Starchy baby food

Can starchy foods be harming your baby?

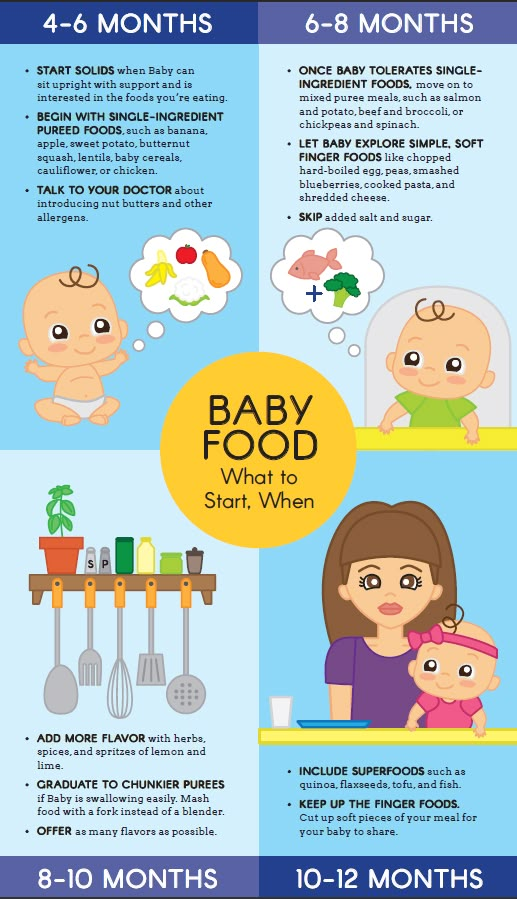

It’s now recommended to start babies on solids between 4 and 6 months. However, in conflict to our supermarket shelves adorned with baby-rice, baby-porridge and baby-muesli, science warns against feeding infants a diet rich in starchy foods (also known as farinaceous foods, e.g. rice, breads, potatoes, porridge, cereals, crackers, etc). In fact, some people believe they’re simply the worst meals to feed young babies!

Can starchy foods be harming your baby?

The science is in…

Medical science has clearly understood that the amylase enzyme ‘ptyalin’ (pronounced ty-u-lin) contained within our saliva is critical in initiating the body’s digestive processes. Pancreatic amylase, which is secreted by the pancreas into the small intestine, is also considered a workhorse in the body’s digestive process. These processes are used to break down starch into glucose sugars. What science also knows is that infants produce almost no ptyalin, and very little pancreatic amylase, until well after 6 months of age.

Without these starch-busting enzymes being produced, 3 bodily reactions commonly occur after feeding a baby starch:

- The indigestible starch ‘ferments’ in the intestinal tract, causing digestive discomfort and possibly digestive disorders

- Baby’s mucous ‘thickens’, potentially causing ear, nose or throat problems

- Your baby’s blood sugar levels increase

Perhaps this is a partial explanation for the epidemic levels of continual sore tummies, runny noses, recurring ear infections, tonsillitis, bronchiolitis, asthma and even diabetes and obesity we now see prevalent in the developed world?

Hold on, but what about babies in developing countries, or Asian babies, being fed rice and other staple starches? Why is it OK for them?

It’s a really simple answer actually. For thousands of years, mothers in these countries have always chewed the baby food first, before feeding it to their infant – unwittingly coating the baby’s food with the ptyalin enzyme from their own saliva.

Interestingly, the levels of asthma, diabetes, obesity and ear infections are on the rise in developing countries too. Could this be something to do with changes in how babies in these countries are now being fed?

But getting back to Western medicine and its history…

Apparently medical science has known that starchy foods aren’t good for infants for quite some time.

In the 1800s, renowned surgeon and obstetrician Pye Henry Chavasse wrote, “I wish, then, to call your special attention to the following facts, for they are facts – Farinaceous foods, of all kinds . . . are worse than useless – they are positively, injurious, they are, during the early period of infant life, perfectly indigestible . . . A babe’s salivary glands . . . does not secrete its proper fluid – namely, ptyalin, and consequently the starch of the farinaceous food is not converted . . . and is, therefore, perfectly indigestible and useless – nay, injurious to an infant”.

Since then there have been numerous other respected doctors, professors and scientists all saying a similar thing, over and over and over again. This includes Prospiro Sonsino, Tilden, Routh, Huxley, Youmans, Dalton, Page, Densmore, to name but a few. However, in recent decades medicine and the science of nutrition seem to have ‘forgotten’ this knowledge.

This includes Prospiro Sonsino, Tilden, Routh, Huxley, Youmans, Dalton, Page, Densmore, to name but a few. However, in recent decades medicine and the science of nutrition seem to have ‘forgotten’ this knowledge.

Dr Page wrote, “Milk is the food for babies and contains all the elements necessary to make teeth, and until they are made, it should continue to be the sole food. It is not enough that two or three or a half dozen teeth have come through, that they should be expected to do any part of a grown child’s work … Upon no consideration should any of the farinaceous or starchy articles be added until the mouth bristles with teeth”.

Then, in the early to mid-1900s, rebel health pioneer and prolific writer Dr Herbert Shelton focused on this subject too, when he wrote, “The fact that Nature makes no provisions for the digestion of starches before full dentition [growing of teeth], should be sufficient evidence that she does not intend it to form any part of the infant’s diet. Before the teeth are fully developed the saliva of the infant contains a mere trace of ptyalin, the digestive ferment or enzyme that converts starch into sugar . . . Certain it is that nature did not intend the baby to chew food until its teeth are sufficiently developed to perform this function . . . No starchy foods or cereals should be given under two years”.

Before the teeth are fully developed the saliva of the infant contains a mere trace of ptyalin, the digestive ferment or enzyme that converts starch into sugar . . . Certain it is that nature did not intend the baby to chew food until its teeth are sufficiently developed to perform this function . . . No starchy foods or cereals should be given under two years”.

So why do we feed our babies starchy food?

This is such important knowledge, I seems truly odd that with such massive scientific evidence, our society remains so obsessed with starchy baby foods – and the equally nonsensical belief that carbohydrate starches should be the main staple of all infants’ ongoing diet.

Is it a case of the ‘big food’ industry pushing unnecessary product on consumers to satisfy the never-ending desire for dividends? Are we rushing too quickly into feeding solids, and quick-and-easy food options, due to our hectic, fast paced modern lives? Have we simply forgotten what our grandparents and great-grandparents knew intuitively about feeding infants? Who knows?

In some ways it reminds me of how completely accepted cigarettes were half a century ago, when most people genuinely didn’t understand – simply because they weren’t told – that smoking was damaging their health. Even though plenty of medical science was being produced to show that cigarettes were extremely harmful.

Even though plenty of medical science was being produced to show that cigarettes were extremely harmful.

So OK then, I hear some readers asking, if we don’t feed our infants baby rice, baby cereal, baby porridge, mashed potato, kumara, bread, pasta, noodles, crackers, biscuit, rusks, and other starch – then what the heck do we feed a baby instead?

Well, the answer is pretty simple, as is the solution: primarily vegetables and fruit – topped up with some protein. If you do have to use baby rice, or include potato or kumara in your baby mash, do so sparingly and definitely not every day. Ideally your infant should stick to this diet from 6 months right through to 12 months. And only after 1 year of age, and lots of teeth in the mouth, should starchy food start to become the staple part of your baby’s diet.

There are certainly experts who may disagree with some of this menu’s aspects – but, for today there’s only one thing that all nutritionists agree on, and that is that there are opponents to all opinions. At the end of the day, you should go with your gut, and do what you think is best for your bub.

At the end of the day, you should go with your gut, and do what you think is best for your bub.

Check out our Baby foods recipe section for more infant meal ideas

3.6 5 votes

Article Rating

The truth about serving grains and other starches to your baby

Can babies and toddlers digest starch? If you search for the answer to this question online, you’ll run into dire warnings of the dangers of giving starch to babies and kids under 2. People say that starch just “rots” in your baby’s gut and that they don’t have the enzymes they need to digest it. Serious warnings are given about this, completely shaming parents (in my opinion) for listening to “mainstream recommendations” that tell you to give your baby starchy foods as one of their first meals – because it causes food allergies and a host of other problems, or so they say…

Honestly, that’s a bit dramatic.

All this does is make you feel like if you’ve given your baby cereal, toast, or heck – even sweet potatoes- you’ve done something wrong.

This is a subject that you’ll see pop up in many-a-Facebook group, and on online blogs, and I’m here to get down to the real truth. I hate false fears in the nutrition world, let alone in the baby nutrition world, so let me clear this myth up right here and now.

If you’d like to listen to me debunk this myth, tune into the podcast episode here – you can even download it and save it for later!

What even is starch?Starch is a type of complex carbohydrate made from lots of glucose molecules bonded together in long, branching chains. It’s a plant’s way of storing glucose – aka energy. Our brains use glucose directly, so we have to be able to break starch down into glucose in order to literally live and have energy. Starches are found, not just in grains, but in root vegetables, winter squashes, beans, and some fruits, like bananas. So this is not just an issue about grains!

How do we digest starch?Here’s where the research comes in, and this is going to get a bit scientific, but let’s break it down. The digestion of starch actually begins in the mouth! There’s an enzyme called salivary amylase that starts to break down those large chains of glucose that form the starch, so that it’s partially digested. Then it makes its way down to the small intestine where pancreatic amylase – different from salivary amylase – is secreted by the pancreas and breaks it down even further (with the help of some other enzymes) until it’s only glucose molecules that can be absorbed directly.

The digestion of starch actually begins in the mouth! There’s an enzyme called salivary amylase that starts to break down those large chains of glucose that form the starch, so that it’s partially digested. Then it makes its way down to the small intestine where pancreatic amylase – different from salivary amylase – is secreted by the pancreas and breaks it down even further (with the help of some other enzymes) until it’s only glucose molecules that can be absorbed directly.

Ok, so now let’s put it into the context of babies and their digestion, because it does differ slightly from adults. When babies are on an all breastmilk or formula diet, the type of carbohydrates they’re digesting are all simple sugars, primarily lactose. When they start solid foods, they’re adapting to starches for the first time. And to be clear, many cultures around the world do offer starch as one of the first foods, such as cereal or porridge.

And it’s interesting to think about this because if you look at the research around the digestive system of newborn babies, they actually don’t have any pancreatic amylase in the small intestine. Now, as the months go on, and they approach six months of age, they do start to develop more and more of it – and by 4-6 months of age, they do have some pancreatic amylase, but way less than the amount found in older kids and adults.

Now, as the months go on, and they approach six months of age, they do start to develop more and more of it – and by 4-6 months of age, they do have some pancreatic amylase, but way less than the amount found in older kids and adults.

If I’m honest, what doesn’t make sense, at first, is how they seemed to be able to digest starch perfectly fine, without much pancreatic amylase! In this research, no issues occurred with digestion, nor were there really any negative symptoms at all. And to me, that part does make sense when I think about it. If we look at what babies are fed all around the world, generally those first foods are all starchy. In Tanzania they serve millet flour at 3 months; corn porridge at 3 months in Zimbabwe; beans and rice at 4 months in Brazil. And these are just a few examples. So how can it be that babies all around the world are able to digest starch, and have been able to for centuries, if they lack the enzymes to do so? Why did all these babies not have any issue digesting these foods, for generations?

Time for some more research. I found a small study that examined how much starch was found in a baby’s poop (which therefore indicates how much of it was digested), after various amounts were given to the babies, and at various ages. This study found that very little starch ended up in these babies’ diapers. When they were given between 1 tablespoon and ½ cup of starch per day, the babies appeared to digest more than 99% of it. The researchers then tried a larger dose, and actually gave several 1 month olds a full cup of rice starch. Three of these infants absorbed more than 99% of this amount. Two absorbed just 96%, with the other 4% ending up in their diapers, along with some diarrhea. In other words, within the first few months of life, babies can digest small amounts of starch just fine, but give them too much, and you’ll see some diarrhea. Obviously I’d never recommend giving 1 month old babies solids anyway, starch or no starch. And I’ve mentioned before that one of the MANY reasons why you should wait until 6 months of age, or so, to introduce solids is to ensure that their digestive system is ready.

I found a small study that examined how much starch was found in a baby’s poop (which therefore indicates how much of it was digested), after various amounts were given to the babies, and at various ages. This study found that very little starch ended up in these babies’ diapers. When they were given between 1 tablespoon and ½ cup of starch per day, the babies appeared to digest more than 99% of it. The researchers then tried a larger dose, and actually gave several 1 month olds a full cup of rice starch. Three of these infants absorbed more than 99% of this amount. Two absorbed just 96%, with the other 4% ending up in their diapers, along with some diarrhea. In other words, within the first few months of life, babies can digest small amounts of starch just fine, but give them too much, and you’ll see some diarrhea. Obviously I’d never recommend giving 1 month old babies solids anyway, starch or no starch. And I’ve mentioned before that one of the MANY reasons why you should wait until 6 months of age, or so, to introduce solids is to ensure that their digestive system is ready. But it just goes to show that even at that young age, it’s still possible for babies to digest the majority of the starch that they ingest.

But it just goes to show that even at that young age, it’s still possible for babies to digest the majority of the starch that they ingest.

SO this still begs the question..how??? Well, there are a few theories that help explain why.

Reasons why babies CAN digest starch- Babies make lots of salivary amylase which reaches near adult levels by 6 months of age. This enzyme survives the acidic conditions of the stomach reasonably well, and therefore even breaks down starch in the stomach after travelling there on the food from the mouth. So it basically works overtime to get the job done – first in the mouth and then in the stomach to continue the job there.

- Human breastmilk has lots of amylase! It’s actually present in the highest amount early on in colostrum, probably to make up for the fact that at this point babies only have very little salivary amylase and obviously no pancreatic amylase. And, breastmilk amylase continues to work in the small intestine in much the same way salivary amylase does – it survives acidic conditions in the stomach and works on breaking down the starch in the small intestine.

What’s also so cool is that there are proteins in the breastmilk that protect breastmilk amylase, and one study showed the ability for only 100 ml of breastmilk to digest 20 g of starch in an hour! To put this into context, that’s about ⅔ cup of cereal, so clearly the breastmilk amylase works very efficiently, even without pancreatic amylase being present.

What’s also so cool is that there are proteins in the breastmilk that protect breastmilk amylase, and one study showed the ability for only 100 ml of breastmilk to digest 20 g of starch in an hour! To put this into context, that’s about ⅔ cup of cereal, so clearly the breastmilk amylase works very efficiently, even without pancreatic amylase being present. - Glucoamylase helps out in the small intestine too. This is another enzyme found in the small intestine, which also breaks down the glucose molecules in starch, and is actually extremely active in infants and present in high quantities for them as early as 1 month of age. So this clearly does the job for digesting starch when pancreatic amylase can’t. At this point it’s becoming clear that the digestion doesn’t operate in the same way as it does for adults, but it does still operate.

- A baby’s body produces more amylase as carbs are introduced. Interestingly, it seems that once complex carb-containing food is introduced to your baby, their body responds by secreting more amylase.

The same thing occurs with protein introduction and trypsin, the enzyme that digests protein. This makes so much sense! Their body is going to respond based on what they’re eating – body’s are reactive and built to do exactly this.

The same thing occurs with protein introduction and trypsin, the enzyme that digests protein. This makes so much sense! Their body is going to respond based on what they’re eating – body’s are reactive and built to do exactly this. - Starch fermentation in the large intestine promotes a healthy gut microbiome. Finally, critics have always said that a portion of starch doesn’t get digested in the small intestine, and therefore it sort of sits and “rots” there. But the truth is, this happens for adults too! And what the research actually shows is that instead of “rotting” in the small intestine, it moves into the large intestine and ferments. This process helps provide “food”, if you will, to the good bacteria in our gut, and therefore promotes a healthy gut microbiome. So for babies, there’s a significant amount of starch that does this in the large intestine. And this actually happens for an important reason. The beneficial bacteria it’s feeding when it ferments improves a baby’s ability to absorb nutrients, and is used as a source of energy when needed.

I recommend including starch in your baby’s diet, and there are a few reasons I want to go over to explain why I recommend this, and why I think we actually need to be careful about limiting starch in a baby’s diet.

- Waiting too long to introduce grains to your baby could end up increasing the risk of developing celiac disease, Type 1 diabetes, and a wheat allergy. There seems to be a window of opportunity in mid-infancy – probably between about 5 to 7 months – where introduction to a variety of foods, including grains, starches, and gluten, decreases your baby’s risk of developing these chronic diseases, or wheat allergy, later on. This is basically the same concept I teach when it comes to introducing the top allergens early and often, which is based on the most updated recommendations. Doing this allows the body to respond to the proteins and create antibodies in order to handle those proteins and recognize them when they’re ingested.

Therefore, decreasing the risk of a reaction, which is presumably the same idea as a baby’s ability to produce amylase in response to the introduction of starchy foods.

Therefore, decreasing the risk of a reaction, which is presumably the same idea as a baby’s ability to produce amylase in response to the introduction of starchy foods. - Eliminating starch can make it more difficult for babies to get the nutrients they need. Let’s look at the obvious example, infant cereals. These are generally fortified with iron, which is one of the nutrients that is more likely to be deficient in infants. Now as you know, I also recommend offering other sources of iron to your baby, but using iron-fortified cereals is a really simple way to ensure your baby is getting the nutrients they need, and can definitely be part of a varied diet for your baby. I know lots of families do use them, so if we look at cutting those out because they contain starch, all of a sudden we’ve lost a really easy, convenient source of iron for your baby. In general, cutting out starches means cutting out a huge portion of your baby’s nutrition sources, meaning it will be more difficult for them to get the nutrients that they need, which can lead to more problems later on.

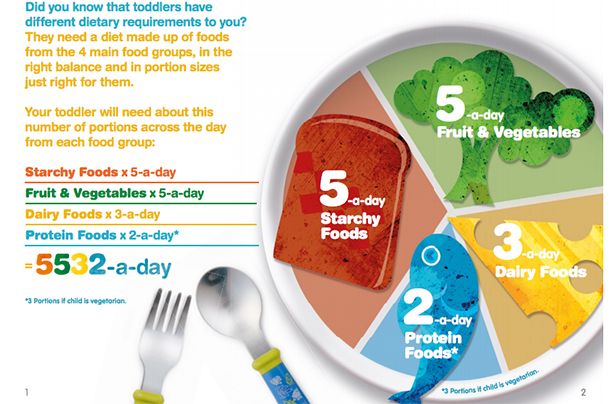

- Starch is found in so many foods, removing it from your baby’s diet takes away a lot of food options for them. This concern about starch digestion tends to be focused on avoiding grains, but remember that legumes and many fruits and vegetables also have lots of starch. So, if you truly tried to avoid starch, you would really be limiting your baby’s opportunities to get the nutrients they need (as mentioned above), and to experience different tastes and textures. Offering your baby a variety of foods is really important, and so that will always be my recommendation. Obviously in the case of allergies or intolerances, certain limitations will be necessary. But not including those circumstances, eating a variety of foods from all the food groups helps to ensure that your baby gets all the nutrients they need. And the exposure that your baby gets from being offered such a wide variety of foods is crucial in preventing picky eating too.

The bottom line is that it’s safe to feed babies starchy foods. They can digest them, and they are one part of a varied, balanced diet for babies that are ready to begin eating solid foods.

They can digest them, and they are one part of a varied, balanced diet for babies that are ready to begin eating solid foods.

Interested in learning what foods are best to give your baby, how to serve them, how to prevent picky eating, and advance your baby onto finger foods without any fear or overwhelm? My Baby Led Feeding course is for you so you can confidently move through each phase of feeding to prevent picky eating!

References:- Hadorn, B. et al. Quantitative assessment of exocrine pancreatic function in infants and children. J. Pediatr. 73, 39–50 (1968).

- Zoppi, G., Andreotti, G., Pajno-Ferrara, F., Njai, D. M. & Gaburro, D. Exocrine Pancreas Function in Premature and Full Term Neonates. Pediatr. Res. 6, 880–886 (1972).

- Fomon, S. J. Infant Feeding in the 20th Century: Formula and Beikost. J. Nutr. 131, 409S–420S (2001).

- Pelto, G. H., Levitt, E. & Thairu, L. Improving feeding practices: current patterns, common constraints, and the design of interventions. Food Nutr. Bull. 24, 45–82 (2003).

- De Vizia, B., Ciccimarra, F., De Cicco, N. & Auricchio, S. Digestibility of starches in infants and children. J. Pediatr. 86, 50–55 (1975).

- Rossiter, M. A., Barrowman, J. A., Dand, A. & Wharton, B. A. Amylase Content of Mixed Saliva in Children. Acta Pædiatrica 63, 389–392 (1974).

- Sevenhuysen, G. P., Holodinsky, C. & Dawes, C. Development of salivary alpha-amylase in infants from birth to 5 months. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 39, 584–588 (1984).

- Murray, R. D. et al. The Contribution of Salivary Amylase to Glucose Polymer Hydrolysis in Premature Infants. Pediatr. Res. 20, 186–191 (1986).

- Rosenblum, J.

L., Irwin, C. L. & Alpers, D. H. Starch and glucose oligosaccharides protect salivary-type amylase activity at acid pH. Am. J. Physiol. 254, G775–780 (1988).

L., Irwin, C. L. & Alpers, D. H. Starch and glucose oligosaccharides protect salivary-type amylase activity at acid pH. Am. J. Physiol. 254, G775–780 (1988). - Shahani, K. M., Kwan, A. J. & Friend, B. A. Role and significance of enzymes in human milk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 33, 1861–1868 (1980).

- Jones, J. B., Mehta, N. R. & Hamosh, M. Alpha-Amylase in Preterm Human Milk. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1, 43–48 (1982).

- Heitlinger, L. A., Lee, P. C., Dillon, W. P. & Lebenthal, E. Mammary Amylase: a Possible Alternate Pathway of Carbohydrate Digestion in Infancy. Pediatr. Res. 17, 15–18 (1983).

- Lindberg, T. & Skude, G. Amylase in human milk. Pediatrics 70, 235–238 (1982).

- Hegardt, P., Lindberg, T., Börjesson, J. & Skude, G. Amylase in human milk from mothers of preterm and term infants.

J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 3, 563–566 (1984).

J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 3, 563–566 (1984). - Lee, P. C., Werlin, S., Trost, B. & Struve, M. Glucoamylase activity in infants and children: normal values and relationship to symptoms and histological findings. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 39, 161–165 (2004).

- Lebenthal, E. & Lee, P. C. Glucoamylase and disaccharidase activities in normal subjects and in patients with mucosal injury of the small intestine. J. Pediatr. 97, 389–393 (1980).

- Shulman, R. J., Wong, W. W., Irving, C. S., Nichols, B. L. & Klein, P. D. Utilization of dietary cereal by young infants. J. Pediatr. 103, 23–28 (1983).

- Christian, M. T. et al. Modeling 13C Breath Curves to Determine Site and Extent of Starch Digestion and Fermentation in Infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. 34, 158–164 (2002).

- Stephen, A. et al.

The role and requirements of digestible dietary carbohydrates in infants and toddlers. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 765–779 (2012).

The role and requirements of digestible dietary carbohydrates in infants and toddlers. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 765–779 (2012). - Wong, J. M. W., de Souza, R., Kendall, C. W., Emam, A. & Jenkins, D. J. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 40, 235–243 (2006).

- Christian, M. T. et al. Starch fermentation by faecal bacteria of infants, toddlers and adults: importance for energy salvage. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 57, 1486–1491 (2003).

- Scheiwiller, J., Arrigoni, E., Brouns, F. & Amadò, R. Human faecal microbiota develops the ability to degrade type 3 resistant starch during weaning. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 43, 584–591 (2006).

- Norris, J. M. et al. Risk of celiac disease autoimmunity and timing of gluten introduction in the diet of infants at increased risk of disease. J.

Am. Med. Assoc. 293, 2343–2351 (2005).

Am. Med. Assoc. 293, 2343–2351 (2005). - Norris, J. M. et al. Timing of initial cereal exposure in infancy and risk of islet autoimmunity. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 290, 1713–1720 (2003).

- Poole, J. A. et al. Timing of Initial Exposure to Cereal Grains and the Risk of Wheat Allergy. Pediatrics 117, 2175–2182 (2006).

PrevPrevious#66: Can babies digest starch?

Next#67: How to serve peanuts to babies and toddlersNext

SHARE THIS POST

Starch in baby food - benefits, harm, purpose

Why manufacturers add starch. Is it harmful to the child's body or is it a harmless additive that allows manufacturers to save money? Let's figure it out together.

Contents

- What is starch

- What is it made of

- Modified starch

- Friend or foe?

- Benefits and harms for children

When it comes time to introduce complementary foods, parents carefully choose each product. This is understandable - the baby should receive all the best, and manufacturers are not always trustworthy. Studying the labels on jars, moms and dads learn that starch in baby food is found in milk mixtures and curds, fruit and vegetable purees. And it's not just starch, but modified! “It’s good that you read it,” the parents say and put the jar back on the shelf.

This is understandable - the baby should receive all the best, and manufacturers are not always trustworthy. Studying the labels on jars, moms and dads learn that starch in baby food is found in milk mixtures and curds, fruit and vegetable purees. And it's not just starch, but modified! “It’s good that you read it,” the parents say and put the jar back on the shelf.

What is starch

Proponents of healthy eating and nutritionists say some pretty unpleasant things about it. It is said that an excess of this substance can cause excess weight. But for a person leading an active lifestyle, starchy foods in reasonable quantities become a source of energy.

Starches are simple sugars arranged in long chains. The main component of the polysaccharide is glucose, which gives us vital energy. Polysaccharide chains bend and fold to form microgranules. It is they who creak when we rub starch with our fingers.

Polysaccharides for plants also serve as an energy accumulator, so they are abundant in seeds and roots (tubers). Half of this substance consists, for example, of wheat and corn. The white powder has neither taste nor smell, it does not dissolve in water, but at high concentration it forms a viscous mass - a paste.

Half of this substance consists, for example, of wheat and corn. The white powder has neither taste nor smell, it does not dissolve in water, but at high concentration it forms a viscous mass - a paste.

What

is made ofMany plants are rich in this polysaccharide, it is quite easy to extract it, so there is no point in artificial synthesis - the product is always natural. They make it from potatoes, corn, rice, wheat, sorghum, etc. - the species differ slightly in the presence of additional substances and properties.

Modified starch

This is not a genetic modification - starch has no genes because it is not an organism. Modifications relate to the structure of the polysaccharide: long chains of molecules are split and lose their activity when interacting with water. Baby food with this substance is not too thick and does not cause constipation.

We use a modified thickener without thinking about it. For example, this ingredient is found in store-bought sauces, creams, pastries, sausages and frankfurters, mayonnaise, jelly.

Friend or foe?

The debate about the dangers and benefits of starch will continue until the parties agree on the obvious - it's all about quantity.

Pros:

- Rich source of energy. Thanks to this substance, cereals, potatoes, bread, pastries give a feeling of satiety for a long time.

- Massages the intestines into a ball to stimulate and improve digestion.

- Protects the digestive tract from organic acids found in fruit puree for children. The enveloping properties of kissels and porridges are well known.

- Creates favorable conditions for the development of beneficial bacteria in the colon.

- Normalizes stool. The polysaccharide is able to absorb excess fluid in the intestines.

- Contains phosphorus, calcium and potassium.

Arguments against:

- Causes constipation if taken in excess.

- May cause an allergic reaction.

- Increases the calorie content of the main product and promotes weight gain.

- Rich source of carbohydrates, devoid of vitamins.

Benefits and harms for children

Children are able to assimilate starches from birth - scientific articles and abstracts have been written about this. The necessary enzyme glycoamylase is formed in the intestine before birth and allows the digestion of polysaccharides from the first day of life. Another enzyme (amylase) is found in the saliva of infants and in the small intestine. In addition, enzymes come with mother's milk. A small amount of thickener in baby food, a healthy child will absorb easily.

Rice, corn or potato starch is commonly added to purees and milk formulas.

- Corn - gentle, almost no thickening of the food

- Rice - forms a denser texture. Creates an environment for the growth of beneficial lactobacilli and bifidobacteria.

- Potato - used mainly by domestic producers. Causes allergic reactions more often than other polysaccharides.

Baby food jars are added with a thickener to make feeding easier. The child gets used to food thicker than milk, learns to chew and spit up less often. The inscription on the content of 3-6% starch on baby food, according to the authoritative pediatrician Yevgeny Komarovsky, indicates that the product can be safely used as complementary foods.

The child gets used to food thicker than milk, learns to chew and spit up less often. The inscription on the content of 3-6% starch on baby food, according to the authoritative pediatrician Yevgeny Komarovsky, indicates that the product can be safely used as complementary foods.

starch benefits and harms

If starch is added to baby food, its benefits and harms are always a matter of discussion among parents. However, is starch so harmful if there is so much controversy about it? Should I refuse to eat dishes with him in the diet of children? Does starch have useful qualities, and how to use them in baby food?..Yes or no to starch?..

Often, baby food packages, cereal boxes or jars may contain the phrase "starch free". But why do manufacturers inform parents about the absence of starch in products? Is this product classified as harmful and should be avoided when feeding children? But many of the traditional children's products and drinks (for example, jelly) contain starch in their composition. We grew up on products that contain starch and it is simply impossible to cook them without this component. So, starch is found in potatoes, many cereals and desserts, they cook cookies and much more with it.

We grew up on products that contain starch and it is simply impossible to cook them without this component. So, starch is found in potatoes, many cereals and desserts, they cook cookies and much more with it.

Starch is one of the main polysaccharides in plants, that is, it is a complex carbohydrate. This substance is found in a certain amount in the composition of cereals, legumes and some vegetables and fruits. When starch enters the child's body, under the influence of certain enzymes, it breaks down to its constituent components, and turns into glucose.

Namely, glucose is one of the important sources of energy for the body. Especially rich in starch content are rice grains (up to 86% starch), wheat grains (up to 75% starch), as well as corn (up to 72%) and potatoes (up to 25%). Starch is one of the most common vegetable carbohydrates in the diet of both children and adults. Also, starch is actively used as a thickener for the preparation of many food products - these are mayonnaises, sausages, sauces, jelly, etc.

Starch: benefits and harms

If we talk about starch, which is used in the food industry and nutrition, it can be divided into two types - this is natural starch obtained from food, as well as refined (in other words - modified) starch. Common natural starch is obtained from potatoes, corn, and can also be found in fruits and vegetables, nuts and beans, cereal grains. In the food industry, the process of starch modification is often resorted to, it is boiled for several hours with an acid solution (weak sulfuric acid).

Natural starch has been consumed for many centuries in the diet, and it does not bring any health effects if used in moderation. Excess consumption of starchy foods leads to excess weight. But with respect to modified starch, everything is a little more complicated. Frequent and abundant consumption of a modified form of starch leads to an increase in the level of insulin in the blood and the strain of enzymes. This leads to a violation of hormonal metabolism, pathologies from the side of vision and provocation of atherosclerosis. Therefore, the benefits and harms of starch are determined, rather, by its amount in the diet, and not by the type of starch itself.

Therefore, the benefits and harms of starch are determined, rather, by its amount in the diet, and not by the type of starch itself.

By the way, it is worth noting that modified starch does not belong to GMOs: they include those products, including starch, that are obtained from genetically modified foods - potatoes, corn or rice. And it can be quite ordinary, without additional modification, starch.

Why does a child need starch?

Natural starch (unmodified and derived from natural, unexposed foods) will not harm your baby. Moreover, it helps to improve health and protect the baby. Glucose, which is released from starch, can help in the absorption of fructose from foods inside the intestines, and also has a fixing effect. In addition, starch itself helps protect the baby's stomach from aggressive influences, creating a delicate film in it. It becomes an obstacle to the action of aggressive fruit acids, which often contain sour fruits.

In addition, the addition of starch to baby food, especially vegetable or fruit purees, makes the mixture soft and homogeneous.