When do babies stop gagging on food

Feeding Development and Difficulties : Ava

-

Gagging or choking - Challenges increasing textures in the diet

- Development of oral motor skills enables children to manage foods with an increasing range of textures.

- Gagging is a reflex action that helps to prevent choking. It can be triggered by fingers, food, a spoon or toys touching the back of the mouth. The gag reflex diminishes at around 6 months of age coinciding with the age at which most babies are learning to eat solid foods. Some children have a hypersensitive gag reflex and will gag more easily.

- Gagging is a common response when infants are making the transition from smooth to lumpy foods or when learning to chew. It is best managed by providing graded food textures that support or match the development of oral motor skills. Exploring of the mouth with hands and toys and encouraging feeding independence helps with diminishing the gag reflex.

- With positive reinforcement gagging can become a learnt behaviour. To prevent this avoid overreacting to the child’s gagging response. Simply remove the piece of food and provide reassurance.

- Gagging is not the same as choking where the airway becomes blocked preventing breathing. Unlike gagging where the child will make retching noises choking is silent. Babies and young children should always be supervised when eating.

Case scenario

Ava aged 14 months is referred for assistance with feeding. Her parents are concerned that Ava has a swallowing problem as she will only eat smooth puree foods. If she is given any lumps in her food she will gag and usually vomit.

Remember to consider your own response before viewing suggested answers.

Question 1

What are the key elements of your assessment of Ava’s feeding difficulty?

Key elements of your assessment include:

- Parent’s perception of the problem.

- Medical, developmental, growth and social history.

- Dietary assessment.

- Observation of feeding.

Your assessment reveals the following details:

Parent’s perception of the problem

- Ava’s parents report, “Ava started solids when she was almost 6 months old. She seemed ready. She was very interested in watching her sisters eat. However she didn’t really seem to enjoy the foods I gave her. She would spit a lot out. She liked the commercial baby foods better than the foods we made for her. They seem smoother and she managed them better.”

- “When I tried her on the next stage foods with the lumps but she gagged and looked like she was about to choke.”

- “We waited a while before trying again but she still gags on the

tiniest lumps. It is getting worse and now she vomits if she finds a

lump. We are sure she has a swallowing problem.

”

”

Medical, Developmental, Growth and Social History

- Ava was born at term. There are no concerns regarding her development and her growth has tracked consistently around the 25th percentile. She has not had any significant illnesses.

- Ava lives with both her parents. Mum does not work and is the primary carer for Ava and her two older sisters. Dad is employed full time.

Dietary assessment

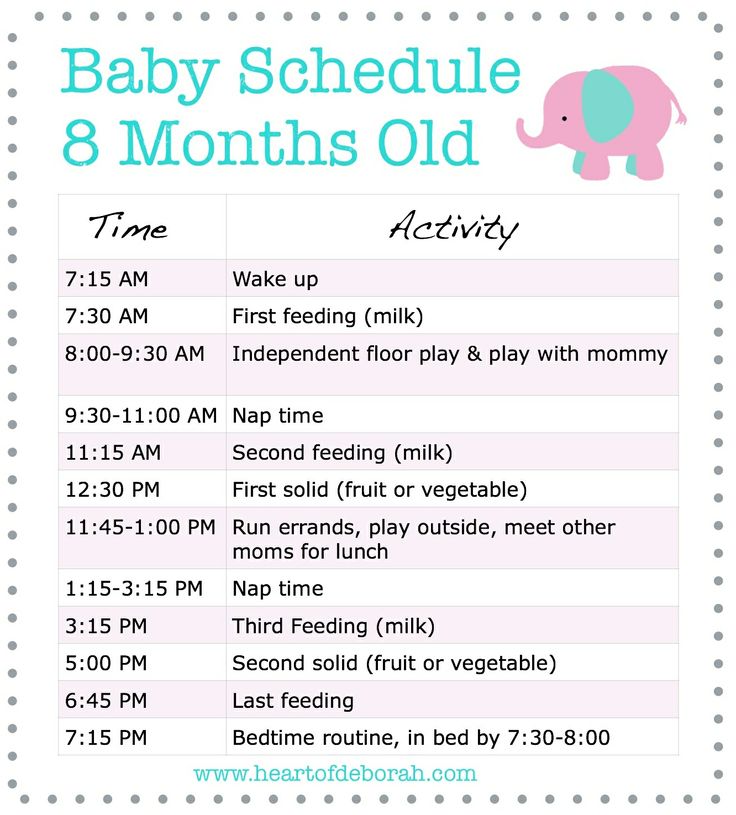

- Ava has smooth infant cereal for breakfast. Lunch and dinner typically consists of smooth commercially prepared foods that include meat and vegetables. This is usually followed by puree fruit with yoghurt or custard. She is either fed by mum using a spoon or self feeds by sucking food directly from the ‘pouch’.

- Sometimes Ava will mouth toast or biscuits until they go soggy but she doesn’t appear to swallow any.

- Ava was breast-fed until around 10 months of age.

She then

commenced infant formula and is currently having 3 small bottles per

day. She also has water from a cup.

She then

commenced infant formula and is currently having 3 small bottles per

day. She also has water from a cup.

Mealtime Observation

- Ava is well supported in a high chair.

- She is offered lunch as described above. She is observed to be happy and interactive when being spoon fed and enjoys the independence of feeding herself from the pouch.

- Mum agrees to offer Ava some fork mashed fruit so that the observer can make an assessment of Ava’s response.

- As mum predicts Ava gags and vomits. The observer notes that mum fusses over Ava when she gags. She has a bowl ready at the table to ‘catch the vomit’ and prevent a mess.

- It appears that mum has a low tolerance for mess as Ava is also not encouraged to use a spoon to self-feed.

Next Question

Babies Gagging vs.

Choking When Starting SolidsAdie, 12 months, gags on a small piece of bread.

Choking When Starting SolidsAdie, 12 months, gags on a small piece of bread.What is gagging?

Gagging is a natural protective reflex that results in the contraction of the back of the throat to protect us from choking. Just like the reflexive kick that occurs when the doctor taps your knee in just the right spot, the gag happens automatically, initiating a rhythmic bottom-up contraction of your pharynx (the tube that leads to your stomach) to assist in bringing food up and to stop the swallowing reflex from making our bodies try to swallow.

>> Just starting solids? Check out our virtual course (includes videos on infant rescue) as well as our guides and recipes on for the best first foods for baby. And if you are struggling with the transition from spoon feeding / purees to self-feeding with table food, watch our Spoons to Fingers video.

This page has been created with typically developing infants and children in mind. The information here is generalized for a broad audience and is for informational purposes only. If your child has underlying medical or developmental differences, including but not limited to prematurity, developmental delay, hypotonia, airway differences, chromosomal abnormalities, craniofacial anomalies, gastrointestinal differences, cardiopulmonary disease, or neurological differences, we strongly recommend you discuss your child’s feeding plan with the child’s doctor, health care provider or therapy team. The opinions, advice, suggestions and information presented in this article on gagging are for informational purposes only and are not a substitute for professional advice from or consultation with your pediatric medical or health professional. If your child is having a health emergency, please call 911 or your emergency medical resource provider immediately.

If your child has underlying medical or developmental differences, including but not limited to prematurity, developmental delay, hypotonia, airway differences, chromosomal abnormalities, craniofacial anomalies, gastrointestinal differences, cardiopulmonary disease, or neurological differences, we strongly recommend you discuss your child’s feeding plan with the child’s doctor, health care provider or therapy team. The opinions, advice, suggestions and information presented in this article on gagging are for informational purposes only and are not a substitute for professional advice from or consultation with your pediatric medical or health professional. If your child is having a health emergency, please call 911 or your emergency medical resource provider immediately.

Swallowing is a complex reflex with multiple lines of defense built in to prevent choking. These actions happen reflexively, meaning the brainstem tells our body to do them–they are involuntary. There are three important lines of defense that we have with every single swallow.

There are three important lines of defense that we have with every single swallow.

1. When we swallow, our vocal cords, which are like sliding doors inside the breathing tube, come together, closing off the airway and preventing food from entering the lungs.

2. The muscles of the throat pull the breathing tube slightly up and forward, tucking it safely out of the way of the food passing.

3. The epiglottis, a tiny flap of cartilage, tilts down to cover the airway forming a tight seal with the joints that help move the vocal cords.

Just like any good system, we have back up already built in. We even have back up for those back ups that are activated if needed. For example, if anything gets too close to the opening of the airway, even before it gets a chance to get in, the vocal cords immediately close (the technical name for this is the laryngeal adductor reflex), and our body immediately coughs to push the item away from the breathing tube. Our bodies are quite skilled at keeping us safe. 12

12

First, it is important to distinguish the difference between gagging and choking.

True choking is when the airway is obstructed, and the baby is having trouble breathing. Signs of a baby choking can include:

- inability to cry

- difficulty breathing

- skin tugging into the chest

- look of terror

- high-pitched sounds

- skin color changes (ranging from blue to purple to ashen-like)

If you suspect baby is choking, immediately administer infant choking first aid with alternating back blows and chest thrusts and call 9-1-1 or local emergency services on speakerphone so your hands are free. If another person is present, one person should immediately perform choking first aid while the other calls for help. Conduct age-appropriate CPR if you believe baby’s airway is open, but the child is not breathing.

On the other hand, gagging is a common protective reflex that results in the contraction of the back of the throat. It is a natural function and protects us from choking. When this happens, it’s important to let baby work the food forward on their own. Refrain from sticking your finger in baby’s mouth, which can push the object further down the throat, making the situation worse.

It is a natural function and protects us from choking. When this happens, it’s important to let baby work the food forward on their own. Refrain from sticking your finger in baby’s mouth, which can push the object further down the throat, making the situation worse.

We strongly recommend you take a CPR class online or at your local health facility and review safety procedures. Our choking, gagging & infant rescue video can also help you visualize the difference. Further resources:

- American Red Cross: Child & Baby CPR

- American Heart Association: Infant CPR Training Kits

- Harvard Health: Heimlich Maneuver on an Infant

Gagging is a completely normal reflex in infants, children and adults alike. Gagging is very common and will happen a lot in baby’s solid food journey. All babies gag in their eating journey—it’s one way they learn how to eat. The good news is that babies typically outgrow gagging after a couple of months of practice with various textured foods.

The good news is that babies typically outgrow gagging after a couple of months of practice with various textured foods.

Babies often gag well before they start solids, when breast or bottle feeding. This typically occurs when baby either isn’t properly latched, and the nipple triggers the reflex, or if the baby isn’t ready to swallow milk for whatever reason. Some babies gag when mom’s letdown is too fast. Others gag when they need to catch their breath instead of swallowing. Many babies will gag on a pacifier or certain bottle nipples if they aren’t familiar with them. All of these gags occur because the brain is trying to protect the baby from swallowing an “intruder,” or something the baby isn’t ready to swallow. This gag reflex typically lessens over the first few months of baby’s life when baby gets “desensitized” and learns to accept it (pacifier, nipple, or food texture) without gagging. This occasional gagging at a young age does not seem to bother most infants.

Interestingly, the gag reflex of a 6- to 10-month-old baby is much more sensitive and can be triggered more forward on the tongue than an adult.3 4 This is why babies gag easily: the more forward the gag trigger is on the tongue, the easier it is to trigger.5 It is not uncommon for babies to gag (and occasionally vomit) for the first few weeks of solids. If baby repeatedly gags and vomits past the first month of starting solids, consult your pediatrician, who may refer you to a swallowing specialist.

Watch our video on gagging and all of the other normal, sometimes nerve-wracking things babies do while starting solids.

Cooper, 6 months, gags on applesauce.Ronan, 7 months, gags on a flattened blueberry, spits up some, and carries on eating.Quentin, 8 months, gags and coughs on some bread with avocado. Bread is notorious for triggering gagging as it sticks to saliva on the tongue.Gagging helps prevent chokingWhen the gag reflex is triggered, it forces the back of the throat to close, essentially preventing swallowing. If food caused baby to gag, the reflex forces the food (or object) forward towards the front of the tongue. Young infants naturally open their lips when they gag, which means that typically, the food or object that caused the gag keeps moving out of the mouth.![]()

Gagging is completely normal and incredibly important for baby’s safety, both at the table and away from it.

Gagging helps babies learn to eatFor babies to build the skills for chewing and managing all foods (not just easy-to-chew foods), we need to give them opportunities to make mistakes, like taking a too-big bite of food. When a baby bites off too much food and cannot properly move it around to chew, the gag reflex will kick in and help thrust the food forward. The experience teaches baby that the food was too big to swallow. These experiences are essential for learning and building confidence in biting and tearing. Over time, baby will learn to take smaller bites and become more adept at moving food around to chew properly.

Once baby is a few weeks into their solid food journey, you can use the gag reflex to your advantage. Offer foods that are not as easy to chew to help advance baby’s oral development more quickly. When poorly chewed food touches the tongue, the gag reflex will do its job, and baby will learn they need to chew the food more.

It’s important to challenge baby before they get too accustomed to mashes and soft foods. Babies quickly learn that chewing and swallowing mashes and other easy-to-chew foods easily satisfies their hunger with minimal work. Many babies won’t bother trying to improve their skills with tough consistencies that require more biting and tearing, and may refuse the challenging foods and wait for the easier foods.

Hillis, 6 months, gags on a vegetable purée.Addie, 9 months, gags and coughs on asparagus and successfully moves it forward out of her mouth.Ysabella, 8 months, gags on purple dragon fruitWhy is my baby gagging? Gagging is easily triggeredWhen it comes to young babies, the gag reflex is pretty easy to trigger. Touch the middle of the tongue, and many babies will gag. If you watch a 3- to 4-month-old baby mouthing their hands and fingers, you will see them gagging themselves frequently. This is common and normal. Babies are typically not bothered by it and will often keep doing it.

Our mouths are one of the most sensitive parts of our bodies. The human mouth has many sensory receptors to detect touch, taste, temperature, pressure, and other input types. Babies are driven to explore with their mouths to learn about their world simply because the mouth is sensitive. Mouthing exploration could be very unsafe if babies didn’t have gagging as a natural safety net.

Importantly, young infants have immature hand and finger coordination, which means they can’t easily remove something they put in their mouth. They also have immature oral motor (tongue and mouth) coordination. They can’t easily use their tongue to find an object in their mouth and spit it out. This is another reason the gag reflex is a safety reflex, as it allows a baby to put an object in their mouth and then push it back out again without letting it get close to the throat. As babies put things in their mouth, the gag reflex tells them when things are not supposed to be there and prevents it from moving too far back towards the throat.

The gag reflex moves further back in the mouth as babies ageFrom birth to around 7-9 months, the gag reflex is triggered close to the front of the mouth (around the middle of the tongue). At this age, the gag reflex is as sensitive as it will ever be.6 This is important for safety because objects (food or anything else) will quickly trigger the gag reflex and be pushed out of the mouth before they get past the middle of the tongue.

Sometime around 7-12 months of age, the gag reflex slowly desensitizes. The gag trigger moves from the middle of the tongue to the back of the tongue towards the throat.7 At this point, food or objects can get much closer to the throat before the body recognizes something is too big to swallow and tries to push it back out. This might sound scary, but remember, our bodies are amazing! The gag reflex remains active and strong, so if something (food, barbie shoe, bug, etc.) hits the back of the tongue, the back of the palate (roof of the mouth), or even the back of the throat, the gag still kicks in.

Mahalia, 10 months, gags on some orange stuck to her tongue. If you look closely, you can see the orange isn’t actually all that far back in her mouth, but more on the middle of her tongue. She recovers nicely and carries on eating.Adie, 12 months, gags and coughs on a piece of bread. Bread sticks to the saliva on our tongues easily and can trigger the gag reflex a lot. As you see here, Adie recovers nicely and carries on eating.Babies gag on puréed food and jarred baby food, too

She recovers nicely and carries on eating.Adie, 12 months, gags and coughs on a piece of bread. Bread sticks to the saliva on our tongues easily and can trigger the gag reflex a lot. As you see here, Adie recovers nicely and carries on eating.Babies gag on puréed food and jarred baby food, tooThe threshold for what triggers a gag and the gag’s intensity is different in every baby, but most infants will go through a period where anything in their mouth thicker than breast milk or formula will cause a gag. The brain says: “Wait, this isn’t right! I shouldn’t swallow this! GAG!” Many will gag with spoon-feeding experiences even with runny, watery bland purées.

Until the special day you decide to start solids, baby hasn’t had to manage anything but a watery-thin, fast-moving liquid. Enter something slightly thicker, slippery, and a different flavor — baby’s brain will kick in with protective mechanisms to gag and prevent swallowing this invading purée. This is usually short-lived because thin purées are quite similar to liquids and the texture won’t trigger a gag for very long.

Enter something slightly thicker, slippery, and a different flavor — baby’s brain will kick in with protective mechanisms to gag and prevent swallowing this invading purée. This is usually short-lived because thin purées are quite similar to liquids and the texture won’t trigger a gag for very long.

Babies know to push the tongue against a breast or bottle nipple to initiate suction and move the liquid backward to their throat. Spoon-feeding can present unique oral-motor challenges. With a spoonful of purée dropped on the middle of the tongue, baby has nothing to suck or push against and doesn’t yet know the skills to help move that food backward. Because they can’t move the purée backward quickly, it either continues to sit on the middle of the tongue or will start spreading around the mouth, which can lead to gagging. Many wise babies will suck on the spoon to help them quickly move the purée back to swallow, just like they do from a bottle or breast. Those babies, who now have a way to control the purée, will often easily swallow with minimal or no gagging.

While not all babies who are spoon-fed gag, many do. Not surprisingly, when a baby is exclusively spoon-fed for a prolonged period of time (past 8 months of age, for example), that child may gag more when they start finger foods due to the lack of texture exposure.

Max, 4 months, gags on rice cereal.Levi, 6 months, gags on a vegetable purée. Jai, 6 months old, gags on a squash purée and mom (rightfully) asks her partner not to intervene. Spoon-fed babies gag less at first but gag more later

Spoon-fed babies gag less at first but gag more laterWhen a baby is started on solids with thin, watery purées and pouches, the baby’s tongue receives less sensory input. While babies gag on purées too, they acclimate to the smooth texture or figure out how to use the spoon to suck back and swallow, which reduces gagging. However, all babies will frequently go through gagging periods when introduced to finger foods — whether 6-month-olds or older spoon-fed babies. When baby is first offered finger foods, the brain engages the safety call: “This doesn’t seem right! I don’t know how to move this! We shouldn’t swallow this food!” Often, this period of gagging will last longer with babies who started with spoon-feeding.8

In 2016, the “BLISS” study found that babies who follow a spoon-feeding approach to solids (spoon feeding smooth purées > lumpy purées > finger foods) tend to gag less at 6 months but more at 8 months and later.9 Remember: around 8 months, a baby’s gag reflex becomes less sensitive and moves further in the back of the mouth. This means that food is closer to the throat before the body reacts and tries to push it out.10 In other words, waiting to introduce finger foods until after baby is 8 or 9 months old may increase the choking risk as the gag reflex is less sensitive, further back in the mouth, and baby is not accustomed to textures other than soft foods from a spoon.

This means that food is closer to the throat before the body reacts and tries to push it out.10 In other words, waiting to introduce finger foods until after baby is 8 or 9 months old may increase the choking risk as the gag reflex is less sensitive, further back in the mouth, and baby is not accustomed to textures other than soft foods from a spoon.

By 8-9 months old, a spoon-fed baby has been practicing a very specific skill to eat. “Purées come into my mouth. I suck or lift my tongue to move that puréed food backward, and I swallow it.” Babies will always start with the skill they know and try to use that same pattern on solid foods. They try to move that solid food straight back without the necessary step of moving the food laterally to their gums to chew. This motor pattern often leads to even more gagging.

The older the baby, the more aware they are of gagging and its unpleasantness. A 9-month-old baby is more aware of gagging than a 6-month-old baby. “Hebbian plasticity”—a fancy term that brain specialists use—tells us that neurons that fire together wire together. This means that when one part of the brain lights up simultaneously as another part of the brain, the brain starts to build a connection between those two areas. So, frequently gagging as the baby gets older and more aware of their body may be problematic for some babies who seem to draw a connection between real food and gagging. These babies seem to learn quickly that real food will make them gag and can lead to refusal of any food that is not a purée or mash. By contrast, younger infants don’t seem affected as much as older babies and toddlers.

“Hebbian plasticity”—a fancy term that brain specialists use—tells us that neurons that fire together wire together. This means that when one part of the brain lights up simultaneously as another part of the brain, the brain starts to build a connection between those two areas. So, frequently gagging as the baby gets older and more aware of their body may be problematic for some babies who seem to draw a connection between real food and gagging. These babies seem to learn quickly that real food will make them gag and can lead to refusal of any food that is not a purée or mash. By contrast, younger infants don’t seem affected as much as older babies and toddlers.

At 6 months old, the gag reflex is necessary to exploring food. It’s what allows a young baby with almost zero chewing skills to put a piece of food in their mouth and, if it is too big to swallow, get that food safely back out.

Infants learn how to do amazing things—sitting, crawling, walking, and running—by using reflexes, fumbling around, and making lots of mistakes while slowly building strength and adding one movement on top of another. The same applies when learning to chew—babies use reflexes coupled with fumbling as they learn.

The same applies when learning to chew—babies use reflexes coupled with fumbling as they learn.

Amazingly, babies have two other key reflexes—the biting reflex and the tongue lateralization reflex— which help them learn to chew right away at 6 months. For foods to be properly chewed, baby needs to:

- Take a bite.

- Move that food to the side (tongue lateralization).

- Munch up and down to break down the food down.

- Move the food back to the tongue for swallowing.

When babies first start finger food, they will struggle to use their biting and lateralization reflexes in any coordinated way. Simply put, they fumble around! As babies learn to eat, they won’t break down food enough to safely swallow, which requires the gag reflex to push the unchewed food back out. But every time baby does that, they are learning where the food is in their mouth. Slowly and incrementally, babies learn how to move food to different parts of their mouth. They learn their tongue can help push food around the mouth in lots of directions. They learn their palate, tongue, gums, and saliva will break the food down as it moves around their mouth. All of these actions turn a solid food into something like a mash!

They learn their tongue can help push food around the mouth in lots of directions. They learn their palate, tongue, gums, and saliva will break the food down as it moves around their mouth. All of these actions turn a solid food into something like a mash!

Some experts suggest that purees teach babies to swallow correctly, and gives practice swallowing solids before you introduce the idea of chewing. Most babies do not need to be taught how to swallow. Swallowing is a deep brainstem reflex present by 15 weeks gestation2 and well established by full term birth. Babies already know how to swallow; there is no need to practice! Interestingly enough, thicker textures are actually easier for babies to swallow (think purees), and our feeding therapists explain that babies who have swallowing difficulty are actually prescribed thickened milk to drink! But purees do teach baby a motor pattern: bring food in, move it back, swallow. This is a dangerous pattern because most solid foods require chewing before you move them back and can safely swallow. We believe that exclusive purees are time wasted because baby isn’t practicing chewing and is practicing a dangerous motor pattern that must be unlearned.

We believe that exclusive purees are time wasted because baby isn’t practicing chewing and is practicing a dangerous motor pattern that must be unlearned.

Interestingly, the BLISS study also demonstrated that infants who started solids with finger foods experienced more gagging at 6 months, but less gagging at 8-9 months as they developed more control and coordination in moving food around their mouth.11 This demonstrates that babies who are given the opportunity to work with finger foods early on in their solids journey—well before 8 months of age—develop the oral-motor skills required for mature eating more quickly than spoon-fed babies.

After a couple of months, most babies who start with finger foods at 6 months of age develop the skill and coordination to chew and move well-chewed food backward to swallow safely. The baby feels comfortable with their skills and is accustomed to food moving in this way. The body won’t initiate a gag so readily.

By contrast, babies who start solids with purées have had little chewing practice from 6-8 months. It’s likely they are less coordinated with moving food around their mouth, less able to break down the food, and less safe in the instance that the food gets pushed back further in the mouth than they can handle.

It’s likely they are less coordinated with moving food around their mouth, less able to break down the food, and less safe in the instance that the food gets pushed back further in the mouth than they can handle.

How to help baby move past gagging by building skill

How to help baby move past gagging by building skillSuccessful eating is not just about chewing but about feeling where the food is in the mouth and knowing if it’s chewed “enough” to swallow safely. As adults, most of us can identify and discretely spit out a tiny piece of bone or eggshell from a bite of food. Because this is happening inside the mouth, we aren’t using our eyes; our brains visualize what’s going on inside our mouth, even though we don’t frequently see what’s going on in there. We have a mental image of our mouth and where everything is in relation to other parts. Babies don’t have this “mental map” of their mouth at first.

To help you understand the necessity of a mental map, think about babies learning to stand. Before they can do this, they need to develop “body awareness” or, essentially, a mental “map” of where all their body parts are in relation to each other. Baby lays on the floor and slowly learns to roll around before they ever sit up. Rolling and touching their whole body—from head to toe—while their muscles push and pull helps form the mental “map” of their body. They need deep input all over their body to add all the details to that map. A small touch to one part of their body or a light brush of your hand over their body helps a little but isn’t really enough. It’s the floor’s firm input to the whole body while moving the muscles that really seems to form a clear map.

Rolling and touching their whole body—from head to toe—while their muscles push and pull helps form the mental “map” of their body. They need deep input all over their body to add all the details to that map. A small touch to one part of their body or a light brush of your hand over their body helps a little but isn’t really enough. It’s the floor’s firm input to the whole body while moving the muscles that really seems to form a clear map.

The same goes for the inside the mouth. When things touch the inside of our mouth, a map slowly “draws” in our brain. As babies develops the map inside their mouth, they gain more control, figuring out how to move food around appropriately. They also become more confident in their skill to move food around. This control seems to help quiet the gag response and move it further back in the mouth over time. The baby does not need the gag reflex to eat once they have a clear map and strong coordination. They now have active control to chew the food, know if it’s chewed enough, move it back to swallow, or spit it out and try again.

We know that many types of sensory input in the mouth help babies form the “mental map,” but that bigger inputs are more effective than light sensory inputs. (Think about the difference between a tight hug versus a tickle on the shoulder.)

There are two types of input that feeding therapists know are most effective for sensory-motor learning:

- Touch or tactile input – when food touches a part or many parts of the mouth

- Messages from the muscles and joints or proprioceptive input – when the mouth gnaws on firm or resistive foods that don’t break when chewing.

The simultaneous combination of tactile and proprioceptive input is most effective for forming the map. This is why feeding therapists frequently recommend giving resistive, flavorful foods like a rib bone for baby to chew.

Foods like a rib bone accomplish the trifecta:

- Baby can hold the food, easily put it in their mouth, and pull it back out with their hands, which gives them control to keep the food at the front of their mouth even if they don’t have oral motor control.

- Baby gets big input to their mouth (touch input and muscle feedback as they bite on the bone), which maps the mouth and leads to better control in the future.

- Baby triggers two key reflexes (biting reflex and the tongue lateralization reflex), which mimic chewing and help baby build strength and coordination for future eating.

Are these experiences for eating? No. These are “exercises” to help build a stronger connection between the mouth and the brain. Drawing a detailed map of the mouth contributes to decreasing the sensitivity of the gag. As this map develops, the baby also develops more confidence in their skill, further decreasing the gag’s sensitivity.

Zuri, 9 months, munches on a mango pit. Mango pits are fantastic for working oral-motor skills and low risk as babies cannot bite through them. Quentin, 11 months, works on a spare rib. Spare ribs and even just the bone itself without any meat on it are terrific for helping to map the mouth.Amelia, 10 months, works on a chicken drumstick. For information on how to safely introduce drumsticks, see our Chicken page.Kary Rappaport, a Solid Starts feeding therapist, coaches Reza, 7 months, through a gag on a roasted beet.

Quentin, 11 months, works on a spare rib. Spare ribs and even just the bone itself without any meat on it are terrific for helping to map the mouth.Amelia, 10 months, works on a chicken drumstick. For information on how to safely introduce drumsticks, see our Chicken page.Kary Rappaport, a Solid Starts feeding therapist, coaches Reza, 7 months, through a gag on a roasted beet. Baby gagging on food and throwing up

Baby gagging on food and throwing upGagging with vomit is so hard to watch, though it is pretty normal for some babies just starting solids. Some babies have a stronger or more sensitive gag reflex than others, bringing food up when they gag. This is even more common in babies with a history of reflux. To minimize this reaction, consider these three things:

1. Make sure your baby has at least an hour between a milk feed and table food to let the stomach digest a bit. A super full belly can make a gag turn into vomit much more easily. For example, we often see vomiting with gagging at breakfast, as the belly is super full from a big morning breast/chest feed or bottle.

2. Avoid the foods that tend to trigger the biggest gags for a while. Often, foods that produce lots of gagging are soft, mushy semi-solids like banana and avocado, or fruits and vegetables with skins. These foods can easily stick to the roof of the mouth or tongue and cause strong gagging that leads to throwing up (which often clears the food from the mouth).

3. Offer tons of opportunities for practice with long, resistive, teether type foods (like a mango pit, a spare rib or other thick rib with all lose bits and gristle removed and most of the meat cut off, or a thick pineapple core that does not taper and won’t easily snap or break apart). These foods aren’t for eating, but for helping the brain learn about and desensitize the inside of the mouth. Gagging is the brain’s way of saying “something isn’t right here,” and mouthing these hard, resistive foods that baby can easily pull back out of the mouth helps the brain learn that food isn’t an “intruder.” Mouthing fingers, toys, and infant spoons as teethers outside of mealtimes can also help dampen that gag reflex a bit.

If you try these tips and your baby continues to forcefully gag and vomit at most meals, you may want to mention it to your child’s medical provider.

When to seek helpWe recommend you speak with your child’s pediatrician regarding a referral to a feeding therapist if:

- Baby continues to gag at most meals after an initial learning period (one to two months of finger foods).

- Baby is frequently becoming upset after gagging (crying, tantrums, vomiting).

- Baby is vomiting at most meals, even on an empty stomach.

While it can be disturbing—and nerve-wracking to watch—gagging is a completely normal reflex in infants, children, and adults. Bottom line:

- Babies will likely gag when they first start solids, regardless of starting on purées or finger food.

- Babies who are spoon-fed thin purées are likely to gag less initially but gag more later on when they start finger foods.

- Babies who start with finger foods tend to gag more in the beginning and less later on as their oral-motor skills develop more rapidly.

- All babies gag in their eating journey—it’s one way they learn how to eat. The good news is that babies typically outgrow gagging after a couple of months of practice with various textured finger foods.

Infant CPR & First Aid Resources

One of the most important things you can do to protect baby is take a CPR class online or at your local health facility and review safety procedures. Some resources:

Some resources:

- American Red Cross: Child & Baby CPR

- American Heart Association: Infant CPR Training Kits

- MedlinePlus: Choking First Aid for Infants Under 1

Remember, you are responsible for supervising your child’s health care and for evaluating the appropriateness of the information in this article for your child. Only you know your child and how your child will react to foods and feeding procedures. Although the information presented in this article is based on well-documented research by medical and nutritional professionals, it is up to you to review and consider the information and how it will work with your child.

Always seek the advice of your pediatric doctor, nutritionist or health care provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or feeding issue. You should refer to our Terms of Use for further information.

Reviewed by:

K. Rappaport, OTR/L, MS, SCFES, IBCLC

K. Grenawitzke, OTD, OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC, CNT

- Matsuo K, Palmer JB.

Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: normal and abnormal. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008 Nov;19(4):691-707, vii.

Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: normal and abnormal. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008 Nov;19(4):691-707, vii. - Nishino T. The swallowing reflex and its significance as an airway defensive reflex. Front Physiol. 2012;3:489.

- Rapley, G., & Murkett, T. (2010). Baby-Led Weaning. The Essential Guide to Introducing Solid Foods.

- Naylor, A. J., & Marrow, A. L. (2001). Infant Oral Motor Development in Relation to the Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. Developmental Readiness of Normal Full Term Infants to Progress from Exclusive Breastfeeding to the Introduction of Complementary Foods, 21–25.

- Isaac, N., & Choi, E. (2018). Infant anatomy and physiology for feeding. In S. H. Campbell, J. Lauwers, R., Mannel, & B. Spencer (Eds.), Core curriculum for interdisciplinary lactation care (pp. 37-55). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Naylor, A. J., & Marrow, A. L. (2001). Infant Oral Motor Development in Relation to the Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding.

Developmental Readiness of Normal Full Term Infants to Progress from Exclusive Breastfeeding to the Introduction of Complementary Foods, 21–25.

Developmental Readiness of Normal Full Term Infants to Progress from Exclusive Breastfeeding to the Introduction of Complementary Foods, 21–25. - Naylor, A. J., & Marrow, A. L. (2001). Infant Oral Motor Development in Relation to the Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. Developmental Readiness of Normal Full Term Infants to Progress from Exclusive Breastfeeding to the Introduction of Complementary Foods, 21–25.

- Fangupo, L. J., Heath, A.-L. M., Williams, S. M., Erickson Williams, L. W., Morison, B. J., Fleming, E. A., Taylor, B. J., Wheeler, B. J., & Taylor, R. W. (2016). A Baby-Led Approach to Eating Solids and Risk of Choking. PEDIATRICS, 138(4).

- Fangupo, L. J., Heath, A.-L. M., Williams, S. M., Erickson Williams, L. W., Morison, B. J., Fleming, E. A., Taylor, B. J., Wheeler, B. J., & Taylor, R. W. (2016). A Baby-Led Approach to Eating Solids and Risk of Choking. PEDIATRICS, 138(4).

- Naylor, A.

J., & Marrow, A. L. (2001). Infant Oral Motor Development in Relation to the Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. Developmental Readiness of Normal Full Term Infants to Progress from Exclusive Breastfeeding to the Introduction of Complementary Foods, 21–25.

J., & Marrow, A. L. (2001). Infant Oral Motor Development in Relation to the Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. Developmental Readiness of Normal Full Term Infants to Progress from Exclusive Breastfeeding to the Introduction of Complementary Foods, 21–25. - Fangupo, L. J., Heath, A.-L. M., Williams, S. M., Erickson Williams, L. W., Morison, B. J., Fleming, E. A., Taylor, B. J., Wheeler, B. J., & Taylor, R. W. (2016). A Baby-Led Approach to Eating Solids and Risk of Choking. PEDIATRICS, 138(4).

How to help a child learn to chew?

To chew food, a person needs to use a whole complex of organs: bones, muscles, teeth, tongue, lips, cheeks. The work of each of these components of the chewing apparatus is important and necessary to make grinding food as efficient as possible.

Babies' chewing apparatus is unstable, because they grow, the number and size of their teeth change, so it is impossible to demand from them the unmistakable ability to chew even such simple things as banana slices.

When do babies start chewing?

Between four and six months, babies make their first chewing movements, rhythmically raising their tongue to the palate and lowering it to the lower gum. At the same time, the jaws also move up and down, and intensive rotational movements will appear only by 24-30 months.

Babies actively begin chewing between six and eight months of age. At this point, while doing so, they can only eat pureed and very soft food. But even the consistency of instant porridge helps them develop chewing skills.

By the age of ten months, children have become proficient in language and use it to move food from one cheek to the other.

Most children do not start chewing more or less well before two years of age. However, there is research that tells us that fully mature jaw movements appear in children no earlier than 11 years old, and even then only when they eat gummies.

Why is chewing important?

Teaching the skill of chewing is associated with the development of speech, and with the health of the teeth, and with the formation of bite. And of course, it opens the door for the child to the world of interesting and varied food.

And of course, it opens the door for the child to the world of interesting and varied food.

The sooner you introduce the child to different textures of food (important: without hoping that he will happily accept them), the more likely that as he grows he will be more enthusiastic about dishes of various consistencies with b o and textures. It is best to start acquaintance with food for chewing before ten months - there is evidence that the first meeting with solid food after this age is fraught with a decrease in appetite and vagaries at the table.

How to help the baby develop the chewing apparatus?

Not only the food itself will come to the rescue, but also your emotionality. You can make faces, thus forcing the child to copy you. You can go along with him when he says his funny baby "words" and puts the sounds into syllables. Praise and repeat after him to keep him enthusiastic about active movements of the jaws, tongue and lips.

What should I do if my child chokes or pushes food out of his mouth?

The ejection reflex is the child's natural defense against the threat of suffocation. From five to six months, it gradually fades away. Therefore, you can start offering pieces soon after the start of complementary foods. Do not be afraid - at first the child will really choke and show you all the delights of the gag reflex. Now the most wrong decision would be a sharp return to mashed potatoes and mashed foods, since the process of learning to chew, like many other phenomena in a baby's life, is non-linear, and gives results only as a result of practice.

From five to six months, it gradually fades away. Therefore, you can start offering pieces soon after the start of complementary foods. Do not be afraid - at first the child will really choke and show you all the delights of the gag reflex. Now the most wrong decision would be a sharp return to mashed potatoes and mashed foods, since the process of learning to chew, like many other phenomena in a baby's life, is non-linear, and gives results only as a result of practice.

What kind of food to offer to develop chewing skills?

Offer something that won't break in your mouth or get stuck in your throat. That is, do not give a tiny child dry cookies, blueberries and grapes. Give a banana, avocado, boiled potatoes, baby cottage cheese, a baked apple, later you can switch to boiled or baked beets, melon, peeled cucumber (you can use a nibbler), pieces of cheese, homemade jelly.

What if the child is still choking?

This problem usually occurs in children diagnosed with reflux. They need a little more time to overcome the gag reflex and stop choking. To help them cope with the difficulty, encourage self-interaction with food and minimize the presence of a spoon when feeding semi-solid foods. Do not push and praise your little eater more. And do not resort to violence at the table, this is forever imprinted in the memory of the child as an extremely negative experience that can lead to an eating disorder.

They need a little more time to overcome the gag reflex and stop choking. To help them cope with the difficulty, encourage self-interaction with food and minimize the presence of a spoon when feeding semi-solid foods. Do not push and praise your little eater more. And do not resort to violence at the table, this is forever imprinted in the memory of the child as an extremely negative experience that can lead to an eating disorder.

How to help the baby when regulating

Support Support iconKeywords for searching

Home Home ›!! How to help a child in sprinkling

Home Home 9000

↑ Verkhi 9000 9000

- breastfeeding - breastfeeding a very special time for a mother and her newborn baby. Together with the feeling of closeness and affection that feeding brings, understanding its nuances cannot but raise many questions, including the question of how to help an infant spit up. Regurgitation in a newborn is by no means always the result of a simple pat on his back.

In this article, we'll talk about the basics of helping a newborn spit up, as well as other questions you may have about spitting up.

Why do babies spit up?

Let's get this straight: Why do newborns need to burp in the first place? During feeding, children usually swallow extra air - this is called aerophagia. Spitting up helps prevent this air from entering the intestines, as well as vomiting, gas, and crankiness in the baby. To avoid the return of milk after feeding, you should give the baby the opportunity to burp more often.

How to help a newborn spit up?

During the first six months, the baby should be kept upright in a column for 10-15 minutes after each feed. This will help keep the milk in his stomach, but if the baby occasionally burps anyway, parents need not worry. While carrying your baby in an upright position, you can put a baby diaper or wipes on your shoulder to keep your clothes clean.

We've already seen why spitting up is important, now let's find out how to help your baby spit up. Parents should gently pat the baby on the back with a hand folded in a handful until he burps. Folding your hand into a handful is important because clapping with a flat palm may be too strong for an infant.

Every baby is different and there is no one right position for spitting up. To get started, you can try the following options:

- Sitting position with the baby on the chest. In this position, the parent puts the baby's head with his chin on his shoulder and with one hand supports the baby under the back. With the other hand, you can gently pat the baby on the back. This method is most effective in a rocking chair or when the baby is gently rocking.

- Holding the child upright on your legs. With one hand, parents can hold the baby by the back and head, supporting his chin and placing his palm on the baby’s chest, with the other hand, you can gently pat him on the back.

At the same time, it is important to be careful: do not press the child on the throat, but only gently support his chin.

At the same time, it is important to be careful: do not press the child on the throat, but only gently support his chin. - Holding a baby on your lap while lying on your tummy. Make sure his head is above his chest and gently pat your baby on the back until he burps.

Here are some tips on how best to help your newborn spit up:

- Let your baby spit up while feeding. If the baby is restless or has swallowed air, it is worth giving him the opportunity to burp during feeding, and not just after.

- When bottle feeding, let the newborn burp after every 50-60 ml.

- When breastfeeding, let the baby burp at every breast change.

It is important to let your baby spit up after eating, even if he spit up during feeding!

If your baby is gassy, spit up more often. Also, if he vomits frequently or suffers from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), have him spit up after every 30 ml bottle-feeding or every five minutes while breastfeeding.

How long should a baby be held for it to burp? It's different for everyone, but generally keeping a newborn upright for 15 to 20 minutes after a feed helps the milk stay in the baby's stomach.

Minimize the amount of air you swallow. Gas production and regurgitation result from aerophagia during feeding. The baby will inevitably swallow air, but there are ways to prevent it from swallowing too much. Whether you bottle feed your baby or combine breastfeeding with bottle feeding, the Philips Avent anti-colic bottle with AirFree valve is designed so that the nipple is always filled with milk without excess air, even in a horizontal position, thus preventing the baby from swallowing excess air during feeding.

Reducing the amount of air your baby swallows can help reduce your baby's risk of colic, gas, and spitting up.

Breastfeeding is a wonderful time to strengthen the bond between parent and baby. Every mom and every baby is different, so learning to help your newborn burp properly can take time and practice.