Woman breast feeds friends baby

My friend breastfed my baby | Breastfeeding

We were on a summer double date under the string lights in the garden at Frankie’s in Brooklyn when Miranda told us she was pregnant. I was pregnant, too, we crowed, and just about as far along. Our husbands beamed. I’d only recently met Miranda, but I didn’t know anyone else expecting a baby: I was delighted to count her as a new friend. Throughout that autumn, we walked to prenatal yoga, discussed midwives and backaches and cravings and marriage and hopes and family, and made our respective preparations.

Miranda’s son was born in a birth centre on New Year’s Day, after three days of labour. We visited when they returned home, sat under their still-twinkling Christmas tree, ooh-ing and ahh-ing over the new person. Her mother, a former midwife, and sister were by her side. The place was warm and calm, full of love. Miranda held court from a sofa bed. I cradled her newborn son against my own, still in utero, and marvelled at the turn my life had taken.

I entertained a parade of well-meaning relatives and friends in increasingly wild pain. Inside I was unravelling

Two weeks later, I gave birth at home, after a 13-hour posterior, or back-to-back, labour, which the long-practising, well-respected midwife did not bother to attend. Frankly, it felt like staring death in the face, by which I mean an altogether normal and intense physiological process that has nothing to do with the ordinariness of daily life. Throughout, my husband and doula repeatedly called and texted the midwife, whom we had found privately. She told us it was “probably” early labour. From inside the grip of what turned out to be very active labour, I managed to flat-out demand that she join us, speaking at the phone while the doulka held it to my ear. The midwife sounded annoyed, vaguely put-upon. It was another three hours before she arrived. Minutes later, with a great and unbridled roar, I delivered my son into bathwater.

We wept with joy, held him, kissed him, named him. Eventually, I got out of the bath. My husband lay in bed with our new son on his chest. I showered in a state of trembling, happy shock. The midwife perched on the sink and told me a story about her estranged sister. She handed me a towel, and I remember commiserating, trying to comfort her about her unfortunate relationship with her family, as though we were two cool girls hanging out in the bathroom at a party. One of us just happened to be naked and bleeding, immediately postpartum. I didn’t care; I was too ecstatic. Having just given birth, I felt omnipotent. Epic. Heroic. Unstoppable.

Eventually, I got out of the bath. My husband lay in bed with our new son on his chest. I showered in a state of trembling, happy shock. The midwife perched on the sink and told me a story about her estranged sister. She handed me a towel, and I remember commiserating, trying to comfort her about her unfortunate relationship with her family, as though we were two cool girls hanging out in the bathroom at a party. One of us just happened to be naked and bleeding, immediately postpartum. I didn’t care; I was too ecstatic. Having just given birth, I felt omnipotent. Epic. Heroic. Unstoppable.

In the days that followed, I entertained a parade of well-meaning but exhausting relatives and friends. I also breastfed around the clock, in increasingly wild pain: engorged and throbbing. I served tea and showed off my newborn and made small talk and acted politely with my guests. Inside, I was unravelling. My home bore little resemblance to the intimate, intensely nurturing bubble I’d witnessed at Miranda’s. The last thing I needed was to be entertaining guests who seemed embarrassed and uncomfortable when I nursed. A deep, overwhelming exhaustion began to take root.

The last thing I needed was to be entertaining guests who seemed embarrassed and uncomfortable when I nursed. A deep, overwhelming exhaustion began to take root.

At a week-and-a-half old, my baby began to lose weight. Breastfeeding was not going well. This was not abnormal, we were reassured. The baby had a bad latch (meaning his mouth and jaw weren’t yet perfectly coordinated on my breast), or I had low supply, or he had a bad latch because of my low supply, or I had low supply because of the bad latch. One lactation consultant offered advice that was contradicted by a second, whose advice was contradicted by a third. I should use a breast pump every two hours. I should supplement with formula. I should neither pump nor supplement; I should let him get so hungry he would do whatever it took to latch properly. Around and around we went.

Around and around we went.

Meanwhile, the baby kept losing weight. One of the lactation consultants wrote down information for breast milk banks in New York, but I didn’t think we were that desperate. I appealed to the midwife via email. She suggested I “take it easy”, and was never heard from again. The paediatrician told me to give up and formula feed. That suggestion sent me into a tailspin: I had been fed with formula as a baby myself, and I wanted every kind of distance from my own upbringing. This was going to be different. This was a fresh start. This was ours, and it was new, and it was pure. The imperative to feed my baby from myself blotted out the sun. It was implied by several people in my orbit that this kind of purist thinking was crazy, which only cemented my determination. A line from the poet Muriel Rukeyser ricocheted through my mind: “Pay attention to what they tell you to forget.”

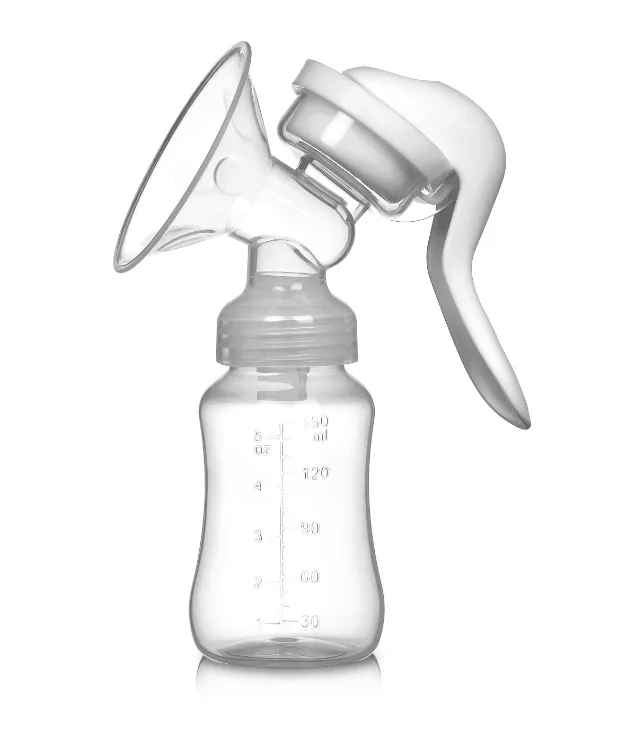

I tried to be cheerful, but when we were alone, I wept, lashed out at my husband, and spiralled into exhausted, muddy irrationality, panicked about failing the precious boy we had only just met. There was very little distinction between day and night. Time took on a strange new cast. I nursed and pumped and nursed and pumped and nursed some more. I remember my husband singing to our crying son while I soaked my breasts in bowls of warm, salty water. I remember cooling my breasts with cabbage leaves, drinking herbal tinctures, pumping and pumping and pumping. I remember hoping each new lactation consultant was going to be The One. I remember hoping the midwife would drop by, or at least return a call. The baby was wetting nappies, but he needed to nurse constantly, and never got a full belly on which he (and I) could rest for a few hours. What was going wrong? Surely I could do this. There must be a way, if only I worked long and hard enough. If only I soldiered on through one more sleepless night, and then one more.

There was very little distinction between day and night. Time took on a strange new cast. I nursed and pumped and nursed and pumped and nursed some more. I remember my husband singing to our crying son while I soaked my breasts in bowls of warm, salty water. I remember cooling my breasts with cabbage leaves, drinking herbal tinctures, pumping and pumping and pumping. I remember hoping each new lactation consultant was going to be The One. I remember hoping the midwife would drop by, or at least return a call. The baby was wetting nappies, but he needed to nurse constantly, and never got a full belly on which he (and I) could rest for a few hours. What was going wrong? Surely I could do this. There must be a way, if only I worked long and hard enough. If only I soldiered on through one more sleepless night, and then one more.

Miranda came over with her by now pleasingly plump one-month-old. He was breastfeeding like gangbusters. Miranda’s mother – a veritable caricature of maternal sweetness – had moved in for a while to cook and clean and nuzzle and hum. Miranda seemed to be more or less OK. This amazed me. I had not yet left the apartment, was shuffling around in strange combinations of maternity clothes and pyjamas. She unzipped her son from his winter layers to reveal a wacky costume: she had dressed him in all the colours of the rainbow to cheer me up. As we talked, she mentioned in passing that the most effective way to gauge the quality of a newborn’s latch is to have him latch on to someone who knows what a good latch feels like. Interesting, I thought, and filed it away.

He was breastfeeding like gangbusters. Miranda’s mother – a veritable caricature of maternal sweetness – had moved in for a while to cook and clean and nuzzle and hum. Miranda seemed to be more or less OK. This amazed me. I had not yet left the apartment, was shuffling around in strange combinations of maternity clothes and pyjamas. She unzipped her son from his winter layers to reveal a wacky costume: she had dressed him in all the colours of the rainbow to cheer me up. As we talked, she mentioned in passing that the most effective way to gauge the quality of a newborn’s latch is to have him latch on to someone who knows what a good latch feels like. Interesting, I thought, and filed it away.

The following day, another friend Heather came to visit with her eight-month-old daughter in tow. She was visibly shaken by the sight of our shrivelled infant. “Do you want me to nurse him?” she asked softly, all trace of her usual cerebral irony vanished. This caught me by surprise – it had not occurred to me that another woman might nurse for me – and I quickly said no. Out of propriety, I suppose. Or denial. Or closed-mindedness. Or all three.

Out of propriety, I suppose. Or denial. Or closed-mindedness. Or all three.

For most of human history, wet nurses were exceedingly common. The best of the best made an excellent living as highly prized employees. Sisters and good friends nursed each other’s babies as a matter of convenience. But 100 years of aggressive formula marketing has effectively erased the tradition of women helping each other in this way. I had never heard of anyone I knew nursing another woman’s child, or having her child nursed by another woman, and I had never wondered why. I sat in the rocking chair that night, nipples on fire, inconsolable shrunken baby looking more and more like a plucked chicken in my arms, and a terrible new panic hit me: we were in very serious trouble and could not go on this way.

Miranda with Elisa’s son, left, and her own: ‘I handed the baby to her and collapsed into a nearby chair to sob.’ Photograph: Courtesy of Elisa Albert“Call Miranda,” my husband said when the sun rose. Without hesitation, without my even fully articulating a thing, she said, simply, “Come over.”

Without hesitation, without my even fully articulating a thing, she said, simply, “Come over.”

We rushed over. I handed the baby to her and collapsed into a nearby chair to sob and thank her and sob and thank her, over and over again. The baby drank and drank and drank. His latch was indeed shallow, but she had a surfeit of compensatory milk. The relief was indescribable. I took a photograph, which felt absurd and vaguely exploitative, but I didn’t know what else to do with myself. Taking that picture was the most uncomfortable thing about the scene: I had unwittingly sensationalised what was a very simple, very personal, altogether quiet moment. A sacred thing. Photographing it, calling attention to it in that way, made it seem fleetingly indecent. Wrong.

Ten minutes later, my baby slept deeply. I felt, for the first time since the night he was born, that everything was going to be OK. I could feel my body unclench, my breathing slow and deepen, my mind quiet. My son had nursed well and was now peaceful in my arms. Miranda acted like it was no big deal. The idea that women have a hair-trigger for jealousy, that we despise each other as a matter of course, is a toxic hangover from adolescence. I felt no envy when I saw Miranda nurse my son. I longed to be able to nurse my baby, but I only felt fortunate that someone else could and did. I wondered aloud why we hadn’t just done this sooner. I kicked myself for waiting so long. Miranda laughed. “You weren’t ready,” she shrugged. We lay on the floor with the babies. Our husbands brought us tea.

Miranda acted like it was no big deal. The idea that women have a hair-trigger for jealousy, that we despise each other as a matter of course, is a toxic hangover from adolescence. I felt no envy when I saw Miranda nurse my son. I longed to be able to nurse my baby, but I only felt fortunate that someone else could and did. I wondered aloud why we hadn’t just done this sooner. I kicked myself for waiting so long. Miranda laughed. “You weren’t ready,” she shrugged. We lay on the floor with the babies. Our husbands brought us tea.

Where matters of the heart are concerned, I had been rather unlucky with regard to women. My relationship with my own mother is a challenging work-in-progress. I always had my share of friends, some of them good, but rarely did I feel I could trust women completely. Inevitably, it seemed, there was a hefty serving of cliquishness with a side of subverted rage. It didn’t help that I seemed to want so much more from women than I ever wanted from men – I wanted the world. So I was often that much more disappointed.

So I was often that much more disappointed.

I had adored the midwife’s arrogance when she first dropped by for prenatal exams. She acted as if birth was no big deal, and I wanted to impress her, to earn her respect, by taking on the same attitude. But it turned out that birth is a big deal. Not because it’s necessarily pathological, but because we are so fundamentally vulnerable, and because how we’re treated when we’re vulnerable can alter us profoundly, for better or for worse. What a stupid cosmic joke: I’d picked a “cool” midwife who turned out to embody the coldness and disrespect I wanted to avoid by giving birth at home. I was stunned to have made so colossal an error in judgment. Cool, it turned out, is not a useful character trait in a midwife (or in anyone, when it comes down to it). Having been let down by the midwife haunted me.

Miranda continued to nurse for me, so casually, it went almost without saying. I finally found a lactation consultant whose advice made sense. I supplemented with formula until I got nursing on track, which took three months, biweekly follow-ups, a hospital-grade rental pump, and a level of determination and commitment I was proud to discover I had. Never mind that my struggle called forth a certain hostility in some: as though I was fomenting some bullshit “mummy war” by insisting – at great cost and effort – on the simple act of nursing my baby. I was supposed to accept that, because breastfeeding was exceedingly difficult, I could not do it. I was supposed to concede to that potent cocktail of bad advice that devalues the functional power of the female body. To which I said, and still say: no.

‘The last thing I needed was to be entertaining guests who seemed embarrassed and uncomfortable when I nursed.’ Photograph: Courtesy of Elisa AlbertIt turned out that Miranda knew Maddy, a college friend I hadn’t seen in ages. Maddy happened to live a few blocks away, and had a new baby as well. She invited us all over, and we huddled in her living room, lined up the babies on a blanket, shared our stories, giggled, catnapped, stretched and ordered food. When it was time to go, Maddy handed me several bags of breast milk from her freezer. I had been putting in many hours at the miserable altar of the breast pump, so I knew exactly what it meant to give away those bags.

Maddy happened to live a few blocks away, and had a new baby as well. She invited us all over, and we huddled in her living room, lined up the babies on a blanket, shared our stories, giggled, catnapped, stretched and ordered food. When it was time to go, Maddy handed me several bags of breast milk from her freezer. I had been putting in many hours at the miserable altar of the breast pump, so I knew exactly what it meant to give away those bags.

Talking things through with these women – the mind-blowing experience of birth; the bad midwife; the free-floating anxiety that can take hold when you have no ballast; the pressure to accept “expert” opinion in lieu of advocating for yourself; the work of nursing, the value of nursing; the deep and wilful isolation of women from each other, of women from ourselves; this for ever altered landscape – I began to feel like a warrior, not a victim. We were sisters, and we traded our stories of valour and courage and survival and persistence. Being seen and heard by sympathetic women was more than a great comfort: it was sustaining, urgent and eminently sane.

In the years that followed, I became fascinated with the rights of the childbearing woman, consumed by the many ways in which women are often betrayed by the very people they’ve chosen to help them through this most profound transition. I trained as a childbirth and postpartum doula. I began to understand women better – that there are those of us who have a nurturing resource in our own mother, and those who do not; those who can talk about inhabiting their bodies, and those who cannot; those who are open about their struggles and ambivalence, and those who feign control; those who are lucky enough to be loved and cared for in vulnerability, and those who are not; those who want to line up the babies on a blanket and sit and cook and stretch and talk, and those who do not.

When my oldest brother died young, some people showed up, planted themselves beside me, welcomed my laughter and tears in equal measure – and some did not. Some seemed capable of sitting with it – life, death – and some would do anything to avoid it. The former were worth holding fast; the latter, not so much. Responses to birth and postpartum seemed uncannily similar.

The former were worth holding fast; the latter, not so much. Responses to birth and postpartum seemed uncannily similar.

I’ve often thought about writing to my midwife, especially after I met not one, not two, but three other women whom she had similarly neglected. The first unattended woman had developed a swollen cervix from pushing too soon, and wound up in hospital, where she’d delivered by emergency surgery. The second and third had given birth unassisted before the midwife showed up. I had been lucky by comparison.

I longed to be able to nurse my baby, but I felt lucky someone else could. Why hadn’t we done it sooner?‘I half-expected Miranda to lord it over me, having been so strong and capable when I was so incapable, so broken.’ Models: Isabella and Daniel from kitschagency.com. Babystart wooden highchair, £49.99, argos.co.uk. Photograph: Perou/The Guardian

Did you have postnatal depression, people wonder. And I shrug. I roll my eyes. I say no. Because it sounds like putting a stupid pink ribbon on post-traumatic stress disorder. And the last thing I wanted was to be medicated. Medicating women for quite reasonable emotional responses to quite unreasonable situations seems backwards. I needed a maternal figure, a dedicated and present midwife, dear and loving friends. I was blessed with one out of three. It could have been worse.

Because it sounds like putting a stupid pink ribbon on post-traumatic stress disorder. And the last thing I wanted was to be medicated. Medicating women for quite reasonable emotional responses to quite unreasonable situations seems backwards. I needed a maternal figure, a dedicated and present midwife, dear and loving friends. I was blessed with one out of three. It could have been worse.

The only people I know who did just fine in the postpartum period are those who score the triumvirate: well cared for in birth, surrounded by supportive peers, helpful elders to stay with them for a time. The others, wild-eyed at the supermarket, prone to tears, unable to nurse or sleep or breathe, a little too eager to make friends at baby groups – I can spot them at 20 paces. We form a vast and sorry club.

It took me a long time to regain my confidence. The state of early motherhood was in many ways a state of crisis, and although my husband was characteristically stalwart and kind, a full partner in every sense, it was the women who calmly, lovingly took my hand and led me through. It turned out I didn’t have to feign invulnerability whatsoever. The more vulnerable I remained, the clearer my vision became, and what I could see, at long last, was a circle of woman comrades, offering me fortitude and nourishment when I was bereft of all. My gratitude only grows with time.

It turned out I didn’t have to feign invulnerability whatsoever. The more vulnerable I remained, the clearer my vision became, and what I could see, at long last, was a circle of woman comrades, offering me fortitude and nourishment when I was bereft of all. My gratitude only grows with time.

Truthfully, I half-expected Miranda to lord it over me, having been so strong and capable and overflowing when I was so incapable, so broken. Instead, we have the kind of friendship that is warm, genuine and immune to distance or the passage of time. When we’re together, I take a special pleasure in the way she looks at my son: with affection and pride. He is a little bit hers, too.

Elisa Albert’s novel After Birth is published next month by Chatto & Windus at £16.99. To order a copy for £13.59, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Meet The Mother Who Breastfeeds Other People's Babies

Samantha Gadsden is a mother who breastfeeds other people’s babies – more of them than she can remember.

Over the past ten years, Samantha, a mother of four, has donated countless hours of time and plenty of breastmilk to other people’s babies.

Wet nursing was once a common practice; many women who were unable to feed their own babies would turn to wet nurses instead.

Wet nurses were women employed for the sole purpose of breastfeeding another person’s baby.

Historically, royal babies were given to wet nurses for feeding and this meant the practice remained popular amongst the upper classes.

You can read more about human donor milk sharing in Human Milk Banks – If They Save So Many Lives, Why Aren’t There More?

Since the introduction of infant formula, however, wet nursing has almost died out in most Western cultures.

Most modern mothers opt for infant formula if breastfeeding doesn’t work out. Some choose to use milk donated by other breastfeeding mothers, but very few women have the option, or the inclination, to use a wet nurse.

But you might be surprised to discover it still happens.

There are no official figures on the number of babies fed by wet nurses, though it is possible some parents rely on wet nurses but don’t discuss it publicly. Unfortunately, as with natural term breastfeeding and breastfeeding in public, unnecessary social stigma might be keeping the ancient practice of wet nursing as a ‘taboo’.

Samantha didn’t set out to become a wet nurse. In fact it was something she stumbled into almost by chance.

Her friend had to stay in hospital overnight with her toddler and needed somebody to look after her baby. Samantha didn’t think twice before agreeing to help out. She has since written about the experience on her blog.

Writing about the first feed, Samantha said:

‘He had a few test suckles and then settled down for a good long feed; my little one (aged nine months) wasn’t having that, so I had one on each breast – booby brothers. This brought back many happy memories of tandem feeding my three and five year olds. Having fed, he happily settled down and slept, waking only once for a feed and settling back off again.

Having fed, he happily settled down and slept, waking only once for a feed and settling back off again.

‘Late afternoon he went home to his mummy, who had missed him so – but he was happy and he was content. I would have him again in a heartbeat. I couldn’t bear to think of a baby sad and missing the usual comfort of the breast, when I was so easily able to provide that for him and lessen the worry for his already worried mum.

‘There is no ‘out there’ or ‘controversy’ for me. My friend and her baby needed me and, what is more, I enjoyed the time I spent with him; it was a pleasure for me. You forget so quickly how tiny they are and it was a privilege to be trusted with my friend’s most precious possession – her perfectly perfect baby boy’.

Samantha has since breastfed other babies in need. She wet nursed and donated milk to a friend, Gill, who had been diagnosed with cancer and was unable to continue breastfeeding.

Gill explained: “I badly wanted him to stay on breastmilk. He was wet nursed by Sam (and another lovely friend) and then we began the next six month journey of collecting stashes of donated milk from so many delightful mothers keen to help”.

He was wet nursed by Sam (and another lovely friend) and then we began the next six month journey of collecting stashes of donated milk from so many delightful mothers keen to help”.

To mothers in need, wet nursing can be invaluable. It’s often mothers who find themselves in unexpected situations who turn to wet nurses or milk donors for help. One such mother, Kayleigh, posted online when she was desperate for help after being rushed to hospital. Luckily for her, Samantha offered to help out.

Kayleigh said: “Elliot was formula intolerant and became quite ill, and Oliver was refusing anything that wasn’t from the breast. Sam turned up, and the babies latched on and fed well whilst their dad was out collecting breastmilk from milk donors. She even sent me a picture of them – happy and content, feeding away – to set my mind at ease during a difficult time … Samantha is an incredibly remarkable and selfless woman who continues to inspire me”.

Samantha works as a doula, providing prenatal, birth and postnatal support to families. The wet nursing isn’t part of her work, but rather an unpaid service she offers to those in need. She told BellyBelly all about her wet nursing adventures.

The wet nursing isn’t part of her work, but rather an unpaid service she offers to those in need. She told BellyBelly all about her wet nursing adventures.

“I found the babies did this really cute thing generally of taking a nipple, looking totally confused and almost shrugging their shoulders and realising it was all that was on offer and then just latching and suckling.

“I have also wet nursed once or twice just as a babysitter – never paid, although I don’t have an issue with people being paid, why not? The breastfeeding babysitting service might make things easier for new breastfeeding mums to catch a break, after their supply is established”.

If breast is best, then donor milk or wet nursing, as a brilliant second option for women unable to breastfeed, makes perfect sense.

Samantha told BellyBelly: “I do believe there is a need for more women to know they have options other than breast, expressing and formula. Even World Health Education guidelines put donor milk above formula”.

Recommended Reading:

Canadian Mother Breastfeeds Her Sick Sister’s Baby

Is it worth it to breastfeed children up to five years of age or even longer?

Subscribe to our ”Context” newsletter: it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright Getty Images

Should you breastfeed your children until the age of five or even longer?

29-year-old Englishwoman Emma Shardlow Hudson, who breastfeeds her five-year-old daughter and two-year-old son, sometimes at the same time, says it is good for their health and that they very rarely get sick due to "the presence of antibodies in milk."

The UK National Health System advises mothers to breastfeed their babies for as long as they both want to.

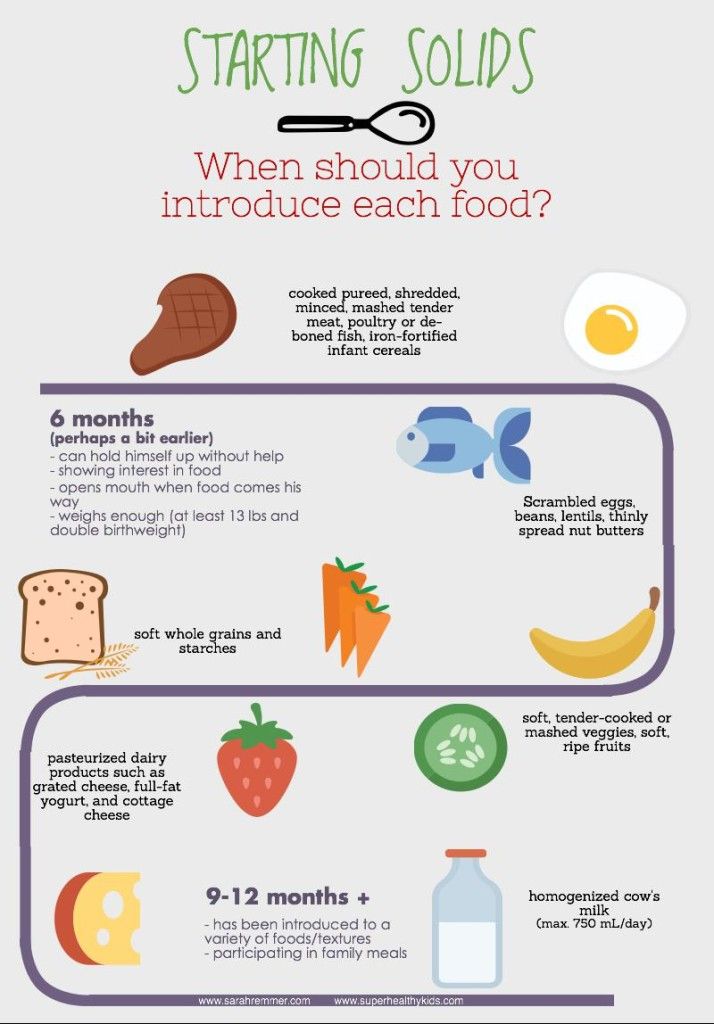

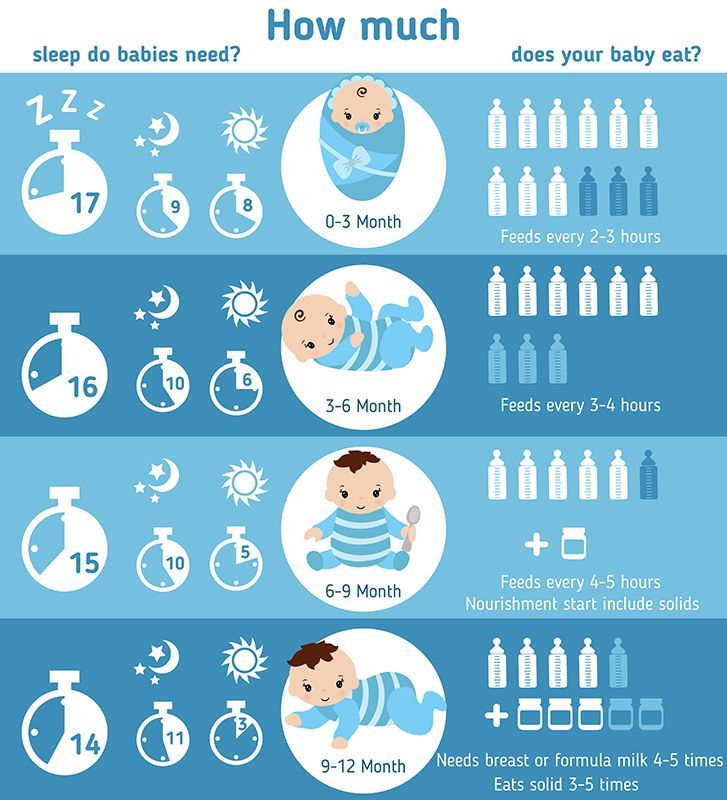

Women are generally advised to continue breastfeeding for only the first six months, and then gradually add solid foods to the baby's diet.

- Model breastfeeding photo sparks heated debate

- Politician breastfeeds her baby for the first time in the Australian Parliament

- Pregnancy and childbirth in Britain: free and without a doctor

British breastfeeding

In the UK, about 80% of mothers follow the advice to breastfeed their newborns after birth, but many stop doing so after a few weeks.

Only about a third of six-month-old babies are still getting their mother's milk, and by the first year of their life this figure drops to 0.5%.

According to a 2016 international survey, the UK has one of the world's lowest rates of breastfeeding women.

Experts say that many women simply find it difficult to start breastfeeding and often don't get the practical help they need in the first days after giving birth and with their first child when they're not yet breastfeeding.

In addition, many women feel uncomfortable doing this in public places and stop breastfeeding, switching to artificial feeding.

Is there anything better than breasts?

Experts agree that breastfeeding is good for the health of both the baby and the mother.

Breast milk protects the infant from infections, diarrhea and vomiting, and reduces the risk of obesity in adulthood.

For mothers, breastfeeding reduces the risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer in the future.

All this is good, but still - until what age should a child be breastfed?

At the moment there is not enough scientific evidence to answer this question unambiguously, so only general recommendations are offered to women.

"It is ideal to breastfeed a baby, along with other foods, until at least the start of the second year," says the UK National Health System website.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,After the first six months, solid foods other than milk can be gradually introduced to the baby

The World Health Organization believes that breastfeeding can continue at least until the baby is two of the year.

However, Dr. Max Davey of the British Royal Institute of Pediatrics and Child Health believes that there should be a limit to everything, and that breastfeeding should not be continued when it no longer provides any benefits.

"By the age of two, a child should be getting all the nutrients it needs from a normal diet, after that age, there is no additional health benefit from mother's milk," he says.

"It doesn't hurt anything"

Many factors influence a woman's decision to continue or stop breastfeeding. Much depends on whether the new mother returns to work, whether her friends and relatives support her, and how comfortable she feels with breastfeeding.

Also remember that breastfeeding often helps develop the emotional bond between mother and child.

"Breastfeeding is a very personal thing," says Dr. Davey.

"This can strengthen the relationship between mother and child, and in any case it will not cause harm, so people should do as they see fit."

Image copyright, Getty Images

But don't forget that some women find it physically difficult, if not impossible, to breastfeed, while others choose not to, for a variety of reasons, and experts say it's their choice. and should be treated with respect.

Breastfeeding twins and triplets

Being a mother of twins or triplets is a great joy, but also a challenge, especially in terms of breastfeeding. However, with proper support, breastfeeding twins is quite possible. Read more about this in our article.

Share this information

When you're expecting multiple babies, there's a lot to think about, feeding first. Organizing breastfeeding for twins or even triplets is a very difficult task. But be sure: it is possible, and the result will justify itself doubly.

Organizing breastfeeding for twins or even triplets is a very difficult task. But be sure: it is possible, and the result will justify itself doubly.

Like any breastfeeding mother, you need to understand the basic principles of breastfeeding: how milk production depends on consumption, how to find the right position and help babies latch on.

Additional difficulties in breastfeeding multiple babies are associated with time (more precisely, its absence), maintaining the mother's physical strength and finding the optimal feeding pattern. Solving these problems will be easier with someone's support.

How to prepare for breastfeeding twins?

The main thing is to start preparing before the birth. Even if you've breastfed before, talk to an expert about feeding twins.

You can attend special courses for pregnant women, and a lactation consultant or supervising doctor can teach you the basic principles of twin care and answer any questions. In addition, it will be useful to talk to mothers of twins and find information about small and large communities dedicated to raising twins. These communities often host meetings, publish helpful articles, provide phone support, and offer other types of assistance.

These communities often host meetings, publish helpful articles, provide phone support, and offer other types of assistance.

Arrange in advance with family and friends to help around the house, ask them to take over cooking, cleaning and shopping responsibilities so that you can fully devote yourself to breastfeeding. Robin, a mother of four from Canada, says this is extremely important: “For the first two months, my mother-in-law lived with us. I can’t imagine what I would do without her!”

In addition, it is important to correctly understand what awaits you. You will have to learn how to breastfeed two children at the same time, you will not sleep much, and at first you will not have time to leave the house at all.

“Life is going to be pretty stressful at first: get ready to dedicate all your time to breastfeeding,” warns Helen Tourier, head of support at the British Twins and Triplets Care Association (Tamba), a professional nurse and mother of three children, including twins. Feeding may take longer, especially if the babies have spent some time in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Feeding may take longer, especially if the babies have spent some time in the neonatal intensive care unit.

How to start breastfeeding twins?

The best way to start breastfeeding successfully is to ensure skin-to-skin contact with babies as soon as possible after delivery. 1 Include this in your birth plan and discuss your intention to breastfeed with your partner and healthcare providers ahead of time. Consider what to do if babies are born prematurely or are admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Ideally, breastfeeding should begin immediately after delivery, even after a caesarean section. Doctors should bring you babies and teach you how to properly attach them to the breast. If they haven't, ask for it and be sure to involve your partner so they know how to help you.

“I think the main reason I was successful with breastfeeding my twins, despite previously having difficulty feeding my oldest son, was the help of the maternity hospital experts during those critical early days,” says Zoe, mother of three from Great Britain.

Will I have enough milk for two babies?

Yes. The more babies you feed, the more milk is produced. Research shows mothers of triplets can produce three liters of milk a day0117 2 , despite the fact that the average baby boy needs 831 ml of milk per day. 3

After you give birth, you will begin to produce enough colostrum (nutrient-rich first milk) to feed newborn babies for the first two to four days. After that, the production of milk will take place on the principle of supply and demand.

Focus on the needs of the little ones. Breastfeed as soon as you notice any signs of hunger in any of them - babies may begin to wake up, stick out their tongue, turn their heads, grunt, lick their lips, suck their fingers. This will help your body produce enough milk.

How to make breastfeeding twins easier?

You and your little ones will have to learn by trial and error. One baby may latch on better, eat more often, or gain weight faster than another. Remember that every baby is unique. If you have any difficulties or doubts, contact a specialist.

Remember that every baby is unique. If you have any difficulties or doubts, contact a specialist.

“An obstetrician I know helped me for a long time to find the right position so that the babies would latch on correctly, — one of my daughters had problems with this at first,” says Anna, a mother of two children from the UK, “In the first month, I really needed help during feeding - at least in order to give me babies. It's hard to handle two babies at the same time, especially when they're so small."

Remember, the first weeks are the hardest. Feeding will not always be such a long and tiring process. And don't forget that breast milk, in any quantity, brings enormous health benefits to your babies.

If you are unsure if you can make do with breastfeeding alone, or if babies are not gaining enough weight on breastmilk, discuss feeding options with your healthcare provider, lactation consultant or healthcare provider, and your partner to make the best decision together for your family.

Comfort and proper attachment to the breast is the key to successful feeding. Use a special breastfeeding pillow to find the optimal position and relieve stress on your wrists, arms, shoulders and back.

Although all your energy and attention will be devoted to babies, do not neglect your own nutrition and health.

Bethan, a British mother of two, advises: “Try to get as much sleep as possible. Order groceries online and schedule delivery when family or friends are home. Prepare a large bottle of water and drink at every feeding. Ask relatives to take the children away after feeding so that you can rest.

What if babies cannot suckle?

If one or both babies need hospitalization or were born prematurely, breastfeeding is still possible, but will have to wait. If babies cannot latch on, you can express milk for them. So you can start and establish the production of milk, and your babies will receive all the useful substances that it contains. Your healthcare provider will help you learn how to feed with a syringe, tube, or other method. It is necessary to express milk according to the breastfeeding schedule - every two to three hours for about the first month. 4

It is necessary to express milk according to the breastfeeding schedule - every two to three hours for about the first month. 4

“I had a C-section at 30 weeks, and my twin girls spent several weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit,” recalls Monika, mother of three children from Switzerland, “We were able to start breastfeeding only at 34 weeks. 35 weeks. So for the first month, I pumped milk every day—at least eight times a day. I felt that this was the most important thing I could do for them.”

One of your babies may be strong enough to breastfeed on his own, while the other needs expressed milk. In this situation, many mothers prefer to express milk for a weak baby at the same time as feeding a strong one.

Breast milk has been shown to reduce the risk of serious illnesses that preterm infants are more susceptible to, including necrotizing enterocolitis and sepsis. 5 So if your babies are getting even a little expressed breast milk, know that you have created the best conditions for them.

How to feed twins: together or separately?

Each option has its own advantages. Until you get comfortable, it is worth feeding the babies separately, and then switch to pair feeding to save time.

There are many positions for breastfeeding twins, such as under the arm (one baby under one arm, the other under the other), parallel (both babies lie across the mother's body with their heads in the same direction) or lying down (both babies lie on the mother's stomach) . Ask a lactation consultant or supervising doctor to show you these poses. Perhaps you will like one of them or you will use different poses in different situations.

“It was easier for me to feed my twins at the same time,” says Zoe, a mother of three from the UK, “I also fed both at night at night. If one woke up for feeding, the husband woke up the second.

It may be more convenient for you to feed the babies separately when they ask, or to wake the second one after feeding the first one. And you can combine all three options.

And you can combine all three options.

Breastfeeding two babies at the same time in public is not easy, but for this case you can buy special capes so as not to be embarrassed.

“However, pair feeding of two babies is not for everyone. It happens that when one takes a breast, the second one throws, - says Robin, a mother of four children from Canada, - It just drove me crazy. It ended up that I began to feed in turn. Yes, it took more time, but I was calm.”

Some mothers assign each baby a specific breast and feed from that breast all the time. But it is much more useful to rotate the mammary glands in case one produces more milk than the other. Such a problem may arise in the early days, especially if one of the babies is weaker. In rotation, the stronger baby will stimulate the weaker baby to produce milk, so that sooner or later both breasts will produce the same amount of milk.

Breastfeeding multiple babies is very difficult for me. What to do?

Don't be afraid to ask your loved ones to take care of you so that you can take care of your little ones. "Sometimes coping means not taking on what you can't handle," says Bethan, a UK mom of two.

"Sometimes coping means not taking on what you can't handle," says Bethan, a UK mom of two.

Seek psychological support and expert help at any stage of breastfeeding.

“My self-control left me at the sixth week,” recalls Billy, a mother of four from the UK, “I called the hotline and went to the breastfeeding support group, where I was recommended more comfortable positions. I don't regret it at all."

Most importantly, don't blame yourself if something doesn't work out for you. Breastfeeding multiple babies can sometimes seem like a daunting task.

“Breastfeeding one baby takes a lot longer than you might think. The main thing is to stay calm, - says Olivia, mother of four children from Australia, - And it takes much more patience to feed two children. But the result is worth it."

Literature

1 Crenshaw JT. Healthy birth practice# 6: Keep mother and baby together - it's best for mother, baby, and breastfeeding. J Perinat Educ . 2014;23(4):211. — Crenshaw, JT, "Physiological Birthing Practices #6: Mother and Baby Should Be Together - Better for Mother, Baby, and Breastfeeding." J Perinat Eduk (Perinatal education). 2014;23(4):211.

2014;23(4):211. — Crenshaw, JT, "Physiological Birthing Practices #6: Mother and Baby Should Be Together - Better for Mother, Baby, and Breastfeeding." J Perinat Eduk (Perinatal education). 2014;23(4):211.

2 Flidel - Rimon Breast feeding twins and high multiples.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Edn. 2006;91(5):F377-F380. — Fidel-Raymond O., Shinwell I.S., "Breastfeeding Twins, Triplets, etc." Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Edn. 2006;91(5):F377-F380.

3 Kent JC et al. Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e387-395.- Kent JS et al., "Amount and frequency of breastfeeding and fat content of breast milk during the day." Pediatrix (Pediatrics). 2006;117(3): e 387-95.

4 Kent JC Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production.