Pump feeding baby

How to breastfeed without nursing

During my three-month maternity leave, I struggled to develop a successful nursing relationship with my son. Breastfeeding felt like the obvious choice, but before we even left the hospital, we were forced to supplement with formula when my son kept losing weight. After a difficult labour and an unplanned C-section, I felt like my body was failing me in the last way possible, depriving me of the ability to nourish my son.

I felt guilty about giving my son formula, knowing that my body produced the perfect food for my baby. I was determined to make it work. Over the next few weeks, while I was suffering from toe-curling nipple pain, swollen breasts and exhausting feeding and pumping sessions to boost my supply, my son was also having trouble taking in enough milk at the breast.

His latch was fine and he had no visible tongue or lip tie, but at five weeks, one of the specialists I saw finally diagnosed the problem: oral motor difficulties—more specifically, weak jaw, tongue and cheek muscles. Try as he might, my son’s little muscles weren’t strong enough to nurse efficiently, which explained my engorgement and his frustration. For three weeks, I did the recommended at-home exercises to strengthen his muscles while continuing to supplement with formula as needed. On the advice of one of the certified lactation consultants, I tried to pump after every feeding to stimulate milk production. Between feeding and pumping, my days were consumed.

Despite everything I was doing to make breastfeeding work, my supply suffered, along with my will to keep fighting. Nearly every time my son nursed, he inevitably cried for a bottle of formula afterwards. I knew some of his issues were improving when the pain subsided, but I couldn’t keep up with his demand for milk.

One night, I finally admitted defeat. Direct nursing seemed too fraught with anxiety to continue—I would just pump and bottle feed. Pumping allowed me to hang onto the last shred of breastfeeding I had left. I stubbornly clung to this idea as I cursed a system where it took weeks to get the help I needed to correct my feeding issues. Although I felt relieved to take the guesswork out of feedings, I also felt like a complete failure for not being able to nurse my baby directly.

I stubbornly clung to this idea as I cursed a system where it took weeks to get the help I needed to correct my feeding issues. Although I felt relieved to take the guesswork out of feedings, I also felt like a complete failure for not being able to nurse my baby directly.

Meanwhile, my entire schedule revolved around my next pump. I also faced people who questioned my choice, admonishing me for “taking the easy way out” or telling me that formula would make my life easier. For nine long months, until a noticeable supply dip prompted me to wean, I pumped five or more times a day to provide my son with roughly 18 ounces of breastmilk and kept supplementing with formula. I stopped feeling guilty about the top-ups with formula—it was a crutch that took the pressure off my output goals—and started thinking of it as the “protein shake” of my son’s diet, not a replacement for the main source of his nutrition.

In doing so, I didn’t realize that I had joined the ranks of thousands of other women just like me who had chosen, for various reasons, to pump exclusively instead of breastfeed. Moms who pump exclusively often fly under the radar in cultures that view feeding as a dichotomy—my own doctor’s office still asks whether moms breastfeed or bottle feed (that is, formula feed). There’s little understanding of the hard work and dedication to find something that works in between those two choices.

Moms who pump exclusively often fly under the radar in cultures that view feeding as a dichotomy—my own doctor’s office still asks whether moms breastfeed or bottle feed (that is, formula feed). There’s little understanding of the hard work and dedication to find something that works in between those two choices.

“Mothers who pump exclusively may or may not actually initiate this based on their personal choice,” says Jenn Foster, an international board-certified lactation consultant (IBCLC) based in Georgia. She says that mothers of preterm babies often pump exclusively after working to supply breastmilk to their babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Historically, mothers of preterm and low-birth-weight babies comprised the bulk of mothers who pump exclusively. Now, the improved quality and availability of electric pumps make the option more viable for other groups of women.

Mothers of full-term babies often choose to pump exclusively when they struggle with latching or supply issues and when they don’t receive enough support in the early days of breastfeeding—both of which happened to me.![]() Some moms choose to pump because it’s the best decision for their families, while others simply prefer to monitor their milk intake—which you can’t really do when you’re nursing directly. There are also women who have very limited maternity leaves, so they start pumping and bottle feeding rather than spending precious time perfecting their babies’ latches. Abuse survivors may choose to pump if the demands of nursing their babies trigger adverse physical or emotional reactions that they are unable to work through. In such cases, pumping instead of nursing directly may help them dissociate the breastfeeding experience from past abuses.

Some moms choose to pump because it’s the best decision for their families, while others simply prefer to monitor their milk intake—which you can’t really do when you’re nursing directly. There are also women who have very limited maternity leaves, so they start pumping and bottle feeding rather than spending precious time perfecting their babies’ latches. Abuse survivors may choose to pump if the demands of nursing their babies trigger adverse physical or emotional reactions that they are unable to work through. In such cases, pumping instead of nursing directly may help them dissociate the breastfeeding experience from past abuses.

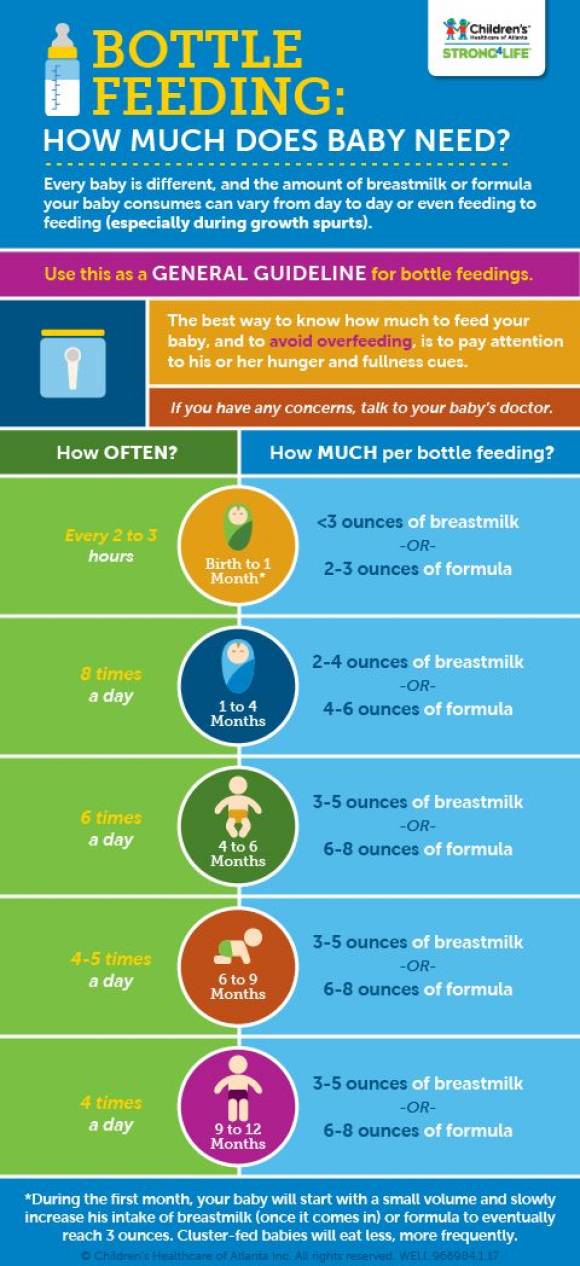

Newborn babies nurse eight to 12 times a day on average, so a mother who pumps exclusively should pump that often to keep up with the demand for milk. Foster encourages mothers to pump every two or three hours. “It is not recommended to go longer than three hours at a time without expressing your milk,” she cautions. During the first month of a baby’s life, too much variation from this around-the-clock regimen signals the body to reduce milk production, says Foster. I believe that deviating from this schedule throughout my early struggles contributed to my supply issues.

During the first month of a baby’s life, too much variation from this around-the-clock regimen signals the body to reduce milk production, says Foster. I believe that deviating from this schedule throughout my early struggles contributed to my supply issues.

As with direct nursing, pumping sessions should be timed from the beginning of one session to the beginning of the next. Most general guidelines suggest 15 minutes per session, but the exact amount of time varies based on individual responses to the pump. Foster stresses the importance of draining the breasts. “Milk needs to be removed to be made,” says Foster. Pumping several minutes past when milk stops flowing will ensure that a woman removes enough milk to maintain her current average output and avoid clogged ducts and mastitis.

While the number of daily pumping sessions should correspond to the frequency of a baby’s feeds, moms who pump exclusively can follow whatever schedule works for them as long as they follow it like clockwork while establishing their supply. After establishing their supply, they can continue to adjust their routine. There are various pump logging apps that allow women to monitor the time, duration and yield of each pump. Depending on the app, additional features may include monitoring totals, averages and trends and calculating when to wean based on freezer stashes.

After establishing their supply, they can continue to adjust their routine. There are various pump logging apps that allow women to monitor the time, duration and yield of each pump. Depending on the app, additional features may include monitoring totals, averages and trends and calculating when to wean based on freezer stashes.

Not all pumps are created equal, and what works for occasional use may not endure the rigours of pumping exclusively. Foster recommends that women who pump exclusively look for a quality, closed-valve, hospital-strength pump. Any pump rated 250 mmHG or higher is hospital strength. Pumps with customization settings for vacuum pressure and speed can be adjusted to individual needs.

Closed-valve systems prevent milk from passing through tubing to the motor, making them the most sanitary choice. They are especially important for women who are considering rentals or used pumps, as the inner motors of most pumps can’t be completely sanitized. Women who rent or buy used pumps should also consider the motors because they may not be designed for multiple users. To be rental-quality, a pump should be labelled as “multi-user.” Milk collection kits (tubing, breast shields and collection bottles) can’t be thoroughly sterilized at home and should always be purchased new.

Women who rent or buy used pumps should also consider the motors because they may not be designed for multiple users. To be rental-quality, a pump should be labelled as “multi-user.” Milk collection kits (tubing, breast shields and collection bottles) can’t be thoroughly sterilized at home and should always be purchased new.

Foster also recommends using a double pump. “Double pumping allows for your hormonal peaks to occur more frequently during your pumping experience,” says Foster. The hormones that Foster refers to—prolactin and oxytocin—signal the body to produce and release milk.

Multi-user rental pumps are usually available from hospitals, medical supply centres and authorized lactation consultants. Spectra, Philips Avent and Lansinoh make closed-valve, single-user pumps that range from $150 to $300 or more. These single-user pumps may be covered by some insurance plans.

How to maintain your milk supplySince moms who pump exclusively measure the amount of milk expressed, output volume can easily become a source of stress. Some new mothers panic when their initial output is as little as two ounces combined per session, but Foster stresses that this is normal. If all goes well, women can expect an average daily output of anywhere from 19 to 30 ounces. Moms who struggle to make sense of their output should work with lactation consultants to determine best practices and receive personalized guidelines.

Some new mothers panic when their initial output is as little as two ounces combined per session, but Foster stresses that this is normal. If all goes well, women can expect an average daily output of anywhere from 19 to 30 ounces. Moms who struggle to make sense of their output should work with lactation consultants to determine best practices and receive personalized guidelines.

Foster says that a woman’s supply naturally starts to self-regulate and the milk composition changes (often to a higher fat content) around the four- to six-month mark. A similar shift occurs around the eight- to 12-month mark. If a mom has kept pace with her baby’s feeding schedule, she should find that her supply continues to meet her baby’s needs. She can take further steps to ensure that her baby’s appetite doesn’t exceed her supply by using slow-flow nipples, practising a variety of paced feeding techniques and stretching bottle-feeding sessions to closely mimic breastfeeding.

Other common culprits for supply fluctuations are worn, damaged and incorrect parts. Moms should inspect and replace the parts, especially valves and membranes, regularly. When used frequently, these parts should be replaced every one to two months or at the first sign of wear and tear. Moms should consult an IBCLC to help select the correct breast shield, or flange size, and eliminate issues that stem from incorrect pumping techniques.

Moms should inspect and replace the parts, especially valves and membranes, regularly. When used frequently, these parts should be replaced every one to two months or at the first sign of wear and tear. Moms should consult an IBCLC to help select the correct breast shield, or flange size, and eliminate issues that stem from incorrect pumping techniques.

Concerned moms may seek galactagogues (dietary and herbal remedies), which are thought to increase milk supply. Common over-the-counter galactagogues include fenugreek, moringa, blessed thistle and some herbal teas. In some countries, including Canada, health providers may prescribe domperidone (a pill used for gastric issues that has proven to be effective at boosting milk supply). Foster recommends consulting your primary caregiver before starting any dietary regimen or supplement. She cautions that some products may react with other medications and medical conditions. “A full medical history is needed to assess [each] mother and baby,” says Foster.

According to Foster, moms who pump exclusively are often ostracized from support groups that are geared toward solely breastfeeding or formula feeding. “These mothers often deal with feelings of inadequacy, which should not be the case,” says Foster. “[Pumping] is actually a great dedication of love.”

Fortunately, support groups for moms who pump exclusively do exist. I connected daily with moms in the Facebook group I joined. They welcomed me into their ranks, offering advice and encouragement when I needed it most. Throughout my journey, they taught me that moms who pump exclusively haven’t failed; they’ve simply chosen an alternate route that takes as much—if not more—hard work and dedication as direct nursing. Now, when I look at my happy, thriving 18-month-old, I marvel at the lengths I went to breastfeed him and how far our journey has taken us.

Stay in touch

Subscribe to Today's Parent's daily newsletter for our best parenting news, tips, essays and recipes.

- Email*

- CAPTCHA

- Consent*

Yes, I would like to receive Today's Parent's newsletter. I understand I can unsubscribe at any time.**

FILED UNDER: Breast milk Breast pumps breastfeed Newborn

What You Should Know About Exclusive Pumping

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

In this Article

- Why Would You Pump Exclusively?

- How to Pump Breast Milk

- What Are the Pros and Cons of Exclusive Pumping?

Exclusive pumping is when you feed your baby only pumped milk, as opposed to direct breastfeeding.

In practice, you express (i.e., squeeze out) milk from your breast using a pump and then put the milk inside a bottle. You then feed your baby using the bottle or a nasogastric tube if they are premature. Just as you would when breastfeeding, you observe a pumping routine every time your child needs to feed, or you can express a lot of milk and store it in the fridge to warm when the baby needs it.

In most cases, exclusive pumping is done when the baby is not getting enough milk as they would when they are being breastfed (nursed) normally. This may happen if you are not producing enough milk or if your baby is not breastfeeding the right way.

Why Would You Pump Exclusively?

Exclusive breastfeeding is not for everyone. Although it is recommended that you feed your baby directly from the breast for the first six months, sometimes it may not be possible. As a result, you are left with no choice but to pump and feed your baby breast milk from a bottle. The most common reason for exclusive pumping is when your baby is not latching as they should. Latching is how the baby fastens onto the breast while nursing. Your lactation expert may advise you to pump every few hours or as your schedule allows.

When distance separates you and your baby. In some cases, a situation may arise that puts you away from your baby for a long time. For instance, the U.S. federal law provides up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for the birth of a baby. You may be required to be back at work before it is time to wean your baby (i.e., make your baby used to food other than breast milk). If you are in such a position, pumping and leaving your baby’s caretaker with the pumped milk is almost inevitable. Pumping allows you to feed your baby on breast milk even when you are away.

For instance, the U.S. federal law provides up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for the birth of a baby. You may be required to be back at work before it is time to wean your baby (i.e., make your baby used to food other than breast milk). If you are in such a position, pumping and leaving your baby’s caretaker with the pumped milk is almost inevitable. Pumping allows you to feed your baby on breast milk even when you are away.

When you have tried your best to breastfeed and it does not work, pumping is the best option to feed your baby with breast milk. However, there are other reasons why you may find yourself adopting the practice. They include the following:

- Child adoption

- Congenital condition

- Breast anomalies

- Weight loss strategy

- Infant illness

- Oral anomalies

- Maternal choice

How to Pump Breast Milk

Pumping might feel strange if you have never done it before. You can always ask for suggestions from experienced mothers to help you. To do it best, start by finding a comfortable place with no distractions. It is important to be relaxed when collecting milk. Some mothers prefer looking at pictures of their children or listening to relaxing music.

To do it best, start by finding a comfortable place with no distractions. It is important to be relaxed when collecting milk. Some mothers prefer looking at pictures of their children or listening to relaxing music.

Others get better results when they do hand expressing for 1 or 2 minutes before using the pump. The touch of your hand gives stimulation that helps to produce enough milk. Remember to stay hydrated by drinking plenty of water or alternative fluids.

Choosing a breast pump. Different breast pumps are good in different situations. To pump well, match your and your baby’s needs to a pumping system that meets them. You can consider the pump’s efficiency, ease of movement, and how much noise it makes.

You may find that a hand-operated pump works best for you if you only need to express occasionally. They are usually small, cheap, and easy to carry. If you will be pumping more often, go for an electric or double electric pump. These are recommended if the time you have to pump is limited and you will be pumping three or more times a day.

Electric pumps are automatic and quiet, and they usually mimic or imitate the suck-release pattern of a baby while breastfeeding. A double electric pump can be large, and it comes with a carrying case that resembles a handbag.

Another type of pump is the hospital-grade pump. This pump is only used in a hospital setting when you are separated from a prematurely born baby. Another instance when this type of pump can be used is when you need strong stimulation to produce enough milk. Since you cannot buy one of these, you can locate a hospital that rents theirs out if you are in need.

What Are the Pros and Cons of Exclusive Pumping?

Pros. Exclusive pumping has certain advantages, including the following:

- Bonding: Breastfeeding requires privacy and can draw your attention away from other family members. Pumping allows your baby to feed without taking you away from your family.

- Someone else can help: Unlike breastfeeding where only the mother is involved, pumping allows you to give charge of feeding to someone else while you rest or do other things.

- Uninterrupted work: With exclusive pumping, you can work a demanding job and still manage to feed your baby on breast milk.

- Protect your milk supply: If you are unable to nurse for a period of time, pumping helps to keep your milk levels in check.

Cons. There are also some disadvantages of exclusive pumping, including the following:

- Expensive: Most good pumps are a bit pricey. When you consider other costs, like getting bottles and sanitizing products, breastfeeding directly is way cheaper.

- A lot of extra cleaning: The extra tools used for pumping need regular cleaning to make sure that you and your baby are protected from germs.

- Time-consuming: As opposed to picking your baby and holding them your breast to nurse (feed), pumping involves additional tasks, like thawing frozen milk you stored in the freezer.

- Lifestyle change: Because it is recommended that you pump at least once every night to ensure a good milk supply, waking up every night can change your sleep patterns.

Also, you may find it boring to wake up every night to pump all by yourself.

Also, you may find it boring to wake up every night to pump all by yourself.

When you begin to exclusively pump, it is normal to feel overwhelmed. Seek professional information and create a schedule that works for you and your baby.

If you need to use lubrication, consider olive oil and lanolin. Utilizing a lubricant helps you to avoid nipple damage and to reduce friction.

Bolus Feeding Using a Syringe)

Your child is discharged from the hospital with a nasogastric (NG) feeding tube in place. The tube is a thin, soft tube that is inserted into the baby's stomach through the nose. This tube delivers liquid food directly to the stomach. Before your baby was released from the hospital, you were shown how to feed with a nasogastric tube. This memo will help you remember the necessary procedure for feeding at home. You can also get help from a district nurse at your home.

NOTE: There are many different types of nasogastric tubes, feeding syringes, and pumps. The appearance and function of the nasogastric tube and accessories prescribed for your child may differ from those shown and described below. Always follow the advice of your child's primary care physician or district nurse. Write down their phone numbers in case you need help. Also write down the phone number of the facility that supplies medical equipment for your child. In the future, you will need to order additional accessories that your child may need. Write down all the phone numbers you need in the spaces below.

The appearance and function of the nasogastric tube and accessories prescribed for your child may differ from those shown and described below. Always follow the advice of your child's primary care physician or district nurse. Write down their phone numbers in case you need help. Also write down the phone number of the facility that supplies medical equipment for your child. In the future, you will need to order additional accessories that your child may need. Write down all the phone numbers you need in the spaces below.

Healthcare provider phone number: _________________________________________________________

Home health nurse phone number: _________________________________________________

Medical supply company phone number: ______________________

Types of feeding

-

Two types of feeding can be performed with a nasogastric tube:

-

bolus feeding.

Several times a day, an amount of liquid food, commensurate with one meal, is fed through the tube. Bolus feeding is done with a syringe or pump;

Several times a day, an amount of liquid food, commensurate with one meal, is fed through the tube. Bolus feeding is done with a syringe or pump; -

continuous feeding. Liquid food drips slowly through the probe. Continuous power is supplied by a pump.

-

-

Your child may be prescribed one or both types of food. Detailed instructions for each type of food are given below.

Syringe Bolus

Your child's doctor or district nurse will tell you how much liquid food to use with each bolus. You will also be told how many times a day to feed your baby. Record this information below.

How much to give at each feeding: _____________

Number of feedings per day (How often to feed): __________________________

Accessories

Actions

-

Wash your hands with soap and water.

-

Make sure the tube is in the stomach (as you were shown in the hospital). Be sure to perform this step BEFORE feeding begins.

-

Check liquid food label and expiration date. Never use jars (or bags) with food that have already expired. In this case, you must use a new jar (or bag) with food.

-

Open the hole plug at the end of the food probe.

-

Remove the plunger of the feeding syringe.

-

Connect the feeding syringe to the feeding port of the probe.

-

Gently bend or squeeze the probe with one hand. While holding the tube bent or pinched, slowly draw the liquid food into the feeding syringe with your free hand.

In this case, the food will not flow through the probe, which will allow you to measure its amount.

In this case, the food will not flow through the probe, which will allow you to measure its amount. -

Fill the feeding syringe to the level prescribed by the child's healthcare provider.

-

The probe can now be released.

-

Hold the feeding syringe straight. In this case, the food will pass through the probe by gravity without additional pressure. Adjust the angle of the feeding syringe to control the rate of fluid flow.

-

If the food flows too slowly or does not flow at all, insert the plunger into the syringe. Gently, lightly press the piston. This will remove any particles blocking or clogging the probe. Do not push the syringe plunger all the way or with force.

-

Refill the feeding syringe with food if necessary.

Repeat the above steps until the child receives the prescribed amount of food.

Repeat the above steps until the child receives the prescribed amount of food. -

After feeding, rinse the tube with water (as you were shown in the hospital).

-

Disconnect the feeding syringe.

-

Close the cap on the food inlet of the probe.

| AddiAdditional instructions:_________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Call your doctor right away if you experience any of the following.

-

The child has trouble breathing.

-

Formation of redness, swelling (swelling), leakage (leakage), ulcers (sores) or suppuration (pus) on the skin in the area of the probe.

-

Presence of blood (blood) around the probe, in the child's stool or stomach contents.

-

Baby coughing (cough), shortness of breath (choke) or vomiting (vomit) while feeding.

-

Urebenka swollen (bloated abdomen) or hard abdomen (rigid abdomen) (abdomen hard with light pressure).

-

Child diarrhea (diarrhea) or constipation (constipation).

-

Child temperature (fever) 38˚C ( 100.4° F) or higher.

© 2000-2022 The StayWell Company, LLC. All rights reserved. This information is not intended as a substitute for professional medical care. Always follow your healthcare professional's instructions.

All rights reserved. This information is not intended as a substitute for professional medical care. Always follow your healthcare professional's instructions.

Was this helpful?

Yes no

Tell us more.

Check all that apply.

Wrong topic—not what I was looking for.

It was hard to understand.

It didn't answer any of my questions.

I still don't know what to do next.

other.

NEXT ▶

Last question: How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?

Not at all A little Somewhat Quite a bit Extremely

Enteral nutrition (tube feeding)

What is enteral nutrition?

Sometimes during treatment and recovery, children with cancer cannot get the calories and nutrients they need orally. Tube feeding, or enteral nutrition, provides nutrition in the form of a liquid or mixture given through a tube that is inserted into the stomach or intestines. Some medications may also be delivered through such a tube (probe).

Tube feeding, or enteral nutrition, provides nutrition in the form of a liquid or mixture given through a tube that is inserted into the stomach or intestines. Some medications may also be delivered through such a tube (probe).

Typically, the tube is inserted in two ways:

- Nasal (non-surgical)

- Through a small incision in the abdomen (surgical method)

Most commonly used are nasogastric tubes and gastrostomy tubes. But there are several types of enteral feeding tubes that differ in the method of insertion and location in the digestive tract.

Sometimes the patient is simply not able to eat enough calories or protein. There is no fault in this. It is important to help your child understand that nutritional support is not a punishment. Most children get used to the enteral feeding tube quickly. It is important that the child does not touch or pull the phone. Follow skin care instructions at the insertion site to avoid irritation or infection.

A nasogastric tube is inserted into the stomach or small intestine through the nose and throat.

Enteral feeding tube types

Enteral feeding tube connects to the stomach or small intestine. The location depends on how the patient tolerates the formula and how well their body is able to digest the nutrients. If possible, they try to place the probe in the stomach so that digestion occurs naturally.

There are 5 types of enteral feeding tubes:

Nasogastric Tube . A nasogastric tube is inserted into the stomach through the nose. It passes through the throat, esophagus and into the stomach.

Nasojejunal Probe . A nasojejunal tube is similar to a nasogastric tube but passes through the entire stomach into the small intestine.

Gastrostomy Tube (Gastrostomy Probe) . A gastrostomy tube is inserted through a small incision in the skin. The probe in this case passes through the wall of the abdominal cavity directly into the stomach.

Gastrojejunostomy tube (gastrojejunostomy probe) . The gastrojejunostomy tube is inserted into the stomach like a gastrostomy tube, but passes through the stomach into the small intestine.

Jejunostomy Probe . A jejunostomy tube is inserted through a small incision in the skin and passed through the abdominal wall into the small intestine.

Nasal tubes, including nasogastric and nasojejunal tubes, are generally used for short-term enteral feeding, usually not more than 6 weeks. The probe comes out of the nostril and is attached to the skin with adhesive tape. Nasogastric and nasojejunal tubes have a number of advantages, such as a low risk of infection and a simple insertion procedure. However, the probe must be attached to the face, and this worries some children. Other children may have problems with the nasogastric tube due to chemotherapy, which irritates the skin and mucous membranes.

Surgical insertion tubes - gastrostomy tube, gastrojejunostomy tube and jejunostomy tube - are used for longer periods of time or if a nasal tube cannot be placed in the child. The opening in the abdominal wall through which the probe is inserted is called the stoma. A long tube or a "button" (low profile) probe may be visible on the patient's body. After healing, the stoma is usually pain free and the child can perform most daily activities.

The opening in the abdominal wall through which the probe is inserted is called the stoma. A long tube or a "button" (low profile) probe may be visible on the patient's body. After healing, the stoma is usually pain free and the child can perform most daily activities.

-

Insertion of nasogastric and nasojejunal tubes

-

Gastrostomy, gastrojejunostomy and jejunostomy insertion

After healing, the stoma usually does not hurt. The child can perform most daily activities.

Side effects of enteral nutrition

The most common side effects of enteral nutrition are nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, diarrhoea, constipation and bloating.

There may be other side effects:

- Infection and irritation at the insertion site

- Probe misaligned or falling out

- Lung feeding formula

Most side effects can be avoided by following the care and nutrition instructions.

Feeding babies with tubes in place

The nutritionist is responsible for providing the baby with all the necessary nutrients. In children with cancer, an enteral feeding tube is often used in addition to what the child can eat normally. However, some patients have to enter all the nutrients through a tube.

The patient is prescribed a mixture containing:

- Calories

- Fluid

- Carbohydrates

- Fats

- Protein

- Vitamins and minerals

Standard formulas are suitable for many patients. For babies, it is preferable to use breast milk. Some children need special formulas that take into account their characteristics: the presence of allergies, diabetes or digestive problems.

It is very important for family members to work closely with a nutritionist. Nutritional needs may change due to changes in the child's health or side effects such as vomiting or diarrhea.

Types of enteral feeding

There are three types of enteral feeding - bolus, continuous and gravity.

Bolus feeding - large doses of the mixture are given to the patient by tube several times a day. This species is closest to the usual diet.

Continuous Power - Electronic pump delivers small doses of formula over several hours. Some children may need continuous feeding to reduce nausea and vomiting.

Gravity Feeding - A bag of formula is placed on the IV stand and a predetermined amount of formula is dripped through the tube at a slow rate. The duration of such nutrition depends on the needs of the patient.

Enteral feeding at home

Children can go home with a feeding tube. The doctors will ensure that family members know how to feed and care for the probe. Family members need to pay attention to the following issues:

- Weight gain or loss

- Vomiting or diarrhea

- Dehydration

- Infection

Formulas, Consumables, and Equipment Required:

- Formula: Most enteral formulas are sold ready-made.

Some are available as a powder or liquid to mix with water.

Some are available as a powder or liquid to mix with water. - Syringe

- Adapter tube (if the child has a button tube for long-term enteral nutrition)

- Pump (with continuous power)

- Feeding formula bag with tubing (for continuous feeding)

- IV Stand (Gravity Feed)

General tips for enteral feeding at home:

- Always wash your hands with soap and water before feeding your baby.

- Make sure the baby's head is above the stomach.

- Throw away any ready-made or homemade formulas that have been opened and kept in the refrigerator for 24 hours or more.

- Store mixed formulations in the refrigerator and discard after 24 hours.

- Ready-to-use formulas do not need to be refrigerated.

- Do not empty the syringe completely during feeding.

- Wash the syringe (and transfer tube, if used) with warm water and dishwashing detergent after each use.

- Watch for signs of nausea, vomiting, bloating or irritability while feeding.