AD by breastfeeding or changing the maternal diet, other studies show insignificant or reverse effects. Further research is needed to determine sound recommendations for families.

While some reports suggest positive effects in preventing AD by breastfeeding or changing the maternal diet, other studies show insignificant or reverse effects. Further research is needed to determine sound recommendations for families.

PRETx

Child Health Update is produced by the Pediatric Research in Emergency Therapeutics (PRETx) program (www.pretx.org) at the BC Children’s Hospital in Vancouver, BC. Ms Lien is a member and Dr Goldman is Director of the PRETx program. The mission of the PRETx program is to promote child health through evidence-based research in therapeutics in pediatric emergency medicine.

Do you have questions about the effects of drugs, chemicals, radiation, or infections in children? We invite you to submit them to the PRETx program by fax at 604 875-2414; they will be addressed in future Child Health Updates. Published Child Health Updates are available on the Canadian Family Physician website (www. cfp.ca).

cfp.ca).

Competing interests

None declared

1. Finch J, Munhutu MN, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(6):605–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Eichenfield LF, Hanifin JM, Beck LA, Lemanske RF, Jr, Sampson HA, Weiss ST, et al. Atopic dermatitis and asthma: parallels in the evolution of treatment. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):608–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Snijders BEP, Stelma FF, Reijmerink NE, Thijs C, van der Steege G, Damoiseaux JGMC, et al. CD14 polymorphisms in mother and infant, soluble CD14 in breast milk and atopy development in the infant (KOALA study) Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(3):541–9. Epub 2009 Sep 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW, Committee on Nutrition and Section on Allergy and Immunology Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Von Berg A, Koletzko S, Grübl A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Wichmann HE, Bauer CP, et al. The effect of hydrolyzed cow’s milk formula for allergy prevention in the first year of life: the German Infant Nutritional Intervention study, a randomized double-blind trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(3):533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Osborn DA, Sinn J. Soy formula for prevention of allergy and food intolerance in infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. World Health Organization [website] Exclusive breastfeeding. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: www.who.int/nutrition/topics/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/. Accessed 2011 Jul 30. [Google Scholar]

8. Oddy WH. The long-term effects of breast-feeding on asthma and atopic disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;639:237–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Gdalevich M, Mimouni D, David M, Mimouni M. Breast-feeding and the onset of atopic dermatitis in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(4):520–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Breast-feeding and the onset of atopic dermatitis in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(4):520–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Snijders BE, Thijs C, Dagnelie PC, Stelma FF, Mommers M, Kummeling I, et al. Breast-feeding duration and infant atopic manifestations, by maternal allergic status, in the first 2 years of life (KOALA study) J Pediatr. 2007;151(4):347–51. 351.e1–2. Epub 2007 Jul 12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Laubereau B, Brockow I, Zirngibl A, Koletzko S, Gruebl A, von Berg A, et al. Effect of breast-feeding on the development of atopic dermatitis during the first 3 years of life: results from the GINI-birth cohort study. J Pediatr. 2004;144(5):602–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Schoetzau A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Franke K, Koletzko S, von Berg A, Gruebl A, et al. Effect of exclusive breast-feeding and early solid food avoidance on the incidence of atopic dermatitis in high-risk infants at 1 year of age. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(4):234–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(4):234–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Benn CS, Wohlfahrt J, Aaby P, Westergaard T, Benfeldt E, Michaelsen KF, et al. Breastfeeding and risk of atopic dermatitis, by parental history of allergy during the first 18 months of life. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(3):217–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Miyake Y, Yura A, Iki M. Breastfeeding and the prevalence of symptoms of allergic disorders in Japanese adolescents. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(3):312–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):346–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Lack G, Fox D, Northstone K, Golding J, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team Factors associated with the development of peanut allergy in childhood. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):977–85. Epub 2003 Mar 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Maternal dietary antigen avoidance during pregnancy or lactation, or both, for preventing or treating atopic disease in the child. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD000133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD000133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Dotterud CK, Storrø O, Johnsen R, Oien T. Probiotics in pregnant women to prevent allergic disease: a randomized, double-blind trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):616–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09889.x. Epub 2010 Jun 9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Hoppu U, Rinne M, Salo-Väänänen P, Lampi AM. Piironen, Isolauri E. Vitamin C in breast milk may reduce the risk of atopy in the infant. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(1):123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Dunstan JA, Mori TA, Barden A, Beilin LJ, Taylor AL, Holt PG, et al. Maternal fish oil supplementation in pregnancy reduces interleukin-13 levels in cord blood of infants at high risk of atopy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):442–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Your Baby's Diet and Eczema: Breastfeeding and Bottle-Feeding

Written by Stephanie Watson

Medically Reviewed by Dan Brennan, MD on December 17, 2018

When your baby has eczema, you may wonder if that itchy rash is related to your feeding style. Is breastfeeding to blame? Or is it the solid foods you just introduced?

Is breastfeeding to blame? Or is it the solid foods you just introduced?

Some simple tips can help you get your baby off to a healthy start.

Breast Milk or Formula?

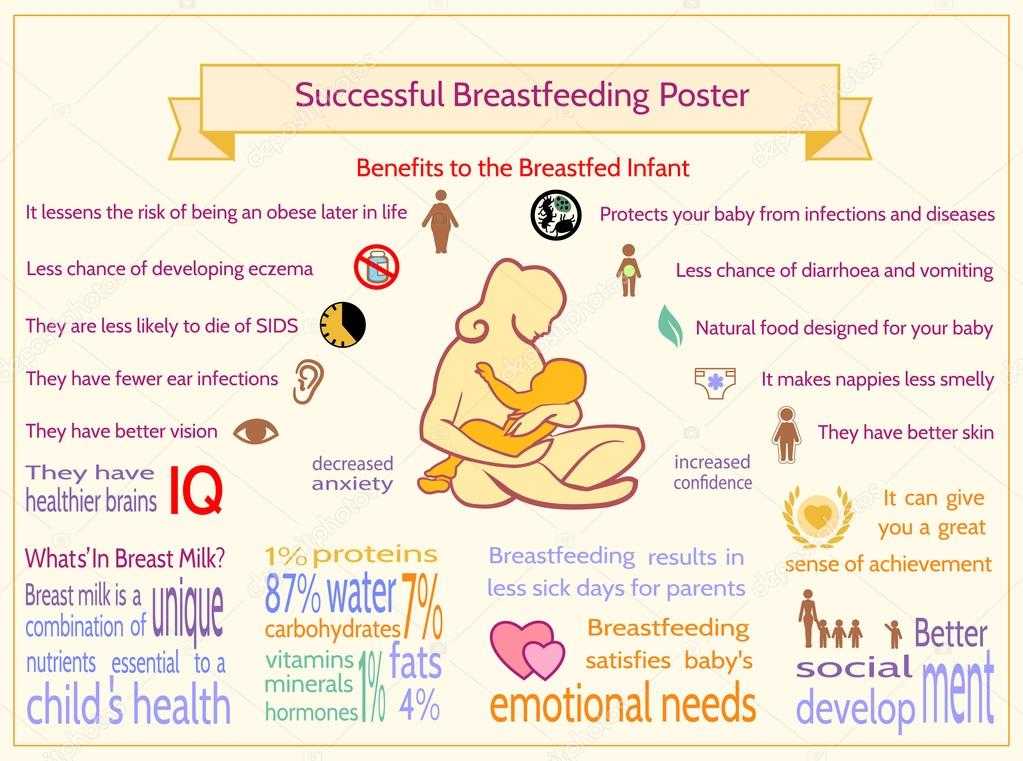

Breast milk is always best. It gives your little one the perfect balance of fat, protein, and other nutrients. It's also good for your baby's growing immune system.

"Breastfed infants will get some of the mom's immune system, so it actually helps boost their immunity," says Cindy Gellner, MD, a pediatrician at the University of Utah Community Clinics.

Breastfeeding also helps make the immune system less sensitive. That's important for eczema, which is triggered by overactive defenses.

Can a Breastfeeding Mom's Diet Affect Their Baby's Eczema?

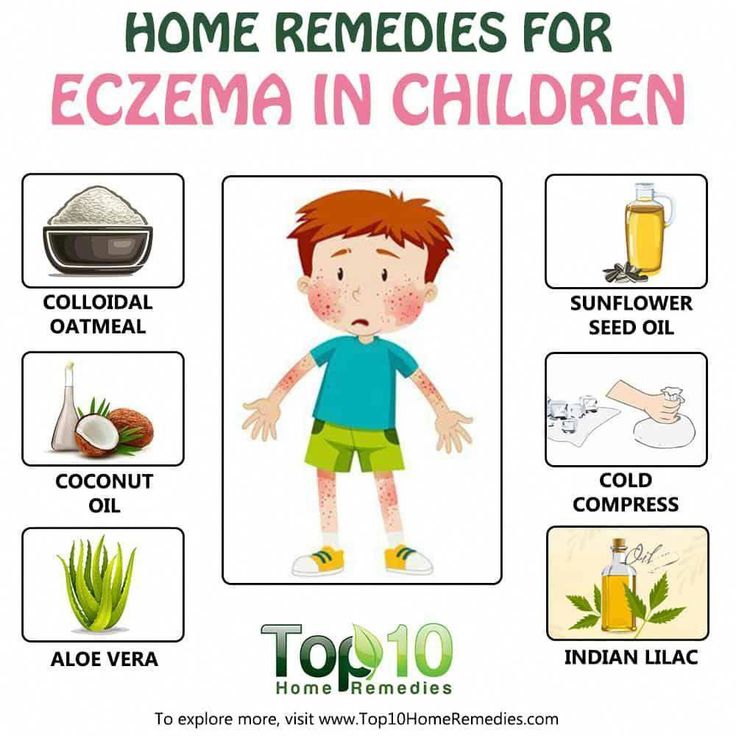

Certain foods in a mom's diet could cause problems for their baby with eczema. If you’re breastfeeding, you may want to avoid common triggers like:

- Cow's milk

- Peanuts

- Tree nuts

- Shellfish

Signs that your baby is having a reaction to something you ate include an itchy red rash on the chest and cheeks, and hives. If you see these, stay away from whatever you think may be causing the problem for a couple of weeks.

If you see these, stay away from whatever you think may be causing the problem for a couple of weeks.

If things get better, brings foods back one at a time, says Robert Roberts, MD, PhD, a professor of pediatrics at UCLA.

Get some help from your doctor so you'll know when it's safe to start eating those foods again.

Which Formula Is Best for Bottle-Feeding?

"All babies will start off on milk-based formula," Gellner says. "If the baby has a lot of eczema and it's really problematic, then we'll try switching them to a formula made with hydrolyzed proteins."

Hydrolyzed means that the milk proteins are already broken down, so they're less likely to trigger an allergic reaction.

When Should You Introduce Solid Foods?

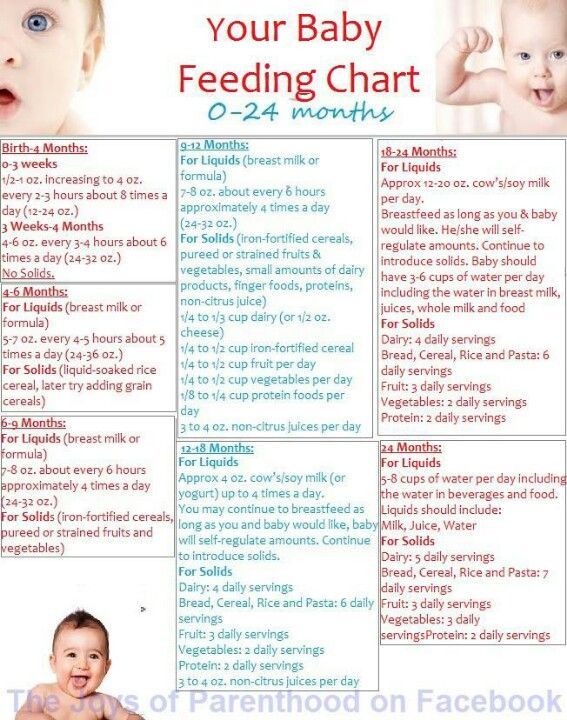

Experts say you can start your baby on solids between 4 and 6 months old. Ask your pediatrician what age is best for your child.

Which Foods Should You Give Your Baby First?

Many parents start their babies with iron-fortified rice or oatmeal cereals, and then graduate them to fruits and vegetables. Still, it's perfectly fine to start your kid on stage 1 fruits and vegetables or puree a veggie or fruit yourself.

Still, it's perfectly fine to start your kid on stage 1 fruits and vegetables or puree a veggie or fruit yourself.

"The biggest issue for parents of children with eczema is they need to introduce one food at a time so they can know what is causing a problem," says Chris Adigun, MD, a clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the New York University School of Medicine. "Stick with that food for at least 4 or 5 days before you move on to the next food."

After each new one, watch out for signs of an allergy, like:

- Diarrhea, sometimes with blood

- Hives

- Rash

- Swelling of the lips or tongue

- Vomiting

If you see any of these, call your child's doctor.

When Can Your Child Start on Cow's Milk?

Around 1 year old, you can try giving your child whole milk. If you notice any skin problems, then ask your doctor if you should switch to soy milk.

Food Allergies in Children - Mom's Club. All About Pregnancy, Baby & Toddler Development

Signs, Symptoms and Helpful Hints

Having a food allergy can cause severe symptoms and affect your baby's nutritional intake. Find out what signs to look out for, which foods are most likely to cause an allergic reaction, how and when it's safe to introduce allergenic foods to your diet, and why breastfeeding can help reduce your baby's risk of allergies.

Find out what signs to look out for, which foods are most likely to cause an allergic reaction, how and when it's safe to introduce allergenic foods to your diet, and why breastfeeding can help reduce your baby's risk of allergies.

Food allergies in newborns and infants

A food allergy is an overreaction of the immune system to a specific substance. Symptoms of the onset of an allergic reaction can be rapid, obvious and occur immediately after eating, or delayed in the form of longer-term or recurring symptoms such as eczema and digestive problems.

Food allergies are more common in toddlers than adults and affect approximately 6-8% of children at an early age. It is reassuring to know that many children eventually outgrow their allergies.

Food Allergy Detection

As you introduce solid foods into your baby's diet, you will no doubt notice what foods your baby likes and doesn't like. However, it is more important to watch for any signs of a food allergy. Only 1 in 17 children suffer from food allergies, and most babies will never develop any of the allergic symptoms.

Only 1 in 17 children suffer from food allergies, and most babies will never develop any of the allergic symptoms.

The most common symptoms of a fast food allergy are:

-

swelling of the eyes and lips;

-

diarrhea or vomiting;

-

wheezing, runny nose, red eyes and sneezing;

-

itching, urticaria and atopic dermatitis

Allergy symptoms can be mild, moderate or severe. And while it seems that some people experience allergy symptoms of the same severity every time they have an allergic reaction, there is no guarantee that a mild reaction in one case will not lead to a more severe reaction in another. This is why it is so important to diagnose and treat allergies in children and prevent them from developing.

A severe, rapid, life-threatening allergic reaction is called an anaphylactic reaction. Severe wheezing in the chest, difficulty breathing, Quincke's edema, itching of the whole body, urticaria, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dizziness, loss of consciousness may be signs of anaphylactic shock, which requires emergency medical care. Fortunately, this type of allergic reaction is rare.

Fortunately, this type of allergic reaction is rare.

Allergic foods

Foods that cause allergic reactions more often than others:

-

milk;

-

eggs;

-

wheat products;

-

soy;

-

fish;

-

seafood;

-

peanuts;

-

nuts.

Heredity

If you are currently pregnant and have allergies, you may be worried about your child developing allergies as well. The transmission of a predisposition to allergies is from 30 to 50% if one of the parents is allergic, but if both parents are allergic, the risk increases even more. In this regard, it is advisable to have an idea about other types of allergic reactions, including allergies to cow's milk, in case your baby suddenly appears. If no one in your family has allergies, the risk of your child developing allergies is much less—in this case, only 10% of children.

Introducing allergenic foods into the diet

Allergenic foods will appear in his diet.

If you are breastfeeding, continue breastfeeding during the first year of life, if possible, in parallel with the introduction of complementary foods to reduce the risk of developing allergies.

Start with a small amount of the allergenic product and wait a few days before introducing another product of any kind. If your child has a reaction, you can easily determine which food is causing the symptoms. If you suspect that your baby has an allergy, talk to your doctor who can diagnose your baby and offer solutions on how to manage the symptoms of the disease.

Keep track of your baby's health

It can take time to learn all about allergies and what foods your child can and cannot eat. While you're in the process of learning this information, read the labels carefully, even for products you didn't know might contain an allergen you should avoid.

Food labeling legislation makes it easier to find allergens in your baby's diet.

Depending on the food your child is allergic to, cutting it out of the diet can put you at risk for a deficiency in essential nutrients. The right decision is to see a doctor to make sure your child is getting the full range of nutrients needed for growth and development.

The role of breast milk in reducing the risk of developing allergies

Experts agree that breastfeeding helps protect babies from developing allergies. This comes at the expense of supporting their immature immune system, as breast milk is rich in antibodies that provide protection for the baby in the first months of life. Breastfeeding helps reduce exposure to allergenic foods early in life and promotes the development of the gastrointestinal tract and gut microbiota.

Breastfeeding or feeding expressed breast milk from a bottle for at least the first 4-6 months of your baby's life can reduce the risk of developing allergies.

Effects of antibiotic therapy on the gut microbiota

Antibiotics are now widely used to kill bacteria that cause disease.

DETAILS

Cow's Milk Protein Allergy (CMP) Treatment FAQ

Effective treatment of CMPA requires a complete abstention from cow's milk and cow's...

DETAILS

Caesarean section and the development of the intestinal microbiota in the child

Every child is unique. As parents, you strive to provide your baby with the best conditions for development, taking into account ...

DETAILS

My child has allergies - now what?

If your child has an allergic reaction to certain foods, you should talk to your pediatrician.

DETAILS

Hypoallergenic milk formula when breastfeeding is not possible: for or against?

If breastfeeding a baby with allergies is not possible, the doctor may recommend using. ..

..

DETAILS

How can food labeling help you with your child's allergies?

If your child has a food allergy, you can't afford to skimp on the details.

DETAILS

Elimination diet for a child with a food allergy

In a child with a food allergy, the symptoms and possible harm it causes mainly occur in...

DETAILS

How do you manage your child's food allergies?

Being diagnosed with a food allergy does not necessarily mean that your child will now be perceived as "different" or excluded...

DETAILS

What to do if you think your baby is allergic to cow's milk

If your baby seems to be having an adverse reaction after breastfeeding, bottle feeding...

DETAILS

Recognizing signs of milk allergy and milk intolerance in children

From stomach cramps to nausea and diarrhea, the symptoms of milk intolerance and milk allergy are very similar.

DETAILS

Allergy symptoms

Cow's milk allergy has a wide variety of manifestations, and its symptoms are non-specific ...

DETAILS

Will your baby develop allergies?

If you or your partner have an allergy, you may be worried that your child will develop it too.

DETAILS

Where does food allergy come from?

The development of allergies in young children can depend on many factors. The most significant of them is genetic...

DETAILS

Tips for Avoiding Allergies

Did you know that approximately 20-30% of children have allergies? One of the most significant factors contributing to the development of...

DETAILS

Strong immune system - less chance for allergies

The good news is that allergies can be prevented. If there is a history of allergies in your family, the chances are that your child has...

If there is a history of allergies in your family, the chances are that your child has...

DETAILS

Allergy Risk Test

Did you know that 30-40 percent of babies are at risk of developing allergies? Take this assessment test to find out...

DETAILS

Expanding the child's diet and preventing food allergies

Expanding a child's diet is a problem for parents. The greatest concern is the introduction into the children's diet ...

DETAILS

Bifidobacterium breve: what is it and where does it come from?

Natural childbirth and breastfeeding have a beneficial effect on the formation of the intestinal microbiota ...

DETAILS

4 steps to protect your child from allergies

If you have allergies and are expecting a baby, you may be worried about your baby becoming allergic.

DETAILS

Good to know about MILK ALLERGY (melk)

MILK ALLERGY

Useful information about milk allergy – Information sheet of the Norwegian Asthma and Allergy Association

What is milk allergy?

When allergic to cow's milk protein, a strong reaction of the body's immune system may be the production of antibodies (IgE), or the activation of inflammatory cells. With every meal containing milk proteins, an allergic reaction of the immune system is observed in the form of the production of mediators, such as histamine, or a T-cell inflammatory reaction. Histamine is produced in several places in the body and leads to symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, or skin lesions (urticaria, eczema).

Cow's milk contains over 25 different proteins that can cause a reaction in "milk" allergies. For most people, an allergic reaction can be caused by more than one type of protein. The milk of other artiodactyls such as goat, horse and buffalo contains many of the same proteins. Therefore, allergy sufferers should not consume artiodactyl milk at all.

The milk of other artiodactyls such as goat, horse and buffalo contains many of the same proteins. Therefore, allergy sufferers should not consume artiodactyl milk at all.

If a breastfeeding mother consumes cow's milk herself, some proteins may be transferred with breast milk to the baby's body and lead to negative consequences. Therefore, a breastfeeding mother should follow a dairy-free diet.

Cow's milk allergy is not the same as lactose intolerance. The latter occurs due to the reduced ability of the body to digest milk sugar (lactose). Lactose intolerance leads to stomach pain and diarrhea as a consequence of eating large amounts of dairy products with high levels of lactose (sweet milk, brown (goat) cheese, ice cream and cream).

Symptoms

The symptoms of a milk allergy are very individual. For some, they are minor and harmless, while for others, a severe allergic reaction can occur, even when drinking a small amount of milk. Gastrointestinal tract disorder is common. Not so often there is itching in the mouth and throat, swelling of the mucous membrane and breathing problems, which is especially true for young children. It is also common for them to develop eczema and hives on the skin.

Not so often there is itching in the mouth and throat, swelling of the mucous membrane and breathing problems, which is especially true for young children. It is also common for them to develop eczema and hives on the skin.

Who is affected?

Milk allergy is the most common type of allergy in young children, which is explained by the early introduction of cow's milk into the diet of infants (eg cereals or mother's milk substitute). About 2-5% of Norwegian babies (0-3 years old) suffer from this type of allergy.

Diagnosis

In order to determine the presence of a milk allergy, the doctor must read the patient's medical history, as well as take a blood test for allergic antibodies and a Pirquet test. Not all milk allergy sufferers will show positive results from these tests. This is especially true for infants with symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, or blood in the stool. The only reliable way to find out if milk causes these symptoms is to eliminate milk from the diet for a period of time. When in doubt, reintroduce it back into the diet and see if symptoms return. For children who have not received milk for some time due to allergies, a control test using cow's milk should be performed to ensure that there is no allergic reaction.

When in doubt, reintroduce it back into the diet and see if symptoms return. For children who have not received milk for some time due to allergies, a control test using cow's milk should be performed to ensure that there is no allergic reaction.

Predictions

Generally, cow's milk allergy has a fairly good prognosis. Most of the children get rid of it before reaching school age. Babies who have had negative test results are often allowed to resume milk intake after half a year or a year. It is not known how many adults suffer from milk allergy, but it is estimated that this number does not exceed one percent of the population.

Where is milk protein found?

Milk is found in many processed and prepared industrial foods. Therefore, when buying a product, it is important to familiarize yourself with the list of substances contained in it. The goods declaration must list all ingredients containing milk. A certain group of words used in such lists indicates the content of milk protein in the product:

Cream fresh, cream, ice cream, casein, caseinate, cheese, lactalbumin, margarine, whey, whey powder, cheese, cheese powder, sour cream, butter, yogurt, yogurt powder.

Cocoa butter, lactic acids and group E substances do not contain milk protein.

Diet

Milk is an important source of nutrients in the Norwegian diet. 25% of the protein given to children, 70% of the iodine and about 70% of the calcium are obtained from dairy products. That is why, in cases of exclusion of dairy products from the diet, these products should be replaced with others that will provide the intake of the above nutrients. Alternatively, specially formulated additives can be used.

What can replace milk?

- Beverages: Hypoallergenic milk replacer is recommended for small children and is available from the pharmacy. These products can be purchased at a pharmacy or obtained from a blue prescription (prescription prescription). Because older children can be difficult to accustom to these milk substitutes due to their taste, it is recommended to start using substitutes as early as possible, for example during breastfeeding.