How long do you bottle feed a baby calf

How Often to Feed – ProviCo Rural

Bottle-Feeding Calf Basics: How Often to Feed

While plenty of baby calves are able to meet their nutritional needs through their mother, it’s common to come across calves who have been rejected by or separated from their mother. When this happens, it’s necessary to bottle-feed the calf to ensure it receives the proper nutrients.

If you’re searching for ways to grow your herd, raising a bottle-fed calf is a great alternative to purchasing older cattle. Bottle-feeding takes time, effort, and dedication, but it is well worth it. It costs significantly less to buy a calf, the bottle-feeding stage is over extremely quickly, and bottle-fed calves often grow up into gentle, friendly, and companionable adults.

Bottle-feeding isn’t rocket science, but it does have some guidelines. We’ll lay them all out below so that you can learn the best practices of bottle-feeding calves for them to grow up healthy, strong, and happy.

How Often Do Newborn Calve Drink?

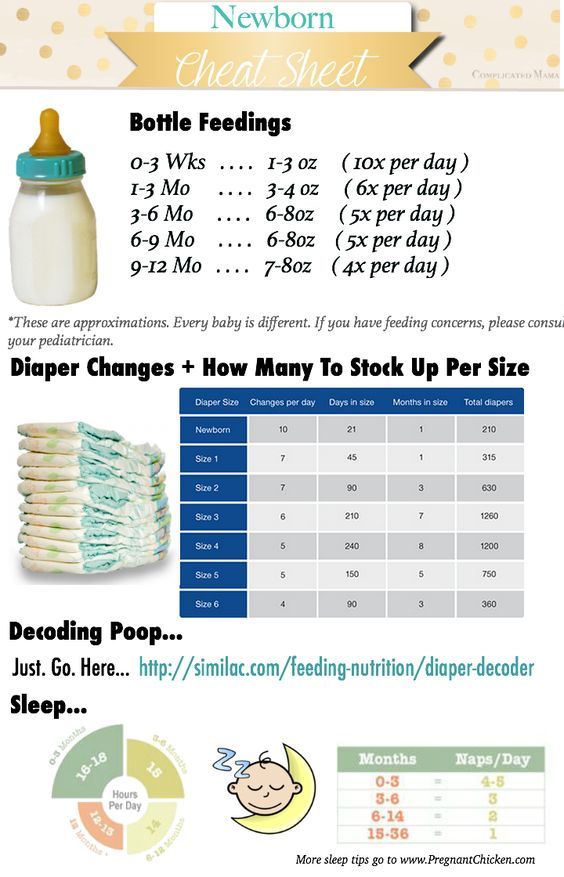

When nursing from their mothers, young calves will drink between 7 to 10 times a day, though their meals will be fairly small.

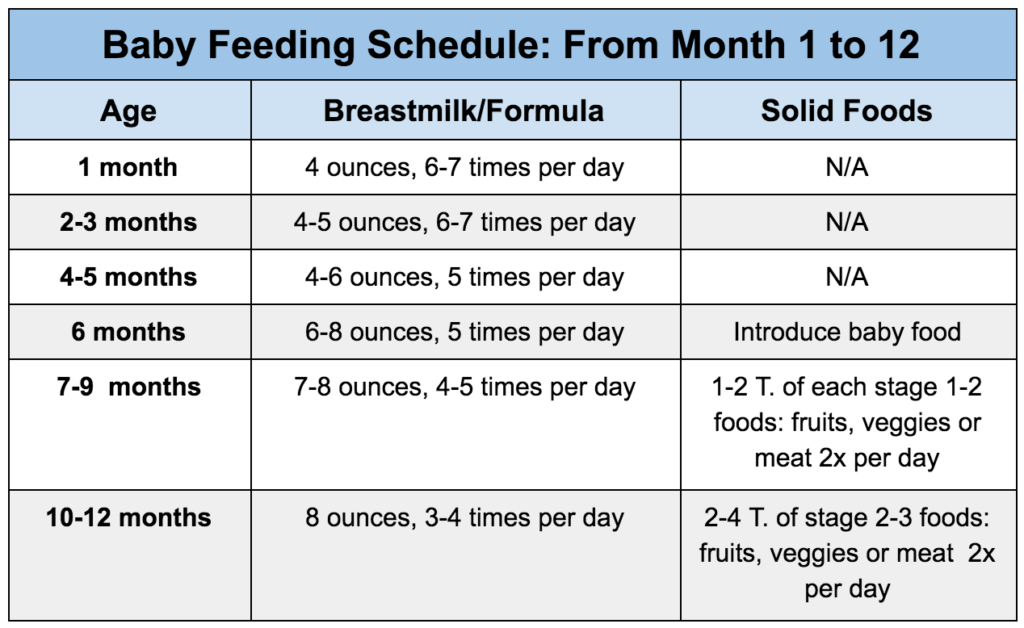

If you’re thinking that there’s no way you can do so many feedings every day, that’s OK! Bottle-fed calves only require 2 to 3 feedings a day — and that’s a much more manageable number. Your bottle-fed calf should only need two bottles as long as they’re kept warm and healthy. If they begin to lose weight or if it is cold, add an extra bottle to help them thrive.

Young calves require routine, so it is important to develop a feeding schedule right away and then stick to it. If you need to make any changes to your calves’ diet — such as adding new foods or reducing their milk replacer intake — do so gradually over the course of a week.

The Main Danger of Overfeeding a Newborn Calf

Bottle-fed calves often don’t know when to stop eating, making it easy to overfeed them. It’s imperative to stick to your feeding schedule to ensure your calf does not overdrink! Not only is overdrinking expensive, but it can also be dangerous — even deadly — for your calf.

Overfeeding your calf can result in scours, a type of cattle diarrhea, which can quickly cause dehydration, lethargy, low body temperature, and eventually death.

The key to treating scours is to do so as quickly as possible. Scours can often be treated with electrolyte mix, but these will only work if you take action before it’s too late. Select an isotonic electrolyte for best results.

While bottle-feeding your calf, be sure to monitor them for extremely loose, discolored, or bloody stool. If your calf develops scours or you notice something amiss, don’t hesitate to call the vet right away.

Tools Needed to Bottle-Feed Calves

There are a few items you’ll need to bottle-feed your calf correctly. All are relatively inexpensive and easy to find at most feed stores.

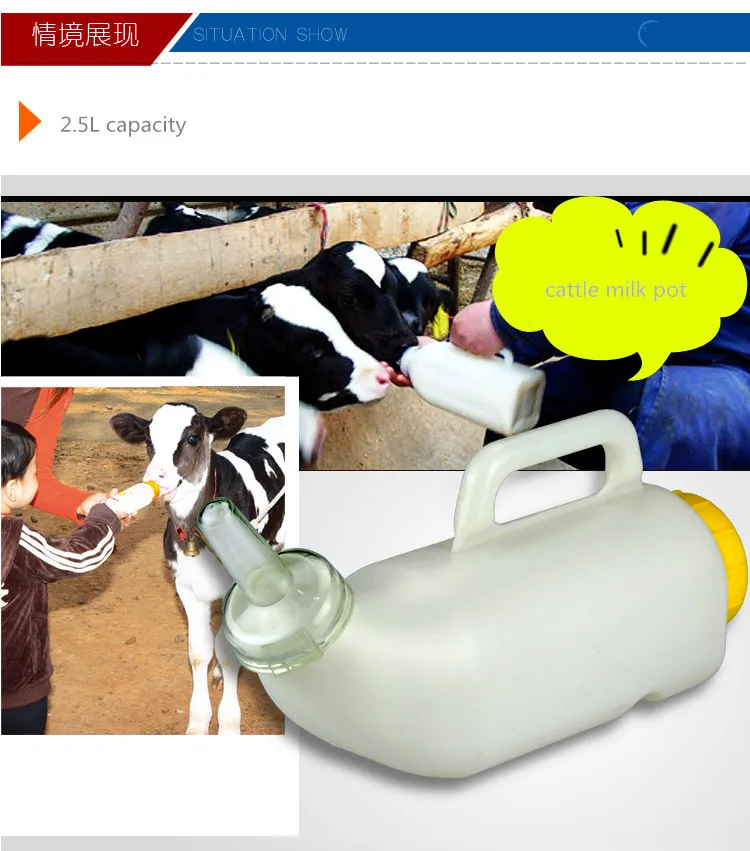

- Bottles and nipples. Calf bottles usually come in 2 liter measurements, the size of a standard meal. Nipples come in a variety of sizes and flows. Though most calves will drink from standard sizes without a problem, you may have to test a few for more picky drinkers.

- Thermometer. A thermometer will help you measure water temperature to ensure it is hot enough for the fats in the milk replacer to dissolve properly, but not too hot to cause the proteins to separate or to burn the calf.

- Whisk or mixer. A cheap whisk or other mixers will help you easily combine the water and mixer to ensure a smooth consistency.

- Mixing containers or buckets. Mixing containers or buckets with spouts will make pouring easier and less messy. And because it’s important to measure correctly, we recommend using a container with graduated measurements to ensure you’re always feeding the calf a consistent amount.

- Milk replacer. You’ll find many different types of milk replacer on the market, including medicated and non-medicated options. Your chosen milk replacer should come with clear instructions on how much to feed your calf. Make sure to follow these instructions as the amount of milk replacer to use per feeding may vary from brand to brand.

It’s incredibly important to keep your tools clean, sanitized, and dry when you’re not using them. Bacteria love the sugar content and temperature of milk and milk replacer and so will grow quickly on dirty containers, nipples, mixing buckets, and other equipment. Always clean and sanitize your bottle-feeding tools immediately after use to keep your calf healthy and stop the spread of bacteria to the rest of your herd.

How to Bottle-Feed a Calf in 8 Simple Steps

Now that you know how often to feed and the tools needed for a bottle feed, it’s time to learn the best way to bottle-feed! While it may take a few tries to perfect your system, bottle-feeding is actually fairly easy and quick.

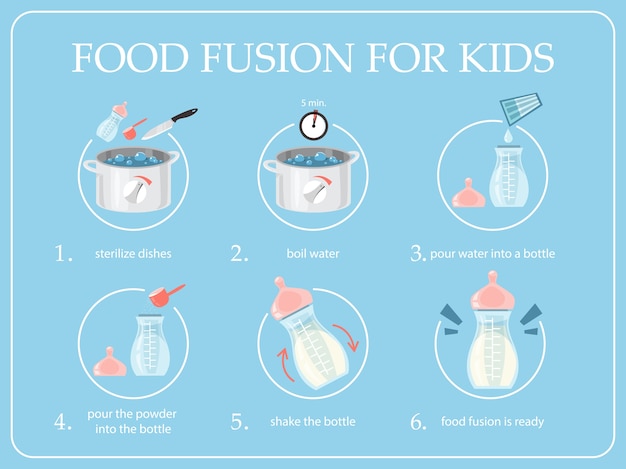

- Thoroughly wash your hands and gather your clean, sanitised and dry tools.

- Add half of the total amount of cleanwater to the mixing bucket or container, making sure that the temperature is between 40 to 50 degrees Celsius.

- Weigh out the proper amount of calf milk replacer powder and add to the mixing container.

- Stir for 1 to 3 minutes until the mixture is properly combined. There shouldn’t be any floating powder or spots when mixed thoroughly.

- Add the remaining clean water and mix again. The final temperature should be around 40 to 42 degrees Celsius when fed to the calf.

- Transfer the made-up liquid milk to the bottle and snap on the nipple.

- Feed the calf! Young calves may instinctually try to head-butt your hand or the bottle, so be sure to hold the bottle steady while feeding.

- Once the calf is done feeding, thoroughly clean, sanitise and air-dry all of your feeding tools. Store them in a clean and convenient location to facilitate the next feeding.

What Should I Feed a Bottle-Fed Calf?

Your bottle-fed calf will need a variety of foods for a healthy, wholesome diet.

If you receive your calf the day they’re born, their first feeding should be colostrum or a colostrum replacement. Colostrum is the first milk a nursing cow produces and is rich in antibodies, and other necessary bioactive elements that will protect the newborn calf from sickness and infections.

After the initial colostrum feeding, calves should be fed up to 2 liters of milk replacer two to three times a day. This will continue until the calf is at least 8-12 weeks old. As the calf grows, you can begin to supplement milk replacer feedings with hay, calf pellets, and pasture. Be sure to constantly provide the calf with clean water.

Choosing the right milk replacer is essential to your calves’ health and growth. It is important to note that most healthy calves reared in small numbers do not need a medicated milk replacer. For intensive calf-rearing operations where the risk of disease is often high, use medicated milk replacers for best results. Avoid rearing calves from saleyards. Interested in supplements for your livestock? Look for high-quality, affordable, and fortified formulas such as ProviCo Rural’s formulas to ensure your calf gets the best start in life.

Instructions for Raising Bottle Calves – Mother Earth News

So you want to raise a small herd (maybe just two or three head) of cattle and enjoy honest-to-goodness “homegrown” milk, cream, butter, yogurt, cottage cheese, ice cream, and/or beef for a change? But you don’t have the time, money, acreage, or know-how to start right out with several full-grown animals? Then here’s a suggestion: Why not start small … by raising bottle calves?

Ken and I acquired our very first herd this way more than 10 years ago. Since then, we’ve ”mothered” a good many bottle calves (and learned a great deal through trial and error). And we’re still convinced that the ”bottle method” is by far the easiest, most economical, most educational way to get started in small-scale dairy farming or beef raising.

Since then, we’ve ”mothered” a good many bottle calves (and learned a great deal through trial and error). And we’re still convinced that the ”bottle method” is by far the easiest, most economical, most educational way to get started in small-scale dairy farming or beef raising.

Where to Buy Bottle Calves

Whenever possible, Ken and I buy our calves directly from the original owner, and we recommend that you do the same. Check with local dairies which frequently sell some of their calves at birth. (An advantage of buying from a dairy is that sometimes the calf has been allowed to nurse for a few days, in which case the calf has already gotten a good dose of the colostrum — or first milk — it needs for a good start in life.) While you’re at the dairy, ask about buying some fresh colostrum too (even if they have no calves to sell you). A couple plastic jugfuls of colostrum kept at home in the freezer can come in handy later on.

You can sometimes also purchase calves at feedlots, since — frequently — cows that are brought to the lots for fattening are pregnant, and the managers of the operations don’t want to bother with infants. Quite often, too, a calf born in one of these huge “meat factories” will get very little care (perhaps not even a first feeding). Hence, you may want to ask someone who works at a feedlot to notify you immediately when a calf is born.

Quite often, too, a calf born in one of these huge “meat factories” will get very little care (perhaps not even a first feeding). Hence, you may want to ask someone who works at a feedlot to notify you immediately when a calf is born.

We also buy calves now and then from the local livestock auction buy only if we feel we have the time, money, and extra pens to gamble with. (The sad truth is, you never really know what you’re getting when you buy an animal at auction.) If you decide to go to one of the sales, try to arrive several hours before the bidding starts and don’t buy any calf that you can’t check close-up first.

What does a calf cost? Well, the current price in 1978 for day-old calves in this area (Broadwater, Nebraska) is about $50. Calves from milker stock can still be bought at auction for about $25, however. (Last spring, I purchased eight little ones at auction for an average of $10 each. Four turned out to be “hot calves” [see below] and died the first week … while the other four grew well and netted us a nice return in the fall. )

)

What to Look for in a Calf

Before Ken and I purchase any calf, we check it over very carefully. First, we stand the animal up and run our hands over its body to check for swellings, enlarged bones, and deformities. (We also put an ear to the calf’s rib cage to try to detect lung problems.)

Next, we check the baby’s navel for signs of infection. Navel ill — a troublesome malady that afflicts newborns whose umbilical cords haven’t been clipped (or sterilized) properly — is difficult to treat once it takes hold since the infection spreads rapidly throughout the body. Better to discover it now than later.

Finally, we give the prospective purchase a good “once over” to see that the infant’s eyes are bright and clear (no clouds or white spots), its ears are up and alert (not drooped), and its nostrils are free of any discharge. We also put the animal to the “finger test”: A healthy calf will usually suck your finger. (If the calf squirms or pulls away when you perform this — or any other test, consider it a good sign. A sick or poor-quality calf is usually overly docile.)

A sick or poor-quality calf is usually overly docile.)

How to Avoid Buying a ‘Hot Calf’

Calves born in feedlots should be examined very carefully before any money changes hands. Many (if not most) of the lots put their cattle on a diet high in concentrates and additives — feed that makes the animals gain a great deal of weight very quickly — but that can leave the stomachs and intestines of unborn calves badly “burned.” Such burned infants are known in the trade as hot calves.

Hot calves rarely live more than a few weeks since they cannot absorb food. Therefore, it’s imperative that you determine whether the feedlot calf you’re thinking of buying is ”hot” before you commit yourself to the purchase.

Open the calf’s mouth and smell its throat. If the mother was on hot feed, the odor will be sour-sweet and very strong (somewhat like rotten ensilage). Also check the animal’s gums: They may be blue-tinged, or even bloody. In general, you’ll find that a hot calf is listless, has droopy ears and dull eyes (eyes that may also show white “burn” spots), and prefers to lie tightly curled in a fetal position.

If the calf you’re looking at displays any of the above symptoms, save your money and move onto the next one.

Keep Your Future Bottle Calf Dry and Warm

You can’t buy an already-stressed calf, haul it 30 miles in the back of a pickup in cold weather, and expect the animal to survive (much less thrive). Some provision must be made for keeping the calf dry and warm from the time you buy it until you can get it home to a draft-free pen.

Whenever Ken and I go out to buy a calf, we always (even if it’s only a little chilly) drive through an alley behind a nearby appliance store and [1] pick up a large cardboard crate (the kind that stoves and freezers come in), [2] put some straw in the box, and [3] set the container in the truck. (We also carry an old quilt with us to wrap the animal in, since calves are usually wet and/or muddy at the time of sale.) Then we’re ready to tuck our new calf into a nice, comfortable, sheltered environment for the trip home.

When we arrive back at the farm, we immediately isolate the new calf from the rest of our herd. (It’s easier than you think to wipe out a large portion of an existing herd — one that you’ve spent a lot of time building up — by bringing in a strange calf that harbors disease germs.) Then — as an added precaution — we change our clothes and shoes before doing any chores. (A good many diseases can be carried home from an auction — or a feedlot — on the soles of boots.)

(It’s easier than you think to wipe out a large portion of an existing herd — one that you’ve spent a lot of time building up — by bringing in a strange calf that harbors disease germs.) Then — as an added precaution — we change our clothes and shoes before doing any chores. (A good many diseases can be carried home from an auction — or a feedlot — on the soles of boots.)

About housing: A simple three-sided lean-to (measuring, say, 4-by-5 feet) built against the side of a shed or garage will suffice to keep your calf out of the cold. Or you can build a freestanding structure. Just [1] plant four posts in the ground, [2] nail 2-by-4s between the tops (and the bottoms) of the uprights, [3] fasten old boards (or what you have) to the structure’s sides, and [4] cover the top with chicken wire and a layer of straw or hay (plus — maybe — an old flap of canvas that can be let down over the front during really nasty weather).

For his first few days at home, we like to make sure our new calf is dry, warm, and comfortable. That means plenty of straw or hay for bedding and if the weather is cold, a heat lamp for extra coziness (since the infant doesn’t have its mother around to help keep it warm). And do keep the calf both warm and dry, with the emphasis on that last word. (Calves can actually withstand below-zero temperatures easily if they’re dry. Wet and cold — on the other hand — are two of the surest invitations to scours I can think of.)

That means plenty of straw or hay for bedding and if the weather is cold, a heat lamp for extra coziness (since the infant doesn’t have its mother around to help keep it warm). And do keep the calf both warm and dry, with the emphasis on that last word. (Calves can actually withstand below-zero temperatures easily if they’re dry. Wet and cold — on the other hand — are two of the surest invitations to scours I can think of.)

Feeding Time

Once your calf is established in his new quarters, it’s time to feed him. For this, you’ll need a couple of calf bottles (which you can obtain at any feed store or veterinary supply house). These bottles hold two quarts each and are preferable — in my opinion — to “nipple buckets.”

If the calf is only a few hours old and hasn’t had its first meal with mama, you’ll want to feed the calf warm (i.e., body-temperature) colostrum … a quart of it, if he’ll drink that much. Without at least one feeding of this precious fluid (which is rich in proteins, minerals, vitamins, and disease-fighting antibodies), the calf’s chances of survival are greatly reduced.

In the event fresh (or frozen) colostrum isn’t available, you can concoct a satisfactory “colostrum replacer” as follows: First, mix together 2 eggs, 1 tablespoon of honey, ½ teaspoon of powdered A, D, and E vitamins (I use Pfizer’s water-soluble A,D, and E), and 1 cup of bovine milk replacer (available from the feed store). Stir this mixture into 1 quart of warm water and administer it in 1 quart quantities for the calf’s first 2 feedings.

As soon as our new calf has had his first feeding, we give him a shot of A, D, and E vitamins to help him along. (A small bottle of liquid A, D, and E will cost you $5.00, but it’ll treat many calves and will be well worth the money.) We inject ½-cc of the vitamins (using a small needle and syringe) intramuscularly in the fleshy part of the calf’s rump. Afterwards, we follow up with a ½-cc shot of Combiotic — again given intramuscularly — either in the opposite hip or the shoulder. (Combiotic contains penicillin and dihydrostreptomycin … antibiotics that will help stave off any infections that may have gotten started in the sale yard, on the ride home, etc. )

)

After the calf’s first two feedings, switch from colostrum to high-quality milk replacer. The key words here are high-quality. Don’t buy the cheapest milk replacer you can find unless its contents are the same as the more expensive mixes. (Check the protein and fat content on the bag. Some replacers have a protein count of only 12 ½ percent, which is much too weak. You want a protein level of at least 25 percent.)

Instructions for mixing bovine milk replacer come on the sack. You may want — as I do — to make the fluid a little richer for the first few weeks by putting a well-beaten egg into every two quarts of replacer. (This adds food value and makes the calf’s eye and coat shine.) A little honey in the mix will help combat constipation.

How often — and how much — should you feed your bottle calf? Some folks say to feed one quart twice a day at first. But I prefer to give our calves each one quart three times a day for their first two weeks … then two quarts twice daily until the fourth month, by which time the young calf should be eating mainly solid food. (See the accompanying “Feeds and Feeding” section near the end of this article.)

(See the accompanying “Feeds and Feeding” section near the end of this article.)

What to Do if Your Calf Refuses Its Bottle

Sometimes (especially if the calf has already grown accustomed to nursing his mother) a perfectly healthy calf will refuse the bottle. I find that the easiest way to get a reluctant calf to eat in such a case is to [1] fill the bottle with milk that’s nice and warm, [2] stand astraddle the calf, holding him firmly between your knees, [3] lean forward until your chest is over its head, and [4] place the bottle in the calf’s mouth. Of course if the calf is particularly husky, you’ll have to watch that he doesn’t throw his head up quickly and bump you in the chest. This method has, however, always worked well for me (maybe because the calf thinks he is under his mother and feels secure).

After a couple of feedings by the “overhead” method described above, you should be able to hold the bottle through the fence and feed the calf in the normal way. (For me, the “normal way” includes lots of chatter: I always talk to our calves while I feed them. They quickly grow accustomed to my voice and seem to grow much better.)

(For me, the “normal way” includes lots of chatter: I always talk to our calves while I feed them. They quickly grow accustomed to my voice and seem to grow much better.)

Weaning to Solid Food

At the end of their first week, I put fresh water out for our calves and offer them a good-quality, leafy hay or some alfalfa. Some calves won’t eat much at first, but they should be offered the food anyway.

At two weeks, I begin to offer each baby calf starter pellets (available from any feed store). The calves may hesitate to eat these at first, but you can “help them along” by putting a few pellets in their mouths after every bottle feeding. (The sooner the calves begin to eat solid foods, the sooner you can quit messing with the bottle.)

I try to have my calves off the bottle by the time they’re four months old. (For the last two weeks, I feed each one only one bottle a day.) From the third week on, I keep a block of salt in their pen and watch the calves carefully so that they don’t eat too much of it.

As the calves grow, they’ll generally do well on a diet of good hay or alfalfa, ground corn, oats, soybean meal, salt, and (always) plenty of freshwater. (See “Feeds and Feeding” later in this article.)

Nutritional Difficulties (and How to Avoid Them)

Fortunately, the so-called nutritional diseases of cattle are seldom fatal, but they can cause substantial financial loss due to slow weight gain (not to mention a great deal of unhappiness on the part of your animals). Therefore, it pays to know what these diseases are and how to spot them.

Usually — if a good quality of grass, silage, or alfalfa and grain is available — a calf won’t need any supplements once it has started to eat solid foods. Occasionally, though, the available grain won’t have the vitamin content it should have (even the best hay will lose its food value if it’s allowed to get wet or moldy, or deteriorate), and your calves can begin to develop vitamin A and/or D deficiencies.

Vitamin A deficiency is characterized by rapid breathing, stiffness, weight loss, appetite loss, swelling of joints, and (sometimes) convulsions. The calf may begin to show improvement within minutes after a shot of A, D, and E, if the problem is acute. Occasionally, however — if the animal’s been on poor-quality feed — two vitamin shots a week apart will be necessary to get the calf back on its feet. (Moral: If you suspect poor-quality hay or grain, watch for signs of vitamin A deficiency.)

The calf may begin to show improvement within minutes after a shot of A, D, and E, if the problem is acute. Occasionally, however — if the animal’s been on poor-quality feed — two vitamin shots a week apart will be necessary to get the calf back on its feet. (Moral: If you suspect poor-quality hay or grain, watch for signs of vitamin A deficiency.)

Although cattle of all ages can suffer from a lack of vitamin A, younger animals are particularly susceptible (especially those that are fed skim milk rather than a high quality milk replacer). Newborn calves are the most vulnerable, since they do not have a reserve supply of the vitamin in their bodies. For this reason, I give my calves a shot of A, D, and E vitamins after their first feeding. (I also add a little powdered A, D, and E to their milk or water once or twice a month, for added insurance.)

Vitamin D is required by calves for the proper absorption of calcium and phosphorus. Without it, the animals can develop rickets and/or bumpy knees. One to two pounds of sun-cured alfalfa per day, however, will prevent rickets in calves up to 195 days old, so the deficiency isn’t difficult to cure. The time to watch most sharply for vitamin D deficiency is winter when animals don’t get much direct sunlight.

One to two pounds of sun-cured alfalfa per day, however, will prevent rickets in calves up to 195 days old, so the deficiency isn’t difficult to cure. The time to watch most sharply for vitamin D deficiency is winter when animals don’t get much direct sunlight.

If your calves start to chew on bones, rocks, wood, etc., they may not be getting enough calcium in their diets. A good way to supply calcium is to add 40 pounds of finely ground limestone to each ton of grain.

It’s also possible — if a calf is fed for too long on milk without forage or grain — that the animal may become nervous and irritable and lose its appetite. In this case, the calf is probably suffering from a magnesium deficiency. (There’s enough magnesium in most forage and grain to ensure that this condition seldom occurs if the calf is eating solid food.) Legumes, grass hay, soybean meal, wheat bran, and beet pulp are all rich in magnesium.

Among dietary minerals, iodine is particularly important since goiters can grow in the throat of an iodine-deficient calf and choke the animal. In some iodine-scarce areas (and that includes sections of almost all states west of the Mississippi), this mineral must be added to calves’ (and people’s) diets on a routine basis. Fortunately, this is easy to do: Simply buy iodized — instead of plain — salt for your animals.

In some iodine-scarce areas (and that includes sections of almost all states west of the Mississippi), this mineral must be added to calves’ (and people’s) diets on a routine basis. Fortunately, this is easy to do: Simply buy iodized — instead of plain — salt for your animals.

Speaking of salt, calves should consume about a quarter- to a half-ounce of sodium chloride per animal per day. If the calves don’t get their daily salt, they’ll sometimes overeat and become ill. Always keep a block of salt where the calves can get at it easily.

One nutrition-related disease that can endanger a calf’s life is grass tetany. This malady occurs when a calf that’s been confined to a small pen on rations of dry hay is suddenly turned out into a lush, green field. Among the ailment’s symptoms are twitching muscles, grinding teeth, unusual excitement, nervousness, and cramps. If the disease is not caught early enough, the period of excitement can be followed by paralysis, unconsciousness, and death … sometimes as quickly as 30 minutes after the first symptoms are noted.

Needless to say, grass tetany demands prompt treatment. Usually, intravenous administration of calcium chloride solution is recommended. (This is best handled by a veterinarian.)

None of our animals (luckily) have ever had grass tetany, but I have seen cattle in a pasture near our home die of the condition. Here — as always — an ounce of prevention is worth a pound (at least) of cure. Feed your young calves powdered minerals free choice for several weeks before turning them out into lush pastures, and then introduce them to the rich forage gradually. Also, watch for grass tetany if fields have recently turned green after a good rain.

The Most Dreaded Calf Disease of Them All: Scours

Scours (a kind of diarrhea) comes in a number of varieties: white, green, black, and bloody. The disorder can be brought on by any number of upsets, including exposure to wet and cold, overfeeding, contact with an infected animal, or a trip through the auction yard.

The disease begins with simple diarrhea. Unless this is stopped at once, the afflicted calf soon begins to pass yellowish, greenish, or light-brown (and in any case very foul-smelling) feces. At the same time, the calf becomes dull and listless, exhibits a below-normal body temperature (i.e., below 101 degrees to 103 degrees), experiences dehydration, and may pass bloody stools. Pneumonia, and death often follow.

Unless this is stopped at once, the afflicted calf soon begins to pass yellowish, greenish, or light-brown (and in any case very foul-smelling) feces. At the same time, the calf becomes dull and listless, exhibits a below-normal body temperature (i.e., below 101 degrees to 103 degrees), experiences dehydration, and may pass bloody stools. Pneumonia, and death often follow.

There are many scour remedies on the market. I have yet, however, to find one that’ll work well after the disease has become at all advanced, and I have yet to find one that will nip scours in the bud as well as the “home remedy” we’ve used for fifteen years: Whenever I notice that a calf is passing looser-than-usual feces, I skip the next feeding of milk. In its place, I feed a fluid made by mixing three tablespoons of pectin (Sure-Jell or Pen Jell) in a cup of warm water. (Although it tastes terrible, the calf will usually gulp down at least a cupful of the fluid from a bottle before it notices.)

Once the pectin finds its way to the animal’s digestive tract, it causes the stomach’s contents to jell and stops the cramping. (Of course, if you don’t feed the solution immediately after it’s prepared, the pectin will jell in the bottle instead of in the calf!)

(Of course, if you don’t feed the solution immediately after it’s prepared, the pectin will jell in the bottle instead of in the calf!)

An hour after the feeding of pectin-water, give the afflicted animal half its normal amount of milk, followed — an hour later — by another serving of pectin and water. If the condition doesn’t clear up in six hours, administer a shot of Combiotic. Also, add an egg to the baby’s milk at each feeding for a couple of days to give it extra strength.

What to Do About Lice

Although lice are seldom a problem during the warmer months of the year, cattle of all ages can (and often do) become lousy in the fall and winter. Frequently, the parasites are carried in by birds.

Four kinds of lice bother cattle. Three suck blood and the fourth eats skin and hair. All cause itching and a slowdown in growth rates.

If your mini-herd becomes infested with lice, make up a delousing medicine by mixing 1 ¾ pounds of rotenone and one-half pound of detergent with 25 gallons of water then spray your animals with the liquid twice: once now and again in five to 18 days. (The first bath kills mature lice and the second gets the newly hatched parasites — or “nits” — that weren’t killed by the initial spraying.) This treatment will also ward off cattle grubs.

(The first bath kills mature lice and the second gets the newly hatched parasites — or “nits” — that weren’t killed by the initial spraying.) This treatment will also ward off cattle grubs.

Dehorning Cattle

When you purchase a calf, ask its seller whether the animal is of a horned breed or a polled (hornless) breed. If the calf is the horned type — or if you can feel horn buttons poking through the calf’s scalp a few days after you’ve taken him home — you’ll want to dehorn the little calf as soon as possible.

The advantages of dehorning are many: The main one being safety. Hand-raised calves aren’t afraid of humans, and the tiny calf you’re rearing on a bottle will — when it grows to be a 1,000-pound cow or bull — think nothing of “nudging” you for attention now and then. If your pet still has horns at that time, those gentle nudges could well be painful … or dangerous. (I know: Several times, our bottle-raised herd bull has jolted me with his horns and made me realize how dumb I was to let him keep his horns when he was a little cutie. ) In addition, of course, horned cattle tend to hook each other at the feeding trough, get caught on fences, etc.

) In addition, of course, horned cattle tend to hook each other at the feeding trough, get caught on fences, etc.

The easiest way to prevent horns from appearing is to apply caustic potash (or a similar substance) to the calf’s horn buttons four to 10 days after birth or whenever you can feel horn buttons forming beneath the scalp. Caustic potash is available at drugstores in both pencil and paste forms. (CAUTION: Always wear gloves when you work with caustic potash.)

If you can feel a horn button just below the skin, scrape away the hair covering it and apply a thick layer of Vaseline to the area around the nub. Then cover the horn button itself with caustic potash. (The “burn” area should be about the size of a nickel.) Protect the animal from rain for the next six to eight hours or until a scab has begun to form. The scab should heal completely within a week to 10 days.

Castration

If you intend to raise a bull calf for beef, it’ll be necessary to castrate him. (Neutered males simply “dress out” better than bulls.) Many folks wait until their bulls are two or three months old to unsex them, but if the calf is strong and healthy, the operation may be performed a few days after birth. I find that two or three weeks is a good age, since the calf is still small enough for easy handling, yet large enough to withstand the stress of the operation.

(Neutered males simply “dress out” better than bulls.) Many folks wait until their bulls are two or three months old to unsex them, but if the calf is strong and healthy, the operation may be performed a few days after birth. I find that two or three weeks is a good age, since the calf is still small enough for easy handling, yet large enough to withstand the stress of the operation.

The three most-used methods of castration are [1] the lateral incision method (which is what we use on our farm), [2] the end incision method, and [3] bloodless (emasculatome) castration. (Each of these methods is described in detail in G.W. Stamm’s Veterinary Guide for Farmers, available for around $5 from Amazon.com. Ideally, castration should be done in early spring before the fly season gets underway, to minimize the danger of fly-borne infections … and — for your own safety — the animal being castrated should be restrained. If you’ve never done the operation before, have a veterinarian (or an experienced herdsman) help you the first time.

It’s Easier Than You Think to Raise Your Own Bottle Calves

If — in the preceding pages — I’ve given you the impression that raising bottle calves is an expensive and laborious undertaking fraught with pitfalls … believe me, it’s not. We’ve never regretted having a small herd of the calves around our farm: We’ve never felt bad, for instance, about having our own milk cow (hand-raised from the bottle stage), or our own beef in the freezer … and the money we get every fall for the calves that we sell as yearlings ($2,100 net last year) always comes in mighty handy.

I suppose if I had just two words of advice to give to someone who hasn’t yet raised a bottle calf, they’d be: First, try to get as good a calf as you can find (or afford) in the beginning. (Later on, you can try your hand at raising a so-called “bargain” calf.) Second, don’t wait any longer … do it. You have nothing (except a little time) to lose and a good deal of milk, cream, butter, yogurt, cheese, beef, extra income, and satisfaction to gain!

Feeds and Feeding

Birth to two weeks: Two one-quart feedings of colostrum the first day, then one quart of milk replacer three times a day. (Keep fresh water and alfalfa before the calves.)

(Keep fresh water and alfalfa before the calves.)

Two to eight weeks: Two quarts of milk replacer twice daily. Begin feeding calf pellets (the best you can buy). Put salt in pen and continue to make water and alfalfa available.

Eight to 12 weeks: Start mixing pellets with a ground feed made by combining ground corn, oats, and bran with a little powdered molasses. (Gradually increase the ratio of ground feed to pellets.) Feed two pounds of grain per day per calf, plus two quarts of milk replacer twice daily. Continue to offer salt, water, and alfalfa. (Good green pasture may be substituted for the alfalfa.)

12 to 16 weeks: Two quarts of milk replacer once a day. Offer access to good leafy forage or good grass. If you’re raising the calf for beef, you may increase the allotment of grain (mentioned above) … otherwise — if grass is very good — the calf can graze through the summer. (In summer, our calves get just pasture grass, iodized salt, free choice minerals, and water. )

)

Note: Excellent material on feeds and feeding is usually available free of charge through the county extension office. Check the county listings in the white pages of your phone book. — Luilla Thompson

Some Common Illnesses of Cattle

It goes without saying that when you acquire your first bottle calf, you should check with your county agent or veterinarian to determine which vaccines (if any) are recommended for cattle in your area … then have your calf vaccinated. This will take care of most of the important, life-threatening illnesses with which your calf may come in contact.

Unfortunately for the small holder, there are at least as many cattle ailments for which no vaccine exists as there are illnesses of the “immunizable” type. The following represent some of the more common “non-immunizable” illnesses that can afflict cattle of all ages.

Colds: I find that if one of my calves gets a runny nose or shows any other signs of a cold, a scaled-up dose of common aspirin (to bring down any fever) and a shot of Combiotic will usually knock the infection right out. In addition, if the animal has the chills and is shivering, I fix him a warm toddy consisting of ¼ cup of whiskey, 1 ounce of lemon juice, 2 teaspoons of honey, and 1/8 of a teaspoon of powdered A and D vitamins mixed in 1 cup of warm water.

In addition, if the animal has the chills and is shivering, I fix him a warm toddy consisting of ¼ cup of whiskey, 1 ounce of lemon juice, 2 teaspoons of honey, and 1/8 of a teaspoon of powdered A and D vitamins mixed in 1 cup of warm water.

Lead Poisoning: Lead kills far more farm animals than any other metal primarily because so many paints contain lead, and calves like to lick or chew on painted objects. The symptoms of lead poisoning include drooling, choking, trembling, and loss of appetite. A purgative dose of Epsom salts is the most common treatment. The best medicine, of course, is prevention: Simply keep your calves away from boards that have been treated with lead-based paints, and you won’t have to worry about lead poisoning.

Hardware Disease: It’s a fact: If nuts, bolts, nails, staples, and other small metallic objects are left around, they’ll often disappear into a calf’s stomach. This — in turn — gives rise to an illness known (appropriately enough) as “hardware disease,” the symptoms of which include pain and a lack of appetite that’s not accompanied by distension of the stomach. (In advanced cases, labored breathing is noticeable, but at that stage of the disease, there’s not much you can do.)

(In advanced cases, labored breathing is noticeable, but at that stage of the disease, there’s not much you can do.)

If hardware disease is suspected, a vet can place a magnet in the animal’s reticulum (second stomach). The magnet then remains in the stomach permanently and attracts nails, staples, etc. (which gather on the magnet rather than irritating the calf’s tissues).

To prevent hardware disease, keep your calves’ pens and grazing areas free of wire, nuts, bolts, screws, and other metallic objects.

Pinkeye: Pinkeye is quite common in baby calves and can afflict older cattle, too. While not a serious disease, pinkeye is highly contagious among cattle and does cause a great deal of discomfort. The main symptom is red, running eyes that sometimes cake shut. (In severe cases, a white blind spot may be left on the eye after the disease clears up … which is to say, in two or three weeks.)

There are several pinkeye medications on the market. When just one of a calf’s eyes is affected, you may want — in addition to applying medication — to tape a patch over the afflicted eye to protect it from sunlight and (possibly) keep the disease from spreading to the entire herd.

When just one of a calf’s eyes is affected, you may want — in addition to applying medication — to tape a patch over the afflicted eye to protect it from sunlight and (possibly) keep the disease from spreading to the entire herd.

Since flies transmit pinkeye from calf to calf, it’s important to keep the barn and pens clean to hold down the fly population. We’ve found that a good way to catch flies is to set out shallow pans containing a piece of meat (for bait) and a nicotine sulfate solution (one-half ounce of the sulfate per gallon of water). (Naturally, we make sure these pans are out of the reach of children and animals.)

Worms: Cattle can and do get worms, and there are numerous preparations on the market to kill the parasites. Here again, prevention (i.e., good management) is the best medicine. Feed your calves from racks or troughs (not right off the ground), give them a clean water supply, and rotate pastures often.

Bloat: If you walk out to the calf pen one morning and find that your little calf is swollen to twice his normal girth and has trouble breathing, chances are you’re looking at a case of bloat. If the calf is still on its feet, you may be able to alleviate the condition by giving the animal a pint of mineral oil (make sure the oil gets into the stomach, not the lungs) or by making the calf walk around for a while.

If the calf is still on its feet, you may be able to alleviate the condition by giving the animal a pint of mineral oil (make sure the oil gets into the stomach, not the lungs) or by making the calf walk around for a while.

Many times, however, the bloated calf will already be down on the ground with its feet sticking straight out when you first come on the scene. In this case, there’s no time to lose: The calf’s abdominal cavity must be punctured immediately — either with a knife or a special device called a trocar — to release the trapped gases. (Otherwise, the calf may well die from a ruptured stomach or the shutting off of air to the lungs.) This remedy is known as “tapping” or “sticking.”

Point of puncture for bloat: on the left side … equidistant from the rearmost rib, the edge of the animal’s loin, and the hip bone.

When I come across a calf that’s down and almost dead, I run full speed to the house, grab my paring knife (it’s usually sharp and handy), pour a little alcohol or other antiseptic on it, and dash back to the calf pen to make the “tap. ” (A trocar is nice if you have one, but in a life-or-death situation, a paring knife is better than nothing.) Always remember this: The point of puncture is on the left side equidistant from the rearmost rib, the edge of the animal’s loin, and the hip bone. Put the point of the knife on the puncture site, hold the top of the knife steady with one hand and hit the knife handle with the fist of your other hand. (Keep your face well back when you do this.) I usually leave the knife in place for a few minutes and move it slightly while I work the surrounding area with my free hand to aid the release of gas. After removing the knife, I put antiseptic ointment on the wound.

” (A trocar is nice if you have one, but in a life-or-death situation, a paring knife is better than nothing.) Always remember this: The point of puncture is on the left side equidistant from the rearmost rib, the edge of the animal’s loin, and the hip bone. Put the point of the knife on the puncture site, hold the top of the knife steady with one hand and hit the knife handle with the fist of your other hand. (Keep your face well back when you do this.) I usually leave the knife in place for a few minutes and move it slightly while I work the surrounding area with my free hand to aid the release of gas. After removing the knife, I put antiseptic ointment on the wound.

In the case of a small calf, I usually try to keep the animal’s head elevated (with hay or an old pillow), to avoid having any stomach fluids escape into the lungs. If he seems weak, I’ll then give the calf a shot of Combiotic to ward off infection. I’ve lost count of how many calves I’ve stuck (many of them have belonged to other people), but so far I haven’t lost any animals using this method.

Incidentally, there is such a thing as chronic bloat. Epsom salts and/or mineral oil will relieve the condition, but I don’t know of any permanent cure. (I do know that chronic bloat will slow down a calf’s growth.) — Luilla Thompson

Feeding calves from the first days of life up to six months

Contents:

- What to feed calves in the first month of life?

- What and how to feed for the second and third month?

- What to feed calves up to 6 months?

- What do experts advise?

In order to raise a healthy bull or cow, the newborn calf must be properly cared for and fed. The latter often causes difficulties for breeders. How to feed a young animal before it switches to a normal adult diet? Feeding calves by months from the first days of life is described in detail below in the article.

What to feed calves in the first month of life?

The first 10 days after the birth of a calf, it must be fed with colostrum. Colostrum is the precursor of milk, it appears in the cow immediately after birth. As a rule, it is more than enough to feed the calves from the first days of life, but if not enough, you will have to buy more or take it from another cow.

Colostrum is the precursor of milk, it appears in the cow immediately after birth. As a rule, it is more than enough to feed the calves from the first days of life, but if not enough, you will have to buy more or take it from another cow.

Stages of development of the rumen of the calf

Together with colostrum, the calf receives the necessary trace elements and vitamins that activate its immune system, forcing the body to adapt to the environment, start fighting harmful microorganisms, viruses.

Regardless of the time of birth, the first portion of colostrum is given to the newborn 30 minutes after birth. The norm is 1.5-2.5 liters, depending on the weight of the calf. The first 4 days the calves are fed 6 times a day. From the 10th day, the calf should get used to the 3-fold diet.

A calf should eat 6-8 kg of food per day, that is, approximately 1.5-2 liters of colostrum or milk at a time. For about two weeks, he is fed on colostrum, and then on mother's milk, but then he is transferred to combined milk and whole milk substitutes ("Kormilak"). It is important that the whole milk replacer does not contain vegetable proteins!

It is important that the whole milk replacer does not contain vegetable proteins!

In addition to milk and colostrum in the first month, closer to 4 weeks, you can supplement the calf with boiled potatoes and even start introducing crushed, liquid cereals (oatmeal, semolina). From now on, you can already feed the calf with hay with legume leaves. But in small quantities! On average, the norm in the first month for a calf is 1 kg per day.

In the first month of life, it is important that the calf has full access to water, but only from the 3rd day of life. Lack of moisture in the body can lead to weakness, digestive problems, and so on. Up to 2 weeks give boiled water, and then simple. Instead of water, infusions can also be used, but still there should be a drinker with clean water in the stall.

What and how to feed during the second and third months?

Feeding diet for calves from 1 to 3 months

A month after birth, the animal is considered to be strong, its immune system is fully functional. Therefore, feeding calves with whole milk can be almost completely stopped. The norm of milk per day for 2 months ranges from 3-4 liters per day. This will be enough. Some breeders generally do not give the calf milk for 2 months, but if finances allow, this will not hurt.

Therefore, feeding calves with whole milk can be almost completely stopped. The norm of milk per day for 2 months ranges from 3-4 liters per day. This will be enough. Some breeders generally do not give the calf milk for 2 months, but if finances allow, this will not hurt.

Now the basis of the diet is reverse. They begin to give it in small portions with a gradual increase in the amount. At least 4-6 liters are fed per day. Together with the reverse, plant foods are also introduced. To make it easy for the calf to get used to the new food, you need to purchase easily digestible feed with a lot of nutrients. They are not cheap, but for calves at 2 months old they are perfect!

If it is not possible to buy food, you can prepare it yourself. For this, high-quality leafy hay and oatmeal (sifted) are taken. Separately, hay with small stems, soaked in a salt solution, is poured into the feeders. 800 grams of such food is given per day for 2-3 months.

800 grams of such food is given per day for 2-3 months.

If 2-3 months are in the summer, fresh grass can be given to the young. Up to 2 kg of greens are given per day. From 2 months, vegetables are introduced, only they need to be given gradually, in some animals there may be intolerance to certain products. The norm of hay at this age is up to 1.5 kg per day.

What to feed calves up to 6 months?

Everything you need to feed and keep your calves comfortable

During the 4th month, feeding young calves is no different from feeding a 3-month-old animal. Only concentrates, succulent feed and hay should be given about 1.5 times more.

For the 5th month, the amount of skimming is reduced to 3 liters per day. This month, the calf should consume 1.6 kg of concentrates, 5 kg of fresh greens and 2.3 kg of hay per day.

Active fattening of the animal begins at the age of 6 months. The main part of the diet is feed. The better it is, the less vitamins you will need to buy. During the day, the animal must eat at least 1.6 kg of concentrates, 6.6 kg of fresh grass, 3.3 kg of hay. Returns are no longer given at all.

During the day, the animal must eat at least 1.6 kg of concentrates, 6.6 kg of fresh grass, 3.3 kg of hay. Returns are no longer given at all.

At this time, it is already possible to give young animals the vegetables and fruits they like (apples, carrots, beets, potatoes) in full, as well as adults.

What do experts advise?

In order for the animal to grow quickly, it is worth following some feeding recommendations.

- From 1 to 3 months of age, calves are fed using teat bottles to prevent them from overeating, otherwise obstruction or intestinal upset may develop.

- Any new foods are introduced into the diet carefully, in small portions, so that the body of the calf gradually gets used to them. Otherwise, the appearance of diseases is not excluded.

- As the animal develops, its need for any useful substances increases.

If you do not give the norm for which the body is designed, this can lead to slow growth and development of young animals, insufficient activity, and diseases.

If you do not give the norm for which the body is designed, this can lead to slow growth and development of young animals, insufficient activity, and diseases. - Regardless of age, calves and adults should always have clean, fresh water in the drinker!

- Separately, for enhanced growth of calves, salt, minerals, vitamins, grass flour can be added to the feed.

care and description of possible diseases

After birth, a calf needs special care, regardless of its sex. Only proper maintenance and feeding will ensure the full growth and development of a young animal, which in the future guarantees its successful use for breeding purposes or obtaining high milk yields.

Information from this article tells you in what conditions you need to keep and how to properly feed newborn calves, and photos and videos will help to arrange comfortable conditions for young animals.

Contents:

- How to feed a newborn calf

- Feeding during the milk period (feeding intensity, nutrients)

- Feeding from weaning to puberty

- Completely mixed dry ration for calves

- How to water a newborn calf

- How to care for a newborn calf - video

- In individual cages or houses

- Group cage maintenance

- Tethered calf housing

- How much milk to give to a newborn calf

- Diseases of newborn calves

How to feed a newborn calf

Immediately after birth, the calf should be moved to a cage with a thick layer of straw on the floor. The cage can also be placed in a barn if the room is dry, warm and there are no drafts in it. Otherwise, the cage is transferred to another room. Do-it-yourself drawings for building cages are shown in Figure 1.

The cage can also be placed in a barn if the room is dry, warm and there are no drafts in it. Otherwise, the cage is transferred to another room. Do-it-yourself drawings for building cages are shown in Figure 1.

Feeding newborn calves is a very important stage in their development. In the first days after calving, the cow does not give milk, but colostrum. This is a special substance that contains a huge amount of vitamins, proteins, minerals and antibodies that prevent infectious diseases in young animals. It is colostrum that should form the basis of the diet of animals in the first days of life. It is fed in pairs, first a liter from 4 to 6 times a day, gradually bringing the one-time rate to three liters.

Note: It is important that colostrum changes its composition very quickly, and the amount of useful substances in it is gradually reduced. Therefore, in the first days of birth, young animals should be given the maximum amount of colostrum to ensure rapid growth and develop immunity against infectious diseases and digestive disorders.

In order for the digestion process to normalize faster, calves are given up to one and a half liters of warm water already on the second day after birth. The period of feeding with colostrum lasts no more than five days, after which the cow begins to produce regular milk.

Figure 1. Drawings of cages for keeping young animals: a - an individual cage (1 - a place to rest, 2 - a hay feeder, 3 - a feeder for concentrates), b - a portable cage (1 - a feeder, 2 - a slatted floor, 3 - slurry film, 4 - slurry container)Calf management also plays an extremely important role. In order for the animal to grow up healthy, it is necessary to adhere to the following rules:

- Twice a day, clean the cage of manure, thoroughly wash the contaminated places and change the bedding;

- Dishes for feeding and drinking, as well as for milking colostrum, after each feeding must be thoroughly washed and scalded with boiling water;

- In the early days, you need to make sure that the animal drank colostrum in small sips, so for this purpose it is better to use a drinker with a nipple;

- If there is no special nipple, the individual is fed from an ordinary pail, moistening a finger in colostrum to show him where the food is;

- When the animal learns to drink on its own, the bucket can be attached to the wall of the cage and colostrum can be poured into it from the outside.

It is better to keep newborn calves in special cages with a plank floor with slots for urine drainage. A drinking bowl for milk and a feeder are installed in front of the cage. In this cage, the animal is up to three months of age. Instead of a portable cage, you can arrange a fence next to the cow and place a thick layer of straw bedding in it. Cleaning and feeding requirements remain the same as when kept in a portable cage. Examples of cells for are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Types of cages for keeping calvesFeeding during the milk period (feeding intensity, nutrients)

Feeding newborn calves in the first few days after calving involves feeding the animal with colostrum. It is better to keep the animal in a separate cage, and not together with the cow, since when being next to the female, the calf will drink plenty, which in the future may negatively affect the cow's milk production (Figure 3).

Note: Colostrum is an essential food for newborns. It includes not only all the necessary nutrients, but also vitamins and minerals that increase immunity.

Feeding newborn calves is best done with a special teat. So you can control the amount and intensity of food intake. If he drinks too greedily, the colostrum in his stomach will curdle, and this can cause indigestion. You can not postpone the time of the first feeding. Regardless of the time of day when the calving has passed, the first milking and the issuance of colostrum are carried out no later than 30 minutes after calving. If this is not done, the animal will develop a sucking reflex, and if the young animal does not receive colostrum, it will begin to lick the walls and bedding.

Figure 3. Ways of feeding young animals with milk Feeding of newborn calves from three weeks of age becomes more varied. Up to this point, only colostrum and milk should be included in their diet.

Later the ration is gradually replenished :

- Boiled potatoes are used as top dressing;

- Milk is still included in the diet, but its amount is being gradually reduced. Instead of cow's milk, special substitutes can be given;

- From the age of one month, the body is considered sufficiently strong, and milk can be replaced with skim milk. Start with a small amount of the product, gradually increasing its share in the diet;

- High-quality hay can be filled into the feeders. It should be small so that the animals gradually learn to chew. Hay is best moistened with saline to prevent worms.

From the age of two months, concentrates are introduced into the diet. For these purposes, mixes of cereals, bran and oilcake are used. Gradually, green grass is introduced into the diet if a newborn calf was born in the summer.

Feeding after weaning until puberty

We found out how to feed a newborn calf, it remains to determine what is better to feed the animals in the future. The composition of the diet depends on the sex of the animal, since heifers and bulls are used for different purposes and require certain nutrition.

The composition of the diet depends on the sex of the animal, since heifers and bulls are used for different purposes and require certain nutrition.

Females are kept for breeding purposes or for raising high producing dairy cows. For breeding purposes, it is necessary to select healthy, large individuals, with normal development and without defects. Good milk yields can only be obtained from animals with a good origin (from a high-milk cow and a thoroughbred productive bull).

Feeding heifers is extremely important, so the animal's diet must be balanced :

- Lack of protein provokes growth retardation, and its excess provokes a decrease in the use of this nutrient;

- The individual must receive sufficient amounts of calcium and phosphorus necessary for bone growth and tissue development;

- The diet should also include iron, cobalt, iodine and table salt;

- Vitamins A and D are of great importance in development (obtained from fishmeal, high-quality hay and irradiated yeast).

In addition, for the synthesis of vitamin D, animals need to be regularly walked in the fresh air;

In addition, for the synthesis of vitamin D, animals need to be regularly walked in the fresh air; - The diet should consist of various types of feed: whole milk, concentrates, succulent feed (silage and root crops), hay and mineral supplements.

On the first day after birth, the female is fed only colostrum, the volume of which depends on the planned growth rate. They are accustomed to the skimmed milk gradually, and it can only be given to individuals of one month of age. Traditionally, they are fed milk for only 10-20 days, after which they are transferred to other feeds. However, to ensure normal growth, it is better to extend this period to three to four months.

Figure 4. Food for females: 1 - dry oatmeal, 2 - hay, 3 - milk or skim, 4 - lick saltTo ensure the rapid growth of the animal, feed should be dosed and prepared correctly (Figure 4).

- Dry oatmeal - start feeding from 15-20 days of age.

Before serving, oatmeal is sieved through a sieve, mixed with warm water and poured into a feeder (you can also feed it through a bottle).

Before serving, oatmeal is sieved through a sieve, mixed with warm water and poured into a feeder (you can also feed it through a bottle). - Salt, chalk is introduced into the diet from the 11th day of life. The initial rate is 5 grams, but as the animal grows, the amount of salt given out increases.

- Hay starts to be given out on the 10-15th day. You can lay it out in the feeder or hang it around the cage in the form of brooms. Only high quality hay is suitable for feeding.

- Succulent feed (potatoes, root crops and quality silage). Feeding begins from the second month after birth. Juicy feed is prepared separately. As a basis for silage, it is desirable to use a mixture of young clover or alfalfa with cereals, supplementing them with legumes and boiled potatoes.

Milk, skim milk, succulent feed and concentrates are dispensed in doses according to the age of the animal. Silage and hay can be fed in unlimited quantities.

Oatmeal from the second month of life is replaced by corn or a mixture of concentrates. The lack of silage can be made up for by a large dose of root crops.

After the start of grazing, the diet should be reviewed, making the following adjustments to it:

- Up to 3-4 months of life, the amount of milk and concentrated feed is left at the same level;

- Eliminate hay and silage from the diet, replacing it with green grass;

- If pasture grass quality is poor, animals should be supplemented with mowed green plants;

- From the age of 3-4 months, in the presence of a sufficient amount of green fodder, half of the root crops and concentrates are excluded from the diet.

The first three months of heifers are kept in special portable cages, the design of which does not allow the animal to turn around. This prevents contamination of feeders and drinkers with faeces and urine. They can also be kept on bindings next to the mother, equipping a feeder and drinker.

See also: Feeding cows at home

In the first 15-20 days of life, the animal should be walked daily for 15-20 minutes, gradually increasing the time of walking. In the summer, they can be kept outdoors almost all day (grazing on a leash). Young females are not recommended to be driven out to a common pasture due to the high risk of infection with worms.

The stall and cage should be cleaned regularly, the bedding changed and whitewashed regularly.

Heifers older than six months are given mainly hay and silage in winter, and green grass in summer. The diet should also include succulent feed and concentrates. One-year-olds can be given spring straw, but it must be supplemented with other feeds. Root crops in their entirety can only be given to animals over a year old, and young animals must be crushed without fail.

Young bulls for slaughter are best fattened to 15-20 months of age, with a heavy feed for the last three months. In this case, by the time of slaughter, the live weight of the bull will exceed 400 kg.

In this case, by the time of slaughter, the live weight of the bull will exceed 400 kg.

Note: Quite often, the lack of feed in home gardens forces owners to slaughter bulls earlier. This is not recommended, especially for individuals born in the spring, since the abundance of inexpensive feed in the summer allows you to quickly grow a bull of the desired weight.

Young bulls up to six months are fed with milk, supplementing the diet with other types of feed. This ensures the fastest possible growth of the young. Animals born in the spring can be given green grass instead of coarse and succulent feed, and to save concentrates, it is advisable to graze bulls on a leash. You can see examples of feed for fattening bulls in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Feed for bulls: 1 - milk, 2 - silage, 3 - green grass, 4 - concentrates of industrial production About half of the diet of a one-year-old bull intended for slaughter should be silage. In the future, its percentage increases, and coarse and succulent feeds are given out in smaller quantities. In summer, young bulls (from 12 to 18 months old) can be kept exclusively on pasture, without giving concentrates to animals.

In summer, young bulls (from 12 to 18 months old) can be kept exclusively on pasture, without giving concentrates to animals.

Bull calves are less picky eaters in the early fattening phase, so they can be fed roughage or offal. But as the animal grows, and especially at the end of fattening, more and more juicy and concentrated feeds are included in the diet.

Immediately before slaughter, part of the silage is replaced with concentrates. It is advisable to keep young bulls in a corral, arranging daily walks for them to increase their appetite.

Dry Full Mixed Calf Diet

Recent studies have shown that the use of Dry Full Mixed Calf Diet produces healthy and strong calves. The essence of this feeding is that a newborn animal eats high-quality hay and grain concentrates, which provoke the development of a scar.

How to feed newborn calves on a dry full mixed ration? To do this, you need to prepare the necessary feed and properly prepare them (Figure 6):

- Hay is taken only short and high quality.

If the hay is long, the animals will not eat it. You can replace hay with high-quality chopped straw;

If the hay is long, the animals will not eat it. You can replace hay with high-quality chopped straw; - Young stock feed is used to balance hay or straw. The share of hay is approximately 80%, the rest should be occupied by compound feed;

- Hay and compound feed are mixed and supplemented with mineral supplements.

dry full-blend calf ration A full-blend dry mix can be supplemented with linseed meal or cake and a small amount of grain. It is possible to introduce such a feed mixture from the second week of life, starting with small doses and gradually increasing the amount of feed.

How to give water to a newborn calf

Almost immediately after birth, a calf should be given warm colostrum to drink. In the first few days, it is drunk 4-6 times a day. Knowing how much a newborn individual weighs, you can determine how much colostrum he needs to be given at a time. On average, this volume is 0.5-1 liter. In the future, the one-time rate is increased to 2-3 liters.

Note: The intake of colostrum during the first few days plays a very important role in the development of the animal. It is thanks to colostrum that it grows rapidly, gains weight and receives the antibodies necessary to resist diseases.Figure 7. Watering of a newborn calf

It is important not only to give the calf the correct amount of colostrum, but also to ensure that he drinks correctly (Figure 7). First, nipples are used for this, and after a week they are transferred to special drinkers or buckets. Warm milk or colostrum is poured into the container, a finger is moistened in it and the animal is allowed to drink. When the animal gets used to drinking from a bucket, the container is simply hung on the wall of the cage.

How to care for a newborn calf - video

A newborn calf needs careful care, as its body is not yet strong enough. Animals are especially sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity. Therefore, immediately after birth, he is transferred to a separate stall with clean bedding. The room should be heated, and in winter it should be equipped with artificial lighting.

The room should be heated, and in winter it should be equipped with artificial lighting.

In individual cages or huts

Individual housing of calves in special cages or huts is considered a relatively new method. Immediately after birth, the animals are transferred to special houses without insulation, but with bedding. A small paddock is arranged near the house (Figure 8).

Keeping calves in individual houses makes it easier to care for them, strengthens the immunity of animals and prevents the spread of diseases.

Figure 8. Individual houses for young animalsIt is this method that is widely used abroad, but for our country it turned out to be unsuitable in several respects:

- reverse effect. Calves not only did not improve their health, but on the contrary, the number of individuals infected with bronchitis or pneumonia increased.

- The arrangement of individual houses requires an investment of money, which is not available to many households.

Wooden houses are often used instead of plastic ones, but they must be placed under a canopy, as during rain the wood picks up moisture and becomes too cold.

Group cage keeping

Care of newborn calves, in which all young animals are kept in cages in groups of 10-15 individuals, is more traditional for our country. With this method of keeping, the newborn animal is in a small individual stall for the first two weeks (sometimes in the same room where the cow is kept), and after this period it is transferred to a large cage and kept with individuals of the same age (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Group housing On large farms, a separate room is equipped for this purpose. Inside, it is divided into compartments for keeping in small groups. The group is formed by age, as this facilitates the process of care and the formation of a diet. The main disadvantage of this method is considered to be large labor costs, since the attendants need to spend a lot of time and effort on cleaning the cages and dispensing feed.

Tethered keeping of calves

Tethered keeping is practiced mainly for older animals. Newborn calves are also kept in separate stalls, but their size allows the calf to move freely and there is simply no need for a leash.

See also: How to build a barn with your own hands

Tethered housing is used in home gardens in winter, when the calf is indoors most of the day, and goes out for a walk for only a few hours. When tethered, the stall is made in such a way that the calf feels relatively free, but at the same time it cannot turn its back to the feeder and drinker. The harness should be long enough so that the calf can lie down at any time.

A feeder and drinker are installed inside the stall, and a slurry chute is installed in the back of the stall. The floor in the stall is done at a slight slope.

How much milk to give to a newborn calf

Immediately after birth, the milk consumption rate is 0.5-1 liter. But this figure depends on the weight and individual characteristics of the animal. At the first feeding, it is recommended to pour more milk into the nipple so that the animal can drink freely.

But this figure depends on the weight and individual characteristics of the animal. At the first feeding, it is recommended to pour more milk into the nipple so that the animal can drink freely.

In the future, before switching to feeding with hay and green grass, one individual drinks 2-3 liters of milk. It must be warm, and special nipples or buckets are used for drinking. Drinking containers should be kept clean and disinfected regularly.

Diseases of newborn calves

Young cattle are susceptible to various diseases, as their bodies are not strong enough to withstand environmental factors.

See also: Diseases of cows and their symptoms

The most common diseases of newborn calves include (Figure 10): This disease can occur when hygiene rules are not followed or because the navel is cut with too sharp scissors. If the umbilical cord has become edematous, you need to bandage it, and if pus begins to stand out from the wound, call the veterinarian to prescribe special treatment.