When did baby food first come out

The history of commercial baby food in the US

Photo: Thomas Hawk / Flickr

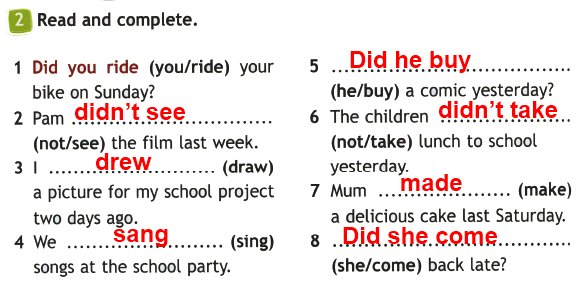

Popular since its invention in the early 20th century, commercial baby food was seen as a product of convenience for women. "They were advertised as safe, modern and better than you could prepare at home," says Amy Bentley, author of Inventing Baby Food and associate professor in the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies and Public Health at New York University.

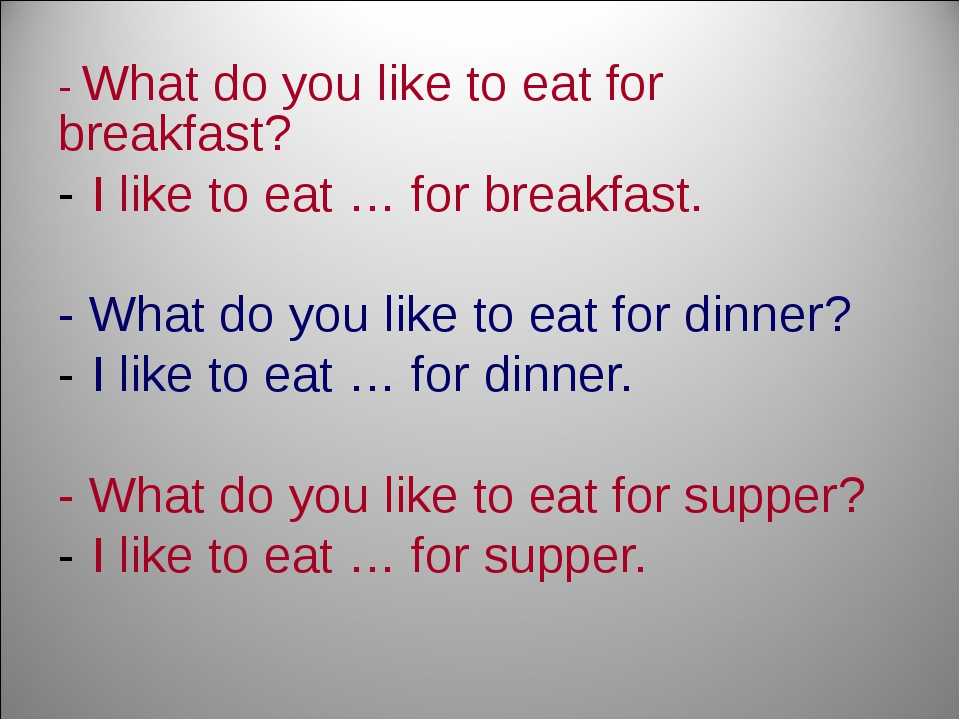

Noelle Carter: What did we do before commercial baby food? How did babies eat, and when did mothers introduce their babies to solid food?

Amy BentleyAmy Bentley: Commercial baby food started in the early 20th century, in the late 1920s. Before then, there wasn't a category specifically called "baby food." There was a category of soft foods -- foods that were appropriate for infants, invalids and the elderly.

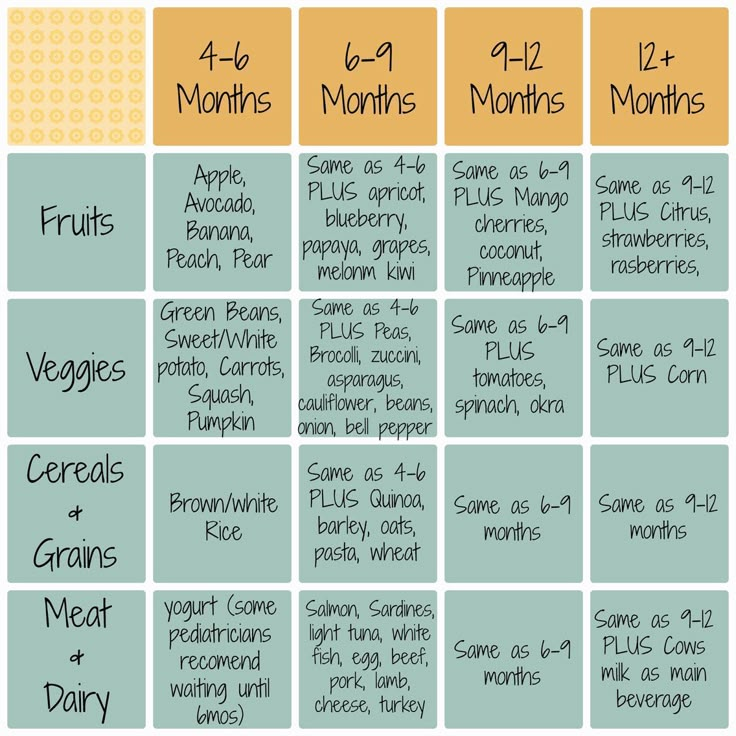

But the advice and practice of the late 19th century was really that you didn't feed babies solid food until about 1 year of age.

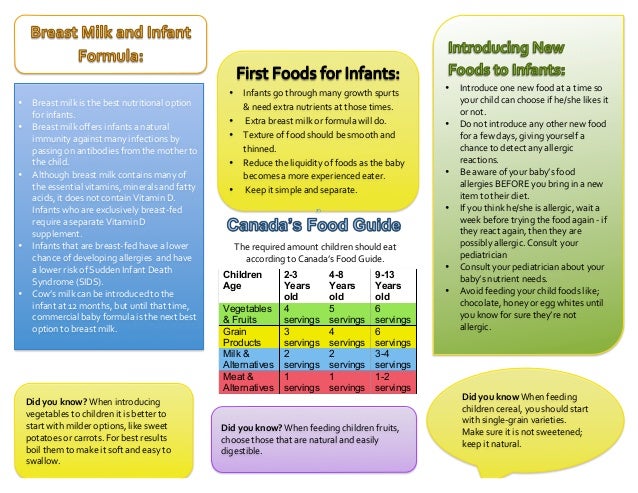

You were supposed to breastfeed them -- or use formulas, if you absolutely had to. It was thought that solid food wasn't needed until later. In fact, there was advice in practice that you did not feed children fruits and vegetables until about 2 years of age.

NC: How did commercial baby food come to be?

AB: As vitamins were discovered in the 19-teens, that was also about the time you had the industrialization of the food supply. Those products were more widely available and more affordable.

There was a man named Harold Clapp in Rochester, New York, whose child was sick. He created a soup for his child made of vegetables. It proved so popular that his friends asked him for it. He went to the local cannery and commercially prepared this product.

That was also about the same time that the Gerber Products Company was starting to produce baby food. Others just picked it up, and eventually you had the development of three or four really big commercial brands.

But it was very, very popular from the get-go.

The products were portable and convenient. They were advertised as safe, modern and better than you could prepare at home. They were seen as a product of convenience for women. Women could put them in their bags, remove themselves from the kitchen and travel around. It eventually made it easier for them to go outside and perform paid labor because they had this portable baby food.

NC: Baby food was incredibly popular until the 1970s. Then, all of a sudden, the use of baby food and a number of other things came into question. What happened?

AB: Through the mid-20th century, the average age of when it was understood you could feed a baby solids begins to drop dramatically. Whereas, in the early 20th century, the average age of feeding an infant solids is around 9 to 12 months of age, by the 1950s and '60s, the average age of introducing solids to a baby is 4 to 6 weeks of age.

There are some doctors who are promoting introducing solids at 24 hours after birth.

"Once infants go off baby food, one of the top three vegetables they consume is french fries."

-Amy BentleyThis was because baby food was thought to be strong and healthy. Solid food was better than liquid formula. Most parents formula-fed their babies in the mid-20th century, so commercial solid food was the next step. There was no scientific evidence that this was harmful for a child.

Then, in the Cold War period, there was this idea that we need our children strong and we need them to be competitive. "I might be doing my baby a disservice if I don't feed my child commercial baby food early."

This begins to change in the 1970s and '80s as you have a general ethos that's a little more mistrustful of science and institutions, and skeptical of technology. Women start to ascribe to an ethos called natural motherhood. "I should trust my instincts; I know better than anything how I should feed my baby.

"

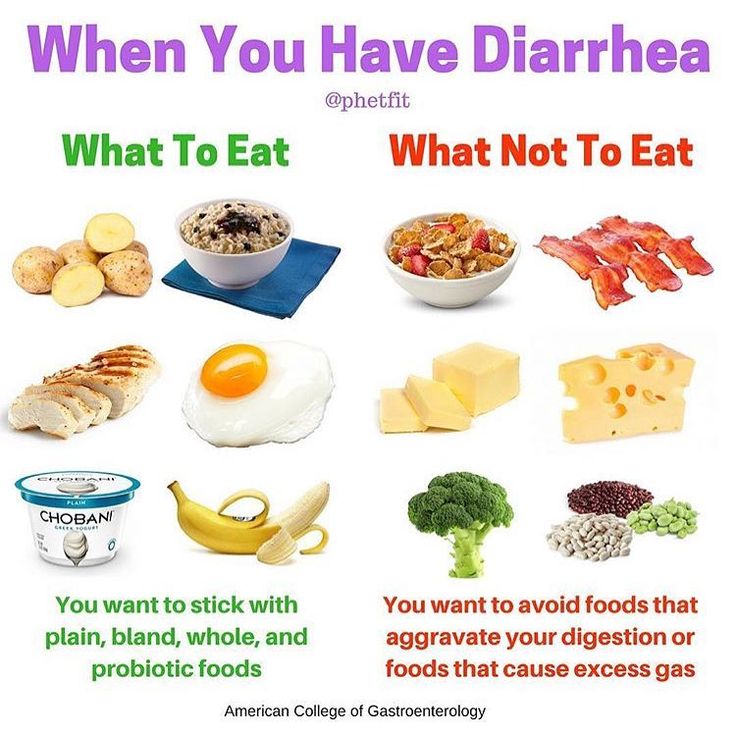

There begins to be some scientific evidence that it probably is not the best thing to feed an infant solids so early. This is, in part, because of the way that baby food is made during that period, which is with a lot of additives, sugar and salt. Also, an infant's digestive system is not equipped to digest solid food so early. The best food is breast milk.

Eventually they figure it out, so consumers push against the conventional baby food. They make their own baby food. The commercial manufacturers begin to take out sugar and salts, and begin to remove baby food desserts. Then you have a different era of what baby food should be, like: How I should feed my child and when I should feed my child baby food.

NC: You discussed the connection between commercial baby food and the industrialized palate. How might food choices -- baby food or even formula -- play a role in developing a child's sense of taste?

Inventing Baby FoodAB: Scientists are finding out that infants learn, grow and develop through taste, through their palates, even in utero.

We know that amniotic fluid is flavored by the food a woman eats. After birth, the foods that a child is exposed to have a big influence on how that child is learning, developing and understanding the world.

If children are only experiencing highly industrialized food products with milder profiles, more salt, more sugar and refined carbohydrates, then that's what their palates are becoming even more accustomed to. As humans, we're hard-wired to seek out sugar and eventually salt. But we need to learn to become acclimated to bitter flavors, sour flavors and a variety of profiles.

[Related story: It may take 10 tries to familiarize picky eaters with new foods]

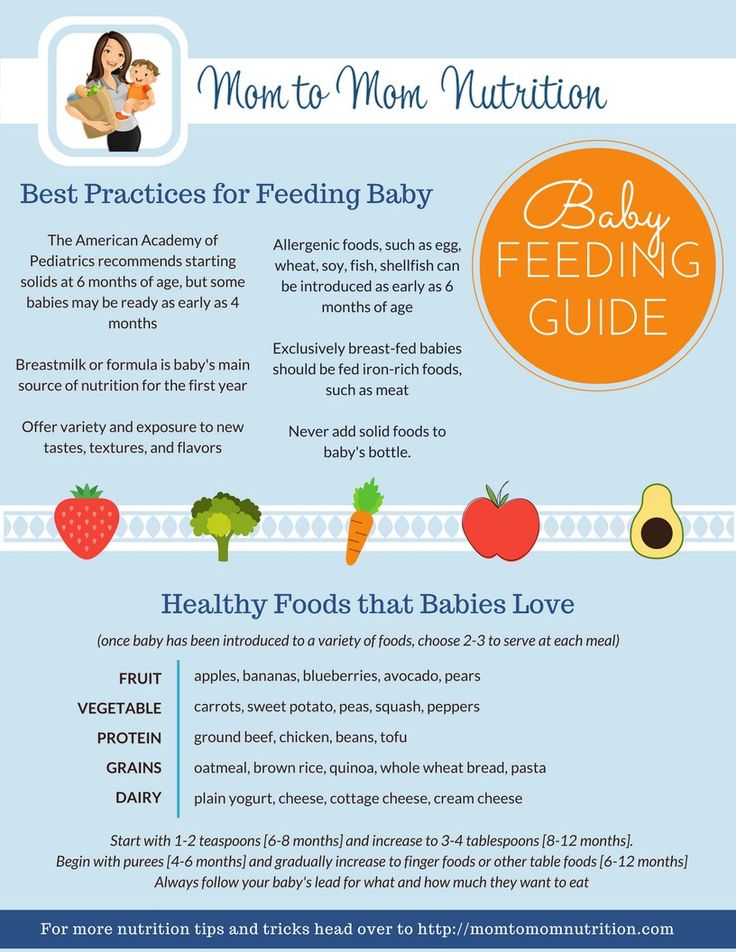

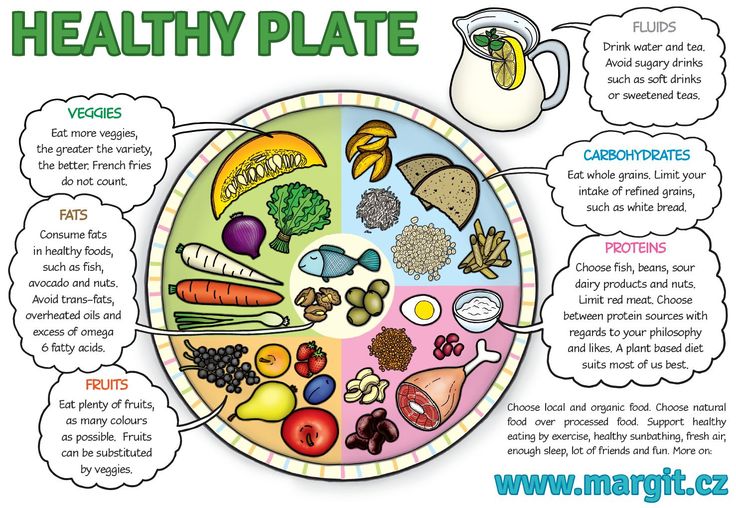

There's more and more emphasis on first foods being something other than white rice cereal, for instance -- an avocado, meat or a red or an orange fruit or vegetable. There is no real scientific evidence that these can't be used as first foods. In fact, if we look around the world, we find that people feed their infants a wide variety of different kinds of first foods, including some very interesting spice combinations.

NC: Where do you see the trend in baby food going?

AB: In the last couple of decades, there's really been a rise of boutique baby foods that experiment with different flavors, grains and vegetables. Commercial baby foods are also expanding their repertoire.

There's also a group that understands there wasn't a category called baby food in the beginning, and maybe are arguing that there doesn't need to be a category called baby food. This is a trend called baby-led weaning. Those people advocate that infants be breastfed until about 6 months of age. Then you can just sit that child in a high chair, chop up table food, throw it on the high chair and the baby will be just fine.

That said, baby food is not going to go away because it is important for some children. Also, it is a product of convenience. In the U.S., we're very much attuned to convenience and mobility. These products allow women especially more flexibility with their lives.

Some studies show that baby food actually does provide a wider range of fruits and vegetables for infants than otherwise. You can buy a jar of mangos or a jar of beets. A lot of families don't have a very wide variety of fruits and vegetables. Once infants go off baby food, one of the top three vegetables they consume is french fries. Baby food can actually have a protective quality for a lot of American infants.

Each week, The Splendid Table brings you stories that expand your world view, inspire you to try something new and show how food brings us together. We rely on you to do this. And, when you donate, you'll become a member of The Splendid Table Co-op. It's a community of like-minded individuals who love good food, good conversation and kitchen companionship. Splendid Table Co-op members will get exclusive content each month and have special opportunities for connecting with The Splendid Table team.

Donate today for as little as $5.00 a month. Your gift only takes a few minutes and has a lasting impact on The Splendid Table and you'll be welcomed into The Splendid Table Co-op.

The Food Timeline--baby food history notes

The Food Timeline--baby food history notes FoodTimeline libraryPeoples of all times and places have been feeding their babies. With the exception of mother's (or wet nurse's) milk, what was served and how it was made, was a function of culture, cuisine and economic status. Babies in Ancient Egypt thrived on different foods from those in Medieval England, Jomon Japan, 18th century Russia and early 20th century Kenya.

Up until the middle of the 19th century [in industrialized nations] infant food was generally made at home. Recipes and instructions for feeding babies were sometimes found in cookbooks. These foods were often grouped with invalid cookery. Why? They were generally thought to have similar properties. Both were highly nutritious and easily digested. Finely ground grains (oats, rice, barley) mixed with a liquid are found in most cultures. Example: Cookery for Children, Sarah Josepha Hale, 1852.

Food historians generally agree that manufactured baby food, as we know it today, was a byproduct of the European Industrial Revolution. The first mass-produced baby foods were invented by scientists/nutrition experts and manufactured in the mid-19th century by innovative companies. These were infant formulas, substitutes for mother's milk. At that time, tainted milk was often connected with infant mortality. Then, as now, there was much controversy regarding the use of artifical baby food. Ideas regarding amounts, timing, and what consitituted a healthy diet have likewise changed.

By the 1920s infant foods, which had grown to encompass ready-made baby cereals, fruits and vegetables, were promoted as convenience items. Food companies capitalized on "modern" notions of scientific feeding and the superiority of manufactured items over those homemade. Interestingly enough? American consumers did not immediately embrace these new foods. It took some very agressive marketing to win them over.

Some foods we regard today as sweets were originally marketed as health foods for children. Two cases in point: malted milk and chocolate pudding.

RECOMMENDED READING:

- "History of the Development of Infant Formulas," Infant Formula: Evluating the Safety of New Ingredients, Food and Nurition Board

- "Infant and Child Nutition," Cambridge World History of Food, Kiple & Ornelas, Volume Two, section VI.7 (p. 1444-1453)

---traces the history of infant feeding from prehistory to present; includes extensive bibliography for further study - Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Andrew F. Smith, Volume 1 "Baby Food," (p. 57-59_ ---excellent overview; includes selected bibliography

- History of the feeding bottle, The Baby Bottle Museum, UK

A SHORT SURVEY OF MANUFACTURED BABY FOODS THROUGH TIME

[1867] LIEBIG'S SOLUBLE FOOD FOR BABIES/LONDON

"Perhaps not surprisingly, a major step in capitalization on the new advances in chemistry by marketing proprietary infant foods came from the scientist who laid the foundations of the New Newtrition, Baron Justus von Liebig. If indeed foods were constituted of protein, carbohydrates, and fats, could these nutrients not be combined into a replica of mother's milk? Thus, in 1867 the Baron introduced Liebig's Soluble Food for Babies in the European market. By the next year it was being manufactured and sold in London by the Liebig's Registered Concentrated Milk Company and within a year after that it had migrated to the United States. Liebig did not challenge the prevalent notion that mother's milk was the perfect infant food. Rather, he claimed that he had succeeded in concocting a substance, at first liquid, then powdered, whose chemical makeup was virtually identical to that of mother's milk. Liebig's Food was soon followed by a host of imitators. Some contained dried milk and called only for the addition of water. Others, like Liebig's original formula, were to be added to diluted milk. Soon some doctors were proclaiming these foods to be superior to the milk of wet nurses."

If indeed foods were constituted of protein, carbohydrates, and fats, could these nutrients not be combined into a replica of mother's milk? Thus, in 1867 the Baron introduced Liebig's Soluble Food for Babies in the European market. By the next year it was being manufactured and sold in London by the Liebig's Registered Concentrated Milk Company and within a year after that it had migrated to the United States. Liebig did not challenge the prevalent notion that mother's milk was the perfect infant food. Rather, he claimed that he had succeeded in concocting a substance, at first liquid, then powdered, whose chemical makeup was virtually identical to that of mother's milk. Liebig's Food was soon followed by a host of imitators. Some contained dried milk and called only for the addition of water. Others, like Liebig's original formula, were to be added to diluted milk. Soon some doctors were proclaiming these foods to be superior to the milk of wet nurses."

---Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet, Harvey Levenstein [Oxford University Press:New York] 1988 (p. 122-3)

122-3)

About Justus von Liebig.

[1867] NESTLE'S MILK FOOD/SWITZERLAND (powdered)

"In 1867, the Swiss merchjant Henri Nestle invented the first artificial infant food, and in 1873, 500,000 boxes of Nestle's Milk Food were sold in the United States as well as in Europe, Argentina, and the Dutch East Indies. By the late 1880s, several brands of mass- produced foods, mostly grain mixtures to be mixed with milk or water, were on the market. These included Liebig's Food, Carnick's Soluble Food, Eskay's Albumenized Food, Imperial Granum, Wagner's Infant Food and Mellin's Food. Mellin's was perhaps the most widely used."

---Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Andrew F. Smith editor [Oxford University Press:New York] 2004, volume 1 (p. 57)

"In 1867, Henri Nestle, a pharmacist, was asked by a friend to make something for an infant who could not digest fresh cow's milk...Nestle created a milk food form crubs made from baked malted wheat rusks mixed with sweetened condensed milk. This granular brown powder was the first instant weaning food. He dalled his alternaive to breast-feeding Farine Lactee Henri Nestle and adopted his family's coat of arms, a bird's nest, as a trademark...Nestle sold his company to Jules Monnerat in 1874."

This granular brown powder was the first instant weaning food. He dalled his alternaive to breast-feeding Farine Lactee Henri Nestle and adopted his family's coat of arms, a bird's nest, as a trademark...Nestle sold his company to Jules Monnerat in 1874."

---Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Andrew F. Smith editor [Oxford University Press:New York] 2004, volume 2 (p. 180)

[1874] MELLIN'S FOOD/United Kingdom

"The exhibits of Mellin's food in the Mechanics and Instituted exhibitions now in progress have attracted the attention of thousands of visitors, and the people are beginning to examine and discuss the suggestive topic which the displays suggest. Time and experience have put this food to a successful test, and its important bearing upon the rising and future generations cannot be oversetimated. Its history proves again that it is almost invariably the case that a really good article is slow in making its way into the favor of the public, but, when finally its excellences are known, its success is assured and the rapidity of its introduction marvellous. This is notably the case with the article which is known as Mellin's food, and which is now being so generally received into public favor. For years it has been a deplorable but acknowldged fact, that an alarming percentage of children die before reaching the age of five years. In England, the number of children that die under one year old is in the ratio of one to every twelve births...Liebig's food,...came the nearest to a practical solution of the difficult problem, but it was unsuitable for distribution and exportation, and much trouble and a sacrifice of time were entailed by its daily preparation. G. Mellin of London, following Liebig's suggestions, produced an article which is portable, easy of preparation, and which gives entire satisfaction. Mellin's food, requires neither boiling nor straining, that having already been done, but is almost instantly prepared for use by dissolving a certain quantity in hot water and then adding cold milk. Analysis of the food after mixing shows it to contain a large proportion of grape sugar, which enters so largely into the composition of mother's milk, together with a large amount of protein and soluble phosphates, indicating flesh and bone forming nutrients of the highest type.

This is notably the case with the article which is known as Mellin's food, and which is now being so generally received into public favor. For years it has been a deplorable but acknowldged fact, that an alarming percentage of children die before reaching the age of five years. In England, the number of children that die under one year old is in the ratio of one to every twelve births...Liebig's food,...came the nearest to a practical solution of the difficult problem, but it was unsuitable for distribution and exportation, and much trouble and a sacrifice of time were entailed by its daily preparation. G. Mellin of London, following Liebig's suggestions, produced an article which is portable, easy of preparation, and which gives entire satisfaction. Mellin's food, requires neither boiling nor straining, that having already been done, but is almost instantly prepared for use by dissolving a certain quantity in hot water and then adding cold milk. Analysis of the food after mixing shows it to contain a large proportion of grape sugar, which enters so largely into the composition of mother's milk, together with a large amount of protein and soluble phosphates, indicating flesh and bone forming nutrients of the highest type. ..Thus sucenc e finally conquered all difficulties, and produced a food that all mothers will hail with delight. Not until 1874 did it make its appearance in this country, and then through the enterprises of Theodore Metcalf & Co., who, in response to the growing demand, obtained the North American agency. In order to supply the greatly increased demand in Europe and America for this food the proprietor was obliged to erect larger works, and since 1877 the food has been regularly supplied....The best medical men in the country now acknowledge its merits and prescribe it in cases where formerly they were almost helpless."

..Thus sucenc e finally conquered all difficulties, and produced a food that all mothers will hail with delight. Not until 1874 did it make its appearance in this country, and then through the enterprises of Theodore Metcalf & Co., who, in response to the growing demand, obtained the North American agency. In order to supply the greatly increased demand in Europe and America for this food the proprietor was obliged to erect larger works, and since 1877 the food has been regularly supplied....The best medical men in the country now acknowledge its merits and prescribe it in cases where formerly they were almost helpless."

---"A Public Benefactor: An Exhibit at the Fair--Mellin's Food for Infants...", Boston Daily Globe, November 6, 1881 (p. 5)

"The Duty of Every Mother and especially those who are charged with the delicate and great responsibility of rearing hand-fed children, is to investigate the merits of the best artificial food for the preservation of infant life. The universal testimony of our most skillful physicians, and of thousands of mothers who have practially tested it, demonstrated beyond a doubt that Mellin's Food for Infants is the best, and contains exactly the ingredients necessary to insure the life and health of the little ones to develop them in body and mind, and secure robust health in childhood, manhood and womanhood."

The universal testimony of our most skillful physicians, and of thousands of mothers who have practially tested it, demonstrated beyond a doubt that Mellin's Food for Infants is the best, and contains exactly the ingredients necessary to insure the life and health of the little ones to develop them in body and mind, and secure robust health in childhood, manhood and womanhood."

---display ad, Theodore Metcalf & Co., 39 Tremont St., Boston Mass., "Sole agents for the United States and British America," Boston Daily Globe, April 11, 1880 (p. 30) [NOTE: this ad contains physican testimonials.]

"By the 1890s the most popular by far of the powders to be added to milk was Mellin's Food, developed in England and manufactured in Boston, whose advertisements claimed that it was "the genuine Liebig's Food," The best known of the dried-milk products was another European import, Nestle's Milk Food, which was manufactured and distributed under license by a New York City firm. Advertisements for various proprietary infant foods because well-nigh ubiquitious by the 1890s....Nestle's ("Best for Babies") said it was better for babies than milk, for "impure milk in hot weather is one of the chief causes of sickness among babies."...A favorite promotional technique was to offer free samples by mail to the readers of middle-class magazines. Perhaps the most effective with middle-class mothers...were the free handbooks on infant care feeding distributed by the companies. Mellin's with its own press, was especially active in this field. The handbooks explained the chemistry of milk and feeding in clear but relatively sophisticated language, adding an aura of science to the food they were promoting. Not only did they prove effective in convincing mothers of the efficacy of proprietary infant foods, they convinced many doctors as well...Thus, by the 1980s a number of sources spread the growing impression that artificial feeding was both scientific and modern."

Advertisements for various proprietary infant foods because well-nigh ubiquitious by the 1890s....Nestle's ("Best for Babies") said it was better for babies than milk, for "impure milk in hot weather is one of the chief causes of sickness among babies."...A favorite promotional technique was to offer free samples by mail to the readers of middle-class magazines. Perhaps the most effective with middle-class mothers...were the free handbooks on infant care feeding distributed by the companies. Mellin's with its own press, was especially active in this field. The handbooks explained the chemistry of milk and feeding in clear but relatively sophisticated language, adding an aura of science to the food they were promoting. Not only did they prove effective in convincing mothers of the efficacy of proprietary infant foods, they convinced many doctors as well...Thus, by the 1980s a number of sources spread the growing impression that artificial feeding was both scientific and modern."

---Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet, Harvey Levenstein [Oxford University Press:New York] 1988 (p. 124)

124)

[NOTE: This book contains much more information on this topic. If you need more details ask your librarian can help you obtain a copy.

How much did these powdered formulas cost? Advertisement published in the New York Times, Marh 30, 1884 (p. 3) states: Nestle's Milk Food, 70 cents--$1.00; mellin's Food, 30 cents-50 cents. Horlick's Food, 65 cents-$1.00.

Our survey of historic American newspapers reveals the Boston-based firm Dolibar, Goodale & Co. [41 Central Warf] was a distribtor for Mellin's in 1884. Articles and advertisements confirm Doliber continued to distribute Mellin's food at least until 1906.

[1893] AMERICAN DIETARY RECOMMENDATIONS

"Farinaceous Foods. There are many farinaceious forms of food prepared fo r the use of infants and children. Probably the most valuable of them are those made according to the Leibig process. The starch of the grain from wich such foods are prepared is, int he process of manufacture, changed into soluble detrine, or sugar (glucose), by the action of the diastase of malt: the very thing which an infant cannot do. When we consider that the digestion of starch in the alimentary canal consists of this change into glucose, and that it is effected principally by the saliva and the pancreatic juice, the significance of the value of such foods will be seen...Mellin's food and malted mlk are prepared according to the Liebig process. in them the starch has been converted into soluble matter by teh action of the ferment of maltk. It is really a partial predigestion. Mellon's food does not contain milk...Mellin's food bears comparison with nilk. It is easily digested, and as an attenuant for milk may be used without harm during the early months of life, but it should not be used to the exclusion of milk for more than a few days at a time, and then only when milk is not retained by the stomach. Later it is doubtless a valuable addition to the regular daily food of the child. Malted milk is made form selected grain and desiccated or dried milk. To prepare it for the infant it needs only the addition of water.

When we consider that the digestion of starch in the alimentary canal consists of this change into glucose, and that it is effected principally by the saliva and the pancreatic juice, the significance of the value of such foods will be seen...Mellin's food and malted mlk are prepared according to the Liebig process. in them the starch has been converted into soluble matter by teh action of the ferment of maltk. It is really a partial predigestion. Mellon's food does not contain milk...Mellin's food bears comparison with nilk. It is easily digested, and as an attenuant for milk may be used without harm during the early months of life, but it should not be used to the exclusion of milk for more than a few days at a time, and then only when milk is not retained by the stomach. Later it is doubtless a valuable addition to the regular daily food of the child. Malted milk is made form selected grain and desiccated or dried milk. To prepare it for the infant it needs only the addition of water. It is probably one of the best substitutes for milk but should not be used for any length of time when it is possible to get good milk....Nestle's food, Imperial Granum, Ridge's food, and some others are made very carefully from selected wheat by this process. Nestle's food contains dried milk. These foods are all valuable when made into gruel or porridge, but should be used very sparingly under the age of twelve months, and then only as attenuants ofr milk, not as substitutes for it. Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, editor of 'Domestic Hygiene of the Child,' by Uffelmann (a translation), in speaking of the value of the various preparations of infants' food on the market says: 'There is not the slightest reason to prefer them to milk or its preparations, except that the latter requires more care; and for any intelligent and affectionate mother this reason is quite insufficient."

It is probably one of the best substitutes for milk but should not be used for any length of time when it is possible to get good milk....Nestle's food, Imperial Granum, Ridge's food, and some others are made very carefully from selected wheat by this process. Nestle's food contains dried milk. These foods are all valuable when made into gruel or porridge, but should be used very sparingly under the age of twelve months, and then only as attenuants ofr milk, not as substitutes for it. Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, editor of 'Domestic Hygiene of the Child,' by Uffelmann (a translation), in speaking of the value of the various preparations of infants' food on the market says: 'There is not the slightest reason to prefer them to milk or its preparations, except that the latter requires more care; and for any intelligent and affectionate mother this reason is quite insufficient."

---A Handbook of Invalid Cooking, Mary A. Boland [Century Co.:New York] 1893, 1898(p. 289-292)

[1924] SPECIAL INFANT FOODS

"Of the many patent infant and invalid foods on the market, some consist of cow's milk combined with varying amounts of carbohydrates of other materials and others seem to be made of starchy materials without milk. In some cases the carbohydrates have apparently been malted before being combined with milk, or else malt extract is added during the process of manufacture. Experience had shown that these special foods, when they contain nutrietns of milk, are sometimes valuable for infants when it is necessary to resort to artificial feeding. Too much faith should not be put in the extravagant claims made for some brands of infant foods. The safest course is to follow the advice of a competent physician in selecting the substitute for natural feeding. It is often wiser to use cow's milk, modified at home under a physician's direction, rather than these commercial foods."

In some cases the carbohydrates have apparently been malted before being combined with milk, or else malt extract is added during the process of manufacture. Experience had shown that these special foods, when they contain nutrietns of milk, are sometimes valuable for infants when it is necessary to resort to artificial feeding. Too much faith should not be put in the extravagant claims made for some brands of infant foods. The safest course is to follow the advice of a competent physician in selecting the substitute for natural feeding. It is often wiser to use cow's milk, modified at home under a physician's direction, rather than these commercial foods."

---Milk and Its Uses in the Home, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farmers' Bulletin No. 1359 [Government Printing Office:Washington DC] revised January 1924 (p. 15) [NOTE: This booklet also states "That the best food for an infant is milk from a strong, healthy woman is admitted by everyone. When it is not obtainable, the more nearly the substitute resembles it the better. Cow's milk is the most common substitute, and when necessary may be artificially modified. Goat's milk, too, is in some cases recommened for infants." (P. 5)]

Cow's milk is the most common substitute, and when necessary may be artificially modified. Goat's milk, too, is in some cases recommened for infants." (P. 5)]

[1928] GERBER'S/United States

Gerber's launched its new baby food line in 1928 with a special promtion intended to get mothers to try the product and create a demand for the item in retail grocers stores: About Gerber's.

"1928: Danel Gerber improves baby foods with improved methods for straining peas and finds by a maket surey that a large market exists for such foods if they can be cold cheaply through grocery stores. Gerber advertises in Child's Life magazine and offers six cans for a dollar (less than half the pices of baby foods sold at pharmacies) to customers will send in coupons filled out with the names and addresses of their grocers."

---The Food Chronology, James Trager [Henry Holt:New York] 1995 (p. 455)

"By the late 1920s, commercially canned baby food was introduced and quickly adopted by American consumers. Conditions were favorable: advertising had become widespread, the cost of canned foods had fallen, and experts recommended the addition of fruits and vegetables to the infant diet. The Gerber Company initiated this revolution in infant feeding by expanding the scope of the canned foods industry. According to the Gerber company history, in 1927 Dorothy Gerber laboriously hand-strained vegetables for her seven-month-old daughter, Sally, and urged her husband, Daniel, to consider manufacturing stained baby food a the Gerber family's Fremont Canning Company. The next year, the company introduced strained peas, prunes, carrots, and spinach to the market. The Gerbers launched an advertising campaign featuring a sketch of an infant known as the Gerber Baby that ran in such publications as Good Housekeeping, The Ladies' Home Journal, the Journal of the American Dietetics Association, and the Journal of the American Medical Association. The Gerber Baby icon, drawn by Dorothy Hope Smith, became the company's official trademark in 1931.

Conditions were favorable: advertising had become widespread, the cost of canned foods had fallen, and experts recommended the addition of fruits and vegetables to the infant diet. The Gerber Company initiated this revolution in infant feeding by expanding the scope of the canned foods industry. According to the Gerber company history, in 1927 Dorothy Gerber laboriously hand-strained vegetables for her seven-month-old daughter, Sally, and urged her husband, Daniel, to consider manufacturing stained baby food a the Gerber family's Fremont Canning Company. The next year, the company introduced strained peas, prunes, carrots, and spinach to the market. The Gerbers launched an advertising campaign featuring a sketch of an infant known as the Gerber Baby that ran in such publications as Good Housekeeping, The Ladies' Home Journal, the Journal of the American Dietetics Association, and the Journal of the American Medical Association. The Gerber Baby icon, drawn by Dorothy Hope Smith, became the company's official trademark in 1931. "

"

---Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Andrew F. Smith editor [Oxford University Press:New York] 2004, Volume 1 (p. 58-9)

Who was the original Gerber Baby?

Ann Turner Cook, the neighbor of Boston artist Dorothy Hope Smith. Ms. Cook grew up to be a teacher.

"The Gerber babythe face that launched a brand The tousled hair, the bright eyes, the round, pursed lips. The Gerber baby is recognized all around the world. So who is this special baby? People polled throughout the United States surmised that the Gerber Baby had to have grown up to become someone famous: Guesses ranged from movie stars Humphrey Bogart and Elizabeth Taylor to Senator Bob Dole. But mystery novelist and retired English teacher Ann Turner Cook knows the real answer. Because she is the Gerber Baby. The back-story on the Gerber Baby In 1928 Gerber was looking for a face to represent a baby food ad campaign. The baby Ann Turner Cook posed for artist Dorothy Hope Smith. Her simple charcoal sketch competed with lots of portraits, including elaborate oil paintings. (Smith offered to finish the sketch if it were accepted.) Whether it was the simplicity of the drawing or the cuteness of the baby (or both!), the judges fell in love with the adorable cherub face of Ann Turner Cook. They were so taken with it that Smith didnt have to finish the sketch. Gerber used it just as it was. The illustration became so popular that Gerber adopted it as its official trademark in 1931. Since then the Gerber Baby has appeared on all GERBER packaging and in every Gerber advertisement, making Ann Turner Cook the worlds best-known baby image. Her sparkling eyes and inquisitive look personify Gerbers commitment to happy and healthy babies all over the world."

(Smith offered to finish the sketch if it were accepted.) Whether it was the simplicity of the drawing or the cuteness of the baby (or both!), the judges fell in love with the adorable cherub face of Ann Turner Cook. They were so taken with it that Smith didnt have to finish the sketch. Gerber used it just as it was. The illustration became so popular that Gerber adopted it as its official trademark in 1931. Since then the Gerber Baby has appeared on all GERBER packaging and in every Gerber advertisement, making Ann Turner Cook the worlds best-known baby image. Her sparkling eyes and inquisitive look personify Gerbers commitment to happy and healthy babies all over the world."

Gerber's Heritage

"The most enduring urban legend about the famous Gerber Baby has to be the one about Humphrey Bogart. It's been said that the image on the labels actually was a diaper- clad Bogie, sketched lovingly by his artist mom. Trouble is, the tough-guy actor was already a grown man when the first Gerber jars appeared on store shelves in 1928. Ann Turner Cook -- the real, honest-to-goodness Gerber Baby -- has heard all the face tales. Her cherubic face as a happy infant is forever etched in time on every label of every Gerber product sold in 80 countries, one of the most famous and enduring trademarks in history. These days, Cook is an energetic 77-year-old fledgling novelist who's not above using her notoriety as America's most famous baby to drum up interest in her murder mysteries, featuring an erstwhile female reporter sniffing out intrigue in small Florida towns....The daughter of well-known comic strip artist Leslie Turner, Cook taught literature and writing in Tampa schools for 26 years and raised four children. Since retiring in 1989, she has published two novels regionally, with a third in the works. But Cook will no doubt always be best known for her picture on the Gerber labels. Cook was about 4 months old in 1927 when family friend Dorothy Hope Smith sketched the image in charcoal. Using a neighbor's baby as a model wasn't so unusual in the artist enclave of Westport, Conn.

Ann Turner Cook -- the real, honest-to-goodness Gerber Baby -- has heard all the face tales. Her cherubic face as a happy infant is forever etched in time on every label of every Gerber product sold in 80 countries, one of the most famous and enduring trademarks in history. These days, Cook is an energetic 77-year-old fledgling novelist who's not above using her notoriety as America's most famous baby to drum up interest in her murder mysteries, featuring an erstwhile female reporter sniffing out intrigue in small Florida towns....The daughter of well-known comic strip artist Leslie Turner, Cook taught literature and writing in Tampa schools for 26 years and raised four children. Since retiring in 1989, she has published two novels regionally, with a third in the works. But Cook will no doubt always be best known for her picture on the Gerber labels. Cook was about 4 months old in 1927 when family friend Dorothy Hope Smith sketched the image in charcoal. Using a neighbor's baby as a model wasn't so unusual in the artist enclave of Westport, Conn. , and nobody thought much about it. Least of all Cook's dad, who for 27 years wrote and drew "Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy," a daily comic strip that ran in 500 newspapers. The next year, Gerber put out the call for images that could be used in ads for its new baby food products, and Smith submitted the drawing. "She wrote me [later] that she had thought it was kind of unfinished, and if they liked it she could finish it properly," Cook said of the sketch. "But they were smart enough that they didn't want anything done to it." Her likeness started appearing on the products in 1928 and became the official trademark in 1931."

, and nobody thought much about it. Least of all Cook's dad, who for 27 years wrote and drew "Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy," a daily comic strip that ran in 500 newspapers. The next year, Gerber put out the call for images that could be used in ads for its new baby food products, and Smith submitted the drawing. "She wrote me [later] that she had thought it was kind of unfinished, and if they liked it she could finish it properly," Cook said of the sketch. "But they were smart enough that they didn't want anything done to it." Her likeness started appearing on the products in 1928 and became the official trademark in 1931."

---"The Baby of Gerber's Family; for 75 Years, Ann Turner Cook Has Enjoyed Her Sketch of Fame," Mitch Stacy, Washington Post, February 29, 2004 (p. D1)

Recommended reading

- Encyclopedia of Consumer Brands, Volume 1: Consumable Products/Janice Jorgensen, editor

- Advertising Age Encyclopedia of Advertising, John McDonough, editor

[1931] PABLUM/CANADA

[1960s, USA]

"Fixing formula for your infant will soon be quicker and easier than pouring a glass of milk for your preschooler. ..If your pediatrician approves, you will be able to buy ready-to-serve formula at your grocery or drug store in disposible glass bottles, marked with ounces. The formula is already sterilized, will keep unopened without refrigeration and need not be warmed before feeding. All you have to do is replace the bottle's cap with a sterilized-sized collar. The ready-bottled formula...is due for national distribution within a few months...A carton of four four-ounce bottles is priced at 75 cents; of size ounce bottles, 87 cents; of eight ounce size, 99 cents...The same ready-to-serve formula has been available in cans since 1962, but most be poured into sterilized bottles before feeding. Coming on the market soon is kit which makes it possible to attach a nipple to the metal can for quick feedings. A new manufacturing process had to be developed, however, before the formula could be preserved in the glass bottles without refrigeration. The last dozen years have seen major changes in the way infants in the United States are fed.

..If your pediatrician approves, you will be able to buy ready-to-serve formula at your grocery or drug store in disposible glass bottles, marked with ounces. The formula is already sterilized, will keep unopened without refrigeration and need not be warmed before feeding. All you have to do is replace the bottle's cap with a sterilized-sized collar. The ready-bottled formula...is due for national distribution within a few months...A carton of four four-ounce bottles is priced at 75 cents; of size ounce bottles, 87 cents; of eight ounce size, 99 cents...The same ready-to-serve formula has been available in cans since 1962, but most be poured into sterilized bottles before feeding. Coming on the market soon is kit which makes it possible to attach a nipple to the metal can for quick feedings. A new manufacturing process had to be developed, however, before the formula could be preserved in the glass bottles without refrigeration. The last dozen years have seen major changes in the way infants in the United States are fed. Only one mother in five now fixes the baby formul using the traditional evaporated milk mixed with carbohydrate modifiers, a mainstay of two-thirds of babies in 1952. Half of today's mothers now use a prepared infant formula, either a powder or liquid which is mixed with water, or the ready-serve formula poured from a can into sterilized bottles. The percentage has doubled in the last five years, was only 15 per cent in 1952. One baby in five, usually those past three or four months of age, gets whole cow's milk. Only one in 10 is breast fed, still the safest, most convenient and least expensive method of nourishing an infant. But even some breast-fed infants are ocasionally given formula as a supplement, or when the mother must be away from home at feeding time."

Only one mother in five now fixes the baby formul using the traditional evaporated milk mixed with carbohydrate modifiers, a mainstay of two-thirds of babies in 1952. Half of today's mothers now use a prepared infant formula, either a powder or liquid which is mixed with water, or the ready-serve formula poured from a can into sterilized bottles. The percentage has doubled in the last five years, was only 15 per cent in 1952. One baby in five, usually those past three or four months of age, gets whole cow's milk. Only one in 10 is breast fed, still the safest, most convenient and least expensive method of nourishing an infant. But even some breast-fed infants are ocasionally given formula as a supplement, or when the mother must be away from home at feeding time."

---"Feeding a Baby is Easier, But There Are Still Problems," Joan Beck, Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1964 (p. A2)

Pablum brand baby food

The *problem* with pablum is this is both a proprietary tradename with a patented formula AND a generic word used by many to describe any fortified grain-based baby cereal. Some people (who are not fond of such products) use the term to indicate any bland, porridge-type food.

Some people (who are not fond of such products) use the term to indicate any bland, porridge-type food.

Who developed Pablum?

"During the 1920s and 1930s, considerable time and effort were spent studying the science of artificial feeding. The scientific management of child-rearing in general - from food to behaviour advice - increased the professional role and authority of physicians in child care issues. Society seemed to welcome the scientific approach to infant feeding and food and bought products that advertised increased nutritional value for their children. In 1931, Pablum, an infant cereal containing necessary minerals and vitamins for children's health, became available in Canada and the United States. The food was heralded as an excellent cereal addition to the infant's diet and remains a popular infant food today. It was three Canadian doctors - Frederick Tisdall (1893-1949), Theodore Drake (1891-1959), and Alan Brown (1887-1960) - who developed Pablum at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. "

"

Source: here

USA Patent & manufacturing

Mead Johnson secured US trademark rights in 1932 and patent protection in 1935:

"Harry H. Engel, a developer of Pablum baby cereal, has died at the age of 82. Mr. Engel, one of three patent holders on Pablum, died Friday at Deaconess Hospital in Evansville. Mr. Engle worked 47 years for Mead Johnson & Company before retiring in 1967. Fourteen years after joining the company as a chemist, Mr. Engle helped develop Pablum, a soft, bland cereal for infants."

---"Harry H. Engel," New York Times, April 2, 1984 (p. D13)

[NOTE: Mr. Engel's patent is number 1,990,329, published February 5, 1935. The other people named in this patent are Lambert D. Johnson and Nathan F. True.]

Trademarks

According to the records of the US Patent & Trademark Organization, Pablum brand baby food was introduced to the American public by Mead Johnson June 4, 1932:

"Word Mark PABLUM Goods and Services (EXPIRED) IC 030. US 046. G & S: SPECIALLY PREPARED CEREAL FOOD CONSISTING OF A MIXTURE OF WHEAT MEAL, OATMEAL, AND YELLOW CORN MEAL, TO WHICH HAVE BEEN ADDED WHEAT EMBRYO, DRIED YEAST, POWDERED DEHYDRATED ALFALFA LEAF, AND POWDERED BEEF BONE PREPARED FOR HUMAN USE. FIRST USE: 19320604. FIRST USE IN COMMERCE: 19320604 Mark Drawing Code (1) TYPED DRAWING Serial Number 71327942 Filing Date June 13, 1932 Current Filing Basis 1A Original Filing Basis 1A Registration Number 0297897 Registration Date October 4, 1932 Owner (REGISTRANT) MEAD JOHNSON & COMPANY CORPORATION INDIANA OHIO STREET AND SAINT JOSEPH AVENUE EVANSVILLE INDIANA Assignment Recorded ASSIGNMENT RECORDED Type of Mark TRADEMARK Register PRINCIPAL Renewal 2ND RENEWAL 19721004 Live/Dead Indicator DEAD"

US 046. G & S: SPECIALLY PREPARED CEREAL FOOD CONSISTING OF A MIXTURE OF WHEAT MEAL, OATMEAL, AND YELLOW CORN MEAL, TO WHICH HAVE BEEN ADDED WHEAT EMBRYO, DRIED YEAST, POWDERED DEHYDRATED ALFALFA LEAF, AND POWDERED BEEF BONE PREPARED FOR HUMAN USE. FIRST USE: 19320604. FIRST USE IN COMMERCE: 19320604 Mark Drawing Code (1) TYPED DRAWING Serial Number 71327942 Filing Date June 13, 1932 Current Filing Basis 1A Original Filing Basis 1A Registration Number 0297897 Registration Date October 4, 1932 Owner (REGISTRANT) MEAD JOHNSON & COMPANY CORPORATION INDIANA OHIO STREET AND SAINT JOSEPH AVENUE EVANSVILLE INDIANA Assignment Recorded ASSIGNMENT RECORDED Type of Mark TRADEMARK Register PRINCIPAL Renewal 2ND RENEWAL 19721004 Live/Dead Indicator DEAD"

The US Patent & Trademark Office confirms Pablum brand baby foods were abandoned by Mead Johnson March 18, 1997. This indicates the company is no longer manufacturing a product with this name. The only "live" mark for Pablum in this database his held by private individual.

"Word Mark PABLUM Goods and Services (ABANDONED) IC 005. US 018 046. G & S: precooked, dried cereals specially prepared for infants and children Mark Drawing Code (3) DESIGN PLUS WORDS, LETTERS, AND/OR NUMBERS Design Search Code 26.03.21 - Ovals that are completely or partially shaded Serial Number 74579245 Filing Date September 23, 1994 Current Filing Basis 1B Original Filing Basis 1B Published for Opposition June 25, 1996 Owner (APPLICANT) MEAD JOHNSON & COMPANY CORPORATION DELAWARE 2400 West Lloyd Expressway Evansville INDIANA 477210001 Assignment Recorded ASSIGNMENT RECORDED Attorney of Record Clark W. Lackert Description of Mark The drawing is lined for the color red. Type of Mark TRADEMARK Register PRINCIPAL Live/Dead Indicator DEAD Abandonment Date March 18, 1997

How was this product initially received?

"Competition from cheaper infoant food products has been growing, but the quality of Mead-Johnson's products and the goodwill of the medical profession which has been painstakingly developed and retained, places the company in a position from which it cannot easily be dislodged. Some new items, notably 'Pablum' cereal, recently added to the well-known line of specialty food products, have been well received."

Some new items, notably 'Pablum' cereal, recently added to the well-known line of specialty food products, have been well received."

---"Inquiring Investor," Wall Street Journal, April 12, 1934 (p. 8)

FoodTimeline library owns 2300+ books, hundreds of 20th century USA food company brochures, & dozens of vintage magazines (Good Housekeeping, American Cookery, Ladies Home Journal &c.) We also have ready access to historic magazine, newspaper & academic databases. Service is free and welcomes everyone. Have questions? Ask!

About culinary research & about copyright

Research conducted by Lynne Olver, editor The Food Timeline. About this site.

http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodbaby.html

© Lynne Olver 2004

3 January 2015

The history of baby food: how products for artificial feeding of children appeared

29 Apr 6 9601

Vadim Erlikhman, archivist, historian: Today, the fast food market is the fastest growing in the food industry. It is hard to believe that even a century and a half ago the very idea of feeding babies with something other than mother's milk seemed wild.

It is hard to believe that even a century and a half ago the very idea of feeding babies with something other than mother's milk seemed wild.

It is worth recalling that, of course, there were no maternity leave in the old days. A week after giving birth, peasant women had to work in the field, maids - to scrub the floor, factory workers - to go to the machine. In addition, there was a belief that before the baptism of the child, the mother should not breastfeed him. At that time, the child remained in the care of relatives, who instead of milk gave him "zhevka" - a rag with chewed bread or porridge. Sometimes it was soaked in milk, vegetable oil or sugar water. The rich had their own problems: feeding spoiled the shape of the breast, especially for mothers with many children. If a wealthy lady decided to feed the child herself, it was considered - depending on the fashion - either a feat or a strange quirk. Usually, a nurse was hired for this purpose, since there were enough young healthy women with an excess of milk.

The reason for this excess was not joyful: the huge infant mortality rate, which in the 18th century reached 40%. The main reason for this was the complete lack of hygiene: in Russian villages, in addition to a dirty rag, children were stuffed into their mouths with other rubbish, like a cut off cow's nipple. It was put on a horn, into which the same soaked bread or oatmeal was charged. Russian doctors wrote that in some provinces it was customary, along with the nipple, to give children wort, mash from the very first days. French peasant women, in order for their children to fall asleep better, gave them diluted wine to drink. Yes, and the nurses themselves drank wine and beer, it was believed that this adds milk. In one of Dickens' novels, a young mother drinks four glasses of port wine at dinner "under the pretext that she is breastfeeding."

In most cultures, breastfeeding continued for up to 6 months, after which the child was switched to solid food. Sometimes this was celebrated with a solemn ritual like the Indian “annaprashana”, when the eldest member of the family blessed rice porridge with sugar, tasted it and gave it to the baby. In China, children were accustomed to normal food in stages: first, liquid rice porridge (sifan), then boiled vegetables, tofu, and fish. In Africa, the first solid food for babies was corn porridge. In ancient Greece, it was a liquid barley stew, to which bull's blood was added in Sparta so that the boy would grow up to be a real warrior.

In China, children were accustomed to normal food in stages: first, liquid rice porridge (sifan), then boiled vegetables, tofu, and fish. In Africa, the first solid food for babies was corn porridge. In ancient Greece, it was a liquid barley stew, to which bull's blood was added in Sparta so that the boy would grow up to be a real warrior.

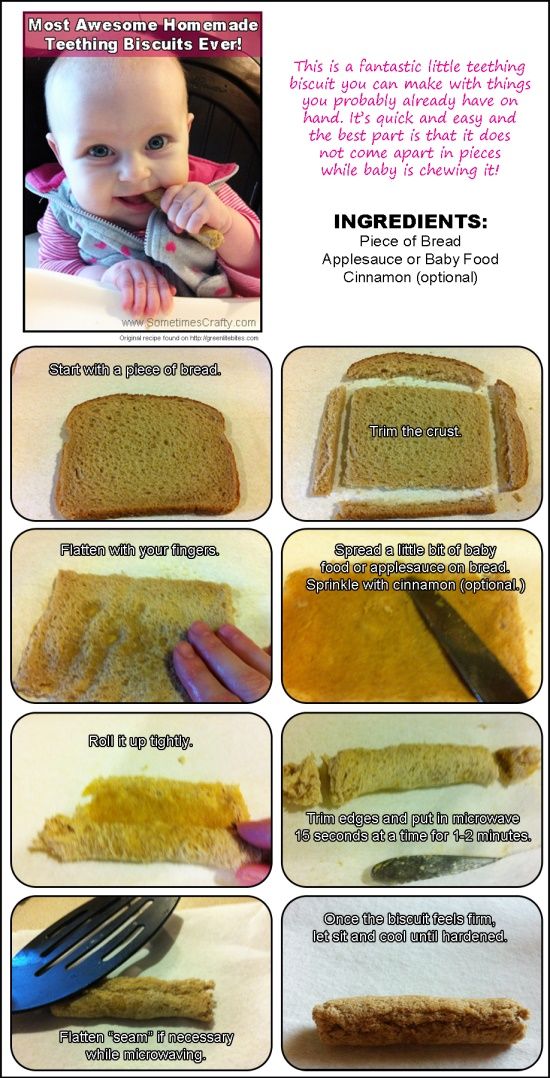

When children were teething, they were fed just like adults, only worse, because they were of no use. And this applied not only to poor peasants: Elizaveta Vodovozova recalls her childhood in a large landowner family in the middle of the 19th century: “Children were given everything that was worse and could not be used by adults ... Every pot of spoiled jam or marinade was shown to mother by the nanny. Having tasted one or the other, mother sighed heavily and said something like this: “What a misfortune! Really, it's no good. Well, let's go to the children. ”And in order to prolong our pleasure, and not because we could get sick from spoiled food, she told us to give us a small saucer. ”

”

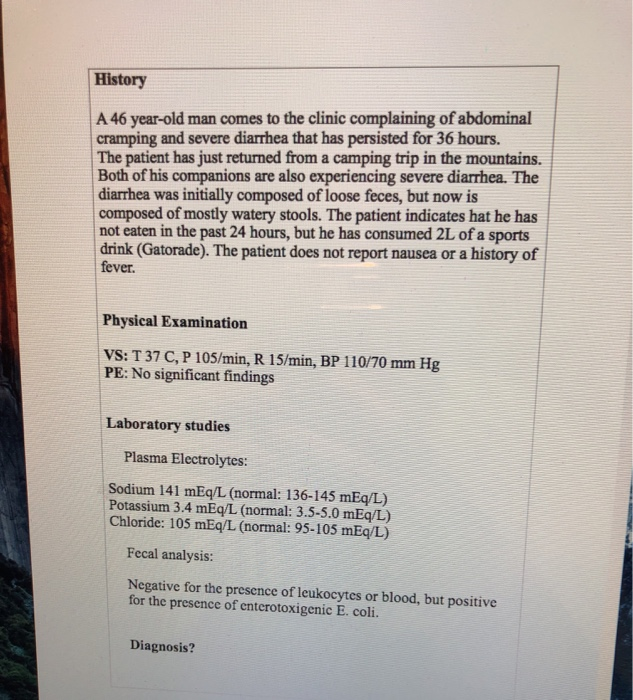

Doctors learned to cope with indigestion in children, but the lack of mother's milk became an increasingly serious problem. In big cities, the intense rhythm of life, air pollution, constant stress led to the fact that 30% of women did not have enough milk to feed a child, especially if he was the first or, conversely, the fourth or fifth. In families that could not afford to hire a wet nurse, babies were fed cow's or goat's milk. However, in composition it was very different from breast milk, so it often caused indigestion. There was also the problem of hygiene, because of which the German doctor Biedert warned: “It is necessary to observe pedantic purity both in keeping cows and in milking and preserving milk ... Since milk can acquire harmful properties from inappropriate food, cows should not be given even bards, no waste, because the toxic substances contained in them pass into milk and cannot be eliminated. ”There were also problems with the nurses, because they suffered from all kinds of diseases, up to syphilis, which were often transmitted to the child during feeding.

All this made scientists work hard to find a substitute for breast milk. Gradually, the necessary conditions for this arose: they learned how to preserve and disinfect products, and in 1855 the Englishman Grimweid began to make powdered milk. But if it were not for the son of the Frankfurt glazier Heinrich Nestle, who preferred to call himself Henri in French, all these discoveries might have existed on their own. The problem of baby food arose before Nestlé after the birth of his first child. A certified pharmacist who ran a pharmacy in the small Swiss town of Vevey, in 1867 made a mixture of powdered cow's milk, wheat flour and sugar, which he called "Henri Nestlé Milk Flour". Diluted with water, this mixture turned into the world's first artificial baby food.

According to legend, the first artificially fed baby was a premature baby of one of the local factory workers, who, of course, thanks to the Nestle formula, began to grow by leaps and bounds. The delighted pharmacist opened his own company, whose logo was a nest with chicks, because Nestle in German means "nest". Very soon, canned "milk flour" appeared in all European capitals. In 1872, it began to be sold in St. Petersburg, where a local merchant Alexander Wenzel became an agent of the Nestle company. He also sold other baby products, such as Maltos-Cannabis sugared hempseed extract, which was advertised as the best way to get a good night's sleep…

Very soon, canned "milk flour" appeared in all European capitals. In 1872, it began to be sold in St. Petersburg, where a local merchant Alexander Wenzel became an agent of the Nestle company. He also sold other baby products, such as Maltos-Cannabis sugared hempseed extract, which was advertised as the best way to get a good night's sleep…

In Russia, baby food did not take root at that time, but in Europe its popularity grew rapidly. Feeding babies has become unprecedentedly simple - open a jar and dilute its contents in water. However, even then doctors warned about the dangers of this simplicity. The German physician Gottfried Kühner wrote: “As for mealy surrogates, such as Nestle, Gerbera, Kufeke, Hartenstein’s leguminous powder, rakout, arrowroot, avicen, maizena, avena, etc., the same thing must be said about all of them: they are in many cases are well tolerated by children, but only after the second or third month of life. Violation of this condition, as well as the rules of hygiene, led to the fact that in 189In Berlin, infants fed formula were 13 times more likely to die than breastfed infants in Berlin in 1999.

The already mentioned Dr. Biedert noted: “The mass of artificial surrogates is not yet able to replace breast milk. Moreover, many of them, which came into use solely thanks to numerous and loud advertisements, should be recognized as directly harmful. At the same time, many considered the Nestle mixture to be the best: both milk and flour for it were made in the environmentally friendly conditions of the Swiss Alps. In the mid-1870s, the company launched another new product on the market - condensed milk. Although it was invented back in 1856 by American Gail Borden, it was Nestlé that made it a popular children's treat. True, the doctors were again unhappy: no one followed the recommendation to dilute condensed milk with water in a ratio of 1 to 10 and only then give it to children. Children fed with condensed milk became fat, anemic and sickly. Henri Nestlé sold the company in 1874. After 140 years, the profit of the largest food producer has reached almost 8 billion euros

Competitors were stepping on the heels of Nestlé more and more actively. In 1896, the Dutchman Martinus van der Hagen invented his own way of drying milk in a bakery. With significantly less flour and sugar, his milk formula quickly gained popularity, laying the foundation for Nutricia's international prosperity. In the US, baby food was taken over by Clapp's Baby Food and Beech-Nut, and Pablum was the first to sell cereal for children. However, it was Daniel Gerber, a cannery manufacturer from Fremont, Michigan, who gave the real scope to the case. The reason for this was again personal: Sally. the sick daughter of Daniel and his wife, Dorothy, required special nutrition. Having learned how to make mashed vegetables, fruits and meat, Dorothy suggested that her husband start mass-producing it. The advice turned out to be successful, and at 1928 year baby food company "Gerber Products" went on sale.

In 1896, the Dutchman Martinus van der Hagen invented his own way of drying milk in a bakery. With significantly less flour and sugar, his milk formula quickly gained popularity, laying the foundation for Nutricia's international prosperity. In the US, baby food was taken over by Clapp's Baby Food and Beech-Nut, and Pablum was the first to sell cereal for children. However, it was Daniel Gerber, a cannery manufacturer from Fremont, Michigan, who gave the real scope to the case. The reason for this was again personal: Sally. the sick daughter of Daniel and his wife, Dorothy, required special nutrition. Having learned how to make mashed vegetables, fruits and meat, Dorothy suggested that her husband start mass-producing it. The advice turned out to be successful, and at 1928 year baby food company "Gerber Products" went on sale.

Its popularity was ensured not so much by new products - they were successfully fed to children before, but by a purely American advertising scope. Immediately after entering the market, the company announced a competition for the best advertising, which was won by the artist Dorothy Hope, who painted a portrait of her neighbors little daughter. This Gerber baby has been sold all over the country, appearing in magazines beloved by housewives and on billboards. The brainchild of the Gerber spouses flourished even during the years of the Great Depression - after all, then the children needed even more artificial feeding. The company is still one of the three largest baby food manufacturers in the world, along with Nestle and Heinz, also known for its ketchup. And in the US, where baby food is consumed the most, Gerber even occupies 70% of the market.

This Gerber baby has been sold all over the country, appearing in magazines beloved by housewives and on billboards. The brainchild of the Gerber spouses flourished even during the years of the Great Depression - after all, then the children needed even more artificial feeding. The company is still one of the three largest baby food manufacturers in the world, along with Nestle and Heinz, also known for its ketchup. And in the US, where baby food is consumed the most, Gerber even occupies 70% of the market.

The Soviet Union lagged far behind in this area. Own baby food was not produced here for a long time. The elite could use the products of Nestlé and other Western companies, which were bought for foreign currency. For everyone else, there were dairy kitchens that had been open all over the country as far back as the 1920s. There, milk mixtures, fermented milk products, cottage cheese, juices, mashed fruits and vegetables were made from fresh products. Such kitchens were very useful: the children attached to them received good nutrition even during the years of famine and war. At 19In the 1950s, mass production of baby food began in the country: canned juices and purees, powdered milk mixtures, cereals and kissels. Twenty years later, in Istra, Voronezh, Novosibirsk, near Moscow, and then in other cities, factories were built that produce liquid mixtures for children, first in glass and then in cardboard containers. Now dairy kitchens did not prepare food, but gave out ready-made jars or bags.

At 19In the 1950s, mass production of baby food began in the country: canned juices and purees, powdered milk mixtures, cereals and kissels. Twenty years later, in Istra, Voronezh, Novosibirsk, near Moscow, and then in other cities, factories were built that produce liquid mixtures for children, first in glass and then in cardboard containers. Now dairy kitchens did not prepare food, but gave out ready-made jars or bags.

in the 1990s, our market was flooded with all the abundance of world baby products - milk formulas, kefir, yogurt, cereals. All this is sold in dry, liquid or frozen form and is certainly advertised as the most delicious and healthy food for children. In the competitive struggle, numerous companies adapt to different categories of consumers. For milk intolerant children, especially in East Asia, lactose-free formulas are made, where whey is replaced by no less nutritious soy protein. In New Zealand, Bibikol has developed infant formula from New Zealand goat milk, which they say differs in composition from goat milk common in Europe.

Whereas earlier they tried to expel any microorganisms from products for children, today useful bifidobacteria are specially bred in them. Baby food has become so widespread that not only children use it. Hollywood stars go on a diet of puree and milk for other reasons: baby foods are so nutritious that even small portions of them allow you to fill up and not get fat. Products for astronauts were also created at one time on the basis of baby food. Some firms tried to reverse the operation, but when the “space” tubes fell into the hands of the kids, their contents were squeezed out anywhere but into the mouth.

Children are special clients. To please them, the food must be not only healthy and tasty, but also bright, which is what producers use to make porridge or mashed potatoes red, orange or green. Sometimes this led to sad consequences. In the 1970s, a scandal erupted in the United States when a major company dyed a strawberry-flavoured children's breakfast cereal with an artificial dye that caused nausea. Thousands of parents called an ambulance - there was a complete impression that the children were vomiting blood. But the biggest scandal arose in the same 70s around the famous Nestle company - it was accused of killing many babies in "third world countries", in which, due to living conditions, mothers could not use the product correctly, they mixed food with dirty water or pour the mixture into unsterilized bottles. According to UNICEF, an unhygienic artificially fed infant is at least 6 times more likely to die from diarrhea alone than a breastfed infant.

Thousands of parents called an ambulance - there was a complete impression that the children were vomiting blood. But the biggest scandal arose in the same 70s around the famous Nestle company - it was accused of killing many babies in "third world countries", in which, due to living conditions, mothers could not use the product correctly, they mixed food with dirty water or pour the mixture into unsterilized bottles. According to UNICEF, an unhygienic artificially fed infant is at least 6 times more likely to die from diarrhea alone than a breastfed infant.

When a mother feeds her baby, she gives him not only nutrients, but also immunity to many diseases, and, no less important, strengthens the psychological bond with him. Speaking against artificial nutrition, activists from different countries created the World Alliance for Breastfeeding. Under his pressure, the World Health Organization in 1981 adopted the "Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes", adopted over time by all major manufacturers. It stated that companies should limit advertising and conduct sales of their products with the mandatory participation of medical professionals. True, this applies only to milk formulas, but other types of baby food are under close public scrutiny.

It stated that companies should limit advertising and conduct sales of their products with the mandatory participation of medical professionals. True, this applies only to milk formulas, but other types of baby food are under close public scrutiny.

IN THE MIDDLE AGES, CHILDREN'S FEEDING BOTTLES were made of leather and wood. At the beginning of the 19th century, porcelain bottles began to be produced. They wore nipples made of leather or suede.

The glass feeding bottle was patented in 1841 by Charles Windshiel of Massachusetts.

In 1981, the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes was created to control unacceptable marketing practices. The Code was developed by WHO/UNICEF. The official author of the code is IBFAN - International Active Baby Food Network. The code was approved by the World Health Assembly by a vote of 118 votes in favor, against 1 (the US refused to sign the code). A few years later, the rubber nipple was patented, and Windshield bottles were distributed worldwide. Mothers liked them very much. Such a bottle with an attached straw could be placed next to the child, and he could eat on his own. In the early 20th century, the Windshield bottle was banned. Rubber hoses clogged and became breeding grounds for bacteria.

Mothers liked them very much. Such a bottle with an attached straw could be placed next to the child, and he could eat on his own. In the early 20th century, the Windshield bottle was banned. Rubber hoses clogged and became breeding grounds for bacteria.

International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes

The Code is addressed to governments and infant formula companies. It is a concise guide to the marketing of breast milk substitutes. Its main task is to protect the lives of children by providing them with the best food - breast milk.

Products covered by the code include:

- artificial baby milk

- other artificial milks

- all types of baby food: juices, purees, soups, pates, etc.

- Feeding bottles and teats.

The Code contains the following guidelines:

- Information or educational materials, equipment or products may be distributed free of charge only with the written permission of the relevant authorities.

(Company logo may appear but product brand may not)

(Company logo may appear but product brand may not) - No company materials may be distributed to mothers.

- Health workers should support breastfeeding and encourage mothers to choose to breastfeed. They should help promote the principles of this code.

- Do not use the health system to market artificial breast milk.

- Health system display media such as posters, booklets, flyers, brochures, feeding bottles, labels, prescription forms, and other artificial nutrition promotional materials may not be used.

- Representatives of manufacturing companies should not work in the health care system, in the field of child care and should not be in contact with mothers.

- Demonstration of artificial feeding techniques may only be conducted by health workers in families where there is an absolute medical indication for supplementary feeding. At the same time, information about the risk to the health of the child if the product is used incorrectly must be provided.

- Artificial milk may not be distributed free of charge or at reduced prices in the health care system. Donations in the form of artificial milk, feeding bottles and other products can only be given to orphanages and similar institutions, but not to hospitals and maternity hospitals.

- Hospitals and maternity hospitals should buy this formula just like everyone else.

- All information provided by health care professional firms must be limited to scientific facts and must not suggest that formula feeding is identical or superior to natural feeding.

- Promotion of products by healthcare workers, as well as their material and financial incentives, is not allowed.

- Health workers should not distribute artificial milk samples to pregnant women, mothers of infants and young children, or their family members.

Summary of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes

- No advertising of these products to the public!

- No free samples for mothers

- No health promotion for this product, including free or cheap baby food.

- No company representatives to contact mothers.

- No gifts or samples for healthcare workers. Health care workers should never give these products to mothers.

- No distribution of texts or graphic products idealizing formula feeding, including pictures of infants on labels.

- Information provided by healthcare professionals must be scientific and relevant.

- All information on bottle feeding should explain the benefits of breastfeeding and the costs and dangers associated with bottle feeding.

- Unacceptable products such as condensed milk must not be advertised as baby food.

- Manufacturers and distributors must act in accordance with the terms of the code, even if their countries have not committed themselves to comply with the terms of the code.

See also: webinar by Irina Ryukhova Introduction to motherhood

Irina Ryukhova's webinar series Breastfeeding. Fundamentals”

Fundamentals”

В Olga Evtukh’s ebinar “The introduction of natural complementary foods”

Based on the materials of the Gala Biography magazine (04.2015)

9000 The most detailed historical excursion! Breastfeeding has always been regarded as the preferred choice. If there was not enough mother's milk or the mother could not feed the child for some reason, the family hired a nurse and left her in their home or gave the child to the nurse's family for the entire period of breastfeeding. This practice was common in Europe, America and Russia.

The nurse was chosen with particular care, as there was a strong belief that the quality of breast milk was of decisive importance for the health and behavior of the child. Brunette nurses were preferred to blonde and red-haired nurses: for some reason it was believed that their milk was more nutritious and balanced.

During the 18th century in Europe, the need for nurses was so great that there were special bureaus where nurses were registered . The activities of such bureaus were strictly regulated by laws. Thus, nurses had to undergo a medical examination and they were strictly forbidden to breastfeed more than one baby at the same time.

The activities of such bureaus were strictly regulated by laws. Thus, nurses had to undergo a medical examination and they were strictly forbidden to breastfeed more than one baby at the same time.

In the XIX century. wet nurses lost popularity, attention turned to the search for an adequate substitute for human milk from goats, cows, mares and donkeys. The practice of feeding cow's milk was the most common due to availability. However, it was believed that donkey's milk is more preferable, since it looks more like a woman's in appearance. Doctors' prescriptions were not unambiguous - some of them advised to use only freshly milked milk, others recommended heating or even boiling milk before feeding, others - diluting milk with water and adding sugar or honey.

At first, a cow's horn with a drilled hole was used for feeding, into which a piece of suede was inserted as a nipple. The Industrial Revolution offered a functional alternative to the horn - vessels made of metal, glass or ceramics. They had two holes on opposite sides - one was closed with a cork stopper, and the other was used as a nipple.

They had two holes on opposite sides - one was closed with a cork stopper, and the other was used as a nipple.

Another popular design was similar to the long handled teaspoon, the edge of the spoon was shaped like a nipple . The openings of the nipples were sealed with chamois, parchment or sponge. The rubber nipple was invented in 1845 by the American E. Pratt and quickly gained popularity.

After milk, the next food for infants was porridge, consisting of boiled milk or water mixed with flour and sometimes egg yolk. An improved form of baby food was the so-called panada - bread crumb boiled in milk or broth or crushed cereal grains .

For a long time, the goal of nutritionists and pediatricians has been to find an adequate and safe replacement for human milk. Already at the beginning of the XIX century. there is compelling evidence in the increased mortality rate of infants fed whole cow's milk, and that this almost always leads to indigestion and dehydration. In 1838, the German scientist Johann Franz Simon published the first comparative chemical analysis of human and cow's milk. This data has been in the development of formulas for artificial feeding for several decades.

In 1838, the German scientist Johann Franz Simon published the first comparative chemical analysis of human and cow's milk. This data has been in the development of formulas for artificial feeding for several decades.

I.Simon discovered that cow's milk has a higher concentration of protein, but less carbohydrates than women's milk . In addition, he suggested that the denser casein clot of cow's milk leads to digestive problems. In this regard, doctors began to recommend adding water, sugar, cream to cow's milk in order to adjust the composition of milk and bring it closer to women's.

In 1860, German chemist Justus van Liebig developed the first commercial formula for powdered infant formula. It was composed of wheat flour, whole milk powder, malt powder and potassium bicarbonate. Very quickly, "Liebig's powder" became available and popular in Europe - it was added in a certain proportion to warmed milk immediately before feeding. In the USA "Liebig's powder" appeared on the market in 1869. It could be bought at grocers for a dollar a pack.

It could be bought at grocers for a dollar a pack.

In 1870, Nestlé baby food powder made from malt, whole milk powder, sugar and wheat flour was sold in Europe and the USA. In the US it was offered at 50 cents per pack. Unlike Liebig's powder, Nestlé's product was reconstituted with drinking water, not milk, and can therefore be considered the first ever artificial milk formula for baby food.

After 20 years, several more baby formulas appeared on the market. By 1897, there were at least 8 brands listed in the Sears specialized catalog, such as Horlick malt nutrition, Mellin and Ridge infant formulas. Despite being widely used, formulas were sold in very limited quantities, as they were several times more expensive than cow's milk.

At the end of the 19th century many practicing pediatricians expressed confidence that the composition of the infant formula should be calculated and prescribed not by the manufacturer, but by the doctor observing the baby. In addition, many of them were convinced that commercial formulas were inadequate in nutritional value and not suitable for infants.

In addition, many of them were convinced that commercial formulas were inadequate in nutritional value and not suitable for infants.

The American Thomas Morgan Rotch of Harvard proposed the so-called percentage method for calculating infant feeding rations, which has been extremely popular among professionals since 1890 to 1915. The formula calculated the exact proportions of cow's milk, water, cream and sugar. The pediatrician had to carefully monitor the weight gain and the consistency of the child's stool and, in accordance with their dynamics, modify the composition of the prepared mixture. However, by the 1920s, pediatricians found this method too difficult to perform and began recommending commercial powder formulas again.

At the turn of the 20th century, medicine came to realize that infectious diseases can be caused by food-borne pathogens. Perishable milk (before 1910, refrigeration equipment was not yet widely used), as it has been experimentally proven, can become a source of the spread of tuberculosis, typhoid, cholera and diphtheria.

In 1864, Louis Pasteur discovered that heating beer or wine to high temperatures kills the bacteria that normally cause the product to go sour. In 1890, the pasteurization process was also proposed for the dairy business, not to make milk a safer product, but to prevent it from going sour when transported by rail when unrefrigerated. A few years later, it was proven that pasteurization also protects against dangerous infections.