Weston a price baby food

Nourishing a Growing Baby - The Weston A. Price Foundation

Read this in: ČeštinaDeutsch

🖨️ Print post

A Growing Wise Kids Column

Food is what nourishes the body and makes us healthy and strong–especially when one’s weight hovers around 20 pounds! Infant nutrition is critical for ensuring proper development, maximizing learning capacities and preventing illness. At no other time in life is nutrition so important. But which foods are best? The research clearly points in the direction of Weston A. Price Foundation principles.

Breast or Bottle

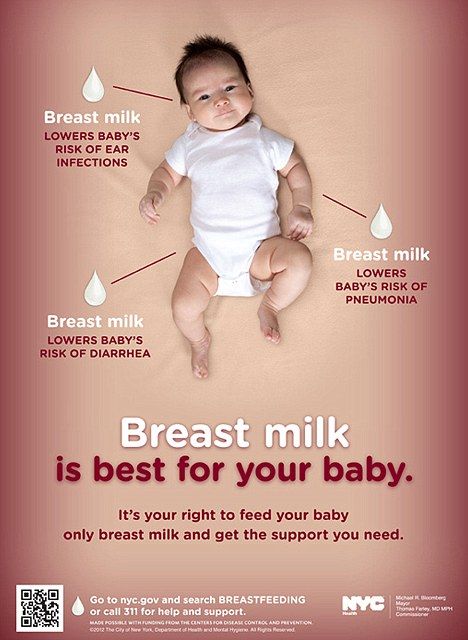

Numerous studies support the benefits of breastfeeding. For example, breastfed babies tend to be more robust, intelligent and free of allergies and other complaints like intestinal difficulties.1 Other studies have shown that breastfed infants have reduced rates of respiratory illnesses and ear infections.2,3 Some researchers believe breastfed infants have greater academic potential than formula-fed infants, which is thought to be due to the fatty acid DHA found in mother’s milk and not in most US formulas. 4

However, other studies show the opposite. In 2001, a study found breastfed children had more asthma than bottle-fed.5 A Swedish study found that breastfed infants were just as likely to develop childhood ear infections6 and childhood cancer as formula-fed babies.7

So, what is best for baby? It comes down to nutrition! Hands down, healthy breast milk is perfectly designed for baby’s physical and mental development, but this is only true when mom supplies her body with the right nutrients.

The typical modern diet is filled with products based on sugar, white flour, additives and commercial fats and oils, which do not nourish and build. The proper nutrients are necessary to create breast milk that will provide all a growing baby needs. These include good quality proteins from foods such as grass-fed meats and organ meats, good quality fats from butter, coconut oil, olive oil, cod liver oil and egg yolks, as well as complex carbohydrate-rich foods like vegetables, whole grains and legumes–think whole food, natural and seasonal, with a big emphasis on healthy fat.

Bottom line, in a perfect world, with perfect nutrition, every woman would breastfeed. Unfortunately, we don’t live in a perfect world. What about low milk supply, an unwell mother or adoption? Luckily, it is possible to make a wholesome whole food baby formula. (See FAQs on Homemade Baby Formula.)

After (or With) the Breast or Bottle

Ideally, breastfeeding should be maintained for a year, with a goal of six months for working mothers. The first year of life requires a full spectrum of nutrients, including fats, protein, cholesterol, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals. Once breast milk is no longer the sole source of these nutrients, where should one go?

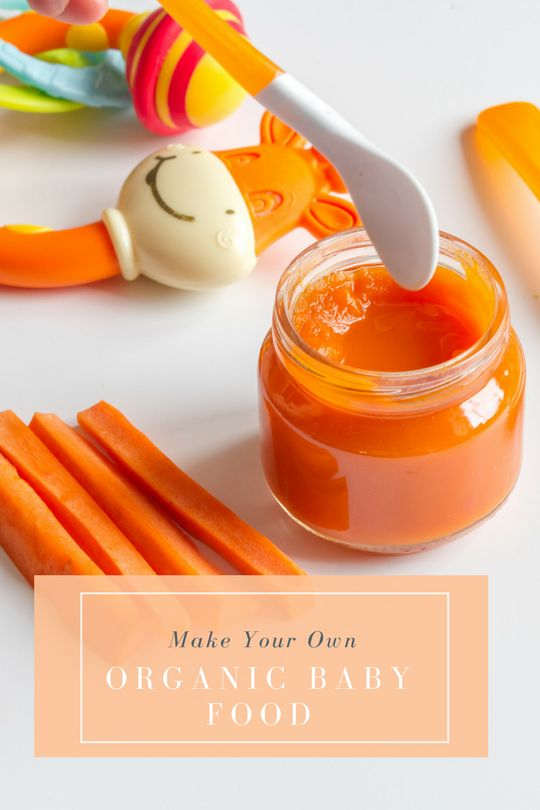

There are three concepts to keep in mind. First, make your little one a “whole foods baby”! Avoid processed and refined foods as much as possible, including many brands of baby food; they are usually devoid of nutrients and have added “undesirables.” It is always best to make your own baby food from organic, whole foods. (You can freeze it in one-serving sizes for later use.) Better-quality, additive-free, prepared brands of baby food, like Earth’s Best, do exist, but it is still better to make your own baby food to be assured of the quality–plus making baby food puts mom on the right track for home food preparation for the years to come.

(You can freeze it in one-serving sizes for later use.) Better-quality, additive-free, prepared brands of baby food, like Earth’s Best, do exist, but it is still better to make your own baby food to be assured of the quality–plus making baby food puts mom on the right track for home food preparation for the years to come.

Second, go slowly and be observant; every baby will have an individual response to different foods. Introduce new foods one at a time and continue to feed that same food for at least four days to rule out the possibility of a negative reaction. Signs of intolerance include redness around the mouth; abdominal bloating, gas and distention; irritability, fussiness, over-activity and awaking throughout the night; constipation and diarrhea; frequent regurgitation of foods; nasal and/or chest congestion; and red, chapped or inflamed eczema-like skin rash.8

Finally, respect the tiny, still-developing digestive system of your infant. Babies have limited enzyme production, which is necessary for the digestion of foods. In fact, it takes up to 28 months, just around the time when molar teeth are fully developed, for the big-gun carbohydrate enzymes (namely amylase) to fully kick into gear. Foods like cereals, grains and breads are very challenging for little ones to digest. Thus, these foods should be some of the last to be introduced. (One carbohydrate enzyme a baby’s small intestine does produce is lactase, for the digestion of lactose in milk.1)

In fact, it takes up to 28 months, just around the time when molar teeth are fully developed, for the big-gun carbohydrate enzymes (namely amylase) to fully kick into gear. Foods like cereals, grains and breads are very challenging for little ones to digest. Thus, these foods should be some of the last to be introduced. (One carbohydrate enzyme a baby’s small intestine does produce is lactase, for the digestion of lactose in milk.1)

Foods introduced too early can cause digestive troubles and increase the likelihood of allergies (particularly to those foods introduced). The baby’s immature digestive system allows large particles of food to be absorbed. If these particles reach the bloodstream, the immune system mounts a response that leads to an allergic reaction. Six months is the typical age when solids should be introduced,9,10,11 however, there are a few exceptions.

Babies do produce functional enzymes (pepsin and proteolytic enzymes) and digestive juices (hydrochloric acid in the stomach) that work on proteins and fats. 12 This makes perfect sense since the milk from a healthy mother has 50-60 percent of its energy as fat, which is critical for growth, energy and development.13 In addition, the cholesterol in human milk supplies an infant with close to six times the amount most adults consume from food.13 In some cultures, a new mother is encouraged to eat six to ten eggs a day and almost ten ounces of chicken and pork for at least a month after birth. This fat-rich diet ensures her breast milk will contain adequate healthy fats.14

12 This makes perfect sense since the milk from a healthy mother has 50-60 percent of its energy as fat, which is critical for growth, energy and development.13 In addition, the cholesterol in human milk supplies an infant with close to six times the amount most adults consume from food.13 In some cultures, a new mother is encouraged to eat six to ten eggs a day and almost ten ounces of chicken and pork for at least a month after birth. This fat-rich diet ensures her breast milk will contain adequate healthy fats.14

Thus, a baby’s earliest solid foods should be mostly animal foods since his digestive system, although immature, is better equipped to supply enzymes for digestion of fats and proteins rather than carbohydrates.1 This explains why current research is pointing to meat (including nutrient-dense organ meat) as being a nourishing early weaning food.

Is Cereal the Best First Food?

Remember, the amount of breast milk and/or formula decreases when solid foods are introduced. This decrease may open the door for insufficiencies in a number of nutrients critical for baby’s normal growth and development. The nutrients that are often in short supply when weaning begins include protein, zinc, iron and B-vitamins. One food group that has these nutrients in ample amounts is meat.

This decrease may open the door for insufficiencies in a number of nutrients critical for baby’s normal growth and development. The nutrients that are often in short supply when weaning begins include protein, zinc, iron and B-vitamins. One food group that has these nutrients in ample amounts is meat.

Unfortunately, cereal is the most often recommended early weaning food. A recent Swedish study suggests that when infants are given substantial amounts of cereal, they may suffer from low concentrations of zinc and reduced calcium absorption.15

In the US, Dr. Nancy Krebs headed up a large infant growth study that found breastfed infants who received puréed or strained meat as a primary weaning food beginning at four to five months grew at a slightly faster rate. Kreb’s study suggests that inadequate protein or zinc from common first foods may limit the growth of some breastfed infants during the weaning period. More importantly, both protein and zinc levels were consistently higher in the diets of the infants who received meat. 16 Thus, the custom of providing large amounts of cereals and excluding meats before seven months of age may short-change the nutritional requirements of the infant.17

16 Thus, the custom of providing large amounts of cereals and excluding meats before seven months of age may short-change the nutritional requirements of the infant.17

Meat is also an excellent source of iron. Heme iron (the form of iron found in meat) is better absorbed than iron from plant sources (non-heme). Additionally, the protein in meat helps the baby more easily absorb iron from other foods.18 Two recent studies19,20 have examined iron status in breastfed infants who received meat earlier in the weaning period. While researchers found no measurable change in breastfed babies’ iron stores when they received an increased amount of meat, the levels of hemoglobin (iron-containing cells) circulating in the bloodstream did increase. Meat also contains a much greater amount of zinc than cereals, which means more is absorbed.21 These studies confirm the practices of traditional peoples, who gave meat–usually liver–as the first weaning food. Furthermore, the incidence of allergic reactions to meat is minimal and lower still when puréed varieties are used.17,22,23,24

Furthermore, the incidence of allergic reactions to meat is minimal and lower still when puréed varieties are used.17,22,23,24

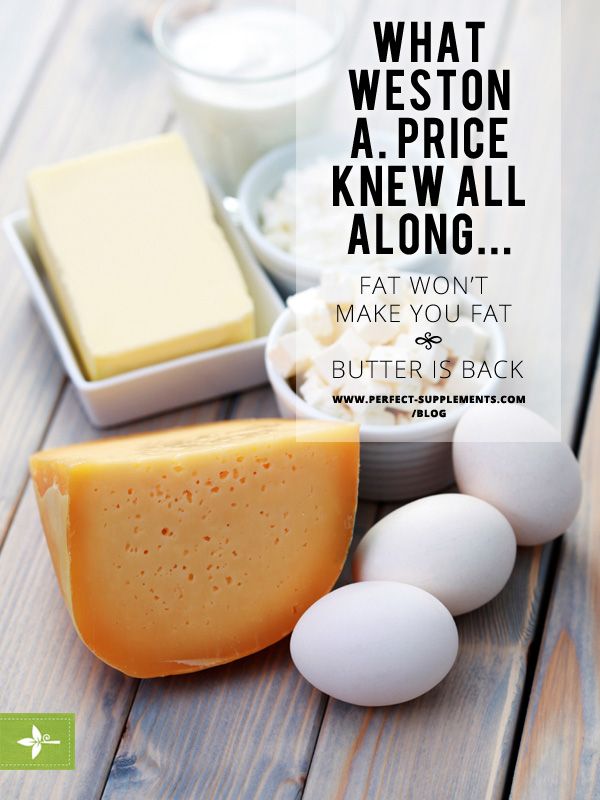

Don’t Fear Fats!

Pediatric clinicians have known for some time that children fed low-fat and low-cholesterol diets fail to grow properly. After all, a majority of mother’s milk is fat, much of it saturated fat. Children need high levels of fat throughout growth and development. Milk and animal fats give energy and also help children build muscle and bone.1 In addition, the animal fats provide vitamins A and D necessary for protein and mineral assimilation, normal growth and hormone production.27

Choose a variety of foods so your child gets a range of fats, but emphasize stable saturated fats, found in butter, meat and coconut oil, and monounsaturated fats, found in avocados and olive oil.

Foods to Introduce

Egg yolks, rich in choline, cholesterol and other brain-nourishing substances, can be added to your baby’s diet as early as four months,1 as long as baby takes it easily. (If baby reacts poorly to egg yolk at that age, discontinue and try again one month later.) Cholesterol is vital for the insulation of the nerves in the brain and the entire central nervous system. It helps with fat digestion by increasing the formation of bile acids and is necessary for the production of many hormones. Since the brain is so dependent on cholesterol, it is especially vital during this time when brain growth is in hyper-speed.25 Choline is another critical nutrient for brain development. The traditional practice of feeding egg yolks early is confirmed by current research. A study published in the June 2002 issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition compared the nutritional effects of feeding weaning infants 6-12 months of age regular egg yolks, enriched egg yolks, and an otherwise normal diet. The researchers found that both breastfed and formula-fed infants who consumed the egg yolks had improved iron levels when compared with the infants who did not.

(If baby reacts poorly to egg yolk at that age, discontinue and try again one month later.) Cholesterol is vital for the insulation of the nerves in the brain and the entire central nervous system. It helps with fat digestion by increasing the formation of bile acids and is necessary for the production of many hormones. Since the brain is so dependent on cholesterol, it is especially vital during this time when brain growth is in hyper-speed.25 Choline is another critical nutrient for brain development. The traditional practice of feeding egg yolks early is confirmed by current research. A study published in the June 2002 issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition compared the nutritional effects of feeding weaning infants 6-12 months of age regular egg yolks, enriched egg yolks, and an otherwise normal diet. The researchers found that both breastfed and formula-fed infants who consumed the egg yolks had improved iron levels when compared with the infants who did not. In addition, those infants who got the egg yolks enriched with extra fatty acids had 30 percent to 40 percent greater DHA levels than those fed regular egg yolks. No significant effect on blood cholesterol levels was seen.26

In addition, those infants who got the egg yolks enriched with extra fatty acids had 30 percent to 40 percent greater DHA levels than those fed regular egg yolks. No significant effect on blood cholesterol levels was seen.26

Thus, the best choice for baby is yolks from pasture-fed hens raised on flax meal, fish meal, or insects since they will contain higher levels of DHA. Why just the yolk? The white is the portion that most often causes allergic reactions, so wait to give egg whites until after your child turns one.1,11

Don’t neglect to put a pinch of salt on the egg yolk. While many books warn against giving salt to babies, salt is actually critical for digestion as well as for brain development. Use unrefined salt to supply a variety of trace minerals.

Around four months is a good time to start offering cod liver oil, which is an excellent source of the omega-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA (also important for brain develoment) as well as vitamins A and D. Start with a 1/4 teaspoon of high-vitamin cod liver oil or 1/2 teaspoon regular dose cod liver oil, doubling the amount at 8 months.12 Use an eye dropper at first; later baby can take cod liver oil mixed with a little water or fresh orange juice.

Start with a 1/4 teaspoon of high-vitamin cod liver oil or 1/2 teaspoon regular dose cod liver oil, doubling the amount at 8 months.12 Use an eye dropper at first; later baby can take cod liver oil mixed with a little water or fresh orange juice.

If baby is very mature and seems hungry, he may be given mashed banana during this period. Ripe banana is a great food for babies because it contains amylase enzymes to digest carbohydrates.1

At Six Months

Puréed meats can be given at six months (or even earlier if baby is very mature). Meats will help ensure adequate intake of iron, zinc, and protein with the decrease in breast milk and formula.17

A variety of fruits can be introduced at this time. Avocado, melon, mangoes and papaya can be mashed and given raw. High-pectin fruits such as peaches, apricots, apples, pears, cherries and berries should be cooked to break down the pectin, which can be very irritating to the digestive tract.

As time goes by, move up in complexity with food and texture. At about six to eight months, vegetables may be introduced, one at a time so that any adverse reactions may be observed. Carrots, sweet potatoes and beets are excellent first choices. All vegetables should be cooked (steamed preferably), mashed and mixed with a liberal amount of fat, such as butter or coconut oil, to provide nutrients to aid in digestion.

Early introduction to different tastes is always a good plan to prevent finickiness. Feed your little one a touch of buttermilk, yogurt or kefir from time to time to familiarize them with the sour taste. Lacto-fermented roots, like sweet potato or taro, are another excellent food for babies to add at this time.1

At Eight Months

Baby can now consume a variety of foods including creamed vegetable soups, homemade stews and dairy foods such as cottage cheese, mild harder raw cheese, cream and custards. Hold off on grains until one year, with the possible exception of soaked and thoroughly cooked brown rice, which can be served earlier to babies who are very mature.

At One Year

Grains, nuts and seeds should be the last food given to babies. This food category has the most potential for causing digestive disturbances or allergies. Babies do not produce the needed enzymes to handle cereals, especially gluten-containing grains like wheat, before the age of one year. Even then, it is a common traditional practice to soak grains in water and a little yogurt or buttermilk for up to 24 hours. This process jump-starts the enzymatic activity in the food and begins breaking down some of the harder-to-digest components.1 The easiest grains to digest are those without gluten like brown rice. When grains are introduced, they should be soaked for at least 24 hours and cooked with plenty of water for a long time. This will make a slightly sour, very thin porridge that can be mixed with other foods.29

After one year, babies can be given nut butters made with crispy nuts (recipe in Nourishing Traditions), cooked leafy green vegetables, raw salad vegetables, citrus fruit and whole egg.

Extra Feeding Baby Tid-Bits

- How do you know when it’s time to add solids? Observe your baby’s signs. When infants are ready for solids they start leaning forward at the sight of food and opening their mouths in a preparatory way. In addition, babies should be able to sit up and coordinate breathing with swallowing. Finally, infants will stop pushing their tongue out when a spoon or bit of food is placed in their mouth–a reflex common in infants that disappears at around four months of age.30

- Keep in mind, all babies are different and will not enjoy or tolerate the same foods or textures. Experiment by offering different foods with various textures. Remember, just because your baby doesn’t like a food the first time it is introduced does not mean he will not like it the second time. Continue to offer the food, but never force.

- Baby’s food should be lightly seasoned with unrefined salt, but there is no need to add additional seasonings, such as herbs and spices in the beginning.

However by 10-12 months, your baby may enjoy a variety of natural seasonings.

However by 10-12 months, your baby may enjoy a variety of natural seasonings. - To increase variety, take a small portion of the same food you are preparing for the rest of the grown-up family (before seasoning), or leftovers, and purée it for baby (thin or thicken accordingly).

- To gradually make food lumpier, purée half of the food, roughly mash the other half and combine the two.

- Frozen finger foods are a great way to soothe a baby’s teething pain

- Keep a selection of plain yogurt, cottage cheese, eggs, fresh fruit, and fresh or frozen vegetables handy to prepare almost instant natural baby food any time–even when vacationing or traveling.

- Organic foods have minimal toxicity, thus placing a smaller chemical burden on the body. This is particularly a benefit for our youngsters. They are more vulnerable to pesticide exposure because their organs and body systems are not fully developed and, in relation to body weight, they eat and drink more than adults.

Furthermore, the presence of these chemicals in the environment leads to further contamination of our air, waterways and fields.

Furthermore, the presence of these chemicals in the environment leads to further contamination of our air, waterways and fields. - There are different ideas concerning when to offer babies water. Many resources suggest giving water about the same time solids are introduced. This is often in combination with cup drinking or sippy-cup training. Keep in mind, breast milk and formula are providing the majority of nutrients in the first 6-9 months, so it is important not to allow a baby to get too full on water. When solids become a larger part of the diet, more liquid may be needed for hydration and digestion. Also, extreme heat, dehydration, vomiting, and fever may also indicate a need for extra water. Bottom line: follow your baby’s cues. Always serve filtered water to your baby. You can add a pinch of unrefined salt to the water for minerals.

- Let baby eat with a silver spoon–the small amount of silver he will get from this really does help fight infection!

Just Say No

One important warning: do not give your child juice, which contains too much simple sugar and may ruin a child’s appetite for the more nourishing food choices. Soy foods, margarine and shortening, and commercial dairy products (especially ultra-pasteurized) should also be avoided, as well as any products that are reduced-fat or low-fat.

Soy foods, margarine and shortening, and commercial dairy products (especially ultra-pasteurized) should also be avoided, as well as any products that are reduced-fat or low-fat.

By the way, baby fat is a good thing; babies need those extra folds for all the miraculous development their bodies are experiencing. Chubby babies grow up into slim, muscular adults.

Common sense prevails when looking at foods that best nourish infant’s. A breastfeeding mother naturally produces the needed nutrition when she consumes the necessary nutrients. The composition of healthy breast milk gives us a blueprint for an infants needs from there on out. Finally, be an example. Although you won’t be able to control what goes into your child’s mouth forever, you can set the example by your own excellent food choices and vibrant health.

Egg Yolk (4 months +)

Boil an egg for three to four minutes (longer at higher altitudes), peel away the shell, discard the white and mash up yolk with a little unrefined sea salt. (The yolk should be soft and warm, not runny.) Small amounts of grated, raw organic liver (which has been frozen 14 days) may be added to the egg yolk after 6 months. Some mothers report their babies actually prefer the yolk with the liver. From Nourishing Traditions by Sally Fallon.

(The yolk should be soft and warm, not runny.) Small amounts of grated, raw organic liver (which has been frozen 14 days) may be added to the egg yolk after 6 months. Some mothers report their babies actually prefer the yolk with the liver. From Nourishing Traditions by Sally Fallon.

Pureed Meats (6 months +)

Cook meat gently in filtered water or homemade stock until completely tender, or use meat from stews, etc., that you have made for your family. Make sure the cooked meat is cold and is in no bigger than 1-2 inch chunks when you puree. Grind up the meat first until it’s almost like a clumpy powder. Then add water, formula or breast milk, or the natural cooking juices as the liquid.

Baby Pate (6 months +)

Place 1/4 pound organic chicken livers and 1/4 cup broth or filtered water in a saucepan, bring to a boil and reduce heat. Simmer for eight minutes. Pour into a blender (liver and liquid) with 1-2 teaspoons butter and a pinch of seasalt and blend to desired consistency.

Vegetable Puree (6 months +)

Use squash, sweet potatoes, parsnips, rutabagas, carrots or beets. Cut vegetables in half, scoop out seeds from squash and bake in a 400 degree oven for about an hour, or steam them (in the case of carrots and beets) for 20 to 25 minutes. Mix in butter when puréeing. You can cook these vegetables for your own dinner and purée a small portion in a blender or food mill for your baby. From Natural Baby Care by Mindy Pennybacker.

Fruit Sauce (6 months +)

Use fresh or frozen peaches, nectarines, apples, blueberries, cherries, pears, berries or a combination. Note: Whenever possible, use organic fruit, and peel the fruit if it is not organic. Cut fruit and put in a saucepan with 1 cup filtered water for every 1/2 cup of fruit. Bring to a boil; reduce to a simmer about 15 minutes or until the fruit is cooked. Purée the mixture in a blender or food mill and strain if necessary. Don’t add sugar or spices but you can stir in a little butter or cream. From Natural Baby Care by Mindy Pennybacker.

From Natural Baby Care by Mindy Pennybacker.

Dried Apricot Puree (6 months +)

Bring 2 cups filtered water to a boil with 1 pound unsulphured dried apricots and simmer for 15 minutes. Reserve any leftover liquid to use for the puree. Puree, adding the reserved liquid as necessary to achieve a smooth, thin puree. May be blended with some butter.

Fermented Sweet Potato (6 months +)

Poke a few holes in 2 pounds sweet potatoes and bake in an oven at 300 degrees for about 2 hours or until soft. Peel and mash with 1 teaspoon seasalt and 4 tablespoons whey. Place in a bowl, cover, and leave at room temperature for 24 hours. Place in an airtight container and store in the refrigerator. From Nourishing Traditions by Sally Fallon.

Baby Custard (6 months +)

Mix 1 cup raw milk or whole coconut milk, 1 cup raw cream, 6 egg yolks, 1/2 teaspoon vanilla and a pinch of stevia powder. Pour into buttered ramekin dishes. Place ramekins into a Pyrex dish filled part-way with water. Preheat oven to 310 degrees and cook for about 1 hour.

Preheat oven to 310 degrees and cook for about 1 hour.

Smoothie for Baby(8 months +)

Blend 1 cup whole yoghurt with 1/2 banana or 1/2 cup puréed fruit, 1 raw egg yolk (from an organic or pastured chicken) and a pinch of stevia.

Coconut Fish Pate (8 months +)

Place 1 cup leftover cooked fish, 1/4 teaspoon seasalt, 1/4 teaspoon fresh lime juice in a food processor and process with a few pulses. Add 1/2-1 cup coconut cream or whole coconut milk to obtain desired consistency.

Cereal Gruel for Baby (1 year +)

Mix 1/2 cup freshly ground organic flour of spelt, Kamut® , rye, barley or oats with 2 cups warm filtered water mixture plus 2 tablespoons yoghurt, kefir or buttermilk. Cover and leave at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours. Bring to a boil, stirring frequently. Add 1/4 teaspoon salt, reduce heat and simmer, stirring occasionally, about 10 minutes. Let cool slightly and serve with cream or butter and small amount of a natural sweetener, such as raw honey. From Nourishing Traditions by Sally Fallon.

From Nourishing Traditions by Sally Fallon.

Salmon and Rice Mousse (1 year +)

Heat 2 cups chicken broth to a slow boil and add 1/4 cup soaked brown rice. Lower the heat, cover tightly, and let cook for 30 minutes or until it is almost done. Wash 3 ounces salmon thoroughly and remove all bones carefully. Add the salmon to the rice, cover, and let it poach for 10 minutes or until done all the way through. Allow the salmon and rice to cool enough that it can be puréed safely in the blender or food processor. If it is too thick, add just enough water to obtain the consistency you want. Season with a little seasalt.Serve with a puréed vegetable. From The Crazy Makers by Carol Simontacchi.

Crispy Nut Butter (1 year +)

Purée equal amounts of crispy nuts, raw honey and coconut oil. Add salt to taste. Serve at room temperature. From Nourishing Traditions by Sally Fallon.

Sidebars

Foods By Age

4-6 Months

Minimal solid foods as tolerated by baby

Egg yolk–if tolerated, preferably from pastured chickens, lightly boiled and salted

Banana–mashed, for babies who are very mature and seem hungry

Cod liver oil— 1/4 teaspoon high vitamin or 1/2 teaspoon regular, given with an eye dropper

6-8 months

Organic liver–grated frozen and added to egg yolk

Pureed meats–lamb, turkey, beef, chicken, liver and fish

Butter and Cream: Added to any pureed foods

Soup broth–(chicken, beef, lamb, fish) added to pureed meats and vegetables, or offered as a drink

Fermented foods–small amounts of yoghurt, kefir, sweet potato, taro, if desired

Raw mashed fruits–banana, melon, mangoes, papaya, avocado

Cooked, pureed fruits–organic apricot, peaches, pears, apples, cherries, berries

Cooked vegetables–zucchini, squash, sweet potato, carrots, beets, with butter or coconut oil

8-12 months

Continue to add variety and increase thickness and lumpiness of the foods already given from 4-8 months

Creamed vegetable soups

Homemade stews–all ingredinets cut small or mashed

Dairy–cottage cheese, mild harder raw cheese, cream, custards

Finger foods–when baby can grab and adequately chew, such as lightly steamed veggie sticks, mild cheese, avocado chunks, pieces of banana

Cod liver oil–increase to 1/2 teaspoon high vitamin or 1 teaspooon regular dose

Over 1 Year

Grains and legumes–properly soaked and cooked

Crispy nut butters–see recipes in Nourishing Traditions

Leafy green vegetables–cooked, with butter

Raw salad vegetables–cucumbers, tomatoes, etc.

Citrus fruit–fresh, organic

Whole egg–cooked

Foods to avoid

28Up to 6 months: Certain foods, such as spinach, celery, lettuce, radishes, beets, turnips and collard greens, may contain excessive nitrate, which can be converted into nitrite (an undesirable substance) in the stomach. Leafy green vegetables are best avoided until 1 year. When cooking vegetables that may contain these substances, do not use the water they were cooked in to purée.

Up to 9 months: Citrus and tomato, which are common allergens.

Up to 1 year: Because infants do not produce strong enough stomach acid to deactivate potential botulism spores, infants should refrain from eating honey.1 Use blackstrap molasses, which is high in iron and calcium. Egg whites should also be avoided up to one year due to their high allergenic potential.

ALWAYS: Commercial dairy products (especially ultra-pasteurized), modern soy foods, margarines and shortening, fruit juices, reduced-fat or low-fat foods, extruded grains and all processed foods.

Making Homemade Baby Food

Making homemade baby food may not be as easy as opening a can, but once you have organized a cook-and-freeze routine, it is a snap. This gives you the control over food choices and cooking methods, and allows you to avoid synthetic preservatives. With careful preparation, you will maximize the nutrient and enzyme content of your baby’s food. This will make for easier digestion and better overall nutrition. One timesaving method is to cook and purée a selection of fruits, vegetables, and meats in adult quantities, and freeze them in glass custard dishes or porcelain ramekins, or just clumps on a baking sheet. These cubes can be placed in freezer bags, labeled and sealed, available for quick thawing and reheating. Thawing in the refrigerator is the most nutrient-saving method. Simply place a covered dish containing food cubes in the fridge; they will thaw in three to four hours. It only takes one to two hours at room temperature. When on the go, put the cubes in a glass container and add hot water or place the container in hot water to thaw.

Little attention is necessary to seasoning baby foods, but texture is important. Besides the basic taste, the smoothness or thickness of a food concerns baby most. To thin purées, use milk or formula. Puréed potatoes, winter squash, bananas, carrots, yogurt, nut or seed paste, and peas make great thickeners.

The only special equipment you need is a food processor, blender or a baby food mill and a simple metal collapsible steamer basket. Don’t forget the unbreakable bowls, baby spoons, and bibs. Two-handed weighted cups for drinking lessons are also a must.

How much at each meal?

With the rough outline below, one food portion is equal to approximately one tablespoon, depending on the type of ice cube or other food trays you may be using for freezing baby food. Start out slowly. Prepare a teaspoon-sized portion of whatever food you have chosen to begin with. Your baby will most likely only eat half of that small portion for the first few attempts with solids. Ultimately, baby will tell you how much he should eat. Your main concern should be making what he does eat as nutritious as possible. As your baby becomes accustomed to eating solids, you can gradually increase the portion size. Once you have ruled out sensitivities/allergies to different foods, be sure to rotate the acceptable foods in the diet–meaning, try to avoid having the same food day in and day out. The following are guidelines for 6-8 months:

Your main concern should be making what he does eat as nutritious as possible. As your baby becomes accustomed to eating solids, you can gradually increase the portion size. Once you have ruled out sensitivities/allergies to different foods, be sure to rotate the acceptable foods in the diet–meaning, try to avoid having the same food day in and day out. The following are guidelines for 6-8 months:

- Breakfast: Breast milk or formula, 1 egg yolk, 1 cube meat, 1-2 tablespoons cottage cheese or smoothie

- Lunch: Breast milk or formula, mashed banana or 1 cube fruit or vegetable

- Snack/Dinner: Breast milk or formula and 1 cube of meat, 1-2 tablespoons fermented taro or sweet potato

Portions increase for 8-10 months:

- Breakfast: Breast milk or formula, 1 egg yolk, 1-2 cubes fruit or vegetable, and 1 cube meat

- Lunch: Breast milk or formula, 1-2 cubes meat, 1-3 cubes vegetable, optional dairy such as yogurt or cheese

- Dinner: Breast milk or formula, 2 cubes meat, 1-3 cubes fruit and vegetables, yogurt or cheese

- Snacks: Finger foods or smoothie

Remember, not all babies will be eating the same amounts or foods. This portion outline is just an example. Some infants are not ready to eat 3 “meals” per day until well into the 9-10 month range. You should use the above information as a guide only and keep to your infant’s development and eating habits as well as your pediatrician’s advice.30

This portion outline is just an example. Some infants are not ready to eat 3 “meals” per day until well into the 9-10 month range. You should use the above information as a guide only and keep to your infant’s development and eating habits as well as your pediatrician’s advice.30

Not a Good Idea for Babies! (Or Their Parents or Brothers and Sisters Either!)

Almond Breeze Vanilla (Almond Milk): Purified water, evaporated cane juice, almonds, tricalcium phosphate, natural vanilla flavor and other natural flavors, sea salt, potassium citrate, carrageenan, soy lecithin, d-alpha tocopherol (natural vitamin E), vitamin A palmitate, vitamin D2

Rice Dream “Heartwise” Rice Drink Original: Filtered water, brown rice (partially milled) gum arabic, expeller pressed high oleic safflower oil, tricalcium phosphate, CorowiseTM phytosterol esters, sea salt, vitamin A palmitate, vitamin D2, vitamin B12

365 Organic Rice Milk Vanilla: Filtered water, partially milled organic rice, organic expeller pressed canola oil, tricalcium phosphate, natural vanilla flavor with other natural flavors, sea salt, carrageenan, vitamin A palmitate, vitamin D.

REFERENCES

- Fallon, Sally. Nourishing Traditions. NewTrends Publishing. 1999

- Wilson AC, Forsyth JS, Creene SA, et al. Relation of infant diet to childhood health: seven year follow up of cohort children in Dundee infant feeding study. British Medical Journal, 1998; 316:21-5.

- Scariati PD. A longitudinal analysis of infant mortality and the extent of breast-feeding in the US. Pediatrics. 1997;99:5-12.

- Pediatrics 1998;101(1):37985

- Y Takemura and others. Relaton between Breastfeeding and the Prevalence of Asthma: The Tokorozawa Childhood Asthma and Pollinosis Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. July 2001;154(2):11509

- K W Wefring and others. Nasal congestion and earache – upper respiratory tract infections in 4-year-old children. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. April 30, 2001;121(11):1329-32

- I Hardell and A C Dreifaldt. Breastfeeding duration and the risk of malignant diseases in childhood in Sweden.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. March 2001;55(3):179-85

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. March 2001;55(3):179-85 - Percival, Mark. D.C. N.D. Infant Nutrition. Health Coach System. 1995.

- Krohn, Jacqueline, M.D. Allergy Relief and Prevention. Hartly and Marks. 2000.

- Mendelsohn, Robert, M.D. How to Raise a Healthy Child in Spite of Your Doctor. Ballantine Books. 1984.

- Smith, Lendon, M.D. How to Raise a Healthy Child. M. Evans and Company. 1996.

- Thurston, Emory. Ph.D. ScD. Parents’ Guide to Nutrition for Tots to Teens. Keats Publishing. 1979.

- Jensen RG. Lipids in Human Milk. Lipids 1999;34:1243-1271

- Chen ZY, Kwan KY, Tong KK, Ratnayake WMN, Li HQ, Leung SSF. Breast Milk Fatty Acid Composition: A Comparative Study Between Hong Kong and Chongqing Chinese. Lipids 1997;32:1061-1067

- Persson, A. et al. Are weaning foods causing impaired iron and zinc status in 1-year-old Swedish infants? A cohort study. Acta Paediatr 1998; 87(6): 618-22

- Krebs, N.

Research in Progress. Beef as a first weaning food. Food and Nutrition News 1998; 70(2):5

Research in Progress. Beef as a first weaning food. Food and Nutrition News 1998; 70(2):5 - Krebs, Nancy. Dietary Zinc and Iron Sources, Physical Growth and Cognitive Development of Breastfed Infants. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:358S-360S.

- Engelmann M. D., Davidsson L., Sanstrom B., Walczyk T., Hurrell R. F., Michaelsen K. F. The influence of meat on nonheme iron absorption in infants. Pediatr. Res. 1998a;43:768-7

- Makrides, M. et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of increased dietary iron in breast-fed infants. J Pediatr 1998; 133(4): 559-62.

- Engelmann, M. et al. Meat intake and iron status in late infancy: an intervention study, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1998; 26(1): 26-33

- Jalla S., Steirn M. E., Miller L. V., Krebs N. F. Comparison of zinc absorption from beef vs iron fortified rice cereal in breastfed infants. FASEB J 1998;12:A346(abs.)

- Engelmann M. D., Sandstrom B.

, Michaelsen K. F. Meat intake and iron status in late infancy: an intervention study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1998b;26:26-33

, Michaelsen K. F. Meat intake and iron status in late infancy: an intervention study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1998b;26:26-33 - Westcott J. L., Simon N. B., Krebs N. F. Growth, zinc and iron status, and development of exclusively breastfed infants fed meat vs cereal as a first weaning food. FASEB J 1998;12:A847(abs.)

- Birch L. L., Grimm-Thomas K. Food acceptance patterns: children learn what they like. Pediatr. Basics 1996;75:2-6

- Sears, William, M.D. Sears, Martha, R.N. The Baby Book. Little, Brown, and Company. 1993.

- Nutritional effect of including egg yolk in the weaning diet of breast-fed and formula-fed infants: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 75, No. 6, 1084-1092, June 2002

- Enig, Mary. Ph.D. Dietary Recommendations for Children – A Recipe for Future Heart Disease? Accessed August 17, 2004.

- Pennybacker, Mindy and Ikramuddin, Aisha. Natural Baby Care.

Mothers and Others for a Livable Planet. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 1999.

Mothers and Others for a Livable Planet. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 1999. - Cowan, Tom M.D. Feeding Our Children. Found at www.fourfoldhealing.com on January 12, 2005.

- Information found at www.wholesomebabyfood.com on December 29, 2004.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly magazine of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Summer 2005.

🖨️ Print post

Read this in: ČeštinaDeutsch

Bringing Up Baby: When to Wean … and How

Read this in: Español

🖨️ Print post

Debate on how to feed a growing baby permeates the Internet. When should moms introduce solid food? And what kinds of foods should come first? What about baby-led weaning—is that the way to go? Does it even matter what baby eats?

In these online debates, many moms agree with the statement that “food before one is just for fun.” But the practices of non-industrialized peoples, supported by modern science, show us that the early months are the most important time of life for the right kind of diet—a nutrient-dense diet that will determine babies’ growth and development during the early years and overall health for the rest of their lives.

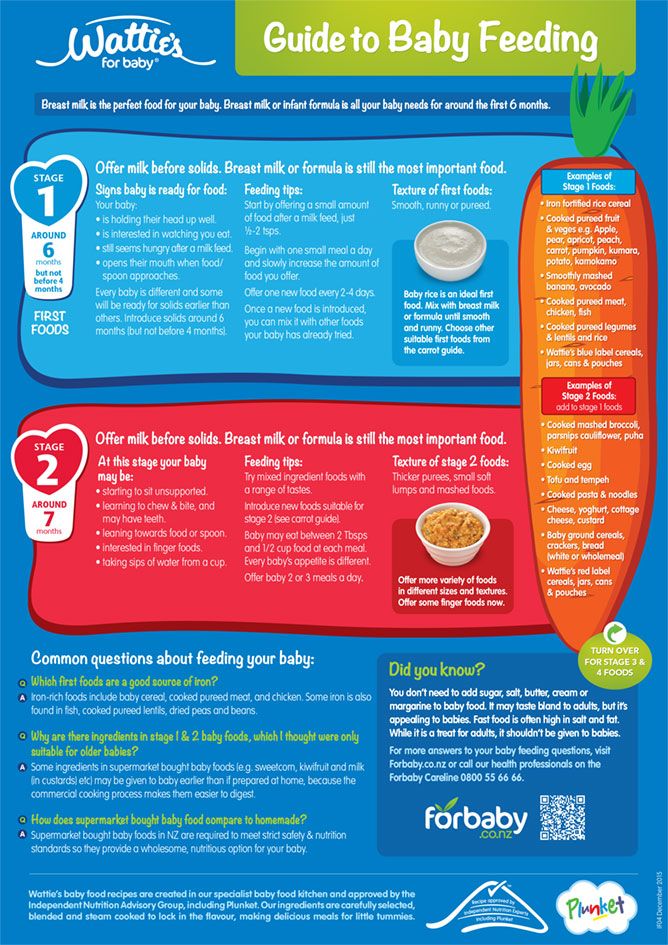

WHEN TO WEAN?

Internet discussions on infant feeding start with debate on the best time to introduce solid foods. Most medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the World Health Organization and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition recommend the introduction of solid foods sometime between the fourth and sixth months. All are in agreement that solid foods before the fourth month can predispose babies to gastrointestinal problems and allergies; at the same time, these organizations note that delaying introduction of solid foods after six months may result in baby not getting all the nutrients needed.

These recommendations about when to begin solid foods are completely in accord with those of the Weston A. Price Foundation.

Very mature—or fast-growing—babies will be ready for some solid food at four months, while smaller, less mature babies may not be ready until six months. Moms often find that with the introduction of pureed foods, their baby becomes less fussy, goes longer between feedings and sleeps better through the night—a great relief to mom herself as she can also sleep through the night and settle into a better routine. Of course, moms can and should continue nursing or using the raw milk formula for as long as they like. Some babies enjoy nursing for up to three or four years; others lose interest before they are a year old.

Moms often find that with the introduction of pureed foods, their baby becomes less fussy, goes longer between feedings and sleeps better through the night—a great relief to mom herself as she can also sleep through the night and settle into a better routine. Of course, moms can and should continue nursing or using the raw milk formula for as long as they like. Some babies enjoy nursing for up to three or four years; others lose interest before they are a year old.

In online debates, many mothers object to giving any solid food before six months, and some argue that solid foods should be delayed as long as possible—in other words, making the case for prolonged exclusive breastfeeding. Some claim that baby can get everything needed from breastmilk alone even past the one-year mark; one mother, recognizing the research showing that babies need more iron than mom can supply after six months, and that the mineral levels in mom’s breastmilk decline over time, suggests solving the problem by letting baby get his minerals by playing in the dirt! Others cite their babies’ “lack of interest in food,” often describing how little food gets into baby’s mouth when they practice baby-led weaning (more on this later).

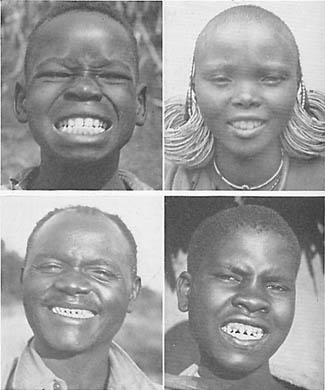

In questions of this importance, our first step is to look at the practices of traditional peoples—and then to see whether they jibe with what modern science has to tell us. On this topic, we have two studies that provide us with valuable information. One is a 1983 survey of childbirth and breastfeeding practices in one hundred eighty-six non-industrialized cultures.1 The main focus of the study was maternal bonding traditions, but the authors also looked at feeding practices. They were surprised to find that most cultures began weaning at six months or earlier. In fact, in one-third of the cultures, solid foods were given before one month of age!

Contrary to the expectation of a prolonged period of breast-milk as the sole source of infant nutrition, solid foods were introduced before one month of age in one-third of the cultures, at between one and six months in another third, and was postponed more than six months for only one-third.1

A more recent survey from 2001 looked at infant feeding practices in one hundred thirteen non-industrialized populations from around the world. 2 The researchers found that more than half the cultures introduced solid foods before six months, with five to six months being the most common timeframe. Breastfeeding continued for anywhere from ten to twenty-nine months.

2 The researchers found that more than half the cultures introduced solid foods before six months, with five to six months being the most common timeframe. Breastfeeding continued for anywhere from ten to twenty-nine months.

Some online comments indicate that WAPF’s advocacy of solid foods by six months is proof of our “opposition” to breastfeeding. Nothing could be further from the truth—the solid foods are in addition to breastmilk (or homemade formula when necessary). The combination of solid foods plus breastmilk can continue for many months.

By the way, this is exactly what we see in the animal world. Baby animals breastfeed exclusively only for a short period of time—just a month or so in the case of cows and pigs—and then get nourished with a combination of solid foods plus breastmilk for a much longer period.

The key reason for the introduction of solid food by six months is the baby’s iron status. Although a mother’s breastmilk contains lactoferrin, which helps the baby absorb 100 percent of the iron in her milk, iron content is generally low. One explanation for this is that babies need more zinc than iron during the first few months of life, and breastmilk is high in zinc. Babies should also get a good supply of iron in the cord blood, but the normal turnover for red blood cells is four months. By six months, iron deficiency is a distinct possibility in the exclusively breastfed baby. In fact, mineral levels start to decline in mother’s breastmilk almost from birth and continue to fall after the six-month mark. A 1984 study showed a decrease in zinc, copper and potassium.3 And a 1990 study of mothers in Bangladesh documented a decline in zinc and copper over time.4

One explanation for this is that babies need more zinc than iron during the first few months of life, and breastmilk is high in zinc. Babies should also get a good supply of iron in the cord blood, but the normal turnover for red blood cells is four months. By six months, iron deficiency is a distinct possibility in the exclusively breastfed baby. In fact, mineral levels start to decline in mother’s breastmilk almost from birth and continue to fall after the six-month mark. A 1984 study showed a decrease in zinc, copper and potassium.3 And a 1990 study of mothers in Bangladesh documented a decline in zinc and copper over time.4

What about the argument that allergies can be avoided by delaying solid food? A recent review of available research found that where the risk of allergy is a key consideration, introducing solids at four to six months may result in the lowest allergy risk.5 Said the authors of the review, “When all aspects of health are taken into account, the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding and age of introduction of solids were confirmed to be six months, but no later. ”

”

Another argument holds that baby’s gut is too permeable for solid food at four months, or even much later. We asked Natasha Campbell- McBride for her opinion on this—remember that she is one of the world’s experts on gut permeability. Her reply: “The majority of babies are ready to be weaned by six months, but many babies are ready earlier—they start getting hungry because they don’t get enough from the mother’s milk. To add formula to those babies is not a good idea; it is much better to start adding real foods [although] no grains, beans or any other starchy and difficult-to-digest plant foods. Animal foods—meat stock, meats, fish, eggs and fermented raw dairy (from proper milk)—should be introduced, as well as cooked vegetables and some freshly pressed juices from raw vegetables and fruit. Gradually! The gut wall of babies is permeable for a reason, because it is necessary to develop oral tolerance of a plethora of antigens from the environment. Introducing foods during that time ensures that the child develops tolerance and can eat natural foods without reacting with allergies. ” (I’m not sure we agree about the juices, but in everything else, Dr. Campbell-McBride and WAPF are in accord.)

” (I’m not sure we agree about the juices, but in everything else, Dr. Campbell-McBride and WAPF are in accord.)

Back to the assertion that “food before one is just for fun.” There is no age at which baby is growing faster—and forming more connections in the brain—than the age from zero to one. This is not the time to be casual about feeding your baby—because food before one matters a ton! The way you feed baby—when and what and how—will make all the difference in his or her future health, appearance and intelligence.

BAD ADVICE

It’s very clear from both tradition and science that babies should receive solid foods by age six months—advice with which WAPF is in complete agreement. As for what to feed baby, here we are mostly in disagreement with conventional recommendations.

In fact, what passes for advice on infant feeding in books and on the Internet is not only confusing and conflicting, but woefully inadequate. Most health professionals are absolutely clueless when it comes to nourishing a baby during that critical first year of life.

Let’s start with the AAP—we might assume that this august institution would have the most accurate and detailed advice on how to feed baby. Here’s what they recommend: introduce solid foods around six months of age; expose baby to a wide variety of healthy foods; and offer a variety of textures.6 These suggestions don’t seem very helpful, to put it mildly.

BABY FOOD IN PLASTIC CONTAINERS

Get your child used to phthalates at an early age!

An older AAP suggestion, which persisted for many years, was to give iron-fortified rice cereal as baby’s first food. Widespread criticism about starting baby off on pure carbs and the recent arsenic scandal (which found high levels of arsenic in conventional rice) have the AAP retreating from this dogma. Today, if you dig around on the AAP website long enough, you will find a grudging recommendation for red meat as a source of iron for baby.7

By the way, years ago, the AAP refused to recommend soy infant formula, due to reports of severe intestinal damage and thyroid problems in babies fed this toxic food. But when the AAP built its shiny new headquarters, the organization accepted a large contribution from the formula industry; the AAP’s objections to soy formula then disappeared.

But when the AAP built its shiny new headquarters, the organization accepted a large contribution from the formula industry; the AAP’s objections to soy formula then disappeared.

However, most moms don’t query the AAP when they decide to feed solid food to their babies; they just go to the grocery store. There they will find mostly pureed fruits and vegetables, along with strange mixtures like quinoa and peas. Plain pureed meat will come with a “gravy” of water and cornstarch. In the old days, you could purchase pureed liver or egg yolk for your baby, but no longer.

Even worse, conscientious mothers are unlikely to find many choices in glass jars. Instead, much baby food today comes in plastic (so you can introduce phthalates at an early age) or aseptic containers lined with aluminum and flash heated to 295°F. And yes, aluminum does migrate into the food when heated to such high temperatures, especially for acidic foods like applesauce.

What about the USDA dietary guidelines? Can they enlighten us? The book MyPlate for Moms: How to Feed Yourself & Your Family Better8 provides the following recommendations for feeding infants:

Lean meat or tofu

Occasional egg

Occasional cheese

Fruits and vegetables

Whole grains – dry breakfast cereals

Lowfat milk

Low-trans spreads

Reduced salt

This is a largely plant-based diet, with most calories coming from fruits and vegetables. Baby is allowed no butter or other animal fats, and there is no suggestion of organ meats. He will get small amounts of fat from the lean meat and occasional egg and cheese, but if mom decides to feed tofu rather than meat, even these sources of fat will be lacking.

Baby is allowed no butter or other animal fats, and there is no suggestion of organ meats. He will get small amounts of fat from the lean meat and occasional egg and cheese, but if mom decides to feed tofu rather than meat, even these sources of fat will be lacking.

Recently the Weston A. Price Foundation was asked to endorse the book, What to Feed Your Baby,9 by Tanya Altmann, MD, FAAC, a pediatrician who claims to be a spokesperson for the AAP. “Dr. Tanya Altmann knows that good nutrition is essential for healthy kids,” reads the back-of-book copy: “In What to Feed Your Baby, Dr. Tanya provides the latest nutritional recommendations and best practices for feeding babies and young children.”

The “latest nutritional recommendations” suggest eleven foundational foods for your baby:

Eggs

Prunes

Avocadoes

Fish

Yogurt/cheese/milk

(soy milk if allergic to cow’s milk)

Nuts

Chicken/beans

Fruit

Green veggies

Whole grains

Water

Dr. Altmann also advises parents to avoid giving salt to their babies, and there is no butter or other animal fats, no red meat and no organ meats on this list. Baby gets lowfat or nonfat milk after age two, but plenty of rough whole grains—which could include rice cakes, “multi-grain” Cheerios and even granola—foods impossible for baby to digest. Needless to say, we did not endorse her book!

Altmann also advises parents to avoid giving salt to their babies, and there is no butter or other animal fats, no red meat and no organ meats on this list. Baby gets lowfat or nonfat milk after age two, but plenty of rough whole grains—which could include rice cakes, “multi-grain” Cheerios and even granola—foods impossible for baby to digest. Needless to say, we did not endorse her book!

Modern suggestions for babies: a plant-based diet.

Overall, it seems that fruits and vegetables have replaced rice cereal as baby’s first foods, as illustrated in the meme below—but pasta and toasted (why toasted?) bread are OK. These guidelines allow small amounts of animal foods but state that it’s no problem to replace these with tofu. In all versions of conventional guidelines, Dr. Altmann’s included, and in baby foods sold at the grocery store, animal fats are absent, and no one seems to understand the concept of nutrient density for baby.

BABY-LED WEANING?

Recently I visited a Whole Foods in Washington, DC, and went upstairs to the café area to eat my lunch (cheese and homemade paté) before shopping. A woman with a baby of about eight months sat at the table next to mine. She ate a meal she had purchased at the deli. But what did baby in her high chair get? A few pieces of green pepper and cucumber on the high chair tray. When they left, those vegetable slices were scattered on the floor, with no evidence that baby had eaten much of anything.

A woman with a baby of about eight months sat at the table next to mine. She ate a meal she had purchased at the deli. But what did baby in her high chair get? A few pieces of green pepper and cucumber on the high chair tray. When they left, those vegetable slices were scattered on the floor, with no evidence that baby had eaten much of anything.

It’s likely this mom was following the suggestions of Baby-Led Weaning,10 a best-selling book on how to feed babies. Marketing for the book characterizes the approach as “The Natural, No-Fuss, No-Purée Method for Starting Your Baby on Solid Foods.” As described on Amazon, “Baby-Led Weaning explodes the myth that babies need to be spoon-fed and shows why self-feeding from the start of the weaning process is the healthiest way for your child to develop. With baby-led weaning (BLW, for short), you can skip purées and make the transition to solid food by following your baby’s cues.”

Typical meal for baby—you’d look sad too, if you had to eat this way. Baby gets zero nourishment from lettuce.Expect a mess!

Baby gets zero nourishment from lettuce.Expect a mess!The premise of baby-led weaning is that mom doesn’t need to spend any time in the kitchen making purées for her six-month-old child, but that baby can be fully nourished on chunks of food like broccoli and rice cakes. The idea is to put “a variety of foods in front of baby and baby will know what to eat.” Furthermore, according to the authors, babies need this training in order to learn to put things in their mouths without any spoon feeding. (Seriously!) Babies need to eat with the family at the table, and baby-led weaning is the way to accomplish this. Also, babies might be traumatized and grow up to be axe murderers if you put a spoon in their mouths and feed them yourself. Please forgive my sarcasm, but as a mother of four children who grew up just fine after their infant diet of purees, I have to wonder where this deep-seated aversion to pureed baby food and initial spoon-feeding is coming from.

According to Baby-Led Weaning, baby’s early diet should look something like the pictures below.

One has to ask; how much nourishment is baby getting from carrot sticks and pieces of lettuce? How much is even going down the gullet? And what about the danger of choking?

There is just so much wrong with this book. . . . Let’s start with the dietary guidelines themselves. Suggestions for baby’s first foods include raw carrot, raw broccoli and a strip of meat—remember, baby doesn’t have molars yet! Even adults sometimes have trouble chewing a strip of meat. Baby gets full-fat dairy but no butter. Instead, he gets “healthy fats” such as vegetable oils, oily fish and olive oil. Salt is bad for babies, insist the authors of Baby-Led Weaning. Baby gets whole grains, including oat cakes, rice cakes and dry breakfast cereal (Rice Crispies are especially recommended). According to the authors, pasta and pizza are OK—they make great finger foods, after all! And microwaving is also OK. The key is that mom just puts a few of these objects on baby’s tray, and baby then “tells” mom what he is going to eat. Once baby learns to talk, he can even dictate all his food choices! Don’t be surprised if he wants to eat nothing but pizza.

Once baby learns to talk, he can even dictate all his food choices! Don’t be surprised if he wants to eat nothing but pizza.

As justification, proponents of baby-led weaning point to a 1926 baby feeding study by Clara Davis, carried out at the Mt. Sinai Hospital in Cleveland. In this study, Davis fed a group of orphans by putting a variety of foods in front of them every day.11,12

The first thing to notice is the choice of foods that Davis considered important for babies. These included “sweet milk”—in 1926, that would be whole raw milk—as well as sour milk. In addition to fruits, vegetables and grains, the babies got to choose from beef, lamb, chicken, bone marrow, bone jelly, sweetbreads, brains, liver, kidneys, fish and eggs. Notice all the organ meats and the lamb jelly! To top it off, babies got to dip their fingers in a bowl of sea salt! Most importantly, Davis did not give the infants any foods containing sugar and white flour.

The babies did well—they thrived and had rosy cheeks. Does that mean the babies knew what they should eat? No, it means that Clara Davis knew what babies should eat—far, far better than what modern moms know, plunking slices of green pepper down on the high chair tray.

Does that mean the babies knew what they should eat? No, it means that Clara Davis knew what babies should eat—far, far better than what modern moms know, plunking slices of green pepper down on the high chair tray.

Commentators have declared that the Davis study shows that “all the babies ended up eating a balanced diet.” The babies did well, for sure, but how do we know they all got a balanced diet? Did they measure the nutrient levels in the foods? Were the babies followed into adulthood? Were they given blood tests to determine blood levels of vitamins and minerals?

The babies studied by Davis developed definite tastes. For example, one baby ate two pounds of oranges in one day. I’m not sure I would call that a “balanced diet.” If I had a child who only wanted to eat oranges, I would not let him tell me what he wanted to eat, but do my best to vector him to other foods.

But the key point is this: In the Davis study, the foods were mashed, ground up or finely minced—not raw and in big chunks. Moreover, when the babies indicated what they wanted, the nurses fed them with a spoon. Babies also ate with their fingers. The baby-led weaning folks have definitely twisted the Davis study to justify giving babies raw broccoli or raw carrots as their first foods!

Moreover, when the babies indicated what they wanted, the nurses fed them with a spoon. Babies also ate with their fingers. The baby-led weaning folks have definitely twisted the Davis study to justify giving babies raw broccoli or raw carrots as their first foods!

Another flaw: The cover of Baby-Led Weaning promises “no purees, no stress, no fuss.” But moms are advised to “expect a mess.”

Motherhood is hard enough without having to clean up a mess like this, three to four times per day! Making purees for your baby is a joyful, relaxing activity—but cleaning up a horrendous mess at every feeding time is stressful indeed!

PARENT-LED FEEDING

It’s easy to feed purees to baby, even before he can sit up. Put a bib on and strap him into a child seat. (Later you can feed him in a high chair.) The puree should be thin and easy to swallow—the food can get thicker as baby gets older, but the first purees should be somewhat watery.

At first, baby will push a little food out with his tongue (called tongue thrust). Actually, at the first feeding, he will push most of it out. Just be patient and keep putting it back in his mouth, and he will soon get the hang of it. (You can also let baby lick the food off your fingers for the first few tries.) Baby pushing food out does not mean that “baby is not ready for solid foods” or “baby is not hungry,” as some mothers say. It just means that baby is still learning how to eat.

Actually, at the first feeding, he will push most of it out. Just be patient and keep putting it back in his mouth, and he will soon get the hang of it. (You can also let baby lick the food off your fingers for the first few tries.) Baby pushing food out does not mean that “baby is not ready for solid foods” or “baby is not hungry,” as some mothers say. It just means that baby is still learning how to eat.

While feeding him, you can talk to him and laugh. Baby will not be traumatized. At first, he may seem surprised, but soon he will coo and kick his legs with delight. Rather than leave a child alone with some food objects on his tray, you can make meals a time of real engagement with baby. You are looking at him; talking with him; laughing with him. This is the right kind of training for family meals—the association of food with pleasant social interaction. And finally, there is no mess! No yucky food on high chair, floor and baby for mom to clean up.

What about family meals—do we need to practice baby-led weaning to have baby participate in family meals? Not at all! In fact, a lot of family members would not find it enjoyable to eat with a baby making a terrible mess with his food.

Instead, feed baby his puree before the family meal, so that he is well-fed, satisfied and not fussy. Then at meal time, put a few small pieces of banana or cheese on his tray—something nourishing but not too messy. Let him play with those while the rest of the family eats. If he is teething, give him a bone to chew on—bones are a great teething tool, but definitely not a source of nourishment at that age. As he grows older, you can start giving him some of the family food, such as soup or finely minced stews, fed to him with a spoon until he learns how to do this himself.

There are so many downsides of baby-led weaning. Let me count the ways: malnutrition, wastefulness, choking risks, messiness, and horrible family meals—but the most serious may be that this feeding approach pretends to put baby in charge of what he eats.

Mom and Dad need to be in charge of what baby eats. Baby does not know what to eat; only wise parents know what and how to feed baby. Gladys Davis herself concluded that food selection for young children should be left “in the hands of their elders where everyone has always known it belongs.”

Gladys Davis herself concluded that food selection for young children should be left “in the hands of their elders where everyone has always known it belongs.”

If you put a cookie on baby’s high chair tray, he will eat it even though this is a horrible choice for a baby. Of course, if baby exhibits a real aversion to something you are feeding her (demonstrated, for example, by throwing up), then you will need to find a substitute (but equally nutritious) food.

The precedent of parents deciding what baby should eat needs to be established from the start. Give baby plenty of freedom to play, develop and explore on his own, but take full charge of baby’s diet—his good health and optimal development depend on it.

WHAT TO EAT?

At no other time in his life will your baby be growing as fast or making as many brain cells as during the first year of life—and this growth and development cry out for abundant nourishment.

During the first year of life, your baby is programmed to make seven hundred new neural connections every second, and the cerebellum triples in size, corresponding to the rapid development of motor skills that occurs during this period. Full vision comes online in the first year, and language circuits in the frontal and temporal lobes become consolidated.

Full vision comes online in the first year, and language circuits in the frontal and temporal lobes become consolidated.

During the toddler years, the number of nerve connections in the brain increases to one thousand trillion, twice the number the baby had at birth. Myelin, an insulating material around these nerves, is diminished in malnourished toddlers because fewer cells that make myelin are produced. This can result in smaller brains. What does baby need to produce myelin? First and foremost, cholesterol! There’s no cholesterol in rice cereal or vegetables—and baby cannot make his own cholesterol at this young age. He must get it from the diet.

Your baby also needs abundant choline—another nutrient absent in typical baby foods. Baby goes through windows of opportunity when brain connections can be made—and without choline, these connections won’t occur. Consuming choline later will not help—it needs to be there and available for making the connections during the specific windows of opportunity.

Iron deficiency in one- to two-year-olds has been linked to learning and behavior problems, including irreversible cognitive problems. Fat is also crucial for toddlers because it’s needed for the accelerated pace of myelin formation during this period. Fats carry the fat-soluble vitamins A, D and K2, which are critical for neurological development. Your baby cannot absorb iron without vitamin A. Thus for optimum brain development, at least 50 percent of a child’s total calories should come from fat, mostly animal fat.

Bone density is established during the first year of life. As bones are forming and growing, baby needs easily absorbed calcium and phosphorus, plus vitamin D, vitamin A and vitamin K2—along with numerous other cofactors.

B12 is critical to all these processes—there’s no vitamin B12 in plant foods. And abundant B6 is also important, largely supplied by animal foods.

Given these nutritional requirements, which foods from Table 1 (next page) would you choose for your baby’s first foods? It’s obvious that baby’s first foods should be liver and egg yolk—not only for the abundant cholesterol and choline they provide, but also for minerals, fat-soluble vitamins and vitamins B12 and B6. For variety, red meat and gizzards are also good, but nothing can match egg yolks and chicken liver for nutrient density. Start feeding these at four to six months, depending on the maturity of the baby. Natural cod liver oil, for vitamins A and D, can be given even earlier, starting at three months. It’s easy to give cod liver oil using a syringe or eye dropper.

For variety, red meat and gizzards are also good, but nothing can match egg yolks and chicken liver for nutrient density. Start feeding these at four to six months, depending on the maturity of the baby. Natural cod liver oil, for vitamins A and D, can be given even earlier, starting at three months. It’s easy to give cod liver oil using a syringe or eye dropper.

None of the foods listed above is a significant source of calcium, but remember that baby should still be breastfeeding or getting a raw milk formula. Raw milk (human or otherwise) provides calcium, phosphorus and many minerals in abundance (the exception being iron), plus a myriad of compounds that build the immune system, strengthen the gut wall and protect against pathogens. And raw milk is an important source of vitamin C for your child.

For the egg yolk, boil a whole egg—preferably pasture-raised—for three and one-half minutes; then peel and discard the white. Add a pinch of salt to the yolk (which will still be soft). Start by feeding just one-half teaspoon on a spoon (or have baby lick the egg yolk off your finger) and gradually build up from there. An even easier way is to dip your finger in the runny egg yolk of your own fried egg and let baby lick it off; then graduate to giving it to him with a spoon. If baby does not adjust to the egg yolk or has an allergic reaction, hold off for a week or two and then try again. Some moms have found that babies don’t tolerate egg yolk on its own, but do fine with egg yolk mixed with liver puree.

Start by feeding just one-half teaspoon on a spoon (or have baby lick the egg yolk off your finger) and gradually build up from there. An even easier way is to dip your finger in the runny egg yolk of your own fried egg and let baby lick it off; then graduate to giving it to him with a spoon. If baby does not adjust to the egg yolk or has an allergic reaction, hold off for a week or two and then try again. Some moms have found that babies don’t tolerate egg yolk on its own, but do fine with egg yolk mixed with liver puree.

Baby’s first pureed liver should be very runny—and have salt added. You can also stir in a little butter or cream. Once baby has adjusted to his egg yolk and liver, you can add other foods, such as pureed red meat, pureed fish, pureed dark chicken meat, and pureed fruit and vegetables with cream or butter. Puree meats with water, bone broth, raw milk or cream, and always with added fat, especially butter. Introduce new foods one at a time and observe any possible allergic reactions.

As he or she matures, baby can also be given finger foods cut into small pieces, such as banana and cheese. Salmon eggs make a great finger food, as do dried anchovies. For a real treat, give baby bits of natural bacon!

Another critical food for baby is salt. Salt provides chlorine for hydrochloric acid production—without salt it will be difficult for your baby to digest the meats you are giving him. And the sodium in salt is essential for brain development. Formula makers learned this lesson the hard way when they produced a low-chloride, low-sodium baby formula called Neo-Mul-Soy. The babies on this formula had very retarded intellectual development (compared to babies on regular soy formula) and, after several lawsuits, the formula was removed from the market. Yet very few baby foods contain salt, and almost all books on feeding babies claim that babies should not consume salt. For shame! Be sure to put salt in all your baby’s purees and egg yolk, and also consume plenty of salt while you are breastfeeding—and make that unrefined salt to provide adequate magnesium and trace minerals.

As for fruits and vegetables, in the early days these should be well cooked, then pureed or mashed, and mixed with butter or cream. Raw fruit contains pectin, which is very hard on the immature digestive tract. The exception is ripe bananas, which are a fine early baby food and a good source of vitamin B6. Mash a few banana slices with a little cream and a pinch of salt—your baby will love this!

As for hard-to-digest foods like grains, egg whites and raw fruits and vegetables, it’s best to wait until baby is at least one year old for these. Again, introduce slowly and watch for any allergic reactions. Introduce whole egg as scrambled egg, made with extra yolks and cream. Grains should be soaked overnight in an acidic medium (water with a small amount of lemon juice, vinegar, yogurt, kefir or whey) and then well cooked. A toddler can eat bread if it is genuine sourdough bread—spread thickly with butter, of course.

Remember that above all, babies need animal fats. They are critical for growth, hormone production and indeed practically all functions in the body, right down to the mitochondria. Animal fats provide cholesterol for neurological development; arachidonic acid for healthy skin, brains and digestion; and fat-soluble vitamins needed for just about everything, including iron assimilation and hormone production.

They are critical for growth, hormone production and indeed practically all functions in the body, right down to the mitochondria. Animal fats provide cholesterol for neurological development; arachidonic acid for healthy skin, brains and digestion; and fat-soluble vitamins needed for just about everything, including iron assimilation and hormone production.

Above all, remember that you are in control, especially during that critical first year. In fact, this is the only time in baby’s life that you will have complete control over what baby eats. It’s the time when habits and tastes are created, and the path for optimal growth and development is set. As baby grows into a child and then an adult, you will not have that control, but the good start you give your baby in those early years—especially during the first year—will protect him against the inevitable indulging in processed food that will occur as he makes his way in the wider world.

SIDEBARS

SUPPLEMENTS FOR BABY

Should babies receive supplements? The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) says yes, recommending that baby get added iron and vitamin D in tacit recognition that the infant diet the AAP promotes lacks these nutrients.

However, supplemental iron for baby should be avoided at all costs. The inorganic iron in supplements can increase susceptibility to infectious diseases as well as encourage inflammatory chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, liver disease and even cancer.13 Of course, babies do need iron but only from iron-rich foods that contain important cofactors (copper and vitamin A), such as liver and egg yolk.

Likewise, vitamin D supplements can cause calcium build-up in the soft tissues, where it does not belong. Baby needs vitamin D from foods like cod liver oil, butter and egg yolks, which also supply vitamin A.

Beware children’s chewable vitamin tablets, which contain refined sweeteners like sugar, fructose, maltodextrin and sorbitol, along with colorings, flavorings and fillers. The “vitamins” they contain are all synthetic and unlikely to do your baby any good. Instead, baby will be beautifully nourished with real, nutrient-dense foods like liver, egg yolks, butter, cod liver oil, unrefined salt, raw dairy products and pastured meats; with these in his diet, he won’t lack for any of the essential nutrients.

ANOTHER REASON TO MAKE YOUR OWN

In February, a congressional subcommittee report made headlines when it disclosed that 95 percent of tested baby foods contained toxic, IQ-lowering heavy metals. According to the report, titled “Baby Foods Are Tainted with Dangerous Levels of Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium, and Mercury,” both conventional and organic baby foods display high levels of the metals. None of the products come with warning labels for parents. The report’s authors noted the disturbing implications: “Exposure to toxic heavy metals causes permanent decreases in IQ, diminished future economic productivity, and increased risk of future criminal and antisocial behavior in children” and “endangers infant neurological development and long-term brain function.”

Four companies—Nurture (HappyBABY brand), Beech-Nut, Hain (Earth’s Best Organic) and Gerber—cooperated with the subcommittee’s request for internal documents and test results. Arsenic, lead and cadmium were detected in baby foods made by all four responding companies, and high levels of mercury were found in products made by Nurture—the only company even to test for mercury. For all four metals, the results were “multiples higher than allowed under existing regulations for other products.” Three companies—Campbell (Plum Organics), Walmart (Parent’s Choice) and Sprout Organic Foods—refused to cooperate. The report’s authors speculate that the three companies’ “lack of cooperation might obscure the presence of even higher levels of toxic heavy metals in their baby food products, compared to their competitors’ products.”

For all four metals, the results were “multiples higher than allowed under existing regulations for other products.” Three companies—Campbell (Plum Organics), Walmart (Parent’s Choice) and Sprout Organic Foods—refused to cooperate. The report’s authors speculate that the three companies’ “lack of cooperation might obscure the presence of even higher levels of toxic heavy metals in their baby food products, compared to their competitors’ products.”

Source: Subcommittee on Economic and Consumer Policy. Baby Foods Are Tainted with Dangerous Levels of Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium, and Mercury. Committee on Oversight and Reform, U.S. House of Representatives, February 4, 2021.

REFERENCES

- Lozoff B. Birth and ‘bonding’ in non-industrial societies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1983;25(5):595-600.