What do wild birds feed their babies

What Do Baby Birds Eat? Feeding Tips & Dietary Needs

Spring is a busy time of the year for wild birds with breeding, nest-building, and raising babies in full swing. As soon as baby birds emerge from their shells, they’re completely dependent on their parents for everything. Because they’re so vulnerable, baby birds have no choice other than to rely on their parents for food. Newly hatched baby birds cannot break down food which means their parents must partially digest the food to make it safe for their young to eat.

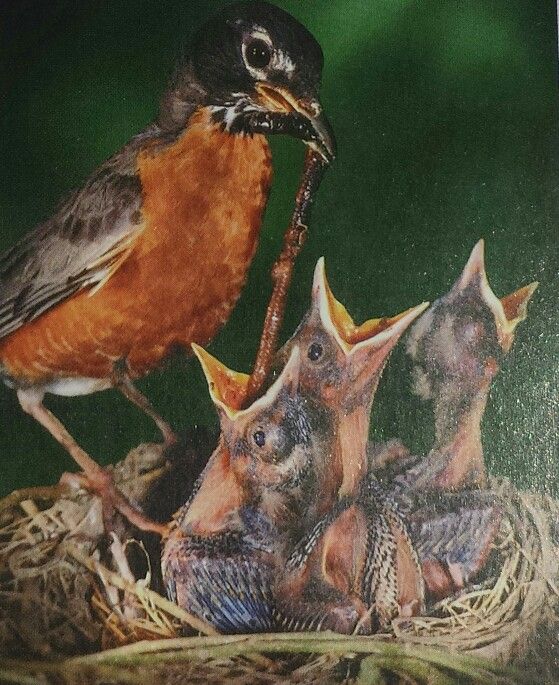

In the wild, baby birds eat the same food their parents eat which includes things like insects, seeds, and worms. When a bird parent hunts for food to feed its young, it will pick up an insect, worm, or seed, and eat the item. Upon returning to the nest, the bird will regurgitate what it just ate so as to soften the item before feeding it to its babies.

What to Feed a Wild Baby Bird

Image Credit: Gerhard G., PixabayIf you come across a baby bird in the wild that appears to be abandoned and in need of care, you may wonder what you should do. If possible, immediately contact a bird rescue organization near you to see what they advise. If this isn’t possible, you should do whatever you can to save the little bird.

An abandoned baby bird that can’t fly won’t survive long on the ground as it’s an easy target for a predator. If a predator like a cat, fox, or hawk doesn’t get the bird, it’s likely that it will die from dehydration or starvation. That’s why time is working against you when you find a baby bird that’s left on its own.

It’s possible that you can save the young bird by feeding it soft and spongy food that’s been soaked in water but not overly wet. But the first thing you should do is get that little bird up and off the ground. Carefully pick up the bird and place it in a box that’s lined with tissues, paper towel, or another soft material. If you can, take the bird to a quiet, safe location so you can feed it.

You can try to feed the baby bird things high in protein such as:

When you’ve got the food item on hand, it should be ground up and moistened slightly to make it easy for the bird to eat, swallow, and digest.

Keep in mind that professional bird rehabbers tube feed baby birds. If you have a food dropper, great! Otherwise, you can cut a small corner from a baggie and put the softened food into the bag and slowly squeeze a tiny bit of it into the baby bird’s mouth. Do not force the food onto the baby and be patient. With any luck, the baby bird will accept the food you’re offering it, to increase its chances of survival.

- Related Read: What Do Quails Eat in the Wild and as Pets?

Baby Birds Have Stringent Dietary Needs

Image Credit: PiqselsBaby birds are fed often by their parents. On average, they eat every 10 to 20 minutes for about 12-14 hours each day, depending on the species. The majority of their diet is made up of proteins which are primarily supplied by insects for healthy growth.

Even though it’s fine to try and save a baby bird by feeding it yourself, only a professional bird rehabber has the right food, equipment, supplements, and know-how to maintain such a stringent feeding regime. This means it would be best for that little bird to be taken to a bird rescue organization as soon as possible. A baby bird cannot live much longer than 24 hours without proper nutrition and care.

This means it would be best for that little bird to be taken to a bird rescue organization as soon as possible. A baby bird cannot live much longer than 24 hours without proper nutrition and care.

How to Tell if a Baby Bird is Orphaned

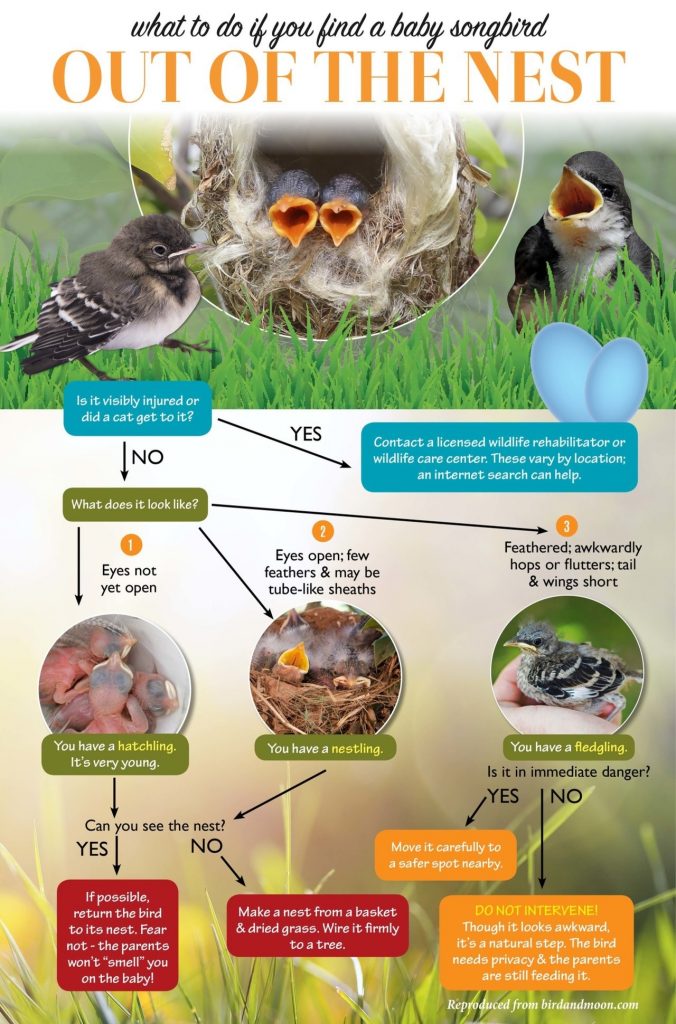

Image Credit: baby-bird_Vinson Tan, PixabayWhen you spot a young bird on the ground, your first response is probably to pick that bird up to help it. But before you take action and intervene, you should make sure that little bird actually needs your help.

A baby bird can be either a nestling or a fledgling, depending on its age. Most baby birds found on the ground are fledglings. These birds have recently left the nest, they can’t fly yet, and they’re under the watchful eye of their parents, and don’t need your help.

How to ID a Fledgling

Image Credit: Vinson Tan_PixabayA fledgling is feathered and capable of hopping and flitting, and can tightly grip your finger or twig. A fledgling is a fluffy and affordable looking young bird with a short tail. There’s no reason to intervene when you find a fledgling on the ground, unless you want to get the bird out of harm’s way.

There’s no reason to intervene when you find a fledgling on the ground, unless you want to get the bird out of harm’s way.

It’s fine to place a fledgling on a nearby branch to keep it away from pets like dogs or cats. But it won’t do any good to put a fledgling back in its nest because it will just hop out again.

It’s likely that this little bird’s parents are busy tending to other fledglings that are scattered around elsewhere. Before you know it, those parents will show up to tend to the fledgling you found.

How to ID a Nestling

Image Credit: Franck Barske, PixabayIf the baby bird has very few feathers and cannot hop, flit, or grip your finger tightly, it’s a nestling that somehow got out of the nest. If you can find the nest nearby, put the nestling back in as soon as possible. Don’t believe the old wives’ tale that says bird parents will abandon their baby if it’s touched by humans, because it’s simply not true.

If you can’t find the nest, have found both parents dead, or are absolutely sure the baby bird is an orphan, then you should step in and help. As mentioned earlier, the best person to care for the nestling you found is a professional bird rehabilitator.

As mentioned earlier, the best person to care for the nestling you found is a professional bird rehabilitator.

Conclusion

If you’ve ever wondered what baby birds eat, now you know—plus much more interesting information about our feathered friends in the wild.

Related Read: How to Take Care of a Lost Baby Bird (Care Sheet & Guide 2021)

Featured Image Credit: sonywiz, Pixabay

How Do Mother Birds Feed Their Babies? Birds Advice Guide

Mother birds always love their babies unconditionally. They spend a lot of time to take care of their babies and keep them safe as much as possible. Also, they don’t discriminate to their babies in terms of feeding them.

Then there is a question among bird lovers. How do mother birds feed their babies? The answer is that most mother birds eat food and then regurgitate it for the babies. They often feed their babies insects so that they can get more protein and grow healthy.

And that’s why we will provide you some necessary information so that you will be able to know how mother birds feed their babies. This writing is also our loving dedication to our beautiful feathered friends.

This writing is also our loving dedication to our beautiful feathered friends.

How Do Mother Birds Feed Their Babies?Handy Hint: To read more about birds food, visit our other article about What To Feed A Baby Bird Without Feathers? [here..], What Birds Eat Black Oil Sunflower Seeds? [here] and How To Feed Wild Birds? [here..]

Baby birds always depend on their parents to eat food. In this case, a mother bird usually digests the food and then puts that food into the babies’ mouth. The babies always open their mouth wide and screech for the food when they are hungry.

However, the feeding method may be different, depending on the species. But every time the baby bird, which screeches louder, usually gets more food than others.

If the baby bird gapes its mouth strongly, then the parent can feed it easily, and the baby will be able to swallow much larger items.

How Do Mother Birds Ensure Which One Needs More Food?Sometimes each baby bird doesn’t get an equal amount of food. Perhaps it may be sick or is unable to show the parent that it needs food.

Perhaps it may be sick or is unable to show the parent that it needs food.

In most cases, the other siblings are bigger and stronger. They can shove their other nestmates to get the food.

You may find various species of birds that have a variety of behaviors and sibling competition. So, it is tough to be sure entirely about birds.

Indeed, the mother bird has enough memory to know which one has immediately got food or even, which has not got the food for a while.

Besides, the one which is hungrier screech louder, and the mother usually put the food into the loudest screecher’s mouth.

Again, mother birds observe their babies well. The one which is swallowing silently, putting the food in the gullet, doesn’t get food in that particular time.

Most Mother Birds Provide Protein-Laden FoodEvery mother bird usually feeds their babies many different things depending on their species.

Some perching birds like sparrows and finches eat seeds, nuts, and berries. But they feed their young babies insects because young birds need more protein than are found in the adult’s diet.

But they feed their young babies insects because young birds need more protein than are found in the adult’s diet.

Songbirds often feed their babies almost 4 to 12 times an hour. They mostly provide the baby birds protein-laden insects and worms to make sure that they will be healthy.

Some Mother Birds Changes Food HabitSome parent birds that usually eat seeds, such as finches, cardinals, and sparrows, switch to insects during the breeding season.

Generally, the mothers eat the smaller insects themselves and take the larger ones back to the nest for the babies. So, they can carry more food to their ever-hungry offsprings.

Before feeding the babies, the parents hit the insect against the tree-branch or the ground. They kill the insect and soften the hard shell.

Sometimes, the parents chew the insect, and then break up the exoskeleton to make it edible for the baby birds.

Some Mother Birds Feed Substantial Milk to Their BabiesSome birds produce a substance similar to mammal milk. Pigeons are the best-known producers of crop milk, and both sexes produce it.

Pigeons are the best-known producers of crop milk, and both sexes produce it.

Crop milk produced by sloughing of special cells in the crop is very nutritious. Even pigeon milk has more fat and protein than that of cow or human.

For the first few days after hatching, crop milk is the only food that the mother bird provides to the baby birds.

Both parents feed crop milk for a couple of weeks. As the babies get older, it gets seeds with the milk. When they are gradually getting older, they get more seed rather than less milk.

Some Mother Birds Feed Their Babies DifferentlySome parents, such as pigeons and doves, feed their babies by using different styles and techniques. They usually squeak and tap their beak against the baby birds’ beak to feed the food. The babies stick their beak down the parent’s throat and suck up to food of the crop.

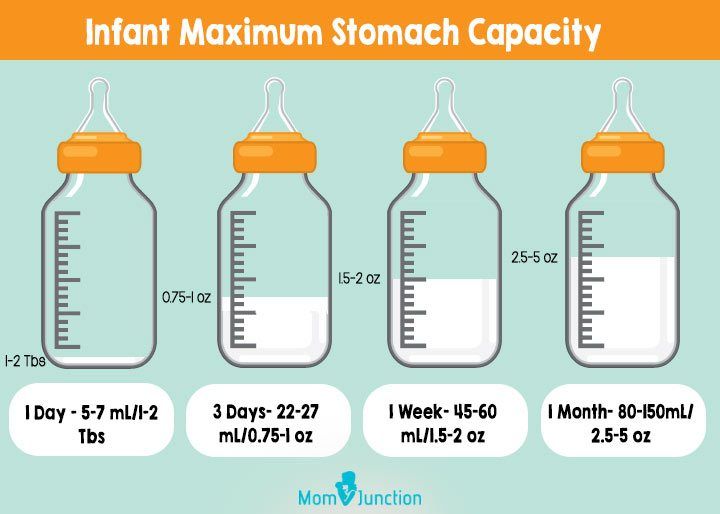

Most of the songbirds do not have an actual crop, which is essentially a sack capable of holding a large amount of food. The baby birds which don’t have a crop can only hold a small amount of food at a time. They must be fed almost every 20 minutes from sunrise to sunset.

The baby birds which don’t have a crop can only hold a small amount of food at a time. They must be fed almost every 20 minutes from sunrise to sunset.

On the other hand, pigeons and doves can hold a large amount of food, which passes slowly through the digestive system. Even the youngest baby pigeon or dove can be fed no more than every couple of hours.

Some Mother Birds Feed Their Babies at NightMost birds sleep and rest at night. But, some birds specialize at the nocturnal activities. Nocturnal birds are in the minority, but there are plenty of genus and species of nocturnal birds.

For example, most owls hunt at night and are inactive during the day. Also, nighthawks kill insects in flight at night.

Besides, some swifts kill airborne insects at night. Bitterns and night herons are nocturnal. But most night herons are not.

Final WordsHopefully, you are now well-known of the term “How do mother birds feed their babies?” As the baby birds entirely depend on their mother, they actually eat whatever their mother usually feeds.

When the baby birds are born, they are not able to eat food by themselves, so their mother, sometimes father, digests the food to make it safe for them. Then the parent puts the food into the mouths of its babies.

However, some birds have multiple eggs, but the only one who is the strongest and gets more food will survive each brood. Then, the particular bird will be the example of ‘survival of the fittest.’

Different ways of feeding the cubs of animals - the World of Knowledge

In some species of animals, parents immediately wean the cubs from themselves. Others feed their babies until they learn to feed on their own. In many animals, babies are completely weaned from their parents from the first minutes. Someone feeds the cubs until they can eat on their own. The offspring of mammals from the moment they are born until the transition to "adult" food sucks mother's milk.

Chicks and Broods

A warm May day on the Pacific coast of California. The reserve located here is filled with noise and screams. Many of the most diverse birds are busy with the main thing in this hot time - feeding the chicks. Shaggy chicks of the brown pelican stretch their necks here to get into the throat sac of their parents and profit from regurgitated fish. The chicks are only a few days old, their body is covered with sparse fluff, and for most of the day they huddle together without leaving the nest located on the ground.

The reserve located here is filled with noise and screams. Many of the most diverse birds are busy with the main thing in this hot time - feeding the chicks. Shaggy chicks of the brown pelican stretch their necks here to get into the throat sac of their parents and profit from regurgitated fish. The chicks are only a few days old, their body is covered with sparse fluff, and for most of the day they huddle together without leaving the nest located on the ground.

And not far away, a family of avocets—small waders with thin beaks curved upward—slowly stroll through the shallow water of a salt puddle. Fluffy chicks leave the nest immediately after hatching and paddle after their parents, foraging on their own. At first, the hunt is not very successful: the kids immerse their beaks in the water, as a rule, to no avail. But parents patiently help inexperienced kids, calling them to where there are more living creatures.

Pelicans, like many other birds, belong to the so-called chick species of birds: their babies are born blind and naked and at first remain in the nest. Their parents tirelessly feed them until the chicks fledge and begin to fly.

Their parents tirelessly feed them until the chicks fledge and begin to fly.

Avocets are brood birds. Their chicks hatch well developed. They soon leave the nest and begin to forage on their own.

On a milk diet

Feeding young with milk is a characteristic feature of all mammals. When an embryo forms in the female's uterus, under the influence of the sex hormones estrogen and progesterone, her mammary glands begin to increase in size, preparing to provide nutrition for the cubs.

The mammary glands are made up of cells that produce milk. It flows into special ducts that open at the tip of the nipple. The mammary glands begin to produce milk only after the birth of the baby. At this time, the level of estrogen and progesterone in the mother's blood drops sharply, but the content of prolactin increases, which stimulates the secretion of milk. Feeding babies with milk leads to increased production of prolactin and the release of another hormone, oxytocin, which helps the muscles of the mammary glands contract and expel milk from the nipples. When the cubs switch to another food, the female's milk production stops, and her mammary glands again decrease in size.

When the cubs switch to another food, the female's milk production stops, and her mammary glands again decrease in size.

Baby cetaceans do not have lips, so they cannot suckle. But the female has very strong muscles around the nipple, which, contracting, inject a powerful stream of milk directly into the cub's mouth. Due to this, the nutrient liquid is almost not diluted with water.

Milk composition

Milk is very nutritious. It consists of water, proteins (including easily digestible casein), carbohydrates and fats. The ratio of these ingredients depends on the environmental conditions and the needs of the cub. Usually, the more carbohydrates in milk, the less proteins and fats. Mammals living in arid places (deserts or savannahs) have much more water in their milk than European grasslands. The offspring of marine mammals and animals of cold latitudes receive very fatty milk.

Energy-rich fat is the best fuel for keeping animals warm. Newborn babies of mammals that inhabit the cold seas and subpolar regions of the land must grow especially quickly in order to quickly learn to withstand the harsh climate on their own. Therefore, they have a great need for high-calorie nutrition, and it can only be satisfied with fat milk.

Newborn babies of mammals that inhabit the cold seas and subpolar regions of the land must grow especially quickly in order to quickly learn to withstand the harsh climate on their own. Therefore, they have a great need for high-calorie nutrition, and it can only be satisfied with fat milk.

Milk nutrition is the most initial stage in the development of newborns. When it ends, the cubs must get their own food. Herbivorous mammals usually learn this on their own: their feeding does not require special skills. But for predators, the ability to get food is a whole science. At first, parents mainly feed the cubs with regurgitated and chewed pieces of their prey. Then hunting lessons begin.

Bird's milk

Pigeon chicks could not survive without "pigeon milk" - a viscous whitish substance, a bit like cottage cheese, which is secreted by cells located in the walls of the crop in adult birds. In its composition, it is close to the milk of mammals and is also produced thanks to the hormone prolactin. Under the action of prolactin, the cells in the goiter of the pigeon are filled with "milk" and separated from the walls of the goiter, and the chicks take them out, thrusting their heads deep into the beak of their parents.

Under the action of prolactin, the cells in the goiter of the pigeon are filled with "milk" and separated from the walls of the goiter, and the chicks take them out, thrusting their heads deep into the beak of their parents.

Pink flamingos also feed their chicks with a special milk. It contains not only semi-digested crustaceans and algae, but also special secretions of the esophagus containing a significant amount of blood from an adult bird, so the “milk” is colored pink. In terms of nutritional value, this liquid is not inferior to the milk of mammals.

Flamingo chicks feed on "milk" during the first two months of life. During this period, their beak, straight from birth, begins to slowly bend down, and when it becomes as hunchbacked as that of their parents, the babies begin to feed on their own.

Eaten alive

Some animals parasitic feed their young. Relatives of wasps, ichneumons, sit "on horseback" (hence their name) on caterpillars and other insect larvae and lay eggs in the victim's body. The ichneumon larva develops inside the caterpillar, eating it alive. When the caterpillar pupates, the rider larva also pupates inside it. As a result, not a butterfly is born from a chrysalis, but a rider. Some species of ichneumons develop inside the larvae of other ichneumons, which in turn develop in the body of caterpillars!

The ichneumon larva develops inside the caterpillar, eating it alive. When the caterpillar pupates, the rider larva also pupates inside it. As a result, not a butterfly is born from a chrysalis, but a rider. Some species of ichneumons develop inside the larvae of other ichneumons, which in turn develop in the body of caterpillars!

How birds take care of their chicks - Notes of a Naturalist

The Animal Friend book series, 1909

8507 Even an empty bird's nest, half hidden among tree branches or on the ground, in the grass under a bush, is a very attractive picture. But it is even nicer when colorful eggs lie in the cozy recess of the nest or small chicks sit, opening their noses wide to grab the food brought by their parents. I don't know almost a single picture from the life of animals that would tell us so convincingly and clearly about the love of parents for children.

How defenseless, how helpless is the little creature in most cases when it finally breaks through the calcareous shell that constrains it! Without the help of the parents who gave it life, it would soon die in the most miserable way. And how old people take care of their chicks! The thought of children fills their whole soul, starting from the moment when the first egg appears in a small airy cradle, and up to the moment when the chicks separate from their parents. All their thoughts and actions are aimed at bringing safety and protection to their helpless cubs, in order to feed hungry mouths, and later, when the chicks grow up, train them so that they can exist independently in the world and would not die in the harsh worldly storms, who are waiting for them.

Here is a little miller warbler, the smallest of our warblers, has built a nest in a low currant bush. We carefully part the branches of the bush: the warbler sits on the edge of the nest, holding food in its beak. We prevented her: she was just about to feed her cubs, which, with a squeak, stretch their ugly noses towards her. With its beautiful, intelligent eyes, a pretty bird gazes intently at a stranger who has invaded her possessions. The chicks also fell silent and drew back their outstretched necks. Nothing stirs; only the caterpillar is spinning, trying to escape from the bird's beak. But here we made a movement - and immediately broke the charm with this. Warbler falls from her place to the ground at our feet and, as if with broken limbs, helplessly jumps on the ground, dragging now her wing, now her leg. Isn't she trying to divert our attention from the nest and draw it to herself, to a sick creature with broken wings? An inexperienced person tries to follow a bird jumping on the ground, which tries to take him as far as possible from her chicks, and only then will she suddenly rise from the ground and disappear into a dense bush.

We prevented her: she was just about to feed her cubs, which, with a squeak, stretch their ugly noses towards her. With its beautiful, intelligent eyes, a pretty bird gazes intently at a stranger who has invaded her possessions. The chicks also fell silent and drew back their outstretched necks. Nothing stirs; only the caterpillar is spinning, trying to escape from the bird's beak. But here we made a movement - and immediately broke the charm with this. Warbler falls from her place to the ground at our feet and, as if with broken limbs, helplessly jumps on the ground, dragging now her wing, now her leg. Isn't she trying to divert our attention from the nest and draw it to herself, to a sick creature with broken wings? An inexperienced person tries to follow a bird jumping on the ground, which tries to take him as far as possible from her chicks, and only then will she suddenly rise from the ground and disappear into a dense bush.

And with what fearful cry the lapwings fly around us when we approach their nests! They fly very close to the enemy, they even pretend that they are going to attack him, as birds of prey do, so that a timid person positively rejoices when he manages to move away from the place where he was pursued from all sides by lapwings circling around him. with plaintive cries, and the lapwings only wanted him to leave: they hurriedly return to their nest, loudly rejoicing that they managed to avert a terrible danger from their children. Parental love makes them completely forget about the danger: courageous birds sometimes approach us so much that it seems that you can kill them with a stick. They also try to drive dogs away from their nests by attacking them. Often, lapwings, which are almost no larger than a domestic pigeon, even dare to make real attacks on dogs. More than once they have seen how they, running on the ground with outstretched wings in front of the dogs and jumping up, inflicted such blows with their beak on the head near the eyes that they put them to flight. If a separate lapwing, sitting on eggs, notices our approach only when we are already in front of it, then it begins to hobble around our feet back and forth, just as the whitethroat warbler and the rattle warbler do, in order to distract our attention from the eggs to himself, seemingly such a helpless creature.

with plaintive cries, and the lapwings only wanted him to leave: they hurriedly return to their nest, loudly rejoicing that they managed to avert a terrible danger from their children. Parental love makes them completely forget about the danger: courageous birds sometimes approach us so much that it seems that you can kill them with a stick. They also try to drive dogs away from their nests by attacking them. Often, lapwings, which are almost no larger than a domestic pigeon, even dare to make real attacks on dogs. More than once they have seen how they, running on the ground with outstretched wings in front of the dogs and jumping up, inflicted such blows with their beak on the head near the eyes that they put them to flight. If a separate lapwing, sitting on eggs, notices our approach only when we are already in front of it, then it begins to hobble around our feet back and forth, just as the whitethroat warbler and the rattle warbler do, in order to distract our attention from the eggs to himself, seemingly such a helpless creature.

Of course, it is hard to believe that a bird can reason in such a way that it deliberately uses this cunning, which would do as much credit to its mind as to its love for children. Therefore, perhaps, those who say that fear for children deprives the bird of reason, paralyzes its muscles, are right, so that the bird acts unconsciously. But why, then, does the bird noticeably try to move away from the nest?

One day, walking along the bank of a pond, I approached a place where a small company of seagulls was sitting on their eggs in the reeds. With a piercing cry, frightened birds rose into the air and began to circle around me, crying plaintively. At the same time, as it might seem, they also wanted to drive me away by throwing their liquid stools from above, which fell near me; one such projectile hit just on my hat. The same is said about terns. Of course, it may also be that the birds do not do this intentionally, but that this excretion is caused in them only by a feeling of fear. But however much we may belittle the mind of the bird in all the examples just given, one thing is certain, that the amazing behavior of birds during nesting is in any case very favorable for the preservation of their offspring, and that the fear that seizes the birds in this case is due only to tenderness. love for the chicks, overflowing with a small bird's heart.

But however much we may belittle the mind of the bird in all the examples just given, one thing is certain, that the amazing behavior of birds during nesting is in any case very favorable for the preservation of their offspring, and that the fear that seizes the birds in this case is due only to tenderness. love for the chicks, overflowing with a small bird's heart.

It is remarkable that among birds, not only the mother, but also the father devotes himself to the upbringing of the young. For the most part, both the male and the female take part in the construction of the nest. Often the male chooses a place for the nest and drags material for construction there, and the female, the main craftswoman in this matter, weaves and fastens the brought material together. Very often, the male and the female take turns sitting on the eggs, at least the male is ready every minute to help the female take her place if she needs to leave the nest for a short time.

And look how carefully the bird leaves its nest and returns to it again, how it takes care that the nest also does not catch the eye of any enemy while it is not there. The skylark never rises directly from the nest, but first runs some distance along the ground, hiding behind low grass or grain shoots, until finally it flies up. Returning back, he observes the same precaution, even when the chicks have already left the nest and, whistling softly, call their mother to her, she flies over the very grass not directly to the chicks, but to a place that is not far from them, and then already on the ground imperceptibly runs up to his children. Very many birds behave similarly to this if they have eggs or chicks, for example, water hens and others.

The skylark never rises directly from the nest, but first runs some distance along the ground, hiding behind low grass or grain shoots, until finally it flies up. Returning back, he observes the same precaution, even when the chicks have already left the nest and, whistling softly, call their mother to her, she flies over the very grass not directly to the chicks, but to a place that is not far from them, and then already on the ground imperceptibly runs up to his children. Very many birds behave similarly to this if they have eggs or chicks, for example, water hens and others.

Many birds, leaving their nest, at least for the shortest time, carefully cover the eggs from above with grass, leaves, and brushwood so that the eggs are not conspicuous.

Some hollow nesters very conscientiously carry away the droppings of chicks away from the nest. If the birds, when cleaning their nursery, simply threw out the sewage from the nest, then these sewage, accumulating near the nest, would often serve as a sure sign for various predators, betraying the presence of the nest. But smart birds do things differently.

But smart birds do things differently.

We are standing on the bank of a small pond. Here is a male of an elegant puffy tit, or chickadee, with a moth caterpillar in its beak, slipped into the hollow of a bird cherry tree to its chirping chicks and immediately appears again with a lump of droppings, the size of a pea, covered with a white mucous membrane. He releases it only when he is already flying over the water. Now a female appears with the same caterpillar in her beak; she also slips to her children and flies back from the nest with the same lump. This lump also disappears forever in the water. Young chicks in this respect are similar to those automatic selling devices that throw out some thing when a coin is lowered into the hole in the device. If you put a piece of food in the chick's mouth, then the swallowing movement that he does at the same time immediately causes movement in the back of the abdomen, and you can be almost sure that the short large intestine will immediately push out a lump of droppings, undigested remnants of food swallowed earlier.

You already know that brood birds remain in the nest only until they are thoroughly dry, and then, without any fuss, run away from it with their mother.

Quite different is the case with chicks. What helpless creatures their chicks are! They know only one thing: to open their noses wide in order to perceive food and drink. The parents feed them a curd-like substance, which is secreted in large quantities in pigeons when they have chicks, in the two lateral projections of their crop. It is a crumbly substance with the smell of rancid oil. It is sometimes called "milk", but in composition it has nothing to do with the milk of mammals, since it does not contain any casein or milk sugar contained in milk. In other birds, such as finches or plantains, the crop serves to soften the seeds in it before giving them to the chicks. This makes the food more digestible. And, for example, the crossbill, if it did not have an enlarged esophagus similar to a goiter, perhaps, could not feed its chicks at all. Klest often starts hatching chicks in winter, when he has only hard seeds of our coniferous trees at his disposal. This is not at all suitable food for small chicks, if the seeds were not first softened in the goiter. However, most granivorous birds, such as sparrows, finches, plantains, feed their chicks at first exclusively with insects, as a more digestible food, and only later move on to heavier food; although on the other hand there are birds such as, for example, linnet, which from the very beginning feed on plant foods.

Klest often starts hatching chicks in winter, when he has only hard seeds of our coniferous trees at his disposal. This is not at all suitable food for small chicks, if the seeds were not first softened in the goiter. However, most granivorous birds, such as sparrows, finches, plantains, feed their chicks at first exclusively with insects, as a more digestible food, and only later move on to heavier food; although on the other hand there are birds such as, for example, linnet, which from the very beginning feed on plant foods.

When, after a few weeks of careful care from their parents, the little chicks fledge and their dark eyes begin to boldly look at the world around them, some kind of unrest seizes the small children's society. It becomes crowded in the nest for everyone: one touches his neighbor with his wing, the other even tries to clear his place by force with the help of his legs. Finally, the strongest of the chicks squeezes upward from the tightness. Having made a big leap, he immediately reaches the edge of the nest or even sits already on a neighboring branch, looking around him with fear and at the same time pleased with his first feat, which he succeeded so much, as his parents assure him of this with their body movements and gentle inviting sounds. .

.

I have rarely been able to observe the flight of chicks from the nest. But still, I was lucky to see several times how young black redstarts dared to take the first step into the world around them, and once also how the chicks of the middle spotted woodpecker left their cradle; I also saw the first experiences of flight in young swallows. The chicks behaved very differently. One chick turns out to be quite skillful: it, apparently, already quite correctly determines distances, jumps from the first branch to the next, and even dares, encouraged by the voices of its parents, to flutter to a neighboring tree. As a reward for this, he receives a caterpillar. Another rushes swiftly out of the nest and falls, fluttering its wings, to the ground, perhaps into tall grass, from which it only manages to get out with difficulty. Only young swallows showed themselves, all without exception, born flyers from the very beginning; they climbed the wall of the nest, then spread their wings and flew to the edge of the roof, thence to the ridge of the roof, and after a short time many of them made the already safely difficult flight across the street to the roof of the house opposite. Very often it also happens that the chicks leave the nest immediately, being frightened of something, or the parents, bored with the fact that the chicks are too slow, push them over the edge of the nest themselves.

Very often it also happens that the chicks leave the nest immediately, being frightened of something, or the parents, bored with the fact that the chicks are too slow, push them over the edge of the nest themselves.

The well-known German aviologist Liebe beautifully describes how a pair of peregrine falcons taught their children to fly. Two young falcons perched on a horizontal branch of an old pine, looking about them half in curiosity, half in fear, while the old male reenacted before them his magnificent exercises in the art of flying. Did he want to teach the chicks this? Or did you want to inspire courage in them? “But then the female also appeared ... Having made several strokes in the air against the wind, she headed with the help of a skillful turn to the side, into the space behind the pine tree and then, slowly moving her wings, swam past one of the chicks, but so close to him that hit him with a wing and moved him from his place. But the chick firmly clung to the bough and, without releasing it, but only waving its wings in the air, again strengthened itself in its former position. Then the mother repeated the same attempt with another chick. This time she succeeded better: the mother very easily pushed the chick with her wing, I flew far down, describing a flat arc in the air. Now the mother took up the first chick again and pushed it off the branch in the same way as the other. The chick fell down, almost to the very ground, and again returned back to its branch, rising, apparently with difficulty and staggering, into the air against the wind. But the mother did not give him rest and again swam very close to him, without touching him with her wing, as if she wanted to show him how he should behave and how to move his wings.

Then the mother repeated the same attempt with another chick. This time she succeeded better: the mother very easily pushed the chick with her wing, I flew far down, describing a flat arc in the air. Now the mother took up the first chick again and pushed it off the branch in the same way as the other. The chick fell down, almost to the very ground, and again returned back to its branch, rising, apparently with difficulty and staggering, into the air against the wind. But the mother did not give him rest and again swam very close to him, without touching him with her wing, as if she wanted to show him how he should behave and how to move his wings.

After the chicks leave the nest, the parents continue to feed them for some time. Then one can see how, for example, young redstarts, resembling small round balls of feathers, of which only a nose with a yellow border and a blunt tail stick out, sit on the fence of the garden and beg food from their parents with trembling movements, or like little swallows huddled close to each other on the crest of the roof, watching the old swallows hunt for insects, and with their diligent chirping let every swallow flying past know about their desire to get a tasty piece.

Even the sight of young sparrows sitting in the dust of the street and never ceasingly pestering with their importunate requests not only to their own mother, but to every adult sparrow, can give great pleasure. Fluttering their wings, little sparrows jump after adult sparrows, expressively shouting out their invariable: “give, give!” More than once I have observed how little screamers pestered even finches and buntings and sought from them the satisfaction of their request. And once I even saw young sparrows begging for their food from a crested lark. And the lark had no choice but to get rid of the little beggars, but to give them a few pieces.

Among the brood birds, too, the parents tenderly care for their children and teach them all the arts that may be useful to them later. First of all, we can point here to chicken birds. And if in chicken birds the father usually does not care at all or cares very little about his children, then, on the other hand, the mother devoted to them tries to make up for the lack of father's love with redoubled solicitude.

On the other hand, among partridges, the male takes care of his children in the same way as the female. Fearfully looking out from which side trouble threatens them, and whether it is possible to avert it, the father runs hither and thither, while the mother, with a short warning cry, gathers the chickens around her, orders them to hide in some secret place and quickly points out to each of them shelters in grass, in grain crops, among bushes, in furrows, ruts, and so on. And when the mother finally decides that all her children are well hidden, she, together with the father, exerts all her strength to frustrate the enemy’s plan or repel the attack ... If the father thinks that the danger has passed, he begins to call the chickens to him; one after another, the chicks answer him, and the loving parents gradually gather the entire scattered company back into one place, and the father brings the children one by one and takes them to the mother, who at that time is looking after those chicks that the father has already brought to her.

And how tenderly all the swimming birds treat their young! Their chicks know how to swim from the very first day; but many aquatic birds must still learn how to dive, in order to save themselves from dangers under water and look for their food there. For example, a grebe begins training its chicks to dive by taking them under its wings and diving with them until the chicks finally lose all fear of the dark abyss and dare to do the same on their own. If the little fluffy chicks want to take a break from their exercises, they climb onto the soft and warm back of their mother or father, who continue to calmly float on the water with their expensive burden on their backs.

When, after a while, the chicks learn everything they need to know in life, their connection with their parents is interrupted. The children, carefully guarded until now, now go their own way. And if sometimes some capricious little chick still tries to hold onto its mother's skirt, as, for example, is very often observed among sparrows, then the mother angrily throws it away with its beak.