Who guidelines for baby food

When, What, and How to Introduce Solid Foods | Nutrition

For more information about how to know if your baby is ready to starting eating foods, what first foods to offer, and what to expect, watch these videos from 1,000 Days.

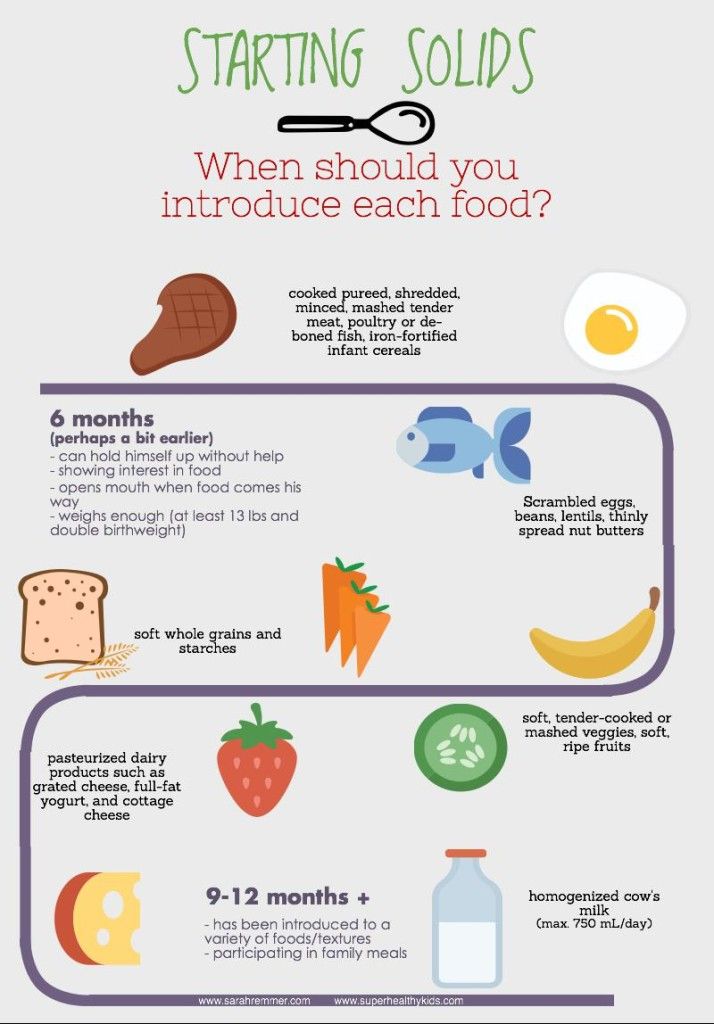

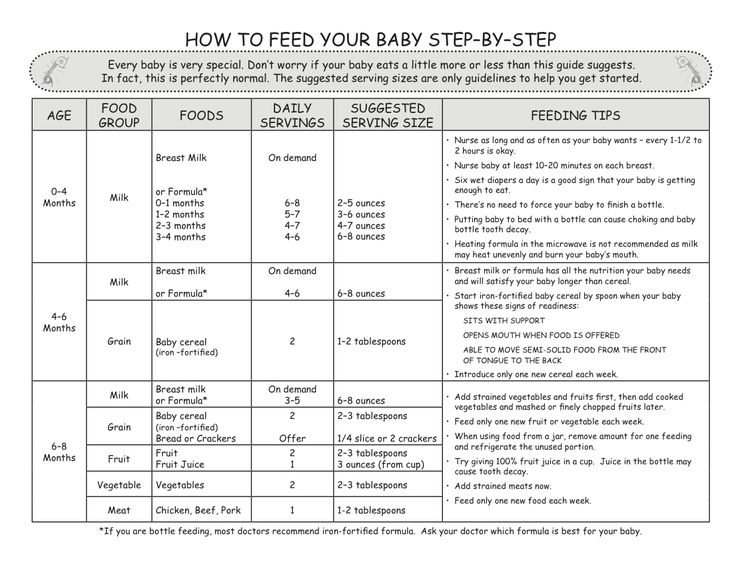

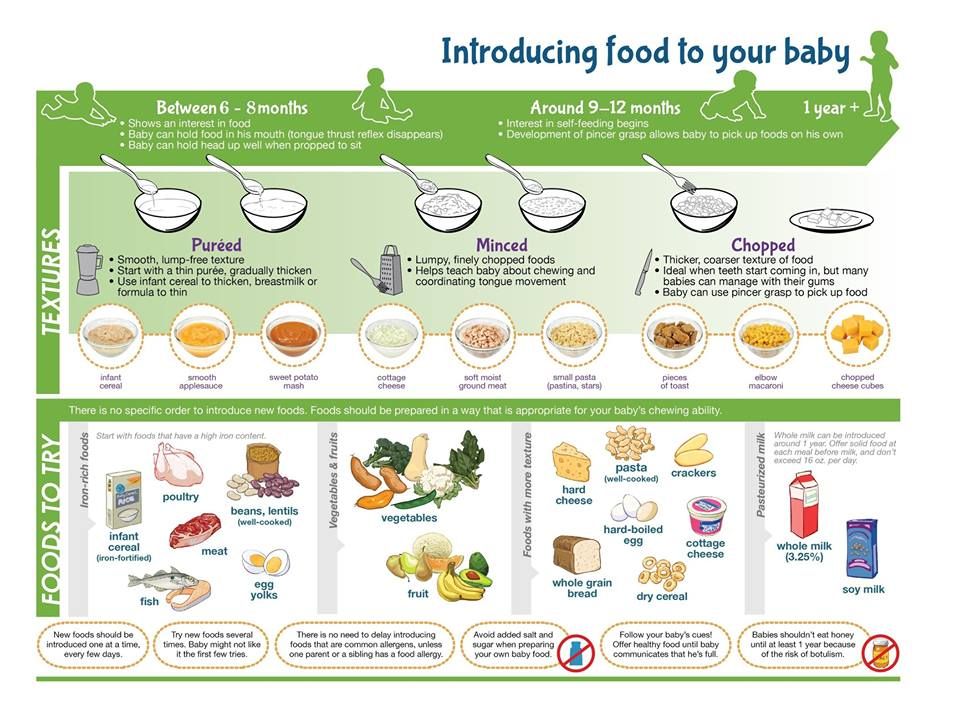

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend children be introduced to foods other than breast milk or infant formula when they are about 6 months old. Introducing foods before 4 months old is not recommended. Every child is different. How do you know if your child is ready for foods other than breast milk or infant formula? You can look for these signs that your child is developmentally ready.

Your child:

- Sits up alone or with support.

- Is able to control head and neck.

- Opens the mouth when food is offered.

- Swallows food rather than pushes it back out onto the chin.

- Brings objects to the mouth.

- Tries to grasp small objects, such as toys or food.

- Transfers food from the front to the back of the tongue to swallow.

What Foods Should I Introduce to My Child First?

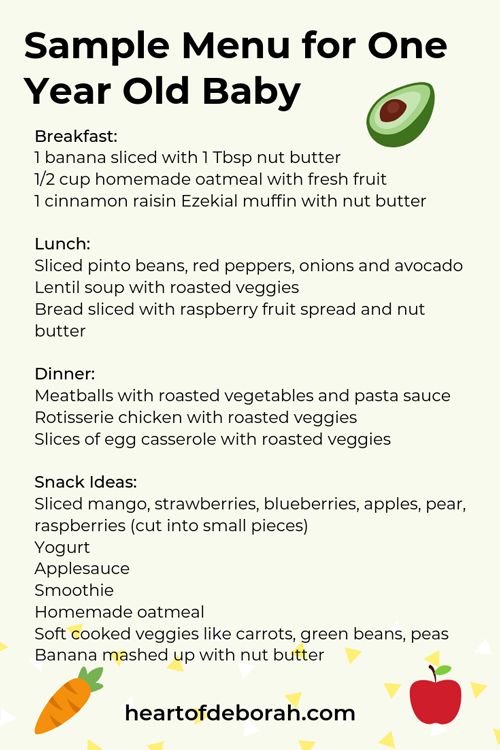

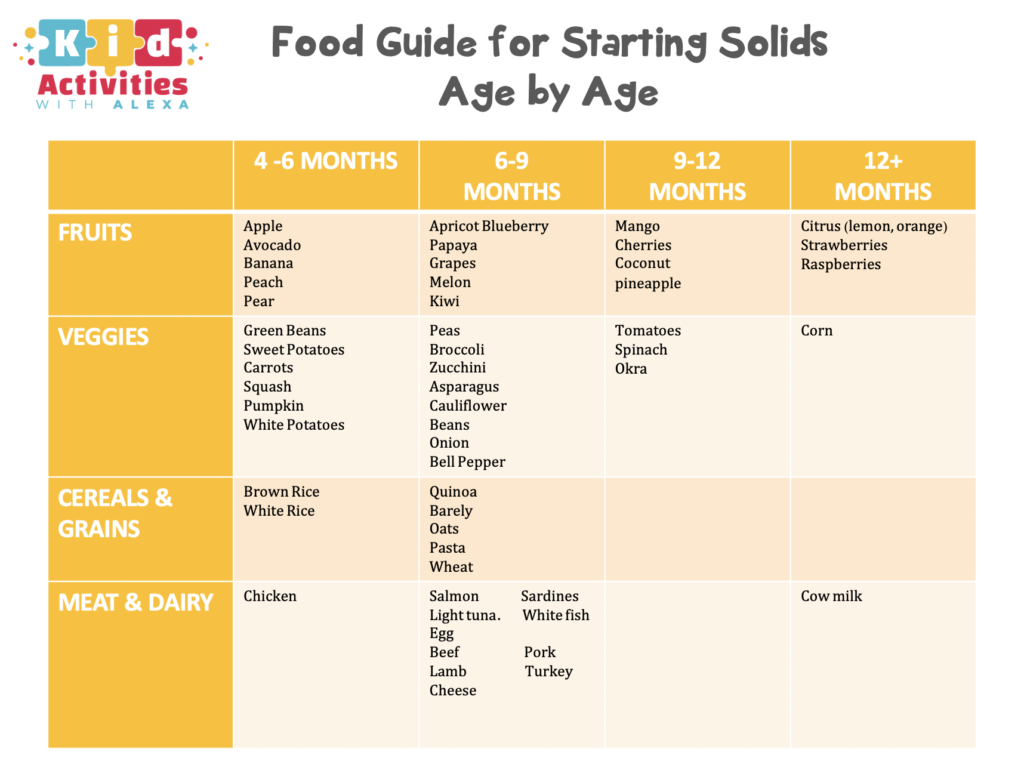

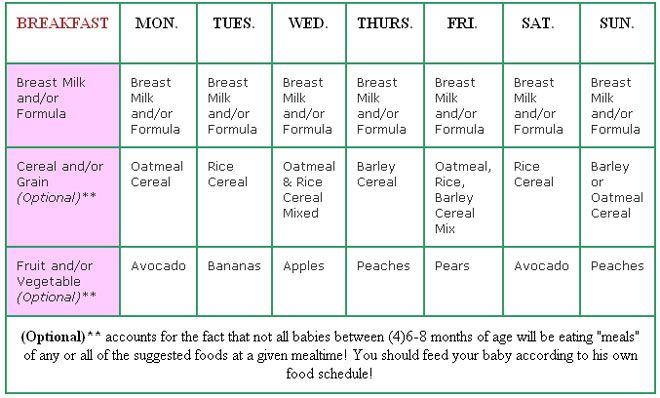

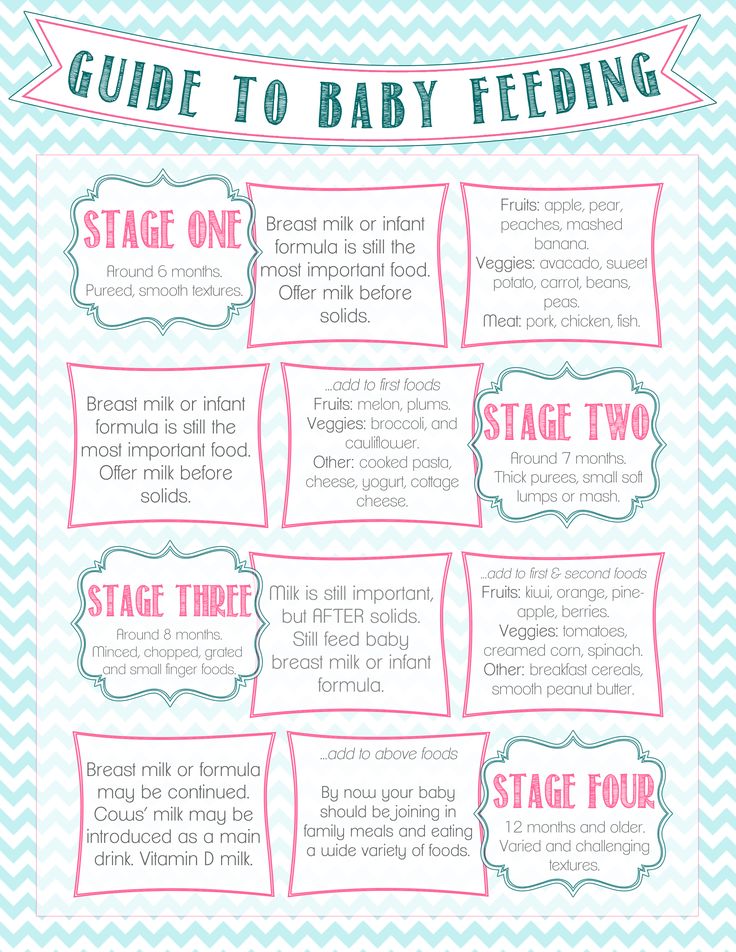

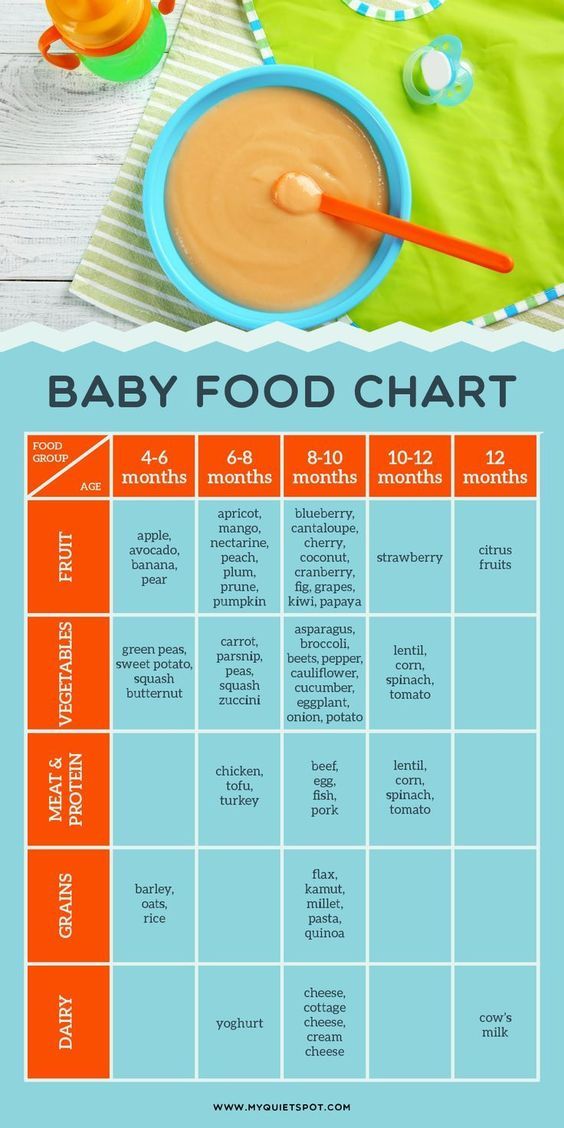

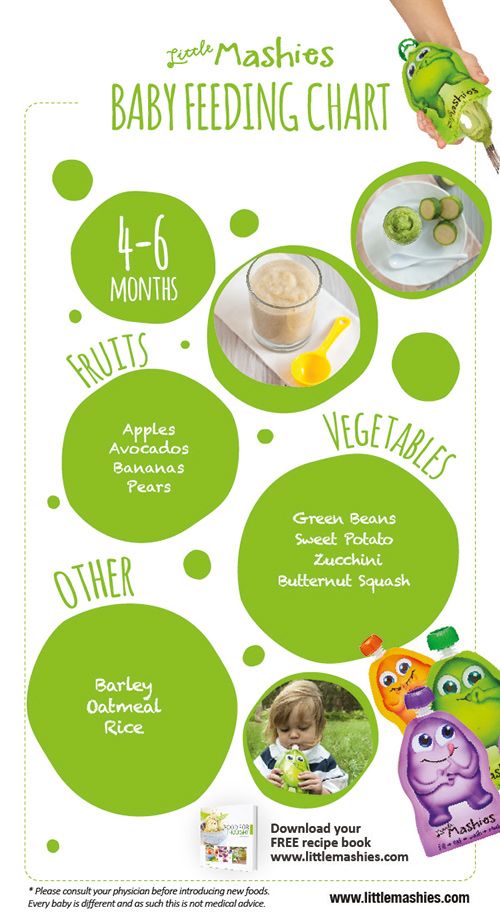

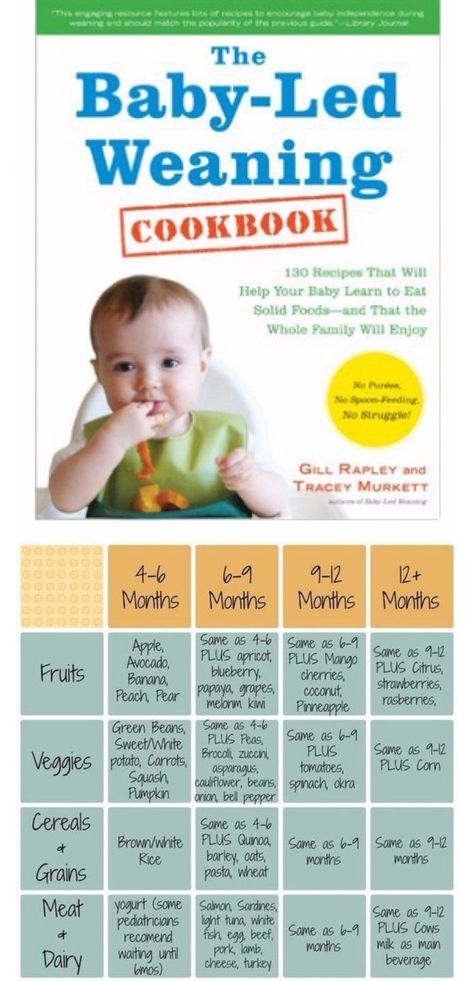

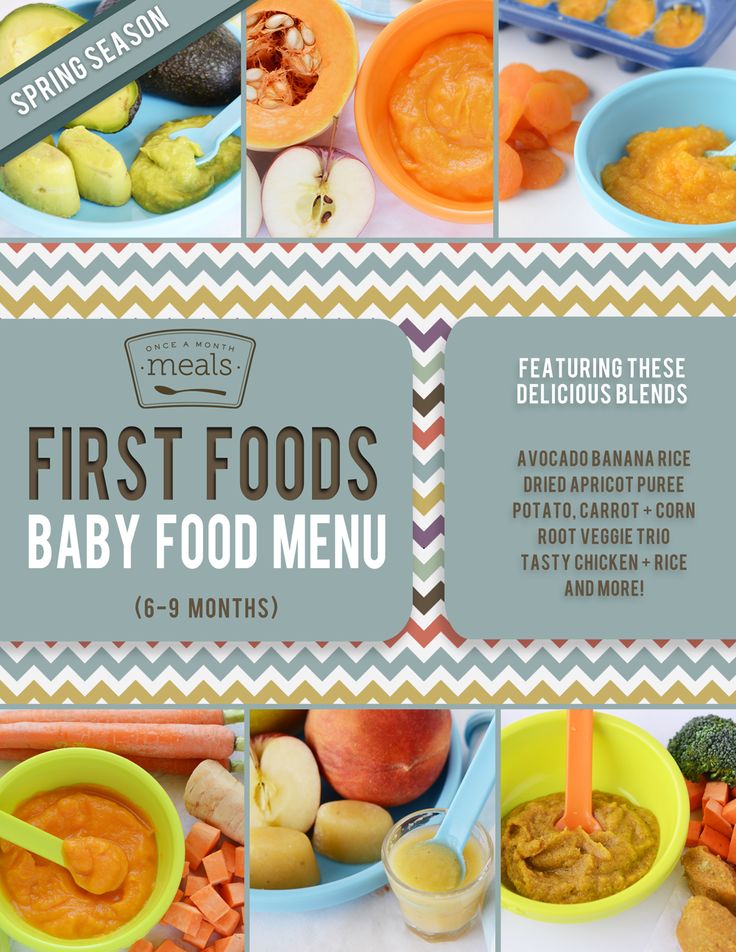

The American Academy of Pediatrics says that for most children, you do not need to give foods in a certain order. Your child can begin eating solid foods at about 6 months old. By the time he or she is 7 or 8 months old, your child can eat a variety of foods from different food groups. These foods include infant cereals, meat or other proteins, fruits, vegetables, grains, yogurts and cheeses, and more.

If your child is eating infant cereals, it is important to offer a variety of fortifiedalert icon infant cereals such as oat, barley, and multi-grain instead of only rice cereal. Only providing infant rice cereal is not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration because there is a risk for children to be exposed to arsenic. Visit the U.S. Food & Drug Administrationexternal icon to learn more.

How Should I Introduce My Child to Foods?

Your child needs certain vitamins and minerals to grow healthy and strong.

Now that your child is starting to eat food, be sure to choose foods that give your child all the vitamins and minerals they need.

Click here to learn more about some of these vitamins & minerals.

Let your child try one single-ingredient food at a time at first. This helps you see if your child has any problems with that food, such as food allergies. Wait 3 to 5 days between each new food. Before you know it, your child will be on his or her way to eating and enjoying lots of new foods.

Introduce potentially allergenic foods when other foods are introduced.

Potentially allergenic foods include cow’s milk products, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soy, and sesame. Drinking cow’s milk or fortified soy beverages is not recommended until your child is older than 12 months, but other cow’s milk products, such as yogurt, can be introduced before 12 months. If your child has severe eczema and/or egg allergy, talk with your child’s doctor or nurse about when and how to safely introduce foods with peanuts.

How Should I Prepare Food for My Child to Eat?

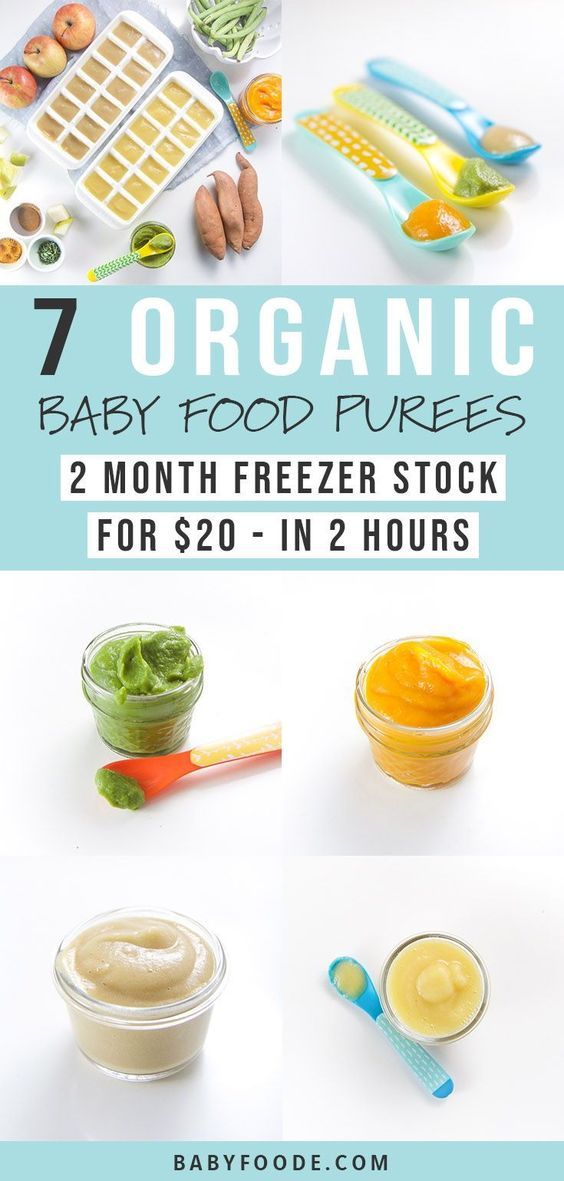

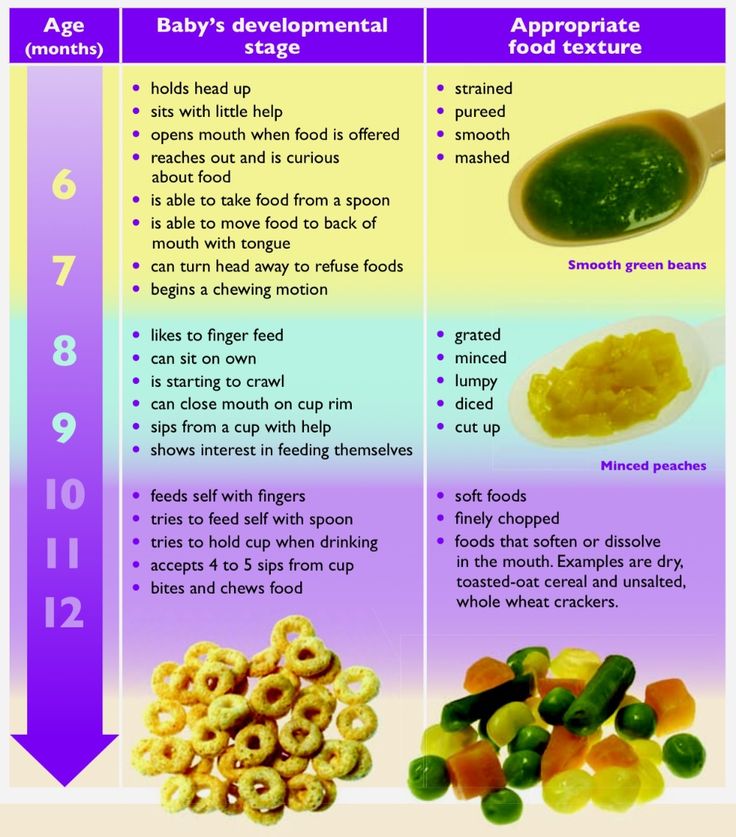

At first, it’s easier for your child to eat foods that are mashed, pureed, or strained and very smooth in texture. It can take time for your child to adjust to new food textures. Your child might cough, gag, or spit up. As your baby’s oral skills develop, thicker and lumpier foods can be introduced.

Some foods are potential choking hazards, so it is important to feed your child foods that are the right texture for his or her development. To help prevent choking, prepare foods that can be easily dissolved with saliva and do not require chewing. Feed small portions and encourage your baby to eat slowly. Always watch your child while he or she is eating.

Here are some tips for preparing foods:

- Mix cereals and mashed cooked grains with breast milk, formula, or water to make it smooth and easy for your baby to swallow.

- Mash or puree vegetables, fruits and other foods until they are smooth.

- Hard fruits and vegetables, like apples and carrots, usually need to be cooked so they can be easily mashed or pureed.

- Cook food until it is soft enough to easily mash with a fork.

- Remove all fat, skin, and bones from poultry, meat, and fish, before cooking.

- Remove seeds and hard pits from fruit, and then cut the fruit into small pieces.

- Cut soft food into small pieces or thin slices.

- Cut cylindrical foods like hot dogs, sausage and string cheese into short thin strips instead of round pieces that could get stuck in the airway.

- Cut small spherical foods like grapes, cherries, berries and tomatoes into small pieces.

- Cook and finely grind or mash whole-grain kernels of wheat, barley, rice, and other grains.

Learn more about potential choking hazards and how to prevent your child from choking.

Top of Page

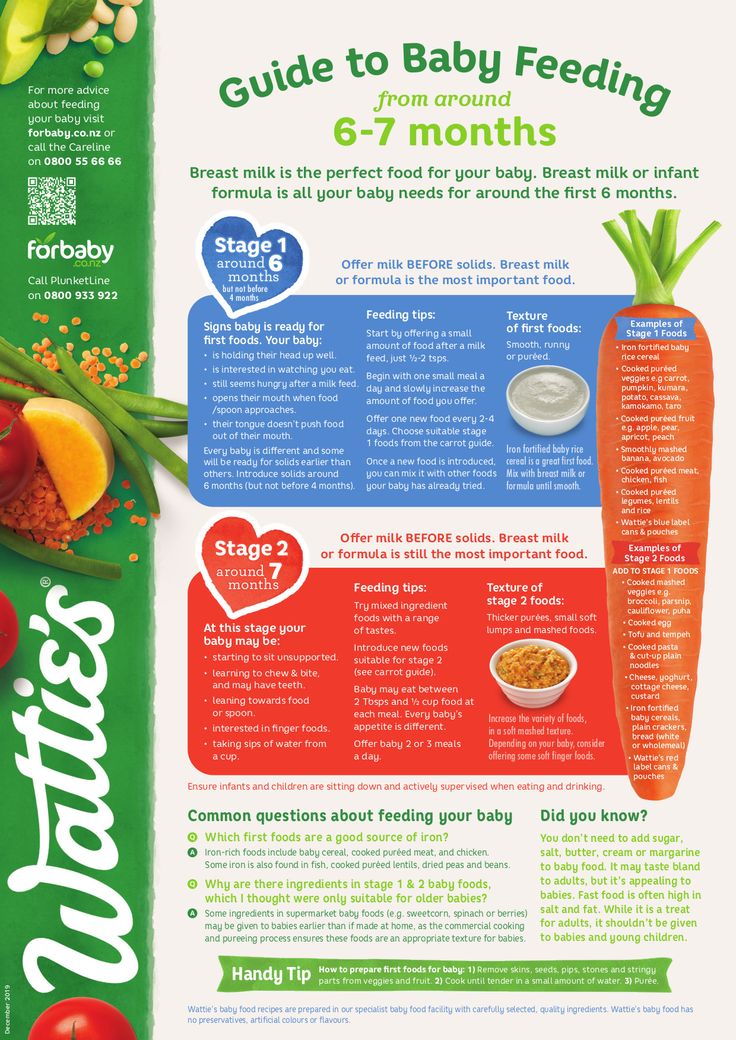

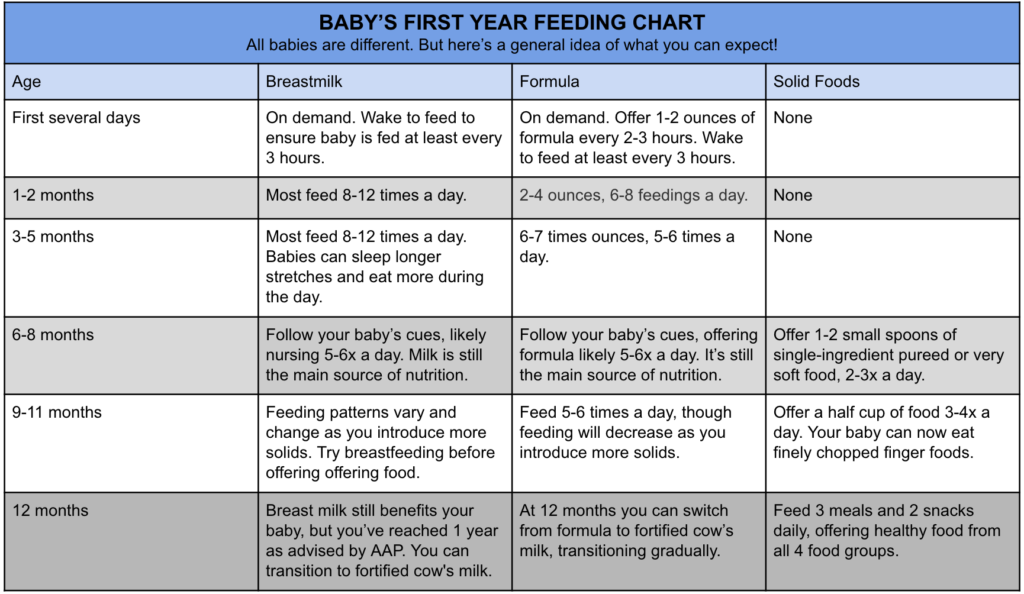

Feeding your baby: 6–12 months

At 6 months of age, breastmilk continues to be a vital source of nutrition; but it’s not enough by itself. You need to now introduce your baby to solid food, in addition to breastmilk, to keep up with her growing needs.

You need to now introduce your baby to solid food, in addition to breastmilk, to keep up with her growing needs.

Be sure you give your baby her first foods after she has breastfed, or between nursing sessions, so that your baby continues to breastfeed as much as possible.

When you start to feed your baby solid food, take extra care that she doesn’t become sick. As she crawls about and explores, germs can spread from her hands to her mouth. Protect your baby from getting sick by washing your and her hands with soap before preparing food and before every feeding.

Your baby's first foods

When your baby is 6 months old, she is just learning to chew. Her first foods need to be soft so they’re very easy to swallow, such as porridge or well mashed fruits and vegetables. Did you know that when porridge is too watery, it doesn't have as many nutrients? To make it more nutritious, cook it until it’s thick enough not to run off the spoon.

Feed your baby when you see her give signs that she's hungry – such as putting her hands to her mouth. After washing hands, start by giving your baby just two to three spoonfuls of soft food, twice a day. At this age, her stomach is small so she can only eat small amounts at each meal.

After washing hands, start by giving your baby just two to three spoonfuls of soft food, twice a day. At this age, her stomach is small so she can only eat small amounts at each meal.

The taste of a new food may surprise your baby. Give her time to get used to these new foods and flavours. Be patient and don’t force your baby to eat. Watch for signs that she is full and stop feeding her then.

As your baby grows, her stomach also grows and she can eat more food with each meal.

Feeding your baby: 6–8 months old

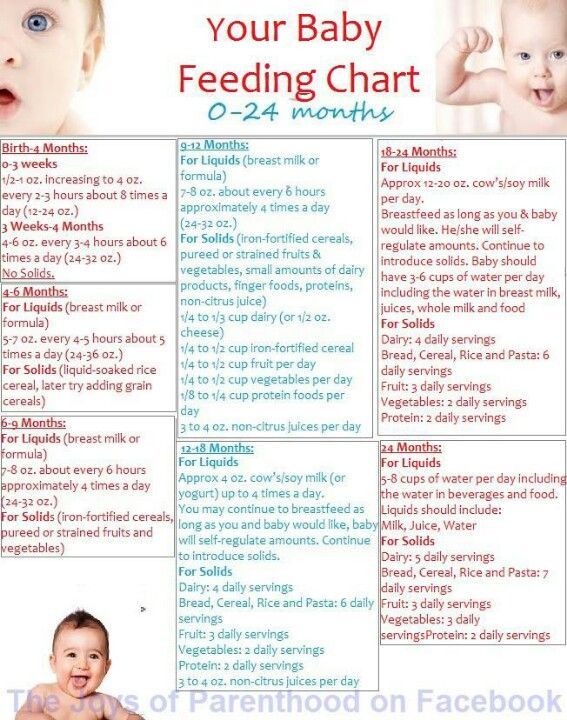

From 6–8 months old, feed your baby half a cup of soft food two to three times a day. Your baby can eat anything except honey, which she shouldn't eat until she is a year old. You can start to add a healthy snack, like mashed fruit, between meals. As your baby gets increasing amounts of solid foods, she should continue to get the same amount of breastmilk.

Feeding your baby: 9–11 months old

From 9–11 months old, your baby can take half a cup of food three to four times a day, plus a healthy snack. Now you can start to chop up soft food into small pieces instead of mashing it. Your baby may even start to eat food herself with her fingers. Continue to breastfeed whenever your baby is hungry.

Now you can start to chop up soft food into small pieces instead of mashing it. Your baby may even start to eat food herself with her fingers. Continue to breastfeed whenever your baby is hungry.

Each meal needs to be both easy for your baby to eat and packed with nutrition. Make every bite count.

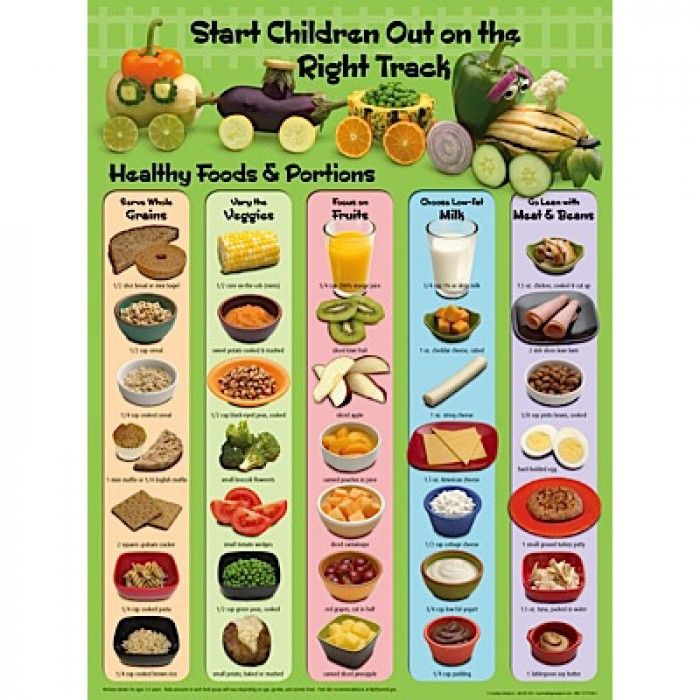

Foods need to be rich in energy and nutrients. In addition to grains and potatoes, be sure your baby has vegetables and fruits, legumes and seeds, a little energy-rich oil or fat, and – especially – animal foods (dairy, eggs, meat, fish and poultry) every day. Eating a variety of foods every day gives your baby the best chance of getting all the nutrients he needs.

If your baby refuses a new food or spits it out, don’t force it. Try again a few days later. You can also try mixing it with another food that your baby likes or squeezing a little breastmilk on top.

Feeding non-breastfed babies

If you're not breastfeeding your baby, she’ll need to eat more often. She'll also need to rely on other foods, including milk products, to get all the nutrition her body needs.

She'll also need to rely on other foods, including milk products, to get all the nutrition her body needs.

- Start to give your baby solid foods at 6 months of age, just as a breastfed baby would need. Begin with two to three spoonfuls of soft and mashed food four times a day, which will give her the nutrients she needs without breastmilk.

- From 6–8 months old, she’ll need half a cup of soft food four times a day, plus a healthy snack.

- From 9–11 months old, she’ll need half a cup of food four to five times a day, plus two healthy snacks.

Nutrition for a child up to a year and older according to WHO and UNICEF (recommendations, norms and age) - Family Clinic

Children from birth to 6 months do not need complementary foods . The ideal food created by nature for babies is mother's breast milk , with which he receives the necessary nutrients, vitamins, minerals and antibodies. If the mother does not have or does not have enough milk, then the child needs to introduce complementary foods in the form of artificial mixtures . But now this is no longer a problem, since the manufacturers of most artificial mixtures have brought the product to the proper level, which is able to fully replace breast milk. And regardless of what type of feeding the child chooses - breastfeeding or artificial formulas, the main complementary foods of the child should begin no earlier than 6 months according to the recommendations of WHO (World Health Organization) and UNICEF (UN Children's Fund), unless otherwise provided by medical recommendations as of child health. Early complementary foods (earlier than 6 months) are introduced on the recommendation of a pediatrician in accordance with medical indications, which is why it is also called pediatric .

But now this is no longer a problem, since the manufacturers of most artificial mixtures have brought the product to the proper level, which is able to fully replace breast milk. And regardless of what type of feeding the child chooses - breastfeeding or artificial formulas, the main complementary foods of the child should begin no earlier than 6 months according to the recommendations of WHO (World Health Organization) and UNICEF (UN Children's Fund), unless otherwise provided by medical recommendations as of child health. Early complementary foods (earlier than 6 months) are introduced on the recommendation of a pediatrician in accordance with medical indications, which is why it is also called pediatric .

Starting from the age of 6 months, the need of the child's body for nutrients is no longer satisfied only by mother's milk and it is necessary to gradually introduce complementary foods . At this age, babies begin to show interest in adult food. Complementary foods should be introduced with small amounts of foods new to the baby and gradually increased as the baby gets older. nine0027

Complementary foods should be introduced with small amounts of foods new to the baby and gradually increased as the baby gets older. nine0027

The child is introduced to new foods gradually, starting with very small portions. The new type of baby food includes nutritional supplements and complementary foods.

Food additives:

- fruit and berry juices;

- fruit purees;

- hen or quail egg yolk;

- cottage cheese

Complementary foods:

Complementary foods are a qualitatively new type of nutrition that meets the needs of a growing child's body in all food ingredients and accustoms to solid food. nine0004 This includes:

- vegetable purees;

- cereals;

- dairy products (kefir, yoghurt, biolact...)

Rules for the introduction of complementary foods:

- Complementary foods should be given before breastfeeding.

- Each type of complementary food should be introduced gradually, starting with a small amount (10-15 g) and increasing it to the desired volume within 7-10 days, completely replacing one breastfeed. nine0035

- You cannot enter two or more new dishes at the same time. You can switch to a new type of food only when the child gets used to the previous one.

- Complementary foods should be homogeneous in consistency and should not cause difficulty in swallowing.

- Complementary foods should only be given from a spoon.

- The number of feedings with the introduction of complementary foods is reduced to 5 times, then to 3 main and 2 snacks at the request of the child.

- The temperature of the dish should be equal to the temperature of the received mother's milk (approximately 37 C). nine0035

Supplementation scheme

Fruit and berry juice (introduced from 7-8 months)

Juice should start with drops. Within 7-10 days, bring to the required daily volume. Give after feeding or between feedings. It is advisable to use freshly made juices (must be diluted with water in a ratio of 1: 1), but juices in packages specifically designed for baby food are also suitable. The sequence of introduction of juices from berries, fruits and vegetables: apple, plum, apricot, peach, cherry, blackcurrant, pomegranate, cranberry, lemon, carrot, beet, cabbage. Citrus, tomato, raspberry, strawberry juices, juices from tropical fruits (mango, papaya, guava ...) - these juices should be given no earlier than 11-12 months. Grape juice is not recommended to include in the diet of a child at such an early age, as it can cause bloating. nine0003 Fruit and berry puree (introduced from 7 months)

Give after feeding or between feedings. It is advisable to use freshly made juices (must be diluted with water in a ratio of 1: 1), but juices in packages specifically designed for baby food are also suitable. The sequence of introduction of juices from berries, fruits and vegetables: apple, plum, apricot, peach, cherry, blackcurrant, pomegranate, cranberry, lemon, carrot, beet, cabbage. Citrus, tomato, raspberry, strawberry juices, juices from tropical fruits (mango, papaya, guava ...) - these juices should be given no earlier than 11-12 months. Grape juice is not recommended to include in the diet of a child at such an early age, as it can cause bloating. nine0003 Fruit and berry puree (introduced from 7 months)

Puree should start with 0.5 teaspoon. Within 7-10 days, bring to the required daily volume. Give after feeding or between feedings. Both freshly prepared purees and fruit and berry preserves for baby food are used.

Yolk (introduced at 8-9 months)

You need to start with 1/4 of the yolk. You can give daily until the end of the year, 1/2 yolk at the beginning of feeding, after rubbing it with milk or with a complementary food dish. nine0003 Curd (introduced at 9-10 months)

You can give daily until the end of the year, 1/2 yolk at the beginning of feeding, after rubbing it with milk or with a complementary food dish. nine0003 Curd (introduced at 9-10 months)

Start with 5 grams (1 teaspoon). Gradually, within a month, bring up to 20 grams. By the end of the first year - 50-70 g. You need to give cottage cheese at the end of feeding.

Note:

- In order to maintain lactation after weaning, it is advisable to breastfeed the baby.

- Subject to good health, optimal indicators of physical and neuropsychic development, stable and sufficient lactation in the mother, her quality nutrition, the first complementary foods can be introduced no earlier than 6 months. nine0035

- When preparing complementary foods (dairy-free cereals, mashed potatoes), the optimal liquid for diluting them is breast milk or an adapted milk formula.

Five key food safety tips:

- Food should be clean.

- Keep raw and cooked food separate.

- Food must be prepared carefully.

- Keep food at a safe temperature. nine0035

- Clean water and food must be used for food preparation.

WHO dietary guidelines for children under one year of age.

THIS IS ME FOR MYSELF!

Child nutrition guidelines for the WHO European Region with a focus on the republics of the former Soviet Union.

Introduction of complementary foods

The timely introduction of the right complementary foods contributes to the health, nutritional status and physical development of infants and young children during a period of rapid growth and should therefore be the focus of public health attention. nine0027

Throughout the period of complementary feeding, mother's milk should remain the main type of milk consumed by the infant.

Complementary foods should be introduced at about 6 months of age. Some breastfed babies may need complementary foods earlier, but not before 4 months of age.

Unmodified cow's milk should not be given before 9 months of age as a drink, but it can be used in small quantities in the preparation of complementary foods from 6-9 months of age.months. From 9-12 months, you can gradually introduce cow's milk into the baby's diet as a drink.

Complementary foods with low energy density can limit energy intake, so the average energy density should generally be at least 4.2 kJ (1 kcal)/g. This energy density depends on the frequency of meals and may be lower if meals are taken more frequently. Low-fat milk should not be given until about two years of age.

Complementary feeding should be a process of introducing baby foods that are increasingly varied in texture, taste, aroma and appearance while continuing to breastfeed. nine0027

Highly salty foods should not be given during the weaning period, and salt should not be added during this period.

What is complementary feeding?

Complementary feeding is the feeding of foods and liquids to infants in addition to breast milk. Complementary foods can be divided into the following categories:

Complementary foods can be divided into the following categories:

transitional foods are infant foods for complementary foods specially designed to meet the specific nutritional or physiological needs of an infant; nine0003 family food or homemade food is complementary baby food given to a young child that is broadly the same as the food consumed by the rest of the family.

During the transition from exclusive breastfeeding to cessation of breastfeeding, infants gradually learn to eat homemade food until it completely replaces breast milk. Children are physically able to consume foods from the family table by the age of 1, after which these foods no longer need to be modified to meet the special needs of the infant. nine0027

The age at which transitional foods are introduced is a particularly vulnerable period in a child's development. The diet is undergoing its most fundamental change - from a single product (breast milk), where the main source of energy is fat, to an ever-increasing variety of products that are required to meet nutritional needs. This transition is associated not only with increasing and changing nutritional requirements, but also with the rapid growth, physiological maturation and development of the child. nine0027

This transition is associated not only with increasing and changing nutritional requirements, but also with the rapid growth, physiological maturation and development of the child. nine0027

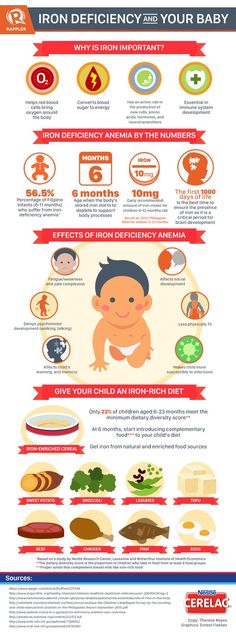

Poor nutrition and poor feeding habits and practices during this critical period can increase the risk of malnutrition (wasting and stunting) and nutritional deficiencies, especially iron, and can have long-term adverse effects on health and mental development. Therefore, among the most cost-effective interventions that health professionals can implement and support are nutritional interventions and improved feeding practices targeted at infants. nine0027

Physiological development and maturation

The ability to consume "solid" food requires the maturation of the neuromuscular, digestive, renal and defense systems.

Neuromuscular coordination

The timing of the introduction of "solid" foods and the ability of infants to consume them is affected by the maturation of neuromuscular coordination. Many food reflexes, which appear at different stages of development, either facilitate or hinder the introduction of different types of food. For example, at birth, breastfeeding is facilitated by both the latch-on reflex and the sucking-and-swallowing mechanism (1, 2), but the gag reflex may interfere with the introduction of solid foods. nine0027

Many food reflexes, which appear at different stages of development, either facilitate or hinder the introduction of different types of food. For example, at birth, breastfeeding is facilitated by both the latch-on reflex and the sucking-and-swallowing mechanism (1, 2), but the gag reflex may interfere with the introduction of solid foods. nine0027

Before 4 months of age, infants do not yet have the neuromuscular coordination to form a food bolus, transport it to the oropharynx and swallow it. Head control and spinal support are not yet developed, and therefore it is difficult for infants to maintain a position for successful absorption and swallowing of semi-solid food.

At around 5 months of age, babies begin to bring objects to their mouths, and the development of the "chewing reflex" at this time allows some solid foods to be consumed regardless of the appearance of teeth. By about 8 months of age, most babies can sit up without support, have their first teeth, and have enough tongue flexibility to swallow harder food boluses. Soon after, infants develop manipulative skills for self-feeding, drinking from a cup, holding it with both hands, and they can eat food from the family table. It is very important to encourage children to develop eating habits, such as chewing and bringing objects to their mouths, at appropriate stages. If these skills are not acquired in time, behavioral and feeding problems may occur later. nine0027

Soon after, infants develop manipulative skills for self-feeding, drinking from a cup, holding it with both hands, and they can eat food from the family table. It is very important to encourage children to develop eating habits, such as chewing and bringing objects to their mouths, at appropriate stages. If these skills are not acquired in time, behavioral and feeding problems may occur later. nine0027

Digestion and absorption

In infants, the secretion of gastric, intestinal and pancreatic digestive enzymes is not developed in the same way as in adults. However, the infant is able to fully and efficiently digest and absorb the nutrients found in breast milk, and breast milk contains enzymes that aid in the hydrolysis of fats, carbohydrates and proteins in the intestines. Similarly, in early infancy, bile salt secretion is only barely sufficient for micelle formation, and fat absorption efficiency is lower than in older children and adults. nine0027

This insufficiency can be partly compensated by bile salt-stimulated lipase, which is present in breast milk, but absent in commercial infant formulas. By about 4 months of age, stomach acid helps gastric pepsin to fully digest protein.

By about 4 months of age, stomach acid helps gastric pepsin to fully digest protein.

Although pancreatic amylase begins to fully contribute to starch digestion only at the end of the first year, most cooked starches are digested and absorbed almost completely (4). Even in the first month of life, the large intestine plays a vital role in the final digestion of those nutrients that are not completely absorbed in the small intestine. The microflora of the colon changes with age and depending on whether the child is breastfed or formula fed. The microflora ferments undigested carbohydrates and fermentable dietary fiber into short chain fatty acids that are absorbed in the colon, thereby maximizing energy utilization from carbohydrates. This process, known as "energy extraction from the colon", can provide up to 10% of the absorbed energy. nine0027

By the time an adapted food from the family table is introduced into the baby's diet at about 6 months of age, the digestive system is mature enough to efficiently digest the starches, proteins and fats found in non-dairy foods. However, the capacity of the stomach in infants is small (about 30 ml/kg of body weight). Thus, if food is too bulky and low in energy density, infants are sometimes unable to consume enough of it to meet their energy and nutrient requirements. Therefore, complementary foods should have a high energy and micronutrient density and should be given in small amounts and frequently. nine0027

However, the capacity of the stomach in infants is small (about 30 ml/kg of body weight). Thus, if food is too bulky and low in energy density, infants are sometimes unable to consume enough of it to meet their energy and nutrient requirements. Therefore, complementary foods should have a high energy and micronutrient density and should be given in small amounts and frequently. nine0027

Renal function

Renal solute load refers to the total amount of solutes that must be excreted by the kidneys. It mainly includes food components that are not transformed during metabolism, mainly electrolytes sodium, chlorine, potassium and phosphorus, which have been absorbed in excess of the body's needs, and end products of metabolism, the most important of which are nitrogen compounds formed as a result of digestion and protein metabolism. nine0027

Potential solute burden on the kidney refers to solutes of dietary and endogenous origin that would need to be excreted in the urine if not used in new tissue synthesis or excreted by non-renal pathways. It is defined as the sum of four electrolytes (sodium, chloride, potassium, and phosphorus) plus solutes derived from protein metabolism, which typically account for over 50% of the potential solute load on the kidneys. nine0027

It is defined as the sum of four electrolytes (sodium, chloride, potassium, and phosphorus) plus solutes derived from protein metabolism, which typically account for over 50% of the potential solute load on the kidneys. nine0027

The newborn baby has too limited kidney capacity to handle the high solute load and retain fluids at the same time. The osmolarity of mother's milk corresponds to the capabilities of the child's body, so the concern about the excessive load of dissolved substances on the kidneys primarily concerns children who are not breastfeeding, especially children who are fed unmodified cow's milk. This anxiety is especially justified during the period of illness. By about 4 months, kidney function is much more mature and infants are better able to conserve water and deal with higher solute concentrations. Thus, recommendations for the introduction of complementary foods usually do not need to be changed to match the developmental stage of the renal system. nine0027

Defense system

A vital defense mechanism is the development and maintenance of an effective mucosal barrier in the gut. In the newborn, the mucosal barrier is immature, as a result of which it is not protected from damage by enteropathogenic microorganisms and is sensitive to the action of some antigens contained in food. Breast milk contains a wide range of factors not found in commercial infant formulas that stimulate the development of active defense mechanisms and help prepare the gastrointestinal tract for the absorption of transitional foods. Non-immunological defense mechanisms that help protect the intestinal surface from microorganisms, toxins, and antigens include gastric acidity, mucosa, intestinal secretions, and peristalsis. nine0027

In the newborn, the mucosal barrier is immature, as a result of which it is not protected from damage by enteropathogenic microorganisms and is sensitive to the action of some antigens contained in food. Breast milk contains a wide range of factors not found in commercial infant formulas that stimulate the development of active defense mechanisms and help prepare the gastrointestinal tract for the absorption of transitional foods. Non-immunological defense mechanisms that help protect the intestinal surface from microorganisms, toxins, and antigens include gastric acidity, mucosa, intestinal secretions, and peristalsis. nine0027

The relatively weak defense mechanisms of the infant's digestive tract at an early age, as well as reduced gastric acidity, increase the risk of mucosal damage by foreign food and microbiological proteins, which can cause direct toxic or immunologically mediated damage. Some foods contain proteins that are potential antigens, such as soy protein, gluten (found in some grain products), proteins in cow's milk, eggs, and fish, which have been associated with enteropathy. Therefore, it seems reasonable to avoid introducing these foods before 6 months of age, especially when there is a family history of food allergy. nine0027

Therefore, it seems reasonable to avoid introducing these foods before 6 months of age, especially when there is a family history of food allergy. nine0027

Why do we need complementary foods?

As the child grows and becomes more active, breast milk alone is not enough to fully meet his nutritional and physiological needs. To compensate for the difference between the amount of energy, iron and other essential nutrients provided by exclusive breastfeeding and the total nutritional needs of the infant, an adapted family food (transition food) is needed. With age, this difference increases and requires an increasing contribution of food other than breast milk to the supply of energy and nutrients, especially iron. Complementary foods also play an important role in the development of neuromuscular coordination. nine0027

Infants do not have the physiological maturity to move from exclusive breastfeeding directly to food from the family table. Therefore, to bridge this gap between needs and opportunities, specially adapted family foods (transitional foods) are needed, and the need for them lasts up to about 1 year, until the child is mature enough to consume ordinary homemade food. When transitional foods are introduced, the baby is also exposed to a variety of textures and textures, and this contributes to the development of vital motor skills such as chewing. nine0027

When transitional foods are introduced, the baby is also exposed to a variety of textures and textures, and this contributes to the development of vital motor skills such as chewing. nine0027

When should complementary foods be introduced?

The optimal age of transition food introduction can be determined by comparing the advantages and disadvantages of different times.

The extent to which breast milk can provide sufficient energy and nutrients to support growth and prevent deficiencies, as well as the risk of morbidity, especially infectious and allergic diseases, from the consumption of contaminated food and "foreign" dietary proteins should be assessed. Other important considerations include physiological development and maturity, various developmental indicators that indicate an infant's readiness to feed, and factors related to the mother such as nutritional status, the impact of decreased suckling on the mother's fertility and her ability to care for the baby, as well as existing principles and methods of care for young children (Chapter 9).

Starting complementary foods too early has its dangers because:

breast milk can be displaced by complementary foods, and this will lead to a decrease in breast milk production, and therefore the risk of insufficient intake of energy and nutrients by the child;

infants are exposed to pathogenic microbes present in foods and fluids that can be contaminated and thereby increase the risk of dyspepsia and hence malnutrition; nine0003 the risk of dyspepsia and food allergies increases due to the immaturity of the intestines, and because of this, the risk of malnutrition increases;

, mothers return to fertility more quickly, as reduced breastfeeding reduces the period during which ovulation is suppressed.

Problems also arise when complementary foods are introduced too late because:

inadequate energy and nutrient intake from breastmilk alone can lead to stunted growth and malnutrition; nine0003 due to the inability of breast milk to meet the needs of the child, micronutrient deficiencies, especially iron and zinc, may develop;

Optimal development of motor skills, such as chewing, and the child's positive perception of the new taste and texture of food may not be ensured.

Therefore, it is necessary to introduce complementary foods at the right time, at the appropriate stages of development.

Much controversy remains over when exactly to start introducing complementary foods. And while everyone agrees that the optimal age is individual for each individual child, the question of whether to recommend the introduction of complementary foods at the age of “4 to 6 months or at about 6 months” remains open. It should be clarified that "6 months" is defined as the end of the first six months of a child's life when he is 26 weeks old, and not the beginning of the sixth month, i.e. 21-22 weeks. Similarly, "4 months" refers to the end, not the beginning, of the fourth month of life. nine0027

There is near universal agreement that complementary foods should not be started before 4 months of age and delayed beyond 6 months of age. In the resolutions of the World Health Assembly in 1990 and 1992. "4-6 months" is recommended, while the 1994 resolution recommends "about 6 months". Several more recent WHO and UNICEF publications use both formulations. A WHO review (Lutter, 6) concluded that the scientific basis for the recommendation of 4–6 months was not well documented. In a recent WHO/UNICEF report on complementary feeding in developing countries (7), the authors recommended that full-term infants be exclusively breastfed until about 6 months of age. nine0027

Several more recent WHO and UNICEF publications use both formulations. A WHO review (Lutter, 6) concluded that the scientific basis for the recommendation of 4–6 months was not well documented. In a recent WHO/UNICEF report on complementary feeding in developing countries (7), the authors recommended that full-term infants be exclusively breastfed until about 6 months of age. nine0027

Many recommendations in industrialized countries use a period of 4-6 months. However, recent official guidelines published in the Netherlands (8) state that breastfed children who are of adequate growth should not, from a nutritional point of view, receive any complementary foods until about 6 months of age. If parents decide to start complementary foods earlier, this is quite acceptable, provided that the child is at least 4 months old. In addition, in a statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics (9) an age of “about 6 months” is recommended, and this has been adopted by various Member States of the WHO European Region when they adapted and implemented Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) training programs for health professionals (see Annex 3).

When deciding whether to recommend 4-6 months or approximately 6 months, care must be taken to assess how this is interpreted by parents or health professionals. Health care providers may misinterpret the advice and encourage the introduction of complementary foods by 4 months, just "just in case". As a result, parents may think that their children should be eating complementary foods by 4 months of age and therefore begin to introduce “new flavors” of food before 4 months of age (7). Therefore, national authorities should evaluate how their recommendations are interpreted by parents and health professionals. nine0027

In countries in transition, there is evidence of an increased risk of infectious diseases when complementary foods are introduced before 6 months of age, and that introducing complementary foods before this age does not improve the rate of weight gain and length gain (10, 11). Moreover, exclusive breastfeeding for the first approximately 6 months offers health benefits. In adverse environmental conditions, even if there is a slight increase in energy intake with the introduction of complementary foods, the energy expenditure in response to increased morbidity associated with the introduction of foods and liquids other than breast milk (which is especially likely in unhygienic environments) eventually leads to there is no net benefit in terms of energy balance. In terms of nutrients, the potential benefits of introducing complementary foods are likely to be offset by losses from increased morbidity and reduced bioavailability of breast milk nutrients when complementary foods are given along with breast milk. In settings where nutritional deficiencies in infants under 6 months of age are a concern, improving maternal nutrition may be a more effective and less risky way to prevent maternal and infant nutritional deficiencies. Optimal maternal nutrition during pregnancy and breastfeeding not only guarantees high quality milk for the baby, but also maximizes the mother's ability to care for her baby.

In adverse environmental conditions, even if there is a slight increase in energy intake with the introduction of complementary foods, the energy expenditure in response to increased morbidity associated with the introduction of foods and liquids other than breast milk (which is especially likely in unhygienic environments) eventually leads to there is no net benefit in terms of energy balance. In terms of nutrients, the potential benefits of introducing complementary foods are likely to be offset by losses from increased morbidity and reduced bioavailability of breast milk nutrients when complementary foods are given along with breast milk. In settings where nutritional deficiencies in infants under 6 months of age are a concern, improving maternal nutrition may be a more effective and less risky way to prevent maternal and infant nutritional deficiencies. Optimal maternal nutrition during pregnancy and breastfeeding not only guarantees high quality milk for the baby, but also maximizes the mother's ability to care for her baby. nine0027

nine0027

For the WHO European Region, the recommendation is that infants should be exclusively breastfed from birth to about 6 months and for at least the first 4 months of life. Some babies may need complementary foods before 6 months of age, but should not be introduced before 4 months of age. The need for complementary foods before 6 months of age is indicated by the fact that the child, in the absence of obvious illness, is not gaining enough weight (as determined by two or three consecutive assessments) (see Chapter 10) or appears hungry after unrestricted breastfeeding. Care should be taken to use the correct growth target charts, bearing in mind that breastfed children do not grow at the same rate as those on which the US National Center for Health Statistics guidelines are based (12). However, when introducing complementary foods before 6 months of age, other factors need to be considered, such as body weight and fetal age at birth, the clinical condition and overall growth and nutritional status of the child. A study in Honduras (13) found that feeding breastfed infants with a birth weight of 1500 to 2500 g with free high-quality complementary foods from 4 months of age did not provide any physical benefits. development. These results support the recommendation to exclusively breastfeed for about 6 months, even for small babies. nine0027

A study in Honduras (13) found that feeding breastfed infants with a birth weight of 1500 to 2500 g with free high-quality complementary foods from 4 months of age did not provide any physical benefits. development. These results support the recommendation to exclusively breastfeed for about 6 months, even for small babies. nine0027

Composition of complementary foods

In Chapter 3, estimates were given of the average energy required from complementary foods at different ages. The effect of different levels of breast milk intake and different energy densities of complementary foods on the frequency of meals required to meet energy requirements was examined, taking into account the limitations in food volume dictated by the capacity of the stomach. In the next section, these issues are raised again and discussed in more detail. The physical properties of starch are analyzed in terms of the density of the main food given as complementary foods. On this basis, possible changes in the preparation of the main meal are proposed, which should help to obtain such food that is neither too thick for consumption by an infant, nor so thin that it has a reduced energy and nutrient density. The following are ways to improve the nutrient density of the main meal by adding other complementary foods, as well as other factors that affect the amount of food consumed (such as taste and aroma) and the amount of each nutrient actually absorbed (bioavailability and nutritional density). ). nine0027

The following are ways to improve the nutrient density of the main meal by adding other complementary foods, as well as other factors that affect the amount of food consumed (such as taste and aroma) and the amount of each nutrient actually absorbed (bioavailability and nutritional density). ). nine0027

Energy density and viscosity

The main factors influencing the extent to which an infant can meet its energy and nutrient requirements are the consistency and energy density (amount of energy per unit volume) of complementary foods and frequency of feeding. The main source of energy is often starch, but when heated with water, starch grains gelatinize and form a voluminous, thick (viscous) porridge. Because of these physical properties, it is difficult for infants to swallow and digest such porridge. In addition, the low calorie and nutritional density means that the infant needs to eat large amounts of food to meet the needs of the infant. This is usually not possible due to the limited capacity of an infant's stomach and the limited number of meals per day. Diluting thick porridge to make it easier to swallow further reduces its energy density. Traditionally, complementary foods are low in energy density and low in protein, and although their liquid consistency makes them easier to consume, the volumes needed to meet a baby's energy and nutrient requirements often exceed the maximum amount an infant can swallow. Adding a small amount of vegetable oil can make food softer and easier to consume, even when cold. However, adding a large amount of sugar or lard, while increasing the energy density, will increase the viscosity (thickness) and therefore make the food too heavy to consume in large quantities. nine0027

Diluting thick porridge to make it easier to swallow further reduces its energy density. Traditionally, complementary foods are low in energy density and low in protein, and although their liquid consistency makes them easier to consume, the volumes needed to meet a baby's energy and nutrient requirements often exceed the maximum amount an infant can swallow. Adding a small amount of vegetable oil can make food softer and easier to consume, even when cold. However, adding a large amount of sugar or lard, while increasing the energy density, will increase the viscosity (thickness) and therefore make the food too heavy to consume in large quantities. nine0027

Therefore, complementary foods should be rich in energy, protein and micronutrients and have a texture that makes them easy to consume. In some countries in the developing world, this problem is solved by adding amylase-rich flour to thick porridge, which reduces the viscosity of the porridge without reducing its energy and nutrient content (14). Amylase-rich flour is obtained by sprouting cereal grains, which leads to the activation of amylase enzymes, which then break down starch into sugars (maltose, maltodextrins and glucose). nine0027

Amylase-rich flour is obtained by sprouting cereal grains, which leads to the activation of amylase enzymes, which then break down starch into sugars (maltose, maltodextrins and glucose). nine0027

When starch breaks down, it loses its ability to absorb water and swell, and therefore porridge made from sprouted grains amylase-rich flour has a high energy density, retaining a semi-liquid texture, but increased osmolarity. The preparation of such flours is time consuming and tedious, but they can be prepared in large quantities and added little by little to thin the porridge as needed (15). They can also be produced commercially at low cost. nine0027

Starchy foods can also be improved by mixing with other foods, but it is extremely important to know the effect of such additions not only on the viscosity of the food, but also on the density of the proteins and micronutrients in the food. For example, while adding animal fats, vegetable oil, or margarine increases energy density, it negatively impacts protein and micronutrient density. Therefore, starchy foods need to be fortified with foods that increase their energy, protein, and micronutrient content. This can be achieved by adding milk (breast milk, commercial infant formula, or small amounts of cow's milk or fermented milk products), which improves protein quality and increases the density of key nutrients. nine0027

Therefore, starchy foods need to be fortified with foods that increase their energy, protein, and micronutrient content. This can be achieved by adding milk (breast milk, commercial infant formula, or small amounts of cow's milk or fermented milk products), which improves protein quality and increases the density of key nutrients. nine0027

Nutritional density and bioavailability

The amount of nutrients available for an infant's physical and mental development depends both on their amount in breast milk and transitional foods and on their bioavailability. Bioavailability is defined as the absorption of nutrients and their availability for use in metabolism, while nutrient density is the amount of a nutrient per unit of energy, such as 100 kJ, or per unit weight, such as 100 g.

There are large differences in nutrient density and micronutrient bioavailability between animal and plant foods. Animal products usually contain more of certain nutrients per unit of energy, such as vitamins A, D and E, riboflavin, vitamin B12, calcium and zinc. The iron content of some animal products (such as liver, meat, fish, and poultry) is high, while other foods (milk and dairy products) are low. In contrast, the density of thiamine, vitamin B6, folic acid, and vitamin C is generally higher in plant foods, and some, such as legumes and corn, also contain significant amounts of iron. In general, the bioavailability of minerals found in plant foods is poorer compared to minerals found in animal foods. nine0027

The iron content of some animal products (such as liver, meat, fish, and poultry) is high, while other foods (milk and dairy products) are low. In contrast, the density of thiamine, vitamin B6, folic acid, and vitamin C is generally higher in plant foods, and some, such as legumes and corn, also contain significant amounts of iron. In general, the bioavailability of minerals found in plant foods is poorer compared to minerals found in animal foods. nine0027

Micronutrients with low bioavailability in plant foods include iron, zinc, calcium and beta-carotene in leafy and some other vegetables. In addition, the absorption of beta-carotene, vitamin A, and other fat-soluble vitamins is hindered when the diet is low in fat.

Diets with high bioavailability of nutrients are varied and high in legumes and foods rich in vitamin C, with small amounts of meat, fish and poultry. Diets with low nutrient bioavailability consist mainly of grains, legumes, and root vegetables, with negligible amounts of meat, fish, or foods rich in vitamin C.

Variety, flavor and aroma

To meet the energy and nutritional needs of growing children, they need to be offered a wide range of foods with high nutritional value. In addition, it is possible that when children are offered a more varied diet, this improves their appetite. Although the pattern of food intake changes with each meal, children regulate their energy intake at subsequent meals so that the total daily energy intake usually remains relatively constant. However, the amount of energy consumption on different days can also vary slightly. Although children have their own preferences, when given different foods, children usually choose a set that includes their favorite foods, and end up with a nutritionally complete diet. nine0027

A child's intake of transitional foods can be influenced by a range of organoleptic properties such as taste, aroma, appearance and texture. The taste buds of the tongue perceive four primary taste qualities: sweet, bitter, salty and sour. Sensitivity to taste helps protect against eating harmful substances and can also help regulate how much a child eats.

Sensitivity to taste helps protect against eating harmful substances and can also help regulate how much a child eats.

Although children do not need to learn to like sweet or savory foods, there is strong evidence that children's preferences for most other foods are greatly influenced by learning and experience (16). The only innate preference in humans is a preference for sweet tastes, and even newborn babies are voracious eaters of sweet substances. This can be a problem as children develop a preference for the frequency of exposure to a given taste. Avoiding all foods other than sweets will limit the variety of foods and nutrients your child can eat. nine0027

Compared to a monotonous diet, children eat more when they receive a variety of foods. It is important that children who are initially unfamiliar with all foods have repeated access to new foods during the complementary feeding period so that they develop a healthy positive food perception system. It has been suggested that food should be tasted at least 8–10 times, and a clear increase in positive food perception occurs after 12–15 times (17). Thus, parents need to be reassured and told that refusal to eat is normal. Foods must be offered many times, as those foods that the child initially refuses are often accepted later. If the child's initial refusal is interpreted as permanent, the product will likely no longer be offered to the child and the opportunity to have access to new foods and taste experiences will be lost. nine0027

Thus, parents need to be reassured and told that refusal to eat is normal. Foods must be offered many times, as those foods that the child initially refuses are often accepted later. If the child's initial refusal is interpreted as permanent, the product will likely no longer be offered to the child and the opportunity to have access to new foods and taste experiences will be lost. nine0027

The process of introducing complementary foods depends on whether the child has learned to enjoy the new food. Breastfed babies may respond faster to solid foods than babies fed commercial infant formula because they are accustomed to the different flavors and odors transmitted through breast milk (18)

What are the best foods to prepare for breastfeeding? children?

The choice of products used for complementary foods varies significantly among different categories of the population due to different traditions and varying degrees of availability. The next section discusses the use of various complementary foods. A new WHO report (19) provides a convenient way to calculate the contribution of various foods to fill the energy and nutrient gaps that occur when breast milk no longer meets the growing needs of the infant.

A new WHO report (19) provides a convenient way to calculate the contribution of various foods to fill the energy and nutrient gaps that occur when breast milk no longer meets the growing needs of the infant.

Plant products

In addition to nutrients, foods contain combinations of other substances, most of which are found in abundance in plants. No single product can provide the body with all the nutrients (with the exception of breast milk for infants in the first months of life). For example, potatoes provide vitamin C but no iron, while bread and dry beans provide iron but no vitamin C. Therefore, a healthy diet should contain a variety of foods to prevent disease and promote growth. nine0027

Plant foods contain biologically active compounds, or metabolites, that have been used in traditional herbal and herbal medicines for centuries. The isolation, detection and quantification of these plant metabolites is associated with their potentially protective role, and interest in their detection has arisen due to epidemiological data, according to which some of them protect against the development of cancer and cardiovascular diseases in adults.

It is also possible that such components have a beneficial effect on young children, although scientific evidence for this is not enough. Many metabolites found in plants are not food substances in the traditional sense and are sometimes referred to as "non-nutrient substances". This includes substances such as dietary fiber and related substances, phytosterols, lignans, flavonoids, glucosinolates, phenols, terpenes, and compounds from plants in the onion family. nine0027

In order to ensure the intake of all these protective substances, it is important to eat as varied plant foods as possible. There is no need to take vitamin supplements or herbal extracts as a substitute or supplement for a healthy diet, and for medical reasons this is not usually recommended.

Cereal products

Cereal products are the main food of almost all categories of the population. Foods such as wheat, buckwheat, barley, rye, oats and rice make a significant contribution to the diet in the WHO European Region.