Baby spills milk after feeding

Why is my baby spitting up so much breast milk?

Video visit appointments available 7 days a week from 9:00am to 11:00pm. Learn More >>

COVID-19 Updates: Get the latest on vaccine information, in-person appointments, video visits and more. Learn More >>

Latest Blog Posts

Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Center Receives Gift from The Faris Foundation to Bring Novel Therapies to Patients with Brain Tumors

Texas Children’s Celebrates 10th Anniversary of its Medical Legal Partnership

Third time’s a charm

It was worth every mile

Five Years of Seizure-Free Living, Thanks to Texas Children’s

Department

Texas Children's Hospital West Campus

Texas Children's Pediatrics

Texas Children's Hospital The Woodlands

- Home

- Texas Children's Blog

Image

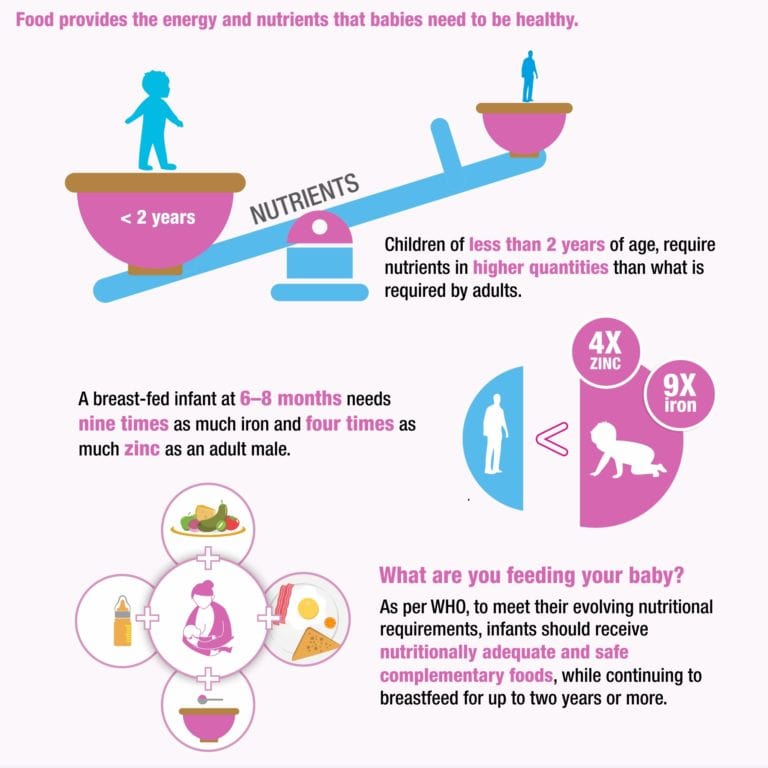

My baby is frequently spitting up – it seems like it’s all of my breast milk! I never thought breastfed babies spit up this much. This can’t be normal, can it? Is there something wrong with my baby?

Don’t worry – we get these questions often. Caring for a baby who spits up can be stressful for parents, creating worries about the baby’s health and proper growth. Spitting up is a very common occurrence in healthy babies, and usually won’t cause any issues in regards to the baby’s growth or development. This often happens because the baby’s digestive system is so immature, making it easier for their stomach contents to flow back up into the esophagus.

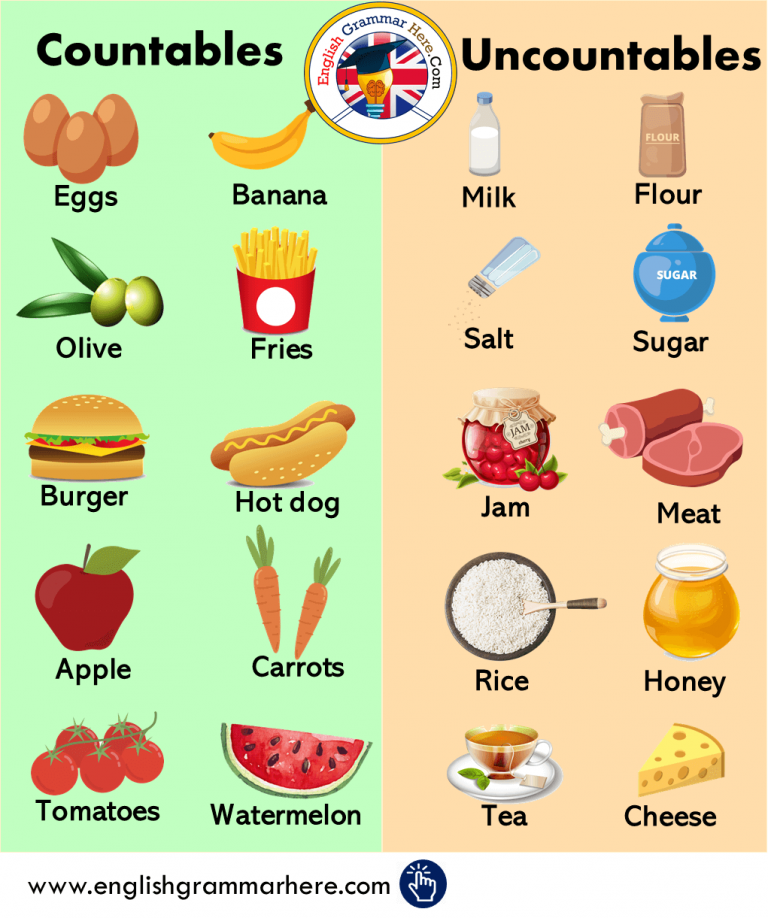

Several different factors can contribute to babies spitting up, including:

- Babies regularly spit up when they drink too much milk, too quickly. This can happen when the baby feeds very fast, or when mom’s breasts are overfull. The amount of spit up can appear to be much more than it really is.

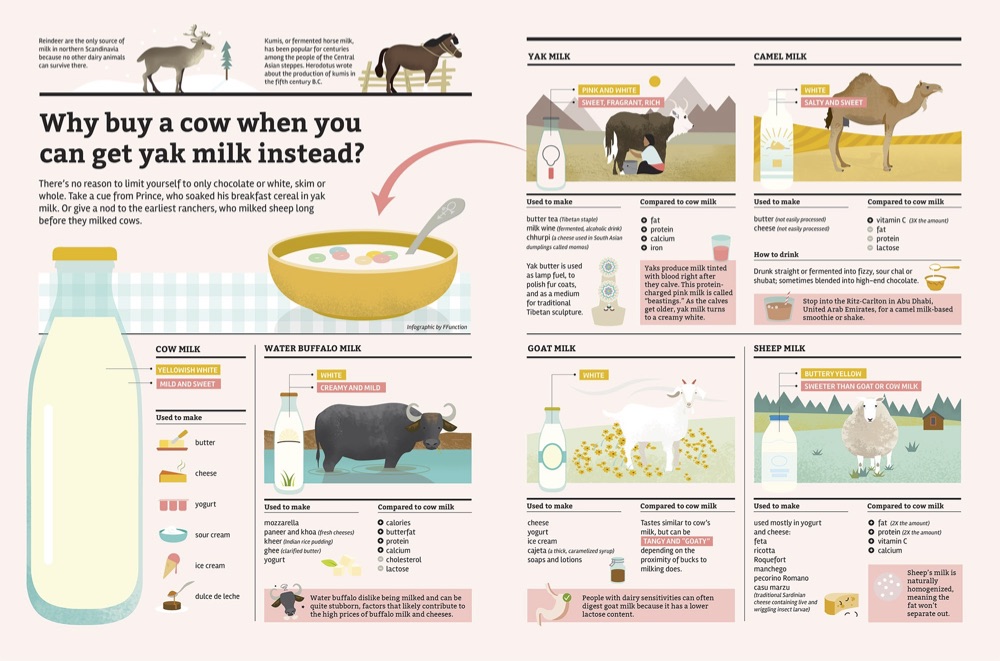

- Food sensitivities can cause excessive spitting up in babies. Products with cow milk in the mom or baby’s diet can be a common food sensitivity.

- Some babies can become distracted when feeding at the breast, pulling off to look around.

This can cause babies to swallow air and spit up more often.

This can cause babies to swallow air and spit up more often. - Breastmilk oversupply or forceful let-down (milk ejection reflex) can cause reflux-like symptoms in babies.

If your baby seems comfortable, is eating well, gaining weight and developing normally, there’s typically little cause for concern. “Happy spitters” will grow and thrive, despite spitting up frequently. As babies grow and get older, they usually spit up less. Most will stop spitting up by 12 months of age.

Consider these tips:

- Keep your baby upright. Try feeding your baby this way and keep them upright for about 30 minutes after feedings.

- Avoid engaging in immediate active play for at least 30 minutes after feedings. Active play includes use of a bouncy seat, vibrating seat, infant swing or bouncing the baby while walking/holding.

- Frequent burps during and after each feeding can keep air from building up in your baby’s stomach.

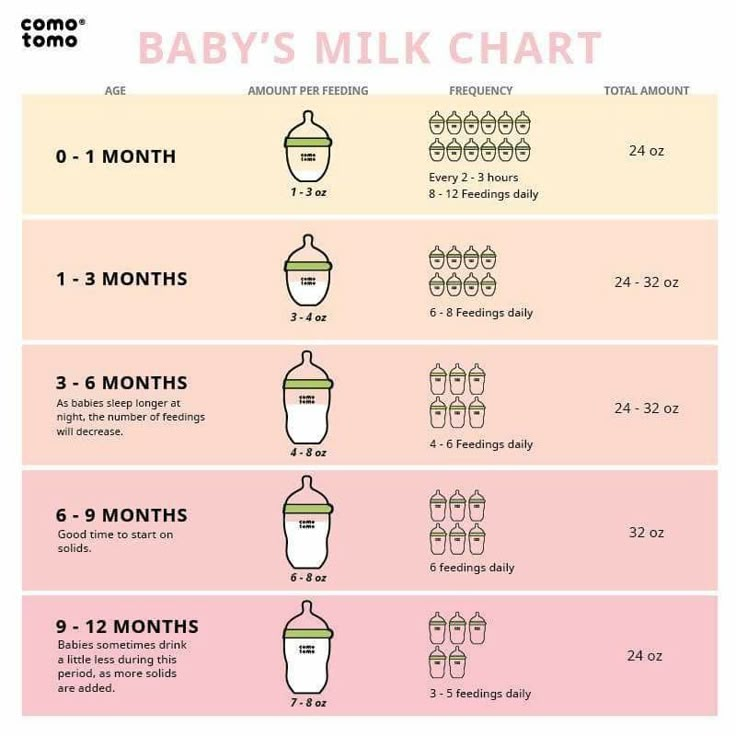

- Avoid overfeeding. Feeding your baby smaller amounts more frequently might help decrease spitting up.

- Put your baby to sleep on his or her back. Placing a baby to sleep on its tummy to prevent spitting up is not recommended.

- Monitor your diet closely if you’re breastfeeding. If you feel there are certain foods that might be upsetting your baby’s stomach, try avoiding them for a while.

- If you notice weight loss, forceful spit up, fussiness or other symptoms, talk to your child’s pediatrician about your concerns.

Lactation Support Services at Texas Children’s Hospital offers a variety of services to mothers with questions and concerns regarding breastfeeding, pumping, medications and more. Click here to learn more.

Shelly Nalbone, APRN, CPNP, IBCLC

Why Babies Spit Up - HealthyChildren.org

By: Alejandro Velez, MD, FAAP & Christine Waasdorp Hurtado, MD, FAAP

All babies spit up. Some babies spit up more than others, or at certain times.

Typically, babies spit up after they gulp down some air with breastmilk or formula. A baby's stomach is small and can't hold a lot, after all. Milk and air can fill it up quickly.

With a full stomach, any change in position such as bouncing or sitting up can force the flap between the esophagus (food pipe) and stomach to open. And when that flap (the esophageal sphincter) opens, that's when some of what your baby just ate can make a return appearance.

So, what can you do―if anything―to reduce the amount of your baby's spit up? How do you know if your baby's symptoms are part of a larger problem? Read on to learn more.

Common concerns parents have about spit up

My baby spits up a little after most feedings.

Possible cause: Gastroesophageal reflux (normal if mild)

Action to take: None. The spitting up will grow less frequent and stop as your baby's muscles mature—especially that flap we talked about earlier.

It often just takes time.

It often just takes time.

My baby gulps their feedings and seems to have a lot of gas.

Possible cause: Aerophagia (swallowing more air than usual)

Action to take: Make sure your baby is positioned properly during feeds. Also be sure to burp the baby during and after feeds. Consider trying a different bottle to decrease your baby's ability to suck in air.

My baby spits up when you bounce them or play with them after meals.

My baby's spitting up has changed to vomiting with muscle contractions that occur after every feeding. The vomit shoots out with force.

I found blood in my baby's spit-up or vomit.

Possible cause: Swelling of the esophagus or stomach (esophagitis or gastritis), or another health problem that requires diagnosis and treatment.

Action to take: Call you pediatrician right away so they can examine your baby.

Remedies for spitty babies

Regardless of whether or not your baby's spit up warrants watchful waiting or medical intervention, there are some simple feeding suggestions that can help you deal with the situation at hand.

5 tips to reduce your baby's spit up

Avoid overfeeding. Like a gas tank, fill baby's stomach it too full (or too fast) and it's going to spurt right back out at you. To help reduce the likelihood of overfeeding, feed your baby smaller amounts more frequently.

Burp your baby more frequently. Extra gas in your baby's stomach has a way of stirring up trouble. As gas bubbles escape, they have an annoying tendency to bring the rest of the stomach's contents up with them. To minimize the chances of this happening, burp not only after, but also during meals.

Limit active play after meals and hold your baby upright. Pressing on a baby's belly right after eating can up the odds that anything in their stomach will be forced into action.

While

tummy time is important for babies, postponing it for a while after meals can serve as an easy and effective avoidance technique.

While

tummy time is important for babies, postponing it for a while after meals can serve as an easy and effective avoidance technique.Consider the formula. If your baby is formula feeding, there's a possibility that their formula could be contributing to their spitting up. While some babies simply seem to fare better with one formula over another without having a true allergy or intolerance, an estimated 5% of babies are genuinely unable to handle the proteins found in milk or soy formula―a condition called Cow Milk Protein Intolerance/Allery (CMPI and CMPA). In either case, spitting up may serve as one of several cues your baby may give you that it's time to discuss alternative formulas with your pediatrician. If your baby does have a true intolerance, a 1- or 2-week trial of hypoallergenic (hydrolyzed) formula designed to be better tolerated might be recommended by your baby's provider.

If breastfeeding, consider your diet.

Cow's milk and soy in your diet can worsen spit up in infants with Cow Milk Protein Intolerance/Allergy (CMPI and CMPA). Removing these proteins can help to reduce or eliminate spit up.

Cow's milk and soy in your diet can worsen spit up in infants with Cow Milk Protein Intolerance/Allergy (CMPI and CMPA). Removing these proteins can help to reduce or eliminate spit up.Try a little oatmeal. Giving babies cereal before 6 months is generally not recommended—with one possible exception. Babies and children with dysphagia or reflux, for example, may need their food to be thicker in order to swallow safely or reduce reflux. In response to concerns over arsenic in rice, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) now recommends parents of children with these conditions use of oatmeal instead of rice cereal. See Oatmeal: The Safer Alternative for Infants & Children Who Need Thicker Food for more information.

Vomit vs. spit up: what's the difference?

There is a big difference between vomiting and spitting up:

Vomiting is the forceful throwing up of stomach contents through the mouth. This typically involves using the abdominal muscles and is often uncomfortable, leaving you with a crying child.

This typically involves using the abdominal muscles and is often uncomfortable, leaving you with a crying child.

Spitting up is the easy flow of stomach contents out of the mouth, frequently with a burp. Spitting up doesn't involve forceful muscle contractions, brings up only small amounts of milk, and doesn't distress your baby or make them uncomfortable.

What causes vomiting?

Vomiting occurs when the abdominal muscles and diaphragm contract vigorously while the stomach is relaxed. This reflex action is triggered by the "vomiting center" in the brain after it has been stimulated by:

Nerves from the stomach and intestine when the gastrointestinal tract is either irritated or swollen by an infection or blockage (as in the stomach bug)

Chemicals in the blood such as drugs

Psychological stimuli from disturbing sights or smells

Stimuli from the middle ear (as in vomiting caused by motion sickness)

Always contact your pediatrician if your baby vomits forcefully after every feeding or if there is ever blood in your baby's vomit.

Remember

The best way to reduce spit up is to feed your baby before they get very hungry. Gently burp your baby when they take breaks during feedings. Limit active play after meals and hold your baby in an upright position for at least 20 minutes. Always closely supervise your baby during this time.

More information

- How to Keep Your Sleeping Baby Safe: AAP Policy Explained

- Gastroesophageal Reflux & Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Parent FAQs

-

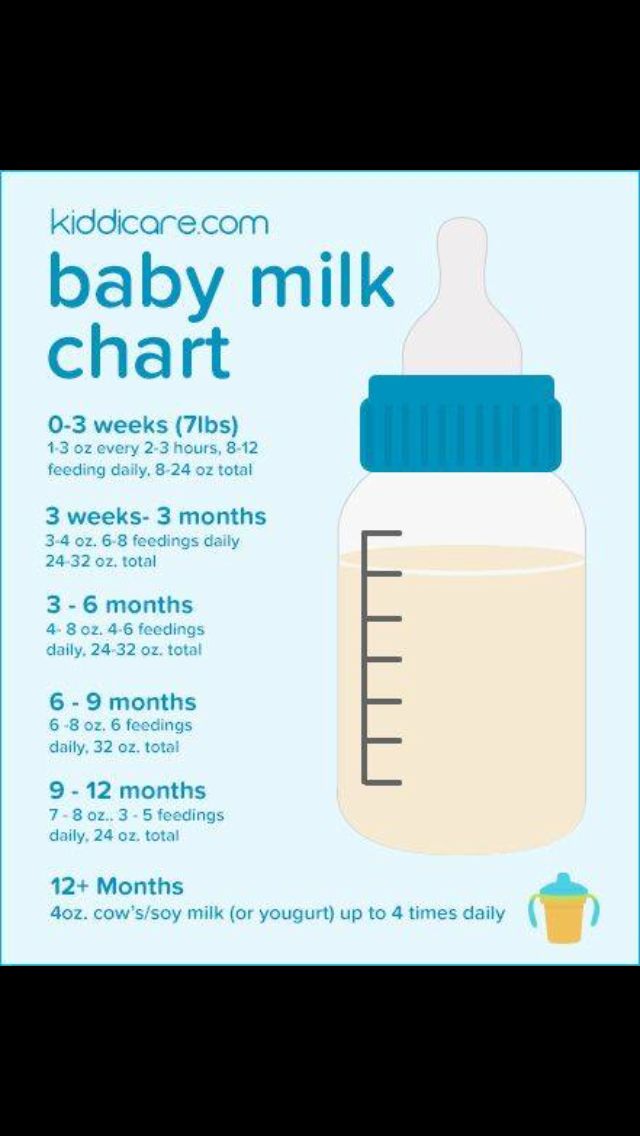

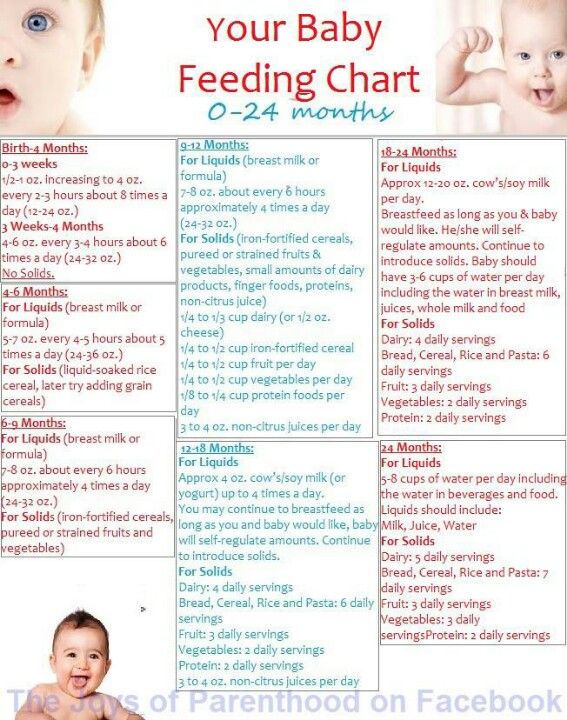

How Much and How Often Should Your Baby Eat

About Dr. Velez

Alejandro Velez, MD, FAAP is a second-year gastroenterology fellow at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital who is interested in practicing general gastroenterology with a focus in motility and functional GI disorders, has a love for medical education at all levels, and harbors a passion for supporting and uplifting those that identify as unrepresented minorities in medicine. |

About Dr. Waasdorp

Christine Waasdorp Hurtado, MD, MSCS, FAAP is a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. She is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and practices in Colorado Springs. |

- Last Updated

- 10/5/2022

- Source

- American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (Copyright © 2022)

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

Breastfeeding in the first month: what to expect

Not sure how to establish lactation and increase milk production? If you need help, support, or just want to know what to expect, read our first month breastfeeding advice

Share this information

The first weeks of breastfeeding are a very stressful period. If at times you feel like you can't handle it, know that you are not alone. Feeding your baby all day long is completely natural and helps produce breast milk, but can be quite tiring at times. Be patient, think about yourself and remember: after the first month, when milk production stabilizes, it will become easier.

How often should a baby be breastfed?

Babies are born with a small stomach that grows rapidly with increasing milk production: in the first week it is no larger than an apricot, and after two weeks it is already the size of a large chicken egg. 1.2 Let the child eat as much as he wants and when he wants. This will help him quickly regain the weight lost after birth and grow and develop further.

This will help him quickly regain the weight lost after birth and grow and develop further.

“Be prepared to feed every two to three hours throughout the day. At night, the intervals between feedings can be longer: three to four or even five hours, says Cathy Garbin, a recognized international expert on breastfeeding. Some eat quickly and are satiated in 15 minutes, while others take an entire hour to feed. Do not compare your breastfeeding regimen with that of other mothers - it is very likely that there will be nothing in common between them.

At each feed, give your baby a full meal from one breast and then offer a second one, but don't worry if the baby doesn't take it. When the baby is full, he lets go of his chest and at the same time looks relaxed and satisfied - so much so that he can immediately fall asleep. The next time you feed, start on the other breast. You can monitor the order of the mammary glands during feeding using a special application.

Why does the child always ask for a breast?

The first month is usually the hardest time to breastfeed. But do not think that since the child is constantly hungry and asks for a breast almost every 45 minutes, then you do not have enough milk.

But do not think that since the child is constantly hungry and asks for a breast almost every 45 minutes, then you do not have enough milk.

In the first month, the baby needs to eat frequently to start and stimulate the mother's milk production. It lays the foundation for a stable milk supply in the future. 3

In addition, we must not forget that the child needs almost constant contact with the mother. The bright light and noise of the surrounding world at first frighten the baby, and only by clinging to his mother, he can calm down.

Sarah, mother of three from the UK, confirms: “Crying is not always a sign of hunger. Sometimes my kids just wanted me to be around and begged for breasts to calm them down. Use a sling. Place the cradle next to the bed. Don't look at the clock. Take advantage of every opportunity to relax. Forget about cleaning. Let those around you take care of you. And not three days, but six weeks at least! Hug your baby, enjoy the comfort - and trust your body. "

"

Do I need to feed my baby on a schedule?

Your baby is still too young for a strict daily routine, so

forget about breastfeeding schedules and focus on his needs.

“Volumes have been written about how to feed a baby on a schedule, but babies don't read or understand books,” Cathy says. - All children are different. Some people can eat on a schedule, but most can't. Most often, over time, the child develops his own schedule.

Some mothers report that their babies are fine with scheduled feedings, but they are most likely just the few babies who would eat every four hours anyway. Adults rarely eat and drink the same foods at the same time of day - so why do we expect this from toddlers?

Offer your baby the breast at the first sign of hunger. Crying is already the last stage, so be attentive to early signs: the baby licks his lips, opens his mouth, sucks his fist, turns his head with his mouth open - looking for the breast. 4

What is a "milk flush"?

At the beginning of each feed, a hungry baby actively sucks on the nipple,

thereby stimulating the milk flow reflex - the movement of milk through the milk ducts. 5

5

“Nipple stimulation triggers the release of the hormone oxytocin,” explains Cathy. “Oxytocin is distributed throughout the body and causes the muscles around the milk-producing glands to contract and the milk ducts to dilate. This stimulates the flow of milk.

If the flushing reflex fails, milk will not come out. This is a hormonal response, and under stress it may not work at all or work poorly. Therefore, it is so important that you feel comfortable and calm when feeding.

“Studies show that each mother has a different rhythm of hot flashes during one feed,” Kathy continues, “Oxytocin is a short-acting hormone, it breaks down in just 30-40 seconds after formation. Milk begins to flow, the baby eats, the effect of oxytocin ends, but then a new rush of milk occurs, the baby continues to suckle the breast, and this process is repeated cyclically. That is why, during feeding, the child periodically stops and rests - this is how nature intended.

The flow of milk may be accompanied by a strong sensation of movement or tingling in the chest, although 21% of mothers, according to surveys, do not feel anything at all. 5 Cathy explains: “Many women only feel the first rush of milk. If you do not feel hot flashes, do not worry: since the child eats normally, most likely, you simply do not understand that they are.

5 Cathy explains: “Many women only feel the first rush of milk. If you do not feel hot flashes, do not worry: since the child eats normally, most likely, you simply do not understand that they are.

How do you know if a baby is getting enough milk?

Since it is impossible to track how much milk a baby eats while breastfeeding, mothers sometimes worry that the baby is malnourished. Trust your child and your body.

After a rush of milk, the baby usually begins to suckle more slowly. Some mothers clearly hear how the baby swallows, others do not notice it. But one way or another, the child himself will show when he is full - just watch carefully. Many babies make two or three approaches to the breast at one feeding. 6

“When a child has had enough, it is noticeable almost immediately: a kind of “milk intoxication” sets in. The baby is relaxed and makes it clear with his whole body that he is completely full, says Katie, “Diapers are another great way to assess whether the baby is getting enough milk. During this period, a breastfed baby should have at least five wet diapers a day and at least two portions of soft yellow stool, and often more.”

During this period, a breastfed baby should have at least five wet diapers a day and at least two portions of soft yellow stool, and often more.”

From one month until weaning at six months of age, a baby's stool (if exclusively breastfed) should look the same every day: yellow, grainy, loose, and watery.

When is the child's birth weight restored?

Most newborns lose weight in the first few days of life. This is normal and should not be cause for concern. As a rule, weight is reduced by 5-7%, although some may lose up to 10%. One way or another, by 10–14 days, almost all newborns regain their birth weight. In the first three to four months, the minimum expected weight gain is an average of 150 grams per week. But one week the child may gain weight faster, and the next slower, so it is necessary that the attending physician monitor the health and growth of the baby constantly. 7.8

At the slightest doubt or signs of dehydration, such as

dark urine, no stool for more than 24 hours, retraction of the fontanel (soft spot on the head), yellowing of the skin, drowsiness, lethargy, lack of appetite (ability to four to six hours without feeding), you should immediately consult a doctor. 7

7

What is "cluster feeding"?

When a baby asks to breastfeed very often for several hours, this is called cluster feeding. 6 The peak often occurs in the evening between 18:00 and 22:00, just when many babies are especially restless and need close contact with their mother. Most often, mothers complain about this in the period from two to nine weeks after childbirth. This is perfectly normal and common behavior as long as the baby is otherwise healthy, eating well, gaining weight normally, and appears content throughout the day. 9

Cluster feeding can be caused by a sharp jump in the development of the body - during this period the baby especially needs love, comfort and a sense of security. The growing brain of a child is so excited that it can be difficult for him to turn off, or it just scares the baby. 9 If a child is overworked, it is often difficult for him or her to calm down on his own, and adult help is needed. And breastfeeding is the best way to calm the baby, because breast milk is not only food, but also pain reliever and a source of happiness hormones. 10

And breastfeeding is the best way to calm the baby, because breast milk is not only food, but also pain reliever and a source of happiness hormones. 10

“Nobody told me about cluster feeding, so for the first 10 days I just went crazy with worry - I was sure that my milk was not enough for the baby,” recalls Camille, a mother from Australia, “It was a very difficult period . I was advised to pump and supplement until I finally contacted the Australian Breastfeeding Association. There they explained to me what was happening: it turned out that it was not about milk at all.

Remember, this is temporary. Try to prepare dinner for yourself in the afternoon, when the baby is fast asleep, so that in the evening, when he begins to often breastfeed, you have the opportunity to quickly warm up the food and have a snack. If you are not alone, arrange to carry and rock the baby in turns so that you have the opportunity to rest. If you have no one to turn to for help and you feel that your strength is leaving you, put the baby in the crib and rest for a few minutes, and then pick it up again.

Ask your partner, family and friends to help you with household chores, cooking and caring for older children if you have any. If possible, hire an au pair. Get as much rest as possible, eat well and drink plenty of water.

“My daughter slept a lot during the day, but from 23:00 to 5:00 the cluster feeding period began, which was very tiring,” recalls Jenal, a mother from the USA, “My husband tried his best to make life easier for me - washed, cleaned, cooked, changed diapers, let me sleep at every opportunity and never tired of assuring me that we were doing well.

If you are concerned about the frequency of breastfeeding, it is worth contacting a specialist. “Check with a lactation consultant or doctor to see if this is indicative of any problems,” recommends Cathy. “Resist the temptation to supplement your baby with formula (unless recommended by your doctor) until you find the cause. It may not be a matter of limited milk production at all - it may be that the child is inefficiently sucking it.

When will breastfeeding become easier?

This early stage is very special and does not last long. Although sometimes it seems that there will be no end to it, rest assured: it will get easier soon! By the end of the first month, breast milk production will stabilize, and the baby will become stronger and learn to suckle better. 2.3 Any problems with latch on by this time will most likely be resolved and the body will be able to produce milk more efficiently so inflammation and leakage of milk will begin to subside.

“The first four to six weeks are the hardest, but then things start to get better,” Cathy assures. It just needs to be experienced!”

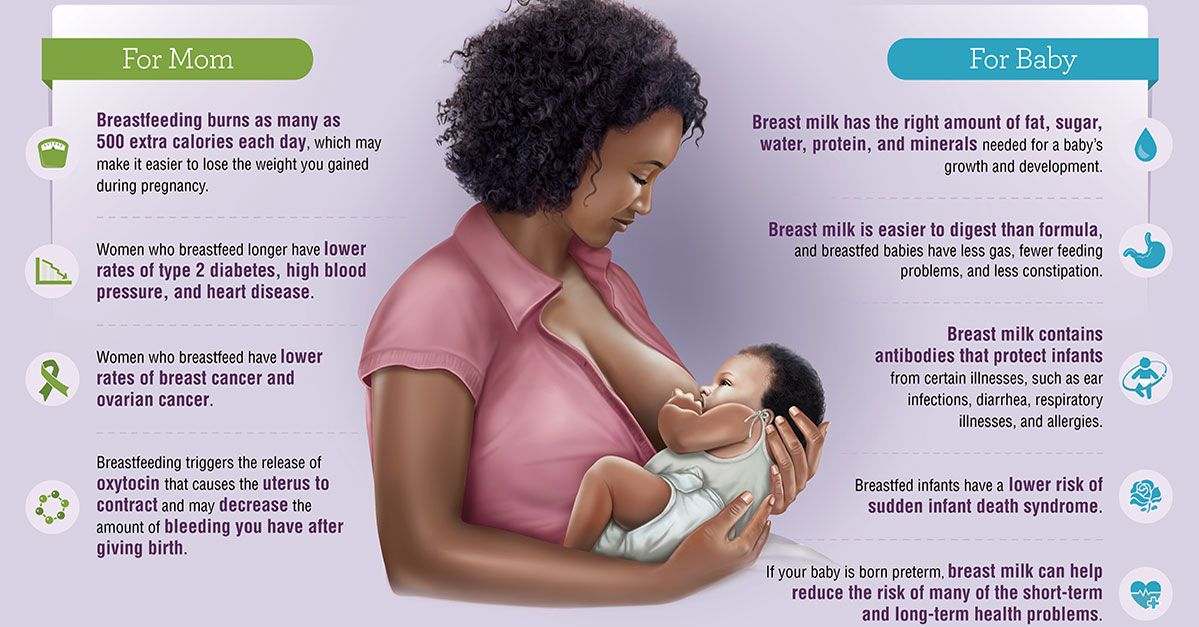

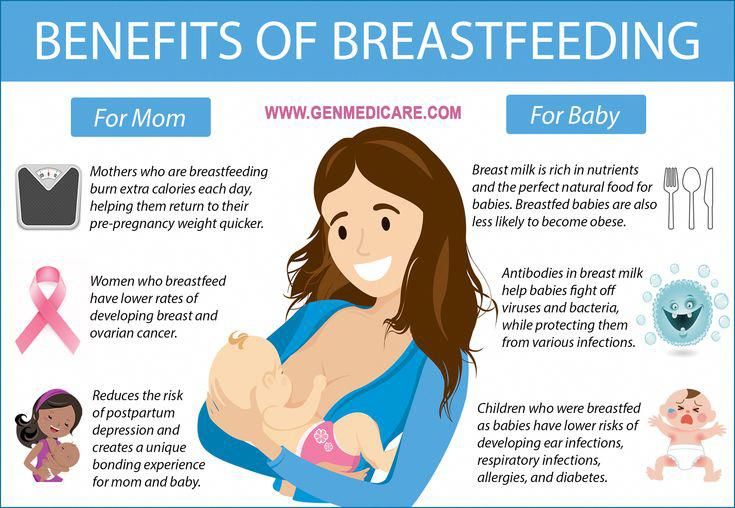

The longer breastfeeding continues, the more benefits it brings, from saving on formula and improving sleep quality 11–13 to boosting your baby's immune system 14 and reducing your risk of certain cancers. 15

“When you feel like you're pushing yourself, try to go from feed to feed and day to day,” says Hannah, a UK mom. “I was sure I wouldn’t make it to eight weeks. And now I have been breastfeeding for almost 17 weeks, and I dare say it is very easy.”

“I was sure I wouldn’t make it to eight weeks. And now I have been breastfeeding for almost 17 weeks, and I dare say it is very easy.”

Read the resource Breastfeeding Beyond the First Month: What to Expect

Literature

1 Naveed M et al. An autopsy study of relationship between perinatal stomach capacity and birth weight. Indian J Gastroenterol .1992;11(4):156-158. - Navid M. et al., Association between prenatal gastric volume and birth weight. Autopsy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1992;11(4):156-158.

2 Neville MC et al. Studies in human lactation: milk volumes in lactating women during the onset of lactation and full lactation .Am J Clinl Nutr . 1988;48(6):1375-1386. at the beginning and at the peak of lactation." Am F Clean Nutr. 1988;48(6):1375-1386.

3 Kent JC et al. Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet , Gynecol , & Neonatal Nurs . 2012;41(1):114-121. - Kent J.S. et al., "Principles for Maintaining and Increasing Milk Production". J Obstet Ginecol Neoneutal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114-121.

Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet , Gynecol , & Neonatal Nurs . 2012;41(1):114-121. - Kent J.S. et al., "Principles for Maintaining and Increasing Milk Production". J Obstet Ginecol Neoneutal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114-121.

4 Australian Breastfeeding Feeding cues ; 2017 Sep [ cited 2018 Feb ]. - Australian Breastfeeding Association [Internet], Feed Ready Signals; September 2017 [cited February 2018]

5 Kent JC et al. Response of breasts to different stimulation patterns of an electric breast pump. J Human Lact . 2003;19(2):179-186. - Kent J.S. et al., Breast Response to Different Types of Electric Breast Pump Stimulation.![]() J Human Lact (Journal of the International Association of Lactation Consultants). 2003;19(2):179-186.

J Human Lact (Journal of the International Association of Lactation Consultants). 2003;19(2):179-186.

6) Kent JC et al . Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3): e 387-395. - Kent J.S. et al., "Amount and frequency of breastfeeding and fat content of breast milk during the day." Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2006;117(3):e387-95.

7 Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical profession. 7th ed. Maryland Heights MO, USA: Elsevier Mosby; 2010. 1128 p . - Lawrence R.A., Lawrence R.M., "Breastfeeding: A guide for healthcare professionals." Seventh edition. Publisher Maryland Heights , Missouri, USA: Elsevier Mosby; 2010. P. 1128.

8 World Health Organization. [Internet]. Child growth standards; 2018 [cited 2018 Feb] - World Health Organization. [Internet]. Child Growth Standards 2018 [cited February 2018].

[Internet]. Child growth standards; 2018 [cited 2018 Feb] - World Health Organization. [Internet]. Child Growth Standards 2018 [cited February 2018].

9 Australian Breastfeeding Association . [ Internet ]. Cluster feeding and fussing babies ; - Australian Breastfeeding Association [Internet], Cluster Feeding and Screaming Babies; December 2017 [cited February 2018].

10 Moberg KU, Prime DK. Oxytocin effects in mothers and infants during breastfeeding. Infant . 2013;9(6):201-206.- Moberg K, Prime DK, "Oxytocin effects on mother and child during breastfeeding". Infant. 2013;9(6):201-206.

11 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [Internet]. Surgeon General Breastfeeding factsheet; 2011 Jan 20 [cited 2017 Feb] - Department of Health and Human Services [Internet], "Breastfeeding Facts from the Chief Medical Officer", Jan 20, 2011 [cited Feb 2017]

12 Kendall-Tackett K et al. The effect of feeding method on sleep duration, maternal well-being, and postpartum depression. clinical lactation. 2011;1;2(2):22-26. - Kendall-Tuckett, K. et al., "Influence of feeding pattern on sleep duration, maternal well-being and the development of postpartum depression." Clinical Lactation. 2011;2(2):22-26.

The effect of feeding method on sleep duration, maternal well-being, and postpartum depression. clinical lactation. 2011;1;2(2):22-26. - Kendall-Tuckett, K. et al., "Influence of feeding pattern on sleep duration, maternal well-being and the development of postpartum depression." Clinical Lactation. 2011;2(2):22-26.

13 Brown A, Harries V. Infant sleep and night feeding patterns during later infancy: Association with breastfeeding frequency, daytime complementary food intake, and infant weight. Breast Med . 2015;10(5):246-252. - Brown A., Harris W., "Night feedings and infant sleep in the first year of life and their association with feeding frequency, daytime supplementation, and infant weight." Brest Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2015;10(5):246-252.

14 Hassiotou F et al. Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clin Transl immunology. 2013;2(4). - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

Clin Transl immunology. 2013;2(4). - Hassiot F. et al., "Infectious diseases of the mother and child stimulate a rapid leukocyte reaction in breast milk." Clean Transl Immunology. 2013;2(4):e3.

15 Li DP et al. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev . 2014;15(12):4829-4837. - Lee D.P. et al., "Breastfeeding and the risk of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies." Asia Pas J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4829-4837.

Breastfeeding your baby with special needs

If your baby has special needs and has difficulty latch-on, there are many other ways to breastfeed

Share this information

Breastfeeding is a serious stress for a baby.![]() This process involves 40 muscles in the lips, tongue, jaw and cheeks, as well as six cranial nerves 1 for coordinating sucking, swallowing and breathing.

This process involves 40 muscles in the lips, tongue, jaw and cheeks, as well as six cranial nerves 1 for coordinating sucking, swallowing and breathing.

If a baby has a congenital disorder or disease that affects these muscles or nerves, the baby may not be physically fit to breastfeed or may not be able to get enough milk while nursing. But this does not mean that your baby should be deprived of extremely healthy breast milk. Moreover, the protective properties of milk and useful substances in its composition are even more necessary for children with special needs.

“Breast milk contains many living cells and growth factors that help boost immunity and prevent inflammation,” explains Dr. Katsumi Mitsuno, Professor of Internal Medicine in Pediatrics, Koto Toyosu Hospital at Showa University, “It is important for infants with special needs to give breast milk to prevent infectious diseases and ensure optimal nutrition.”

“Children with congenital and neurological pathologies are more susceptible to respiratory 2. 3 and ear 4 infections and diseases of the gastrointestinal tract 5 and are also more likely to need surgery. Breast milk helps to protect the baby's body from infections and promotes recovery 6 ,” adds Dr. Mitsuno.

3 and ear 4 infections and diseases of the gastrointestinal tract 5 and are also more likely to need surgery. Breast milk helps to protect the baby's body from infections and promotes recovery 6 ,” adds Dr. Mitsuno.

Reasons your baby may have difficulty breastfeeding

Cleft lip and/or palate

breastfeeding or supervising physician can show several helpful tricks. Newborns with cleft palate are often unable to breastfeed with sufficient force. 7

Prematurity

If the baby was born prematurely, he may be too weak and not have enough coordination to suckle effectively. Read more about this in the article on breastfeeding premature babies.

Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities

Babies with Down syndrome typically have problems with muscle tone and mouth-tongue coordination that prevents effective breastfeeding. 8 Other chromosomal disorders, such as Edwards syndrome or Patau syndrome, also make breastfeeding difficult.

8 Other chromosomal disorders, such as Edwards syndrome or Patau syndrome, also make breastfeeding difficult.

Neurological disorders

Neurological disorders (disorders of the brain, spine or nerves) often cause hypotonia, the medical term for low muscle tone. Cerebral palsy, 9 hydrocephalus, birth asphyxia, spina bifida, cerebral hemorrhage during childbirth, cerebral malformations and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy can cause difficulties in breastfeeding.

Pierre Robin's syndrome

With Pierre Robin's syndrome, the baby's lower jaw is much smaller than normal. Often this is combined with a cleft palate and tongue retraction, making breastfeeding almost impossible. 10

Maxillofacial surgery

If your baby has had oral, tongue or jaw surgery, it may be painful or uncomfortable to suckle for a while.

Expression of milk for children with special needs

Regardless of whether the baby can breastfeed, the first step is to start milk production in order to get enough milk. If the baby is unable to feed directly from the breast, it is important to ensure frequent pumping to collect as much milk as possible. It is necessary to start and stimulate the production of milk as early as possible so that the baby has enough of it now and in the future.

If the baby is unable to feed directly from the breast, it is important to ensure frequent pumping to collect as much milk as possible. It is necessary to start and stimulate the production of milk as early as possible so that the baby has enough of it now and in the future.

Double pumping is recommended about eight times a day as this is the best way to stimulate a steady supply of milk. 11 Seek help from your doctor or lactation consultant.

“For the first few months, my life revolved around pumping. I set an alarm and woke up every three hours at night to express milk,” recalls Katherine, a mother of two from New Zealand, “Michael had a cleft palate, so he couldn’t suckle, and we had to use a special squeeze bottle. When he ate, I did not take my eyes off him - as soon as I turned away, he could choke, or I did not notice how milk began to flow from his nose, which he did not like very much.

Participating in online support groups for mothers who only feed their babies with expressed milk has helped me a lot. I was able to express milk for my son for seven whole months - it was a real work in the name of love!”

I was able to express milk for my son for seven whole months - it was a real work in the name of love!”

Ways to breastfeed your baby

In some cases, your baby needs to be fed in a special way before he can breastfeed or bottle feed. For example, a feeding tube can be used to deliver milk directly into the baby's stomach. The tube is inserted by the attending physician, usually through the nose or mouth. As soon as the baby can eat in the usual way, the tube will be removed.

If the baby can swallow but is unable to breastfeed, alternative ways of feeding may be recommended. “For infants suffering from neurological disorders, you can use a drinking tube with a feeding tube or a special silicone nozzle on the finger, which an adult presses a finger against the palate. Some babies find it more convenient to eat with a special cup*, says Dr. Mitsuno. It all depends on the characteristics of the baby. Some people prefer drinking cups.”

“Cup cup feeding* is one of the most popular and safest ways to feed a baby who cannot breastfeed,” Dr. Mitsuno continues. you will be able to breastfeed your baby longer. Cup feeding usually spills quite a lot of milk, 12 and the amount spilled must be measured and taken into account if a specific amount of milk is recommended for an infant.”

Mitsuno continues. you will be able to breastfeed your baby longer. Cup feeding usually spills quite a lot of milk, 12 and the amount spilled must be measured and taken into account if a specific amount of milk is recommended for an infant.”

Sarah, a UK mother of three, recalls: “Our eldest daughter is a child with special needs. In particular, she has cerebral palsy. At first she suckled well at the breast, but on the third day her condition worsened, and until the age of two months she was fed expressed breast milk through a nasogastric tube. While she was in the hospital, I pumped milk every three hours.”

Sarah's story ended well: “At about eight weeks, my daughter's condition stabilized, and with the help of a specialist, we resumed breastfeeding. She switched to breastfeeding very easily. By the time she was 12 weeks old and we took her home, she was exclusively breastfed.

Although many people cared for our baby, pumping made me feel important, my special role. It helped me get through that incredibly difficult period.”

It helped me get through that incredibly difficult period.”

If your baby can latch on

If your baby has special needs but is physiologically able to latch on, offer the breast regularly along with other feeding methods. Even if he can't suckle milk from his breast, this "soothing" suckling will help him feel safe, warm, and cared for. It will also help your baby practice suckling skills, making it easier for him to transition to breastfeeding later on.

If your baby can breastfeed but is not getting enough milk, talk to your doctor about how much pumped milk you need to supplement and how best to give it. You can give your baby expressed milk while breastfeeding with a supplemental feeding system* or use one of the devices mentioned above.

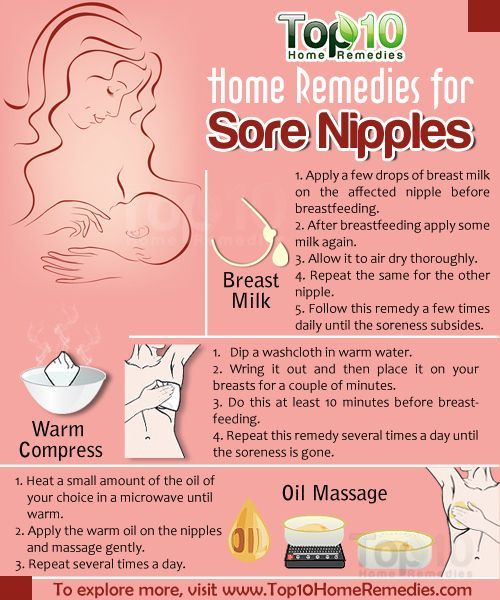

If your baby is recovering from maxillofacial surgery (eg for a cleft lip or palate), breastfeeding may be uncomfortable. However, offer your baby the breast along with other ways of feeding, according to some studies, sedative sucking can relieve pain. 13

13

“Everyone told me that because of the cleft lip, my son would not be able to breastfeed. But in fact, he was good at it, even though he injured my nipples while doing it,” recalls Nicola, a mother of three children from the UK, “After the operation, he was in pain at first, but soon everything returned to normal. He began to latch on very differently so it took us both some time to adjust, but pretty soon he was able to breastfeed normally and I breastfed him for up to a year.”

Literature

1 Walker M. Breastfeeding management for the clinician. 4th edition. Burlington, MA, USA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2016. 738 p. — Walker, M., Breastfeeding Considerations for Practitioners, 4th edition. Burlington, Massachusetts, USA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2016. Pp. 738.

2 Seddon PC, Khan Y. Respiratory problems in children with neurological impairment. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(1):75-78. - Seddon PS, Khan Y, "Respiratory problems in children with neurological deficits." Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(1):75-78.

- Seddon PS, Khan Y, "Respiratory problems in children with neurological deficits." Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(1):75-78.

3 Proesmans M. Respiratory illness in children with disability: a serious problem?. Breathe. 2016;12(4): e 97. - Proesmans M., "Respiratory diseases in children with disabilities: a serious problem?" Breeze (Breath). 2016;12(4):e97.

4 Zeisel SA, Roberts JE. Otitis media in young children with disabilities. Infants Young Child. 2003;16(2):106-119. - Zeisel SA, Roberts JI, "Otitis media in young disabled children". Infants Young Children. 2003;16(2):106-119.

5 González DJ et al. Gastrointestinal disorders in children with cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental disabilities. An Pediatr (Barc). 2010;73(6):361. - Gonzalez D.J. et al., Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children with Cerebral Palsy and Neurological Diseases. An Pediatrician (Bark). 2010;73(6):361.

An Pediatrician (Bark). 2010;73(6):361.

6 Salvatori G et al. Human milk and breastfeeding in surgical infants. Breastfeed Med . 2014;9(10):491-493. - Salvatori J. et al., Breast milk and breastfeeding in children undergoing surgery. Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2014;9(10):491-493.

7 Reilly S et al. ABM Clinical Protocol# 17: Guidelines for breastfeeding infants with cleft lip, cleft palate, or cleft lip and palate, Revised 2013. Breastfeed Med . 2013;8(4):349-353. - Reilly S. et al., AVM Clinical Protocol #17: Guidelines for breastfeeding children with cleft lip, cleft palate, or cleft lip and palate, 2013 edition. Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2013;8(4):349-353.

8 Thomas J ABM Clinical Protocol #16: Breastfeeding the Hypotonic Infant, Revision 2016. Breastfeed Med 2016;11(6). - Thomas J. et al., AVM Clinical Protocol #16: Breastfeeding a Baby with Reduced Muscle Tone, 2016 Revision. Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2016;11(6).

Breastfeed Med 2016;11(6). - Thomas J. et al., AVM Clinical Protocol #16: Breastfeeding a Baby with Reduced Muscle Tone, 2016 Revision. Brestfeed Med (Breastfeeding Medicine). 2016;11(6).

9 Wilson EM, Hustad KC. Early feeding abilities in children with cerebral palsy: a parental report study. J Med Speech Lang Pathol. 2009: nihpa 57357. - Wilson I.M., Khustad K.S., "Early independent feeding ability in children with cerebral palsy: a study of parent reports". J Med Speech Lang Patol. 2009: nihpa 57357.

10 Nassar E Feeding-facilitating techniques for the nursing infant with Robin sequence. Cleft Palate 2006;43(1):55-60. - Nassar, I. et al., Feeding Ease Techniques for Babies with Robin Syndrome. Kleft Palet Kraniofak J. 2006;43(1):55-60.

11 Kent JC Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal 2012;41(1):114-121. - Kent J.S. et al., "Principles for Maintaining and Increasing Milk Production". F Obstet Ginecol Neoneutal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114-121.

12 Dowling DA et al. Cup-feeding for preterm infants: mechanics and safety. J Hum Lact 2002;18(1):13-20. - Dowling D.A. et al., "Cup feeding preterm infants: technique and safety issues". G Hum Lakt. 2002;18(1):13-20.

13 Harrison D et al. Breastfeeding for procedural pain in infants beyond the neonatal period. Cochrane Database of 2014;10: CD 11248 - Harrison D.