Should i feed my baby if he is vomiting

Baby Vomiting

During your baby’s first year of life, there’s likely to be one or two curve balls thrown in your direction. Feeding your baby can be an enjoyable way to help your baby’s development, but it can also come with its fair share of questions, worries and surprises.

As strange as it is to watch your baby projectile vomit across a room (it happens), baby vomiting is a common occurrence. However, it raises a lot of questions. Questions like, why do babies vomit? Why is my baby vomiting after feeding? and should I feed my baby after vomiting?

Here we’re providing the answers to those questions, to help you stay calm and in control when it comes to feeding your baby.

Baby spit up vs baby vomit - what’s the difference?

Baby posseting/spit up

In the first few days or weeks of life, your baby might bring up small amounts of milk during a feed. This is commonly known as posseting or spit up1. It’s usually nothing to worry about, and can happen whether your baby is breast or formula fed.

When your baby spits up, it could be due to a cough, or because they’ve been crying. It’s also possible that your baby has indigestion or reflux. Whatever the cause, rest assured that it tends to settle down as your baby’s gut matures2.

Reflux is very similar to posseting and happens because the muscles at the top of your baby’s food pipe (oesophagus) aren’t yet fully developed, so milk is able to come back up again.

Ultimately, the experience tends to be worse for parents, with your baby being completely unphased!

Baby vomiting

Whilst spit up usually flows from your baby’s mouth during or after a feed, baby vomiting happens with some amount of force3. Vomiting is a very common, often non-specific, but distressing symptom for both babies and parents. It’s advisable to seek medical advice if your baby is vomiting milk consistently, even if they have no fever, as it's possible that another issue may be at play.

Baby vomiting after feeding, why does it happen?

There are lots of reasons why babies vomit, the vast majority of which are easily managed.

Gastroenteritis

A common cause of vomiting is gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. You’ll typically hear it referred to as a tummy bug or food poisoning. The most common cause of gastroenteritis is rotavirus4, but there are other viruses and bacteria that could also be the cause, such as E. Coli and salmonella.

Whilst unpleasant, tummy bugs usually resolve themselves within a week, and there are some simple steps you can take to prevent them occurring in the first place. For example, if you’re bottle feeding either breast or formula milk, it’s recommended that you fully sterilise all of your baby’s feeding equipment5 before and after each and every feed.

If you’re weaning your baby, make sure that all food is prepared by paying attention to basic hygiene measures such as clean hands, equipment, and surfaces6, as well as ensuring food is cooked thoroughly.

Dehydration in babies

If your baby’s been suffering with a tummy bug, it’s worth keeping an eye out for symptoms of dehydration which include8:

- A dry mouth, fewer tears and fewer wet nappies.

- Dark yellow urine.

- Drowsiness.

- A sunken fontanelle (the soft spot on the top of your baby’s head).

- Blotchy and cold feet and hands.

Prevention is better than the cure, so if your baby has been ill, make sure that you give them plenty of liquids in the form of their usual milk, be it breast milk or formula milk .

Some dehydration do’s and don’ts

It may take a little while for your baby to get back to drinking the amount of milk they’re used to after a tummy bug. To help them keep their milk down, give them small sips, around five mls, every five minutes - little and often is the key.

If you find that your baby is struggling to manage even small amounts of milk, it’s best to speak with your GP who’ll give your baby a thorough check and may prescribe oral rehydration salts, and paracetamol or ibuprofen if they’re in pain.

Whilst it might be tempting to top up your baby’s fluid intake to help them get over a tummy bug, never dilute breast or formula milk with water, or give your baby fruit juices or other non-milk drinks.

Allergies and intolerances

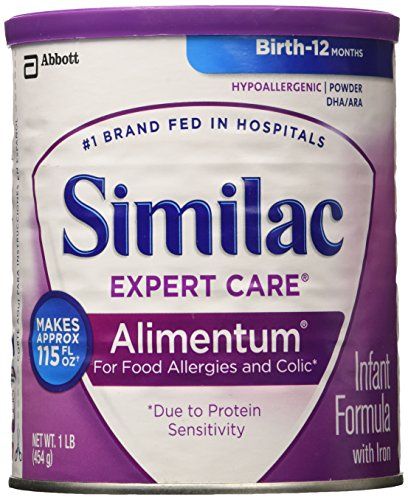

In some cases, baby vomiting can signal an allergy or intolerance to cow’s milk, and if you suspect that this might be the case, it’s best to talk your baby’s symptoms through with your GP.

Pyloric Stenosis

Whilst baby projectile vomit can happen as a one off, if it’s happening on a regular basis then it’s possible that they have a condition known as pyloric stenosis.

It’s caused by a narrowing of the opening between the stomach and the small bowel9 and means that milk is unable to get to the gut in order to be digested. Instead, undigested milk builds up and eventually causes your baby to projectile vomit.

If your baby has pyloric stenosis, it’s likely to be picked up early and treated immediately with surgery. As a condition, it’s uncommon, but if you have any concerns, always discuss them with your GP.

My baby is vomiting curdled milk, should I be worried?

A baby vomiting curdled milk can feel (not to mention look and smell) unsettling. It can occur in either breast or formula fed babies, and is usually the result of milk being mixed with stomach acid, causing it to curdle10.

It can occur in either breast or formula fed babies, and is usually the result of milk being mixed with stomach acid, causing it to curdle10.

It’s important to remember that your baby spitting up curdled milk is not usually a cause for concern, but always keep an eye out for any changes to your child’s feeding or spit up habits.

Should I feed my baby after vomiting?

If your baby’s been vomiting, it’s possible that they’ll feel a little hungry and dehydrated. As such, you should continue feeding your baby their usual breast or formula milk feeds11. Once the vomiting has stopped, offer your baby a feed. Start with small amounts and if they’re comfortable, follow their lead and let them take what they need.

How to avoid baby vomiting after feeding

Baby vomit is part of the course when it comes to parenting, but there are things you can do to limit the amount of muslin cloths you find yourself going through on a daily basis. For example12:

For example12:

- Let gravity do its thing and hold your baby upright during a feed and for as long as possible afterwards.

- Try carrying your baby in a sling to keep them upright.

- If your baby is formula fed, give them smaller feeds, more often.

- Make sure that your baby is laid on their back to sleep.

Avoid raising the head of the cot or changing your diet if you’re breastfeeding, and instead speak to your health visitor or GP to get the advice and guidance that you need.

When should I seek help?

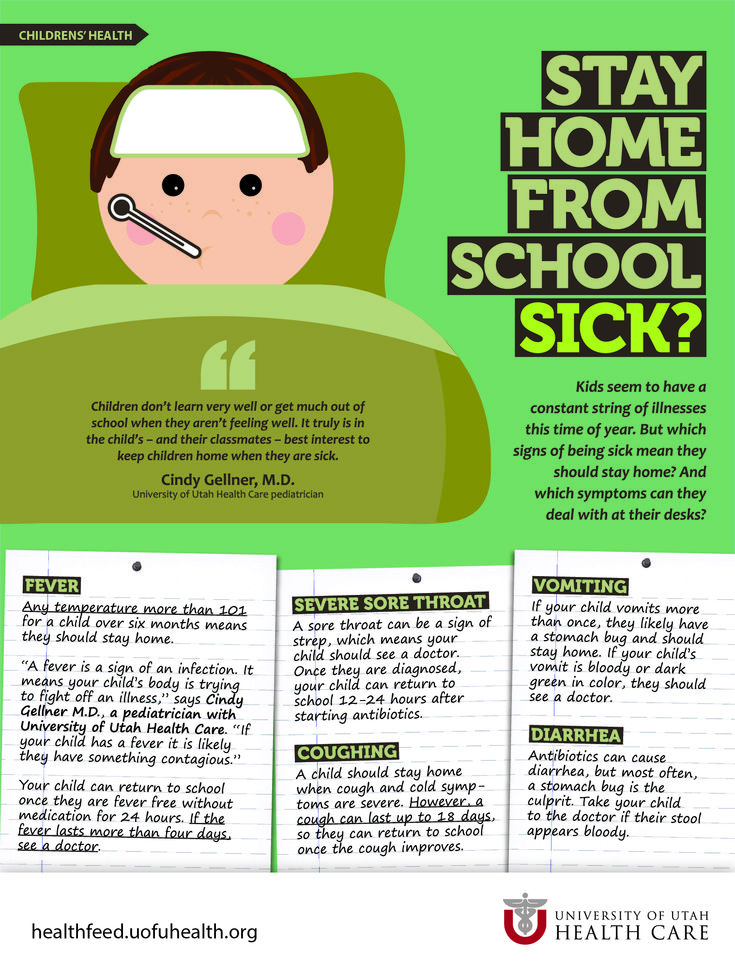

Chances are there’s nothing to worry about your baby vomit as it is very common when it comes to babies. However, you should always get medical help and advice if your baby13:

- Isn’t gaining weight.

- Is consistently vomiting large amounts of milk.

- Starts to vomit bile or yellow liquid.

- Projectile vomits within 30 minutes of feeding.

Is at risk of becoming severely dehydrated.

Here at Aptaclub, our aim is to provide you with the information you need to embrace your baby’s growth and development, as well as the possible solutions to common issues that you might find yourself dealing with.

Dr Punam Krishan

Dr Punam Krishan is an NHS GP and media doctor with a specialist interest in public health, family and lifestyle medicine. She is also a honorary senior clinical lecturer at the University of Glasgow. Alongside this, Punam is a writer and director of the British Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

Read more

References

- National Childbirth Trust (NCT). What is baby reflux? [online] 2019. Available at https://www.nct.org.uk/baby-toddler/feeding/common-concerns/what-baby-reflux-symptoms-and-support. Accessed March 2021.

- National Health Service (NHS). Reflux in babies [online] 2019. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/reflux-in-babies/. Accessed March 2021.

- Mayo Clinic.

Spitting up in babies: What’s normal and what’s not [online] 2021. Available at https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/healthy-baby/art-20044329#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20difference%20between,than%20dribbling%20from%20the%20mouth. Accessed April 2021.

Spitting up in babies: What’s normal and what’s not [online] 2021. Available at https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/healthy-baby/art-20044329#:~:text=What%20is%20the%20difference%20between,than%20dribbling%20from%20the%20mouth. Accessed April 2021. - National Health Service (NHS). Rotavirus vaccine overview [online] 2020. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/rotavirus-vaccine/. Accessed March 2021

- National Health Service (NHS). Sterilising baby bottles [online] 2019. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/baby/breastfeeding-and-bottle-feeding/bottle-feeding/sterilising-baby-bottles/#:~:text=It%27s%20important%20to%20sterilise%20all,in%20particular%20diarrhoea%20and%20vomiting.&text=You%20can%20also%20turn%20teats,them%20in%20hot%20soapy%20water. Accessed March 2021.

- National Health Service (NHS) Start 4 life [online]. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/start4life/weaning/safe-weaning/. Accessed March 2021.

- National Health Service (NHS). What should I do if I think my baby is allergic or intolerant to cow’s milk? [online] 2019. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/childrens-health/what-should-i-do-if-i-think-my-baby-is-allergic-or-intolerant-to-cows-milk/. Accessed March 2021.

- National Health Service (NHS). Dehydration [online] 2019. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dehydration/. Accessed March 2021.

- Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) NHS Foundation Trust. Pyloric Stenosis [online]. Available at https://www.gosh.nhs.uk/conditions-and-treatments/conditions-we-treat/pyloric-stenosis/. Accessed March 2021.

- National Health Service (NHS). Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust. Pyloric Stenosis [online]. Available at https://www.gosh.nhs.uk/conditions-and-treatments/conditions-we-treat/pyloric-stenosis/. Accessed March 2021.

- National Institute for Care and Excellence (NICE). Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis in under 5s: diagnosis and management [online] 2009.

Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/chapter/1-Guidance#nutritional-management. Accessed April 2021.

Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg84/chapter/1-Guidance#nutritional-management. Accessed April 2021. - National Health Service (NHS). reflux in babies [online] 2019. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/reflux-in-babies/. Accessed March 2021.

- National Health Service (NHS). Diarrhoea and vomiting [online] 2020. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/diarrhoea-and-vomiting/. Accessed March 2021.

Last reviewed: 09th June 2021

Reviewed by Oriana Hernandez Carrion

Brighter futures start here

Discover more about infant development to help shape your baby's future

Join now for free

Related articles

- Aptaclub home

- Baby

- Diet and nutrition

- Feeding problems

- Baby Vomiting

How to Know Whether You Should

Your baby just threw up all the milk they’ve chugged down so far, and you’re wondering if it’s OK to continue feeding. How soon should you feed your baby after vomiting?

How soon should you feed your baby after vomiting?

It’s a good question — just about every parent has likely pondered this. Spit-up is almost a rite of passage for babies (and parents). Baby vomiting is also common and can happen for many reasons. Most of the causes aren’t serious.

The short answer — because you may have a very fussy baby on your hands and want to get back to them ASAP — is yes, you can usually feed your baby after they vomit all over your favorite sweater, sofa throw, and rug.

Here’s just about everything you need to know about feeding your baby after vomiting.

Baby vomit and spit-up are two different things — and they can have different causes. Spitting up is common in babies under the age of 1 year. It typically happens after feeding. Spit-up is usually an easy flow of milk and saliva that dribbles from your baby’s mouth. It often happens with a burp.

Spit-up is normal in healthy babies. It can happen for several reasons. About half of all babies 3 months and under have a type of acid reflux called infant reflux.

Spit-up from infant reflux is especially bound to happen if your baby has a full stomach. Being careful not to overfeed a bottle-fed infant can help. Spitting up typically stops by the time your baby is a year old.

On the other hand, vomiting is typically a more forceful throwing-up of milk (or food, if your baby is old enough to eat solids). It happens when the brain signals the muscles around the stomach to squeeze.

Vomiting (like gagging) is a reflex action that can be triggered by a number of things. These include:

- irritation from a viral or bacterial infection, like the stomach bug

- fever

- pain, such as from a fever, earache, or vaccination

- blockage in the stomach or intestines

- chemicals in the blood, like medicine

- allergens, including pollen; very uncommon in babies under 1 year

- motion sickness, such as during a car ride

- dizziness, which might happen after being twirled around too much

- being upset or stressed

- strong smells

- milk intolerance

Vomiting is also common in healthy babies, but it might mean that your baby has caught a bug or is feeling a bit under the weather.

Too much vomiting can cause dehydration and even weight loss in very serious cases. Milk feeding can help prevent both of these. Offer your baby a feeding after they’ve stopped throwing up. If your baby is hungry and takes to the bottle or breast after vomiting, go right ahead and feed them.

Liquid feeding after vomiting can sometimes even help settle your baby’s nausea. Start with small amounts of milk and wait to see if they vomit again. Your baby might vomit the milk right back up, but it’s better to try than not.

If your little one is at least 6 months old and doesn’t want to feed after throwing up several times, offer them water in a bottle or a spoon. This can help prevent dehydration. Wait a short while and try feeding your baby again.

In some cases, it’s better not to feed a baby right after vomiting. If your baby is throwing up because of an earache or fever, they may benefit from medication first.

Most pediatricians recommend pain medications like infant Tylenol for babies in their first year. Ask your doctor about the best medication and dosage for your baby.

Ask your doctor about the best medication and dosage for your baby.

If giving pain medication based on your doctor’s advice, wait about 30 to 60 minutes after doing so to feed your little one. Feeding them too soon might cause another bout of vomiting before the meds can work.

Motion sickness isn’t common in babies under the age of 2 years, but some babies may be more sensitive to it. If your baby vomits from motion sickness, it’s better not to offer a feeding afterward.

You’re in luck if your baby likes to nod off in the car. Wait until you’re out of the car to feed your baby milk.

Baby vomiting can be worrying, but it usually goes away by itself — even if your baby has the stomach bug. Most babies with gastroenteritis don’t need medical treatment. This means that most of the time, you’ll have to bravely wait out your baby’s vomiting.

But sometimes, throwing up is a sign that something’s not right. You know your baby best. Trust your gut and call their doctor if you feel your little one is unwell.

In addition, take your baby to a doctor immediately if they’ve been vomiting for 12 hours or longer. Babies and children can dehydrate quickly from too much vomiting.

Also call your baby’s pediatrician if your baby can’t hold anything down and has signs and symptoms of being unwell. These include:

- constant crying

- pain or discomfort

- refusal to feed or drink water

- diaper that hasn’t been wet for 6 hours or longer

- diarrhea

- dry lips and mouth

- crying without tears

- extra sleepiness

- floppiness

- vomiting blood or fluid with black flecks (“coffee grounds”)

- lack of smile or response

- vomiting green fluid

- bloated tummy

- blood in bowel movements

You won’t usually have any control over when or how much your baby vomits. When it happens on occasion, repeat this mantra to help you cope: “Healthy babies sometimes vomit.”

However, if your baby often vomits (or spits up) after feeding, you may be able to take some preventative steps. Try these tips:

Try these tips:

- avoid overfeeding

- give your baby smaller, more frequent feeds

- burp your baby often between feeds and after feeds

- prop up your baby so they’re upright for at least 30 minutes after feeding (but don’t prop your baby up for sleep or use anything to position them in their crib or elevate their mattress)

If your baby has a tummy bug and is old enough to eat solid foods, avoid feeding solids for about 24 hours. A liquid diet can help the stomach settle after a bout of vomiting.

Vomiting and spit-up are common in healthy babies. In most cases, you can milk feed shortly after your baby vomits. This helps to prevent your baby from getting dehydrated.

In some cases it’s best to wait a little while before trying to feed your baby again. If you’re giving your child medication like pain and fever relievers, wait a bit so the meds don’t come back up.

If your baby is vomiting a lot or seems otherwise unwell, call your pediatrician immediately. If you’re unsure if your baby’s vomiting or spit-up is cause for concern, it’s always best to check with your doctor.

If you’re unsure if your baby’s vomiting or spit-up is cause for concern, it’s always best to check with your doctor.

Vomiting and loose stools in a child

Ambulance for children: +7 (812) 327-13-13

In a child (especially in the first year of life), the digestive system is very sensitive not only to the quality of food and its compliance with age, but also to any drastic changes in diet. Naturally, having received something unacceptable or unusual, the body seeks to get rid of it as soon as possible, either by regurgitating the contents of the stomach through the mouth (vomiting), or by dramatically accelerating the passage of uncomfortable food through the intestines (diarrhea). However, nutritional errors, like food poisoning, are not actually the most common causes of vomiting and/or loose stools in children - most intestinal disorders in babies are associated with intestinal infections (bacterial or viral).

Of course, careful personal hygiene reduces the risk of intestinal infections, but there are no methods that guarantee 100% protection against them for your baby - a child lives in an unsterile world inhabited by pathogens, many of which can be transmitted not only by contact, but also by air - by drip. Therefore, it is not worth conducting an investigation to find out which of the family members infected the child - all claims are against the one who created the microbes.

Therefore, it is not worth conducting an investigation to find out which of the family members infected the child - all claims are against the one who created the microbes.

In the event of vomiting and loose stools, a doctor's consultation is absolutely essential. This is especially true of vomiting - this symptom can be a sign of a number of serious diseases that have nothing to do with the gastrointestinal tract. If vomiting is combined with a headache or appeared after a head injury, call an ambulance without waiting for the visit of the local doctor. Save the last few stools until the doctor arrives by sealing the diaper or panties in a plastic bag - most likely the doctor will want to examine them.

Naturally, with vomiting and diarrhea, the main function of the digestive system, the absorption of nutrients, is disrupted. However, if a child’s body can tolerate a nutritional deficiency for quite a long time without serious consequences, then a lack of fluid and salt (the so-called dehydration or dehydration caused by vomiting or loose stools) can dramatically worsen the child’s condition and cause serious complications. Therefore, the first therapeutic measures for vomiting and diarrhea are hunger and drink.

Therefore, the first therapeutic measures for vomiting and diarrhea are hunger and drink.

Hunger

If a doctor's visit is expected in the next few hours, the baby should not be fed until the doctor arrives. In the case where urgent medical advice is not possible, you should take a break in the diet for 6-8 hours (for infants, this means skipping one feeding). In the future, the child is fed fractionally (that is, often and little by little). Breastfed babies need to be fed after two hours, while reducing the feeding time. In children of the first year of life, complementary foods should be abandoned on the first day, limiting themselves to breast milk or its substitute. Older children can be offered crackers, biscuits, rice porridge on the water. The basic principle of nutrition in this case is better not to give than to give (if the child does not ask for food, you do not need to feed him at all). Further dietary recommendations are best obtained from your doctor - as already mentioned, with the problems described, a doctor's consultation is absolutely necessary.

Drinking

It must also be fractional. A single volume of liquid for infants should not exceed 10-15 ml, for older children - 30-100 ml (large volumes, stretching the stomach wall, can provoke vomiting). It is necessary to water the child in 10-30 minutes (the smaller the one-time volume, the more often you should drink). The daily volume of fluid taken should not be less than the daily need of the child, taking into account the increased losses: for an infant, this is 800–1000 ml, for older children, up to two or three liters. Do not be afraid to overdose the liquid - here the principle is exactly the opposite: it is better to pass than not to give (meaning the daily volume, not a single serving).

Having dealt with the amount of liquid, it makes sense to discuss what should a child drink? The main drink may be water, weakly brewed tea, herbal teas (for example, chamomile or children's stomach tea). If the child is not accustomed to unsweetened drinks, it is better to use fructose for sweetening, since the sucrose contained in regular sugar activates the fermentation processes in the intestines.

However, such drinking is unable to compensate for the loss of salts (especially these losses are great with vomiting). Therefore, at least half of the daily volume of liquid should be represented by saline solutions. In this capacity, it is most convenient to use Regidron powders (they are sold at any pharmacy). The contents of the package are dissolved in one liter of water. In the absence of Regidron, you can prepare a similar solution yourself: 8 teaspoons of fructose or sugar and ⅔ teaspoon of salt per liter of water. It is also necessary to give the child saline solutions because even with a significant water deficit in the body, the baby will refuse to drink if the salt deficiency is even greater than the water deficit.

Note that in gastrointestinal disorders, the correction of water-salt disorders is the main therapeutic factor, much more important than the use of the most modern and effective drugs.

Medications

And yet, what medicines can be given to a child with diarrhea and vomiting before the doctor arrives?

At the very beginning of the disease, enterosorbents can be useful - Polysorb, Zosterin-Ultra, Polypefan, Filtrum (it is very difficult to give the child favorite activated charcoal in an effective dose). It will also help to normalize Smekta's stool - three doses a day, children over two years old - a whole sachet, young children - one sachet per day for a year of life. Before use, a sachet of Smecta should be dissolved in 50 ml of boiled water (allowed - in milk mixtures). If diarrhea or vomiting is accompanied by an increase in temperature above 38 ºС, the temperature should be reduced, since at elevated temperatures fluid losses increase to humidify the exhaled air.

It will also help to normalize Smekta's stool - three doses a day, children over two years old - a whole sachet, young children - one sachet per day for a year of life. Before use, a sachet of Smecta should be dissolved in 50 ml of boiled water (allowed - in milk mixtures). If diarrhea or vomiting is accompanied by an increase in temperature above 38 ºС, the temperature should be reduced, since at elevated temperatures fluid losses increase to humidify the exhaled air.

WHAT NOT TO DO?

First of all, do not try to wash the child's stomach - this violent event can only lead to additional loss of salts. In addition, after this unpleasant procedure, you are unlikely to be able to give the child a drink or give him the necessary medicine.

In no case should you also give your child antibiotics without a doctor's prescription. First, today antibiotics in the treatment of intestinal infections are not used so often. Secondly, they begin to act only on the second or third day of course use, so a few hours do not solve anything.

The widely advertised Imodium (synonyms - Lopedium, Loperamide) also cannot be used alone - the drug does not have a therapeutic effect on the disease that caused loose stools, it simply inhibits intestinal motility. In addition, age restrictions and possible side effects of this drug make it possible to use it in children only under the supervision of the attending physician.

Let me emphasize once again that in case of vomiting and (or) loose stools in a child, timely (that is, immediate) consultation with a doctor is absolutely necessary. Usually, the delay in going to the doctor is due to a banal reason - parents are simply afraid that the child will be “taken to the hospital”. With early treatment, these fears are completely unfounded - most cases of intestinal disorders in children proceed without any problems and can be treated at home. The need for hospitalization is more often associated not with the severe course of the disease itself (although this also happens), but with dehydration that has developed during unsuccessful attempts to cope with the disease on their own. In any case, the doctor can only offer you inpatient treatment - no one will "take" your child anywhere without your consent. And finally, today it should be borne in mind that in children, gastrointestinal upset may be the only initial manifestation of COVID 19 infection..

In any case, the doctor can only offer you inpatient treatment - no one will "take" your child anywhere without your consent. And finally, today it should be borne in mind that in children, gastrointestinal upset may be the only initial manifestation of COVID 19 infection..

Author of the article:

Kanter M.I. – pediatrician of the highest category

Vomiting and diarrhea in a child

Acute gastroenteritis is characterized by an increase in body temperature (from subfebrile condition to high fever), vomiting, liquefaction of the stool. Rotavirus is the most common cause of gastroenteritis. The most severe is the first episode of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children from 6 months to 2-3 years. The peak incidence of this infection occurs in the winter - spring.

The danger of viral gastroenteritis is associated with rapid dehydration and electrolyte disturbances due to loss of water and salts with loose stools and vomiting. Therefore, feeding the child is of fundamental importance. In order not to provoke vomiting, you need to drink fractionally (1 - 2 teaspoons), but often, if necessary, every few minutes. For convenience, you can use a syringe without a needle or a pipette. In no case should you drink the child with just water, this only exacerbates electrolyte disturbances! There are special saline solutions for drinking - rehydron (optimally ½ sachet per 1 liter of water), Humana electrolyte, etc.

In order not to provoke vomiting, you need to drink fractionally (1 - 2 teaspoons), but often, if necessary, every few minutes. For convenience, you can use a syringe without a needle or a pipette. In no case should you drink the child with just water, this only exacerbates electrolyte disturbances! There are special saline solutions for drinking - rehydron (optimally ½ sachet per 1 liter of water), Humana electrolyte, etc.

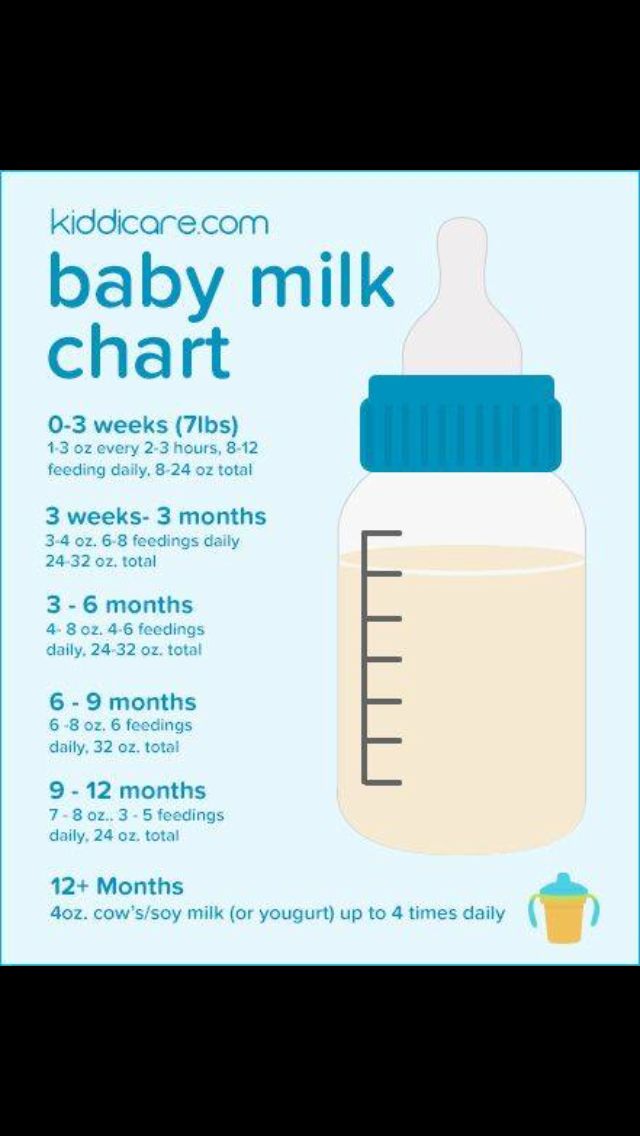

Daily need for fluid is presented in the table:

Weight of the child Daily need for liquid

2 - 10 kg 100 ml/kg

10 - 20 kg 1000 ml + 50 ml/kg per kg over 10 kg

> 20 kg 1500 ml + 20 ml/kg for each kg over 20 kg

In addition, current fluid losses with loose stools and vomiting are taken into account - for each episode of diarrhea / vomiting, an additional 100 - 200 ml of fluid is given.

Intravenous rehydration (fluid replenishment with drips) is done only for severe dehydration and persistent vomiting. In all other cases, you need to drink the child - it is safe, effective and painless.

Smecta (but do not give smecta if it induces vomiting), espumizan or Sab simplex are used as adjuvants. Enterofuril is not recommended for use, as it is not effective either in viral infections or in invasive bacterial intestinal infections. In the diet during the acute period, fresh vegetables and fruits (except bananas), sweet drinks are excluded, and whole milk is limited only in older children.

Parents need to be aware of the first signs of dehydration - a decrease in the frequency and volume of urination, thirst, dry skin and mucous membranes. With increasing dehydration, the child becomes lethargic, stops urinating, thirst disappears, the skin loses turgor, and the eyes “sink”. In this case, there is no time to waste, it is necessary to call a doctor and hospitalize the child.

The appearance of blood and mucus in the stool in a child should be alerted, because this is typical for bacterial enterocolitis. Stool with such infections is not large (in contrast to copious watery stools with rotavirus infection), false urge to defecate and abdominal pain may be noted.