What do carolina wrens feed their babies

What Do Carolina Wrens Eat? (Complete Guide)

What seeds do Carolina Wrens eat?

What fruit do Carolina Wrens eat?

What do baby Carolina Wrens eat?

Where Do Carolina Wrens Feed?

How Does Winter Pose a Problem for Carolina Wrens?

What do Carolina Wrens eat in winter?

How can you help Carolina Wrens survive the winter?

Do Carolina Wrens eat from feeders?

What do you feed Carolina Wrens?

Do Carolina Wrens eat mealworms?

Other Feeding Tips

Interesting Facts About Carolina Wrens

The Carolina Wren (Thryothorus ludovicianus) has traditionally been considered a southern bird, but in the last century, it has expanded its habitat northward (in some instances are far north as Canada), presumably due to global warming. This northward movement does bring with it some challenges.

Because the Carolina Wren does not migrate and remains in its established habitat all year, it must be prepared to survive the harsher winters as it expands into cooler climates. While they are physically able to withstand the colder temperatures as long as they can find adequate food, maintaining, a suitable food supply can be a problem.

So, let's get into it; what do Carolina Wrens eat?

The Carolina Wren's diet consists mostly of insects, spiders and small vertebrates such as frogs, lizards and snakes. It also eats seeds, nuts, berries and other vegetable matter. Research conducted by Professor Beal in 1916 revealed that the Carolina Wren's diet consists of roughly 94 percent animal matter and 6 percent vegetable matter.

Interestingly, those percentages change according to the season. During the summer months, the Carolina Wren's diet consists of a mere 1 percent plant material and rises to 11 percent in the winter.

Carolina Wren with an insect in its beak

Common Sources of Animal Matter in the Carolina Wren's Diet:

- Spiders, including Daddy Longlegs, an apparent delicacy for the Carolina Wren.

- Caterpillars and Moths

- Beetles, including bean leaf beetles and cucumber beetles.

- Ants

- Bees and Wasps

- Grasshoppers and Crickets

- Leaf Hoppers, Cinch Bugs and Soldier Bugs

- Snails

- Tree Frogs

- Lizards

- Snakes

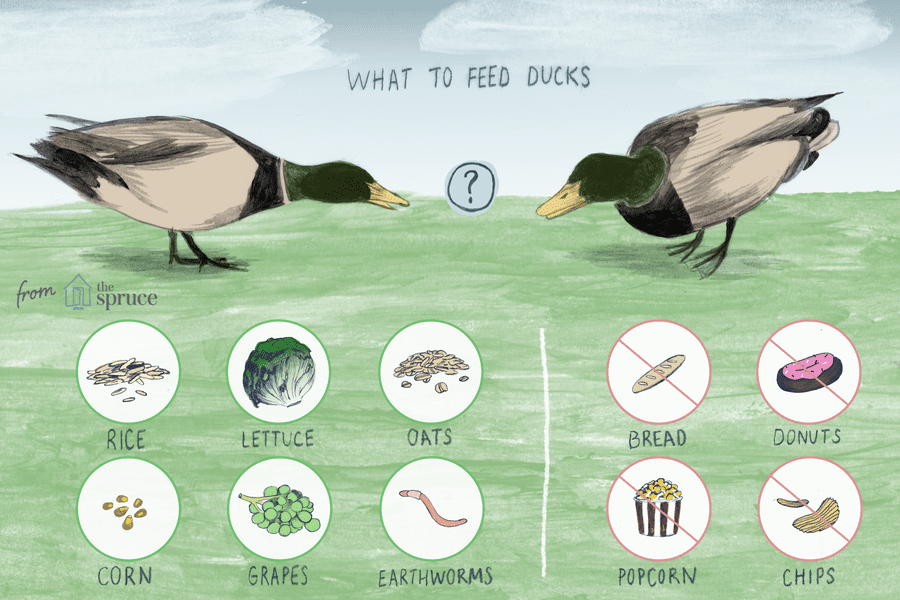

Common Sources of Vegetable Matter in the Carolina Wren's Diet:

- Acorns

- Bayberry Seeds

- Poison Ivy Seeds

- Sumac Seeds

- Fruit or Berries

- Weed Seeds

What seeds do Carolina Wrens eat?

Carolina Wrens eat seeds from native weeds and flowers, which varies depending on your location and the availability of seeds. They are known to eat bayberry, poison ivy and sumac seeds in the wild.

Carolina Wrens are reported to eat sunflower seeds and may eat other seeds in wild bird seed mixes if it is offered in the winter in feeders and their preferred food is not available.

Carolina Wren eating seeds

What fruit do Carolina Wrens eat?

Carolina Wrens eat bits of soft fruits native to the area they live in. They also eat a variety of soft berries.

They also eat a variety of soft berries.

What do baby Carolina Wrens eat?

Both the male and female Carolina Wrens share the duty of bringing food to the hatchlings. This typically consists of small bits of insects, spiders and other bugs. As the babies grow, they bring them larger portions and may bring grasshopper, crickets or caterpillars to the nest.

When the fledglings leave the nest, they typically follow their parents for a few days at which time the parents continue to feed the baby birds until they are ready to fend for themselves.

Where Do Carolina Wrens Feed?

Carolina Wrens can be found foraging for food in brushy areas, under trees, on the forest floor and in thorny bushes with dense foliage. They are primarily ground feeders and spend their time hopping from place to place and rummaging through leaf litter with their curved beak to uncover bugs and insects. They also feed in or around old bark on trees, fallen logs and brush piles where they likely seek out spiders and insects.

Carolina Wren foraging in the grass

How Does Winter Pose a Problem for Carolina Wrens?

Carolina Wrens expend a lot of energy with their constant motion and high metabolic rate, which means they need a constant and dependable food supply just to maintain their body temperature and keep from succumbing to the cold.

In the winter, especially when there is snow on the ground, they may not be able to find enough food on their own to sustain themselves. Many spiders and insects die, small vertebrates go into hibernation, and vegetation may be sparse. This all adds stress to the life of a Carolina Wren and maybe more than they can handle on their own. During cold spells, the mortality rate is high.

What do Carolina Wrens eat in winter?

In the Winter, Carolina Wrens forage for available food, such as old berries and fruit. They also take advantage of old seed heads and nuts, such as acorns. The food supply is often limited during the winter months.

Carolina Wren searching for food in the winter

How can you help Carolina Wrens survive the winter?

Providing a reliable and steady food source for Carolina Wrens increases their winter survival rates. Although there is evidence that the Carolina Wren can, and does, adapt to new food sources, the best way to help out is to provide foods they are known to consume.

Do Carolina Wrens eat from feeders?

Carolina Wrens may visit backyard feeders, especially platform feeders, but they are most comfortable feeding on or near the ground.

If Carolina Wrens shy away from your existing feeders, consider spreading seeds and nuts of the ground under the feeders. Likewise, try hanging suet feeders near shrubs and thorny bushes where the Carolina Wren feels most comfortable.

Carolina Wrens feeding from a bird feeder

What do you feed Carolina Wrens?

Try to vary the food you provide for Carolina Wrens, as some may prefer one food source over another. Here are some good choices:

Here are some good choices:

- Sunflower Seeds: The Carolina Wren is reported to eat sunflower seeds, but the best bet is to provide them with sunflower kernels or sunflower hearts as these are a convenient size for the Carolina Wren to eat.

- Suet: Look for High energy suet that contains both fat and protein. There are many varieties to choose from, from suet filled with fruits and nuts to those flavored with peanut butter or other enticing flavors. Observe the feeders closely to determine which kind of suet your Carolina Wrens prefer.

- Dried Nuts and Berries: Try an assortment of dried nuts and berries found in songbird seed blends.

- Peanuts: Carolina Wrens typically love shelled peanuts or peanut hearts. These are packed with protein and fats to give them the energy they need. At least one source claims one peanut provides one-third of a Carolina Wren's metabolic need for an entire day.

Do Carolina Wrens eat mealworms?

Carolina Wrens love mealworms and will devour them with a passion. Offering them mealworms at the bird feeder or in a shallow bowl near the ground or near shrubs where they frequent provides them with a good source of protein in the winter.

Offering them mealworms at the bird feeder or in a shallow bowl near the ground or near shrubs where they frequent provides them with a good source of protein in the winter.

If your Carolina Wrens are not eating the mealworms you provide, try soaking dried mealworms in warm water before offering them to your Carolina Wrens.

Carolina Wren with worm in beak

Other Feeding Tips

Because there are seven subspecies of the Carolina Wren, not every Carolina Wren will have the same food preferences or feeding habits. Each subspecies may make food and behavioral adaptations to suit the area it calls home. This makes it important to explore the feeding preferences of the Carolina Wrens in your area to find what works best for you.

All birds need water to survive and may find it difficult to find in the winter. Providing a heated birdbath is an excellent way to provide your Carolina Wrens with a source of fresh, clean water in the winter.

Interesting Facts About Carolina Wrens

- The Carolina Wren is a mere 5.

5 inches from the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail, but it has an amazing 11-inch wingspan.

5 inches from the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail, but it has an amazing 11-inch wingspan. - The male and female Carolina Wren look alike. Their body is reddish-brown with orange-brown underparts.

- The Carolina Wren has a dark, slightly curved beak.

- It has a long tail that flicks up and down as it forages for food or flits among bushes.

- The Carolina Wren has black eyes and distinctive white eyebrow stripes.

- Its face and chin are white or light tan.

- The Carolina Wren has a life expectancy of 6 years.

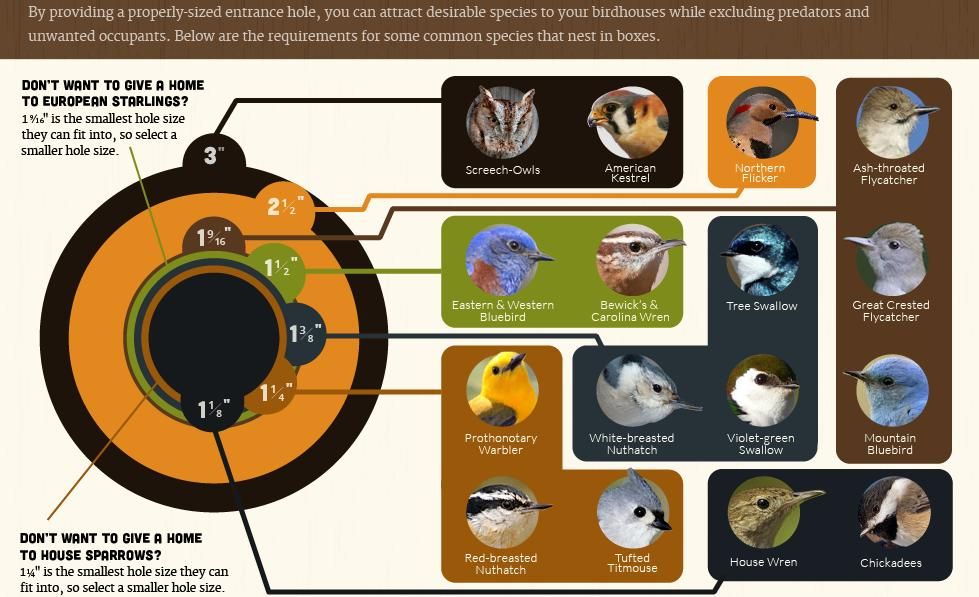

- Carolina Wrens may nest in old plant pots, in abandoned structures or in shrubs near the home.

- Carolina Wrens are territorial and are aggressive in defending their nests. The breeding pair may chase or peck predators or dive-bomb humans to protect their nests.

- Carolina Wrens are monogamous and remain with the same mate for several years.

Carolina Wrens can be seen flitting in shrubs and other small bushes or foraging for food under leaves and other litter under trees. They also hop up and down the trunks of trees, searching for insects under the bark or in crevices. They frequent brush piles and often seek out nesting spots near or in abandoned buildings. Because they do not migrate, the same Carolina Wrens will likely remain in your backyard year-round.

They also hop up and down the trunks of trees, searching for insects under the bark or in crevices. They frequent brush piles and often seek out nesting spots near or in abandoned buildings. Because they do not migrate, the same Carolina Wrens will likely remain in your backyard year-round.

Expert Q + A

Ask a question

Do you have a question about this topic that we haven't answered? Submit it below, and one of our experts will answer as soon as they can.

What Do Baby Wrens Eat?

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

A Rare Blue-Colored WrenWrens are frequently encountered across North America. These birds construct their nests in a variety of unusual locations, including old boxes, discarded cans, and even within barns and garages. It’s not uncommon for humans to discover abandoned wren babies or youngsters who’ve fallen from the canopy. It’s difficult to care for a wild wren, but with the right tools and understanding of how it works, it becomes much easier.

If the baby wren is uninjured, return it to the nest. If you can’t find the nest, wrap some newspaper around a berry basket and conceal it among dense bushes. Take any injured bird to your local veterinarian or a wildlife conservation organization if possible. If the parents are not contacted for three hours after the bird is returned to the nest, assume they have abandoned it and take it to a veterinarian, an animal shelter, or an indoor facility where you can care for it.

Caring for a baby wren requires effort and consistency. In this article, we explain how you can help a baby wren in an effective manner.

What Do Baby Wrens Eat? Baby Wrens Eat GrasshoppersThe diet of a baby wren is exclusively small terrestrial insects. The young and adults eat mostly spiders, bugs, and beetles while the youngsters still in the nest are fed mostly grasshoppers, caterpillars, and crickets. Adult wrens will feed their young, as well as supplement their own diet, with mollusk shells.

Wrens eat a wide variety of foods, most of which are high in protein. If they’re unable to find any bugs nearby, Wrens will resort to consuming insects. If insects aren’t found either, then their alternative option will be to feed on berries. Mealworms, peanuts hearts, peanuts, suet, and occasionally snail shells are all used to provide digestive grit in baby wrens. Digestive grit refers to the grinding of food in their stomach, which is aided by the presence of larger particles. You may attract a house Wren to your yard by putting some peanut butter on a stump or hanging a suet feeder. Wrens are an important part of your yard. They can consume all of the bugs and they’re fascinating to watch. The House Wren eats berries and insects, making it an omnivore.

Beetles Are Consumed By Baby WrensWarmth is important for baby wrens, especially if they’re abandoned in the wild. Line a shoebox with newspaper or paper towels and fill it with hot water. Small holes should be cut in the box’s lid and the baby bird should be placed inside. Keep the box hidden from children and pets by keeping it covered and away from them. Use a desk lamp with a high-wattage incandescent bulb to provide warmth. Fluorescent lights, on the other hand, do not give enough heat.

Keep the box hidden from children and pets by keeping it covered and away from them. Use a desk lamp with a high-wattage incandescent bulb to provide warmth. Fluorescent lights, on the other hand, do not give enough heat.

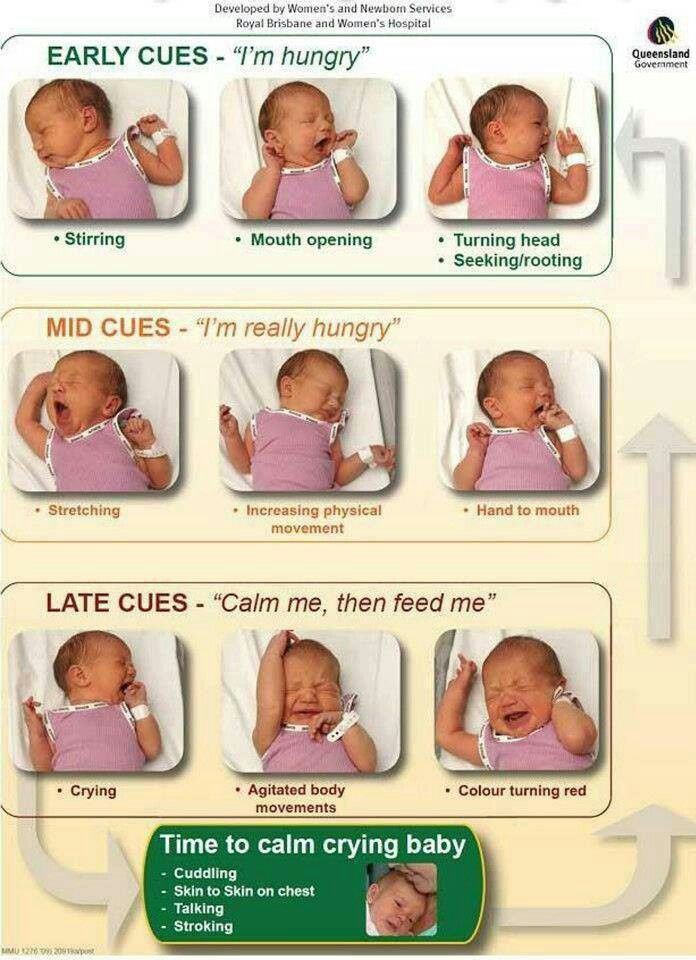

Baby wrens should be fed on a regular basis. Baby birds require food every 15 to 20 minutes when the sun is shining. To create a thick liquid, combine one part protein, such as canned puppy pup food or dried beef baby food, with two parts high-protein baby cereal or powdered grain meal. Feed the infant via a syringe or eyedropper.

Baby Wrens Eat SpidersNow it’s time to teach the baby wren how to eat insects. Offer tiny crawling insects, such as mealworms, at each feeding when your youngster is younger. To encourage a feeding response, press an insect against the beak of the baby wren. Because feeding is natural, don’t worry if it takes some practice.

Peanuts Are Also A Part of a Baby Wren’s DietReplace the container with a larger box as the bird matures. Old birds will become claustrophobic in a shoebox and require more space. Take the pet outside in a cage or box on occasion to acclimate it to the outdoors. Do not allow the baby wren to fly about freely in its habitat.

Old birds will become claustrophobic in a shoebox and require more space. Take the pet outside in a cage or box on occasion to acclimate it to the outdoors. Do not allow the baby wren to fly about freely in its habitat.

Once the baby wren is released, turn on some music and start dancing. Place the cage or box in an outdoor space that you’re familiar with where no dogs or cats are allowed to roam. Leave the lid or door open, and watch the bird fly off on its own. Leave the wren in its cage for several weeks so it has time to get used to you, but don’t handle or talk to it. The wren will revert to being wild at some point.

How Much Do Baby Wrens Eat?Feed the baby wren every 15 to 20 minutes throughout the day. Soak the kibble in water until it is soft and pliable. Dry out the water before mixing in a kibble and baby cereal with a ratio of 1:2. This will create a fluid mixture. It must be a liquid state. Fill the dropper or syringe and press the food into the bird. Make sure the food does not end up under its tongue if you’re feeding a fledgling nestling since this might obstruct its airway.

Make sure the food does not end up under its tongue if you’re feeding a fledgling nestling since this might obstruct its airway.

Place newspaper on the shoe box and line it up. Place the baby bird inside and punch holes in the top of the shoe box. Cover the shoebox with the lid and shine the lamp on it. Turn on (insert the light bulb and turn it on).

Can Baby Wrens Be Kept As Pets?No, house wrens are not a good choice as pets. These little birds may be aesthetically appealing, but they do not function well in a living environment. These are wild birds that require ample area to fly and explore. It is illegal to keep one as a pet in most areas.

It is against the law to keep wild birds, and they must be released as soon as feasible. It’s critical that little human interaction occurs so that the bird does not become domesticated. When a wild bird is discovered, it is HIGHLY advised to turn it over to the proper authorities.

Put your finger in the baby bird’s feet to determine whether it is a nestling or a fledgling. A fledgling has a firm grip on your finger if it does. It is a nestling if there is no hold on your finger at all. Watch the birds‘ nest for two hours after you put the wren back in. Assume that the parents have died if there is no parental care and contact your local wildlife conservation. It’s a myth that parent birds would abandon their young if they come into touch with humans.

A fledgling has a firm grip on your finger if it does. It is a nestling if there is no hold on your finger at all. Watch the birds‘ nest for two hours after you put the wren back in. Assume that the parents have died if there is no parental care and contact your local wildlife conservation. It’s a myth that parent birds would abandon their young if they come into touch with humans.

The top portion of a wren is reddish-brown and has fine darker brown bars on the wings, tail, and rump. The lower sides are pale brown with numerous, heavier streaks across the shoulders and abdomen. They have a short chestnut-hued tail with dark brown streaked sides.

The crown of a wren is browner, with fewer streaks and a pale supercilium from the bill’s base to just beyond the eye. They have long, thin bills that are slightly downcurved and black on top, with yellow on the bottom. The eyes of wrens are dark brown, and their feet and legs are pale browns in color. Male and female wrens appear identical.

Male and female wrens appear identical.

The House Wren is tiny yet has a loud voice. This creature makes chatters, rattles, and scolds when it detects potential predators. The house wren is a mundane little brown bird whose plumage varies by gender. Because of the sound it creates, you may identify a House Wren if it’s male or female.

Another indication that you’re looking at a wren is because it has white dots on its back. The wrens have evolved to blend in with their surroundings, which aids them in hiding from predators while still feeding on food. The House Wren weighs approximately half an ounce. That’s the size of half of a slice of whole-wheat bread, which is about five to six inches long. They live for up to nine years. They are typically around four to five inches long. The House Wren’s wingspan is approximately 6 inches. The House Wren flies near to the ground in its airborne method of transport. They are bright and lively, just like their music. However, they may be rather territorial.

The head, nape, and neck of baby wrens are crimson with streaks, while the underparts are streaked with black.

What Are The Natural Predators of Baby Wrens?The Wren is vulnerable to a variety of predators, including cats, opossums, rats, and woodpeckers. The female will lay one egg each day until five or six eggs are laid after choosing and constructing the nest.

At 12 to 15 days, the nestlings remain in the nest for 12 to 15 days. The mother leaves the nest periodically to obtain food while she is incubating. The period of time when the baby remains in his or her parent’s nest is known as incubation.

House Wrens’ songs are very strident, as they are produced in periods of time. They frequently do so during the breeding season to bring in additional mates. The House Wren leaves for warmer climes during the winter, but the trip is hazardous. The Wrens live in the southern United States, and they are among the most distinctive birds. Because of how harsh winter is, only half survive. The House Wren is a fantastic creature with an amazing song.

The House Wren is a fantastic creature with an amazing song.

The house wren is a tiny bird that commonly flies and nests low to the ground, thus it is consumed by a variety of predators. Rats, opossums, foxes, squirrels, raccoons, owls, kites, and snakes are among the many creatures that may be found in any environment. Woodpeckers, like wrens, can also take revenge on tiny birds for stealing their eggs. The pugnacious little songbird, on the other hand, does not shy away from attacking predators with its sharp beaks and claws.

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc, or its affiliates.

A rare video showing how whales feed their cubs

Breaking news

"Secret mechanisms of nature" - for the first time on the Nauka TV channel

"Secret mechanisms of nature" - for the first time on the Nauka TV channel

Scientists filmed a rare video of female humpback whales feeding their babies with milk

Using special cameras and drones, scientists filmed a rare video of female humpback whales feeding their babies with milk. It is reported by portal ScienceAlert citing University of Hawaii website.

Whales are known to be mammals and feed their offspring with milk. It is very difficult to observe this process, since whales are very large animals that can move around the entire oceans. Thanks to cameras that were able to attach to the body of animals, scientists from the University of Hawaii, Stanford and California filmed how humpback whales feed their cubs.

Each year, female humpback whales give birth to their calves in the warm, shallow waters of the Hawaiian archipelago and for some time (January to March) nurse their cubs before their long migration to Alaska. The research team wanted to know how often and for how long baby whales feed in order to be strong enough for spring migration. Special cameras were attached to seven humpback whale calves using suction cups. The team also used drones to watch the whales from above. As scientists note, they managed to get unique and rare footage that allows them to study the process of feeding humpback whales. Experts hope that the findings will help to learn more about the life of these incredible animals.

Previously, the University of Hawaii filmed an unusual way of feeding humpback whales.

Photo: UH Mānoa Marine Mammal Research Program/NOAA

The site may use materials from Facebook and Instagram Internet resources owned by Meta Platforms Inc. , banned in the Russian Federation

, banned in the Russian Federation

Tell a friend

-

Found new evidence of life in the ocean moon of Saturn

-

Sugar: to refuse or not?

-

Shutterstock

Scientists explain why humans became upright

-

Manuscript fragment

Museum of the Bible

Found part of the lost oldest star catalog - 2000-year-old manuscript of Hipparchus

-

Visualization by B. MéNard & N. Shtarkman

13 billion years in a few mouse movements: the largest interactive map of the Universe has been published

Do you want to be aware of the latest developments in science?

Leave your email and subscribe to our newsletter

Your e-mail

By clicking on the "Subscribe" button, you agree to the processing of personal data

Profile

Spiders and cobwebs November 30, 2018, 17:57

-

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

-

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

-

Photo by Zhanqi Chen et al.

-

Photo by Science/AAAS.

-

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

-

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

-

Photo by Zhanqi Chen et al.

-

Photo by Science/AAAS.

It turned out that some female spiders feed their young with a nutrient liquid, which the authors of a recent work called milk. But scientists were surprised not so much by this as by the fact that the mother feeds offspring for quite a long time.

But scientists were surprised not so much by this as by the fact that the mother feeds offspring for quite a long time.

On a summer night in 2017, scientist Chen Zhanqi made a curious discovery in his laboratory in China's Yunnan province. He noticed on the belly of the mother a young jumping spider of the species Toxeus magnus (arthropods lived in an artificial nest). Such a scene reminded the researcher of young mammals sucking their mother's milk.

Further research by Chen and his colleague Quan Rui-Chang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences confirmed that female jumping spiders do produce nutrient fluid for their young. The authors of the work called it milk.

Mammals are known to take care of their offspring for a long time. Female animals feed their babies with milk (it took about two and a half years for an ancient person).

Photo by Rui-Chang Quan.

Such care, simultaneous milk feeding and long-term care, is an unheard-of generosity for the world of insects, arthropods and other invertebrates. At least that's what it used to be.

At least that's what it used to be.

The heroes of a recent study are female T. magnus laying between two and 36 eggs at a time. After the young are born, the mother begins to deposit tiny milk droplets around the nest, which Chen and his colleagues observed in the lab.

Spider milk surprised experts a lot. Arthropods provide food for their offspring in different ways: belching, unfertilized eggs, or, in extreme cases, their own flesh, but not milk ...

Experts analyzed the liquid. It turned out that it contains fats, sugars and proteins, the content of which is four times higher than in cow's milk.

What happens to the spider family next? In the first couple of days, the spiderlings ate droplets of milk, scientists write. Later, the young were fed with nutrient fluid directly from the mother's epigastric sulcus.

Photo by Zhanqi Chen et al.

On the 20th day, young arthropods began to hunt outside the nest, while they continued to supplement their diet with mother's milk. This continued until reaching puberty (after another 20 days).

This continued until reaching puberty (after another 20 days).

As scientists say, when the spiderlings grew up, the mother began to attack the males if they returned to the nest, but she treated the females more calmly. Perhaps this behavior helps prevent inbreeding.

When Chen tried to paint over the epigastric sulcus of the female spider to cut off the milk supply, all the spiders younger than 20 days old died.

If he removed the mother from the nest, the "teenager" spiders grew more slowly and left the nest early. In addition, they were more likely to die before reaching adulthood.

Scientists say that other species of spiders also stay close to their young for several days after birth, but they rarely feed them in this way.

Some amphibians and other invertebrates are known to lay similar trophic eggs to feed their young, the scientist notes. Although animals do this only when the cubs are still very small.

What is interesting in this study is not even that the spiders of the species T. magnus produce milk, but how long they feed it to their young.

magnus produce milk, but how long they feed it to their young.

Such long-term parental care (as in jumping spiders) occurs only in some long-lived social vertebrates: humans or elephants, for example, notes Rui-Chan.

According to him, the discovered example of maternal care indicates that invertebrates have also developed this feature.

According to behavioral ecologist Nick Royle of the University of Exeter, who was not involved in the study, the results help "improve understanding of the evolutionary origins of complex forms of parental care."

In his opinion, such care often signals greater than usual needs of offspring (for example, when there is a shortage of food for babies). In this case, it really makes sense for mothers to become especially caring parents.

Such behavior requires additional efforts and resources from females, and therefore it appears, most likely, only in extreme conditions.