Nestle baby food africa

Nestle's Infant Formula Scandal

Nestle's Infant Formula Scandal Search iconA magnifying glass. It indicates, "Click to perform a search". Insider logoThe word "Insider".US Markets Loading... H M S In the news

Chevron iconIt indicates an expandable section or menu, or sometimes previous / next navigation options.HOMEPAGEFinance

Save Article IconA bookmarkShare iconAn curved arrow pointing right.Download the app

Baby Milk Action pdf inspired us to look into the dubious history of this product.

Outrage started in the 1970s, when Nestle was accused of getting third world mothers hooked on formula, which is less healthy and more expensive than breast milk.

The allegations led to hearings in the Senate and the World Health Organization, resulting in a new set of marketing rules.

Yet infant formula remains a $11.5-billion-and-growing market.

'The Baby Killer' blew the lid off the formula industry in 1974.

Baby Milk Action pdfSocial rights groups began dragging the industry's exploitative practices into the spotlight in the early 1970s.

The New Internationalist published an exposé on Nestlé's marketing practices in 1973, "Babies Mean Business," which described how the company got Third World mothers hooked on baby formula.

But it was "The Baby Killer," a booklet published by London's War On Want organization in 1974, that really blew the lid off the baby formula industry.

Nestlé was accused of getting Third World mothers hooked on formula

YouTube / All About IBFANNevermind that these women lived in squalor and struggling to survive.

In poverty-stricken cities in Asia, Africa and Latin America, "babies are dying because their mothers bottle feed them with Western-style infant milk," alleged War on Want.

Nestlé accomplished this in three ways, said New Internationalist:

- Creating a need where none existed.

- Convincing consumers the products were indispensable.

- Linking products with the most desirable and unattainable concepts—then giving a sample.

Meanwhile, research was proving breastfeeding was healthier.

Flickr"At the same time, the benefits of breastfeeding were being brought to light," Paige Harrigan a senior nutrition advisor with Save the Children, told Business Insider.

Vitamin A prevents blindness and lowers a child's risk of death from common diseases, while zinc might stave off diarrhea, according to the organization's State of the World Report. Six months of exclusive breastfeeding are said to increase a child's chance of survival by six times.

Still, third world women yearned for Westernization.

Flickr / x-ray delta onePoor women longed to move from a rural to an urban way of life, which prodded them to abandon breastfeeding and in turn primed them for marketing, said War on Want:

"As the social position of women changes and they go out to earn a wage . .. looking at the breast as a cosmetic sex symbol rather than a source of nourishment reinforces the trend."

.. looking at the breast as a cosmetic sex symbol rather than a source of nourishment reinforces the trend."

War on Want said this undermined women's confidence in breastfeeding.

YouTube / All About IBFANPlaying into undernourished women's fear of harming their newborn was a "confidence trick," said War on Want. When these women felt fear, pain or sadness, their milk would dry up as a result.

The "letdown reflex, which controls the flow of milk to the mother's nipple is a nervous mechanism," the paper said. "Somehow mothers are deciding that a bottle is necessary to the milk she provides ... some mothers may even become so concerned about not having enough milk that they will not have enough."

"Somehow mothers are deciding that a bottle is necessary to the milk she provides ... some mothers may even become so concerned about not having enough milk that they will not have enough."

Hospitals were also accused of pushing mothers to use formula.

YouTube / All About IBFANThis worked on two levels, said New Internationalist: In exchange for handing out "discharge packs" of formula, hospitals received freebies like formula and baby bottles.

"The most insidious of these is a free architectural service to hospitals which are building or renovating facilities for newborn care," the authors wrote.

Beyond that, the authors said "baby milk companies spend untold millions of dollars subsidizing office furnishings, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications and travel junkets of the medical profession."

Meanwhile in the Third World, women tried to save money by diluting the formula.

YouTube / All About IBFANFormulas had to be mixed with water, but Third World mothers didn't understand that overdilluting it—especially with contaminated water—could "prevent a child from absorbing the nutrients in food and lead to malnutrition," said War on Want.

A New York Times' article on the scandal said one Jamaican family's income "averaged only $7 a week," leading the mother to dilute the water with as much as three times the recommended amount of water so she could feed two children.

Millions of babies died from malnutrition.

YouTube / All About IBFAN"The results can be seen in the clinics and hospitals, the slums and graveyards of the Third World," said War on Want. "Children whose bodies have wasted away until all that is left is a big head on top of the shriveled body of an old man. "

"

In the Times, United States Agency for International Development official, Dr. Stephen Joseph, blamed reliance on baby formula for a million infant deaths every year through malnutrition and diarrheal diseases.

It also hindered infant growth in general, said War on Want. Citing "complex links emerging between breast feeding and emotional and physical development," the group said breastfed children walked "significantly better than bottle-fed" kids, and were more emotionally advanced.

Nestlé sued a War On Want publisher for libel in 1974.

GettyNestlé wasn't about to take these allegations lying down. It sued a German translator of War on Want's exposé, which published it in Sweden with the title, "Nestlé Kills Babies."

It sued a German translator of War on Want's exposé, which published it in Sweden with the title, "Nestlé Kills Babies."

Nestlé won the suit in 1976, said Baby Milk Action , but with a caveat: The judge urged them to "modify its publicity methods fundamentally." Time Magazine declared this a "moral victory" for consumers.

The bad publicity sparked a global boycott of Nestlé.

YouTube / All About IBFANInfant Formula Action Coalition launched a boycott in the U.S. protesting Nestlé. Soon it spread to France, Finland and Norway and countless other countries.

"I remember my mother telling me about this and in 1980, she refused to buy candy bars because we heard of so many kids dying in the news stories," said Harrigan.

The boycott was suspended in 1984, but resurfaced in the late 1980s when Ireland, Australia, Mexico, Sweden and the U.K. adopted it.

Source: Baby Milk Action

The International Code of Marketing Breast-Milk Substitutes was created in 1981.

YouTube / All About IBFANIn 1978, Senator Edward Kennedy held a series of U. S. Senate Hearings on the industry's unethical marketing practices. International meetings with the World Health Organization, Unicef and The International Baby Food Action Network followed.

S. Senate Hearings on the industry's unethical marketing practices. International meetings with the World Health Organization, Unicef and The International Baby Food Action Network followed.

By 1981, the 34th World Health Assemblyhad adopted Resolution WHA34.22, which includes the International Code of Marketing Breast-Milk Substitutes.

Celebrities like this British TV host joined the breastfeeding cause in the 1990s.

YouTube / The Mark Thomas ProductBritain's "The Mark Thomas Product" show skewered Nestlé in 1999 when its host asked heads of the company why they misrepresented their products—and labeled them in English. Didn't this take advantage of the poor and illiterate?

Didn't this take advantage of the poor and illiterate?

Here, Mark Thomas asks a "tin of baby milk from Mozambique" isn't written in Portuguese, the country's official language.

According to Baby Milk Action, Emma Thompson famously called for a boycott of the Perrier Comedy Award in 2001 since the beverage is owned by Nestlé. The following year, the Tap Water Awards were established.

Today, breastfeeding and formula remain a hot topic.

NYC Dept of Health and Mental HygieneRecently, NYC Mayor Bloomberg launched the Latch On, NYC iniative which aims to do away with formula in hospitals.

"From what I can tell, it's using the a lot of provisions in the code," said Harrigan.

Not even your kitchen is safe ...

Flickr / Nomadic LassRead next

LoadingSomething is loading.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you're on the go.

Features Personal Finance NestleMore...

Nestlé baby milk scandal has grown up but not gone away | Guardian sustainable business

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, I gave Nestlé chair Peter Brabeck, a present – an original, signed copy of The Baby Killer, the 1974 report that I wrote for War on Want.

The Baby Killer explained how multinational milk companies like his were causing infant illness and death in poor communities by promoting bottle feeding and discouraging breast feeding.

Our Swiss associates were less subtle. They titled the report "Nestlé Toten Babies" (or Nestlé Kills Babies), which a Swiss court found was libelous. On the substance of the argument, however, the judge warned Nestlé that if the company did not want to face accusations of causing death and illness through sales practices such as using sales reps dressed in nurses' uniforms, they should change the way that they did business.

That shocked the company and undermined its benevolent self-image. It also launched a long-running global campaign, proving that networked social action was possible even in snail mail days.

Nestlé boycotts spread from Switzerland and Britain to the US, where shareholder activism and court challenges against other milk companies – led by the Sisters of the Precious Blood, a religious order working under the umbrella of the Interfaith Centre for Corporate Responsibility – achieved a fine balance between grassroots organising, legal process and catchy communication.

The campaigns attracted wide-spread support from medical professionals, health authorities and civil society in developing countries. So in 1981, the UN World Health Assembly (the governing body of the World Health Organisation) recommended the adoption of an international code of conduct to govern the promotion and sale of breast milk substitutes. Global regulation of consumer industries was – and remains – a threat to business. UN resolutions are "soft law" that have little direct effect, yet often lead to hard national enforcement.

Back then, Nestlé's response was that their critics should focus on doing something to improve unsafe water supplies, which contributed to the health problems associated with bottle feeding. I spent 30 years doing just that in Mozambique, South Africa and elsewhere. So it was appropriate that water brought me together with Brabeck.

I don't like the way companies such as Nestlé promote bottled water, turning one of life's essentials into a brand that only the better-off can afford and undermining the value of public supplies in the process. But I have to acknowledge Brabeck's efforts to get business and governments to work together to manage and protect the world's vital water resources.

But I have to acknowledge Brabeck's efforts to get business and governments to work together to manage and protect the world's vital water resources.

However, for Nestlé and the rest of the global food industry, the baby milk scandal has grown up rather than gone away. The industry today stands accused of harming the health of whole nations, not just their babies. New York mayor Michael Bloomberg has committed his own money to a campaign against unhealthy food, comparing this to his fight against the tobacco industry. The WHO faces opposition to proposals from the NGO Global Action for Improved Nutitrion to establish partnerships with industry. What started as skirmish in the nursery is turning into full-scale war on many fronts.

While the diseases are now obesity, diabetes and heart disease, the issues about the food industry's responsibility remain the same: its huge marketing budgets clearly influence peoples' behaviour, even if direct causality can't be demonstrated. Children and young adults may get fat because they do not get enough exercise. But if they are offered and encouraged to "choose" super-saturated fat diets, dosed with excessive salt and drinks laced with multiple sugars, can the industries that produce and promote those products absolve themselves from the ugly outcomes? Back in the 1970s, the Swiss judge ruled to the contrary. Today public and political opinion is again swinging in that direction.

But if they are offered and encouraged to "choose" super-saturated fat diets, dosed with excessive salt and drinks laced with multiple sugars, can the industries that produce and promote those products absolve themselves from the ugly outcomes? Back in the 1970s, the Swiss judge ruled to the contrary. Today public and political opinion is again swinging in that direction.

Important questions are being raised in discussions about the new global development goals to be adopted when the UN's current Millennium Development Goals 'expire' in 2015. Should sustainable development goals focus on the unsustainable and unhealthy lifestyles of the rich as well as on the plight and basic needs of the poor? As the world searches for better measures of development than gross domestic product (GDP), counting dead babies remains an important indicator. But if infant mortality was a stark indicator of poor infant feeding practices in the 1970s, gross obesity is a parallel indicator of poor nutrition today. And action to control the products and marketing of large food companies are an obvious means to improve people's health.

And action to control the products and marketing of large food companies are an obvious means to improve people's health.

So the spectre of global regulation still looms, an existential issue for the global food companies. "Ethical investors" now turn for guidance to the FTSE 4 Good index, which screens company behaviour. But there will need to be more explicit codes of practice and the political will to enforce them if shareholder action is to be effective. If global companies are to produce and promote healthier food and treat their suppliers more fairly and remain market leaders, such standards must also be enforced or cheap unregulated competition will inevitably undermine those who comply.

Critics of the global food business also face challenges. Realists know that a return to a bucolic world of trusted small-scale local food production cannot meet the needs of seven billion people today and more tomorrow. But should activists build on existing regulatory platforms by raising the bar, setting new standards and mobilising shareholders to promote a more responsible and accountable global food industry? Or should they take a more aggressive approach to monitoring and acting directly against damaging behaviour? We will probably see a mix of both strategies, making the food business a challenging place to be over the next few years.

Back in Davos, my dedication to Brabeck was simple. Reading the Baby Killer report today showed that we had made progress since the 1970s, I said. I thanked him for his support on the global water agenda, and I meant it. Of course there are many places around the world where Nestlé's operations are challenged by workers and communities, for many valid reasons. But in an imperfect world, at least some of the immediate issues are now on the table for public discussion and he has helped to put them there. I could perhaps have added the Mozambican adaptation of that old revolutionary slogan: "Victory continues – the struggle is certain". But, however accurate, that would have spoilt the moment.

Mike Muller is an engineer, writer and development specialist. Currently a member of South Africa's National Planning Commission, he is also a visiting professor of public and development management at the University of the Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg. As director general of South Africa's Department of Water Affairs, he designed and led a programme that has brought safe water to over 16 million people since 1994

As director general of South Africa's Department of Water Affairs, he designed and led a programme that has brought safe water to over 16 million people since 1994

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. Become a GSB member to get more stories like this direct to your inbox

Why is Nestlé baby food not finding adequate demand?

According to Euromonitor, in 2018, the largest growth in sales in the infant formula segment came from specially formulated foods for babies who have just transitioned from breastfeeding to formula. 123rf.comSwiss food giant Nestlé is trying to diversify its baby food range and bring innovative products to market. The prospects here are promising. However, many critics are skeptical. And they have a reason to.

This content was published on January 10, 2020 - 11:00Jessica Davis Pluss (Jessica Davis Pluss)

In the first weeks of life, baby Lindsay Beeson developed a rash, traces of blood on diapers, diarrhea and vomiting. Doctors diagnosed an allergy to cow's milk. Like many other mothers in her situation, Lindsey eliminated milk from her baby's diet and, in addition to breastfeeding, began to gradually introduce complementary foods with hypoallergenic infant formula. In the second year of his life, her son was switched to milk formulas specially designed for babies with allergies. “I knew that they contained a balance of proteins, fats and vitamins similar to the composition of cow's milk. And my son liked the taste,” she said in an interview with swissinfo.ch.

Doctors diagnosed an allergy to cow's milk. Like many other mothers in her situation, Lindsey eliminated milk from her baby's diet and, in addition to breastfeeding, began to gradually introduce complementary foods with hypoallergenic infant formula. In the second year of his life, her son was switched to milk formulas specially designed for babies with allergies. “I knew that they contained a balance of proteins, fats and vitamins similar to the composition of cow's milk. And my son liked the taste,” she said in an interview with swissinfo.ch.

Show more

For global food concerns such as Nestlé, the development and launch of new formulas for infants up to one year of age, including those suffering from allergic reactions, requiring special dietary nutrition or simply picky eaters, is another and very important abroad in expanding the range of baby food.

Speaking to a group of journalists in Lausanne, Thierry Philardeau, Nestlé's Senior Vice President of Strategic Dairy Business Development, recently stated: all babies and their mothers. " From a practical point of view, the concern's strategy is to fill the gaps that arise in the nutrition of mothers and their children, regardless of whether the children receive artificial feeding, natural breastfeeding or combination.

" From a practical point of view, the concern's strategy is to fill the gaps that arise in the nutrition of mothers and their children, regardless of whether the children receive artificial feeding, natural breastfeeding or combination.

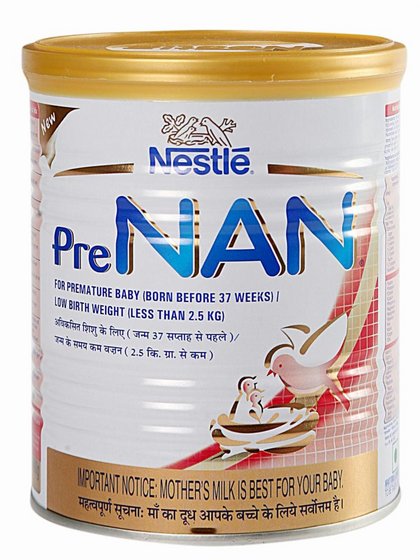

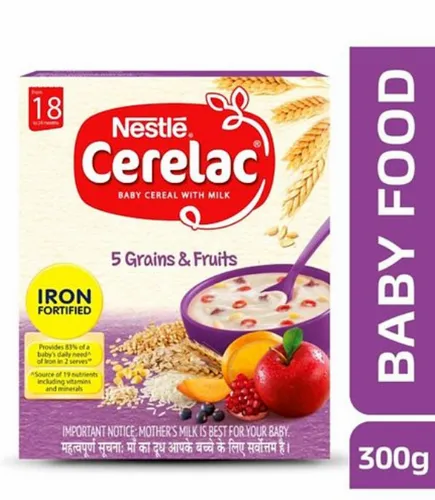

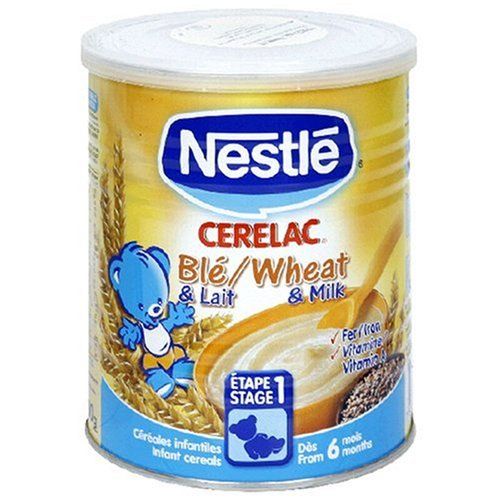

The Swiss concern continues to focus on the nutrition of premature babies and children with special medical conditions. And yet, in recent years, he has consistently increased investment in research and development in order to obtain new products for the nutrition of children after the age of six months of life, that is, for a particularly difficult period when breast milk alone is no longer enough to meet the nutritional needs of a child. , and a complete transition to artificial food has not yet taken place.

Artificial demand or valuable nutritional supplement?

Nestlé baby food has a direct impact on the health of millions of children around the world. More than 150 years have passed since Henri Nestlé (1814-1890) invented Farine Lactée, a baby porridge to support malnourished children. Today, Nestlé is the world's largest infant formula company. It has a fifth market share, followed by Danone in second place.

Today, Nestlé is the world's largest infant formula company. It has a fifth market share, followed by Danone in second place.

In recent years there has been a real boom in breastfeeding around the world. The profits of infant formula companies have fallen. Therefore, today these companies rely on "older babies" and on related products. According to EuromonitorExternal link , in 2018, the largest growth in sales in the infant formula segment was provided by specially formulated nutrition for children who have just switched from breastfeeding to artificial food.

External content Today in supermarkets in almost every country in the world you can find the widest range of types of milk powder, dairy product concentrates and breast milk substitutes for children under one year old. It would seem great, but not everyone is satisfied with these products. Activists such as Patti Rundall are sounding the alarm. Since the 1980s, she has served as Director of Strategic Policy for Baby Milk ActionExternal link , an international network of baby food organizations. Since her filing, the world has experienced a number of very large litigations in connection with the production and sale of artificial nutrition from Nestlé Corporation.

Since her filing, the world has experienced a number of very large litigations in connection with the production and sale of artificial nutrition from Nestlé Corporation.

Show more

What's the problem? It turns out that, according to her, the Nestlé and Danone concerns are the main initiators of the promotion of baby food for babies and milk formulas for children aged from 6 months to 3 years and further up to the age of nine. They use the same or very similar symbols (logos) as on infant formula, so parents, when they see the brand name, believe that they have a whole product line in front of them. However, new formulas for infant formula are just a marketing ploy.

“There is nothing new in them, so all milk formulas, starting with formulas “6 months+”, as well as formulas for children from 1 year to 3 years and older, are simply not needed, they are just a way to get more money out of parents’ pockets ”, P. Randall told swissinfo. ch. “This product should be removed from the market. But the market has become so huge that no one wants to do it, although everyone knows that they are dealing with violations of the provisions of the WHO Guidelines to stop inappropriate forms of promotion of foods for infants and young children.

ch. “This product should be removed from the market. But the market has become so huge that no one wants to do it, although everyone knows that they are dealing with violations of the provisions of the WHO Guidelines to stop inappropriate forms of promotion of foods for infants and young children.

More precisely, we are talking about the International Code on the Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, adopted by WHO in 1981. This document sets standards for ethically responsible marketing, including restrictions on advertising, sponsorship, and giving away free samples of infant formula. The default document proceeds from the fact that, anyway, only breastfeeding is the ideal nutrition for a healthy baby up to six months, which, in fact, Danone, Nestlé and their opponents agree with.

Pressure from the baby food industry

Controversy arises at the gray zone stage, when complementary foods with other foods and drinks can be introduced at about six months of age and older. You can enter, but is it necessary? And this is where the problem lies. Don't concerns create artificial demand, beneficial primarily to themselves? It is really difficult to understand this, the information received by parents from baby food manufacturers, doctors and staunch opponents of factory baby food is often contradictory.

You can enter, but is it necessary? And this is where the problem lies. Don't concerns create artificial demand, beneficial primarily to themselves? It is really difficult to understand this, the information received by parents from baby food manufacturers, doctors and staunch opponents of factory baby food is often contradictory.

Some scientific studies state that so-called “Third level milk formulas” for children aged one to three years are not needed, but they can help compensate for nutritional deficiencies, especially in cases of malnutrition or lack of certain nutrients substances in local foods”. So what's wrong with giving kids a better chance at delicious and most importantly healthy food?

Show more

Criticism of Nestlé has a long history. About forty years ago, breastfeeding activists first vociferously accused Nestlé of using an aggressive marketing strategy that resulted in mothers declining to breastfeed in favor of infant formula. The ensuing widespread boycott of Nestlé products led to major changes in the formation of marketing strategies.

The ensuing widespread boycott of Nestlé products led to major changes in the formation of marketing strategies.

However, Catherine Watt of the Geneva group La Leche LeagueExternal link , an international public private secular organization to support breastfeeding mothers, says that many women today stop breastfeeding earlier than they should. Why? “This is happening as a result of veiled pressure from the baby food industry, which has an arsenal of advertising in favor of various types of complementary foods and infant formula,” she said. “If there are doubts about whether the baby has enough breast milk, and there is some kind of milk formula in the closet, you just try to use it. And now you are already “under the hood” of the industry.”

Show more

In developing countries, the consequences of such a move can be most dramatic. CTO of the Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India BPNIExternal link JP Dadhich is particularly concerned about the high cost of these products, their negative environmental impact and potential risks of infection.

“We can't be sure about the quality of the water that these formulas are based on, which increases the risk of diarrhea. And this is in conditions when there is now enough milk of animal origin in India. After boiling, it is completely safe, in addition, it is quite acceptable here, taking into account the cultural traditions of the country. For children, it is better to use complementary foods from quality local products, continuing to breastfeed the child after 6 months.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) is also concerned that infant formula designed specifically for babies after one year of age can shorten the duration of breastfeeding by depriving the baby of important nutrients, especially if the products are labeled similarly and are promoted as more healthy alternative to breastfeeding due to the increased content of vitamins and minerals.

The devil is in the details

All this has caused and continues to cause heated debate between governments and food company lobbyists. “One of the challenges with regard to 'level 2' formula (after 6 months) is the need to understand whether foods for children aged 1 to 3 years should be considered specifically as 'substitutes' for breast milk, and if not, what should they be called.” Tom Heilandt of the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an international food standards group, tells us this.

“One of the challenges with regard to 'level 2' formula (after 6 months) is the need to understand whether foods for children aged 1 to 3 years should be considered specifically as 'substitutes' for breast milk, and if not, what should they be called.” Tom Heilandt of the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an international food standards group, tells us this.

Some governments would like to ban these formulas so as not to completely "kill" the motivation to breastfeed, while other countries want to leave the choice to consumers. India is a country with some of the most stringent regulations. Here, any products intended specifically for children under the age of two years are categorized as breast milk substitutes and thus fall under the international “Code of Regulations” of WHO. Group NestléExternal link says it has gone further than many other players in the industry by operating under European Union rules coming into effect in 2020.

Show more

At the same time, Nestlé opposes any additional regulation, arguing, based on studies already conducted in many countries, that any artificial nutrition alternative will still be less healthy than any mixture. “There is no point in restricting nutrition advertising for children under the age of one, especially when there are almost no restrictions on advertising Coca-Cola and other fast food anywhere,” says T. Filardo.

“There is no point in restricting nutrition advertising for children under the age of one, especially when there are almost no restrictions on advertising Coca-Cola and other fast food anywhere,” says T. Filardo.

Always guilty?

Nestlé recognizes that it needs to proceed with caution given its history of high-profile scandals. “It’s not for you to sell chocolate, we have a huge responsibility. Every year we produce formula for 15 million children, which is equal to the population of the Netherlands,” says T. Filardo. At the same time, the company has already updated its marketing policy several times by creating a system for reporting violations and annually providing reports on compliance with its obligations.

Unlike the pre-1980s era, the company is very clear that "breastfeeding is the best feeding option." At the same time, she wants her food products for children to be almost in no way inferior in quality to breast milk. Critics say it's not enough to be "the lesser of the evils. " However, Nestlé argues that if the company is forced out of the baby food market, companies with more than a dubious reputation will take its place. This is especially true in countries with weak regulatory environments such as China, Russia, and the United States.

" However, Nestlé argues that if the company is forced out of the baby food market, companies with more than a dubious reputation will take its place. This is especially true in countries with weak regulatory environments such as China, Russia, and the United States.

According to WHO, 58 countries around the world still do not have laws restricting the marketing of infant formula for children under one year of age. “I want to complete the story of Nestlé as a company that allegedly kills children,” says T. Filardo. “Let's move on without forgetting the past. We have drawn conclusions, we have changed. I want to look to the future, I don’t want to bear the stigma of the eternal guilty anymore, especially since someone, and our company, has done more in this area than many other companies.”

Show more

In accordance with JTI

standardsShow more: JTI certificate for SWI swissinfo.ch

Show more

Memories of the Nestlé infant formula scandal that rocked the 1970s

However, faced with a declining population in the Western world in the 1960s, sales of formula fell. Infant formula companies had to find a new market for their product. Some companies, such as Nestlé, have reached out to developing countries by providing mothers with promotional materials and samples to teach them the new method of feeding their babies.

Infant formula companies had to find a new market for their product. Some companies, such as Nestlé, have reached out to developing countries by providing mothers with promotional materials and samples to teach them the new method of feeding their babies.

However, Nestlé infant formula has had a terrible impact on Africa, South America and South Asia. The number of lives lost associated with Nestlé infant formula skyrocketed, leading to a boycott of the Nestlé company in the 1970s. The boycott did not end the problem, but rather spurred the call for international standards for infant formula.

An even more recent "water scandal" in Africa is reminiscent of the Nestlé infant formula predicament. Both of these stories prove that corporate interests, namely making money, often win over elementary human concern.

Nestlé sued the publisher for claiming "Nestlé kills babies" and won

The first noteworthy article on Nestlé's methods of distributing infant formula in third world countries was published in the New Internationalist in 1973 year under the title "Children are business". The article accused Nestlé of three things when it came to their business practices in third world countries:

The article accused Nestlé of three things when it came to their business practices in third world countries:

“Creating a need where there was none.

Convince the consumer that our product is indispensable.

Associate a product with the most desirable and unattainable concepts - and then provide a sample.

The 1974 British edition of The Baby Killer pamphlet was another tool that sparked the worldwide debate about infant formula. When a German publisher translated the booklet, changing the title to Nestlé Kills Children, Nestlé sued for defamation. The parties spent two years in litigation, and in the end Nestlé won the lawsuit. However, the judge convinced Nestlé to adjust the advertising and publications.

Nestlé saleswoman dressed as a nurse told mothers about the benefits of infant formula

When Nestlé and other dairy companies began to introduce their products to developing countries, they launched a full-scale campaign by dressing their representatives in nurse uniforms and sending them to lure customers .

These so-called "milk nannies" visited homes and hospitals to talk about their innovative formulas, and while some of them may have been educated, most of them were not. They spent time in maternity hospitals giving advice on nutrition and feeding, as well as giving mothers instructions on how to prepare infant formula.

In Singapore, milk nannies were so widespread that they were banned from visiting hospitals. As a result, these nannies simply waited outside for the new mothers to come out and then provided samples of infant formula.

In Jamaica, milk nannies could get the names of new mothers and visit their homes. In the Philippines, milk nannies visited government housing, finding homes with newborns and young children by diapers hanging from clotheslines.

Mothers reduced the nutritional value of infant formula by diluting it with water

When mothers became dependent on infant formula, the cost of the product became a problem. As a result, many women have begun to dilute the mixture so that it lasts longer. They added three times the recommended amount of water, which seriously reduced the nutritional value of the mixture.

As a result, many women have begun to dilute the mixture so that it lasts longer. They added three times the recommended amount of water, which seriously reduced the nutritional value of the mixture.

When researchers in Indonesia studied this phenomenon, they found that "only one in four women diluted the mixture close enough to the recommended concentration." At a meeting of the Health and Research Committee held in the United States on 19In 1978, Dr. Alan Jackson testified that mothers "stretched" cans of formula, which should have lasted three days for one child, up to two weeks while feeding two children the contents of one can.

Babies in developing countries made sick by contaminated water

Mothers in developing countries used water containing faecal organisms, among other contaminants, when mixing formula. When a Peruvian nurse named Fatima Patel testified before a U.S. subcommittee at 1978, she shared how difficult it would be to find clean water for infant formula:

"The river is used as a laundry, as a bathroom, as a toilet and as a source of drinking water . .. also we can say ... to get fuel for boiling of this water, the woman must go into the jungle, cut down the trunk of a tree with a machete ... and bring it on her back. No mother would use this hard-earned piece of wood to boil water. Thus, babies drink contaminated water."

.. also we can say ... to get fuel for boiling of this water, the woman must go into the jungle, cut down the trunk of a tree with a machete ... and bring it on her back. No mother would use this hard-earned piece of wood to boil water. Thus, babies drink contaminated water."

In addition, the bottles used for formula have not been sterilized. Despite labels on formula jars and instructions from milk nannies, women often lacked heating methods sufficient to sterilize bottles - alternatively, a few people could only access one pot, resulting in insufficient resources to properly sterilize a bottle. .

Nestlé attracted mothers and babies with free samples

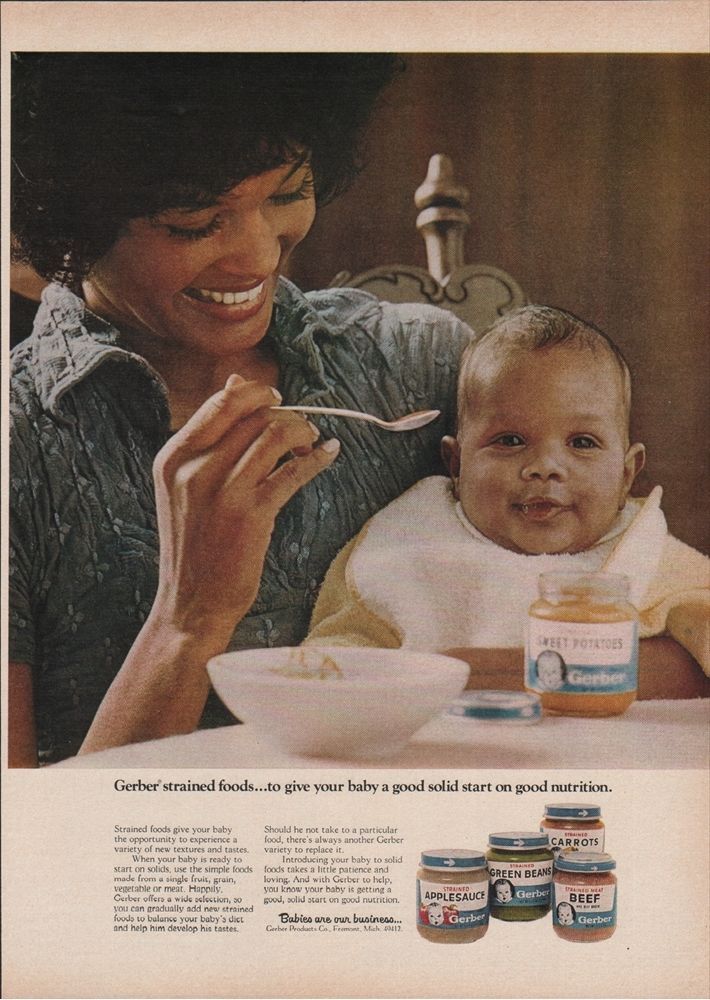

Nurses distributed free samples of formula to new mothers, giving them the option to either stop breastfeeding or use formula in combination with breastfeeding.

However, when the baby is breastfed less or stops suckling, the mother's milk gradually dries up. This led to an inevitable dependence on formula milk.

Although financial dependence was significant, equally important was the lack of nutrients and antibodies that infants received from breast milk. Scientists have recognized the importance of colostrum, a milk-like substance produced by a mother shortly after a baby is born, in building a baby's immune system. As infants began to breastfeed less, the overall health of infants in third world countries began to deteriorate.

WHO and UNICEF linked infant mortality to infant formula started collecting data.

They found that millions of babies were dying from malnutrition and diarrhea caused by diseases such as kwashiorkor (a type of severe malnutrition) and alimentary insanity (alimentary dystrophy) caused by protein deficiency. Doctors have linked these ailments to the increased use of infant formula. Due to the growing reliance on infant formula, babies' immune systems were less able to develop, fight disease, and allow the baby to survive infancy.

Doctors have even coined the term "weaning diarrhea", defined as "a collection of illnesses in an infant described as a weaning syndrome". This is due to the introduction of other foods and the loss of the protective properties obtained with breast milk.

This is due to the introduction of other foods and the loss of the protective properties obtained with breast milk.

Formula companies made mothers question their own ability to care

Formula companies used the so-called "confidence trick" to tell mothers that they should be aware of the possibility of their babies being malnourished. This tactic will create fear or anxiety in mothers and make them question their ability to produce enough breast milk for their babies and encourage mothers to start using formula as an alternative. As a result, their breast milk gradually dried up.

Mothers in developing countries, especially in the 60s and 70s, had little doubt about their ability to breastfeed until they had an alternative. As soon as the mother stopped breastfeeding, even temporarily, she was forced to feed her baby with formula milk.

As the pamphlet Baby Killer puts it, "Somehow mothers decide that a bottle is necessary for the milk she gives . .. some mothers may even be so concerned about not having enough milk that they won't have any." .

.. some mothers may even be so concerned about not having enough milk that they won't have any." .

Western culture bombarded women with marketing in the 1970s

Another key element in the transition from breastfeeding to formula feeding in developing countries was advertising from Nestlé and other formula manufacturers. Many women moved to the cities in the 1970s, where they were bombarded with messages, both overt and covert, that bottle-feeding was both modern and "Western."

Both print and broadcast media in developing countries such as Brazil "where infant formula was the most advertised product after cigarettes and soap ... promised, albeit subtly, that formula was a modern method of infant feeding associated with mobility, and that she would produce plump-cheeked children."

Companies bribed clinics and hospitals with free food and financial incentives

In many developing countries, Nestlé and other dairy companies supplied clinics and hospitals with large amounts of formula every year. This encouraged institutions to pass on the formula to their patients, but also attracted the medical community to the corporate plan.

This encouraged institutions to pass on the formula to their patients, but also attracted the medical community to the corporate plan.

In Nigeria, clinics received up to "8,000 free cans of infant formula annually." In Ethiopia, India and other parts of the world, companies have also given free bottles and other gifts to clinics and hospitals to encourage breastfeeding. Still later, formula companies began donating large sums to hospitals and physicians, with the companies spending "untold millions of dollars to subsidize office furniture, research projects, gifts, conferences, publications, and medical professional travel."

Infant formula companies set standards in formula in the early 1980s

In 1980, the World Health Assembly adopted WHO and UNICEF recommendations on international infant feeding practices. Although they released an official code the following year, Nestlé and three other companies publicly stated their unwillingness to follow any official policy.

In the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes adopted by the World Health Assembly at 1981, stated that baby food companies should not have direct contact with mothers, hospitals or health care workers - especially with gifts - they should not provide misleading information and their product labels should be clear and contain appropriate warnings. Companies also had to explain the costs of using mixtures. Countries around the world began to adopt the Code, and companies soon agreed. In the end, Nestlé agreed to follow the Code at 1984 year. However, this policy has hardly been enforced and companies continue to break and break the rules.

The worldwide boycott of Nestlé began in 1977 and continued until 1984.

In the 1970s, the personal is political movement brought new attention to breastfeeding on a global scale. The 1970s saw increased concern about women and babies in Third World countries, where breastfeeding had declined significantly over the previous decade.

Researchers studied this and the associated rise in bottle feeding, eventually finding that not only did misuse of infant formula lead to infant illness and death, and that mothers were being misled about the effectiveness of formula. The study resulted in a boycott of Nestlé, which had "81 factories in 27 developing countries and 728 sales centers in all parts of the world promoting their products."

In the United States the Infant Formula Action Coalition announced a boycott that quickly spread to parts of Europe, Canada and Australia. Between 1977 and 1981, the Nestlé company tried to solve problems and restore its image; meanwhile, the International Infant Food Surveillance Network (IBFAN), a group of six anti-Nestlé organizations, formed and fought to oversee the infant formula industry.

Although International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was adopted in 1981, Nestlé did not agree to follow it until 1984. This boycott ended.

This boycott ended.

The boycott resumed in the late 1980s and continues to this day

The Nestlé boycott was renewed in 1988. Since then, more than 20 countries have boycotted Nestlé's subsidiaries due to their persistent attempts to circumvent International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes . The non-profit organization Baby Milk Action insists that the boycott will continue until Nestlé agrees to follow their four-point action plan.

Nestlé has a policy of its own but continues to face allegations of selling "low-quality" infant formula in South Africa. In February 2018, Nestlé was accused of not including important ingredients in its product in South Africa, as well as of "a strategy to increase profits by trying to convince parents to buy more expensive products, believing that they are better for their child's health."

Nestlé also caused Fanta Syndrome

Infant formula is not the only product that major Western companies have introduced in less developed countries that has had detrimental health effects.