What do finches feed their babies

Wild Baby Finch Diet | Pets on Mom.com

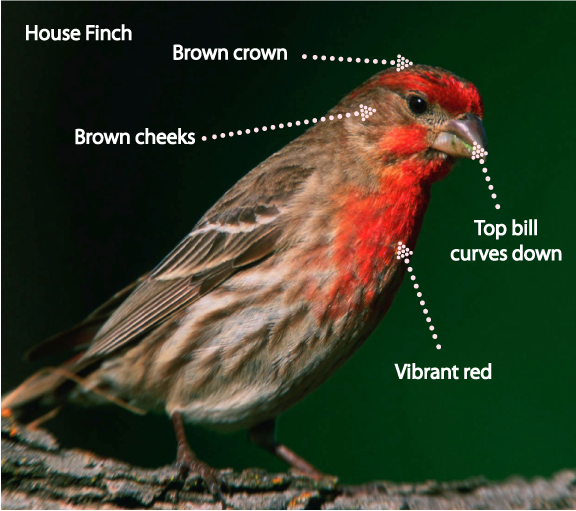

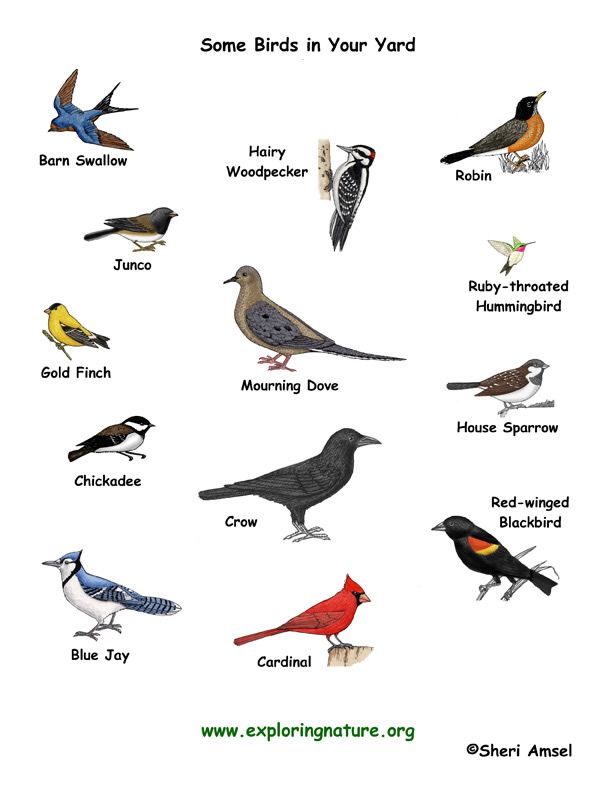

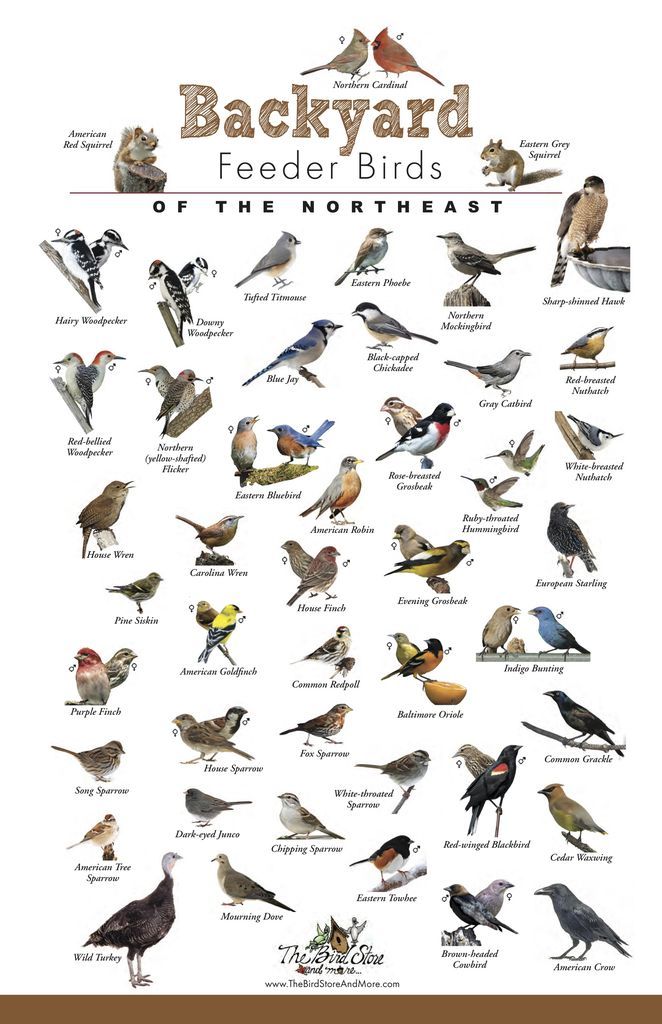

By Victoria Marinucci | Updated September 26, 2017North America serves as home for more than 20 species of finches. These small songbirds inhabit cities, woods, mountains and deserts. With such a large finch population throughout the country, you may have a nest of wild baby finches near your house or wild finch fledglings visiting your bird feeder. You can positively impact a wild baby finch's health by understanding her diet and providing nutritious food at your feeder.

Hatching and Nestling Diet

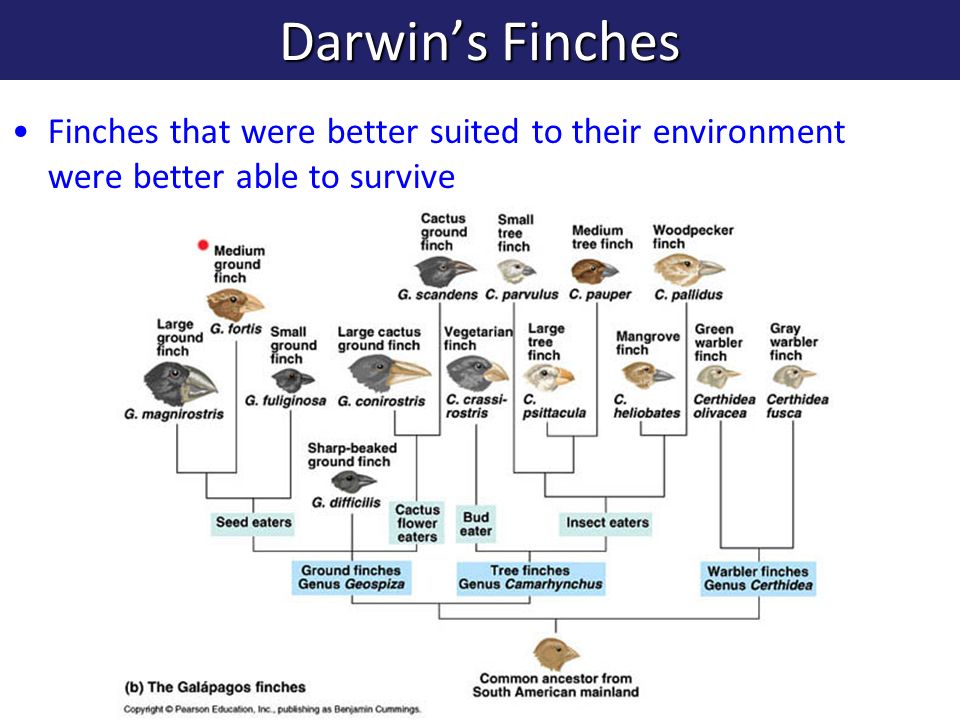

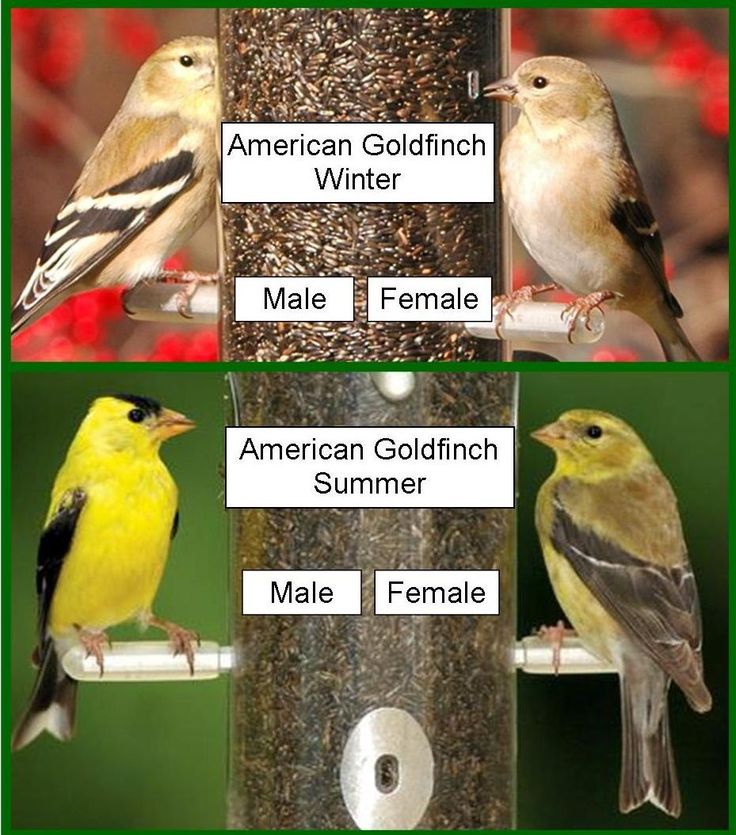

Much like a human baby, a wild baby finch requires a certain diet of foods and frequent feedings from his parents in order to stay healthy. The first week of a finch's life is the hatching stage, and it is followed by the nestling stage, which can last two weeks. During both stages, it is crucial that his mother keeps him warm and nourished by feeding him at 1 1/2- to 20-minute intervals, according to an article published in "The Condor. " Finches generally feed their babies a variety of regurgitated seeds, such as the sunflower seeds and dandelion seeds that house finches mainly feed their young. Brambling and American goldfinch feed their babies small insects, including aphids and gnats; the diet of those finches consists mainly of insects.

Fledgling Diet

Two to four weeks after hatching, the wild baby finch becomes a fledgling. During this stage, the finch's wing muscles have developed and her flight feathers have grown in. The wild baby finch ventures from the nest, though she is still dependent on her mother and father for care. She still relies on her parents to bring the seeds and insects she received in the nest. The fledgling period lasts one to two weeks.

Juvenile Diet

After the fledgling period, the baby finch graduates to the juvenile stage and begins eating on his own. He gradually learns to eat an adult diet. Though his diet still contains seeds and insects, it also includes plants, such as thistles and nettles that adult goldfinches eat and wild berries and nectar that mature house finches eat. He will remain a juvenile until he becomes a fully fledged adult at 3 to 4 months old.

He will remain a juvenile until he becomes a fully fledged adult at 3 to 4 months old.

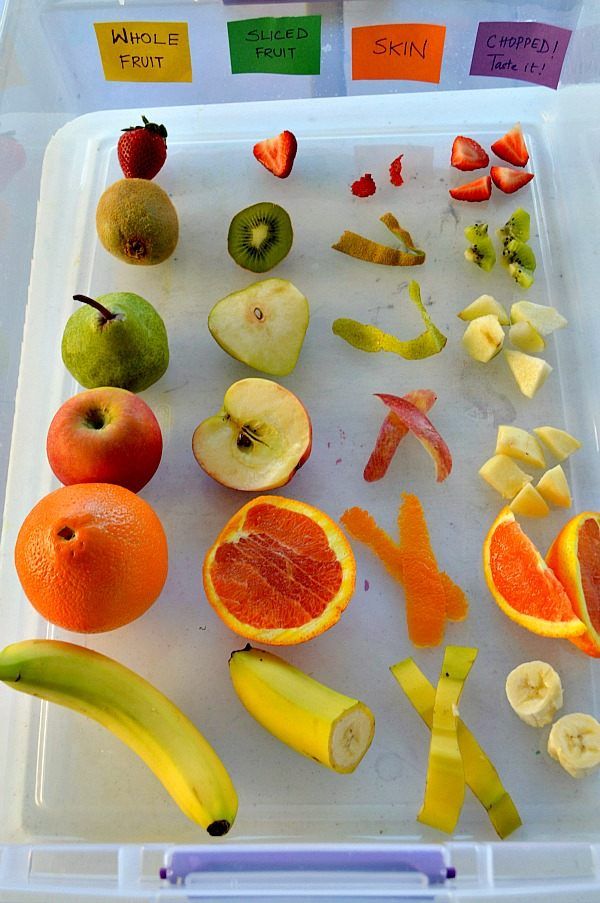

Bird Feeder Food

Even though a wild baby finch should not be directly handled or fed, you can help her diet by attracting finch parents and fledglings to your bird feeder. Because the parents and their babies eat seeds and insects, you can place wild bird seed containing whole sunflower seeds, sunflower kernels and millet as well as insects such as meal worms or wax worms in your bird feeder. Wild bird seed is available at pet stores, garden stores and most supermarkets, and pet stores sell insects. You also can offer unconventional food such as breads, most fruits and suet. Changing bird seed frequently ensures the food is fresh. Damp or old food may cause illness in birds.

Orphans

If you find an orphaned wild baby finch, you should not care for or feed him, but you can help him. The first task to establish whether the finch is a fledgling or a nestling. "In order to determine whether the bird is a nestling or a fledgling allow the baby bird to perch on your finger. If it is able to grip your finger firmly than it is a fledgling," states the website Wild Bird Watching. If he is a fledgling, he should be left alone. His parents will continue to feed him as he learns to fly. A nestling, however, should be returned to his nest. If you cannot find the nest, your area's wildlife rehabilitator can properly care for the wild baby finch.

"In order to determine whether the bird is a nestling or a fledgling allow the baby bird to perch on your finger. If it is able to grip your finger firmly than it is a fledgling," states the website Wild Bird Watching. If he is a fledgling, he should be left alone. His parents will continue to feed him as he learns to fly. A nestling, however, should be returned to his nest. If you cannot find the nest, your area's wildlife rehabilitator can properly care for the wild baby finch.

Warning

Some foods are dangerous to a baby and an adult finch's health. Among the foods to avoid are those containing caffeine, including coffee beans and chocolate. A finch cannot metabolize caffeine, resulting in dehydration and seizures. Also, vegetable oils can destroy feathers' insulating qualities needed for warmth. Lastly, stale and moldy food, which can cause respiratory infections, should be avoided.

References

- Wild Bird Watching: Baby Birds--Should I Help?

- "The Auk;" A Study of the House Finch; W.

H. Bergtold, M.D.; January 1913

H. Bergtold, M.D.; January 1913 - Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment: American Goldfinch (Carduelis Tristis)

- RSPB, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds: What Food To Provide--Bird Seed Mixtures

- "The Condor;" Observations On Nesting Behavior Of The House Finch; Fred G. Evenden; March-April 1957

Photo Credits

Writer Bio

Victoria Marinucci has been writing since 2002. Her articles have appeared in Pennsylvania newspapers as the "Bucks County Courier Times," and "The Intelligencer." She has also had numerous articles published on the news site, phillyBurbs. Marinucci earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from Penn State University.

How to Care for House Finch Babies

By Nadelee Biondi | Updated September 26, 2017Things You'll Need

Cage or box

Flannel or fleece fabric

Paper towels

Heat lamp or heating pad

Thermometer

Pre-made baby finch food

Pedialyte

Eye dropper or medication syringe

Bugs (crickets or mealworms)

Nest (can be a commercial finch nest)

Food and water bowls that attach to the cage bars

House finches are active but nervous birds. Their antics are fun to watch; however, unlike a parrot that can be held, a finch is not the right bird to have if the owner wants one that's loveable and playful. Finches don't enjoy cuddling -- although they're playful among themselves -- and holding them causes these birds stress. They make nests in pockets placed in the cage, and this is where finches will raise their young. Occasionally, when a parent dies or is unable to care for the baby, human intervention is needed. Though the babies are fragile, it is possible to raise them by hand until they can be introduced to other finches.

Their antics are fun to watch; however, unlike a parrot that can be held, a finch is not the right bird to have if the owner wants one that's loveable and playful. Finches don't enjoy cuddling -- although they're playful among themselves -- and holding them causes these birds stress. They make nests in pockets placed in the cage, and this is where finches will raise their young. Occasionally, when a parent dies or is unable to care for the baby, human intervention is needed. Though the babies are fragile, it is possible to raise them by hand until they can be introduced to other finches.

Find a box or cage that will protect the baby finch and give easy access to feed and care for it. Ensure the baby cannot escape before it's old enough to be placed in a cage with older finches.

Make a nest in the corner of the cage or box. It can be made of fleece or flannel fabric, and should have sides high enough so the baby cannot roll out of it. Cover the area for the baby finch with a folded paper towel.

Place the cage with the baby finch where the heat can be regulated. The baby must not get too hot or too cold. The temperature should be regulated between 88 and 92 degrees F. A heat lamp above the cage works well, as does a heating pad under it.

Put a thermometer in the cage between the nest and the wall of the cage. It will need to be continuously watched and the heat adjusted, until a steady temperature is finally achieved.

Purchase a ready-made seed mixture from a pet-supply or feed-supply store and a bottle of Pedialyte.

Set up a schedule for feeding the baby finch around the clock at timed intervals. Watch the crop in the baby's neck, as this tells when the baby's hungry; if it is flat, or puffed out, the baby finch is hungry and needs to be fed.

Mix the ready-made seed with the Pedialyte so that it's watery.

Feed the baby finch by filling an eyedropper with the ready-made seed mix. A syringe used to give human babies medicine will also work. Give the baby a little at a time, allowing the baby to take the food at its own pace. Baby finches do not breathe when they are feeding. Feed the baby small amounts at a time, allowing it to breathe in between. Do not overfeed the baby, as this could cause death.

Baby finches do not breathe when they are feeding. Feed the baby small amounts at a time, allowing it to breathe in between. Do not overfeed the baby, as this could cause death.

Change the paper towel in the baby finch's nest before placing the baby back in it. The baby will probably fall fast asleep.

Mash up small bugs, occasionally mixing them with the seed mixture and sufficient quantities of water after the first two weeks of just feeding the seed mixture. Keep feeding the baby finch at regular intervals. Bugs provide perfect protein to keep the growing bird healthy. It's also okay at this point to start giving the baby water, small drops at a time, separate from the food -- although it's also okay to continue with Pedialyte.

Replace the homemade bird nest in the box with an actual finch nest, purchased from a pet store, in a cage. The baby finch is strong enough at this stage when it can stick its head out of the nest to let the caregiver know it's hungry. No matter what kind of directions a person is given for raising a baby bird, however, the chances of it surviving are slim if it is newly hatched. Remember though that even if it does not survive, it was held by your loving hands that tried.

Remember though that even if it does not survive, it was held by your loving hands that tried.

Provide crushed birdseed in a bowl that attaches to the inside of the cage, along with a water container. At three weeks, the baby is large and agile enough to jump from the opening of the nest to the bowls and is now actively feeding and watering itself. It's okay to leave the baby in this cage for its lifetime.

Put the baby finch at five weeks of age into a cage with other finches. It is now old enough to be accepted and not picked on by the others. Keep its cage as it was for the time being, in case there are problems and it needs to be moved back into its first cage. It's okay to introduce another finch to the baby in the baby's cage as well.

Keep the baby finch's bedding clean at all times, replacing the paper towel as often as needed. Keep sudden noises to a minimum, as baby birds startle easily. Keep the cage and the baby in an area not accessible by children or other pets.

Warnings

Do not overheat or underheat the baby finch, and do not force or over feed it -- as all of these conditions can cause the death of the baby finch.

References

- AnimalAmigo.com: Caring for Baby Finches

- AskDeb.com: What do You Feed a Baby Bird: Doug Brinlee

- Birds n Ways: How to Handfeed Finches: Kristine Spencer

- Bird Guys: How to Care for Finches

- Animal-World: All About Finches

- Beautiful Song Birds: Guide to Finch Care

Photo Credits

Writer Bio

Nadelee Biondi has been writing professionally since 2004. After receiving a Bachelor of Arts in English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, she began contributing to "Sunset" and "Better Homes and Gardens." Biondi is also pursuing a Master of Arts in English literature.

How birds take care of their chicks - Notes of a Naturalist

The Animal Friend book series, 1909

8507 Even an empty bird's nest, half hidden among tree branches or on the ground, in the grass under a bush, is a very attractive picture. But it is even nicer when colorful eggs lie in the cozy recess of the nest or small chicks sit, opening their noses wide to grab the food brought by their parents. I don't know almost a single picture from the life of animals that would tell us so convincingly and clearly about the love of parents for children.

But it is even nicer when colorful eggs lie in the cozy recess of the nest or small chicks sit, opening their noses wide to grab the food brought by their parents. I don't know almost a single picture from the life of animals that would tell us so convincingly and clearly about the love of parents for children.

How defenseless, how helpless is in most cases a small creature when it finally breaks through the calcareous shell that constrains it! Without the help of the parents who gave it life, it would soon die in the most miserable way. And how old people take care of their chicks! The thought of children fills their whole soul, starting from the moment when the first egg appears in a small airy cradle, and up to the moment when the chicks separate from their parents. All their thoughts and actions are aimed at bringing safety and protection to their helpless cubs, in order to feed hungry mouths, and later, when the chicks grow up, train them so that they can exist independently in the world and would not die in the harsh worldly storms, who are waiting for them.

Here is a little miller warbler, the smallest of our warblers, has built a nest in a low currant bush. We carefully part the branches of the bush: the warbler sits on the edge of the nest, holding food in its beak. We prevented her: she was just about to feed her cubs, which, with a squeak, stretch their ugly noses towards her. With its beautiful, intelligent eyes, a pretty bird gazes intently at a stranger who has invaded her possessions. The chicks also fell silent and drew back their outstretched necks. Nothing stirs; only the caterpillar is spinning, trying to escape from the bird's beak. But here we made a movement - and immediately broke the charm with this. Warbler falls from her place to the ground at our feet and, as if with broken limbs, helplessly jumps on the ground, dragging now her wing, now her leg. Isn't she trying to divert our attention from the nest and draw it to herself, to a sick creature with broken wings? An inexperienced person tries to follow a bird jumping on the ground, which tries to take him as far as possible from her chicks, and only then will she suddenly rise from the ground and disappear into a dense bush.

And with what fearful cry the lapwings fly around us when we approach their nests! They fly very close to the enemy, they even pretend that they are going to attack him, as birds of prey do, so that a timid person positively rejoices when he manages to move away from the place where he was pursued from all sides by lapwings circling around him. with plaintive cries, and the lapwings only wanted him to leave: they hurriedly return to their nest, loudly rejoicing that they managed to avert a terrible danger from their children. Parental love makes them completely forget about the danger: courageous birds sometimes approach us so much that it seems that you can kill them with a stick. They also try to drive dogs away from their nests by attacking them. Often, lapwings, which are almost no larger than a domestic pigeon, even dare to make real attacks on dogs. More than once they have seen how they, running on the ground with outstretched wings in front of the dogs and jumping up, inflicted such blows with their beak on the head near the eyes that they put them to flight. If a separate lapwing, sitting on eggs, notices our approach only when we are already in front of it, then it begins to hobble around our feet back and forth, just as the whitethroat warbler and the rattle warbler do, in order to distract our attention from the eggs to himself, seemingly such a helpless creature.

If a separate lapwing, sitting on eggs, notices our approach only when we are already in front of it, then it begins to hobble around our feet back and forth, just as the whitethroat warbler and the rattle warbler do, in order to distract our attention from the eggs to himself, seemingly such a helpless creature.

Of course, it is hard to believe that a bird can reason in such a way that she deliberately uses this trick, which would do as much credit to her mind as to her love for children. Therefore, perhaps, those who say that fear for children deprives the bird of reason, paralyzes its muscles, are right, so that the bird acts unconsciously. But why, then, does the bird noticeably try to move away from the nest?

One day, walking along the bank of a pond, I approached a place where a small company of seagulls was sitting on their eggs in the reeds. With a piercing cry, frightened birds rose into the air and began to circle around me, crying plaintively. At the same time, as it might seem, they also wanted to drive me away by throwing their liquid stools from above, which fell near me; one such projectile hit just on my hat. The same is said about terns. Of course, it may also be that the birds do not do this intentionally, but that this excretion is caused in them only by a feeling of fear. But however much we may belittle the mind of the bird in all the examples just given, one thing is certain, that the amazing behavior of birds during nesting is in any case very favorable for the preservation of their offspring, and that the fear that seizes the birds in this case is due only to tenderness. love for the chicks, overflowing with a small bird's heart.

The same is said about terns. Of course, it may also be that the birds do not do this intentionally, but that this excretion is caused in them only by a feeling of fear. But however much we may belittle the mind of the bird in all the examples just given, one thing is certain, that the amazing behavior of birds during nesting is in any case very favorable for the preservation of their offspring, and that the fear that seizes the birds in this case is due only to tenderness. love for the chicks, overflowing with a small bird's heart.

It is remarkable that among birds, not only the mother, but also the father devotes himself to the upbringing of the young. For the most part, both the male and the female take part in the construction of the nest. Often the male chooses a place for the nest and drags material for construction there, and the female, the main craftswoman in this matter, weaves and fastens the brought material together. Very often, the male and the female take turns sitting on the eggs, at least the male is ready every minute to help the female take her place if she needs to leave the nest for a short time.

And look how carefully the bird leaves its nest and returns to it again, how it takes care that the nest also does not catch the eye of some enemy while it is not there. The skylark never rises directly from the nest, but first runs some distance along the ground, hiding behind low grass or grain shoots, until finally it flies up. Returning back, he observes the same precaution, even when the chicks have already left the nest and, whistling softly, call their mother to her, she flies over the very grass not directly to the chicks, but to a place that is not far from them, and then already on the ground imperceptibly runs up to his children. Very many birds behave similarly to this if they have eggs or chicks, for example, water hens and others.

Many birds, leaving their nest, at least for the shortest time, carefully cover the eggs from above with grass, leaves, and brushwood so that the eggs are not conspicuous.

Some hollow nesters very conscientiously carry away the droppings of chicks away from the nest. If the birds, when cleaning their nursery, simply threw out the sewage from the nest, then these sewage, accumulating near the nest, would often serve as a sure sign for various predators, betraying the presence of the nest. But smart birds do things differently.

If the birds, when cleaning their nursery, simply threw out the sewage from the nest, then these sewage, accumulating near the nest, would often serve as a sure sign for various predators, betraying the presence of the nest. But smart birds do things differently.

We are standing on the bank of a small pond. Here is a male of a graceful powdery tit, or chickadee, with a moth caterpillar in its beak, slipped into the hollow of a bird cherry tree to its chirping chicks and immediately appears again with a lump of droppings, the size of a pea, covered with a white mucous membrane. He releases it only when he is already flying over the water. Now a female appears with the same caterpillar in her beak; she also slips to her children and flies back from the nest with the same lump. This lump also disappears forever in the water. Young chicks in this respect are similar to those automatic selling devices that throw out some thing when a coin is lowered into the hole in the device. If you put a piece of food in the chick's mouth, then the swallowing movement that he does at the same time immediately causes movement in the back of the abdomen, and you can be almost sure that the short large intestine will immediately push out a lump of droppings, the undigested remnants of food swallowed earlier.

You already know that brood birds remain in the nest only until they are thoroughly dry, and then, without any fuss, run away from it with their mother.

Things are quite different with chicks. What helpless creatures their chicks are! They know only one thing: to open their noses wide in order to perceive food and drink. The parents feed them a curd-like substance, which is secreted in large quantities in pigeons when they have chicks, in the two lateral projections of their crop. It is a crumbly substance with the smell of rancid oil. It is sometimes called "milk", but in composition it has nothing to do with the milk of mammals, since it does not contain any casein or milk sugar contained in milk. In other birds, such as finches or plantains, the crop serves to soften the seeds in it before giving them to the chicks. This makes the food more digestible. And, for example, the crossbill, if it did not have an enlarged esophagus similar to a goiter, perhaps, could not feed its chicks at all. Klest often starts hatching chicks in winter, when he has only hard seeds of our coniferous trees at his disposal. This is not at all suitable food for small chicks, if the seeds were not first softened in the goiter. However, most granivorous birds, such as sparrows, finches, plantains, feed their chicks at first exclusively with insects, as a more digestible food, and only later move on to heavier food; although on the other hand there are birds such as, for example, linnet, which from the very beginning feed on plant foods.

Klest often starts hatching chicks in winter, when he has only hard seeds of our coniferous trees at his disposal. This is not at all suitable food for small chicks, if the seeds were not first softened in the goiter. However, most granivorous birds, such as sparrows, finches, plantains, feed their chicks at first exclusively with insects, as a more digestible food, and only later move on to heavier food; although on the other hand there are birds such as, for example, linnet, which from the very beginning feed on plant foods.

When, after a few weeks of careful care from their parents, the little chicks fledge and their dark eyes begin to boldly look at the world around them, some kind of anxiety seizes the small children's society. It becomes crowded in the nest for everyone: one touches his neighbor with his wing, the other even tries to clear his place by force with the help of his legs. Finally, the strongest of the chicks squeezes upward from the tightness. Having made a big leap, he immediately reaches the edge of the nest or even sits already on a neighboring branch, looking around him with fear and at the same time pleased with his first feat, which he succeeded so much, as his parents assure him of this with their body movements and gentle inviting sounds. .

.

I have seldom been able to observe the flight of chicks from the nest myself. But still, I was lucky to see several times how young black redstarts dared to take the first step into the world around them, and once also how the chicks of the middle spotted woodpecker left their cradle; I also saw the first experiences of flight in young swallows. The chicks behaved very differently. One chick turns out to be quite skillful: it, apparently, already quite correctly determines distances, jumps from the first branch to the next, and even dares, encouraged by the voices of its parents, to flutter to a neighboring tree. As a reward for this, he receives a caterpillar. Another rushes swiftly out of the nest and falls, fluttering its wings, to the ground, perhaps into tall grass, from which it only manages to get out with difficulty. Only young swallows showed themselves, all without exception, born flyers from the very beginning; they climbed up the wall of the nest, then spread their wings and flew to the edge of the roof, thence to the ridge of the roof, and in a short time many of them made the already safely difficult flight across the street to the roof of the house opposite. Very often it also happens that the chicks leave the nest immediately, being frightened of something, or the parents, bored with the fact that the chicks are too slow, push them over the edge of the nest themselves.

Very often it also happens that the chicks leave the nest immediately, being frightened of something, or the parents, bored with the fact that the chicks are too slow, push them over the edge of the nest themselves.

The famous German aviologist Liebe beautifully describes how a pair of peregrine falcons taught their children to fly. Two young falcons perched on a horizontal branch of an old pine, looking about them half in curiosity, half in fear, while the old male reenacted before them his magnificent exercises in the art of flying. Did he want to teach the chicks this? Or did you want to inspire courage in them? “But then the female also appeared ... Having made several strokes in the air against the wind, she headed with the help of a skillful turn to the side, into the space behind the pine tree and then, slowly moving her wings, swam past one of the chicks, but so close to him that hit him with a wing and moved him from his place. But the chick firmly clung to the bough and, without releasing it, but only waving its wings in the air, again strengthened itself in its former position. Then the mother repeated the same attempt with another chick. This time she succeeded better: the mother very easily pushed the chick with her wing, I flew far down, describing a flat arc in the air. Now the mother took up the first chick again and pushed it off the branch in the same way as the other. The chick fell down, almost to the very ground, and again returned back to its branch, rising, apparently with difficulty and staggering, into the air against the wind. But the mother did not give him rest and again swam very close to him, without touching him with her wing, as if she wanted to show him how he should behave and how to move his wings.

Then the mother repeated the same attempt with another chick. This time she succeeded better: the mother very easily pushed the chick with her wing, I flew far down, describing a flat arc in the air. Now the mother took up the first chick again and pushed it off the branch in the same way as the other. The chick fell down, almost to the very ground, and again returned back to its branch, rising, apparently with difficulty and staggering, into the air against the wind. But the mother did not give him rest and again swam very close to him, without touching him with her wing, as if she wanted to show him how he should behave and how to move his wings.

After the chicks leave the nest, the parents continue to feed them for some time. Then one can see how, for example, young redstarts, resembling small round balls of feathers, of which only a nose with a yellow border and a blunt tail stick out, sit on the fence of the garden and beg food from their parents with trembling movements, or like little swallows huddled close to each other on the crest of the roof, watching the old swallows hunt for insects, and with their diligent chirping let every swallow flying past know about their desire to get a tasty piece.

Even the sight of young sparrows sitting in the dust of the street and never ceasing with their importunate requests not only to their own mother, but to every adult sparrow, can give great pleasure. Fluttering their wings, little sparrows jump after adult sparrows, expressively shouting out their invariable: “give, give!” More than once I have observed how little screamers pestered even finches and buntings and sought from them the satisfaction of their request. And once I even saw young sparrows begging for their food from a crested lark. And the lark had no choice but to get rid of the little beggars, but to give them a few pieces.

Among the brood birds, too, the parents tenderly care for their children and teach them all the arts that may be useful to them later. First of all, we can point here to chicken birds. And if in chicken birds the father usually does not care at all or cares very little about his children, then, on the other hand, the mother devoted to them tries to make up for the lack of father's love with redoubled solicitude.

But among partridges, the male takes care of his children in the same way as the female. Fearfully looking out from which side trouble threatens them, and whether it is possible to avert it, the father runs hither and thither, while the mother, with a short warning cry, gathers the chickens around her, orders them to hide in some secret place and quickly points out to each of them shelters in grass, in grain crops, among bushes, in furrows, ruts, and so on. And when the mother finally decides that all her children are well hidden, she, together with the father, exerts all her strength to frustrate the enemy’s plan or repel the attack ... If the father thinks that the danger has passed, he begins to call the chickens to him; one after another, the chicks answer him, and the loving parents gradually gather the entire scattered company back into one place, and the father brings the children one by one and takes them to the mother, who at that time is looking after those chicks that the father has already brought to her.

And how tenderly all the swimming birds treat their young! Their chicks know how to swim from the very first day; but many aquatic birds must still learn how to dive, in order to save themselves from dangers under water and look for their food there. For example, a grebe begins training its chicks to dive by taking them under its wings and diving with them until the chicks finally lose all fear of the dark abyss and dare to do the same on their own. If the little fluffy chicks want to take a break from their exercises, they climb onto the soft and warm back of their mother or father, who continue to calmly float on the water with their expensive burden on their backs.

When, after some time, the chicks learn everything they need to know in life, their connection with their parents is interrupted. The children, carefully guarded until now, now go their own way. And if sometimes some capricious little chick still tries to hold onto its mother's skirt, as, for example, is very often observed among sparrows, then the mother angrily throws it away with its beak. Sometimes brothers and sisters remain together for some time, but this is no longer a strong union, and in the end each of them ceases to care about the others. In addition, in many birds, the parents at this time begin to think about how to start the second hatch of children, and the chicks of migratory birds, as soon as they learn to fly well, are already thinking about the flight. Did their parents tell them about this great event that is coming to them?

Sometimes brothers and sisters remain together for some time, but this is no longer a strong union, and in the end each of them ceases to care about the others. In addition, in many birds, the parents at this time begin to think about how to start the second hatch of children, and the chicks of migratory birds, as soon as they learn to fly well, are already thinking about the flight. Did their parents tell them about this great event that is coming to them?

← Bird's nests↑ Notes of a NaturalistLynx →

GDZ Pleshakov World around 3rd grade Part 1 Page. 102

Contents

- •

- Check yourself

- Homework assignments

•

1. Egg - chick - adult bird. Egg - tadpole - adult frog.

Egg - fry - adult fish. Egg - larva - pupa - butterfly.

Page 102

Check yourself

1. Insects reproduce by laying fertilized eggs. Eggs of different species of insects differ in shape, size and color. They can be white, green, yellow or red. The eggs hatch into larvae. The development of the larva may take several hours or last for many months.

They can be white, green, yellow or red. The eggs hatch into larvae. The development of the larva may take several hours or last for many months.

2. The development of fish and amphibians, they lay eggs in water bodies. From the eggs of fish, fry appear - small fish that grow up and remain to live in the water. And from the eggs of amphibians, tadpoles appear, which grow up and move to live on land.

Development of amphibians and reptiles. Amphibians lay their eggs in water bodies, and reptiles lay on the shore. Young descendants of amphibians, tadpoles, are slightly different from their adult parents. The offspring of reptiles are copies of their parents, only very small ones.

3. Birds form families. Almost all birds build nests in trees in spring. They lay their eggs in nests and incubate them in the warmth. Chicks emerge from eggs later, some birds are born covered with feathers, some are naked.

At the end of spring and beginning of summer, the chicks of many birds leave the nest. But although they are already covered with feathers, they still fly poorly. They also cannot feed themselves yet. Parents feed the chicks for some time and protect them from enemies.

But although they are already covered with feathers, they still fly poorly. They also cannot feed themselves yet. Parents feed the chicks for some time and protect them from enemies.

4. The difference is that only animals feed their young with mother's milk. Because of this, they are actually called mammals.

5. Both birds and animals take care of their offspring until the cubs become independent. Birds teach their chicks to fly, catch midges, bugs, caterpillars. Animals feed their cubs exclusively with mother's milk, they teach them to get their own food. While the cub is small, the animals take care of their offspring, protect them from enemies and teach them how to get their own food.

Page 102

Homework assignments

1. The larva is an early stage of insect development leading an independent lifestyle, which differs from the adult form. The larva emerges from the eggs.

The pupa is the stage of individual development of insects with complete metamorphosis following the larva.

A fry is a small fish that has just hatched from an egg.

A tadpole is an amphibian larva that has recently hatched from an egg.

2.

3. My grandmother has kittens every year. When I come to visit her, she allows me to play with the kittens. The cat's name is Nuska. Nyuska already knows that no one is going to offend her kids. As soon as I start stroking her, she immediately begins to purr and crawl her head under my arm. Nuska's kittens appear completely helpless and blind. They squeak funny. Nyuska feeds them with her milk and constantly licks them so that the kittens are clean. Time passes, about a week, their eyes begin to open. I think that Nuska is a very caring mother. She is very worried if one of the babies begins to meow or a stranger takes the kitten in his arms. As soon as they grow up, the grandmother distributes the kittens to new owners.