Breast feeding a baby with acid reflux

Reflux | Breastfeeding Challenges | Start for Life

Breastfeeding challenges

There may be times when breastfeeding is challenging. Never ignore any issues you may have – talk to your health visitor, midwife, GP or breastfeeding specialist as soon as possible, they will be able to help you sort it out quickly.

Here are some common breastfeeding issues, and tips on what to do.

- Colic

- Constipation

- Mastitis

- Milk supply

- Reflux

- Sore nipples

- Thrush

- Tongue-tie

Baby reflux

If your baby brings up milk, or is sick during or after feeding, this is known as reflux. Reflux, also called posseting or spitting up, is quite common and your baby should grow out of it, usually by the time they are 12 months old.

What causes baby reflux?

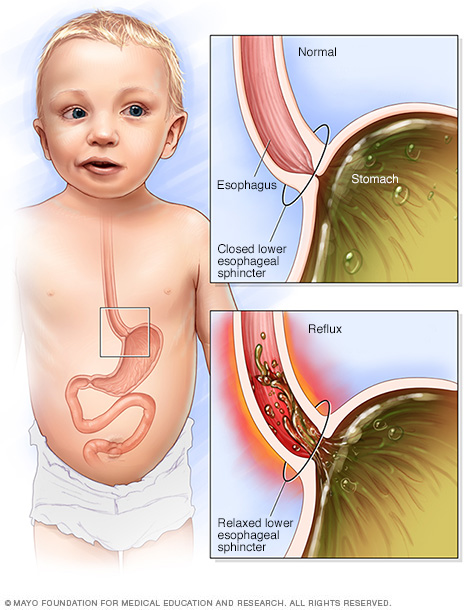

The muscle at the bottom of the food pipe acts as a kind of door into the stomach – so when food or milk travels down, the muscle opens allowing the food into the stomach.

However, while this muscle is still developing in the first year, it can open when it shouldn't (usually when your baby's tummy is full) allowing some food and stomach acid to travel back up again. Acid in the stomach is normal and a necessary part of the digestion process – it helps break down food.

In most babies, reflux is nothing to worry about as long as they are healthy and gaining weight as expected.

Baby reflux symptoms

- Constant or sudden crying when feeding.

- Bringing up milk during or after feeds (regularly).

- Frequent ear infections.

- Lots of hiccups or coughing.

- Refusing, gagging, or choking during feeds.

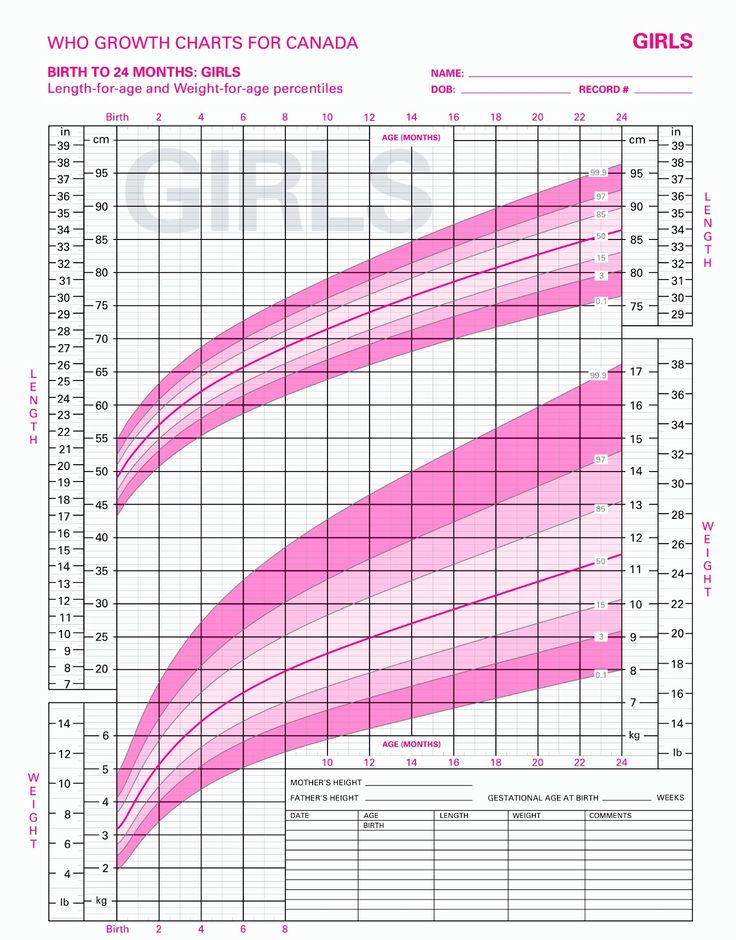

- Poor weight gain.

- Waking up at night a lot.

GORD

When reflux becomes painful and it happens frequently, this is known as 'gastro-oesophageal reflux disease' (GORD). GORD is more serious than mild, everyday reflux. The strong stomach acid can irritate and make the food pipe sore and inflamed, which is painful for your baby and may result in them needing medication.

The main signs and symptoms of GORD in your baby are:

- spitting up frequently

- abdominal pain

- feeding difficulties

- seeming unsettled and grizzly after a feed

These symptoms can lead to your baby not gaining weight, or even losing weight.

Silent reflux

Silent reflux can be confusing as there are no obvious signs or clues (such as spitting up). It's when the food travels back up the food pipe – but it's swallowed rather than spat out so is harder to identify. But your baby may display similar symptoms to those of regular reflux.

Breastfeeding Friend from Start for Life

The Breastfeeding Friend, a digital tool from Start for Life, has lots of useful information and expert advice to share with you – and because it's a digital tool, you can access it 24 / 7.

Breastfeeding tips for babies with reflux

- Feeding little and often (smaller feeds stop their tummy getting too full).

- Burping them requently during feeds – have a look at our guide to burping your baby for techniques.

- Try a different feeding position – check out our our guide to breastfeeding positions.

- Keep your baby upright, for at least an hour after feeding, this should help keep the milk down.

If you are mixed feeding (combining breastmilk and formula feeds), have a look at our advice on bottle feeding and reflux.

When to see the GP

If your baby has difficulty feeding or refuses to feed, regularly brings milk back up and seems uncomfortable after a feed, talk to your pharmacist, GP, or health visitor. They'll be able to give you practical advice on how to ease the symptoms and manage it – they may also need to rule out other causes (such as cow's milk allergy).

It might be helpful to keep a record of when your baby feeds, with details of how often and how much your baby brings the food back up, and how often your baby cries or seems distressed. This will help your health visitor or GP decide if your baby needs treatment.

Spitting Up & Reflux in the Breastfed Baby • KellyMom.

com

comBy Kelly Bonyata, BS, IBCLC

© Paul Hakimata – Fotolia.com

My baby spits up – is this a problem?

Spitting up, sometimes called physiological or uncomplicated reflux, is common in babies and is usually (but not always) normal. Most young babies spit up sometimes, since their digestive systems are immature, making it easier for the stomach contents to flow back up into the esophagus (the tube connecting mouth to stomach).

Babies often spit up when they get too much milk too fast. This may happen when baby feeds very quickly or aggressively, or when mom’s breasts are overfull. The amount of spitup typically appears to be much more than it really is. If baby is very distractible (pulling off the breast to look around) or fussy at the breast, he may swallow air and spit up more often. Some babies spit up more when they are teething, starting to crawl, or starting solid foods.

Now infants can get

all their vitamin D

from their mothers’ milk;

no drops needed with

our sponsor's

TheraNatal Lactation Complete

by THERALOGIX. Use PRC code “KELLY” for a special discount!

Use PRC code “KELLY” for a special discount!

A few statistics (for all babies, not just breastfed babies):

- Spitting up usually occurs right after baby eats, but it may also occur 1-2 hours after a feeding.

- Half of all 0-3 month old babies spit up at least once per day.

- Spitting up usually peaks at 2-4 months.

- Many babies outgrow spitting up by 7-8 months.

- Most babies have stopped spitting up by 12 months.

If your baby is a ‘Happy Spitter’ –gaining weight well, spitting up without discomfort and content most of the time — spitting up is a laundry & social problem rather than a medical issue.

Some causes of excessive spitting up

- Breastmilk oversupply or forceful let-down (milk ejection reflex) can cause reflux-like symptoms, and usually can be remedied with simple measures.

- Food sensitivities can cause excessive spitting. The most likely offender is cow’s milk products (in baby’s or mom’s diet).

Other things to ask yourself: is baby getting anything other than breastmilk – formula, solids (including cereal), vitamins (fluoride, iron, etc.), medications, herbal preparations? Is mom taking any medications, herbs, vitamins, iron, etc.?

Other things to ask yourself: is baby getting anything other than breastmilk – formula, solids (including cereal), vitamins (fluoride, iron, etc.), medications, herbal preparations? Is mom taking any medications, herbs, vitamins, iron, etc.?

- Babies with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) usually spit up a lot (see below).

- Although seldom seen in breastfed babies, regular projectile vomiting in a newborn can be a sign of pyloric stenosis, a stomach problem requiring surgery. It occurs 4 times more often in boys than in girls, and symptoms usually appear between 3 and 5 weeks of age. Newborns who projectile vomit at least once a day should be checked out by their doctor.

My older baby just started spitting up more – what’s up?

Some older babies will start spitting up more after a period of time with little or no spitting up. It’s not unusual to hear of this happening around 6 months, though you also see it at other ages. If the spitting up is very frequent (particularly if baby does not seem well), consider the possibility of a GI illness.

If the spitting up is very frequent (particularly if baby does not seem well), consider the possibility of a GI illness.

If baby does not seem ill, then here are some possible causes:

- It’s unlikely that your baby has suddenly developed a sensitivity to something in your milk, unless there’s something really new in your diet or you’re eaten LOTS of a particular food very recently. Any foods that baby eats are more likely than mom’s foods to cause the spitting up. Has baby started solids recently or tried a new food? Are you or baby taking any new medications? Have you or baby started taking vitamins or changed your vitamins?

- Has baby been fussier than normal, and/or crying more lately? If so, he is probably swallowing more air than usual, which can cause the spitting up.

- Spitting up can be caused by teething. When teething, babies tend to drool more and often swallow a lot of that extra saliva – this can cause extra spitting up.

- A cold or allergies can result in baby swallowing mucus and spitting up more.

- Baby may be hitting a growth spurt and swallowing more air when he nurses, especially if he’s been “guzzling” lately.

- If you tend to have oversupply or a fast let-down, some moms see renewed symptoms (which can include spitting up) after a growth spurt.

Essentially, though, if your baby is healthy and doing well despite the spitting up — gaining well, having enough wet/dirty diapers — then this is a laundry problem rather than a medical issue.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

A small percentage of babies experience discomfort and other complications due to reflux – this is called Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. These babies have been termed by some as ‘Scrawny Screamers’ (as compared to the Happy Spitters). There seems to be a family tendency toward reflux. GERD is particularly common in preemies (due to their immaturity) and in babies with other health problems. GERD usually improves by 12-24 months.

Following are symptoms of GERD — there are varying degrees and need your doctor’s involvement to diagnose:

- Frequent spitting up or vomiting; discomfort when spitting up.

Some babies with GERD do not spit up – silent reflux occurs when the stomach contents only go as far as the esophagus and are then re-swallowed, causing pain but no spitting up.

Some babies with GERD do not spit up – silent reflux occurs when the stomach contents only go as far as the esophagus and are then re-swallowed, causing pain but no spitting up. - Gagging, choking, frequent burping or hiccoughing, bad breath.

- Baby may be fussy and sleep less due to discomfort.

Warning signs of severe reflux:

- Inconsolable or severe fussiness or crying associated with feedings.

- Poor weight gain, weight loss, or failure to thrive. Difficulty eating. Breast/food refusal.

- Difficulty swallowing, sore throat, hoarseness, chronic nasal/sinus congestion, chronic sinus/ear infections.

- Spitting up blood or green/yellow fluid.

- Sandifer’s syndrome: Baby may ‘posture’ and arch the neck & back to relieve reflux pain–this lengthens the esophagus and reduces discomfort.

- Breathing problems: bronchitis, wheezing, chronic cough, pneumonia, asthma, aspiration, apnea, cyanosis.

GERD may cause babies to either undereat (if they associate feeding with the after-feeding pain, or if it hurts to swallow) or overeat (because sucking keeps the stomach contents down in the stomach and because mother’s milk is a natural antacid).

Current information on reflux indicates that testing or treatment for reflux in babies younger than 12 months should be considered only if spitting up is accompanied by poor weight gain or weight loss, severe choking, lung disease or other complications. Per Donna Secker, MS, RD in the article Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, “The infant with significant reflux who seems to be growing well and has no other significant health problems benefits most from little or no therapy.”

When GERD is suspected, many doctors first try a trial of various reflux medications (without running tests), to see if the medications improve baby’s symptoms. If testing is done, a 24-hour pH probe study () is the current “gold standard” for reflux testing in babies; this is a procedure where a tube is placed down baby’s throat to measure the acid level at the bottom of the esophagus. A barium swallow (upper GI) is not so invasive (baby swallows a barium mixture, then an x-ray is taken) but is not really effective for diagnosing reflux in babies, since most babies will reflux when given barium. An upper GI will not identify whether baby’s stomach contents are higher in acid or if there has been any esophagus damage due to reflux, but it will show if there are any blockages or narrowing of the stomach valves that may be causing or aggravating the reflux. Additional tests may be recommended in certain circumstances (see the links below for additional information). In rare cases, when baby has very severe reflux that is not relieved by medication, surgery may be recommended.

An upper GI will not identify whether baby’s stomach contents are higher in acid or if there has been any esophagus damage due to reflux, but it will show if there are any blockages or narrowing of the stomach valves that may be causing or aggravating the reflux. Additional tests may be recommended in certain circumstances (see the links below for additional information). In rare cases, when baby has very severe reflux that is not relieved by medication, surgery may be recommended.

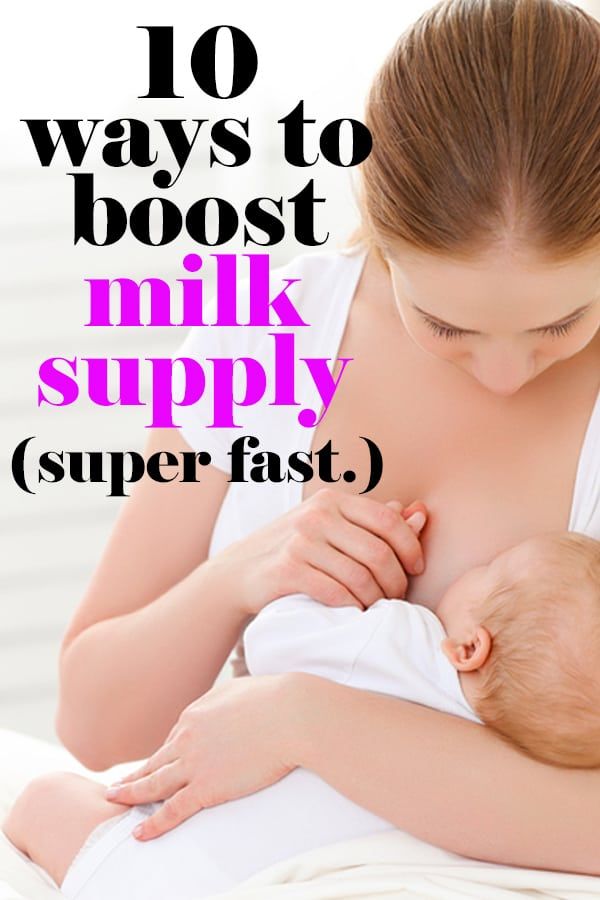

Breastfeeding Tips

- Aim for frequent breastfeeding, whenever baby cues to feed. These smaller, more frequent feedings can be easier to digest.

- Try positioning baby in a semi-upright or sitting position when breastfeeding, or recline back so that baby is above and tummy-to-tummy with mom. See this information on upright nursing positions.

- For fussy, reluctant feeders, try lots of skin to skin contact, breastfeeding in motion (rocking, walking), in the bath or when baby is sleepy.

- Ensure good latch to minimize air swallowing.

- Allow baby to completely finish one breast (by waiting until baby pulls off or goes to sleep) before you offer the other. Don’t interrupt active suckling just to switch sides. Switching sides too soon or too often can cause excessive spitting up (see Too Much Milk?). For babies who want to breastfeed very frequently, try switching sides every few hours instead of at every feed.

- Encourage non-nutritive/comfort sucking at the breast, since non-nutritive sucking reduces irritation and speeds gastric emptying.

- Avoid rough or fast movement or unnecessary jostling or handling of your baby right after feeding. Baby may be more comfortable when help upright much of the time. It is often helpful to burp often.

- As always, watch your baby and follow his cues to determine what works best to ease the reflux symptoms.

What can I do to minimize spitting up/reflux?

- Breastfeed! Reflux is less common in breastfed babies.

In addition, breastfed babies with reflux have been shown to have shorter and fewer reflux episodes and less severe reflux at night than formula-fed babies [Heacock 1992]. Breastfeeding is also best for babies with reflux because breastmilk leaves the stomach much faster [Ewer 1994] (so there’s less time for it to back up into the esophagus) and is probably less irritating when it does come back up.

In addition, breastfed babies with reflux have been shown to have shorter and fewer reflux episodes and less severe reflux at night than formula-fed babies [Heacock 1992]. Breastfeeding is also best for babies with reflux because breastmilk leaves the stomach much faster [Ewer 1994] (so there’s less time for it to back up into the esophagus) and is probably less irritating when it does come back up. - The more relaxed your infant is, the less the reflux.

- Eliminate all environmental tobacco smoke exposure, as this is a significant contributing factor to reflux.

- Reduce or eliminate caffeine. Excessive caffeine in mom’s diet can contribute to reflux.

- Allergy should be suspected in all infant reflux cases. According to a review article in Pediatrics [Salvatore 2002], up to half of all GERD cases in babies under a year are associated with cow’s milk protein allergy. The authors note that symptoms can be similar and recommend that pediatricians screen all babies with GERD for cow’s milk allergy.

Allergic babies generally have other symptoms in addition to spitting up.

Allergic babies generally have other symptoms in addition to spitting up. - Positioning:

- Reflux is worst when baby lies flat on his back.

- Many parents have found that carrying baby in a sling or other baby carrier can be helpful.

- Avoid compressing baby’s abdomen – this can increase reflux and discomfort. Dress baby in loose clothing with loose diaper waistbands; avoid “slumped over” or bent positions; for example, roll baby on his side rather than lifting legs toward tummy for diaper changes.

- Recent research has compared various positions to determine which is best for babies with reflux. Elevating baby’s head did not make a significant difference in these studies [Carroll 2002, Secker 2002, Craig 2004], although many moms have found that baby is more comfortable when in an upright position. The positions shown to significantly reduce reflux include lying on the left side and prone (baby on his tummy). Placing the infant in a prone position should only be done when the child is awake and can be continuously monitored.

Prone positioning during sleep is almost never recommended due to the increased SIDS risk. [Secker 2002]

Prone positioning during sleep is almost never recommended due to the increased SIDS risk. [Secker 2002] - Although recent research does not support recommendations to keep baby in a semi-upright position (30° elevation), this remains a common recommendation. Positioning at a 60° elevation in an infant seat or swing has been found to increase reflux compared with the prone (tummy down) position [Carroll 2002, Secker 2002].

- As always, experiment to find what works best for your baby.

- If your child is taking reflux medications, keep in mind that dosages generally need to be monitored and adjusted frequently as baby grows.

What about thickened feeds?

Baby cereal, added to thicken breastmilk or formula, has been used as a treatment for GER for many years, but its use is controversial.

Does it work? Thickened feeds can reduce spitting up, but studies have not shown a decrease in reflux index scores (i. e., the “silent reflux” is still present). Per Donna Secker, MS, RD in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, “The effect of thickened feedings may be more cosmetic (decreased regurgitation and increased postprandial sleeping) than beneficial.” Thickened feeds have been associated with increased coughing after feedings, and may also decrease gastric emptying time and increase reflux episodes and aspiration. Note that rice cereal will not effectively thicken breastmilk due to the amylase (an enzyme that digests carbohydrates) naturally present in the breastmilk.

e., the “silent reflux” is still present). Per Donna Secker, MS, RD in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, “The effect of thickened feedings may be more cosmetic (decreased regurgitation and increased postprandial sleeping) than beneficial.” Thickened feeds have been associated with increased coughing after feedings, and may also decrease gastric emptying time and increase reflux episodes and aspiration. Note that rice cereal will not effectively thicken breastmilk due to the amylase (an enzyme that digests carbohydrates) naturally present in the breastmilk.

Is it healthy for baby? If you do thicken feeds, monitor baby’s intake since baby may take in less milk overall and thus decrease overall nutrient intake. There are a number of reasons to avoid introducing cereal and other solids early. There is evidence that the introduction of rice or gluten-containing cereals before 3 months of age increases baby’s risk for type I diabetes. In addition, babies with GERD are more likely to need all their defenses against allergies, respiratory infections and ear infections – but studies show that early introduction of solids increases baby’s risk for all of these conditions.

The breastfeeding relationship: Early introduction of solids is associated with early weaning. Babies with reflux are already at greater risk for fussy nursing behavior, nursing strikes or premature weaning if baby associates reflux discomfort with breastfeeding.

Safety issues: Never add cereal to a bottle without medical supervision if your baby has a weak suck or uncoordinated sucking skills.

Additional Information

Spitting Up: Is it Reflux? by Anne Smith, IBCLC

LLL FAQ on breastfeeding and reflux

Gastroesophageal Reflux in Young Children by Pamela Tyler, M.S., CCC SLP

The Children’s Digestive Health and Nutrition Foundation (CDHNF)

NASPGHAN Guidelines on Pediatric GERD and Guidelines Summary on Pediatric GERD from the Children’s Digestive Health and Nutrition Foundation (CDHNF)

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN)

Bailey DJ, Andres JM, Danek GD, Pineiro-Carrero VM. Lack of efficacy of thickened feeding as treatment for gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr 1987 Feb;110(2):187-9.

Lack of efficacy of thickened feeding as treatment for gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr 1987 Feb;110(2):187-9.

Carroll AE, Garrison MM, Christakis DA. A Systematic Review of Nonpharmacological and Nonsurgical Therapies for Gastroesophageal Reflux in Infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:109-113.

Craig WR, Hanlon-Dearman A, Sinclair C, Taback S, Moffatt M. Metoclopramide, thickened feedings, and positioning for gastro-oesophageal reflux in children under two years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 Oct 18;(4):CD003502.

Ewer AK, Durbin GM, Morgan ME, Booth IW. Gastric emptying in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1994 Jul;71(1):F24-7. “On average, expressed breast milk emptied twice as fast as formula milk.”

Heacock HJ, Jeffery HE, Baker JL, Page M. Influence of breast versus formula milk on physiological gastroesophageal reflux in healthy, newborn infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992 Jan;14(1):41-6.

Iacono G, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow’s milk allergy in infants: a prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996 Mar;97(3):822-7.

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996 Mar;97(3):822-7.

Khorosheva EV, Sorvacheva TN, Kon’ IIa. Gastroesophageal reflux in nursing children: normal or pathology? Vopr Pitan. 2001;70(5):22-4.

Miyazawa R, Tomomasa T, Kaneko H, Tachibana A, Ogawa T, Morikawa A. Prevalence of gastro-esophageal reflux-related symptoms in Japanese infants. Pediatr Int. 2002 Oct;44(5):513-6.

Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997 Jun;151(6):569-72.

Omari TI, Rommel N, Staunton E, Lontis R, Goodchild L, Haslam RR, Dent J, Davidson GP. Paradoxical impact of body positioning on gastroesophageal reflux and gastric emptying in the premature neonate. J Pediatr. 2004 Aug;145(2):194-200.

Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Putnam PE. Thickened feedings as a cause of increased coughing when used as therapy for gastroesophageal reflux in infants. J Pediatr 1992 Dec;121(6):913-5.

J Pediatr 1992 Dec;121(6):913-5.

Orenstein SR. Prone positioning in infant gastroesophageal reflux: is elevation of the head worth the trouble? J Pediatr. 1990 Aug;117(2 Pt 1):184-7.

Parrilla Rodriguez AM, Davila Torres RR, Gonzalez Mendez ME, Gorrin Peralta JJ. Knowledge about breastfeeding in mothers of infants with gastroesophageal reflux. P R Health Sci J. 2002 Mar;21(1):25-9.

Ravelli AM, Tobanelli P, Volpi S, Ugazio AG. Vomiting and gastric motility in infants with cow’s milk allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001 Jan;32(1):59-64.

Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow milk allergy: is there a link? Pediatrics. 2002 Nov;110(5):972-84.

Sicherer SH. Clinical aspects of gastrointestinal food allergy in childhood. Pediatrics. 2003 Jun;111(6 Pt 3):1609-16.

Tobin JM, McCloud P, Cameron DJS. Posture and gastro-oesophageal reflux: a case for left lateral positioning. Arch Dis Child 1997;76:254-258.

Infant Reflux: Symptoms and Treatment

Search Support IconSearch Keywords

Home ›› What is Reflux in Infants?

Home ›› What is reflux in babies?

↑ Top

Signs and what to do

Post-feed regurgitation is a common occurrence in the first few months of life. This is usually harmless and completely normal, but parents should read about gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) in infants and how long it lasts to give them peace of mind.

This is usually harmless and completely normal, but parents should read about gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) in infants and how long it lasts to give them peace of mind.

We look at signs of reflux in babies, symptoms of different types of reflux, and how to help a child with signs of reflux. If you require further information, always contact your healthcare provider.

What is reflux in babies?

So we know reflux is common, but what causes reflux in babies? Because young children have not yet fully developed the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), that is, the muscle at the bottom of the esophagus that opens and closes to let food into the stomach and keep it there, food can easily pass back up the esophagus.

Acid reflux, also known as gastroesophageal reflux (GER), is a normal reflux that occurs in babies. This type of reflux is considered normal and occurs in 40-65% of babies.

How do I know if my child has acid (gastroesophageal) reflux?

If a baby is spitting up milk after a feed, it is most likely acid reflux. As babies get older, GER usually goes away on its own without any intervention. If a baby has complications beyond just spitting up a small amount of milk (such as feeding difficulties and discomfort), they may have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

As babies get older, GER usually goes away on its own without any intervention. If a baby has complications beyond just spitting up a small amount of milk (such as feeding difficulties and discomfort), they may have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Symptoms of GERD include:

- baby arching during or after feeding;

- crying more than three hours a day for no apparent reason;

- cough;

- gag reflex or difficulty swallowing;

- irritability, restlessness after eating;

- eating little or not eating;

- poor weight gain or loss;

- difficult breathing;

- severe or frequent vomiting.

GERD usually occurs when LES muscles are not toned in time, causing stomach contents to back up into the esophagus.

How do I know if my child has Laryngopharyngeal Reflux?

Another type of reflux, laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), also called silent reflux, is when the contents of the baby's stomach leak back into the larynx, the back of the nasopharynx. This type of reflux does not always cause external symptoms, which is why it is called "silent". Babies can have GERD and silent reflux at the same time, but their symptoms are somewhat different.

This type of reflux does not always cause external symptoms, which is why it is called "silent". Babies can have GERD and silent reflux at the same time, but their symptoms are somewhat different.

The following are some of the symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux:

- breathing problems;

- gag reflex;

- chronic cough;

- swallowing problems;

- hoarseness;

- regurgitation;

- poor weight gain or weight loss.

We have looked at the signs of reflux in infants, now we will move on to the treatment and duration of silent reflux in children, as well as the treatment of GERD.

How to deal with laryngopharyngeal reflux in babies while breastfeeding?

Breastfeeding mothers may need to review their diet if their babies show signs of reflux. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends breastfeeding mothers cut eggs and milk from their diet for two to four weeks to see if their baby's reflux symptoms improve or disappear. It may be worth eliminating acidic foods from your diet.

It may be worth eliminating acidic foods from your diet.

In most cases, GER and laryngopharyngeal reflux go away on their own. Typically, children outgrow reflux in the first year of life. If a child has persistent symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux, parents should consult a doctor. If your baby has severe vomiting, blood in the stool, or any of the symptoms of GERD listed above, parents should contact their pediatrician as soon as possible.

How can I help my child with reflux or GERD?

Reflux symptoms in babies usually go away on their own, but the following tips can help relieve symptoms:

- Thicken food with rice or a special milk thickener.

- Hold the bottle at an angle that fills the nipple completely with milk to reduce the amount of air your baby swallows. This can help prevent colic, gas, and reflux.

- Try the AirFree anti-colic bottle, designed to reduce air swallowing during feeding.

4. Let the baby burp during and after feeding. If the baby is bottle fed, parents can let him burp after every 30-60 ml. If the mother is breastfeeding, she may let the baby burp when changing breasts.

5. Hold baby upright after feeding. As a rule, in order for the milk to remain in the stomach, after feeding the baby, it is necessary to hold it in an upright position for 10-15 minutes. But, if the child has reflux, parents should keep him upright a little longer.

These tips may help relieve symptoms, but they do not replace a doctor's advice.

Parents should not change their infant formula formula without first talking to their healthcare provider.

Don't panic! Reflux is very common in babies during the first three months of life, and most babies outgrow it without any consequences. Although GERD is a slightly more serious condition, there are many treatments, ways to manage it, and help newborns. Feel free to contact your doctor with any questions or concerns you may have.

4 Seattle Children’s Hospital

5 The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases - Treatment for GER & GERD in Infants

Any links to third party websites that may be included on this site are provided solely as a convenience to you. Philips makes no warranties regarding any third party websites or the information they contain.

I understand

You are about to visit a Philips global content page

Continue

You are about to visit the Philips USA website.

I understand

Gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants. Information for patients.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the medical term for regurgitation (backward reflux) of stomach contents into the esophagus and (sometimes) the mouth. Since certain acids are normally found in the lumen of the stomach, GER is sometimes (especially abroad) called acid reflux.

Reflux is normal and occurs in healthy infants, children and adults. Most babies have brief episodes during which they spit up milk or breastfeeding formula through their mouth and/or nose. Uncomplicated reflux usually does not bother the child, has a low risk of developing chronic complications, and usually does not require treatment.

In contrast, children with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are whiny, gain weight more slowly, often have recurrent pneumonias, or hemoptysis. Children with these symptoms usually require further evaluation and treatment. Although most children with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms resolve on their own as they grow older, some children have these symptoms as they age.

What is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

When we eat, food passes into the esophagus and then into the stomach. The esophagus is made up of, among other things, special layers of muscle that expand and contract to push food into the stomach in a series of undulating movements: this is called the peristaltic movement of the esophagus.

At the bottom of the esophagus, where it joins the stomach, there is a ring of muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). When food reaches the LES, it relaxes to allow it to enter the stomach, and when food passes into the stomach, it closes to prevent food and stomach acid from refluxing back into the esophagus.

Sometimes this ring of muscle (LE) does not close completely, allowing fluid from the stomach to back up into the esophagus, this can happen in anyone but is most common in infants. Most of these episodes go unnoticed because reflux only affects the lower esophagus.

As the child grows, the angle between the stomach and esophagus increases, which leads to a sharp decrease in the frequency of reflux. Spitting stops completely in more than half of children by 10 months of age, 80 percent of children by 18 months of age, and 98 percent of children under the age of two.

Uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux Gastroesophageal reflux is very common in infants during the first months of life, approximately 50% of children aged 0-3 months have at least one regurgitation per day.

Babies who burp infrequently, eat enough food, have normal weight gain for their age, and don't have excessive tearfulness - so-called "uncomplicated" reflux. Such regurgitation is a consequence of the anatomical features of a child of this age, since the short esophagus and the tiny volume of the stomach contribute to the reverse flow of fluid from it. Frequent emptying of air from the stomach and limiting physical activity after feeding can reduce the frequency and amount of spitting up.

Children with uncomplicated reflux usually do not need further testing. If the symptoms increase, appear for the first time after six months of life, or do not decrease by the age of 18 to 24 months, the child should be shown to the pediatrician, and most likely will require a consultation with a gastroenterologist.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Simple reflux becomes gastroesophageal reflux disease when stomach acid begins to irritate or damage the esophagus. It occurs in a very small percentage of children who have frequent regurgitation. The onset of the disease is due to: a high frequency of refluxes, a large amount of refluxes, or the inability of the esophagus to quickly neutralize the acid thrown into it. Treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is directed at one or more of these factors.

The onset of the disease is due to: a high frequency of refluxes, a large amount of refluxes, or the inability of the esophagus to quickly neutralize the acid thrown into it. Treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is directed at one or more of these factors.

Some of the signs or symptoms that may indicate GERD include: refusal to eat, frequent crying and arching of the neck and back (as if in pain), aspiration during regurgitation, severe (fountain) vomiting, frequent coughing, or small gains in weight. These symptoms are not normal and require further testing to confirm the diagnosis of GERD or identify another diagnosis.

It is often difficult to tell if an infant is in pain. Usually a baby who cries from “banal” reasons can be consoled by distracting him, or by detecting and eliminating the factor that irritates him (wet diapers, hunger, desire to sleep, etc.).

Tearfulness and reflux. Many parents are concerned that reflux is the cause of their child's tearfulness or difficulty sleeping. However, clinical studies have shown that uncomplicated reflux does not usually cause pain, and lowering stomach acid does not reduce tearfulness.

However, clinical studies have shown that uncomplicated reflux does not usually cause pain, and lowering stomach acid does not reduce tearfulness.

Tearfulness and difficulty sleeping are not GERD-specific symptoms and may be due to a variety of causes. Children who have frequent regurgitation and severe tearfulness should be examined by a doctor. If there are no other problems, a milk-exclusion diet and food thickeners may be recommended for such an infant.

Diagnosis of GERD

If a child is suspected of having gastroesophageal reflux disease, the first step in the evaluation should be a history and physical examination. The need for further testing depends on what the doctor determines and may include the following tests:

- Laboratory testing (blood and/or urine)

- X-ray examination to assess the swallowing function of the infant and the anatomy of his stomach

- Endoscopy, to assess the condition of the esophagus

Treatment for GERD

Babies with uncomplicated reflux do not require any treatment, but some guidance can be given to parents to make lifestyle changes for these babies. Such recommendations usually include: avoiding overeating (eating more often and in smaller amounts), avoiding any exposure of the child to tobacco smoke, a diet with no milk, and food thickeners. We will call these measures conservative (as opposed to medical and surgical measures).

Such recommendations usually include: avoiding overeating (eating more often and in smaller amounts), avoiding any exposure of the child to tobacco smoke, a diet with no milk, and food thickeners. We will call these measures conservative (as opposed to medical and surgical measures).

Many children with reflux symptoms benefit from conservative measures. In one study, more than 80 percent of these children experienced complete or partial improvement in symptoms from conservative measures alone, such as food thickeners, avoidance of exposure to tobacco smoke, and reduced exposure to cow's milk protein (formulas based on partial protein hydrolysis, or complete exclusion of milk from the mother's diet if the child is breastfed).

Dairy-free diet. Studies show that 15 to 40 percent of children with gastroesophageal reflux disease have cow's milk protein intolerance, or "dietary, protein-induced gastroenteropathy." Diagnosis of this condition in most children is based on their symptoms, and the degree of positive response to changes in diet; laboratory studies are usually not necessary.

Most children with dietary protein-induced gastroenteropathy are intolerant of cow's milk protein alone, although some are also intolerant of soy proteins. To eliminate these proteins from a baby's diet, breastfeeding mothers should completely eliminate all dairy and soy products from their diet. In rare cases, it may be necessary to exclude other proteins from the mother's diet, but all this should happen only on the recommendation of the attending physician.

If a child's GERD symptoms improve after two to three weeks of the diet, it is advisable to continue the diet until the child is one year old. After this age, many children get rid of intolerance to milk proteins. If, after the diet is canceled, the symptoms return, the mother should return to the restrictions in her diet and the nutrition of the baby.

If the baby is formula-fed, a formula that does not contain milk and soy protein (hydrolysates) may be offered. On this diet, the child is observed for 1-2 weeks to determine if the child's reflux symptoms are improving. If symptoms do not improve, the child may be advised to return to the original formula.

If symptoms do not improve, the child may be advised to return to the original formula.

Almost all children with protein intolerance recover from it by the age of 1 year.

Food thickeners. An adapted formula with a thickener, or expressed breast milk with a thickener added, can help reduce the frequency of spitting up and relieve symptoms in a baby who is gaining well. In children under the age of three months, or children with allergies, thickeners can only be prescribed by a doctor. However, thickeners are not recommended as monotherapy (the only treatment) in infants whose esophagus is already damaged by acid reflux (i.e., children with esophagitis).

In the United States of America, substances derived from rice are commonly used as food thickeners, in other countries rice starch, corn and potato starch, carob flour, or carob bean gluten are often used. To thicken your baby's nutrition, one tablespoon of rice starch per 1 ounce (about 30 ml) of formula or expressed breast milk is usually used. The hole on the nipple of the bottle should be slightly larger than usual to allow the passage of thickened formula or breast milk. However, it should not be too large, so that the child does not choke if the mixture flows too quickly. If the doctor recommended feeding the child with thickeners, then the usual formula for the child, or expressed milk, is mixed immediately before feeding with a special baby thickener, which are sold in pharmacies. In addition, there are ready-made artificial mixtures containing thickeners in their composition.

The hole on the nipple of the bottle should be slightly larger than usual to allow the passage of thickened formula or breast milk. However, it should not be too large, so that the child does not choke if the mixture flows too quickly. If the doctor recommended feeding the child with thickeners, then the usual formula for the child, or expressed milk, is mixed immediately before feeding with a special baby thickener, which are sold in pharmacies. In addition, there are ready-made artificial mixtures containing thickeners in their composition.

Women who are breastfeeding are generally advised not to replace breast milk with formula, but rather to express and add a thickener. Breast milk itself has properties that help babies recover from GERD.

Body position. Babies may have fewer episodes of spitting up if they are upright and physically and mentally calm each time after feeding for 20 to 30 minutes after feeding (i.e. the infant should be carried on an adult's shoulder rather than laid to bed after feeding). Parents should avoid large amounts of feeding, and should interrupt feeding as soon as the infant begins to lose interest in food and become distracted.

Parents should avoid large amounts of feeding, and should interrupt feeding as soon as the infant begins to lose interest in food and become distracted.

Drug therapy for GERD. If the child's symptoms do not improve after the conservative treatment described above, drugs that reduce the acidity of gastric contents may be recommended. There are a number of medications available to treat heartburn in adults. However, it should be remembered that the safety and efficacy of these drugs in children is completely different.

Children with uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux (without esophagitis) should not be given drugs that reduce gastric acidity or gastric emptying rate.

Children with suspected GERD may have good symptomatic response with short courses of acid-blocking drugs. Omeprazole and lansoprazole have been best studied in infants. If after the appointment of these drugs there is no noticeable decrease in the manifestations of GERD, the course of treatment is most often interrupted.