Recycling baby food pouches

Here's How to Recycle All Those Empty Squeeze Pouches (for Free)

By

Sarah Showfety

Comments (2)Alerts

Photo: TonelsonProductions (Shutterstock)

If you have young kids, chances are, you’ve got some squeeze pouches in your house. While their mess-free convenience, light weight, and packability make them a parents’ dream, knowing how to responsibly dispose of them is not as dreamy.

Surprisingly, there are a few environmental plusses to their existence. Due to their light weight and small size, they’re relatively low-carbon to ship (as compared to traditional glass jars), and they don’t require the energy of refrigeration to keep them shelf-stable in the store. But since their construction relies on multiple materials like plastics, layered films, aluminum, and paperboard, mainstream American recyclers don’t have the systems to properly sort and peel the containers. Alas, into the trash bin they go.

Fortunately, there’s a way to reduce their presence in landfills. Check out these alternatives to tossing them out.

How to recycle plastic squeeze pouches

New Jersey-based TerraCycle has been collecting non-recyclable waste and turning it into new products since 2001. By partnering with more than 100 of the world’s largest brands (like Nestlé, Staples, Bic, and Brita), they’ve found a way to make recycling beneficial to both the environment and the images of multi-billion-dollar corporations.

Send in your empty squeeze pouches (and so many other things you didn’t think were recyclable, like Pringles tubs and toothbrushes) and they will shred, melt and chop the material into hard, rice-sized pellets that can be used in the manufacturing of other plastic items, such as benches and picnic tables.

While you don’t need to rinse the pouches, you do need to squeeze any remaining contents out prior to shipping. If you do choose to wash them out, be sure they’ve dried completely before sending. When you’re ready, create an account, print a shipping label, and drop it off at any UPS location.

When you’re ready, create an account, print a shipping label, and drop it off at any UPS location.

How many (and what brands) can I send?

There is no minimum number of pouches that TerraCycle will accept. However, if you send in more than ten pounds-worth, you’re eligible to earn points that, according to their website, can be redeemed for “charitable gifts, product bundles or a payment of $0.01 per point to the non-profit organization or school of your choice.” (Sounds like a great project for a school or non-profit youth group. They even have best practices and art for creating an effective neighborhood collection bin.)

And fear not, HappyBaby, Gerber, or Up & Up brand consumers: While GoGo squeeZ seems to be the anchor brand, in the FAQ on TerraCycle’s website they confirm, “You may collect any brand of waste for this free recycling program.” (They list “healthy snack plastic pouches and caps” in their “accepted waste” flier and a promotional picture includes other brands. )

)

Plum Organics also has a squeeze pouch cap recycling program that accepts caps from all manufacturers, not just their brand

Or...just make your own

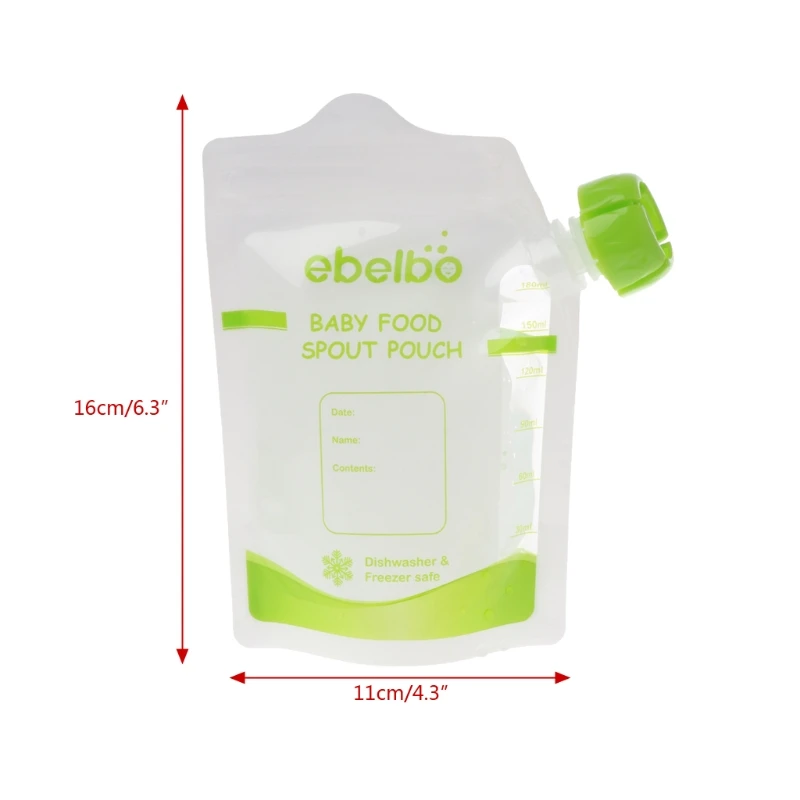

Of course, the other option is to avoid the single-use pouches altogether and go the DIY route. Amazon sells reusable squeeze pouches (with convenient front flaps for refilling). Load up on your favorite jar of apple sauce at Costco, or make some homemade tasty purees (with hidden vegetables, of course), and enjoy the magic of the flexible pouch without any guilt.

Can I recycle baby food pouches?

Have a few minutes to help out Grist’s favorite advice columnist? Please take our survey.

Q. Dear Umbra,

I’ve been using food pouches for my kids for a couple of years and have horrible guilt. Lately, I’ve been saving them and have been trying to figure out if they can be recycled. I think I can bring the tops to the Preserve Gimme 5 bin at Whole Foods, but it also looks like TerraCycle will take both the pouch and cap. But then I found an old article saying TerraCycle is all about greenwashing. Can you please help me figure this out?

But then I found an old article saying TerraCycle is all about greenwashing. Can you please help me figure this out?

Stephanie

Arlington

Reader support makes our work possible. Donate today to keep our climate news free. All donations matched!

- One Time

- Monthly

- $10

- $15

- Other

A. Dearest Stephanie,

Dearest Stephanie,

I don’t have any kids, and I’m no toddler. But I confess I’ve passed those baby/toddler food pouches at the grocery store on more than one occasion and thought, “Mmm, I wonder if I could get away with eating that as my afternoon snack.” I mean, roasted pumpkin and coconut rice? Pears, mangoes, and papayas? Don’t mind if I do!

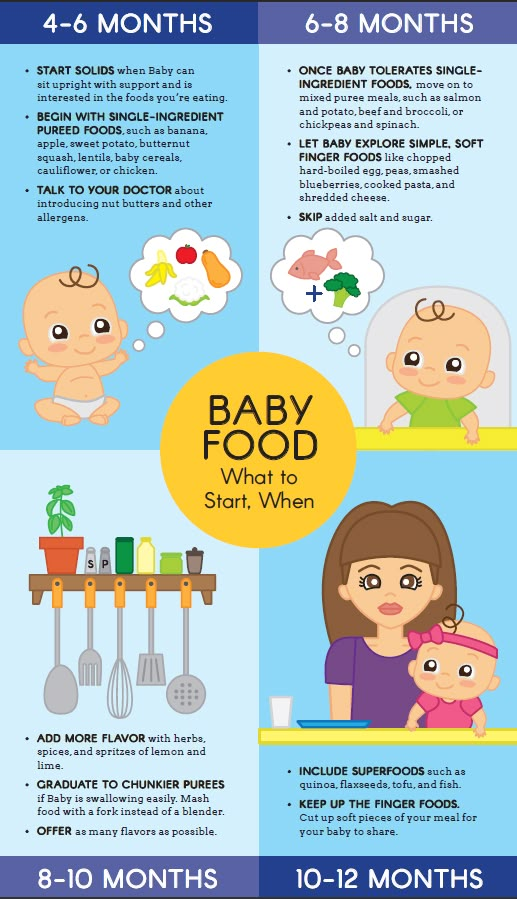

I can see the appeal of ready-to-eat treats in such packages even beyond the delectable-sounding flavors. Parents like ‘em because they’re a convenient, packable, (slightly) less messy way to keep those little mouths fed. Companies like ‘em because they’re shelf-stable and cheap to produce. And believe it or not, there are reasons for environmentalists to like ‘em, too. Their shelf-stableness saves on energy because they don’t need to be refrigerated; they’re much smaller and lighter than alternative packages, like glass jars, so they require fewer resources to make; and they’re also cheaper and less fuel-intensive to ship. All these benefits help explain why we’re seeing more and more foods, from trail mix to coffee to pickles, pop up in flexible pouches.

But you’re familiar with their major downside, Stephanie: Flexible pouches are very difficult to recycle. That’s because they’re often made of multiple layers of different materials — including plastics such as PET and PE, aluminum foil, and paperboard — glued together. Individually, some of these layers are easily recyclable; but lasagna’d together, recycling them becomes a complicated and pricey endeavor. It’s the same issue that bedevils those aseptic cartons for soup, soy milk, and the like.

You’re right that the tops, at least, are a bit easier to resurrect into new products. The ones made from #2 plastic are curbside recyclable in some cities (other places can’t accept them because they’re too small to be sorted efficiently). If you buy Plum Organics brand, then the #5 plastic caps, as you note, can be dropped off or mailed in to Preserve’s Gimme 5 recycling program. But the pouches are trickier, and the New Jersey–based TerraCycle recycling program is one of the few outfits that does accept kid pouches from a few brands.

Good news: I’ve seen nothing to make me think TerraCycle is greenwashing anything. In its model, consumers send in hard-to-recycle items; the company then chops them, melts them, and sells them to be made into things like benches and pallets. Other companies help pay for the process in exchange for the right to print “recyclable through TerraCycle” on their goodies. Some criticize TerraCycle on the grounds that this doesn’t encourage manufacturers to switch to easily recyclable packaging; TerraCycle counters that these lighter-weight packages are an overall environmental win (for all the reasons we discussed above), so it’s better to keep them in play.

My take? In a perfect world, nobody would use any throwaway packaging at all, so there would be no need for such a service. But we don’t live in such a world. Yes, it would produce less waste for you to make all your toddler snacks at home and feed them to the kids on reusable dishes. It would also produce less packaging waste if we all grew our own fruits and vegetables and baked our own potato chips. But that’s not doable for most people in this day and age. I say, reduce your consumption as best you can, reuse as best you can, and then recycle as a third line of defense. And shipping hard-to-recycle items to TerraCycle is better than landfilling them. (If your kids are real pouch fiends and you have the time for DIY puree, you can take it down one more notch by switching to these reusable pouches instead of disposables.)

But that’s not doable for most people in this day and age. I say, reduce your consumption as best you can, reuse as best you can, and then recycle as a third line of defense. And shipping hard-to-recycle items to TerraCycle is better than landfilling them. (If your kids are real pouch fiends and you have the time for DIY puree, you can take it down one more notch by switching to these reusable pouches instead of disposables.)

I absolve you of your guilt over squeezable pouches, Stephanie. They’re small fry, not one of the things worth much of your concern. Mom guilt has reached epic proportions in this country, so let’s make snack time, at least, a feel-good time for all.

Squishily,

Umbra

The only newsroom focused on exploring solutions at the intersection of climate and justice. Your support keeps our unbiased, nonprofit news free. All donations matched for a limited time.

The only newsroom focused on exploring solutions at the intersection of climate and justice. Your support keeps our unbiased, nonprofit news free. All donations matched for a limited time.

Your support keeps our unbiased, nonprofit news free. All donations matched for a limited time.

Donate Now Not Now

Next ArticleWe fact-checked what Trump and Clinton said about energy at the debate

Recycling plastic bags · Life Concept

A plastic bag is a convenient, practical and cheap product. But since this synthetic material is characterized by a long decomposition period and can create a big environmental problem, the issue of its disposal is extremely acute. The best measure to prevent environmental pollution is to sort and recycle polyethylene, rather than stop using it. In the process of processing, granules are obtained, which can later be used for the production of garbage bags, secondary shrink film, technical polyethylene film.

Commercial organizations, hotels, cleaning services, medical institutions and other organizations will be able to purchase plastic garbage bags from Concept Byta. It is one of the leading manufacturers of household goods in the Russian market. The range includes dozens of products. The main advantages of the products: high quality, affordable prices, excellent consumer properties.

It is one of the leading manufacturers of household goods in the Russian market. The range includes dozens of products. The main advantages of the products: high quality, affordable prices, excellent consumer properties.

4 trillion bags end up in the environment every year. They are not afraid of the effects of water, wind, low and high temperatures, organic compounds. Polyethylene causes the death of millions of birds, fish, marine mammals. For this reason, the use of bags as household packaging raises serious objections from environmentalists and is banned in many countries.

Polyethylene decomposes for up to 300 years. Under the influence of heat and sunlight, the material releases hazardous substances, which then enter the water and earth. Humanity must realize that its life and the life of future generations depend on the solution of environmental problems. And the most optimal solution will be the processing of polyethylene and its recycling.

Types of bags and features of their processing

- Polyethylene.

The material can be melted to a liquid state, then extruded. This property allows you to create new, durable and environmentally friendly products from it.

The material can be melted to a liquid state, then extruded. This property allows you to create new, durable and environmentally friendly products from it. - Cellophane. The material is not plastic, so it decomposes naturally. For disposal, it is better to put it in compost.

Russian collection points for plastic bags and films can be returned:

- packing bags, T-shirts;

- bubble wrap, greenhouse wrap, stretch wrap;

- spunbond bags;

- polyethylene foam;

- foil bags;

- sugar bags.

Bags made from biodegradable plastic or polyvinyl chloride will not be returned. Also, collection points are unlikely to accept shower curtains, tablecloths, baby stroller covers.

How plastic bags are recycled

Procedure steps:

- collection and sorting of raw materials. Most often, this is done manually;

- High pressure flush. In the process, raw materials are cleaned of contaminants;

- polyethylene grinding in a special unit for further processing;

- centrifuge dehumidification;

- complete heat treatment in a dryer.

After it, the raw materials are fully suitable for the production of products.

After it, the raw materials are fully suitable for the production of products.

Various products are made from recycled polyethylene. But it is not suitable for the production of sterile food packaging.

Important. With each subsequent processing, the quality of products decreases, so manufacturers try to use only primary raw materials.

You can also recycle plastic bags at home. The output will be dense sheets. They are suitable for use at home or in summer cottages. Sequence of actions:

- for bags it is necessary to cut off the handles and the bottom, and cut the sides;

- Fold the resulting rectangles in layers on a heat-resistant substrate covered with a sheet of parchment. No more than 5 bags should be used at a time;

- a stack of bags should be covered with parchment and ironed on medium temperature from the middle to the edges until they fuse together.

The sheets obtained after five-layer soldering can be joined, then denser layers will be obtained.

How separate waste collection will help save the environment from polyethylene pollution

Residents of Russia are used to throwing waste into a common bin, then it is taken to a landfill. There they will decompose for hundreds of years, poisoning the soil and water. In developed countries, a completely different approach to waste disposal is used: people sort the garbage, then it is sent for processing for reuse. We can learn from this experience and also start handing over packages to collection points. Polyethylene will get a second life, and we will prevent environmental pollution.

Polyethylene decomposes over a long period of time. Accumulating, it worsens the state of the environment. Recycling plastic bags will help to successfully solve this problem. The material obtained after processing can be used for the production of new plastic products. The collected raw materials are sorted, impurities are removed, and then melted until a homogeneous mass is obtained and granulated.

Plastic packaging recycling

Over the past few years, industry stakeholders have been working on a pilot initiative to see how flexible plastic packaging will perform in a large recycling facility.

In March 2019, after years of planning, research and engineering, the first test bales of , which would become a new product called rFlex , rolled off the assembly line at the Total Recycle plant, a large single-flow material recycling facility (MRF ) in Eastern Pennsylvania.

These bales and their pilot program represented a potential answer to a question that had long challenged processors, packers and plastics manufacturers: How can flexible plastic packaging, one of the fastest growing materials in the post-consumer waste stream, fit into the recycling system? not designed for this?

Flexible Plastic Packaging (FPP)—a broad category that includes plastic bags, wrappers, pouches, and films—was considered packaging that clogs sorting plants. Meanwhile, the variable blend of plastic resins used in these packages meant that her path to recycled plastic products was not an easy one.

Meanwhile, the variable blend of plastic resins used in these packages meant that her path to recycled plastic products was not an easy one.

“As a plastics manufacturer, we know how important packaging recycling is to our entire value chain, from our direct customers to end users, and we believe that recycling can help environmentalists,” said Jeff Wooster , director of sustainability at Dow, the company that supported the project. “This motivated us to start collaborating across the industry to address the challenges associated with FPP recycling.”

Over the next year, researchers will work to address these issues as part of the Recycling Pilot to explore ways to collect, separate and prepare flexible plastic packaging for recycling - all within the context of a typical US recycling program.

Materials Recovery for the Future (MRFF), a collaborative research program sponsored by leading players in the flexible packaging value chain, was launched in 2015 with a comprehensive program focused on recycling flexible packaging and ensuring that the recycling system is value-conscious material.

The first few years of the program included basic research led by recycling and sustainability consultancy RRS to prove how flexible packaging works in single-stream recycling systems, how optical sorters can be used for separation, and how what the economics of recycling flexible plastic packaging would look like if it were distributed throughout the US.

At the same time, the potential end market uses of this package were investigated and sorting studies assessed the products that could eventually be sold.

By 2018, studies at major recycling centers across the country showed promising results . The flexible packaging behaved predictably in sorting, and the wrap screens solved most clogging problems. Optical sorters at test facilities were able to identify and extract flexible plastic packaging from the trash stream. And while the equipment needed would cost millions of dollars, it had the potential to create new processed products, improve the quality of other products, and increase the level of automation and processing flexibility.

"Our previous study was to see if this material could sort ," said Chris King, senior engineer at RRS. “We noticed that the anti-wrap sieves worked well, and the consistent flow of FPP with 2D material meant there was a real opportunity to recycle it.”

But other questions could only be answered after specific tests of this concept. How well could the system function day in and day out, in the grueling environment of a continuously operated recycling center? What would a real mix of package types look like if it was collected from residents rather than modeled from sales data? And will it produce bales that could be sold to real end markets?

The pilot program required a large investment, but it was successful , which allowed the group to significantly accelerate research in a short time.

In June 2018, the MRFF project team announced that it had found a recycling partner. Total Recycle, owned by J.P. Mascaro and Sons, was to install four optical sorters and peripherals on its existing fiber optic lines to retrieve flexible packaging, which it will collect from residents as part of a formalized recycling program in certain communities.

As of January 2019, Total Recycle was undergoing an upgrade. The FPP sorting system, purchased and installed by Van Dyk Recycling Solutions, included Tomra Autosort 4 optical sorters installed on each of three fiber optic lines to extract FPP from raw materials. These high-end optical sorters feature a wide design that allows them to process material from the entire conveyor belt and operate at high speeds with the best possible material distribution.

The fourth Tomra Autosort 4 has cleared the FPP stream by extracting the remaining packs. Finally, a Lubo Paper Magnet was used to separate rigid items such as containers from the FPP stream.

This system reconfigured the entire processing and effectively removed FPP from the fiber stream with minimal need for manual quality control. But how well will it be able to perform its dual function over time - consistently capturing as many FPPs as possible while minimizing any material wastage?

In March 2019, the rFlex system was launched: optical sorters screened out any FPP that entered the recycling center. However, when cutting bales made from this material, a problem arose. The system was capturing too much unwanted material: audit results showed that less than half of the bales consisted of target FPP. Diverse non-target fiber accounted for 43% of the bale, far from the expected result of 15% or less. Pollution in the form of flattened containers and various garbage accounted for another 15%.

However, when cutting bales made from this material, a problem arose. The system was capturing too much unwanted material: audit results showed that less than half of the bales consisted of target FPP. Diverse non-target fiber accounted for 43% of the bale, far from the expected result of 15% or less. Pollution in the form of flattened containers and various garbage accounted for another 15%.

“It would be great to see perfect performance from day one,” said J.P. Mascaro, Sr., Senior Director of Waste Management at J.P. Mascaro & Sons. “But that’s why it’s so important to do this pilot project: testing the solution in real conditions can reveal problems that you would not have noticed in a few days of testing.”

Monitoring the system in operation revealed what was causing the rFlex bale quality problems.

Rainy spring weather caused uncoated recycled material to get wet; wet paper clumped, making it difficult for optical sorters to separate the FPP. After the rains ended, the material became easier to sort. This finding emphasized the importance of switching to covered carts for residential material collection.

After the rains ended, the material became easier to sort. This finding emphasized the importance of switching to covered carts for residential material collection.

Another fix was to balance between automatic and manual sorting . The fourth optical sorter, which cleaned paper from the rFlex stream, was initially calibrated less aggressively. Noticing this, the recycling center recalibrated the sorters and added a manual checkpoint-like quality control station so people can select any missed FPP for the rFlex roll after the optical sorters do their job.

The system optimization process took nine months but it was worth it. At the end of the adjustment period, the fiber level in the bale was one quarter of what it was at the beginning. The average bale FPP was 77%, very close to what was achieved in pilot plants back in 2016, but this time it was consistently produced under real conditions.

Flexible plastic packaging comes in a variety of shapes and sizes, from baby food bags to large bags of dog food. The MRFF pilot project was aimed at capturing all of this range, with rare exceptions (such as very small packages or anything made of PVC). It also aimed to ensure that if FPP was accepted into recycling programs, it would successfully find its way to the rFlex bale, rather than end up as a residue that contaminates other processed products.

The MRFF pilot project was aimed at capturing all of this range, with rare exceptions (such as very small packages or anything made of PVC). It also aimed to ensure that if FPP was accepted into recycling programs, it would successfully find its way to the rFlex bale, rather than end up as a residue that contaminates other processed products.

In order to understand how this is really possible, the RRS research team used RFID technology to track package samples at the recycling center and calculate how many of them made it into the rFlex bale. This RFID test was repeated at the beginning, middle and end of the pilot to monitor progress. Each test included labeling thousands of packages, adding them to the recycling system over several days of testing, and analyzing which labels were read by each of the 10 RFID readers at specific locations in the recycling center.

RFID testing process identified areas of progress and areas for improvement . First, the test showed a successful capture of the majority of packets and an improvement in the process with an average capture rate of over 70% in two subsequent tests. Second, some packets were captured very efficiently, with capture rates of 90% by the end of the pilot for the most common retail packets.

First, the test showed a successful capture of the majority of packets and an improvement in the process with an average capture rate of over 70% in two subsequent tests. Second, some packets were captured very efficiently, with capture rates of 90% by the end of the pilot for the most common retail packets.

"RFID testing helps us see the strengths and weaknesses of the system," said King. “Once you know what it is, you can work on improving it.”

However, it was much more difficult for the system to capture the smaller packets, which were more affected by service problems, weather, and some other factors. This was especially noticeable in the third test: when small bags of baby food were fed into the system, many of them ended up in areas of heavy wear on the disk sorter and could not get into the rFlex bale. This did not happen with large packages.

Further research is ongoing to improve sorting smaller bags to bring it up to the high performance sorting level of large FPP products.

Due to the technical feasibility of FPP sorting, another line of research was devoted to economic details .

In 2018, RRS developed a financial model that explores the potential benefits of recycling FPP . For recycling centers, the challenges were threefold: 1) moving FPP from landfill waste to a potentially profitable bale; 2) reduction of labor costs for cleaning the fibers of raw materials; 3) improving the quality of processing, even with an increased content of FPP in the feedstock. Although the economy is considered to be the most sustainable in areas with higher landfill costs, due to the lack of waste disposal costs.

As the pilot project progressed, these potential benefits were realized . Beginning in September 2019, residents of local communities were instructed to gradually begin to include FPP in roadside disposal. FPP volumes have increased, but even after the implementation of the quality control measures mentioned above, the amount of labor required to operate the system has decreased by 38%. Before and after audits of processed products, there was also a significant decrease in the share of contamination - from 1.4% to 0.3% in old newsprint (ONP) and from 1.6% to 0.5% in blended paper.

Before and after audits of processed products, there was also a significant decrease in the share of contamination - from 1.4% to 0.3% in old newsprint (ONP) and from 1.6% to 0.5% in blended paper.

The addition of an additional category of recyclables does challenge some of the latest trends in the market, but the MRFF pilot project suggests it could pay off. Given the efficiency benefits, the economic model shows that FPP recycling can be a low-cost addition to residential waste collection contracts. And as additional markets develop for rFlex bales, FPP processing could grow into a profitable business in its own right.

But what could be the end markets for the rFlex ? For the MRFF study, this remained a key unresolved issue that intersected with every aspect of the pilot project.

After months of bale production efforts and research to determine their exact composition, two main market paths emerged: mixed bale markets and plastic-only markets. Markets for mixed bale materials include manufacturers of building materials using a combination of fibers, plastics and (in some cases) other materials such as glass and filler. In the plastics-only markets, the fiber from the bales is removed by wet or dry laundering, and then pellets or molded durable products are made with the plastic component.

Markets for mixed bale materials include manufacturers of building materials using a combination of fibers, plastics and (in some cases) other materials such as glass and filler. In the plastics-only markets, the fiber from the bales is removed by wet or dry laundering, and then pellets or molded durable products are made with the plastic component.

“The rFlex End Markets Network that grew out of this research program is critical,” said Susan Graff, vice president of RRS and director of project research for MRFF. “This is a group that connects the demand for recycled plastic products with the MRFF offer to build a recycling economy for flexible packaging raw materials. Through rFlex testing and peer review, we have new opportunities for product manufacturing using low-cost, high-performance recycled raw materials that can replace virgin materials.”

By spring 2020, bales have been shipped to local, regional and international companies interested in exploring rFlex applications. As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, some of these trials ceased and results were not released until after the results of the pilot study were published. Successful test results followed in the mixed bale markets and rFlex bales were purchased for the pilot plant to be used in the coverboard industry.

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, some of these trials ceased and results were not released until after the results of the pilot study were published. Successful test results followed in the mixed bale markets and rFlex bales were purchased for the pilot plant to be used in the coverboard industry.

“We think it's important to define the value of flexible packaging for post-consumers. This means getting it back into service as a useful and functional end product,” said Brent Heist, Packaging Materials Leader at Procter & Gamble and Chairman of the MRFF Project.

By June 2020, 18 months after the equipment was installed, the results of the pilot project were published . The report described progress in many areas, as well as plans for further improvement of the work.

An FPP capture rate of 74% is being considered with additional modifications to achieve the 90% target. End-market testing is ongoing, and an inventory of the life cycle impact and costs of sorting and recycling FPP is underway to test its effectiveness.

These unanswered questions motivated to continue the RRS study of MRFF as part of the REMADE Institute award-winning project. The project, titled "Determining the Material, Environmental and Economic Efficiency of Sorting and Recycling Mixed Flexible Packaging and Plastic Film", will examine the impact of rFlex production, transportation and recycling. The project, scheduled for completion in 2021, will publish interim results on an ongoing basis, starting with engineering support and an additional RFID test in August 2020 to further improve the composition of the recycled material bale.

Heist added: “Our report represents a milestone, but not the end of MRFF. We are pleased that the work to develop the market for flexible packaging reuse will continue with the American Chemistry Council and the REMADE Institute to expand our knowledge and consolidate our achievements to date.”

The qualities of flexible packaging that make it environmentally friendly - its light weight and the small amount of raw materials needed for its production - motivated its use, but made it difficult to recycle.