When should babies start eating solid foods

When, What, and How to Introduce Solid Foods | Nutrition

For more information about how to know if your baby is ready to starting eating foods, what first foods to offer, and what to expect, watch these videos from 1,000 Days.

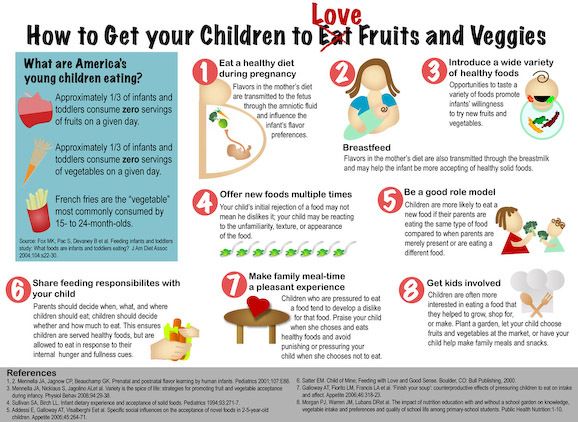

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend children be introduced to foods other than breast milk or infant formula when they are about 6 months old. Introducing foods before 4 months old is not recommended. Every child is different. How do you know if your child is ready for foods other than breast milk or infant formula? You can look for these signs that your child is developmentally ready.

Your child:

- Sits up alone or with support.

- Is able to control head and neck.

- Opens the mouth when food is offered.

- Swallows food rather than pushes it back out onto the chin.

- Brings objects to the mouth.

- Tries to grasp small objects, such as toys or food.

- Transfers food from the front to the back of the tongue to swallow.

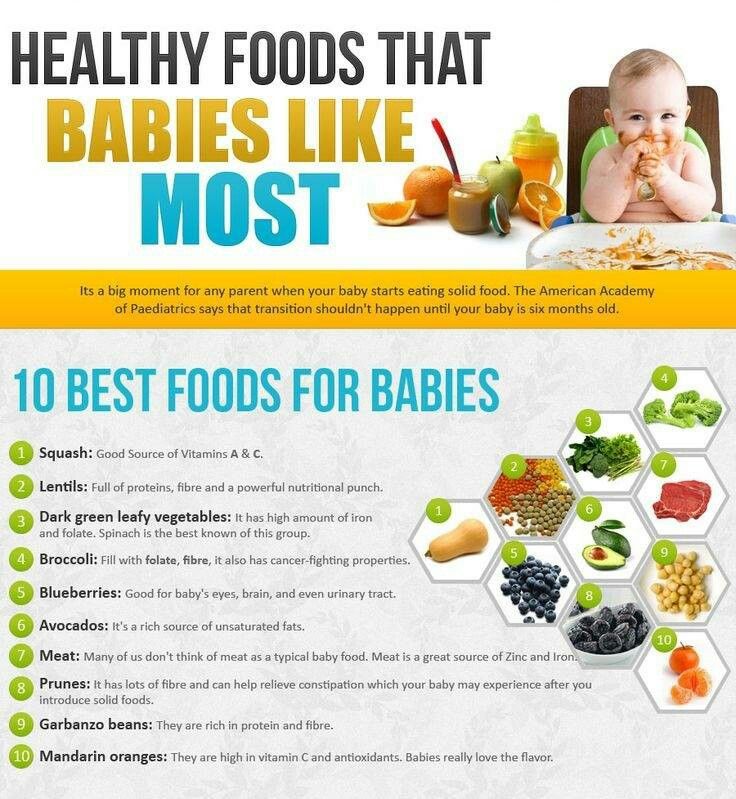

What Foods Should I Introduce to My Child First?

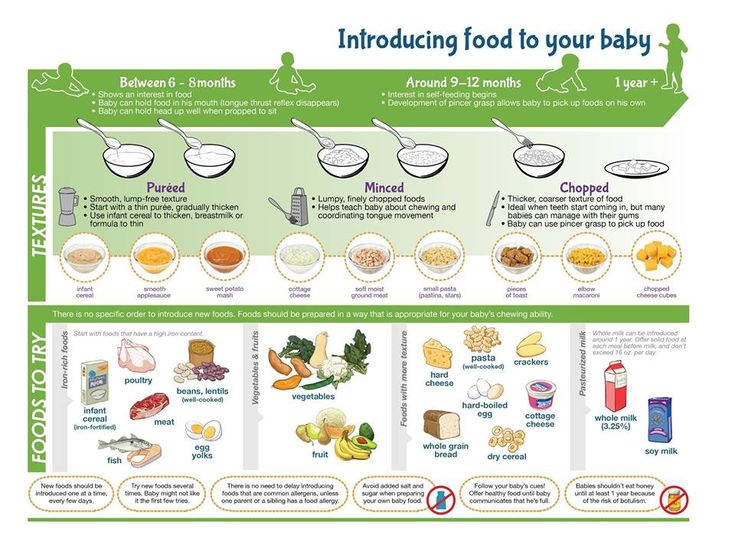

The American Academy of Pediatrics says that for most children, you do not need to give foods in a certain order. Your child can begin eating solid foods at about 6 months old. By the time he or she is 7 or 8 months old, your child can eat a variety of foods from different food groups. These foods include infant cereals, meat or other proteins, fruits, vegetables, grains, yogurts and cheeses, and more.

If your child is eating infant cereals, it is important to offer a variety of fortifiedalert icon infant cereals such as oat, barley, and multi-grain instead of only rice cereal. Only providing infant rice cereal is not recommended by the Food and Drug Administration because there is a risk for children to be exposed to arsenic. Visit the U.S. Food & Drug Administrationexternal icon to learn more.

How Should I Introduce My Child to Foods?

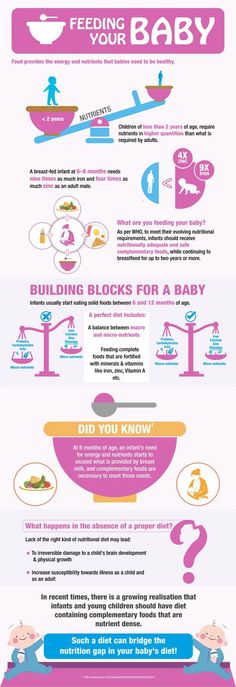

Your child needs certain vitamins and minerals to grow healthy and strong.

Now that your child is starting to eat food, be sure to choose foods that give your child all the vitamins and minerals they need.

Click here to learn more about some of these vitamins & minerals.

Let your child try one single-ingredient food at a time at first. This helps you see if your child has any problems with that food, such as food allergies. Wait 3 to 5 days between each new food. Before you know it, your child will be on his or her way to eating and enjoying lots of new foods.

Introduce potentially allergenic foods when other foods are introduced.

Potentially allergenic foods include cow’s milk products, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soy, and sesame. Drinking cow’s milk or fortified soy beverages is not recommended until your child is older than 12 months, but other cow’s milk products, such as yogurt, can be introduced before 12 months. If your child has severe eczema and/or egg allergy, talk with your child’s doctor or nurse about when and how to safely introduce foods with peanuts.

How Should I Prepare Food for My Child to Eat?

At first, it’s easier for your child to eat foods that are mashed, pureed, or strained and very smooth in texture. It can take time for your child to adjust to new food textures. Your child might cough, gag, or spit up. As your baby’s oral skills develop, thicker and lumpier foods can be introduced.

Some foods are potential choking hazards, so it is important to feed your child foods that are the right texture for his or her development. To help prevent choking, prepare foods that can be easily dissolved with saliva and do not require chewing. Feed small portions and encourage your baby to eat slowly. Always watch your child while he or she is eating.

Here are some tips for preparing foods:

- Mix cereals and mashed cooked grains with breast milk, formula, or water to make it smooth and easy for your baby to swallow.

- Mash or puree vegetables, fruits and other foods until they are smooth.

- Hard fruits and vegetables, like apples and carrots, usually need to be cooked so they can be easily mashed or pureed.

- Cook food until it is soft enough to easily mash with a fork.

- Remove all fat, skin, and bones from poultry, meat, and fish, before cooking.

- Remove seeds and hard pits from fruit, and then cut the fruit into small pieces.

- Cut soft food into small pieces or thin slices.

- Cut cylindrical foods like hot dogs, sausage and string cheese into short thin strips instead of round pieces that could get stuck in the airway.

- Cut small spherical foods like grapes, cherries, berries and tomatoes into small pieces.

- Cook and finely grind or mash whole-grain kernels of wheat, barley, rice, and other grains.

Learn more about potential choking hazards and how to prevent your child from choking.

Top of Page

First Bites—Why, When, and What Solid Foods to Feed Infants

1. Sellen DW. Evolution of infant and young child feeding: implications for contemporary public health. Ann Rev Nutr. (2007) 27:123–48. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092557 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ann Rev Nutr. (2007) 27:123–48. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092557 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Herculano-Houzel S. The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its associated cost. PNAS. (2012) 109:10661–8. 10.1073/pnas.1201895109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Fonseca-Azevedo K, Herculano-Houzel S. Metabolic constraint imposes tradeoff between body size and number of brain neurons in human evolution. PNAS. (2012) 109:18571–6. 10.1073/pnas.1206390109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Organ C Nunn CL, Machanda Z, Wrangham RW. Phylogenetic rate shifts in feeding time during evolution nof Homo. PNAS. (2011) 108:14555–9. 10.1073/pnas.1107806108 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Wrangham RW, Jones JH, Laden G, Pilbeam D, Conklin-Brittain N. The raw and the stolen. Cooking and the ecology of human origins. Curr Anthropol. (1999) 40:567–94. 10.1086/300083 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1086/300083 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Herculano-Houzel S, Kaas JH. Gorilla and orangutan brain conform to the primate cellular scaling rules: implications for human evoluation. Brain Behav Evol. (2011) 77:33–44. 10.1159/000322729 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Humphrey LT. Weaning behavior in human evolution. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2010) 21:453–61. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.11.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Knott C. Reproductive ecology and human evolution. In: Ellison, editor. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; (2001). p. 429–63. [Google Scholar]

9. Sellen DW. Comparison of infant feeding patterns reported for nonindustrial populations with current recommendations. J Nutr. (2001) 131:2707–15. 10.1093/jn/131.10.2707 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. WHO . Exclusive Breast Feeding for Six Months Best for Babies Everywhere. (2011). Available online at: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/ (accessed March 24, 2020).

11. AAP Section on Breastfeeding . Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. (2012). 129:e827–e841. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. AAFP . Breastfeeding Policy Statement. (2017). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding.html (accessed March 24, 2020).

13. ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women . ACOG committee opinion no. 361: breastfeeding: maternal and infant aspects. Obstet Gynecol. (2007) 109:479–80. 10.1097/00006250-200702000-00064 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellof M, Embleton N, Fidler Mis N, et al.. Complementary feeding: a position paper by the european society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition (ESPGHAN) committee on nutrition. J Pediatr Gastro Nutr. (2017) 64:119–32. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001454 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Clayton HR, Perrine LR, Scanlon KS. Prevalence and reasons for introducing infants early to solid foods: variations by milk feeding type. Pediatrics. (2013) 131:e1108–14. 10.1542/peds.2012-2265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. (2013) 131:e1108–14. 10.1542/peds.2012-2265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Scott JA. Predictors of the early introduction of solid foods in infants: results of a cohort study. BMC Pediatr. (2009) 9:60. 10.1186/1471-2431-9-60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Costantini C, Harris H, Reddy V, Akehurst L, Fasulo A. Introducing complementary foods to infants: does age really matter? A look at feeding practices in two European Communities: British and Italian. Child Care Pract. (2019) 25:326–41. 10.1080/13575279.2017.1414033 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Orenstein SR, Magill HL, Brooks P. Thickening of infant feedings for therapy of gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. (1987) 110:181–6. 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80150-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Perkins MR, Bahnson HT, Logan K, Marrs T, Radulovic S, Craven J, et al.. Association of early introduction of solids with infant sleep: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. (2018) 172:e180739. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0739 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

JAMA Pediatr. (2018) 172:e180739. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0739 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Rosenstein D, Oster H. Differential facial responses to 4 basic tastes in newborns. Child Dev. (1988) 59:1555–68. 10.2307/1130670 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Cook CK. Taste perception in the newborn infant. Infant Behav Dev. (1978) 1:52–69. 10.1016/S0163-6383(78)80009-5 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. (1982) 3:139. 10.1016/S0195-6663(82)80007-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Schaal B, Marlier L, Soussignan R. Human fetuses learn odours from their pregnant mother's diet. Chem Senses. (2000) 25:729–37. 10.1093/chemse/25.6.729 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Hauser GJ, Chitayat D, Berns L, Braver D, Muhlbauer B. Peculiar odors in newborns and prenatal ingestion of spicy food. Eur J Pediatr. (1985) 144:403. 10. 1007/BF00441788 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1007/BF00441788 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Menella JA, Johnson A, Beauchamp GK. Garlic ingestion by pregnant women alters the odor of amniotic fluid. Chem Senses. (1995) 20:207–9. 10.1093/chemse/20.2.207 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Ross M, Nijland MJ. Fetal swallowing: relation to amniotic fluid regulation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. (1997) 40:352–65. 10.1097/00003081-199706000-00011 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Hepper PG. Human fetal olfactory learning. Int J Prenat Perinat Psychol Med. (1995) 7:145–51. [Google Scholar]

28. Menella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. (2001) 107:e88. 10.1542/peds.107.6.e88 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Hepper PG, Wells DL, Dorman JC, Lynch C. Long-term flavor recognition in humans with prenatal garlic experience. Dev Psychobiol. (2013) 55:568. 10.1002/dev.21059 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Menella JA, Beauchamp GK. Maternal diet alters the sensory qualities of human milk and the nursling's behavior. Pediatrics. (1991) 88:737–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Menella JA, Beauchamp GK. Maternal diet alters the sensory qualities of human milk and the nursling's behavior. Pediatrics. (1991) 88:737–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Maier AS, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Leathwood PD, Issanchou SN. Breastfeeding and experience with variety early in weaning increases infants' acceptance of new foods for up to two months. Clin Nutr. (2008) 27:849–57. 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.08.002 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Harris G, Mason S. Are there sensitive periods for food acceptancy in infancy? Curr Nutr Rep. (2017) 6:190–96. 10.1007/s13668-017-0203-0 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Mennella J, Beauchamp GK. Developmental changes in the acceptance of protein hydrolysate formula. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (1996) 17:386–91. 10.1097/00004703-199612000-00003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Beauchamp GK, Mennella J. Early flavor learning and its impact on later feeding behavior. J Ped Gastro Nutr. (2009) 43:S25–30. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819774a5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819774a5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Maier A, Chabanet C, Schaal B, Issanchou S, Leathwood P. Effects of repeated exposure on acceptance of initially disliked vegetables in 7-month old infants. Food Qual and Pref. (2007) 18:1023–32. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.04.005 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Remy E, Issanchou S, Chabanet C, Nicklaus S. Repeated exposure of infants at complementary feeding to a vegetable puree increases acceptance as effectively as flavor-flavor learning and more effectively than flavor-nutrient learning. J Nutr. (2013) 143:1194–200. 10.3945/jn.113.175646 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Caton SJ, Ahern SM, Remy E, Nicklaus S. Repetition counts: repeated exposure increases intake of a novel vegetable in UK pre-school children compared to flavor-flavour and flavor-nutrient learning. Br J Nutr. (2013) 109:2089–97. 10.1017/S0007114512004126 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Maier-Noth A, Schaal B, Leathwood P, Issanchou S. The lasting influences of early food-related variety experience: a longitudinal study of vegetable acceptance from 5 months to 6 years in two populations. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0151356. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

The lasting influences of early food-related variety experience: a longitudinal study of vegetable acceptance from 5 months to 6 years in two populations. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0151356. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Geisel EG. Effect of food texture on the development of chewing of children between six months and two years of age. Dev Med Child Neurol. (1991) 3:69–79. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1991.tb14786.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Blossfeld I, Collins A, Kiely M, Delahunty C. Texture preferences of 12-month-old infants and role of early experiences. Food Qual Pref. (2007) 18:396–404. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2006.03.022 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Northstone K, Emmett P, Nethersole F. The effect of age of introduction to lumpy solids on foods eaten and reported feeding difficulties at 6 and 15 months. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2001) 14:43–54. 10.1046/j.1365-277X.2001.00264.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Harris G, Coulthard H. Early eating behaviours and food acceptance revisited: breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods as predictive of food acceptance. Curr Obes Rep. (2016) 5:113–20. 10.1007/s13679-016-0202-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Harris G, Coulthard H. Early eating behaviours and food acceptance revisited: breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods as predictive of food acceptance. Curr Obes Rep. (2016) 5:113–20. 10.1007/s13679-016-0202-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Fiocchi A, Assa'ad A, Bahna S. Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Ann Allergy Asthma Allergy Immunol. (2006) 97:10–21. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61364-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Abrams EM, Greehawt M, Fleischer DM, Chan ES. Early solid food introduction: role in food allergy prevention and implications for breastfeeding. J Pediatr. (2017) 184:13–8. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.053 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al.. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. NEJM. (2015) 372:803–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414850 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Du Toit G, Sayre PH, Graham-Roberts DM, Sever ML, Lawson K, Bahnson HT, et al.. Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. NEJM. (2016) 374:1435–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Du Toit G, Sayre PH, Graham-Roberts DM, Sever ML, Lawson K, Bahnson HT, et al.. Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. NEJM. (2016) 374:1435–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514209 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Perkins MR, Logan K, Tsent A, Raji B, Ayis S, Peacock J, et al.. Randomized trial of introduction of allergenic foods in breast-fed infants. NEJM. (2016) 374:1733–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Prescott SL, Smith P, Tang M, et al.. he importance of early complementary feeding in the development of oral tolerance: concerns and controversies. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2008). 19:375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Daniels L, Mallan KM, Fildes A, Wilson J. The timing of solid introduction in an “obesogenic” environment: a narrative review of the evidence and methodologic issues. Austr and NZ J Pub Health. (2015) 39:366–73. 10.1111/1753-6405.12376 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Mehta KC, Specker BL, Bartholomy S, Giddens J, Ho ML. Trial on timing of introduction of solids and food type on infant growth. Pediatr. (1998) 102:569–73. 10.1542/peds.102.3.569 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Trial on timing of introduction of solids and food type on infant growth. Pediatr. (1998) 102:569–73. 10.1542/peds.102.3.569 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Jonsdottir OH, Kleinman RE, Wells JC, Fewtrell MS, Hibbard PL, Gunnlaugsson G, et al.. Exclusive breastfeeding for 4 versus 6 months and growth in early childhood. Acta Paediatr. (2014) 103:105–11. 10.1111/apa.12433 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Leunissen RW, Kerkhof GF, Stijnen T. Timing and tempo of first-year rapid growth in relation to cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in early adulthood. JAMA. (2009) 301:2234–42. 10.1001/jama.2009.761 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Laursen MF, Bahl MI, Michaelsen KF, Licht TR. First foods and gut microbes. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:356. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

how and when to introduce solid food to a child

Solid food: how and when to introduce solid food to a child Expecting new skills from the baby, do not rush things. It is necessary to acquaint the child with solid food no earlier than 6-7 months. At this time, the desire to scratch the gums, ready for the appearance of the first teeth, will coincide with the interest in adult food.

It is necessary to acquaint the child with solid food no earlier than 6-7 months. At this time, the desire to scratch the gums, ready for the appearance of the first teeth, will coincide with the interest in adult food.

Dry initial milk formula adapted by Valio Baby 1 NutriValio for feeding children from birth to 6 months Read more

Follow-up dry milk formula adapted by Valio Baby 2 NutriValio for feeding children from 6 to 12 months More

Dry milk drink "Baby milk" Valio Baby 3 NutriValio for feeding children over 12 months Read more

Children are born with a vital, unconditioned reflex - sucking. They are ready to suck on their mother's breasts, but all solid objects that have fallen into their mouths are automatically pushed out so as not to choke (a protective reflex is triggered). Therefore, parents are not recommended to accustom the baby to solid foods too early. This will cause not only rejection, but sometimes vomiting. The ideal time is considered to be the start of complementary foods. When the first teeth begin to grow in the child, you can replace the homogenized puree with food with the addition of soft fibers. They will be to the taste of the baby, as they will massage itchy gums. An important clue for parents is also the child's interest in adult food. If the baby looks into your plate, tries not to suck on mashed potatoes in a spoon, but to remove it with his upper lip and chew - it's time to introduce more solid food into the children's menu. First, at the tip of the spoon, offer the baby vegetable and cereal side dishes, closer to 9months you can give pieces of well-boiled meat. The kid does not immediately learn to chew them, and the food will come out with a stool almost in its original form. It's not scary, over time the child will learn everything.

Therefore, parents are not recommended to accustom the baby to solid foods too early. This will cause not only rejection, but sometimes vomiting. The ideal time is considered to be the start of complementary foods. When the first teeth begin to grow in the child, you can replace the homogenized puree with food with the addition of soft fibers. They will be to the taste of the baby, as they will massage itchy gums. An important clue for parents is also the child's interest in adult food. If the baby looks into your plate, tries not to suck on mashed potatoes in a spoon, but to remove it with his upper lip and chew - it's time to introduce more solid food into the children's menu. First, at the tip of the spoon, offer the baby vegetable and cereal side dishes, closer to 9months you can give pieces of well-boiled meat. The kid does not immediately learn to chew them, and the food will come out with a stool almost in its original form. It's not scary, over time the child will learn everything. It is important not to ignore his desire, you will have to pay for the pedagogical miscalculation and literally teach the child to chew.

It is important not to ignore his desire, you will have to pay for the pedagogical miscalculation and literally teach the child to chew.

Of course, not everything can go according to plan. The most common reasons why a child refuses solid food:

-

The pieces of food are too big.

-

You are using the wrong feeding technique.

-

The spoon is big for a child.

-

The child has unpleasant associations - perhaps you gave him medicine from this spoon. Do not use everyday baby utensils for unpleasant procedures.

-

The child is in a bad mood or does not feel well.

In no case do not force the baby to eat if he refuses. Gently try again and again. Set an example - eat the first spoon yourself, showing the crumbs how tasty his food is. If the child still cannot cope with solid food, it is worth contacting a pediatric osteopath. The baby may have a non-standard structure of the maxillofacial system, subluxation of the jaw associated with birth trauma, problems with muscle tone. The timely introduction of solid food is very important not only for the full nutrition of the child, it affects his future speech activity. Breastfeeding is a good prevention of speech therapy problems. In order to suck milk from the breast, the child needs to make more efforts than when feeding from a bottle - this is a good (and what is valuable - natural) training of the jaws and muscles of the tongue, and it must be continued by introducing the crumbs to solid food in time. Of course, a baby with a piece of an apple in his hands (and in his mouth) must be looked after so that he does not choke. By the way, for the development of the chewing and speech apparatus, it is useful to grimace with the baby during the game - this strengthens the facial muscles well.

The baby may have a non-standard structure of the maxillofacial system, subluxation of the jaw associated with birth trauma, problems with muscle tone. The timely introduction of solid food is very important not only for the full nutrition of the child, it affects his future speech activity. Breastfeeding is a good prevention of speech therapy problems. In order to suck milk from the breast, the child needs to make more efforts than when feeding from a bottle - this is a good (and what is valuable - natural) training of the jaws and muscles of the tongue, and it must be continued by introducing the crumbs to solid food in time. Of course, a baby with a piece of an apple in his hands (and in his mouth) must be looked after so that he does not choke. By the way, for the development of the chewing and speech apparatus, it is useful to grimace with the baby during the game - this strengthens the facial muscles well.

2.71 7

Power supplyShare:

Ivargizova Oksana

Medical Institute. Pavlova, specialization - pediatrics

Author: Reetta Tikanmäki

Palm oil in baby food

Infant milk formulas are made from cow's milk. However, in terms of fat composition, it differs significantly from that of the mother.

Read

Author: Ivargizova Oksana

How to choose milk formula for a baby

Breast milk is the best food for a newborn baby. It contains all the necessary nutritional components that fully meet the needs of the child and are necessary for his healthy and harmonious development.

Read

Show all

We want to make our site more convenient for you, so we collect analytical data about your visit using cookies. By continuing to use the site, you agree to this. For more information on the collection and processing of data, please see the Personal Data Processing Policy.

By continuing to use the site, you agree to this. For more information on the collection and processing of data, please see the Personal Data Processing Policy.

Password recovery

To recover your password, enter your e-mail, which you specified during registration. We will send you a message with further instructions to this e-mail

Thank you for contacting us!

A letter with information to reset your password

has been sent to your mail

Back to the site

YOUR CITY -

?

Yes Change

We want to make our site more convenient for you, so we collect analytical data about your visit using cookies. By continuing to use the site, you agree to this. For more information on the collection and processing of data, please see the Personal Data Processing Policy.

SELECT CITY

How to teach a child to chew solid food?

Shalunova Anastasia Ivanovna

Member of the Russian Union of Nutritionists, Nutritionists and Food Industry Specialists

Bring the spoon to your mouth, play with your food, twist the food with your tongue, spit it out, take a bite, try to chew it, and finally swallow a piece... What children do to cope with adult food, which at first seems so "difficult"! We tell you how to teach your child to chew solid food so that it does not become a family problem. Consulted by nutritionist Anastasia Ivanovna Shalunova.

- Anastasia Ivanovna, let's talk about how to teach a child to chew and swallow solid food. Why is age important here?

— It is important not to miss the right moment when chewing is the easiest to develop. The most optimal period is from 6 to 10 months, with the introduction of complementary foods with pieces. However, the boundaries of the norm are conditional, because a child can only eat liquid food at a year and a half.

However, the boundaries of the norm are conditional, because a child can only eat liquid food at a year and a half.

Children begin to chew due to the development of the physiological and neuropsychological processes of the body - this is individual for each child. And here the influence of caesarean section and natural childbirth is also very important, how the birth process proceeded and how the baby developed from birth.

When to give your baby solid food

— How do parents know when their baby is ready to chew solid food?

— Food interest is conditionally formed from 4 to 6 months, when a child pulls a plate, a spoon towards himself, asks for food. During this period, complementary foods begin, gradually moving from homogeneous puree-like dishes to more dense, with pieces.

The child is ready to chew food if:

- he confidently picks up and holds a spoon;

- sits without adult support;

- receives complementary foods for three to four weeks.

From 6 to 10 months, it is easier to teach a baby to eat and chew food in bite-size pieces. If the child does not gnaw, but sucks or licks what was given to him, there is no need to forbid him - perhaps he is not hungry or he is interested in something else at the moment.

In the absence of interest in food for up to a year, work with psychologists, neuropsychologists, and neurologists may be necessary. Each of them will look at the children's problem from their side and give recommendations.

— How many teeth are enough to start chewing?

— You can “chew” food even without teeth, rubbing the pieces with your gums. Some children have teeth late, but they are still given solid food in order to develop chewing skills. At the same time, chewing can stimulate blood circulation and tooth growth.

Read also

- What "adult" food can be given to a baby under one year old and when to start the transition to a common table.

— What problems can arise if a child does not chew food?

- Some parents complain that the child chokes on solid food or that he does not chew, but swallows immediately. This may be due to the late introduction of solid foods.

In addition, if a child does not chew food well, this provokes problems with digestion. You should not load the immature digestive system of the baby, as the child's body does not yet produce enough enzymes. In this case, the child will refuse food, will eat or chew less often.

What principles of nutrition should be followed:

- give the child a variety of foods, but in reasonable quantities, and watch the body's reaction;

- slow eating improves digestion and increases the feeling of fullness, so it is important to remember to chew your food thoroughly;

- with a healthy diet, it is better to avoid feeding in front of the TV and phone, or use them very pointwise. Gadgets distract from food, lead to unconscious and rapid consumption of food, and this can result in metabolic syndrome and subsequently lead to overweight or type II diabetes.

— How do you feel about tongue massage to improve food processing?

- Tongue massage is very often used by speech therapists to relieve muscle spasms in dysarthria in children when pronunciation suffers. During massage, fingers, toothbrushes, probes are used, which can be traumatic for a child.

Parents of such children should be aware of the contraindications to speech therapy massage:

- skin rashes, swelling, wounds;

- herpetic infections of the mouth;

- colds;

- severe forms of chronic diseases;

- oncological, neuropsychiatric diagnoses.

- How to teach a child to chew food - where to start? What size should the pieces be?

— In order to make chewing effective and fun, a child must have an interest in food. Favorite product will be chewed best. It is also necessary to take into account the novelty of sensations and introduce new foods when the baby is hungry.

Nuances that parents should pay attention to:

- Be sure to develop food interest and build a diet, that is, the child should be hungry for the next meal.

- It is best to start with chunks in foods that the child has already eaten pureed. The taste will be familiar to him, but the texture will be slightly different.

- Cooking of vegetables is encouraged.

- It is important to look at whether the baby is coping with his portion. The first pieces are given no larger than a match head, then the size of a little finger nail, then everything is larger. You can give the baby in the hand slices of fresh fruits, baby cookies, crackers.

- Nibbler recommended for a smooth transition from puree to chunks. With him, the child eats on his own, and helps teeth erupt.

- The behavior of parents influences the child's behavior at the table. If meeting at dinner or lunch is a family tradition, then the child automatically joins it and gets used to it, focusing on the example of the parents.

Do not give up trying to give solid food, even if the child spits out the food. But you don’t need to push the product either: you can offer it at a different moment, vary the pieces in size. Also, do not be afraid to give solid food to the child and be nervous during his training and feeding. Anxiety and panic are transmitted on a subconscious level - the baby can just hurry up and choke.

— What mistakes do parents make when feeding their baby?

— Most often, parents are in a hurry. They should pay attention to the formation of the oral apparatus and the psychological readiness of the baby to eat independently, chew and swallow the food bolus. It often happens that during the period of adaptation of the child, for example, after vaccination or moving, the mother begins to give him something unfamiliar and teach him new skills. This will only complicate the task.

If a child flatly refuses to chew solid food, do not force feed him, you need to find out the reason.

- And finally, probably one of the most popular parenting questions - cartoons while eating. What are the pros and cons?

- The child will be distracted from food by cartoons, which will negatively affect the whole process of eating. The purpose of eating is for the child to eat and realize that he is full. "If you're hungry, let's eat, if you want cartoons, watch them later" - these should be the rules. These actions must be distinguished, because watching cartoons is accompanied by other mental and motor processes.

Main recommendations:

- Take your time, stimulate chewing processes and do not forget about physiology: how ready the child's body, oral apparatus, communication systems are.

- Be more attentive to the baby, do not switch to your problems. The task of parents is to ensure that the child is fed, fed and develops correctly. To do this, it is important to build nutrition, taking into account the needs of the child and the processes occurring in the body.

Methods for teaching a child to chew are different, but two aspects are important in this matter: physiological and psychological. Solid foods are introduced from around six months of age, and children should be taught to chew solids before the age of one. In this case, the process depends on the received complementary foods, and on the home environment. It is important for parents to be patient during the learning process and gradually move from pureed food to regular feeding of the baby with solid food with pieces. Only then will he learn to chew and begin to enjoy the new food and his new abilities.

* Breast milk is the best food for babies. WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of a child's life and continued breastfeeding after complementary foods are introduced until the age of 2 years. Before introducing new products into the baby's diet, you should consult with a specialist. The material is for informational purposes and cannot replace the advice of a healthcare professional.