When does a baby start to eat semi solid food

Introducing Solid Foods to Infants - 9.358

Print this fact sheet

by L. Bellows, A. Clark, and R. Moore* (10/13)

Quick Facts…

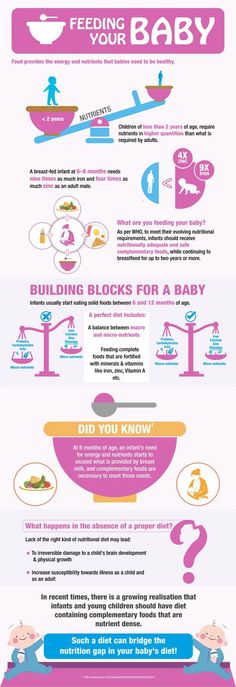

- During the first year of life, breast milk or an iron-fortified formula provides all the nutrients an infant needs for healthy growth and development.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends introducing solid foods along with breast milk or formula, preferably at 6 months of age. Single-ingredient foods should be introduced one at a time at weekly intervals.

- Ultimately, an infant’s developmental readiness should determine when to feed solid foods.

- Avoid offering your infant sweetened foods since they can promote tooth decay, excess calories, and weight gain.

- Never force-feed bottles or food as this may cause a baby to ignore what his or her body says, which can ultimately lead to poor eating habits later in life.

The introduction of semi-solid and solid foods to an infant’s diet can be confusing and complicated for many parents. There is even some disagreement among the leading health authorities regarding when to incorporate new foods and which foods to include. Essentially, the exact order of food introduction does not matter for many babies. The most important factor is which foods to introduce at each age, and the child’s relationship with these foods. During the first 6 months of life, breast milk is capable of supplying all of the nutrition an infant needs and also provides protection against illness. Most experts agree that solid foods should be incorporated around the first 6 months of life, beginning with single-grain cereals followed by fruits, vegetables, and proteins in later months. Ultimately, an infant’s developmental readiness should determine when to introduce semi-solid foods to the diet.

Starting Solid Foods Too Early

There are many misconceptions that come along with the decision to feed an infant solid foods before 6 months of age- a common belief being that feeding solid foods such as cereal will make an infant sleep through the night. In reality however, sleeping through the night is actually associated with mental development, not the fullness of an infant. Feeding an infant solid foods before 6 months may increase the risk of choking, food allergies, gastric discomfort, and becoming overweight or obese later in life.

In reality however, sleeping through the night is actually associated with mental development, not the fullness of an infant. Feeding an infant solid foods before 6 months may increase the risk of choking, food allergies, gastric discomfort, and becoming overweight or obese later in life.

Waiting Too Long to Start Solid Foods

Introducing solid foods after 9 months may result in an infant who is resistant to trying solid foods, and may have difficulty chewing. Beyond 9 months of age, it is important to incorporate an external source of iron, since an infant’s iron stores will gradually become depleted.

When to Start

The child’s age, appetite, and growth rate are all factors that help determine when to feed solid foods. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), semi-solid foods are a significant change and should not be introduced until 6 months of age. This age usually coincides with the neuromuscular development necessary to eat solid foods. Fruit juice is not recommended until 7 months of age, and should be limited to 4-6 ounces per day. It is important to note that although only 100% fruit juice is acceptable at this age, it is not recommended.

It is important to note that although only 100% fruit juice is acceptable at this age, it is not recommended.

Before feeding solid foods, the baby should be able to:

- Swallow and digest semi-solid foods.

- Sit up well, an important step in order to be able to stay seated in a high chair to feed.

- Maintain neck and head control while seated, a necessity in order to turn his or her head to signal when he is finished eating.

- Be able to open his or her mouth and move the tongue and lips well, allowing the movement of food around the mouth.

- Demonstrate an interest in food and eating solid foods.

Starting Solid Foods

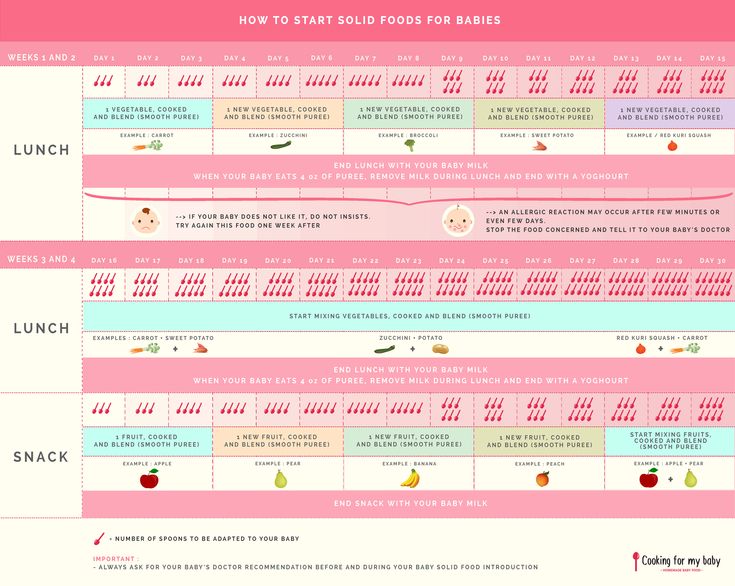

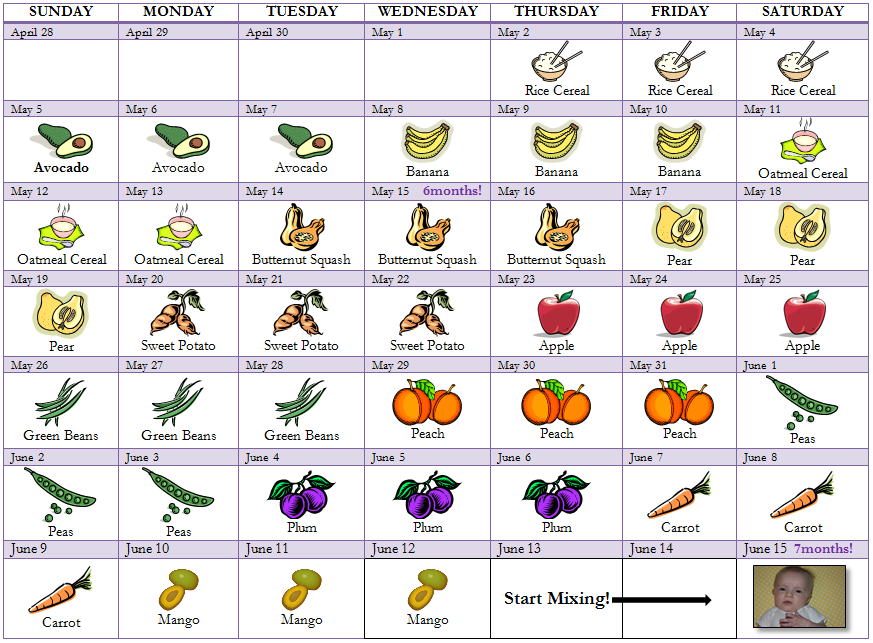

During the first feeding, many parents find it beneficial to offer semi-solid foods after breast or formula feeding, when the infant may be more likely to experiment with new foods. The sequence of new foods is not critical, but iron-fortified rice cereal mixed with breast milk or formula is a good first choice. In the beginning, it may be best to introduce single-ingredient foods one at a time at weekly intervals. This process helps identify any food sensitivities the child might have. Gradually add vegetables, fruits, and meats to the infant’s diet one at a time. Serving mixed foods is not recommended in the beginning.

In the beginning, it may be best to introduce single-ingredient foods one at a time at weekly intervals. This process helps identify any food sensitivities the child might have. Gradually add vegetables, fruits, and meats to the infant’s diet one at a time. Serving mixed foods is not recommended in the beginning.

Important Tips:

- Prepare for feeding with a baby spoon (plastic is best), bib, and an infant seat or high chair. Using the baby spoon, place a small amount of food, about 1/2 teaspoon, on the baby’s tongue. Never use a bottle or other feeding device for feeding semi-solid food.

- Begin with single-ingredient foods, such as iron-fortified rice cereal. Wait five days between introducing new foods so that any allergies or intolerances to these new foods can be identified.

- Feed the baby when he or she is hungry, but do not overfeed. Look for signals that the feeding is finished such as shaking the head.

- Make meal time a happy time, usually morning or midday is the best time for offering feeding new foods.

- Never force your child to finish bottles or food. This can cause the baby to ignore what his or her body says and may lead to poor eating habits later. Watch for body language cues.

- Never leave your child alone while eating.

Foods for the First Year

Breast milk or infant formula—In addition to incorporating new foods, it is also best to supplement a child’s diet with breast milk or infant formula to ensure adequate nutrition. This can be accomplished through the addition of breast milk or formula to solid foods.

During the first year of life infants are not ready for milk products from animals (such as cow or goat milk).

Grain Products—Simple grains such as rice cereal are a good first choice for introducing solid foods to an infant. Grains offer additional iron needed for proper growth and development. Introduce wheat products last, since they are more allergenic.

Fruit—Choose plain, ripe, or pureed fruit such as applesauce, peaches or mashed bananas. Combine the fruit with breast milk or infant formula, and puree. Steer clear of citrus fruits during the first year of life due to their high acidity, and avoid fruit desserts that contain unnecessary sugar. Desserts provide unneeded, excess calories and may lead to overweight and obesity. Fruit juices that are 100% may be introduced at 7 months when the baby learns to drink from a cup. It is important to dilute 100% fruit juice half and half with water or strain the pulp before giving to a baby. Avoid sweet drinks, such as soda, tea, and sports drinks as they can promote tooth decay and lead to unnecessary calories.

Combine the fruit with breast milk or infant formula, and puree. Steer clear of citrus fruits during the first year of life due to their high acidity, and avoid fruit desserts that contain unnecessary sugar. Desserts provide unneeded, excess calories and may lead to overweight and obesity. Fruit juices that are 100% may be introduced at 7 months when the baby learns to drink from a cup. It is important to dilute 100% fruit juice half and half with water or strain the pulp before giving to a baby. Avoid sweet drinks, such as soda, tea, and sports drinks as they can promote tooth decay and lead to unnecessary calories.

Vegetables—Puree vegetables with breast milk or infant formula in a manner similar to fruits. Do not add salt to vegetables as this may cause strain on an infant’s kidneys.

Protein—Puree proteins such as chicken, beef, pork, tofu, or beans with breast milk or infant formula, similar to fruit and vegetable preparation.

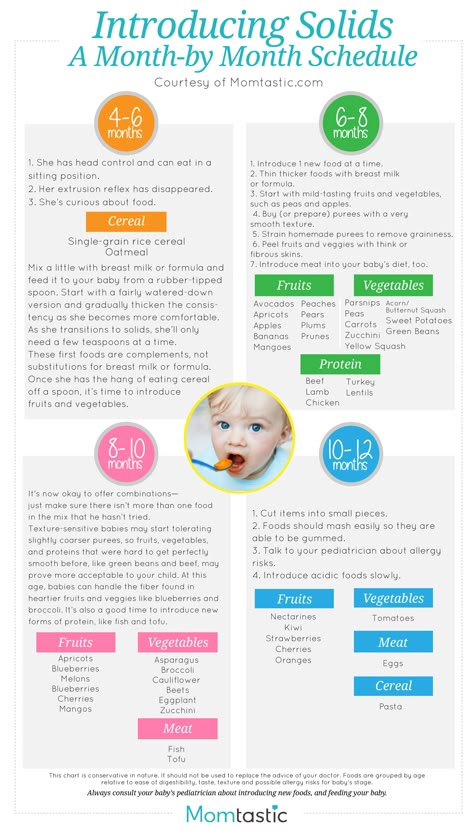

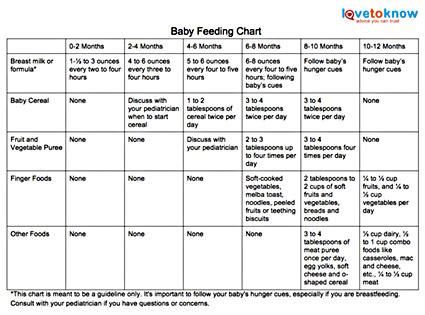

See Tables 1 and 2 for more information on introducing foods during the first year.

Foods to Avoid During the First Year

Risk for allergic reaction—nuts and nut products, egg whites, and shellfish.

Choking Risk—celery, grapes, candy, carrots (raw), corn, raisins, cherry tomatoes, nuts, olives, popcorn, peanut butter, sausage, hotdogs, and gum.

Additional foods to avoid—Honey (due to hazardous botulism spores), cow’s milk (harmful to an infant’s kidneys), rare meat, cheese (due to contamination with harmful bacteria), unpasteurized juice, bean sprouts, and alfalfa sprouts.

Table 1. Calendar for feeding your baby for the first year of life.*

| Foods | Birth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 months |

| Breast milk or iron-fortified formula | Breast milk or formula | Continue breast milk or iron-fortified formula | Start whole cow’s milk from cup. | ||||||||||

| Cereals and grain products | Iron-fortified cereals (rice, barley, oats.) Iron-fortified plain infant cereal (no fruit flavor or mixed grains). Start with rice. | Mixed-grain, iron-fortified cereals. Spiral pasta, teething crackers, rice. Bread and toast strips. | |||||||||||

| Vegetables | Pureed, single vegetables such as sweet potatoes, or squash. | Cooked vegetables mashed or chopped. | Bite-size, soft, cooked vegetables for finger-feeding. | ||||||||||

| Fruit & fruit juices | Pureed, single fruits such as bananas, peaches, pears, or apples. | Cooked, canned, or soft fresh fruits, mashed or chopped. | Sliced soft fruit for finger feeding. | ||||||||||

| Meat, dairy, and other protein foods | Pureed single meats such as chicken, pork, or beef. Pureed tofu, and beans. Pureed tofu, and beans. | Same foods, pureed or mashed beans. Cottage cheese, soft pasteurized cheese, and yogurt may also be introduced. | Same foods, bite-sized pieces for finger feeding. | ||||||||||

| Egg and fish | Egg, and boneless fish. | ||||||||||||

| *SPECIAL NOTE: Some foods may cause choking. Because of this, avoid raw carrots, nuts, seeds, raisins, grapes, popcorn and pieces of hot dogs during baby’s first year. | |||||||||||||

Table 2. Infant serving sizes based on age.*

| Age | 6 months | 6-8 months | 8-10 months | 10-12 months |

| Serving Size | Mix with 1 teaspoon of pureed cereal, fruit, or vegetable and 4-5 teaspoons of breast milk or formula to begin with. Increase to 1 tablespoon of pureed cereal, fruit, or vegetable mixed with breast milk or formula, two times a day. Gradually thicken the consistency of the pureed foods. Increase to 1 tablespoon of pureed cereal, fruit, or vegetable mixed with breast milk or formula, two times a day. Gradually thicken the consistency of the pureed foods. | Feed 3-9 tablespoons of cereal, in 2-3 feedings. When feeding fruits and vegetables, start with 1 teaspoon, and gradually increase to ¼ to ½ cup in 2-3 feedings. | Dairy: 1/4-1/3 cup, 1/2 ounces of cheese. Iron-fortified cereal: 1/4-1/2 cup. Fruit: 1/4-1/2 cup. Vegetables: 1/4-1/2 cup. Protein: 1/8-1/4 cup. | Dairy: 1/3 cup, 1/2 ounces of cheese. Iron-fortified cereal: 1/4-1/2 cup. Fruit: 1/4-1/2 cup. Vegetables: 1/4-1/2 cup. Combo foods (such as macaroni and cheese, or casseroles): 1/8-1/4 cup. Protein foods: 1/8-1/4 cup. |

| *It is important to not feel bound to these serving size guidelines, as they are only estimates. Infants may naturally consume more or less than these amounts. | ||||

Summary

- Offer new foods when your baby is in a good mood- not too tired and not too hungry.

- Serve solids after your baby has had a little breast milk or formula.

- Give your baby time to learn to swallow these foods and get used to the new tastes and textures. Be flexible with how your child experiences new foods (touching the food, exploring its texture, etc.).

- Do not feed your baby directly from the jar; use a clean dish. Heat only the amount baby will eat, starting with half of a teaspoon, and throw any leftovers away.

- Make meal time fun for your infant.

- Infants have a natural sense of fullness, it is important never to overfeed or force-feed your infant. Doing so will lead an infant to disregard its sense of fullness, which can lead to eating disorders or obesity later in life.

- Never add salt or sugar to foods to make them more appealing for your infant.

Additional Resources

American Academy of Pediatrics: www.healthychildren.org

References

American Academy of Pediatrics: Switching to Solid Foods. 2012. www.healthychildren.org.

2012. www.healthychildren.org.

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Introducing solid foods to toddlers. 2012. www.eatright.org.

Douglas, Ann. Mealtime Solutions for Your Baby, Toddler, and Preschooler: The Ultimate No-Worry Approach for Each Age and Stage. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008.

*L. Bellows, Colorado State University Extension food and nutrition specialist and assistant professor; A. Clark, University of Northern Colorado associate professor; and R.Moore, graduate student. 12/98. Revised 10/13.

Colorado State University, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Colorado counties cooperating. Extension programs are available to all without discrimination. No endorsement of products mentioned is intended nor is criticism implied of products not mentioned.

Go to top of this page.

First Bites—Why, When, and What Solid Foods to Feed Infants

1. Sellen DW. Evolution of infant and young child feeding: implications for contemporary public health. Ann Rev Nutr. (2007) 27:123–48. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092557 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ann Rev Nutr. (2007) 27:123–48. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092557 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Herculano-Houzel S. The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its associated cost. PNAS. (2012) 109:10661–8. 10.1073/pnas.1201895109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Fonseca-Azevedo K, Herculano-Houzel S. Metabolic constraint imposes tradeoff between body size and number of brain neurons in human evolution. PNAS. (2012) 109:18571–6. 10.1073/pnas.1206390109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Organ C Nunn CL, Machanda Z, Wrangham RW. Phylogenetic rate shifts in feeding time during evolution nof Homo. PNAS. (2011) 108:14555–9. 10.1073/pnas.1107806108 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Wrangham RW, Jones JH, Laden G, Pilbeam D, Conklin-Brittain N. The raw and the stolen. Cooking and the ecology of human origins. Curr Anthropol. (1999) 40:567–94. 10.1086/300083 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1086/300083 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Herculano-Houzel S, Kaas JH. Gorilla and orangutan brain conform to the primate cellular scaling rules: implications for human evoluation. Brain Behav Evol. (2011) 77:33–44. 10.1159/000322729 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Humphrey LT. Weaning behavior in human evolution. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2010) 21:453–61. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.11.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Knott C. Reproductive ecology and human evolution. In: Ellison, editor. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; (2001). p. 429–63. [Google Scholar]

9. Sellen DW. Comparison of infant feeding patterns reported for nonindustrial populations with current recommendations. J Nutr. (2001) 131:2707–15. 10.1093/jn/131.10.2707 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. WHO . Exclusive Breast Feeding for Six Months Best for Babies Everywhere. (2011). Available online at: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/ (accessed March 24, 2020).

11. AAP Section on Breastfeeding . Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. (2012). 129:e827–e841. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. AAFP . Breastfeeding Policy Statement. (2017). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding.html (accessed March 24, 2020).

13. ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women . ACOG committee opinion no. 361: breastfeeding: maternal and infant aspects. Obstet Gynecol. (2007) 109:479–80. 10.1097/00006250-200702000-00064 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellof M, Embleton N, Fidler Mis N, et al.. Complementary feeding: a position paper by the european society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition (ESPGHAN) committee on nutrition. J Pediatr Gastro Nutr. (2017) 64:119–32. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001454 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Clayton HR, Perrine LR, Scanlon KS. Prevalence and reasons for introducing infants early to solid foods: variations by milk feeding type. Pediatrics. (2013) 131:e1108–14. 10.1542/peds.2012-2265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. (2013) 131:e1108–14. 10.1542/peds.2012-2265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Scott JA. Predictors of the early introduction of solid foods in infants: results of a cohort study. BMC Pediatr. (2009) 9:60. 10.1186/1471-2431-9-60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Costantini C, Harris H, Reddy V, Akehurst L, Fasulo A. Introducing complementary foods to infants: does age really matter? A look at feeding practices in two European Communities: British and Italian. Child Care Pract. (2019) 25:326–41. 10.1080/13575279.2017.1414033 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Orenstein SR, Magill HL, Brooks P. Thickening of infant feedings for therapy of gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. (1987) 110:181–6. 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80150-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Perkins MR, Bahnson HT, Logan K, Marrs T, Radulovic S, Craven J, et al.. Association of early introduction of solids with infant sleep: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. (2018) 172:e180739. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0739 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

JAMA Pediatr. (2018) 172:e180739. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0739 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Rosenstein D, Oster H. Differential facial responses to 4 basic tastes in newborns. Child Dev. (1988) 59:1555–68. 10.2307/1130670 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Cook CK. Taste perception in the newborn infant. Infant Behav Dev. (1978) 1:52–69. 10.1016/S0163-6383(78)80009-5 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. (1982) 3:139. 10.1016/S0195-6663(82)80007-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Schaal B, Marlier L, Soussignan R. Human fetuses learn odours from their pregnant mother's diet. Chem Senses. (2000) 25:729–37. 10.1093/chemse/25.6.729 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Hauser GJ, Chitayat D, Berns L, Braver D, Muhlbauer B. Peculiar odors in newborns and prenatal ingestion of spicy food. Eur J Pediatr. (1985) 144:403. 10. 1007/BF00441788 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1007/BF00441788 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Menella JA, Johnson A, Beauchamp GK. Garlic ingestion by pregnant women alters the odor of amniotic fluid. Chem Senses. (1995) 20:207–9. 10.1093/chemse/20.2.207 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Ross M, Nijland MJ. Fetal swallowing: relation to amniotic fluid regulation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. (1997) 40:352–65. 10.1097/00003081-199706000-00011 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Hepper PG. Human fetal olfactory learning. Int J Prenat Perinat Psychol Med. (1995) 7:145–51. [Google Scholar]

28. Menella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. (2001) 107:e88. 10.1542/peds.107.6.e88 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Hepper PG, Wells DL, Dorman JC, Lynch C. Long-term flavor recognition in humans with prenatal garlic experience. Dev Psychobiol. (2013) 55:568. 10.1002/dev.21059 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Menella JA, Beauchamp GK. Maternal diet alters the sensory qualities of human milk and the nursling's behavior. Pediatrics. (1991) 88:737–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Menella JA, Beauchamp GK. Maternal diet alters the sensory qualities of human milk and the nursling's behavior. Pediatrics. (1991) 88:737–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Maier AS, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Leathwood PD, Issanchou SN. Breastfeeding and experience with variety early in weaning increases infants' acceptance of new foods for up to two months. Clin Nutr. (2008) 27:849–57. 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.08.002 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Harris G, Mason S. Are there sensitive periods for food acceptancy in infancy? Curr Nutr Rep. (2017) 6:190–96. 10.1007/s13668-017-0203-0 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Mennella J, Beauchamp GK. Developmental changes in the acceptance of protein hydrolysate formula. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (1996) 17:386–91. 10.1097/00004703-199612000-00003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Beauchamp GK, Mennella J. Early flavor learning and its impact on later feeding behavior. J Ped Gastro Nutr. (2009) 43:S25–30. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819774a5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819774a5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Maier A, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Issanchou S, Leathwood P. Effects of repeated exposure on acceptance of initially disliked vegetables in 7-month old infants. Food Qual and Pref. (2007) 18:1023–32. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.04.005 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Remy E, Issanchou S, Chabanet C, Nicklaus S. Repeated exposure of infants at complementary feeding to a vegetable puree increases acceptance as effectively as flavor-flavor learning and more effectively than flavor-nutrient learning. J Nutr. (2013) 143:1194–200. 10.3945/jn.113.175646 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Caton SJ, Ahern SM, Remy E, Nicklaus S. Repetition counts: repeated exposure increases intake of a novel vegetable in UK pre-school children compared to flavor-flavour and flavor-nutrient learning. Br J Nutr. (2013) 109:2089–97. 10.1017/S0007114512004126 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Maier-Noth A, Schaal B, Leathwood P, Issanchou S. The lasting influences of early food-related variety experience: a longitudinal study of vegetable acceptance from 5 months to 6 years in two populations. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0151356. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

The lasting influences of early food-related variety experience: a longitudinal study of vegetable acceptance from 5 months to 6 years in two populations. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0151356. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Geisel EG. Effect of food texture on the development of chewing of children between six months and two years of age. Dev Med Child Neurol. (1991) 3:69–79. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1991.tb14786.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Blossfeld I, Collins A, Kiely M, Delahunty C. Texture preferences of 12-month-old infants and role of early experiences. Food Qual Pref. (2007) 18:396–404. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2006.03.022 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Northstone K, Emmett P, Nethersole F. The effect of age of introduction to lumpy solids on foods eaten and reported feeding difficulties at 6 and 15 months. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2001) 14:43–54. 10.1046/j.1365-277X.2001.00264.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Harris G, Coulthard H. Early eating behaviours and food acceptance revisited: breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods as predictive of food acceptance. Curr Obes Rep. (2016) 5:113–20. 10.1007/s13679-016-0202-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Harris G, Coulthard H. Early eating behaviours and food acceptance revisited: breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods as predictive of food acceptance. Curr Obes Rep. (2016) 5:113–20. 10.1007/s13679-016-0202-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Fiocchi A, Assa'ad A, Bahna S. Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Ann Allergy Asthma Allergy Immunol. (2006) 97:10–21. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61364-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Abrams EM, Greehawt M, Fleischer DM, Chan ES. Early solid food introduction: role in food allergy prevention and implications for breastfeeding. J Pediatr. (2017) 184:13–8. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.053 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al.. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. NEJM. (2015) 372:803–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414850 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Du Toit G, Sayre PH, Graham-Roberts DM, Sever ML, Lawson K, Bahnson HT, et al.. Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. NEJM. (2016) 374:1435–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Du Toit G, Sayre PH, Graham-Roberts DM, Sever ML, Lawson K, Bahnson HT, et al.. Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. NEJM. (2016) 374:1435–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Perkins MR, Logan K, Tsent A, Raji B, Ayis S, Peacock J, et al.. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. NEJM. (2016) 374:1733–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Prescott SL, Smith P, Tang M, et al.. he importance of early complementary feeding in the development of oral tolerance: concerns and controversies. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2008). 19:375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Daniels L, Mallan KM, Fildes A, Wilson J. The timing of solid introduction in an “obesogenic” environment: a narrative review of the evidence and methodologic issues. Austr and NZ J Pub Health. (2015) 39:366–73. 10.1111/1753-6405.12376 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Mehta KC, Specker BL, Bartholomy S, Giddens J, Ho ML. Trial on timing of introduction of solids and food type on infant growth. Pediatr. (1998) 102:569–73. 10.1542/peds.102.3.569 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Trial on timing of introduction of solids and food type on infant growth. Pediatr. (1998) 102:569–73. 10.1542/peds.102.3.569 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Jonsdottir OH, Kleinman RE, Wells JC, Fewtrell MS, Hibbard PL, Gunnlaugsson G, et al.. Exclusive breastfeeding for 4 versus 6 months and growth in early childhood. Acta Paediatr. (2014) 103:105–11. 10.1111/apa.12433 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Leunissen RW, Kerkhof GF, Stijnen T. Timing and tempo of first-year rapid growth in relation to cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in early adulthood. JAMA. (2009) 301:2234–42. 10.1001/jama.2009.761 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Laursen MF, Bahl MI, Michaelsen KF, Licht TR. First foods and gut microbes. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:356. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Teaching a child to solid food

The introduction of adult food is carried out gradually. It is necessary to accustom the child first to one product, then to others. Also, do not immediately take solid food - puree will be enough. If you are not in a hurry, if you are attentive enough to your child, there will be no problems. In this article, we will not talk about the introduction of complementary foods as such, but about the beginning of the use of solid foods. Chewing, swallowing are completely new skills for yesterday's baby. Someone masters them once or twice, other children need more time.

Also, do not immediately take solid food - puree will be enough. If you are not in a hurry, if you are attentive enough to your child, there will be no problems. In this article, we will not talk about the introduction of complementary foods as such, but about the beginning of the use of solid foods. Chewing, swallowing are completely new skills for yesterday's baby. Someone masters them once or twice, other children need more time.

Highlights

The structure of the maxillofacial system of the child is the main problem of all causes with chewing. The baby needs to make unusual efforts for him, carefully chew food.

The correct procedure for parents when introducing complementary foods:

• 4 months - liquid puree is introduced;

• 6 months - you can start to use puree with fibers or thick;

• 9 months - soft foods with chunks are fine.

After a year, you can give solid food - an apple, a pear, a cucumber, a piece of boiled chicken, etc. If 6-8 teeth grow earlier, these dates can be shifted. Some parents are guided by complementary feeding calendars, others are waiting for the child to ask for a certain product (usually from the parent's table).

Some parents are guided by complementary feeding calendars, others are waiting for the child to ask for a certain product (usually from the parent's table).

Different types of purees

There are qualitatively different types of products among the presented range of canned food. Manufacturers take into account the child's ability to digest a particular product and the adaptation of the gastrointestinal tract for a particular type of food. The liquid puree is similar in consistency to pancake dough. If you dip a spoon into it, and then take it out, the puree will slowly drain. There is a thick puree - it retains its shape in a spoon, since there is not much liquid in the product. We are talking about the consistency of thick sour cream, but without dietary fiber. Fibrous purees have a similar consistency to thick purees, plus they often contain lumps and fibers.

Very thick puree may be diluted. For these purposes, breast milk, vegetable broth, or a mixture are usually used.

Solid food

When the child is familiar with different types of purees, it will be possible to introduce solid food. They do this strictly according to the schedule - ordinary liquid purees are introduced after six months for naturalists, sometimes a little earlier for artificialists. Solid food will come in handy closer to a year old and later. Watch the baby's reaction - not only in terms of well-being, lack of allergies, but also in relation to personal tastes and preferences. Some children refuse certain foods completely - no need to force them.

To grind or not - see for yourself, but whole pieces are usually not given to children under one year old. There are babies who are ready to chew a piece of chicken breast for a long time, but there are not so many of them. If the food is smeared, use a nibbler - it will not have a banana on all the walls and furniture. Shredded food includes a product grated on a medium grater, but not turned into a thick or liquid puree. These include an apple from a blender, meat from a meat grinder, etc.

These include an apple from a blender, meat from a meat grinder, etc.

Soft foods like boiled vermicelli, boiled eggs, steamed rice porridge require chewing, but without much effort. Many parents begin after a year to give their child food from an adult table, this is a good option, the main thing is to cook diet meals. But the transition from formula and breast milk to adult food should be smooth.

Chewing difficulties: how not to choke

There is no universal recipe - you need to chew carefully, calmly, swallow one piece at a time. But this is all in theory - in practice, the parent sees how the child chewed and chewed a piece of food, began to swallow, and he got stuck. Insert your index finger into the mouth and, like a hook, take out food. You need to put your finger in from the side, from the corner of the mouth.

At 2 years of age, the child should be able to chew, swallow and use a spoon normally. Therefore, let your son or daughter eat on their own, despite the potential dirt that they will inevitably breed. Give up the idea of spoon-feeding a child before school and forcing them to eat food, rhymes and other traditional pastimes of our grandmothers.

Give up the idea of spoon-feeding a child before school and forcing them to eat food, rhymes and other traditional pastimes of our grandmothers.

Dad blog. We teach the child to solid food.

How to teach a child to chew food properly

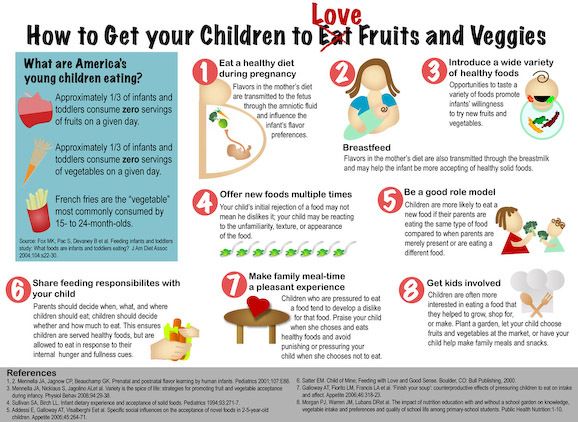

Modern man has a big problem - we do not know how to eat. Adults do not have enough time for a normal meal at a calm pace, and in most cases children are not even taught to chew. Many parents specifically feed their babies soft or pureed foods. Everyone is afraid that the child will be capricious or choke. Let's figure it out - what is the mistake of this approach and why is chewing so important?

Usually people literally swallow their food and quickly wash it down with a hot or sweet liquid, and this is where the meal ends. Among the consequences: digestive problems and regular overeating, since the body requires much more energy to absorb poorly chewed food.

The process of digestion of food begins in the oral cavity. Saliva is secreted in the mouth, which contains enzymes and breaks down easily soluble substances and softens more dense ones. Teeth and tongue grind and grind food. By the time the food enters the stomach, it will be much easier to digest and assimilate it than if you just swallow the product (otherwise it will ferment, which will negatively affect the digestive tract).

Saliva is secreted in the mouth, which contains enzymes and breaks down easily soluble substances and softens more dense ones. Teeth and tongue grind and grind food. By the time the food enters the stomach, it will be much easier to digest and assimilate it than if you just swallow the product (otherwise it will ferment, which will negatively affect the digestive tract).

According to Chinese and American studies published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, participants in the experiment consumed 11.9% fewer calories, regardless of their build, their body was satiated faster, there was less hunger and even managed to lose some weight.

We are not united with food

Chewing not only ensures a normal digestive process, but also has a number of other benefits. If in time (from 6-7 months) you start to teach the baby to chew, he will form an overbite. What's more, a Belgian study published in the journal J Voice showed that chewing promotes the proper development of speech. When a baby chews, bites, or licks, the lips, tongue, cheeks, and jaws work. This is how the same motor skills develop as when speaking. In practice, it turns out that the process of eating food is the most pleasant type of articulatory gymnastics.

When a baby chews, bites, or licks, the lips, tongue, cheeks, and jaws work. This is how the same motor skills develop as when speaking. In practice, it turns out that the process of eating food is the most pleasant type of articulatory gymnastics.

Pediatrician of the highest category Yulia Viktorovna Andronnikova told us about other functions of chewing:

- Slow chewing allows you to get enough of less food, as the signal will have time to reach the centers of regulation of hunger and appetite.

- Chewing movements activate areas of the cerebral cortex that are responsible for cognitive abilities. In children, chewing stimulates development. If this process is disturbed, dementia can progress in old age.

- Chewing movements form the facial skeleton, which is very important for proper breathing and blood supply to the central nervous system.

- Not a single cosmetic procedure will help to keep in good shape and improve the blood supply to the mimic muscles of the face like proper (slow) chewing.

How to chew

Eat consciously, disconnecting from external stimuli. Place a small portion in your mouth and chew at least 32 times. (1 for each healthy tooth + 3 for each missing one).

There is a method of therapeutic chewing:

- the first week - each spoonful of food is chewed ONE minute

- second week - TWO minutes

- third week - THREE

- fourth - TWO

- fifth - ONE

When and how to teach your child

To prepare your child for chewing, you can make faces, make faces and make chewing movements. When the baby "speaks baby", answer him. The child will repeat after you and actively move his jaws, tongue and lips.

The sooner parents introduce the child to foods of different hardness, the more willingly he will try new foods. As soon as the child began to make chewing movements, slurp and smack, he developed a food interest, and especially when the first teeth appear, you can give pieces of food (soft boiled vegetables, such as carrots). The optimal age for the first acquaintance with food is 6-7 months. Children are old enough to accept new food, but still too young to start acting up and resenting at the table.

The optimal age for the first acquaintance with food is 6-7 months. Children are old enough to accept new food, but still too young to start acting up and resenting at the table.

What to feed

Offer your child food that won't crumble in the mouth or get stuck. No bread or berries! You can give your child a banana, boiled potatoes, baby cottage cheese or a baked apple. When the child "masters" these products, offer him boiled beets, peeled cucumber or a piece of cheese.

Pitfalls

Up to six months, children have an active expulsion reflex - a natural defense against suffocation. Therefore, at the beginning of "communication" with semi-solid food, the child may choke and spit out food. There is no need to be frightened and abruptly return to mashed potatoes and ground products! Chewing is a skill and needs to be developed.

If you have introduced semi-solid food long enough and the child is still choking, give him time. Put food in front of the baby and watch - let him try to put food in his mouth with his hand on his own.