Tsa and baby food

Baby Formula | Transportation Security Administration

Carry On Bags: Yes (Special Instructions)

Checked Bags: Yes

Formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) in quantities greater than 3.4 ounces or 100 milliliters are allowed in carry-on baggage and do not need to fit within a quart-sized bag. Formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) are considered medically necessary liquids. This also applies to breast milk and formula cooling accessories, such as ice packs, freezer packs, and gel packs (regardless of presence of breast milk). Your child or infant does not need to be present or traveling with you to bring breast milk, formula and/or related supplies.

Inform the TSA officer at the beginning of the screening process that you are carrying formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) in excess of 3. 4 ounces. Remove these items from your carry-on bag to be screened separately from your other belongings. TSA officers may need to test the liquids for explosives or concealed prohibited items.

Although not required, to expedite the screening process, it is recommended that formula and breast milk be transported in clear, translucent bottles and not plastic bags or pouches. Liquids in plastic bags or pouches may not be able to be screened by Bottle Liquid Scanners, and you may be asked to open them (if feasible) for alternate screening such as Explosive Trace Detection and Vapor Analysis for the presence of liquid explosives. Screening will never include placing anything into the medically necessary liquid.

TSA X-ray machines do not adversely affect food or medicines. However, if you do not want the formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) to be X-rayed or opened, please inform the TSA officer. Additional steps will be taken to clear the liquid and you or the traveling guardian will undergo additional screening procedures, to include Advanced Imaging Technology screening and additional/enhanced screening of other carry-on property.

Ice packs, freezer packs, frozen gel packs and other accessories required to cool formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) – regardless of the presence of breast milk – are also allowed in carry-ons, along with liquid-filled teethers. If these items are partially frozen or slushy, they are subject to the same screening as described above.

Please see traveling with children for more information.

Travelers requiring special accommodations or concerned about the security screening process at the airport may request assistance by contacting TSA Cares online at http://www.tsa.gov/contact-center/form/cares or by phone at (855) 787-2227 or federal relay 711.

For more prohibited items, please go to the 'What Can I Bring?' page.

What Can I Bring? Food

Alcoholic beverages

- Carry On Bags: Yes (Less than or equal to 3.4oz/100 ml allowed)

- Checked Bags: Yes

Check with your airline before bringing any alcohol beverages on board. FAA regulations prohibit travelers from consuming alcohol on board an aircraft unless served by a flight attendant. Additionally, Flight Attendants are not permitted to serve a passenger who is intoxicated.

FAA regulations prohibit travelers from consuming alcohol on board an aircraft unless served by a flight attendant. Additionally, Flight Attendants are not permitted to serve a passenger who is intoxicated.

Alcoholic beverages with more than 24% but not more than 70% alcohol are limited in checked bags to 5 liters (1.3 gallons) per passenger and must be in unopened retail packaging. Alcoholic beverages with 24% alcohol or less are not subject to limitations in checked bags.

Mini bottles of alcohol in carry-on must be able to comfortably fit into a single quart-sized bag.

For more information, see FAA regulation: 49 CFR 175.10(a)(4).

Alcoholic beverages over 140 proof

- Carry On Bags: No

- Checked Bags: No

Alcoholic beverages with more than 70% alcohol (over 140 proof), including grain alcohol and 151 proof rum. For more information, see FAA regulation: 49 CFR 175.10(a)(4).

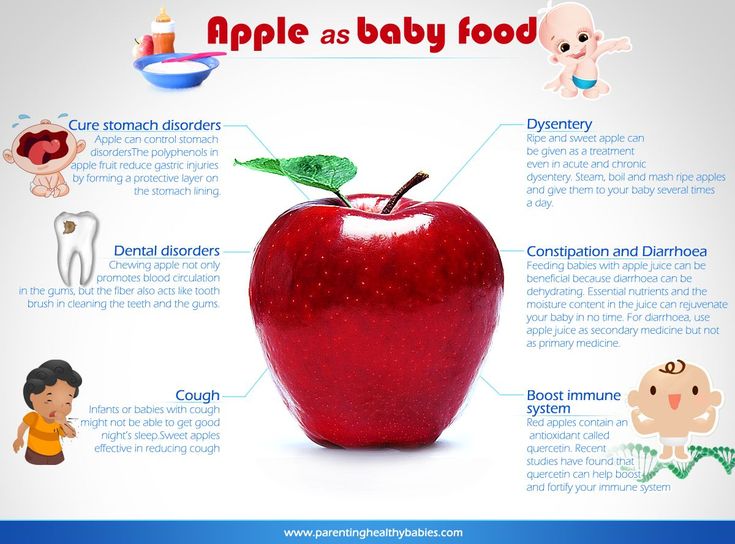

Baby Food

- Carry On Bags: Yes

- Checked Bags: Yes

Baby food is allowed in reasonable quantities in carry-on bags. Remove these items from your carry-on bag to be screened separately from the rest of your belongings. Please see traveling with children for more information.

Remove these items from your carry-on bag to be screened separately from the rest of your belongings. Please see traveling with children for more information.

Baby Formula

- Carry On Bags: Yes (Special Instructions)

- Checked Bags: Yes

Formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) in quantities greater than 3.4 ounces or 100 milliliters are allowed in carry-on baggage and do not need to fit within a quart-sized bag. Formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) are considered medically necessary liquids. This also applies to breast milk and formula cooling accessories, such as ice packs, freezer packs, and gel packs (regardless of presence of breast milk). Your child or infant does not need to be present or traveling with you to bring breast milk, formula and/or related supplies.

Inform the TSA officer at the beginning of the screening process that you are carrying formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) in excess of 3. 4 ounces. Remove these items from your carry-on bag to be screened separately from your other belongings. TSA officers may need to test the liquids for explosives or concealed prohibited items.

4 ounces. Remove these items from your carry-on bag to be screened separately from your other belongings. TSA officers may need to test the liquids for explosives or concealed prohibited items.

Although not required, to expedite the screening process, it is recommended that formula and breast milk be transported in clear, translucent bottles and not plastic bags or pouches. Liquids in plastic bags or pouches may not be able to be screened by Bottle Liquid Scanners, and you may be asked to open them (if feasible) for alternate screening such as Explosive Trace Detection and Vapor Analysis for the presence of liquid explosives. Screening will never include placing anything into the medically necessary liquid.

TSA X-ray machines do not adversely affect food or medicines. However, if you do not want the formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) to be X-rayed or opened, please inform the TSA officer. Additional steps will be taken to clear the liquid and you or the traveling guardian will undergo additional screening procedures, to include Advanced Imaging Technology screening and additional/enhanced screening of other carry-on property.

Ice packs, freezer packs, frozen gel packs and other accessories required to cool formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) – regardless of the presence of breast milk – are also allowed in carry-ons, along with liquid-filled teethers. If these items are partially frozen or slushy, they are subject to the same screening as described above.

Please see traveling with children for more information.

Travelers requiring special accommodations or concerned about the security screening process at the airport may request assistance by contacting TSA Cares online at http://www.tsa.gov/contact-center/form/cares or by phone at (855) 787-2227 or federal relay 711.

Bottled Water

- Carry On Bags: Yes (Less than or equal to 3.4oz/100 ml allowed)

- Checked Bags: Yes

Bread

- Carry On Bags: Yes

- Checked Bags: Yes

Solid food items (not liquids or gels) can be transported in either your carry-on or checked bags. Liquid or gel food items larger than 3.4 oz are not allowed in carry-on bags and should be placed in your checked bags if possible.

Liquid or gel food items larger than 3.4 oz are not allowed in carry-on bags and should be placed in your checked bags if possible.

TSA officers may instruct travelers to separate items from carry-on bags such as foods, powders, and any materials that can clutter bags and obstruct clear images on the X-ray machine. Travelers are encouraged to organize their carry-on bags and keep them uncluttered to ease the screening process and keep the lines moving.

Breast Milk

- Carry On Bags: Yes (Special Instructions)

- Checked Bags: Yes

Formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) in quantities greater than 3.4 ounces or 100 milliliters are allowed in carry-on baggage and do not need to fit within a quart-sized bag. Formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) are considered medically necessary liquids. This also applies to breast milk and formula cooling accessories, such as ice packs, freezer packs, and gel packs (regardless of presence of breast milk). Your child or infant does not need to be present or traveling with you to bring breast milk, formula and/or related supplies.

Your child or infant does not need to be present or traveling with you to bring breast milk, formula and/or related supplies.

Inform the TSA officer at the beginning of the screening process that you are carrying formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) in excess of 3.4 ounces. Remove these items from your carry-on bag to be screened separately from your other belongings. TSA officers may need to test the liquids for explosives or concealed prohibited items.

Although not required, to expedite the screening process, it is recommended that formula and breast milk be transported in clear, translucent bottles and not plastic bags or pouches. Liquids in plastic bags or pouches may not be able to be screened by Bottle Liquid Scanners, and you may be asked to open them (if feasible) for alternate screening such as Explosive Trace Detection and Vapor Analysis for the presence of liquid explosives. Screening will never include placing anything into the medically necessary liquid.

TSA X-ray machines do not adversely affect food or medicines. However, if you do not want the formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) to be X-rayed or opened, please inform the TSA officer. Additional steps will be taken to clear the liquid and you or the traveling guardian will undergo additional screening procedures, to include Advanced Imaging Technology screening and additional/enhanced screening of other carry-on property.

Ice packs, freezer packs, frozen gel packs and other accessories required to cool formula, breast milk, toddler drinks, and baby/toddler food (to include puree pouches) – regardless of the presence of breast milk – are also allowed in carry-ons, along with liquid-filled teethers. If these items are partially frozen or slushy, they are subject to the same screening as described above.

Please see traveling with children for more information.

Travelers requiring special accommodations or concerned about the security screening process at the airport may request assistance by contacting TSA Cares online at http://www. tsa.gov/contact-center/form/cares or by phone at (855) 787-2227 or federal relay 711.

tsa.gov/contact-center/form/cares or by phone at (855) 787-2227 or federal relay 711.

Candy

- Carry On Bags: Yes

- Checked Bags: Yes

Solid food items (not liquids or gels) can be transported in either your carry-on or checked bags. Liquid or gel food items larger than 3.4 oz are not allowed in carry-on bags and should be placed in your checked bags if possible.

TSA officers may instruct travelers to separate items from carry-on bags such as foods, powders, and any materials that can clutter bags and obstruct clear images on the X-ray machine. Travelers are encouraged to organize their carry-on bags and keep them uncluttered to ease the screening process and keep the lines moving.

Canned Foods

- Carry On Bags: Yes (Special Instructions)

- Checked Bags: Yes

There are some items that are not on the prohibited items list, but because of how they appear on the X-ray, security concerns, or impact of the 3-1-1 rules for liquids, gels and aerosols, they could require additional screening that might result in the item not being allowed through the checkpoint. We suggest that you pack this item in your checked bag, ship it to your destination or leave it at home.

We suggest that you pack this item in your checked bag, ship it to your destination or leave it at home.

Cereal

- Carry On Bags: Yes

- Checked Bags: Yes

baby food ads discriminated against men and grandmothers

Analysts of the SlickJump platform received unexpected results, who, using Google's socio-demographic algorithms, analyzed the interest of the Internet audience in the topic of baby food. It turned out that manufacturers and advertising agencies often ignored a significant part of the potential buyers of mixtures, juices and purees - men.

The baby food market is now gradually shrinking due to the negative impact of the pandemic. Worst of all were milk formulas (-13.5%), instant drinks (-11.1%) and dry cereals (-9,5%).

Researchers note that the decline in sales is a consequence of the pandemic and subsequent quarantine measures that forced consumers to change the way children eat. In turn, SlickJump also notes errors in targeting baby food ads. Analysts have noticed that manufacturers and advertising agencies, quite often, when choosing a target audience, focus only on young mothers (from 25 to 34 years old), in fact, ignoring the interest in baby food from men in general and women over 45 years old.

In turn, SlickJump also notes errors in targeting baby food ads. Analysts have noticed that manufacturers and advertising agencies, quite often, when choosing a target audience, focus only on young mothers (from 25 to 34 years old), in fact, ignoring the interest in baby food from men in general and women over 45 years old.

But recent data indicate that the topic of baby food is of great interest to men as well. To test this, SlickJump used Google's socio-demographic tools to analyze data from tens of thousands of visitors to articles about baby food on RuNet. The gender of readers was determined in 76% of cases, and the proportion of men was 17.3%. Analysts drew attention to the fact that women aged 25-34 among readers - 44.4%, aged 35 to 45 years - 21.65%, and the remaining ~ 34% are outside the age range of the target audience. Thus, it can be argued that targeting baby food advertising solely on socio-demographic parameters can reduce the volume of available paying audience by more than 58%. Given the fall in demand for baby food, this figure can be called shocking.

Given the fall in demand for baby food, this figure can be called shocking.

Losses are made up of age restrictions of the target audience (34%), gender restrictions of the target audience (18%) and the technical limit of reliability for determining social parameters (24-28%).

It can be assumed that the target audience of baby food buyers does not include people over 45 years of age. This conclusion can be drawn on the basis of studies and surveys that guide manufacturers. Thus, the Eurasian Union of Scientists published the results of a study of consumer preferences when purchasing baby food. It turned out that the main target audience for advertising baby food is people aged 25-35 years (78%), another 11% - from 36 to 45 years. Thus, people over 45 years old practically do not fall into the target audience of baby food buyers.

The authors of the study note that the figures reflect the real advertising strategy in Runet by baby food manufacturers, retail chains and their advertising agencies.

And this strategy can be considered as discriminatory and ineffective, because a fairly large part of Internet users do not see the advertising offers of baby food manufacturers and sellers, and are less oriented when choosing this product on the Internet.

Share on social networks:

Nestlé for babies, or how to run the perfect third world marketing campaign

Baby food is an emotional topic. It is unlikely that anyone will deny that breast milk is the healthiest, cheapest and safest product for feeding babies. However, it is known that for various reasons, not all mothers are able to feed their children with their own milk. Medical contraindications, lack of education or the need to go to work forced women to look for an alternative to breastfeeding babies.

In 1867, Nestlé was the first to develop and market baby food for premature babies. Even then, it was recognized that breastfeeding is ideal for the baby, and artificial formula is suitable only when the mother has no other choice. However, the invention of Henry Nestle was a real salvation for premature babies who were unable to take any other food. Over time, Nestlé has become the world's largest manufacturer of powdered infant formula.

However, the invention of Henry Nestle was a real salvation for premature babies who were unable to take any other food. Over time, Nestlé has become the world's largest manufacturer of powdered infant formula.

Description of the problem

Baby food sales skyrocketed in the post-war years as a consequence of the so-called post-war baby boom. Since the late 1950s, however, a decline in the birth rate began, which could not but affect income from the sale of food. In desperation, turning their eyes to the developing countries of Africa, South America and the Far East, industrialists realized that with the development of new markets, a successful future awaited them.

In the second half of the 20th century, the sociocultural situation began to change in poor countries. Women, who provided a significant part of the family income, began to meet more and more often. In order not to lose their place, after the birth of a child, they sought to return to work as soon as possible.

Purpose

The forthcoming marketing campaign was intended to:

- to popularize artificial feeding;

- Convince the target audience that powdered formula is better for infant feeding than breastfeeding;

- to increase sales of Nestlé's powdered baby food formulas.

Target audience

breastfeeding mothers, physicians, medical staff in maternity wards, pharmacists, workers in courses for new mothers.

Period

The 1960s are our time.

Tools

ATL (radio, press, outdoor advertising), BTL (sampling, promotions, direct marketing), brainwashing, lobbying.

Solution

Direct consumer promotion of dry formulas for artificial feeding in the third world countries was very diverse. Nestlé chose radio, newspapers, magazines, billboards and loudspeaker vans as its main advertising media. Samples, bottles, nipples and measuring spoons were generously distributed.

So, what was the content of the campaign itself, and, accordingly, the advertising media?

• Marketing methods were designed to mislead poor and illiterate mothers into thinking that artificial feeding was preferable to natural feeding;

• Booklets ignored or did not highlight the benefits of breastfeeding;

• Advertisements portrayed breastfeeding as old-fashioned and uncomfortable;

• Gifts and trial samples were intended as a direct incentive to formula feed.

• Active advertising in hospitals implied that the product was approved by the health system.

The practice of free or subsidized supplies of artificial milk to hospitals and maternity wards has also been adopted. This encouraged artificial feeding of children, but disrupted the proper functioning of the mammary glands. The calculation was that when the mother left the hospital, she could not re-transfer to breastfeeding, respectively, became a regular customer of the company's products.

About two hundred women were employed by Nestlé as promotional personnel, so-called "milk nurses", who were registered with hospitals as nurses, diet nurses, or midwives. These "sisters" were uniformed sales associates who visited mothers and gave them food samples in an attempt to convince them of the benefits of artificial feeding.

In addition to direct consumers, the company's advertising efforts were directed at doctors and other medical personnel. This type of marketing involved discussing product quality and performance with paediatricians, nurses, and other maternity staff. Materials such as advertisements, charts, and free samples have been made available to doctors, hospitals, and free clinics. Doctors and other hospital staff were paid by the firm to travel to medical conferences.

Materials such as advertisements, charts, and free samples have been made available to doctors, hospitals, and free clinics. Doctors and other hospital staff were paid by the firm to travel to medical conferences.

Nestlé now distributes posters and brochures to the Gabon health care system to promote powdered formula, distributes a type of formula, "Cerelac", gives gifts to healthcare workers, and supports travel and conferences.

In India, the company became the only baby food advertiser in the Indian edition of Parenting magazine. In addition, in order to be able to advertise "Cerelac" in Indian pharmacies, Nestlé pays local pharmacists an average of Rs 200 per month. A similar practice is carried out by the company in countries such as Chile, Colombia, Zimbabwe.

Campaign results

Thanks to Nestlé's marketing and promotional methods, dry mixes as a product have gained a certain prestige. And what could be more natural than a mother's desire to give her baby all the best. Thus, the “positions” of breastfeeding were undermined. In 1951, approximately 80% of three-month-old babies in Singapore were breastfed. In 1971 - only 5%.

Thus, the “positions” of breastfeeding were undermined. In 1951, approximately 80% of three-month-old babies in Singapore were breastfed. In 1971 - only 5%.

By the mid-1970s, powdered infant formula was the third most advertised product in the Third World, after tobacco and soap. Sales of Nestlé baby food in poor countries have skyrocketed.

In 1978, the company's annual turnover amounted to 11 billion dollars, and 31% of total sales at that time were in the third world countries. By comparison, 46% were in Europe and 20% in North America. Approximately the same were the indicators for the segment of dry mixes for feeding infants.

It is not yet possible to sum up the final results of the massive campaign to promote powdered infant formula in the countries of the "third world", since the "program" has not yet ended.

Seriously, the results are...

According to the World Health Organization, 1.5 million children die every year from unsafe formula feeding (most of them in Third World countries). And this means that one baby dies from improper feeding in 30 seconds. For at least the first 6 months of life, infants are recommended to be fed exclusively with breast milk. Introduction to the diet of products other than breast milk in the first months of life increases the risk of various diseases.

And this means that one baby dies from improper feeding in 30 seconds. For at least the first 6 months of life, infants are recommended to be fed exclusively with breast milk. Introduction to the diet of products other than breast milk in the first months of life increases the risk of various diseases.

It was not until the early 1970s that the first suspicions began to arise among the world community that baby food manufacturers, by vigorously promoting their product to Third World countries, contributed to a high percentage of infant mortality. Most of the end users were simply unable to read the manual due to the high illiteracy rate in those countries. In addition, Nestlé printed product instructions only in English prior to the relevant legislation.

Many consumers have been unable to use the product correctly due to living conditions, mixing food with dirty water or pouring the mixture into unsterilized bottles. Yet, according to UNICEF, an unhygienic artificially fed infant is at least 6 times more likely to die from diarrhea and 4 times more likely to die from pneumonia than a breastfed infant.

Equally problematic was that baby food was too expensive and many customers diluted it to useless levels. Accordingly, the baby's nutrition was inadequate.

New mothers were not informed that all the essential nutrients and antibodies found in mother's milk are almost entirely absent from dry formulas. Criticism was based on the fact that the company did not warn mothers about the possibility of artificial feeding only in emergency cases (for example, if a woman had to go to work soon, or if she was physiologically unable to breastfeed).

Nestle boycott

B 19'74 British charity War on Want publishes a 28-page document entitled "Babykiller" that publicly criticizes the marketing methods used by the Swiss company Nestlé in Africa for the first time. A year later, the German Third World Working Group accused Nestlé of "unethical and immoral behavior" in its article "Nestlé kills babies".

In 1977 two public interest groups, the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility and the Infant Formula Action Coalition (INFACT), announce a worldwide boycott of Nestlé. The movement soon gains support from over 450 local and religious groups across America, with supporters claiming it is the largest non-union boycott in United States history.

The movement soon gains support from over 450 local and religious groups across America, with supporters claiming it is the largest non-union boycott in United States history.

It was the worldwide boycott of Nestlé that led to the adoption in 1981 of the WHO International Code for the Marketing of Formula Feeding. Under the Code, baby food companies must not:

• Supply infant formula to hospitals;

• Advertise your products to community or health professionals;

• Use pictures of babies on baby food labels;

• Give gifts to mothers or health workers;

• Give free product samples to parents;

• Advertise meals for children under 6 months of age.

Baby food labels must be in a language the mother understands and contain an important warning about the contraindications and consequences of formula feeding.

New concept

However, as you probably already understood, Nestlé only declaratively supported the Code. In practice, the company tries in every possible way to circumvent its regulations. The company developed the concept that infant formula saves lives, not takes them - a hint that those children who cannot be breastfed for various reasons are no longer doomed to die. The problem is that Nestlé did not present this idea in a clear and understandable form in the early stages of the crisis. On the other hand, despite the new concept, the company's violations of various ethical and legal norms continue.

The company developed the concept that infant formula saves lives, not takes them - a hint that those children who cannot be breastfed for various reasons are no longer doomed to die. The problem is that Nestlé did not present this idea in a clear and understandable form in the early stages of the crisis. On the other hand, despite the new concept, the company's violations of various ethical and legal norms continue.

It wasn't until the early 1990s that Nestlé began to communicate with its stakeholders much more intelligently. A significant number of materials have been published, refuting the accusations against the company and restoring the truth as it is seen by the company. In essence, these were elements of a defensive strategy that left control of the problem at the mercy of groups of social activists who were aggressively disposed against the TNC itself. Partly to repair a damaged reputation, Nestlé launched a new marketing strategy in 2002 called Good Food. Good Life, which focuses on the health of consumers.

A similar story can be told about almost any transnational corporation in the world. And for Nestlé, she is not the only one. And this company, frankly, was simply unlucky, but it is not surprising that Nestlé, which controls half of the baby food market, was the first to be boycotted. Later, other baby food manufacturers were blacklisted by consumer advocacy groups for violating the Code and being subject to boycotts of their products: Abbott Ross, Mead Johnson, and Danone.

This is the world we live in. In it, all means are good to achieve the goal and to make a profit. You can take it easy, live with it. And you can choose a different path.

In 2005, three years after Nestlé had positioned itself as a health food manufacturer, research company GMI conducted a survey of 15,500 people in 17 countries about the image of leading multinational corporations. Nestlé has been voted the most boycotted company in the world. For example, 21% of the French and 36% of the Italians declared their rejection of Nestlé.