Thyroid mother can feed milk to baby

Breastfeeding and Thyroid Problems: FAQ • KellyMom.com

By Kelly Bonyata, IBCLC

- Is it safe for a mom with thyroid disease to breastfeed?

- Low thyroid levels (hypothyroid)

- High thyroid levels (hyperthyroid)

- Thyroid autoantibodies

- Can breastfeeding prevent some thyroid problems?

Is it safe for a mom with thyroid disease to breastfeed?

Yes. Even if mom’s thyroid levels are not controlled by medication (or are in the process of being controlled) it is safe for mom to breastfeed her baby.

Low thyroid levels (hypothyroid)

Moms who are hypothyroid have low thyroid hormone levels and elevated TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) levels. Symptoms include cold intolerance, weight gain, dry skin, thinning hair, poor appetite, fatigue, depression and reduced milk supply.

Now infants can get

all their vitamin D

from their mothers’ milk;

no drops needed with

our sponsor's

TheraNatal Lactation Complete

by THERALOGIX. Use PRC code “KELLY” for a special discount!

Per Medications and Mothers’ Milk (Hale 2017, p. 928), “Thyrotropin, TSH) is known to be secreted into breastmilk, but in low levels. Virtually none of it would be orally bioavailable or transferred into human milk. Because TSH is significantly elevated in hypothyroid mothers, if present in milk at high levels, it could theoretically cause a hyperthyroid condition in the breastfeeding infant.” However, Hale goes on to cite a study which found only low levels of TSH in the breastmilk of a mom with extremely elevated TSH levels. Hale’s recommendations report no pediatric concerns via milk, and state that “Breastfeeding by hypothyroid mother[s] is permissible.”

Untreated low thyroid levels in mom may result in a decrease in milk supply and sometimes poor weight gain in baby (due to low milk supply). Per Breastfeeding and Human Lactation (Riordan & Wambach 2010, p. 522-523), “If replacement therapy of thyroid extract… is adequate, the relief of the symptoms and an increase in the milk supply can be quite dramatic. ”

”

High thyroid levels (hyperthyroid)

Moms who are hyperthyroid have elevated thyroid hormone (usually T4) levels. Symptoms include weight loss (despite an increased appetite), nervousness, heart palpitations, insomnia, and a rapid pulse at rest.

Hyperthyroidism is not a contraindication for breastfeeding. Per Medications and Mothers’ Milk (Hale 2017, p. 558-559, 564-565), only exceedingly low levels of thyroid hormones (both T4/levothyroxine and T3/liothyronine) transfer into breastmilk.

In animal studies, high thyroid levels interfered with milk let-down (Lawrence & Lawrence 2011, p. 570-574).

Thyroid autoantibodies

Mothers who have the autoimmune forms of thyroid disease will usually have thyroid autoantibodies present in their blood. Hypothyroidism is most commonly caused by Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, an autoimmune thyroid disease in which the immune system attacks and destroys the thyroid gland, resulting in underproduction of thyroid hormone. Another common autoimmune thyroid disease is Grave’s Disease, which is a leading cause of hyperthyroidism; in this disease the antibodies attacking the thyroid gland cause growth of the gland and overproduction of thyroid hormone. Some mothers may be worried that these antibodies may pass into breastmilk and harm baby, however this is not a concern. The thyroid autoantibodies are IgG immunoglobulins, which are too large to pass into breastmilk. Continuing to breastfeed will only benefit your baby, as babies who are artificially fed are at increased risk of developing autoimmune thyroid disease themselves.

Another common autoimmune thyroid disease is Grave’s Disease, which is a leading cause of hyperthyroidism; in this disease the antibodies attacking the thyroid gland cause growth of the gland and overproduction of thyroid hormone. Some mothers may be worried that these antibodies may pass into breastmilk and harm baby, however this is not a concern. The thyroid autoantibodies are IgG immunoglobulins, which are too large to pass into breastmilk. Continuing to breastfeed will only benefit your baby, as babies who are artificially fed are at increased risk of developing autoimmune thyroid disease themselves.

Can breastfeeding prevent some thyroid problems?

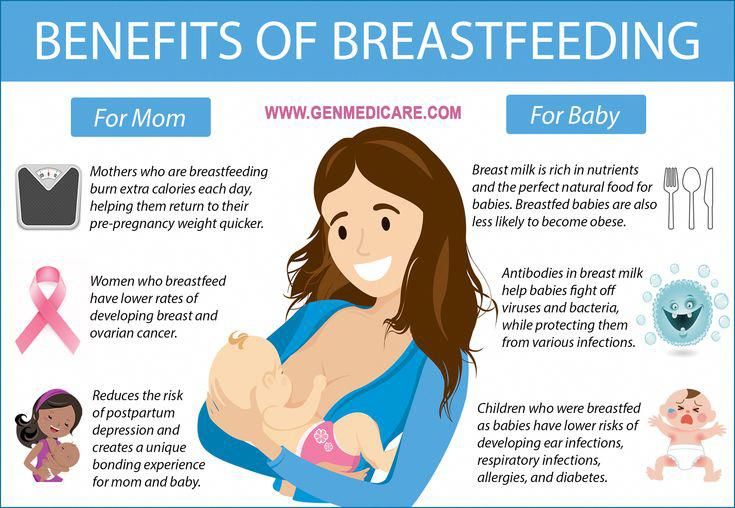

There is evidence that breastfeeding can help to prevent thyroid problems in both mom and baby.

- Breastfeeding helps to prevent autoimmune thyroid disease (Fort 1990).

- Breastfeeding may help to prevent thyroid cancer in mom (Mack 1999).

Breastfeeding and Thyroid Problems: Links

Breastfeeding and Thyroid Problems: Studies and References

Breastfeeding and Thyroidism - La Leche League International

The thyroid is a gland found in the front of your neck. It secretes hormones that play an important part in lactation by regulating prolactin and oxytocin.

It secretes hormones that play an important part in lactation by regulating prolactin and oxytocin.

Thyroid disorders impact a woman’s health in a variety of ways. When the thyroid is not functioning correctly, it can impact milk production. There is also connection between thyroid disorders and autoimmune problems. The immune system is suppressed during pregnancy to protect your baby. This is a good thing. You don’t want your body reacting to your growing baby as a foreign invader! Problems with the thyroid can begin before or during pregnancy, in the postpartum period, or later in life. They can also occur along with other medical conditions, which can make diagnosis and treatment more challenging.

Thyroid disease is diagnosed through blood tests that measure the levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TCH) triisdothyrine (T3)/tetra-iodothyronine (thyroxine or T4). It is also recommended that iodine levels be monitored and treated, if they are not at appropriate levels. Let your obstetrician and personal care physician know if there is a family history of thyroidism.

Let your obstetrician and personal care physician know if there is a family history of thyroidism.

The most common forms of thyroidism are hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and postpartum thyroid dysfunction.

Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid)- Indicated when the TSH level is high and T3/T4 levels are low.

- Symptoms – dry skin, sensitivity to cold, “baby blues” and/or depression, fatigue, hair loss, lack of energy, forgetfulness, constipation, increased menstrual frequency and flow, mild enlargement of the thyroid.

- Most common form is Hashimoto’s disease.

- Thyroid hormone replacement is a common form of treatment especially during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- In pregnancy, this can result in pregnancy-induced hypertension and low birth weight.

- Mothers with hypothyroidism are at risk for delayed or insufficient milk production.

- Studies also indicate there may be a negative effect on oxytocin.

- Indicated when the TSH level is low and the T3/T4 levels are high.

- Symptoms – racing heart, feeling nervous/anxious, sweating, tremors, muscle cramps, fatigue, tired, run down, weight loss, sensitivity to heat, diarrhea, decreased menstrual frequency and flow, mild enlargement of the thyroid.

- Most common form is Grave’s disease.

- Pregnancy can induce a mild form due to the increased rates of clearance of T3/T4 levels in the blood plasma. Some mothers with hyperthyroidism may notice an easing of symptoms in the second and third trimesters, but symptoms can rebound after delivery.

- Mothers with hyperthyroidism are at risk for premature delivery, pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction and increased mortality for mother and baby.

- Studies also indicate there may be negative impact on prolactin and oxytocin concentrations.

- Treatments:

- Studies have indicated that propylthiouracil (PTU) is the drug of choice for a breastfeeding mother in this instance.

It is excreted in small amounts into breastmilk and does not impact baby’s thyroid function.

It is excreted in small amounts into breastmilk and does not impact baby’s thyroid function. - Methimazole is an accepted option, baby should be monitored frequently.

- Studies have indicated that propylthiouracil (PTU) is the drug of choice for a breastfeeding mother in this instance.

- Four types:

- Postpartum thyroid dysfunction (PPT)

- Postpartum Grave’s disease

- Postpartum pituitary infarction (Sheehan’s syndrome) – often associated with excessive blood loss during/after delivery

- Lymphocytic hypophysitis

- Occurs in about 5-7% of all pregnancies.

- Women with diabetes mellitus type 1 are at three times the risk.

- Women who smoke are at three times the risk.

- Symptoms – intolerance to cold, dry skin, lack of energy, impaired concentration, aches and pains.

- Typically starts with aspects of hyperthyroidism that can last up to several weeks and the transition to hypothyroidism, which can last for several months. This state is more obvious clinically, leading to treatment.

Thyroid issues often cause difficulty with milk supply and with milk removal. Mothers may find their thyroid levels change with pregnancy and childbirth, which is why frequent testing of mother is recommended. Depending on the medication, your baby’s levels may also need to be checked regularly postpartum.

Suggested management to support breastfeeding- Regular follow-up with physician, regular screening for hypothyroidism in first year.

- Important to work on improving milk removal.

- Pitocine/oxytocin nasal spray – may provide the extra hormone needed to eject milk.

- Massaging breast – massage from outer reaches of the breast toward the nipple may make more milk available.

- Breast compressions during feedings – mechanically increasing internal pressures may help propel milk from the breast.

- Galactagogues – effective only if milk can be removed and thyroid levels are in balance, then can be useful as supportive treatment.

- Delay any radioactive tests or treatments until no longer breastfeeding if at all possible. If a scan using a radioactive material must be done, request the use of a radioactive material with the shortest half-life, which will result in the shortest interruption of breastfeeding.

- It is possible to resume breastfeeding immediately after a scan using contrast dye as the dye is not absorbed.

- Observe the cues of effective feeding:

- Adequate output.

- Hearing swallows.

- Breasts fuller before feeding and softening with feeding.

- Observe baby’s weight gain – that it remains consistent throughout the first year.

- Continue with any thyroid medications as prescribed.

- Check thyroid levels frequently to maintain levels at the upper part of the normal range.

- Communicate your treatment to all physicians involved in your care and encourage them to coordinate care together.

American College of Radiology. Manual on Contrast Media, p.102-103.

https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Clinical-Resources/Contrast_Media.pdf, accessed Mar 15, 2018

Hale,Thomas. https://www.infantrisk.com/

Lawrence RA and Lawrence RB. Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession, 7th edition Maryland Heights, MO, 2011, and 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016.

Mohrbacher N. Breastfeeding Answers: a guide for helping families, 2nd edition. Arlington Heights, IL, 2020: Nancy Mohrbacher Solutions.

Wambach K and Spencer B. Breastfeeding and Human Lactation, 6th edition. Burlington, MA, 2021: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Momotani N1, Yamashita R, et al. Thyroid function in wholly breast-feeding infants whose mothers take high doses of propylthiouracil. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000 Aug;53(2):177-81. accessed Mar 15, 2018.

Speller, E. , Brodribb, W 2012, Breastfeeding and Thyroid disease: A literature review, Breastfeeding Review 20(2),41-47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22946151

, Brodribb, W 2012, Breastfeeding and Thyroid disease: A literature review, Breastfeeding Review 20(2),41-47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22946151

RECURRENCE OF DIFFUSIVE TOXIC GOITER OR POSTPARTUM THYROIDITIS? — "InfoMedPharmDialogue"

Skip to content THYROTOXICOSIS IN THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD: RECURRENCE OF DIFFUSIVE TOXIC GOITER OR POSTPARTUM THYROIDITIS?POSTPARTUM THYROTOXICOSIS: RECURRENCE OF DIFFUSIVE TOXIC GOITER OR POSTPARTUM THYROIDITIS?

Patient H., 27 years old, sought a consultation with an endocrinologist in November 2019, 5 months after an urgent delivery, with complaints of mild weakness, palpitations, sleep disturbances, and hair loss. Breastfeed. Takes multivitamins for pregnant and lactating women. She came to the appointment with the results of a hormonal examination, corresponding to manifest thyrotoxicosis, and a recommendation to stop lactation and start taking thyreostatics.

From the anamnesis

Anna SHVEDOVA, endocrinologist at the Neplacebo clinic, Voronezh

2.5 years ago, the patient was troubled by similar symptoms. The examination revealed persistent subclinical thyrotoxicosis and elevated levels of antibodies to TSH receptors (TSH less than 0.1 mIU/l, free fractions of T3 and T4 within the reference values, AT to rTTH 3.5 U/l at a rate of up to 1 U/l) . Conclusion of ultrasound of the thyroid gland from 2017: volume 17 ml, diffuse changes in the thyroid tissue, diffusely increased vascularization. A diagnosis of diffuse toxic goiter was established, tyrosol was prescribed, which the patient took for 9months under the control of hormonal status. After cancellation, euthyroidism persisted, after 6 months pregnancy occurred, the level of thyroid hormones and TSH during pregnancy was within the reference range. The pregnancy ended with the birth of a healthy full-term baby. 4 months after birth, the symptoms described above appeared. The patient has no chronic somatic diseases.

The patient has no chronic somatic diseases.

Test results from November 2019: TSH 0.01 mIU/l (reference 0.4-4.0), fT4 39.9 pmol/l (reference 9–22). Ultrasound of the thyroid gland: an increase in volume up to 22 ml, pronounced diffuse changes. With these results, the patient first turned to an endocrinologist at another clinic, and she was prescribed tyrosol at a dose of 30 mg per day with a recommendation to urgently stop lactation and transfer the child to artificial feeding. The patient did not want to stop breastfeeding and asked me for a second opinion.

Second opinion

On examination: satisfactory condition. Height 164 cm, body weight 60 kg, weight loss 5 months after birth - 2 kg. Mild symptoms of thyrotoxicosis: tachycardia 92 beats per minute, moist skin, fine tremor of the fingers in the Romberg position. The thyroid gland is compacted, diffusely enlarged to the 1st stage, painless. There were no signs of endocrine ophthalmopathy.

Taking into account the absence of a pronounced clinic of thyrotoxicosis and signs of ophthalmopathy, as well as the timing of the onset of symptoms (the first 6 months after delivery), it was concluded that differential diagnosis is necessary between the recurrent course of Graves' disease and the thyrotoxic phase of postpartum thyroiditis.

An additional examination was scheduled: determination of the level of antibodies to the TSH receptor. The level of antibodies to rTTH was slightly elevated (1.8 U/l with a reference of less than 1.0 U/l and a "grey zone" of 1–1.5 U/l). Thyroid scintigraphy was discussed with the patient, but it turned out to be inconvenient due to the need to pump during the day after the study. Since a slight increase in the level of total antibodies to rTSH is also possible with postpartum thyroiditis, it was decided to refrain from prescribing thyreostatics and conduct a second examination and hormonal examination after 4–6 weeks.

On examination one month later (and 6 weeks after laboratory confirmation of thyrotoxicosis), symptoms and complaints characteristic of thyrotoxicosis were not revealed. The patient suffers from headaches and drowsiness. Weight gain per month +2 kg. The results of the control examination: TSH 0.078 mIU/l, fT4 8.42 (reference 9–22 pmol/l). The conclusion was made about the onset of the hypothyroid phase of postpartum thyroiditis - free T4 is already below the reference values, but the previously suppressed TSH level has not yet "managed" to rise. Since laboratory errors in measuring T4 are more common than in determining TSH, the patient was recommended to repeat the study after 2-4 weeks "on a clean background".

Since laboratory errors in measuring T4 are more common than in determining TSH, the patient was recommended to repeat the study after 2-4 weeks "on a clean background".

A history of Graves' disease does not rule out another cause of thyrotoxicosis in the puerperium

Examination results after 3 weeks: TSH 4.5 mIU/l, free T4 6.37. If we had waited longer, we would no doubt have seen a significant increase in TSH, which would correspond to a significant decrease in the level of free thyroxine. We did not wait, because hypothyroidism was symptomatic, and the state of lactation is another reason to compensate for the hypothyroid phase of postpartum thyroiditis (both subclinical and overt hypothyroidism can negatively affect lactation). Thyroxine was prescribed at a calculated dose of 1.6 μg per kg of body weight (100 μg per day), after 2 months the result of TSH was 2.7 mIU / l. 6 months after the start of treatment with TSH 0.8 mIU / l, a decrease in the dose of thyroxine is recommended. Subsequently, the thyroid function was restored, and the drug was discontinued, at the last examination (June 2021) subclinical hypothyroidism was registered, TSH and fT4 control was recommended after 3 months “against a clean background”.

Subsequently, the thyroid function was restored, and the drug was discontinued, at the last examination (June 2021) subclinical hypothyroidism was registered, TSH and fT4 control was recommended after 3 months “against a clean background”.

Discussion

During the first year after childbirth, women often manifest autoimmune diseases, including autoimmune thyroid diseases that cause thyrotoxicosis. The doctor has an important task to make a differential diagnosis between two common causes of thyrotoxicosis in the postpartum period - the thyrotoxic phase of postpartum thyroiditis and diffuse toxic goiter (Graves' disease), since the treatment tactics for these diseases differ dramatically. We know that in the first 6 months after delivery, postpartum thyroiditis is more common, and after the first 6 months - Graves' disease, that Graves' disease is characterized by an increase in the level of antibodies to the TSH receptor and more clinically and laboratory pronounced thyrotoxicosis, and that the combination of thyrotoxicosis with endocrine ophthalmopathy and (much rarer) pretibial myxedema indicates Graves disease. However, in some cases, it is not easy to establish a diagnosis. For example, a slight increase in the level of antibodies to the TSH receptor is also possible with postpartum thyroiditis, and an indication of successful conservative treatment of Graves' disease in the past makes the doctor think about a relapse of the disease after childbirth (which happens very often). However, a history of Graves' disease does not rule out another cause of thyrotoxicosis in the postpartum period.

However, in some cases, it is not easy to establish a diagnosis. For example, a slight increase in the level of antibodies to the TSH receptor is also possible with postpartum thyroiditis, and an indication of successful conservative treatment of Graves' disease in the past makes the doctor think about a relapse of the disease after childbirth (which happens very often). However, a history of Graves' disease does not rule out another cause of thyrotoxicosis in the postpartum period.

It is important to make sure of the diagnosis and the need to prescribe thyreostatics, because the cost of a mistake is very high

It is important to make sure the diagnosis and the need to prescribe thyreostatics, because the cost of error is very high: the appointment of thyrostatic therapy is fraught with serious side effects, the treatment is prescribed for a long time and is often accompanied by a recommendation to stop breastfeeding. The validity of this recommendation is very doubtful: all over the world, if a woman wants to maintain lactation, the tactic of prescribing small doses of thyreostatics has been adopted, since the literature has not described a single case of side effects or the development of hypothyroidism in breast-fed infants whose mothers took thiamazole at a dose of 20 mg or less, or propylthiouracil at a dose of 250 mg or less. This position is reflected in the clinical guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and treatment of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period (2017), in the recommendations of the European Endocrinological Society for the treatment of Graves' disease (2018), as well as in many articles and publications. However, in Russia the situation is legally ambiguous. In Russian clinical guidelines for the treatment of thyrotoxicosis with diffuse and nodular goiter, the use of thyreostatics during lactation is not specified. The Russian instructions for thiamazole have recently been amended, and now it indicates the possibility of continuing breastfeeding while taking the drug in small doses; in the instructions for propylthiouracil, both pregnancy and the period of breastfeeding are still considered contraindications. If my patient had a confirmed relapse of Graves' disease, then we would discuss the maintenance of lactation and the appointment of thiamazole in a small daily dose divided into 2-3 doses (the drug is taken after the next feeding, the next feeding is recommended to be postponed for 3-4 hours), as well as would plan radical treatment of thyrotoxicosis.

This position is reflected in the clinical guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and treatment of thyrotoxicosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period (2017), in the recommendations of the European Endocrinological Society for the treatment of Graves' disease (2018), as well as in many articles and publications. However, in Russia the situation is legally ambiguous. In Russian clinical guidelines for the treatment of thyrotoxicosis with diffuse and nodular goiter, the use of thyreostatics during lactation is not specified. The Russian instructions for thiamazole have recently been amended, and now it indicates the possibility of continuing breastfeeding while taking the drug in small doses; in the instructions for propylthiouracil, both pregnancy and the period of breastfeeding are still considered contraindications. If my patient had a confirmed relapse of Graves' disease, then we would discuss the maintenance of lactation and the appointment of thiamazole in a small daily dose divided into 2-3 doses (the drug is taken after the next feeding, the next feeding is recommended to be postponed for 3-4 hours), as well as would plan radical treatment of thyrotoxicosis. Usually mothers of infants prefer to delay radical treatment for 1-2 years, when the separation of the child from the mother becomes less painful for both.

Usually mothers of infants prefer to delay radical treatment for 1-2 years, when the separation of the child from the mother becomes less painful for both.

Breastfeeding and Thyroid Problems: Frequently Asked Questions

?Previous Entry | Next Entry

Kelly Bognata, IBCLC

Updated 01/13/2018

Is it safe for a woman with thyroid disease to breastfeed?

Yes. Even if the mother's thyroid hormone (thyroid) levels are not being controlled by medication (or are being controlled at the moment), a woman can safely breastfeed her baby.

Low thyroid hormone levels (hypothyroidism)

Hypothyroid mother has low thyroid hormone levels and elevated TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone). Symptoms include cold intolerance, weight gain, dry skin, thinning hair, poor appetite, fatigue, depression, and decreased milk production.

According to " Medications and Mothers' Milk " (Hale, 2017, p. 928): "Thyrotropin (TSH) is known to be found in small amounts in breast milk. Practically when taken orally, due to bioavailability, TSH will not enter breast milk. Since TSH is significantly elevated in mothers with hypothyroidism, its presence in milk in large quantities could theoretically cause a hyperthyroid state in an infant. " However, Dr. Hale cites a study that found only low levels of TSH in the breast milk of mothers with extremely elevated TSH levels. Hale's guidelines state that there is no information about pediatric problems associated with breast milk and state that "breastfeeding is acceptable in maternal hypothyroidism."

If left untreated and corrected for low thyroid hormone levels, the mother's milk production may decrease and the baby may slowly gain weight (due to insufficient milk supply). According to " Breastfeeding and Human Lactation " (Riordan & Wambach 2010, p. 522-523): "If replacement therapy with thyroid extract (hormone preparations from porcine thyroid gland) ... is adequate, symptom relief and milk production increase can be quite significant ".

522-523): "If replacement therapy with thyroid extract (hormone preparations from porcine thyroid gland) ... is adequate, symptom relief and milk production increase can be quite significant ".

High thyroid hormone levels (hyperthyroidism)

In hyperthyroidism, the mother has elevated thyroid hormone levels (usually T4). Symptoms include weight loss (despite increased appetite), nervousness, palpitations, insomnia, and an increased resting heart rate.

Hyperthyroidism is not a contraindication for breastfeeding. According to " Medications and Mothers' Milk " (Hale, 2017, pp. 558-559, 564-565), only extremely low levels of thyroid hormones (both T4/levothyroxine and T3/liothyronine) pass into breast milk.

Animal studies have shown that high levels of thyroid hormone interfere with milk production (Lawrence & Lawrence 2011, pp. 570-574).

Thyroid autoantibodies

Mothers with autoimmune forms of thyroid disease usually have thyroid autoantibodies in their blood. Hypothyroidism is most commonly caused by Hashimoto's thyroiditis, an autoimmune thyroid disease in which the immune system attacks and destroys the thyroid gland, resulting in insufficient production of the thyroid hormone (T4). Another common autoimmune thyroid disease is Graves' disease, which is the leading cause of hyperthyroidism. In this disease, antibodies that attack the thyroid gland cause its growth and hyperproduction of thyroid hormones (T3, T4). Some mothers may be concerned about the possibility of these antibodies passing into breast milk and potentially harming the baby, but this is not a problem. Thyroid autoantibodies are IgG immunoglobulins that are too large to pass into breast milk. Continued breastfeeding will only benefit your baby, as formula-fed babies themselves are at increased risk of autoimmune thyroid disease.

Hypothyroidism is most commonly caused by Hashimoto's thyroiditis, an autoimmune thyroid disease in which the immune system attacks and destroys the thyroid gland, resulting in insufficient production of the thyroid hormone (T4). Another common autoimmune thyroid disease is Graves' disease, which is the leading cause of hyperthyroidism. In this disease, antibodies that attack the thyroid gland cause its growth and hyperproduction of thyroid hormones (T3, T4). Some mothers may be concerned about the possibility of these antibodies passing into breast milk and potentially harming the baby, but this is not a problem. Thyroid autoantibodies are IgG immunoglobulins that are too large to pass into breast milk. Continued breastfeeding will only benefit your baby, as formula-fed babies themselves are at increased risk of autoimmune thyroid disease.

Can breastfeeding prevent some thyroid problems?

There is evidence that breastfeeding can help prevent thyroid problems in both mother and baby.