What to feed baby ravens

What Do Ravens Eat? – 15 Foods They Will Devour

More Great Content:

↓ Continue Reading To See This Amazing Video

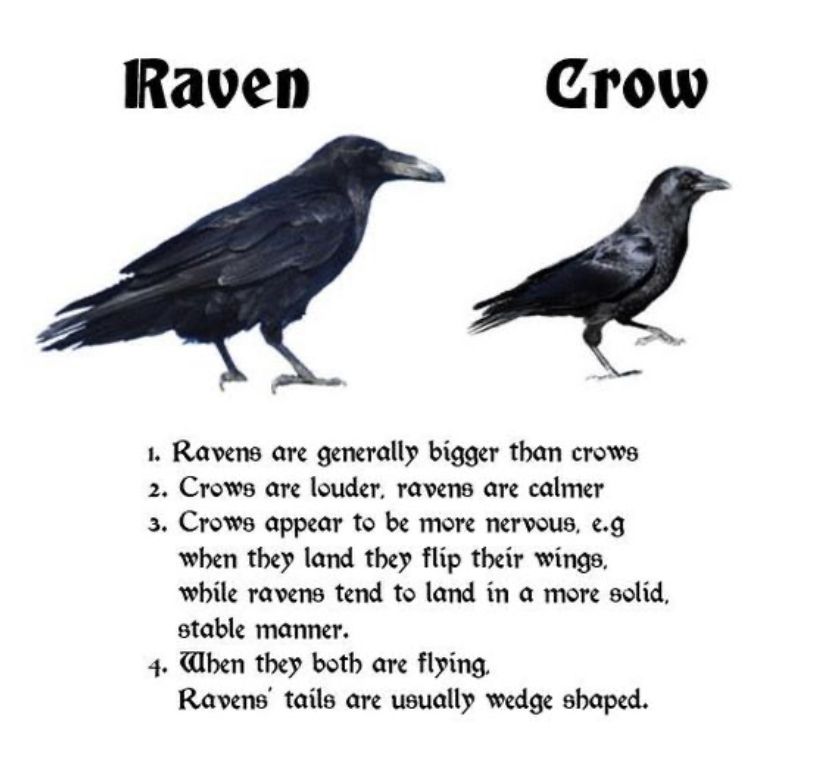

The Common raven (Corvus corax) is the type species of the genus Corvus and is found throughout the Northern Hemisphere. It is the largest of these birds and is known as a scavenger and predator that can live in a variety of climates, from the sweltering desert to the frigid tundra of the high Arctic.

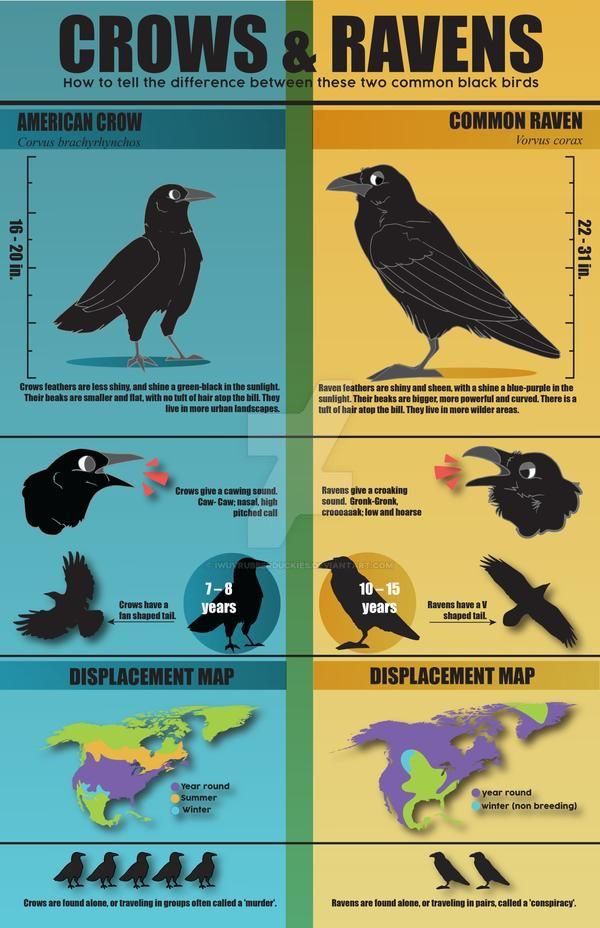

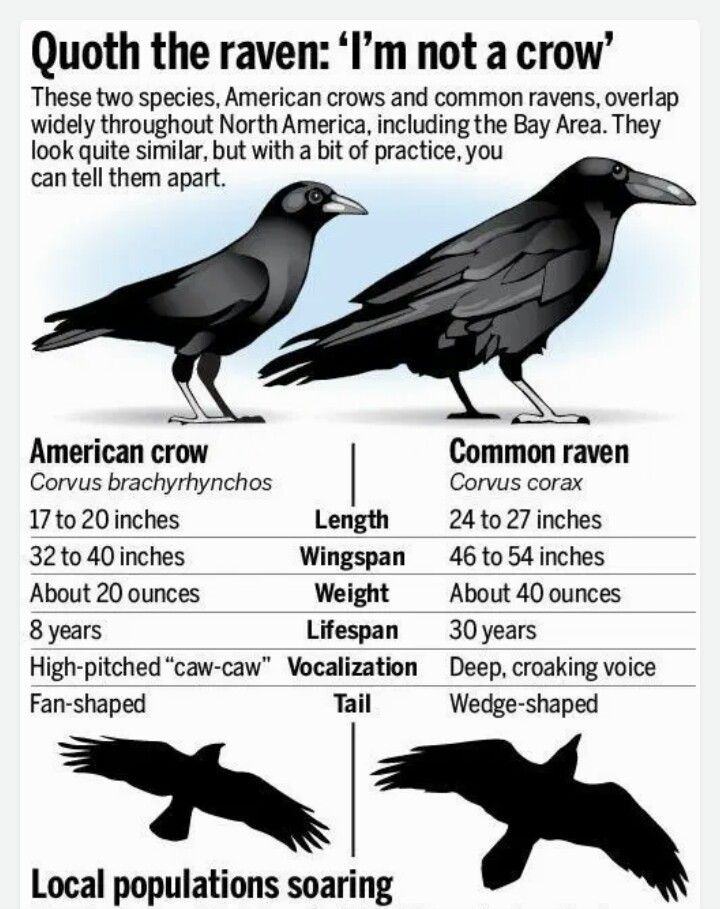

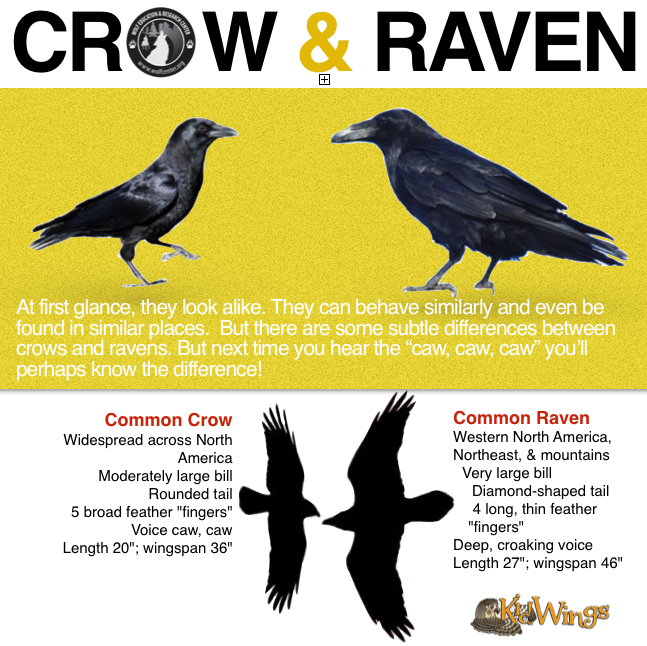

Common ravens are huge, black birds with massive beaks. They resemble American crows, both Corvidae. They are the only other all-black North American bird species except the crow. Despite popular confusion, the two birds are unique. Ravens are four times larger and weigh more than a crow. Crows are smaller than pigeons, while ravens are larger than Red-tailed Hawks.

Ravens eat trash, rodents, lizards, insects, and more.©A-Z-Animals.com

What Is A Ravens Typical Diet?

A Common Raven eats anything it can get a hold of and will feast on insects, trash, carrion, seeds, fruit, and more. Its diet includes:

- Unmanaged picnics

- Trash

- Carcasses (mice and baby tortoises are examples)

- Lizards

- Frogs

- Nestlings from other birds

- Fish

- Meat (Raw or cooked)

- Fruit

- Seeds

- Carrion (Decaying Flesh)

- Insects

Ravens are scavengers by nature and eat a wide variety of food sources. These creatures prefer to devour decaying biomass, such as flesh or decomposing plant matter. Scavengers are vital in the food chain. Animal carcasses, or carrion, are kept out of an environment. Scavengers decompose organic matter and recycle it as nutrients back into the ecosystem.

What Are Ravens Favorite Food?

Ravens are known to eat oddities such as cat food, corn, eggs, and unsalted peanuts.©Michal Pesata/Shutterstock.com

Ravens certainly aren’t fussy eaters! Although, they do have some favorites, which include:

- Cat or dog food (small pellets)

- Corn

- Eggs

- Unsalted Peanuts and Nuts

- High Protein treats (insects, smaller animals)

- Fruits

- Vegetables

Regarding cat food, it may be a favorite of ravens, but raccoons also enjoy it. So, if you don’t want raccoons in your yard, you might want to avoid feeding this food!

So, if you don’t want raccoons in your yard, you might want to avoid feeding this food!

For the energy they need to forage, ravens prefer to eat protein as a food source. It doesn’t matter if an animal is sick or injured if they get to eat some meat!

Where Do Ravens Hunt for Food?

Throughout North America, ravens can be found in large swaths of Canada and the west coast of the US. While they’re most common in the northeastern Chesapeake region — particularly upstate New York and West Virginia — they’re also found in the western parts of Maryland and Virginia. They enjoy deciduous and evergreen forests up to the treetops, as well as seacoasts, high deserts, sagebrush, grasslands, and tundra. Their preferred winter habitat is a cadaver or rubbish pile.

They do well in rural areas, as well as in some towns and cities. Common Ravens benefit from the garbage, crops, irrigation, and roadkill they find when they live close to humans. While flying over open or partially open terrain, they wait until the ideal moment. If there is a food supply, a raven will find a way to get to it!

If there is a food supply, a raven will find a way to get to it!

How Do Ravens Hunt For Foods?

Common ravens are usually seen in couples or small groups, but vast numbers can develop at dumps and other food hotspots. They are intelligent and sometimes work together to flush out prey. Ravens mainly forage on the ground, but they will also raid other birds’ nests. Ravens can detect rotting carrion when flying over land. Their cries include a powerful croaking, often produced in flight.

Ravens are highly adaptable creatures. They can live in snow, desert, mountains, or woods. Common Ravens eat fish, meat, seeds, fruit, carrion, and rubbish. They are not above distracting other animals and stealing their food. Ravens have few predators and have been known to live up to 40 years in captivity! The raven is clearly a clever bird that will use any available resources to fulfill its needs.

Can You Feed A Raven?

Ravens are one of the only animals known to sue tools to feed©PhotocechCZ/Shutterstock. com

com

The raven has long been related to death and bad luck. A cursed soul reincarnated, according to the Germans. The Swedes thought a raven’s night croak was wicked. The Danish believed ravens were exorcised souls. Recent research on this unusual bird shows it is even more interesting than we thought!

Despite their dark historical and popular cultural image, a raven can be a friend. Ravens are trusting of people, often tolerating physical contact with them. The brave and playful Common Raven is always entertaining. On the ground, ravens strut and swagger. Ravens frequently perform aerobatics such as rapid rolls and wing-tucked dives!

Recent research shows the raven is as intellectual as dolphins and primates. For example, we now know that ravens can mimic human speech better than parrots. Common ravens are smart and can even solve problems together.

Just be wary of getting too close. A mother Raven is unrelenting when protecting her young. They are usually successful in thwarting potential threats. They also won’t wait to defend themselves. If they feel threatened, a Raven will lunge at predators using their large beak to attack!

They also won’t wait to defend themselves. If they feel threatened, a Raven will lunge at predators using their large beak to attack!

How to Feed A Raven

Food is by far the most effective technique for attracting ravens! First, make sure there is nothing around that could scare the raven away, such as larger animals or something resembling this. You can then start by leaving seeds or grains. This will keep it stink-free and less likely to attract other wild animals.

The key is to leave food out consistently, so the ravens get used to a feeding schedule and are more likely to stop by and eat. Leaving the food in a somewhat open area will make it easier for ravens to spot when flying overhead. By doing this, you are allowing the Raven to come to your food source, decreasing any chance of invading its space.

It is possible to gain a ravens trust this way and enjoy the reward of watching these curious creatures! Just remember, they are wild birds and should remain so. After all, this is part of their charm!

After all, this is part of their charm!

Up Next:

- Top 9 Largest Eagles in the World

- What Do Crows Eat? 15-Plus Foods They Love!

- The Top 9 Largest Flying Birds in the World By Wingspan

More from A-Z Animals

The Featured Image

Corvids, such as ravens, are one of the few animals that use tools regularly to obtain food.© iStock.com/Piotr Krzeslak

Share this post on:

About the Author

A substantial part of my life has been spent as a writer and artist, with great respect to observing nature with an analytical and metaphysical eye. Upon close investigation, the natural world exposes truths far beyond the obvious. For me, the source of all that we are is embodied in our planet; and the process of writing and creating art around this topic is an attempt to communicate its wonders.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Do Ravens Mate for Life?

Ravens are believed to mate for life and often stay in pairs in a specific area. Once they reach the age of puberty, ravens leave their parents’ nest and join the ranks of adolescent birds, much like humans! This group of juvenile birds eats, plays, and mates together until they find a mate and begin a new life together.

Once they reach the age of puberty, ravens leave their parents’ nest and join the ranks of adolescent birds, much like humans! This group of juvenile birds eats, plays, and mates together until they find a mate and begin a new life together.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Raising a Wild Baby Raven Right

Wild Galah, springtime, Melbourne, Australia.

Spring has sprung here in the Southern Hemisphere. In most bird homes, this means an influx of hormones and seasonal behaviours but surprisingly that’s not a problem I seem to be having this season with my own pet flock. Instead, spring seems to be making itself felt in the wildlife rescue part of my life. Gale force winds and bird’s nests don’t tend to get along! We’ve had our share of them with the change in season.

Last year, I wrote a post about a nesting pair of wild Australian ravens and what they could teach us about training birds. (Click here to read that. ) I was fascinated by the way they constructed lessons for their offspring and couldn’t quite believe my luck in getting to witness them.

) I was fascinated by the way they constructed lessons for their offspring and couldn’t quite believe my luck in getting to witness them.

Adult male raven (left) teaching its offspring (right) to fly and forage.

Their nest survived many sets of gale force winds, allowing them to successfully raise several clutches of offspring. In the winter months, a fat male Brushtail Possum took possession of the nest converting it into a possum drey. During the day you’d see his tail hanging over the edge, gently swaying in the breeze. That ended abruptly about a month ago.

You can see the end of the male Brushtail Possum’s tail hanging out of the lefthand side of the nest.

There’s no mistaking the sound of a fat male Brushtail coming home to its drey early one morning (pre-sunrise) to find 2 angry adult ravens have returned and repossessed their nest. The fights lasted for a couple of nights and you can probably guess who won? There’s no mistaking the sound of an overweight male Brushtail possum making a calculated retreat into your roof cavity, directly above the bed you’re trying to sleep in. (I’m allowed to make cracks about his weight because I’m the one that had to carry his heavy butt out of the roof cavity to his new possum box, after I fixed the broken roof tiles.)

(I’m allowed to make cracks about his weight because I’m the one that had to carry his heavy butt out of the roof cavity to his new possum box, after I fixed the broken roof tiles.)

The male Brushtail Possum. Told you he was fat!

So with a serious case of déjà vu I’ve been watching the raven lessons start up again. Awesome, right?

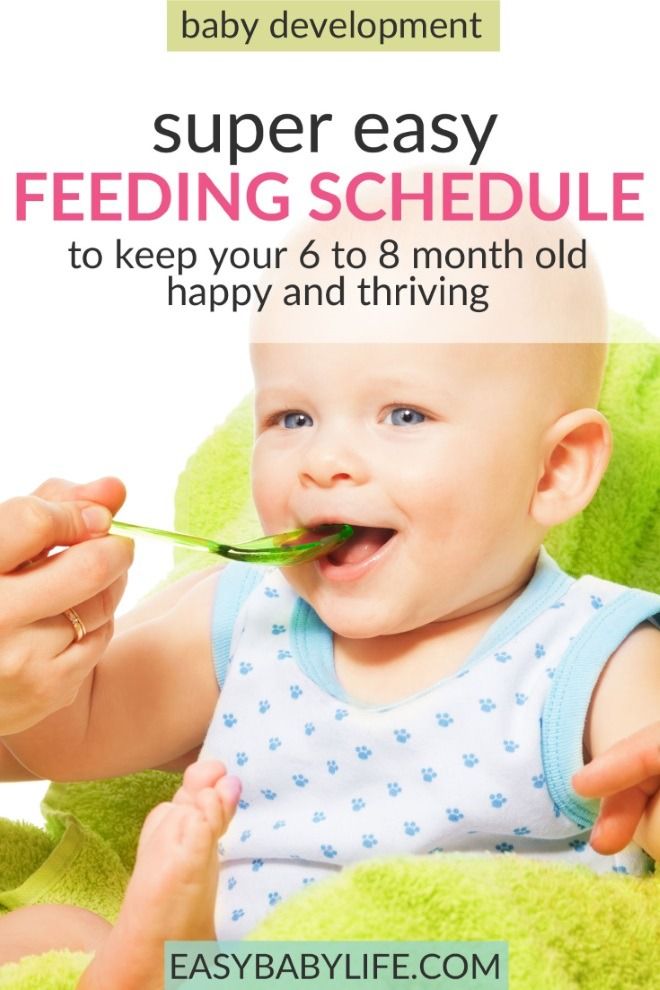

Well this brings me to the wildlife rescue side of things. About a week after some particularly strong winds, I was contacted about a baby raven that couldn’t fly. The woman who had found it, had rung a wildlife organization and was told to put it somewhere where its parents could find it but dogs and cats couldn’t. No parents showed up and so the raven wound up in her spare rabbit hutch at night, being released during the day. I was tagged in a post on Facebook, asking if I could help? Despite the worldwide nature of Facebook the bird wasn’t far from me, so I could.

Ready to go see an avian vet. Note the watery droppings? Not a good sign!

I went and assessed it. It really couldn’t fly (could only glide a little) and that worried me because at its age it should have been well and truly flying. I quickly checked it and found cuts under both wings, which might have stopped it from learning to fly, but shouldn’t be a permanent problem. It had mites and other signs of injury too, so I took it to my avian vet. It had a wound on its chest, another on its head, as well as multiple cuts under both wings. It also had scar tissue on one foot from an even older injury. It was underweight, with a body condition of maybe 1-2. Needless to say it required treatment for the above.

It really couldn’t fly (could only glide a little) and that worried me because at its age it should have been well and truly flying. I quickly checked it and found cuts under both wings, which might have stopped it from learning to fly, but shouldn’t be a permanent problem. It had mites and other signs of injury too, so I took it to my avian vet. It had a wound on its chest, another on its head, as well as multiple cuts under both wings. It also had scar tissue on one foot from an even older injury. It was underweight, with a body condition of maybe 1-2. Needless to say it required treatment for the above.

How to weigh a wild bird? Have the weight of your travel carrier recorded somewhere, so you can subtract it from the weight that includes the bird.

I don’t normally bring wildlife cases home unless there is some sort of mitigating circumstance. I’m a rescuer/transporter not a shelter. I have pets – and I’m not just talking about birds. It isn’t a great idea to mix domestic and wild together. You don’t want a wild animal watching dogs and cats interacting in a friendly way and learning to be less frightened of them as a result. Nor do I want to accidentally expose my pets to a disease a wild animal is carrying. This is why I choose to help wildlife through rescue/transport instead of as a foster carer. However, I am licensed and linked to shelter operators, so in an emergency (like when a shelter is overrun during bushfires) I will do foster care work and have fencing and enclosures on hand that I can put up as needed.

You don’t want a wild animal watching dogs and cats interacting in a friendly way and learning to be less frightened of them as a result. Nor do I want to accidentally expose my pets to a disease a wild animal is carrying. This is why I choose to help wildlife through rescue/transport instead of as a foster carer. However, I am licensed and linked to shelter operators, so in an emergency (like when a shelter is overrun during bushfires) I will do foster care work and have fencing and enclosures on hand that I can put up as needed.

On a corrected diet, the raven’s droppings quickly normalized.

It struck me that I might have found a different sort of mitigating circumstance. This baby raven was orphaned and injured. Possibly thrown from a nest in that last windstorm? Maybe it had been blown too far away for the parents to find it? Then it seems to have been attacked by a cat? But its injuries were surprisingly minor and weren’t the cause of it not thriving.

No, its main problem seemed to be lack of knowledge. It didn’t know how to ascend/descend or land. It had basic instincts allowing it to take off and glide but there was no control there. It also didn’t seem to know where to find food (or want to) and how to avoid cats. It had learned the terrible lesson that humans equal minced meat, making it way too tame for a wild bird. It was basically a few weeks behind where it should be in life skills with a few bad habits thrown in for fun. It struck me that it needed the raven lessons that I knew were going on at my home.

It didn’t know how to ascend/descend or land. It had basic instincts allowing it to take off and glide but there was no control there. It also didn’t seem to know where to find food (or want to) and how to avoid cats. It had learned the terrible lesson that humans equal minced meat, making it way too tame for a wild bird. It was basically a few weeks behind where it should be in life skills with a few bad habits thrown in for fun. It struck me that it needed the raven lessons that I knew were going on at my home.

Rebuilt and possum free. There are very young ravens in this nest.

Which left me with the question – would the ravens at home teach a baby that wasn’t their own how not to die? Well, why not? I knew from last year that their second and subsequent clutches of babies was placed to observe them teaching the previous clutch how to fly, etc. What if I set up an aviary where the baby raven could observe these lessons too? Even if my ravens had no interest in this raven, it would still be positioned to see them and maybe I could mimic the lessons myself while simultaneously dealing with its injuries and body condition? It was a plan.

With daylight fading, a smaller enclosure would allow the raven chick to familiarize itself with its environment for the night quickly.

By the time we got home from the vet’s on that first day, there was approximately an hour’s daylight left. So I decided night one would be spent in a crate, looking out at the spot where I would assemble the aviary the next day. I carefully selected a branch and foliage from a tree I knew my local ravens use during bad weather. It’s a safe, stable tree that provides great shelter. Familiarity with its foliage couldn’t hurt.

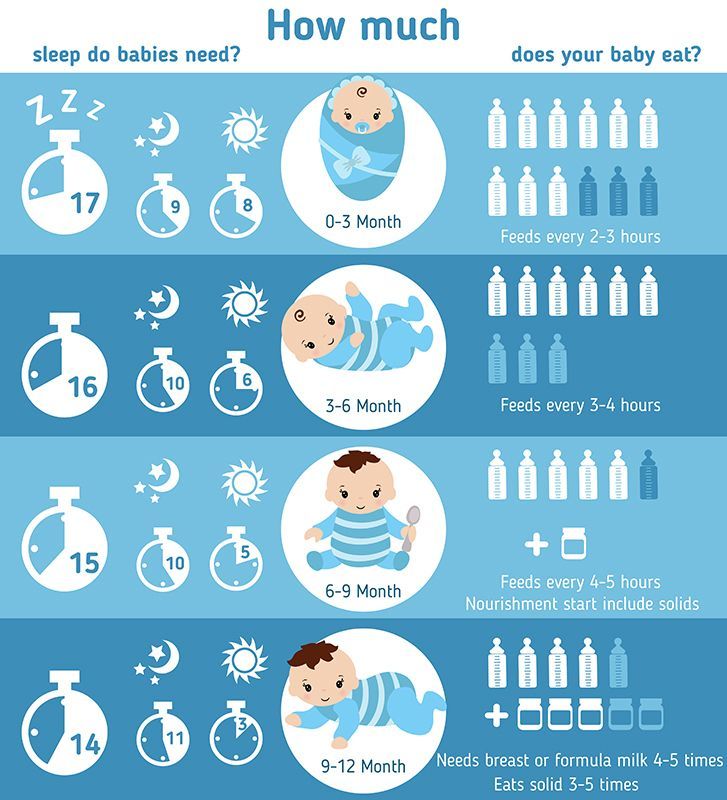

Preparing a foraging tray instead of a “food bowl”.

The first step was clearly to teach this bird that food bowls aren’t where food comes from and that food moves. I prepared a “foraging tray” that included samples of what this raven needed to learn to look at for food. So we’re talking different types of grass (roots, mud and all) that conveniently still had worms in them. Millipedes, beetles, woodlice/slaters – it turns out that my kitten’s love of hunting insects is handy. I followed her for 10 minutes and had a good collection of “creepies” (mum’s word not mine) to shove in this tray. Oh and that wailing sound? That’s my mother still screaming at me. She got just a little bit upset that I’m now keeping live insects in the fridge next to the milk. (It’s not my fault that mealworms go in to a state of torpor and therefore last longer in the fridge!!!)

I followed her for 10 minutes and had a good collection of “creepies” (mum’s word not mine) to shove in this tray. Oh and that wailing sound? That’s my mother still screaming at me. She got just a little bit upset that I’m now keeping live insects in the fridge next to the milk. (It’s not my fault that mealworms go in to a state of torpor and therefore last longer in the fridge!!!)

You can see one of the meal worms moving around on the bark in the centre.

Apart from the lovely “creepies” I was also mixing up a supplement called “insectivore” which is commonly used to raise this sort of bird. It smells bad and looks like mud but it does the job.

Getting ready to pounce on moving insects!

Success! Returning to the perch with a beak full of meal worm.

The next day I moved the chick out into the aviary in view of the adult ravens who were busily raising their own young. I added numerous foraging trays to the bottom of the aviary. Some were small stones, some were leaves and twigs, some were grass based. All common things this raven needed to learn to search through.

All common things this raven needed to learn to search through.

Hunting in the foraging trays. Overloaded with food to make it easy, but the raven seems to be getting the idea.

The adult ravens kept a close eye on what was going on, but generally left the chick alone. They proceeded to collect food and feed it to their own young. They didn’t feed the chick no matter how much it cried, but they were calling back and forth.

The adult female raven (close to nest) looks down at the chick in the aviary.

The male worried me because it came over and seemed to try to peck at the chick through the roof of the aviary, but it didn’t try that again. He seemed to increase his bug hunting which gave me hope for a while that he was going to feed the orphan, but he didn’t. (I’m 100% sure of this as I have surveillance cameras and checked the footage.)

The adult male raven has approached the baby several times and seems to have stepped up the food hunt – hunting bugs here.

The main challenge turned out to be getting the chick to descend to forage. It was quite happy (if a little clumsy) in its attempts to get to the highest perch but once there, it refused to jump down more than one or two branches. It was as though it reached some sort of fear threshold and would just freeze. I carefully arranged the branches to be similar to a tree, but easy enough to jump from one to another. I didn’t want to handle the bird much (better if it has a healthy fear of humans) but occasionally put it down the bottom of the aviary to forage and work its way up its “tree” in the vague hope that if it learned how to go up confidently, following the reverse path might become less frightening. This had limited success. The chick agreed to go down one more perch but no further.

Well the answer to this was to start some flight training. The aviary it was in, is on wheels and so easy enough to move into my outdoor patio. Fishing nets formed walls, turning it into a temporary flight. I set it up similar to how the wild ravens do. They start their babies off with horizontal flights from a tree to a rooftop. I was placing mealworms on my outdoor table (so no more than a metre drop from the aviary’s top perch). From this he’d fly to the ground. When done with training exercises, I’d move the aviary back to in view of the wild ravens lessons. They were small steps, but enough to build the bird’s confidence so he started ascending and descending within the aviary on his own.

I set it up similar to how the wild ravens do. They start their babies off with horizontal flights from a tree to a rooftop. I was placing mealworms on my outdoor table (so no more than a metre drop from the aviary’s top perch). From this he’d fly to the ground. When done with training exercises, I’d move the aviary back to in view of the wild ravens lessons. They were small steps, but enough to build the bird’s confidence so he started ascending and descending within the aviary on his own.

Wet after a bath, the chick climbed back up to dry off.

The other thing that happened was the raven had a bath, washing off the last of the dried blood under its wings. It also preened out some broken feathers. The next day, it had a weight drop and I wasn’t sure if there was an underlying disease or if it was due to the dried blood and feathers being removed? I’d know in 24 hrs. The bird desperately needed to put on weight, so I found myself looking to the wild ravens for an idea.

Imitating the way the parent ravens hide food in gutters, I filled a food bowl with mud and leaves, with food inside it. “Insectivore” (a rearing food) looks like mud, so that’s in there too.

It seems wild ravens like to fill people’s guttering with mud, hide worms and other creepies in them and get their babies to hunt them out… Well I didn’t have any spare guttering lying around but I did have a long plastic hook-on food bowl, mud and plenty of creepies. Combine that with a bird that wants to be up high – it couldn’t hurt. Fortunately the additional food seemed to help. Within 24 hrs its weight had significantly risen.

Naturally, there had to be another hiccup in my plans. Namely gale force winds. With a severe weather warning in place for my area, I wasn’t comfortable in leaving a solitary baby bird outside in an aviary overnight. I decided to bring it in to the crate to sleep out the storm. As daylight faded, I reached in and grabbed the baby. By now it had a healthy fear of humans. (I hadn’t handled it more than necessary.) It started screaming a distress call. The next thing I knew the wild parent ravens were on me. Both of them were swooping me, using their beaks as large stabbing sticks on each swoop. I had no choice but to put the baby back down in the aviary and make a run for it. If they were protecting the baby, I wasn’t willing to break that new-formed bond.

(I hadn’t handled it more than necessary.) It started screaming a distress call. The next thing I knew the wild parent ravens were on me. Both of them were swooping me, using their beaks as large stabbing sticks on each swoop. I had no choice but to put the baby back down in the aviary and make a run for it. If they were protecting the baby, I wasn’t willing to break that new-formed bond.

It’s blurry because… well seriously would you stand still with 2 of them trying to kill you?

I came back after dark and took the baby to safety then. Carefully holding its beak closed to stop the distress call so the parents didn’t hear me. This meant it safely rode out the storm in the crate inside. Meanwhile I woke up to some seriously mad wild ravens screaming their heads off just outside my bedroom window at dawn. I quickly weighed the baby and got it back out there.

I had a decision to make. The baby’s weight had continued to rise, but it was still 5g below what I had set as a releasable goal. The weather forecast for the day was great, low wind, not too hot, not too cold. Rain and wind predicted for the next day – which wouldn’t be ideal for a new release to learn to fly in, but wonderful for a recent release that is looking for water. More importantly, it was fast reaching an age when parents would be less likely to look after it. I had parents acting like they wanted to adopt it. If there was any chance they would and that delaying release to wait for more weight could stop them… I knew this baby stood a better chance of survival if it had a community of its own kind behind it. The decision seemed obvious.

The weather forecast for the day was great, low wind, not too hot, not too cold. Rain and wind predicted for the next day – which wouldn’t be ideal for a new release to learn to fly in, but wonderful for a recent release that is looking for water. More importantly, it was fast reaching an age when parents would be less likely to look after it. I had parents acting like they wanted to adopt it. If there was any chance they would and that delaying release to wait for more weight could stop them… I knew this baby stood a better chance of survival if it had a community of its own kind behind it. The decision seemed obvious.

I opened the door and waited.

I fed it, gave it a chance to eat and digest the food, opened the door and waited. For 10 minutes it continued to move around the aviary, looking at the open door. Then the adult male flew overhead, landed behind me and emitted one loud CAW.

The baby flew out and landed within a few metres of me. The adult male swooped down and quickly fed it. A technique I’d seen it use on its own offspring, when rewarding flight.

A technique I’d seen it use on its own offspring, when rewarding flight.

Near me but this chick is focused on the adult male.

In that split second, I knew it was going to be ok. I also knew that I had to get out of the way before the adult decided I had to die again. He obviously wasn’t keen on me at the moment and if ever there was a death stare…

Ready to swoop in and feed the chick.

He called the baby up to the fence with him, but the baby wasn’t so great at flying yet and wound up flying to a nearby roof.

The orphan raven in flight.

From there, he coaxed it to fly to a nearby eucalyptus tree (in view of the nest where the adult female was guarding the nest bound chicks), fed it and left it while he disappeared in search of food.

Led to a Eucalyptus tree by the male, the chick stayed put (well-hidden but in sight of the nest).

The chick stayed put for well over an hour and the adult female kept emerging from the nest to check it.

Double guard duty. An eye on the nest and an eye on the orphan.

Then suddenly the baby flew off and landed in a neighbour’s hedge. I could hear a small dog going absolutely nuts and looked around for the parent ravens. They were nowhere near. The chick had traveled over 500metres and it occurred to me that they hadn’t been watching it to know it had done that.

I walked down the street to check it out. I found the baby stuck on a shed roof, with two yipping dogs below it. It clearly didn’t know where to go or what to do. I got a net and got up on the roof. (Met a neighbour I’d never seen before, “Why are you on my roof?” is a real icebreaker.) I got within a metre of the baby when the adult male appeared and wow was he displeased to see me! I’m pretty sure that was a very rude word in raven. He took the baby off with him to a safe tree. I realized then, that the adoption really had happened. It wasn’t my imagination. These ravens were going to fight to the death for this chick.

Apparently this is where the best worms are? This is the Chick hunting.

A few hours later, they were back in my neighbour’s garden, where the ravens like to collect worms. The chick was on the ground foraging. The male was on the roof above, ready to swoop.

You’ve got to give it to him, he’s got great parenting skills. The chick is just below him.

It seemed the male raven was in full lesson mode, taking the chick from one location to another. The chick wasn’t just watching the ravens search for food either. A local blackbird, kept dropping in and snatching worms and flying off too.

They might be a pest here, but observing this little one was helpful for the orphan.

I knew that around 5pm every night, all of the local ravens tend to meet up and fly around the neighbourhood together for at least 10minutes. I was waiting with bated breath in hopes of seeing something like this:

My local flock of ravens flies up to join those distant specks almost every night (every raven in the entire area joins up for about 10mins).

However, it got really windy, so instead I found the adult male, chick and the last clutch of juveniles some distance away in a tree. They were only small specks in the tallest tree but you could pick the baby apart from the others due to its inability to land properly (kept falling off tree branches and clumsily landing on another). The adult male also kept zipping back to the nest from that tree. (Apparently ravens can spot pesky attacking miner birds from some distance.)

Not easy to see. You’re looking at approximately 5 black specks in the tallest tree. 3 of them are on the left hand branches.

As night quickly fell I could hear the anxiety in the adult male’s calls as he tried to extricate the chick from that tree. Eventually he managed it though. The female climbed into the nest (presumably to keep younger chicks warm) and the adult male and adopted chick, settled within a metre of the nest.

It’s dark, but I’ve over-exposed this shot so you can see where they all are for the night.

Having come to know these birds unbelievably well in the last few years, I think I can safely say that the baby is going to make it to an adult now that it has help from its own kind. When a rescue goes this well – it’s a dream scenario. If the raven hadn’t met a human with a spare rabbit hutch, I don’t think it would have made it. It takes one moment of compassion to start a chain of events that can make a real difference to an animal’s life.

I was expecting to end this post here, but I know that some of the locals who have been following this story on Facebook are going to be worried after yesterday. The bit of wind and showers that were predicted? We got hit by a really full-on storm. Trees are down. Power has been out. My yard isn’t pretty. Huge ceramic pots that I can’t even lift have been picked up by the wind and hurled at the house. I was out on a different rescue during the storm, avoiding flying sofas with my car. I came home and checked on the ravens and there weren’t any around to check. I’m not just referring to the orphan and adoptive parents – I’m saying the local flock of 40 was gone. It wasn’t just the ravens either. The blackbird was missing, the local dove flock was gone, no sign of my resident king parrots, corollas, or galahs either. It was eerily silent. They came back the morning after the storm. I believe the chick is still with the other young ravens as there are still “feed me” calls coming from their eucalyptus tree a few streets away and the adult male visits the nest and then heads back there.

I’m not just referring to the orphan and adoptive parents – I’m saying the local flock of 40 was gone. It wasn’t just the ravens either. The blackbird was missing, the local dove flock was gone, no sign of my resident king parrots, corollas, or galahs either. It was eerily silent. They came back the morning after the storm. I believe the chick is still with the other young ravens as there are still “feed me” calls coming from their eucalyptus tree a few streets away and the adult male visits the nest and then heads back there.

The nest survived the storm but the tree is damaged and vacant.

There was one exception. I kept an eye out and saw the adult male silently flying in as darkness fell. He was checking the nest which had survived the storm. The female was still in it with the nest bound chicks. From the sounds – he fed her and left. He flew off into the distance, further than I could see and he didn’t come back again that night. None of them did. Wherever the orphan chick was, I was confident that the adult male was spending the night with it and likely the rest of the local ravens too. He wouldn’t stay away from his own nest for any other reason. It seems the wild birds knew this area was going to be hit badly and had flown to a safer place to ride out the storm, but it was already getting dark when the storm ended so they stayed away for the night.

He wouldn’t stay away from his own nest for any other reason. It seems the wild birds knew this area was going to be hit badly and had flown to a safer place to ride out the storm, but it was already getting dark when the storm ended so they stayed away for the night.

The morning after the storm. The female’s tail is visible on the left, the male’s on the right and the babies are noisy. The male flew off from here to where I could hear an older baby bird calling.

I’ve spent a lot time in university lectures listening to biologists tell me that an animal’s sole purpose/aim in life is to reproduce and pass on its own genetic material. Then in the real world, I meet a pair of ravens who willingly share their own babies’ food with an orphan. They’re even willing to leave their own young in order to protect the orphan. I can’t help but think we as humans underestimate the other animals around us.

If you find a baby bird and want to help it, click here for a post that will help you with that.

Mel Vincent lives in Melbourne, Australia and is a wildlife rescuer, vet student and animal trainer.

Tags: Australian raven, baby bird, bird, bird rehabilitation, chick, Diet Health and Nutrition, feeding ravens, feeding wild birds, flight training, Housing Environment and Cages, mel, mel vincent, orphaned bird, Outdoor Free Flight Training, Parrot Behavior, Parrot Training, raising a bird, raising a chick, raven, releasing wildlife, Socializing and Interaction, storm birds, vincent, wild bird rescue, wild rescue, Wildlife Rescue

What is the right way to feed a crow chick? And a chick?

Headings: Corvids

Somewhere God sent a piece of cheese to a crow

How to properly feed a crow and a crow chick?

With all due respect to Ivan Andreevich Krylov, it is worth noting that his fable made a significant contribution to ornithology, but, unfortunately, not a positive one. After all, people now, as they see a crow, strive to treat it with cheese, which a hungry bird enjoys eating. So can crows be fed cheese? And how to properly feed a bird that, by chance, got into trouble and ended up under the care of people. The main principle - do no harm, here we are talking about the same. Based on our practice, feeding birds with foods high in fat causes serious pathologies of internal organs - hepatitis, fatty liver, pancreatitis, coronary artery disease, cholecystitis, cancer, immunodeficiencies, arthritis, arthrosis. Getting this set of chronic diseases is difficult to restore the health of the bird again. And what can we say about the flight, where you need lightness and a healthy heart, not to mention the joints. Let's figure out how to properly feed the corvids. We remind you that the corvid or raven family includes not only the gray crow, but also the black crow, jackdaw, rook, common raven, magpie, kuksha, common and blue jay.

After all, people now, as they see a crow, strive to treat it with cheese, which a hungry bird enjoys eating. So can crows be fed cheese? And how to properly feed a bird that, by chance, got into trouble and ended up under the care of people. The main principle - do no harm, here we are talking about the same. Based on our practice, feeding birds with foods high in fat causes serious pathologies of internal organs - hepatitis, fatty liver, pancreatitis, coronary artery disease, cholecystitis, cancer, immunodeficiencies, arthritis, arthrosis. Getting this set of chronic diseases is difficult to restore the health of the bird again. And what can we say about the flight, where you need lightness and a healthy heart, not to mention the joints. Let's figure out how to properly feed the corvids. We remind you that the corvid or raven family includes not only the gray crow, but also the black crow, jackdaw, rook, common raven, magpie, kuksha, common and blue jay.

What can be given to ravens and corvids? Proper diet.

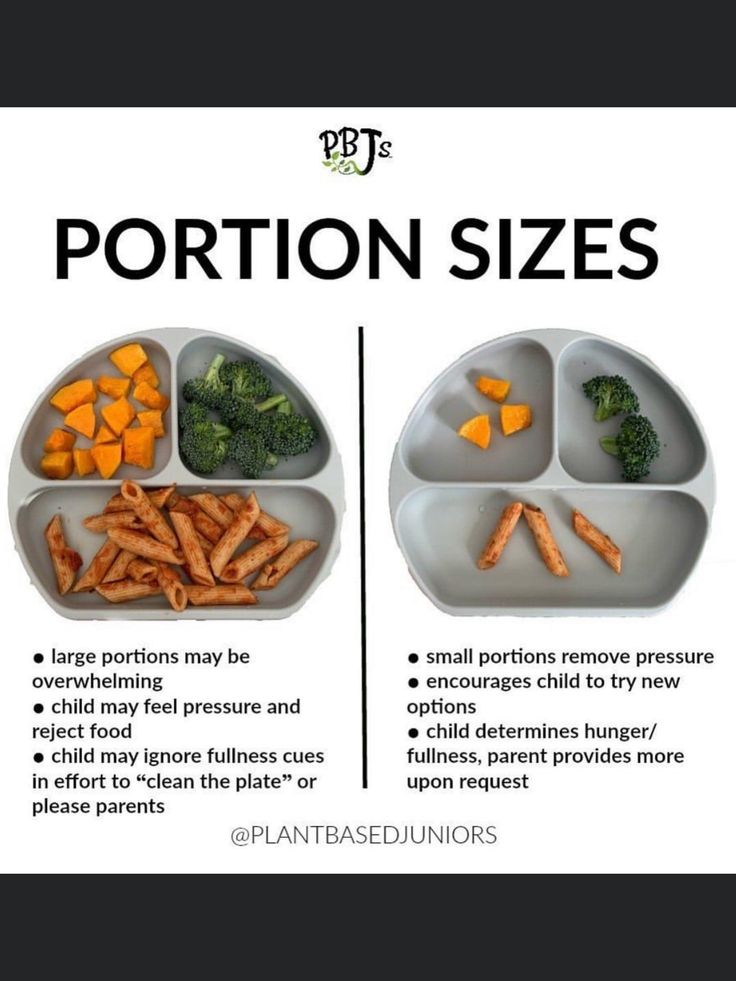

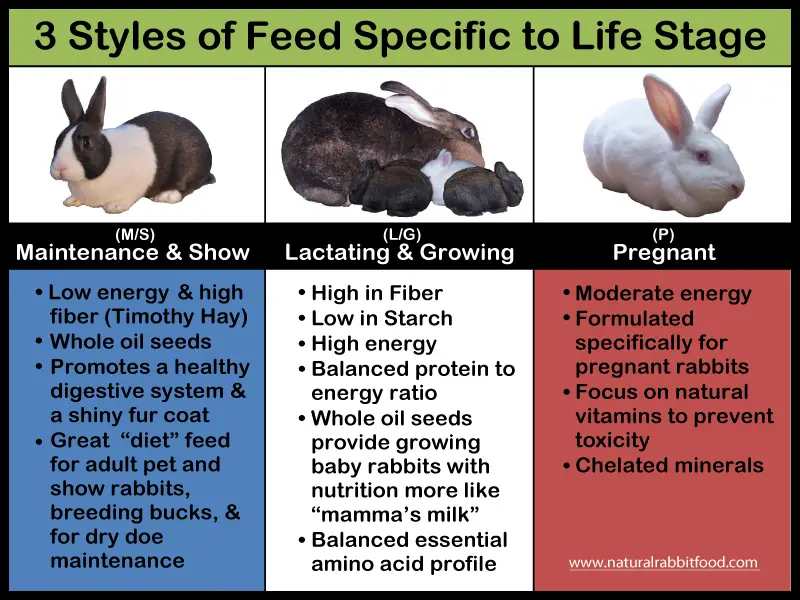

The basis of the diet of these birds is:

- lean meats - beef, turkey, chicken.

- from offal, corvids can be given chicken hearts, stomachs, heads, necks (feeding chicken heads and necks refers to crows, crows and rooks, sometimes jackdaws and jays also love such products very much).

- the diet of corvids also includes fat-free cottage cheese,

- boiled river fish (it is undesirable to feed it raw because of the risk of infecting the bird with helminthiases, for the same reason it is impossible to feed earthworms to corvids, as this can cause the development of a serious disease in birds - syngamosis).

The diet of the crow contains more meat than the diet of other corvids. And best of all, if the thawed mice and day-old chickens prevail in the diet of the crow, and not just meat and offal.

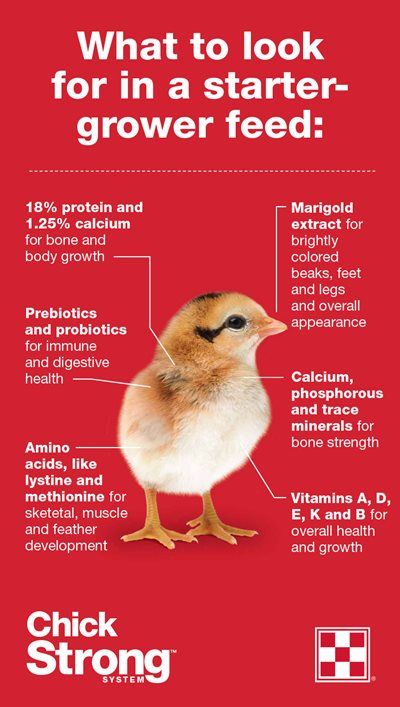

As obligatory top dressing, the corvids need insects in the diet:

- flour worm

- crickets

- locust

- ant eggs

These birds are fed in nature, and our task is to bring the conditions of keeping and feeding birds closer to their natural ones. Therefore, treat your corvid pet not only with meat, but also with insects, berries, fruits, and vegetables. Berries, vegetables and fruits can be given any, you just need to be sure that they are not treated with insecticides.

Therefore, treat your corvid pet not only with meat, but also with insects, berries, fruits, and vegetables. Berries, vegetables and fruits can be given any, you just need to be sure that they are not treated with insecticides.

As a supplement, corvids can be fed boiled eggs, but in small quantities.

You can also give boiled buckwheat, rice, millet, corn grits. But, of course, the main percentage in the diet is still occupied by meat.

Birds can be offered dried bread, white bread crackers, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, gammarus as treats. As a mineral supplement for birds, egg shells can be ground into powder and placed in a separate feeder.

What should never be given to birds?

Now let's designate what exactly cannot be given to birds.

The list of prohibited products includes:

- salty, fatty, sweet, fried foods,

- sausages,

- milk,

- bread,

- canned food,

- alcohol,

- crackers,

- chips,

- juices,

- peanuts (here we mean the whole list of what is harmful to humans),

- citrus fruits (there is little information about this, someone feeds birds citrus fruits for a long time and this does not cause any pathologies, and in some birds, taking citrus fruits causes severe allergic reactions).

Now about vitamins. If the bird is provided with a complete diet, which includes insects and mineral supplements, then the need for vitamins is reduced to a minimum. But still, we recommend fortification twice a year - in early spring and late autumn, that is, in courses of 2 weeks. From well-proven vitamins, German Beaphar Mauser Tropfen, Lebensvitamine can be used, from domestic ones - Chiktonik. A complete, well-balanced diet is the basis of the health of any living being.

Veterinary ornithologist of the bird hospital "Green Parrot" Pavlova E.A.

Author: petitabeille | Date: 08/14/2016 - 12:56

If the chick is sitting on the ground, it is not a fact that he has a problem.

At the sight of a chick sitting on the ground, which not only can fly, but can't really run, many of us naturally turn on the "pity and compassion" reflex. How small, helpless, and there are so many dangers around! It seems that the cub got into trouble, "fell out of the nest", and if he is not helped, he will inevitably die. And now they bring the chick home, try (more or less competently) to feed it, hardly imagining what to do with the bird or vaguely hoping to "grow up and release it."

And now they bring the chick home, try (more or less competently) to feed it, hardly imagining what to do with the bird or vaguely hoping to "grow up and release it."

In the meantime, he's probably fine. In May-June, grown crows, jackdaws, magpies, etc. in droves fly out, or rather, fall out of their nests. Fledgling chicks still do not know how to fly, or independently get their own food, or generally take any distinct care of themselves. Parents take care of them, feed, water, and most importantly - teach everything that a wild bird should be able to do. In highly organized birds like corvids, there are not so many instincts, and therefore a parental example is a thing necessary for adaptation to independent living. Training continues for quite a long time, you can often see how one crow feeds another, which practically does not differ in appearance and size: even standing on the wing, fledglings continue to depend on their parents for some time.

This is perhaps the most difficult period in a bird's life - yet parents are not always able to protect the little ones, despite all the miracles of dedication that they sometimes show. Quite a large percentage of fledglings die - at the hands of people or in the teeth of dogs and cats. But! Every single adult bird has passed this stage. This is a normal, absolutely natural course of things.

Quite a large percentage of fledglings die - at the hands of people or in the teeth of dogs and cats. But! Every single adult bird has passed this stage. This is a normal, absolutely natural course of things.

The moral of this fable is this: if you find such a chick, don't touch it. Do not pick up, do not bring home, do not try to feed yourself. Firstly, it is not so easy to fully feed and raise a wild bird. Secondly, if you take care to learn how to properly feed her, if you provide her with proper care, if she survives with you, know that you will not be able to return her to nature. Captive-bred chicks often don't even learn to fly, for lack of an example, not to mention more complex skills like hunting. But they firmly learn that food must be obtained from the hands of people, and water from a drinking bowl. By releasing such a chick into the wild, you condemn him to an absolutely inevitable death - either quick, violent, or slow - from hunger.

Of course, a crippled fledgling initially has no chance of surviving on the street.